Introduction

Precision Agriculture is based on the knowledge and quantification of the spatial variability of yield limiting factors. Soil compaction is a complex physical process that affects the crop performance by limiting the expansion of the roots and the reduction of water and nutrients uptake from soil (Hamza & Anderson, 2005). Cone penetrometers have been widely used to assess soil compaction at field conditions because cone index (CI) is an inexpensive way to monitor and assess soil compaction and it is closely related to the pressure encountered by roots (Adamchuk, Ingram, Sudduth, & Chung, 2008; Carrara, Castrignanò, Comparetti, Febo, & Orlando, 2007; Jabro, Iversen, Stevens, & Evans, 2015). Values of CI greater than 2 MPa measured at soil water content near to field capacity are regarded as limiting for normal root growth, although there is no agreement about this threshold because it depends on crop species and soil type as well as the shape and dimension of the penetrometer probe (Pilatti, Orellana, de Imhoff, & Silva, 2012).

Due to the spatial variability of soil compaction, the needs for remedial practices may vary within the field, thus mapping the spatial distribution of soil compaction is a key component of site-specific tillage management (Basso et al., 2011). However, mapping the spatial distribution of CI is a challenging task due to the point nature of the measurement and the high spatial and temporal variability (Carrara et al., 2007; Jabro et al., 2015). Furthermore, the small scale of spatial structure in the horizontal plane increases the efforts needed to accurately map the spatial distribution of this soil property (Adamchuk et al., 2008; Castrignanò, Maiorana, Fornaro, & Lopez, 2002; Veronesi, Corstanje & Mayr, 2012).

Data from handheld soil penetrometers have been widely used to develop soil compaction maps relying on 2D (Bonnin, Mirás-Avalos, Lanças, González, & Vieira, 2010; Veronese et al., 2006) or 3D (Castrignanò et al., 2002; Veronesi et al., 2012) interpolation techniques. Among the spatial interpolation techniques applied to CI data, indicator kriging has been reported as an effective way to deal with high spatial variation of soil properties including CI data (Bonnin et al., 2010; Castrignanò et al., 2002).

Rather than working with actual CI values, this technique transforms the target variable into a binary one based on some arbitrary threshold and maps the probabilities of critical value being exceeded at each node of the interpolation grid (Webster & Oliver, 2007). Characterizing the spatial extent and severity of soil compaction with CI measurements could be labor and time consuming thus the probabilistic approach to assess soil impedance should be preferred (Castrignanò et al., 2002).

Our working hypothesis is that the indicator transformation of the CI data from the upper layer (0-30 cm), could be used to map the probability of occurrence of soil compaction which could help to delineate potential tillage zones. Thus, the aim of this research was to examine the spatial variability of CI data in a silty-loam soil form the center of Santa Fe (Argentina) under no-till system, and to delineate zones for site-specific tillage based on occurrence probabilities maps of soil compaction developed by kriging indicator.

Materials and methods

The study was carried out in the experimental field of the Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias (FCA-UNL) located at Esperanza, Santa Fe province (31.4º S, 60.9º W). The soil of the experimental plot has been classified as fine-mixed-thermic Typic Argiudoll Esperanza series, which is characterize by a top mollic layer of 30 cm depth and 48 g kg-1 sand, 667 g kg-1 silt, and 287 g kg-1 clay followed by a 10 cm transitional horizon to an argillic textural horizon with higher contents of clay. The field has been under conventional tillage for more than 50 years and recently it has been turned into no-till system. The previous five seasons were cropped with wheat-soybean sequence under direct planting.

During the fallow 2011, 69 georeferenced cone index (CI) and volumetric water content (SWC) measurements were recorded on a 70 x 110 m experimental area. Sample locations were distributed following a pseudo-regular grid with an average distance of 9 m between samples avoiding visible machinery footprint. Spatial coordinates were registered using a GPS and then projected into the Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) coordinate system zone 20S. At each location, CI measurements from the 0-40 cm layer were taken at 2.5 cm increments with a soil compaction meter (FieldScout(r) SC 900). At the same time, SWC at 0-20 cm depth were logged with a time domain reflectometry based sensor using a 20-cm rod (FieldScout(r) TDR 300). Readings were calibrated using a local calibration function for these soils (Camussi & Marano, 2008).

In order to map the probability of exceedance of the soil compaction threshold, the indicator approach was performed as described by Castrignanò et al., (2002). This approach is based on the interpretation of the conditional probability of exceedance pf the cutoff value as the conditional expectation of an indicator variable (Webster & Oliver, 2007). The indicator variable (I) was created by splitting the sampling locations into two groups based on their CI profiles. The sampling locations having CI values greater than 2 MPa at any depth within 0-30 cm layer were assigned with the value 1, and 0 otherwise.

The spatial structure of the CI data aggregated by 10-cm layers and the indicator variable was assessed by a model-based approach (Diggle & Ribeiro, 2007). Thus, omnidirectional variograms were fitted by the restricted maximum likelihood procedure (REML) and then the spatial structure was tested by the likelihood ratio test (LRT) between log-likelihood of the spatial and the non-spatial model. The model performance was checked by cross-validation procedure computing the correlation coefficient between observed and predicted values (r) and the mean error (ME). In cases where spatial structure was detected, spatial predictions for CI were obtained by ordinary kriging (Webster & Oliver, 2007).

Data management and geostatistical analysis were carried out using the statistical programming language R (R Core Team, 2015) and the packages gstat and geoR (Pebesma, 2004).

Results and discussion

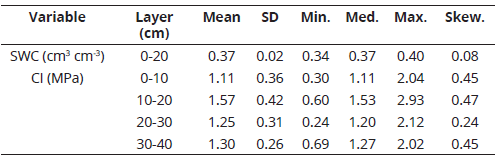

Soil water content showed low variation (CV < 6%, Table 1) and the average water content was near to the field capacity for this soils (Imhoff et al., 2016).

Table 1 Summary statistics of soil water content (SWC) and cone index data (CI) aggregated by 10-cm layers.

SD = standard deviation; Min = minimum; Med = median, Max = maximum; Skew. = skewness.

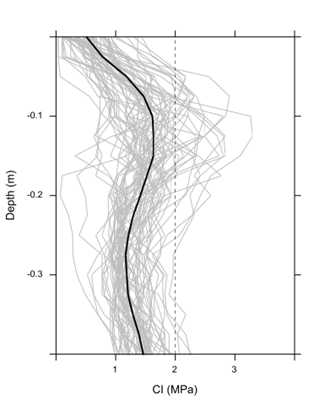

The low variation of SWC could be attributed to the low spatial variation of texture and elevation in this soils (Alesso, Pilatti, Imhoff, & Grilli, 2012). The CI profiles show high degree of variability which decreased with depth (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Cone index profiles of the 69 sampling locations and average profile of the experimental plot.

The CV of CI data aggregated by 10-cm layers ranged from 32% at upper layer to 17% in the lowest layer (Table 1). Sample distribution of CI values showed low positive skewness and no transformations were needed (Webster & Oliver, 2007). Spatial variability of CI is known to be related to changes in soil water content, texture and compaction (Chung, Sudduth, Motavalli, & Kitchen, 2013; Hummel, Ahmad, Newman, Sudduth, & Drummond, 2004). Thus, due to low variation of SWC and texture, the horizontal variability of CI was assumed to be related to the effect of tillage and traffic.

The vertical distribution of the CI values shows an increase of mean CI at about 10-15 cm depth and below 30 cm. Whereas the former could be related to the presence of a plow pan, the later matches the beginning of the transitional horizon of this soil which is characterized by a higher content of clay. However, the overall CI values were below the 2 MPa threshold within the explored depth. Under uniform management approach, the overall soil condition would be regarded as not restrictive for root development and thus no remedial practices would be recommended for this field. As a result, several locations would remain with CI values above 2 MPa within 0-30 cm layer and soil resistance would be still limiting the root development in some parts of the field.

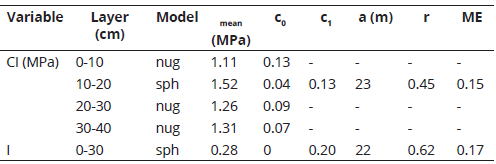

The model-based analysis of the spatial structure of CI data aggregated by 10-cm layers showed significant spatial structure only for the 10-20 cm layer. The estimated nugget: sill ratio indicates that about 77% of the total variance is spatially structured and the range of spatial dependence of CI values is about 22 m (Table 2).

Table 2 Variogram model parameters estimated by restricted maximum likelihood (REML) and cross-validation results for original cone index (CI) data and the indicator transformed data.

Model = spatial covariance model (nug = pure nugget, sph = spherical); c0 = nugget variance; c1 = partial silll; a = range of spatial dependence; r = coefficient of linear correlation between observed and predicted values; ME = mean error.

This results are similar to those reported by authors working in other soil conditions (Bonnin et al., 2010; Castrignanò et al., 2002; Veronese et al., 2006). The spatial prediction map revealed that most of the area has CI values smaller than 2 MPa (Figure 2) and the root development would be restricted at only about 8% of the total area distributed in small spots.

Although this approach allowed mapping soil compaction, it only used the information from the 10-20 layer due to the CI of the remaining layer showed poor spatial structure and could not be interpolated.

The lack of spatial structure observed in the remaining layers is a common feature of soil properties such as soil resistance. In this study, the spatial continuity of this property would be under the sampling scale due to the combination of small scale variations and measurement errors. The spatial variability within plowed layers is the result of natural and anthropic sources of variation whereas spatial variability of soil properties at underlying horizons is commonly related to the natural variation of soil forming factors (Corá, Araújo, Pereira, & Beraldo, 2004; Veronese et al., 2006). Thus, the effects of tillage and machinery traffic are expected to increase soil variability and reduce the spatial dependence of their properties. Alesso et al., (2012), worked on a similar soil but using a coarser sampling scale and found no spatial structure for most of the physical and chemical properties studied, even those less affected by anthropic practices like particle size distribution.

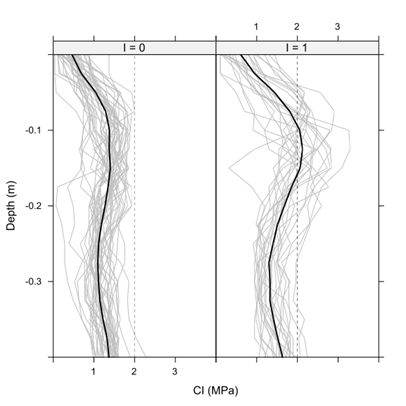

Figure 3, shows the average profile of CI for each indicator group.

Figure 3 Cone index profiles and average profile of each indicator group. I = 1 for sampling locations having CI values greater than 2 MPa at any depth within 0-30 cm layer, and I = 0 otherwise.

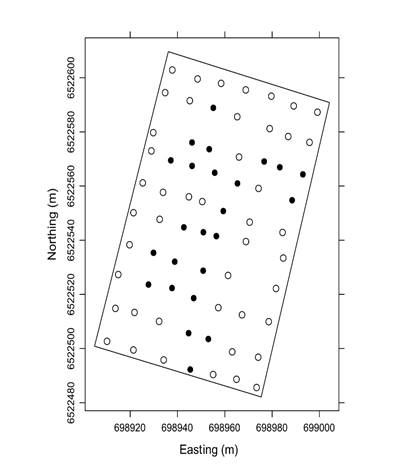

The group with I = 1 shows a marked increase of the mean CI at about 10-15 cm which exceed the 2 MPa threshold indicating compaction issues. In order to alleviate this compaction, it would be necessary to perform a vertical tillage, i.e. chisel plow, with a tillage depth of 20 cm. On the contrary, the mean CI of the remaining group is below the threshold and no tillage would be required. According to the spatial distribution of the indicator variable, the locations having compaction issues tended to be clustered in the middle of the plot suggesting the need for site-specific tillage (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Spatial distribution of the indicator variable. Filled circles (I = 1) are sampling locations having CI values greater than 2 MPa at any depth within 0-30 cm layer, and empty cricles (I = 0) otherwise.

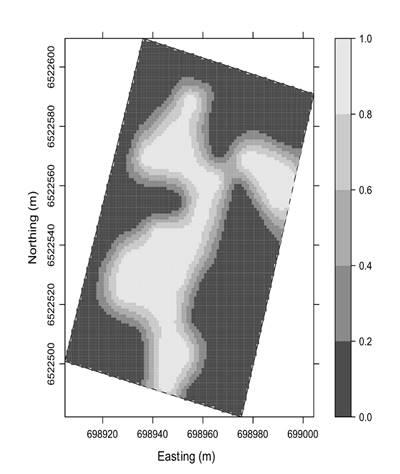

Unlike CI data, the variogram of the indicator variable showed stronger spatial structure with a range of spatial dependence of about 22 m (Table 2). The spatial structure of this variable, which integrates the information of CI from the root zone (0-30 cm), was used to map the probabilities of finding sites with compaction issues by kriging indicator (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Spatial distribution of estimated probabilities of cone index exceeding 2 MPa threshold within 0-30 layer.

This map, shows a wide area in the middle and south part of the experimental plot were the probability of occurrence of compaction issues is high (e.g. probability greater than 80%). However these probabilities decrease quickly and become 0 at few meters due to the short range spatial structure. Bonnin et al., (2010), in their study identified a region within the plot with higher chances of having CI values above the threshold. The authors applied the indicator transformation to each layer and concluded that the spatial distribution of the probabilities were highly variable between layers. Castrignanò et al., (2002), studied the spatial patterns of the probabilities of occurrence of CI above 2.5 MPa using the CI data from the whole root zone and reported high variability of these patterns during the season. These changes were attributed by the authors to the changes of soil water content within the season. In our study, the IC data was gathered at a SWC near to field capacity enabling us to use this information as a reference for the diagnosis of soil compaction issues.

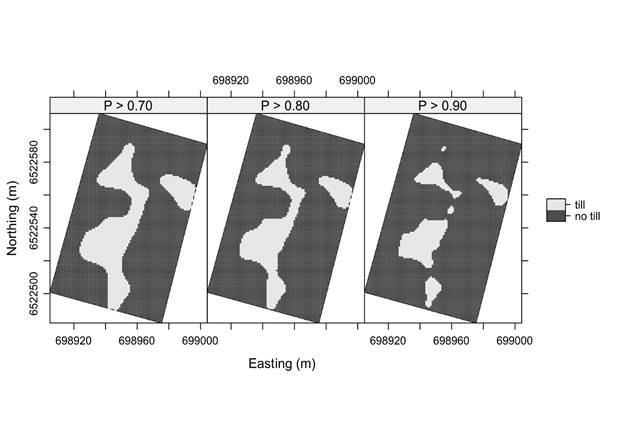

Based on the estimated probabilities showed in Figure 5 and setting a desired cutoff, site-specific tillage prescriptions could be delineated. For example, Figure 6, shows potential management zones for three levels of probability of exceeding the 2 MPa threshold within upper 30 cm layer.

Figure 6 Tillage prescription maps based on the estimated probabilities of CI. exceedening 2 MPa within 0-30 depth obtained by indicator kriging.

There is no recommendations in the literature about the probability levels to be used as a cutoff, thus the values chosen here are somewhat arbitrary. As the probability cutoff increase, the risk of tilling the soil when no tillage is needed decrease and the zones get smaller and patchy. For example, for a probability level of 0.70, the tillage zone represents about 25% of total area whereas by raising the probability cutoff to 0.9, only 13.3% of the area would need to be tilled.

The needs for remedial practices vary within the field and mapping the spatial distribution of soil compaction could help farmers to save fuel, labor, equipment wear and tear (Basso et al., 2011; Carrara et al., 2007). In this study, if the tillage recommendation had made based on the overall soil condition ignoring spatial variability of CI, the root development would remain limited in some parts of the field. On the contrary, by using the prescription maps of the Figure 6 would help to improve the soil management by tilling only the parts of the field where there is high chances to encounter compaction issues.

Conclusion

The high variability and poor spatial structure observed in CI data by layer, limited the application of spatial interpolation techniques based on spatial structure of data. However, maps of the probability of occurrence of soil compaction in the root zone were obtained by integrating the CI data from the arable horizon (0-30 cm) using the indicator kriging approach. Such probability maps could be useful for delineation of potential zones for site-specific tillage in order to save fuel, labor, and equipment wear.