Over recent decades, both the general public and the scientific community have taken great interest in mindful ness due to its potential as a psychological technique for a range of clinical problems (Perestelo-Perez et al., 2017). Dispositional mindfulness is an innate tendency in which individuals continuously pay attention to experiences hap pening in the present with openness and non-judgement. It has been linked to reduced reactivity and better emotional response recovery (Roemer et al., 2015), as well as lower in dicators of psychopathology, such as depressive symptoms, rumination and catastrophizing (Tomlinson, 2018). Disposi tional mindfulness has also been identified as a mediating variable between anxiety and performance in young peo ple (López-Navarro et al., 2020). Similarly, skills developed through mindfulness practice have been related to lower rates of depression and anxiety symptomatology in adults (Parmentier et al., 2019) and lower rates of anxiety (Moix et al., 2021), depression, paranoia, and sensory stress in adolescents (Díaz-González et al., 2018)

Although there is currently a significant body of evidence supporting the notion that mindfulness-based protocols are effective for the treatment of anxiety, stress (Madson et al., 2018) and depression (Bonde et al., 2022), research has continued to steadily explore how mindfulness could benefit different psychological processes and related mechanisms.

A variable of particular interest in mindfulness research is repetitive negative thinking (RNT), which is a global pro cess of intrusions comprising rumination, worry, and post-event processing that has been widely linked to the main tenance of multiple psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression (Frank & Davidson, 2014; Ruiz et al., 2021). RNT has been conceptualized as a pattern of uncontrollable, intrusive, negative, and repetitive thoughts from which an individual cannot disengage easily (Ehring & Watkins, 2008). RNT is present in a wide range of clinical problems, which suggests that diverse disorders share common features of this process with only the contents of the thought differing from one disorder to another. RNT can therefore be consid ered a transdiagnostic process (Ehring et al., 2011).

Mindfulness skills contrast with typical RNT functioning. Intentional and sustained attention on the present moment opposes a fluctuating attention on past (rumination and post-event processing) or future events (worry). Mindfulness promotes a flexible and voluntary attentional deployment toward various chosen stimuli, whereas in RNT, attention is usually rigid, sustained and problem oriented. Similarly, a mindful attitude promotes a compassionate and non-judg mental approach, which is radically different from RNT’s outlook, which generally concerns judgmental and self-crit ical thoughts (Borders, 2020).

Mindfulness skills encourage a change of perspective that allows people to observe their experiences without becoming part of them. Scholars have given this ability dif ferent names, for example “decentering or reperceiving” (Shapiro et al., 2006), detachment (Shapiro, 1992) and cog nitive defusion or self-as-context (Ruiz et al., 2021). When people have little perspective or are “attached” or “fused” to their own experiences, thoughts, and other private events such as emotions and memories, these can exert dominance over overall behaviour, limiting sensitivity to contextual contingencies and causing psychological distress (Ito et al., 2021). However, there is little evidence on how these psychological processes affect, mediate, and moder ate general mindfulness skills. For example, reperceiving or decentering often overlap with indicators of mindfulness, so it is important to clarify whether these concepts refer to the same skill or not (Carmody et al., 2009).

Various studies have reported positive relationships be tween mindfulness and optimized functioning of different executive functions. For example, mindfulness has been as sociated with greater response inhibition capacity (Gallant, 2016); greater executive control by alleviating emotional interference on cognitive functions (Huang et al., 2019); greater attention and impulse control (Bueno et al., 2015); and improvements in visuospatial processing, working mem ory and general executive functioning (Zeidan et al., 2010). Tortella-Feliu et al. (2018) compared differences between meditators and non-meditators on variables such as effort ful control (an aspect related to executive attention, which includes the ability to voluntarily manage attention, inhibit a dominant response and activate a subdominant response while experiencing an emotion) and dispositional mindful ness. Their results indicate that meditators scored higher than non-meditators on indicators of attentional and inhib itory control, as well as on other facets associated with dispositional mindfulness.

Given the heterogeneity of the mediators and mecha nisms involved in mindfulness, there is a need for further study on possible processes of change, indicating that new research on mediators for mindfulness would be valuable (Burzler et al., 2019; Monteregge et al., 2020).

MacKinnon (2007) proposes two different types of medi ation studies. The first, employed after a relation between two variables has been identified, seeks to determine how a certain effect occurs through the inclusion of a third var iable to improve understanding of the relation or to de termine whether it is spurious. This third variable can be considered mediating because it is part of the causal se quence of the observed relation. The second type of medi ation study uses theory concerning the mediation approach to design experiments that allow for the alteration or mod ification of variables hypothesized to be causally related to the dependent variables. These studies therefore tend to involve an intervention with control groups.

We decided that the first type of mediation study out lined above was more appropriate for the present study be cause, rather than testing the mechanisms associated with a change in a given intervention, it allows us to examine poten tial mediators in order to test and refine theories, including with cross-sectional or longitudinal data (MacKinnon, 2011).

There have been studies that have tried to clarify the relationship between RNT and dispositional mindfulness (Petrocchi & Ottaviani, 2016), however, to our knowledge, no studies have attempted to understand the value of RNT as a mediating variable between such dissimilar aspects as cognitive fusion and effortful control.

The present study aims to explore the associations be tween dispositional mindfulness, effortful control and cog nitive fusion by proposing repetitive negative thinking as a possible mediating variable using bootstrapping methods. We formulated the following hypotheses: (1) dispositional mindfulness will be negatively associated with RNT and cog nitive fusion, (2) dispositional mindfulness will be positively associated with effortful control, (3) RNT will be positive-ly associated with cognitive fusion and negatively associ ated with effortful control, and (4) RNT will mediate the relationship between dispositional mindfulness, effortful control, and cognitive fusion.

Method

Participants

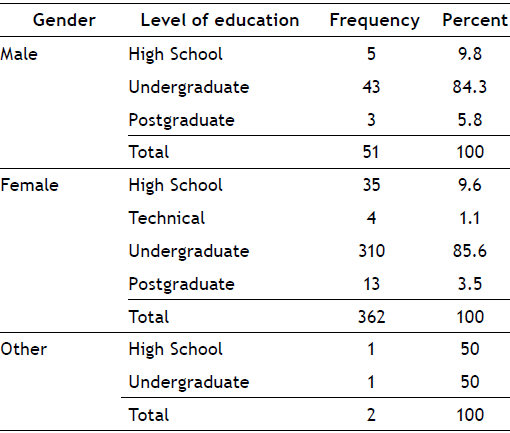

415 people over 18 years of age were recruited through a public call for participants at a Spanish university. Of the total number of participants, 51 were male, 362 were fe male and 2 were of another gender. The majority report ed a university level of education (353). The mean age of the participants (N = 415, SD = 3.72) was 20 years, with ages ranging from 18 to 47 years old. Table 1 shows the frequen cy distribution of gender and level of education.

Procedure

Between November and December 2021, a call for par ticipants was made on a communication platform of a Span ish university for an experiment about mindfulness and associated psychological variables that could be complet ed online. Participation was voluntary and unpaid. Study participants received one academic credit that could be used toward various courses. The lead author designed the assessment battery. Informed consent and questionnaires for the study were available through the Qualtrics platform for both mobile devices and computers and were presented in the same order as laid out below. The average time to complete the survey was 44.5 minutes. Device configura tion required the completion of all items so there were no missing data.

Measures

Five Facets of Mindfulness Questionnaire Short Form (FFMQ). The FFMQ (Baer et al., 2012) was used to assess dispositional mindfulness. The questionnaire consists of 24 Likert-type items in which participants are asked to respond to questions on situations in their lives using a scale from 0 (never) to 5 (always). FFMQ covers five factors: observing, describing, acting with awareness, not judging inner expe rience, and not reacting to inner experience (Baer et al., 2012). The FFMQ has shown adequate levels of reliability and there is acceptable evidence of its validity (Sosa & Bi anchi-Salguero, 2019).

Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire (PTQ). The PTQ (Ehring et al., 2011) was used to assess repetitive negative thinking. The questionnaire consists of a 15-item Likert-type scale in which participants respond to statements on the frequency of repetitive negative thinking on a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (almost always). It assesses the different facets of the RNT process, namely repetitiveness, intrusiveness, difficulty of stopping, unproductiveness, and the extent to which it captures or interferes with mental capacity. The reliability indices of the scores on this scale are adequate and the validity of this instrument has been proven for var ious populations (Devynck et al., 2017).

Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire (CFQ). We included the CFQ (Gillanders et al., 2014) to assess cognitive fusion. The questionnaire consists of 7 Likert-type items, using a scale from 1 (never) to 7 (always). It produces a general measure of cognitive fusion, which is a verbal cognitive pro cess in which individuals become “entangled” with their own thoughts, evaluations, memories, and emotions. It has been observed that cognitive fusion can lead to the imple mentation of experiential avoidance and suppression strat egies, what worsens emotional symptoms, mindfulness, and life satisfaction. Studies have demonstrated the good psy chometric properties of Spanish-language versions of the CFQ (Ruiz et al., 2017).

Effortful Control Scale (EC). We employed the EC (Ev ans & Rothbart, 2007) to assess effortful control. The EC is part of the Adult Temperament Questionnaire (ATQ) short form which was developed to obtain a number of clinical indicators associated with temperament. Effortful control is related to executive attention and includes the ability to voluntarily manage attention, to inhibit a dominant re sponse and to activate a subdominant response while expe riencing emotion. The Effortful Control subscale consists of 19 items to be rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strong ly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). EC is divided into three subscales: inhibitory control (7 items), attentional control (5 items) and activation control (7 items). This instrument shows acceptable levels of internal consistency, temporal stability and convergent validity (Tortella-Feliu et al., 2013).

Data analysis

All analyses were performed using the open-access sta tistical software JASP v0.16.4 (2022). The first step was to perform normality analyses using the Shapiro-Wilk test, which showed that all variables presented a normal distri bution, except for the cognitive fusion variable. We then implemented correlation and mediation analyses to ex plore the existence of indirect effects associated with the mediating variable and the relations between them. The mediation analysis was performed using the bias-corrected percentile method (Bootstrap) suggested by Biesanz et al. (2010). This type of analysis makes it possible to make caus al interpretations even in correlational and cross-sectional designs, if these are supported theoretically and with ade quate substantiation (Hayes & Preacher, 2014).

Results

Correlation analysis

To test the first three hypotheses, parametric tests (Pearson’s) were employed to estimate correlations be tween the study variables. Statistically significant negative correlations (p < .001) were identified between mindfulness (FFMQ), repetitive negative thinking (PTQ), and cognitive fusion (CFQ), and between RNT and effortful control (EC). Positive correlations were identified between mindfulness and effortful control and between RNT and cognitive fusion (p < .001). Figure 1 shows a heat map of all the correlations to facilitate the visual analysis of these results.

Cognitive fusion and RNT both show strong associa tions with mindfulness, and on the basis of these results we decided to apply a mediation model to test our fourth hypothesis.

Mediation analysis

Following Baron and Kenny’s (1986) model for statistical ly testing mediation, we implemented bootstrapping meth ods which apply a non-parametric approach to sensitively determine how an independent variable indirectly affects the dependent variables through a mediator. Bootstrapping methods have certain advantages in testing indirect ef fects compared to classical parametric analyses such as the causal step approach or the Sobel test (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007). For example, they do not involve any of the assump tions required of other types of analysis and they also tend to perform better with small samples in terms of statistical power and type 1 errors. For these reasons they are one of the preferred methods for making causal inferences (Hayes & Preacher, 2010).

The indirect effect is calculated on the basis of the re sampling with replacement, and a sampling distribution is then generated empirically. For this analysis the effects were tested on the basis of the standard errors of 5000 bootstrap samples. This allowed us to estimate p-values of the model test statistics and standard errors of the param eters under non-normal data conditions (Nevitt & Hancock, 2001). To determine whether the gender of the participants affected the relations identified in the model, this variable was introduced as a possible moderator with no change in the effects between the observed variables. Figure 2 pre sents the results of the mediation model with a 95% confi dence interval.

Figure 2 Mediation model showing relations between repeti tive negative thinking (PTQ), dispositional mindfulness (FFMQ), cognitive fusion (CFQ) and effortful control (EC).

Direct effects. Direct effects represent the impact made by the independent variable on the dependent varia ble through the presence of the mediator. All direct effects of mindfulness on the dependent variables were found to be significant: cognitive fusion (M = -.134, SE = .026, CI 95%: -.187, -.080, p < . 001) and effortful control ( M = -.021, SE = .004, CI 95%: .012, .029, p < .001).

Indirect effects. Indirect effects represent the impact made by the independent variable on the dependent var iable through the mediating variable. In this regard, dis positional mindfulness affects cognitive fusion negatively (M = -.362, SE = .028, CI 95%: -.422, -.306, p < .001) and ef fortful control positively (M = .010, SE = .002, CI 95% .004, .015, p < .001) through the mediator, RNT.

Total effects . Total effects represent the impact made by the independent variable on the dependent variable without mediator involvement. We found that dispositional mindfulness affects cognitive fusion (M = -.0497, SE = .030, CI 95%: -.554, -.434, p < .001) and effortful control (M = .031, SE = .003, CI 95%: .024, 0.037, p < .001) significantly, with confidence intervals that did not overlap with zero. Details of these results are presented in Tables 2, 3 and 4.

Table 2 Direct effects

Delta method standard errors, bias-corrected percentile bootstrap confidence intervals, ML estimator.

Table 3 Indirect effects

Delta method standard errors, bias-corrected percentile bootstrap confidence intervals, ML estimator.

Table 4 Total effects

Delta method standard errors, bias-corrected percentile bootstrap confidence intervals, ML estimator.

Effect size. Following the recommendations made by Cheung (2009), the standardized indirect effect value was used to measure the effect size because it is one of the most appropriate parameters for effect-size measures in media tion analyses. This estimate can be interpreted following the conventions suggested by Cohen (1988) where values of 0, 0.14, 0.36 and 0.51 correspond to effect sizes “zero”, “small”, “medium” and “large”, respectively (Cheung, 2007). In our model, we found a medium effect size for mindfulness, RNT and cognitive fusion (-.36; CI: -.422, -.306, p < .001) and a small effect size for mindfulness, RNT and effortful control (.010; CI: .004,.015, p < .001).

Discussion

In this sample of young people, statistically significant positive relationships were found between dispositional mindfulness and effortful control and negative relationships were found between mindfulness and cognitive fusion. RNT was positively associated with cognitive fusion and nega tively associated with effortful control. These results are compatible with our first three hypotheses, which in turn are consistent with the theoretical proposals of mindful ness and acceptance-based models such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Metacognitive Therapy, in which verbal or metacognitive mechanisms such as decentering or defusion are seen as central elements of healthy psycholog ical functioning (Bernstein et al., 2015; Ruiz et al., 2021).

In regard to our last hypothesis about the possible me diating role of RNT, it seems that RNT acts as a partial me diator between mindfulness, cognitive fusion, and effortful control, meaning that dispositional mindfulness might exert part of its influence through the mediator (RNT), but that it also might directly influence effortful control and cogni tive fusion. This contrasts our hypothesis on the important mediating role played by repetitive negative thought. How ever, this result is not surprising, since, as Baron and Kenny (1986) have pointed out, at least in the field of psychology, complete mediation is rare due to the prevalence of multi ple mediators. This leaves the door open for further studies to identify additional potential mediators.

This result is also consistent with research showing that mindfulness training may improve self-compassion and psychological health in young people (Joss et al., 2019) by bringing an exploratory attention to the present experi ence that facilitates opportunities to explore one’s habits of mind in more depth, and reduce attempts to control or manipulate cognitive and affective experiences (Santarnec chi et al., 2014) and decrease the cognitive interference associated with this RNT process (Harper et al., 2022). All of these findings could be of particular interest for educators and clinicians who work with related issues.

According to Parmentier et al. (2019), worry and rumi nation are two of the most potent mediating variables be tween mindfulness and symptoms of anxiety and depres sion (compared with other emotional regulation strategies such as reappraisal and suppression). Likewise, dispositional mindfulness has been negatively related to mental health problems, with this relationship being mediated by process es such as decentering and self-acceptance, which position decentering as key to understanding the mechanisms as sociated with the effects of mindfulness (Ma & Siu, 2020).

Decentering and defusion are both variables linked to mindfulness (Brown et al., 2015; Hayes et al., 2014; Vanzhu la & Levinson, 2020). These two variables could be consid ered analogous, as they differ only in the nuances of their conception and both constitute the result of a sequence of processes that are altered through mindfulness skills, whether these be dispositional or developed through ther apeutic exercises.

Assaz et al. (2018) propose that this type of mechanism could be analysed using a basic process approach in order explain the changes associated with the implementation of strategies that promote processes such as defusion. The changes are thought to occur because different mecha nisms such as responsive extinction, counterconditioning, inhibitory learning, differential reinforcement, and the introduction of verbal cues work together to reduce the influence of verbal relations on other behaviours. This ap proach, based on processes of change, represents a new paradigm in clinical psychology. It moves forward from a nomothetic approach towards the identification of common modifiable elements that currently make up different ther apeutic strategies, facilitating the integration of multiple theoretical orientations as part of an integrative proposal that uses an evidence-based practice approach (Hofmann & Hayes 2019; Sanford et al., 2022).

The limitations of this study must be taken into account when analysing its results. Even though we controlled for the gender variable in our analyses, most of the partici pants in the sample were female. This could represent a behavioural bias in the observed variables, because gender differences have been reported in several indicators asso ciated with psychological functioning and mental health (Matud et al., 2019). Likewise, the mean age did not exceed 20 years, which makes it difficult to generalize these results to other types of populations and contexts. Accordingly, fu ture research could consider strategies to ensure that the sample of participants is better balanced, and its age range expanded, in order to be able to identify possible differenc es associated with the participants’ gender and age in the indicators of dispositional mindfulness, repetitive negative thinking, effortful control and cognitive fusion.

The high correlation between repetitive negative think ing and cognitive fusion needs to be analysed. This result could reflect three different hypotheses. First, it could sim ply be related to the measurement instruments used, due to the measures’ insufficient discriminant validity for as sessing both the PTQ and the CFQ (Valencia, 2020). Second ly, the high correlation could indicate an overlap between variables, in which case they would be measuring aspects of the same construct that encompass both elements, as is the case of experiential avoidance (Mansell & McEvoy, 2017). The last possible explanation assumes that both re petitive negative thinking and cognitive fusion are part of the same pattern of inflexible behaviour, distinguishing the former as a process that involves changes in covert behav iour (thoughts) under the influence of contextual events, while cognitive fusion would be the result of this series of behavioural events. In any case, the close relationship found in this study between the two constructs does not allow any firm conclusions to be drawn on the extent of the results until the relation between these two variables is determined.

Taking into consideration that in certain cases, patients with high levels of RNT tend to be less responsive to treat ment (Lewis et al., 2021), the identification of RNT and its subtypes (rumination, worry and post-event processing) as possible mediating variables of the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and other mechanisms involved in the maintenance of psychological problems may represent possibilities for improving the effectiveness of treatments. This also reinforces the idea that RNT should be considered a transdiagnostic process and therefore an intervention tar get to be considered in psychological treatments (Watkins & Roberts, 2020).

Future research could explore whether treatments fo cused on transdiagnostic processes common to various clin ical problems, such as RNT, are comparable to protocols designed for specific diagnoses, examining the acceptability of their response and maintenance rates, and what process es of change are altered through their implementation. Al though RNT has been predominantly studied in the context of disorders such as anxiety and depression, it is necessary to consider the role it may play in other types of medical and psychological problems, as there is a growing body of evidence pointing to the presence of this process in patients with epilepsy (Whitfield et al., 2022), insomnia (Cheng et al., 2020), fatigue (Leung et al., 2022), and substance abuse (Hamonniere et al., 2022), as well as in the emo tional symptomatology associated with mothers in the perinatal period (Moulds et al., 2022)1 2 3.