Introduction

The substance use disorders are among the most complex mental diseases due to disturbances generated in the homeostasis of the body, in addition to compromising the different dimensions of the subject: labor, social, cognitive, emotional, among others;1 abuse or dependence of these substances generates disabilities in patients and attendants, which can deteriorate the patients quality of life and even lead to death,2,3 Despite the many teaching and education campaigns, consumption of both legal and illegal substances has been maintained, and even has become a documented comorbidity in other mental illnesses, often in patients infected with HIV virus and teens.3-5

In a study conducted in Latin America in 2011 by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, which included the collaboration of 7 countries, the prevalence of psychoactive substances in patients attending emergency rooms at the institutions included in the study were evaluated. Among the results obtained it was found that the most consumed substance was tobacco, followed by alcohol and marijuana, which were common findings in all the countries participating.6-8

The management of patients with substance abuse or dependence is aimed at helping the patient to abandon the drugs seeking and compulsive use; however, the treatment of these diseases tend to be long and includes bad adhesions, partly because patients who choose to undergo treatment are chronic users and in many cases have experienced failures in previous treatments. The duration of treatment in patients with such diseases reported relapse rates of up to 40 or 50%, so the treatment must be made on more than one occasion.9

There are different ways to handle substance abuse, among which are the use of therapeutic communities (TCs), which are defined as self-help programs for abandonment of harmful substance use behaviors and health recovery the patient via an individual personal growth, which is performed based on separating the subject from society submitting it to a residential program in a specific community with a qualified professional staff and other patients suffering from the same diseases or substance abuse problems.10,11

Trying to establish the standards by which must abide the TCs, authors such as De Leon established a number of criteria that must be present in each of these institutions, in order to ensure better quality in the services provided to patients. These criteria include a therapeutic plan, activities undertaken and even the communities' staff organization.

Due to the worldwide TCs boom, there have been various models of these; however, not all have all the quality standards suggested by the World Federation of Therapeutic Communities, which could result in that not all programs have the same success and relapses rates.12 These has questioned the effectiveness of the TCs, however, via systematic reviews and meta analyzes, it was found that more studies are needed, however there is evidence to conclude that there is benefit on this therapy for the treatment of persons addicted to psychoactive substances. At the same time they emphasize that it is not possible to tell whether there is a better model, due to the paucity of studies used to compare them.12-14) So, it is necessary to evaluate the presence and availability of TCs worldwide, in order to assess the quality of them, and design policies and recommendations improving existing TCs, besides presenting this treatment method in a more uniform and organized way to patients and their families. First, a multicenter study that allows to describe quantitatively and qualitatively TCs available in 5 Latin American countries is made, and for which we had the support of the Latin American Federation of Therapeutic Communities (FLACT), TCs regulator in the region.

Methods

A multicenter descriptive study of quantitative characteristics, including 5 countries in Latin American, was performed. These countries were Brazil (Provincia de Sao Pablo), Mexico (Provincia de Jalisco), Argentina, Peru and Colombia. Through the FLACT or the competent entity in each country, we contacted the respective national organizations responsible for the TCs regulation in order to identify the TCs registered for 2012. Once identified, we tried to contact them through different media for inviting them to participate in the study, with a timeout response of 7-8 weeks.

If we had success, an email or an envelope containing the questionnaire (adapted to each country), cover letters from the main investigator, the FLCAT president, the TCs president at a national associated level was sent; or a phone call from the local study coordinators of each country was made.

The questionnaire sent to each of TCs included a module evaluating compliance with the criteria established by De Leon10 (Table 1), reviewing the quality of the institution and assigning a score of 1 if the community fulfilled the criteria and 0 if not, with a maximum added score of 12 points. In addition, questionnaires about patient flow, facility infrastructure, health services provided, the reasons why the patients leave the treatment, and the main diseases treated were sent. This was a self-evaluation process that was answered and returned by each of the director of the participant communities. Like any self-evaluation process, there were some biases such as the alteration of self-perception, either in a positive or negative way.

Once the answers from each of the TCs were obtained, this data was collected on a Microsoft Excel document, with the subsequent calculation of rates and proportions, and finally we generate the respective charts and organized summaries.

Results

Therapeutic communities identified and participation in the study

A total of 285 TCs were identified in the 5 countries, with an overall participation rate of 62% (n = 176), the country with the highest rate of acceptance was Mexico with 100%; Brazil had the lowest participation rate with 46.5%. Was not possible to contact by any means 27% (n = 77) of the TCs, and 11% (n = 32) did not wish to participate in the study (figure 1). Table 2 shows the distributions and answers of TCs classified by country.

Health services provided

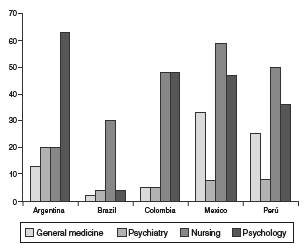

Health services outlined in our questionnaire included the staff's weekly schedule in general medicine, psychology, psychiatry and nursing. Nursing worked longer hours, with an average of 41 h/week, with values ranging between 4 to 168 h/week, followed by psychology services, that had a workload of 39 h/week. Psychiatry had the lowest time intensity, with an average of 9 h/week ranging between 4 h/week in Brazil to 20 h/week in Argentina. Figure 2 shows the weekly different time intensities depending on the country.

Abuse problems treated

Regarding the type of disorders treated, patients with disorders of substance abuse was the most reported, accounting for 98% (n = 170) of the TCs, followed by alcohol abuse treatment with 94% (n = 164), and 40% (n = 70) of the TCs treated other abuses including compulsive gambling, sex offenders and law offenders. Figure 3 shows the various abuse problems treated by country.

Abandonment reasons

The most common reasons for patients to leave the treatment were similar in all countries, being the main one "not accepting institution guidelines" (31%), followed by "lack of financial resources" (30%), and "not feeling good in the institution" (28%). Less frequent reasons were also homogeneous across countries; the most uncommon one was not liking the staff of the TC (10%) (figure 4).

De Leon criteria individual score

Individual performance results for each of the De Leon criteria which were showing the highest and lowest compliance by each TC were accounted (Table 3). Most criteria were met by more than 90% of TCs in the sample; the most frequently met in the 5 countries were "community activities", "awareness training" and "personal growth training". The least accomplished criteria were highly variable between countries, being "planned duration of treatment" (75%) in Brazil, "separation from the community" (47%) in Colombia, "staffroles and functions" (35%) in Mexico, "separation of the community" (72.3%) in Peru, and "residents as a role model" (55%) in Argentina.

Overall quality of TCs according to the De Leon criteria

Having the number of criteria met and TCs that reached them, 61% of the participant communities met 11 or all of the De Leon criteria according to the inquiry realized. It can be seen that only in Colombia and Argentina communities that met 8 criteria or less were found, while in Brazil more than half of the communities surveyed met the 12 criteria established in our inquiry (Table 4).

Discussion

Our study results evaluate that, at Latin American level, the TCs are highly widespread and established, and are mostly registered in national bodies responsible for regulating them. One of the first findings is that the establishment of the TCs was unrelated to the number of inhabitants of a country, because one with the highest number of inhabitants, like the Brazilian (State of Sao Paulo), had less TCs available than countries with fewer inhabitants, like Peru; this may be because Peru has already conducted several training programs for the use of such strategies 15 or the existence of underreporting of TCs with regulators.

The response rate of the TCs willing to participate was similar to studies done in other places, such as in a study conducted in Europe and USA, (16 which had a response rate of approximately 64%, while our study had an average of 61%. This response rate limits the external validity of the data and its ability to identify the strengths and weaknesses of TCs, and with it the development or generation of public health policies to improve these facilities. Among those TCs not responding it can be assumed to have an organization that does not meet the standards for these types of facilities. However, in countries like Colombia some of the not respondents are affiliated with the FLACT, which suggests a minimum quality. Also in Mexico (Estado de Guadalajara) there is a 100% response enabling better decisions.

Another result of our study was the workload of health professionals working in the TCs. Although the results were not very homogeneous, it was found that despite the variability of countries included, the nurse has the highest workload, probably as a result of these professionals performing day and night shifts for proper care the patients. Another highlight was the low workload of the psychiatry specialists, despite being one of the health professionals that should be more involved in the integrated handling of patients with a disorder of abuse or substance dependence.9,14 These findings are consistent with results of studies conducted worldwide, as performed by Jacob et al. (2007), in which it was found that there is a shortage of nurses and trained mental health physician and a deficiency of beds and institutions specializing in management of mental illness. (17 Another reasonable explanation is that, despite having specialized professionals, working conditions may not be ideal for them or not have enough budget to hire them for a longer shift.

The pathologies most frequently treated by TCs were substance abuse disorders, followed by alcohol abuse and other kinds of abuse, which varied slightly depending on the country, except in handling those classified as other abuses. This result is in line with global reporting, in which it has been seen that most of the patients treated in these communities is for use or abuse of any substance different to alcohol.15,18

The most common reason for abandonment identified in our study was not to accept the rules of the institution, which is similar to that reported by Lopez-Goni et al.,19 who encountered the same reason for abandoning these programs. The least frequent reason in our study was not liking the CT staff, a result that was also found by those authors. It is striking that among the reasons for abandonment found in our study, the need to consume drugs or substances was not found among the most prevalent reasons.19,20

The score of the majority of the TCs included in the study exceeds or equals 10 points according to the De Leon criteria, however, is difficult to compare these results with others performed, because this is the first study evaluating the quality of the TCs using these criteria, being the following the most met by the institutions: "community activities", "personal growth training", and "establishment of a structured day"; the least met criteria in our sample were "separation of the community" and "residents as a role model".

In a study conducted in England on TCs, it was found, that although they did not use the De Leon criteria, a similar one was employed and the most met were "behaviors feedback", "living and learning in community", and "established staff functions"; and less frequently met were "the lack of personnel", "groups meeting daily", and "activities among residents".21

In another study by Goethal et al. (2011), European and American TCs were compared through the questionnaire of Essential Elements of the Therapeutic Community, evaluating the performance of elements like "TCs perspective", "structure of treatment", "community as a therapeutic agent", and "therapeutic formal elements and processes". That study found that European TCs met mostly those elements of patient participation and the role of the family in the treatment, especially in the traditional European TCs.16

Among the strengths of our study, it highlights the use of a representative sample of the region, including 5 countries and 174 TCs, which allows us to evaluate and find the similarities and differences between the TCs in the region, becoming one of the larger samples carried out for this type of study. Additionally, it is the first study in Latin America evaluating the quality of the TCs at a regional level, allowing studies to compare our results with other regions of the world, being possible to establish the infrastructure available in the region for the design of future studies on TCs.

Among the weaknesses of our study, we should note the high non-response rate, which was approximately 41%, indicating a lack of collaboration of these institutions to identify all their strengths and weaknesses. Also the methodology of self-reported methodology of each the communities adds bias to the results due to the exclusion of the results of the excluded and communities and also reporting the bias because the directors may avoid informing the negative qualities of their communities. The failure to classify the type of the TCs, that is, if the TC was performed in a prison or if its orientation was merely spiritual or scientific, was not clear in our study, unlike those made in Thailand, (18 Europe, and USA,16; however, De Leon criteria numbers 2 and 3 include a spiritual focus, so that much of the TCs met with them infer that participating institutions have a mixed orientation in their processes treatment.

As we can see, the Latin American region has a considerable number of TCs meeting the quality criteria proposed by De Leon, but it is needed to assess the acceptance and usefulness of TCs by its users and working staff. Based on these results, we will lead a second phase exploring the impact generated by TCs in the same 5 countries, whose sample is taken from the TCs identified in this study.

Conclusions

Our study has identified in a representative sample the quantity and quality of the TCs available in our region and their main strengths and weaknesses, which could be used in future studies, and could be useful in the generation of new health policies public to standardize, homogenize and improve treatment plans and management of TCs in Latin America.