INTRODUCTION

According to the recommendations of the WHO and various scientific associations regarding the use of personal protective equipment when droplet-generating procedures are performed in suspected or positive SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) patients, care guidelines recommend essential protection with high-efficiency respirator (e.g., N95), protective goggles or face shield 1-3. The endotracheal intubation maneuver is considered to be associated with the highest risk for air-borne contamination 4.

In order to foster the adoption of maximum protection measures in aerosol-generating procedures, China and other Asian countries advocate the use of the so-called intubation box or aerosol box, invented by Hsien Yung Lai, a Taiwanese anesthetist. This device has gone through modifications, one of them by anesthesia teams in the United States and Great Britain, consisting in tilting the upper surface in order to enhance visibility 5.

At present, the aerosol box is suggested as ancillary device or in specific instances of personal protective equipment shortages. Therefore, the box must not be used instead of other recommended protection elements 6.

Some anesthetists have reported greater difficulty and, in particular, delay in successful intubation when the aerosol box is used, which they attribute to the added encumbrance to the procedure. Consequently, they suggest the use of a videolaryngoscope as an additional element and, in fact, most protocols recommend using the videolaryngoscope instead of the standard Macintosh laryngoscope in COVID-19 patients 5,6.

Comparisons between the videolaryngoscope and the standard Macintosh laryngoscope in terms of time and successful intubation have shown they are similar when used in the normal airway, as concluded by the latest Cochrane systematic review report 7,8.

Regarding the objective analysis of intubation difficulty or delay with the addition of the aerosol box, there are few references highlighted in the literature. Some papers mention anecdotal cases or make expert recommendations 5,6,9, hence the interest in this study and its contribution.

Based on these reasons, the following question was asked: Does the use of the aerosol box make the endotracheal intubation procedure more challenging and protracted compared to not using it in adult patients with respiratory distress and a diagnosis of COVID-19? The objective of this study was to compare time and difficulty of orotracheal intubation with the use of the aerosol box in patients with suspected COVID-19 in a simulation setting. Orotracheal intubation with videolaryngoscope versus the traditional Macintosh laryngoscope was used to that end.

METHODS

Study design

One quasi-experimental phase and one experimental phase. For the former, average time was compared in intubation procedures with four attempts per participant (videolaryngoscope + box, Macintosh laryngoscope + box, videolaryngoscope and Macintosh laryngoscope) in order to determine the time for each procedure performed by the same participant. For the experimental phase, two parallel comparison groups were considered to compare first attempts, in order to determine efficacy in terms of time and number of attempted intubations using the aerosol box (Figure 1).

For the experimental phase: time measured for the first attempt in each group (in blue); for the quasi-experimental analysis: time comparisons between each of the participants in order (first, second, third and fourth intubations). PPE (face mask, cap, gloves, gown, face shield) and intubation guidewire were used in all of the procedures. SOURCE: Authors.

FIGURE 1 Group organization diagram.

Population and sample

The study conducted by Mallick et al. in 2020 8 - which identified a mean value of 15.7 seconds (SD: 6.33) for the Macintosh laryngoscope and of 32.3 (SD: 12.9) for the videolaryngoscope - was used to estimate sample size. Based on those values, the required sample size would be of 8 participants in each group, accepting an error of a=0.05 and a power of 0.80. However, it is worth noting that with the use of the aerosol box plus the goggles and face shield, there was a likelihood of a 25% time increase, approximately. Therefore, the total population of anesthetists and second and third-year anesthesia residents in a Level IV healthcare institution in Bucaramanga was used as a basis to estimate sample size in order to achieve a representative sample, i.e., higher than 75% (30) 10; this number was estimated at 40 operators. A minimum sample of 30 participants generating a total of 120 procedures was considered, with the final number being 33. Of them, for the comparative experimental analysis, 17 were assigned to the group that used videolaryngoscpy first and 16 to the group that used the Macintosh laryngoscope first so that, according to the results obtained by Kilinç and Çinar in 2019, a power of 0.9891 could be achieved (Figure 1).

Inclusion criteria: anesthetist physician, second or third-year anesthesia resident, more than 2 years of experience in surgery, ICU or emergency care. Exclusion criteria: refusal to sign the consent for video recording or day after night shift.

Procedures

The intubation procedure was carried out by attending anesthetists and second and third-year anesthesia residents who confirmed having performed more than 80 successful intubations in their clinical practice; procedures were performed in the clinical simulation laboratory of the Universidad Industrial de Santander School of Health between September and October 2020. Participants received an explanation from the research team regarding the use of full personal protective equipment and hand washing; a trial intubation was allowed with the airway devices that the participants would be using. The intubation manikin used was the 3B Scientific normal adult airway simulator for tracheal intubation which was programmed to show pulse desaturation 10 seconds into the procedure (alarm); no cough reflex was used.

The aerosol box was the IGLU (SOLMED Qx Ltda.) which is 50 cm wide, 55 cm high and 55 cm long. Supplies and instruments included the adult manikin, a # 6.5 endotracheal tube with guidewire, personal protective equipment (PPE) (goggles, face shield, gown, cap, gloves), a McGRATH™ MAC (Medtronic) videolaryngoscope with a # 3 blade, and Macintosh laryngoscope with a # 3 blade.

Each anesthetist was assisted during the intubation process in each of the procedures by nurses in training as well as nurses specialized in adult critical care who helped with tube passage, pneumoplug insufflation and intubation guidewire removal.

Intubations were performed in the sequence defined according to the group to which participants were assigned, as described in Figure 1. All intubations were performed using the intubation guidewire and PPE (face mask, cap, gloves, gown and face shield).

Randomization

Block randomization was used in order to avoid group unevenness, estimating a total of 32 participants assigned to groups of four (in the end there were 33 participants and the last was assigned to the block of the first participants). Eight groups were created using letters A and B, and the block sequence was selected randomly (random numbers in Excel). The blocks were the following: 1(A-A-B-B), 2(A-B-A-B), 3(B-B-A-A), 4(B-A-B-A), 5(B-A-A-B), 6(A-B-B-A), 7(A-A-B-B) and 8(A-B-A-B). Participants were assigned as they came in; those who were assigned to group A started the intubation sequences with videolaryngoscope + aerosol box, and those assigned to group B would perform the initial intubation using the Macintosh laryngoscope + aerosol box (Figure 1).

Instruments

Participant demographic data were recorded together with intubation time in seconds, measured from the moment the manikin was no longer ventilated until the bag-mask (AMBU) device was connected and the first ventilation was provided (this time was measured by two observers using a video recording, and time averages were used in case of discrepancy). The possibility of data loss was prevented in this way. When the first minute was up (60 seconds), the procedure was interrupted and recorded as failed intubation (those times not being included in the analysis).

Number of attempts: based on direct observation, attempts are listed as the number of times the endotracheal tube is introduced or laryngoscope placement needs to be adjusted. Airway maneuvers and difficulties during the procedure were reported by the anesthetists in a survey (tool).

Data analysis

The database was first built on Excel and then exported to Stata version 12 (Stata Corporation, College Station, USA) for the analysis proposed in accordance with the study objectives.

Participant performance and characteristics are described in accordance with the variables, using central trend for quantitative variables according to parametric or non-parametric distribution (U [SD] or Me [IQR]), and absolute and relative frequencies (percentages) for qualitative variables. Mean times during the procedures were compared in the same subjects using Wilcoxon's test for repeated measurements; the exact Fisher test and the Pearson Chi Square test (categorical variables) and the Mann Whitney U test (numerical variables) were used for comparisons between groups A and B to determine inter-group differences.

With time data used in the first intubation (experimental phase), once the data of the two observers were averaged, crude hazard ratios were calculated using the Cox regression; Kaplan-Meier curves and box and whisker plots were built; a multiple regression model was developed linking variables and taking into account the parameters proposed by Hosmer and Lemeshow, linking the variables with p < 0.25 in the bivariate analysis; variables which did not create a change of more than 20% in the "group assigned to Macintosh" were removed, using the Wald test to compare the model with and without the variable. Model fit was assessed.

Ethical considerations

The study was endorsed by the institutional Bioethics Committee of Universidad de Santander, as evidenced in Minutes 012 of June 2, 2020; all of the participants signed the informed consents and bioethical principles (confidentiality, autonomy, beneficence and non-maleficence) were respected.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Thirty-three healthcare professionals participated, 18 of them males (54.55%), with a mean age of 35 years (31.5-54), 13 years of experience as physicians (7-28), and 8.5 years of experience as anesthetists (5-25); 29 worked in surgery (87.88%) and 4 in the ICU (12.12%); 9 were second or third-year residents (27.27%). Regarding difficulties, 16 participants reported issues with the aerosol box (48.48%), 10 reported fogging of the goggles (30.30%), 10 had issues with table height (30.30%), and 5 with the use of the videolaryngoscope (15.62 %). A total of 132 intubations were performed, 121 of which were successful on first attempt, 5 in the second attempt, and 6 failures (>60 seconds); there were no failed laryngoscopies in the cases in which only the Macintosh was used (Table 1).

TABLE 1 Characteristics and mean scores for endotracheal intubations by anesthetists of a Level IV healthcare institution in Bucaramanga (2020).

| Characteristic | N | With aerosol box | Without aerosol box | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (33) | Video | Mac | Difference | P | Video | Mac | Difference | P | |

| % (n) | µ(SD) | µ(SD) | µ(SD) | µ(SD) | µ(SD) | µ(SD) | |||

| 30.44 (9.76) | 26.36 (5.77) | 2.85 (7.69) | 0.0471 | 22.37 (6.25) | 20.12 (4.01) | 2.70 (5.28) | 0.0209 | ||

| Age | |||||||||

| Me (IQR) | 35 (31.5-54) | ||||||||

| Tercile 1 (25-32) | 34.38 (11) | 32.11 (11.73) | 26 (6.12) | 5.66 (10.4) | 0.1094 | 23.09 (5.66) | 20 (2.93) | 3.09 (4.90) | 0.0654 |

| Tercile 2 (33-41) | 34.38 (11) | 27.4 (4.29) | 24.3 (4.47) | 2.11 (4.16) | 0.1712 | 20.72 (6.34) | 19 (3.77) | 2 (5.65) | 0.4724 |

| Tercile 3 (52-65) | 31.25 (10) | 33.77 (11.04) | 28.66 (6.55) | 2.62 (4.83) | 0.2614 | 24.66 (6.12) | 21.8 (5.02) | 3.77 (5.54) | 0.0482 |

| Years of experience as anesthetist | |||||||||

| Me (IQR) | 8.5( 5-25) | ||||||||

| Tercile 1(1-6) | 40.91 (9) | 30.44 (12.21) | 26.5 (5.01) | 3.62 (10.5) | 0.3967 | 24 (7.76) | 19 (4) | 5.75 (5.75) | 0.0346 |

| Tercile 2 (8-20) | 27.27 (6) | 32.4 (8.93) | 27 (7.18) | 4.2 (5.26) | 0.2249 | 21.83 (4.49) | 19.33 (2.42) | 2.5 (5.57) | 0.2932 |

| Tercile 3 (22-32) | 31.82 (7) | 33 (12.32) | 27.83 (5.49) | 1.2 (4.49) | 0.6858 | 25.66 (7.25) | 23.28 (5.12) | 3.5 (6.71) | 0.2342 |

| Position | |||||||||

| Anesthetist | 72.73 (24) | 31.09 (11.00) | 27.18 (5.34) | 2.45 (8.26) | 0.2310 | 23.47 (6.86) | 20.34 (4.25) | 3.81 (5.85) | 0.0102 |

| Second-year resident | 15.15 (5) | 28.25 (4.71) | 21.2 (2.04) | 7.25 (3.59) | 0.0679 | 19.2 (2.16) | 19.8 (2.04) | -0.60(1.14) | 0.2673 |

| Third-year resident | 12.12 (4) | 28.66 (3.21) | 29 (9.53) | -0.33 (6.80) | 1.0000 | 20 (4.32) | 19.25 (5.12) | 0.75 (2.21) | 0.4537 |

| Experience in procedures with videolaryngoscope | |||||||||

| 0-5 | 25.00 (8) | 28.66 (4.32) | 23.87 (4.32) | 5.66 (5.08) | 0.0458 | 22.75 (6.08) | 20 (2) | 5.5 (8.14) | 0.7217 |

| 6-10 | 15.63 (5) | 35.6 (12.21) | 30 (1.63) | 0.5 (4.65) | 0.8527 | 26.5 (6.45) | 23.6 (6.65) | 8.75 (9.03) | 0.0656 |

| 11-14 | 6.25 (2) | 32 (1.41) | 34 (4.24) | 0.8 (1.20) | 0.3173 | 26.5 (6.36) | 19.5 (0.7) | 5.5 (4.94) | 0.1797 |

| > 15 | 53.13 (17) | 30.2 (10.72) | 25.68 (6.03) | 4.2 (7.77) | 0.0326 | 21.35 (5.91) | 19.43 (3.72) | 8.6 (9.28) | 0.1943 |

| Difficulty | |||||||||

| Goggle fogging | 31.25 (10) | 20.22 (3.59) | 28.33 (3.84) | 1.88 (4.25) | 0.3416 | 25.11 (6.25) | 20.3 (4.02) | 5.88 (5.57) | 0.0174 |

| Special difficulty with the videolaryngoscope | 15.63 (5) | 36.8 (13.31) | 27 (3.67) | 9.8 (12.02) | 0.0796 | 24.75 (8.18) | 23 (5) | 3.5 (8.42) | 0.8539 |

| Special difficulty with the aerosol box | 48.48 (16) | 31.84 (10.35) | 27.28 (6.98) | 3.5 (9.07) | 0.1813 | ||||

| Difficulty with table height | 30.30 (10) | 33.4 (11.48) | 28.1 (7.03) | 5.3 (9.71) | 0.0922 | 22.4 (7.10) | 19.1 (3.84) | 3.3 (5.86) | 0.1016 |

| Number of attempts | |||||||||

| 1 | 121 | 30 | 30 | 29 | 32 | ||||

| 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Failed | 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | ||||

| Total | 132 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | ||||

Wilcoxon test p value. n(SD): Mean (standard deviation). Me (IQR): Median (Inter-quartile range). PPE (face mask, cap, goggles, gloves, gown, face shield) and intubation guidewire were used in all procedures.

SOURCE: Authors.

Comparisons with the use of the aerosol box

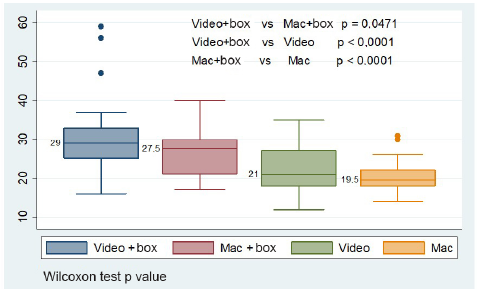

Mean procedure time was estimated without including failed data 6. With the box, time in seconds increased: mean time for the McGRATH™ MAC (Medtronic) videolaryngoscope was 7.57(SD: 8.33) and 6.62 (SD: 5.74) for the Macintosh. When times using the box were compared, the videolaryngoscope required more seconds than the Macintosh (30.44 [SD: 9.76] vs. 26.36 [SD: 5.77], p = 0.0471, with a diference of 2.85 [SD7.69]) (Table 1); a similar result is found when using median comparisons (29 [25-33] vs. 27.5 [21-30], p = 0.0471). Median comparisons for procedures with and without the use of the box show significant differences, with p < 0.05 (Figure 2).

Video: Videolaryngoscope. Mac: Macintosh. Box: aerosol box. PPE (face mask, cap, goggles, gloves, gown and face shield) and intubation guidewire were used in all the procedures. Wilcoxon test p value. SOURCE: Authors.

FIGURE 2 Comparación de medianas según los equipos utilizados para el procedimiento de intubación.

The highest mean scores are found for the participants who reported a special problem with the videolaryngoscope and difficulties with table height. A difference was identified when comparing the videolaryngoscope versus the Macintosh, with p < 0.05 for the participants who reported experience with the videolaryngoscope in the 0-5 and > 15 use categories (Table 1).

Comparison without the useof the aerosol box

When the aerosol box is not used, intubation time drops as compared to when it is used, as shown in Figure 2 and Table 1 (evident when comparing with means and medians). Participants in the third age tercile, first tercile in years of experience as anesthetists, anesthetists,m and those who reported fogging of their goggles, had lower mean values when using the Macintosh vs. the videolaryngoscope, with p < 0.05 (Table 1).

Videolaryngoscope vs. Macintosh comparison during the experimental phase

These analyses were performed based on the first attempt, 17 with videolaryngoscope (group A) and 16 with Macintosh (group B). The groups were set up differently according to position and failed attempts, with p < 0.05. Hazard Ratios do not reflect statistically significant differences, but they show a trend towards lower performance for intubation in participants reporting failed attempts (HR 0.24 [95% CI 0.05-1.03], p = 0.056), while it tends towards faster performance when the Macintosh is used as compared to the videolaryngoscope (HR: 1.36 [95% CI: 0.64-2.88], p = 0.211) (Table 2).

TABLE 2 Videolaryngoscope vs. Macintosh with the use of aerosol box and PPE analysis.

| Characteristic | Total | Videolaryngoscope | Macintosh | p | HR [95% CI] | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (33) | G-A (17) | G-B (16) | 1.36 [0.64-2.88] | 0.211 | ||

| Age | ||||||

| Me (IQR) | 35 (31.5-54) | 33 (30-41) | 38 (32-55) | 0.2121 | 0.98 [0.95-1.01] | 0.276 |

| Years of experience as anesthetist | ||||||

| Me (IQR) | 8.5 (5-25) | 8.5 (5-26) | 12 (4.5-21) | 0.9737 | 0.96 [0.96-1.01] | 0.182 |

| Position % (n) | 0.043 | |||||

| Anesthetist | 72.73 (24) | 64.71 (11) | 81.25 (13) | 1 | ||

| Second-year resident | 15.15 (5) | 29.41 (5) | 0 | 1.39 [0.46-4.14] | 0.550 | |

| Third-year resident | 12.12 (4) | 5.88 (1) | 18.75 (3) | 1.04 [0.30-3.58] | 0.947 | |

| Difficulty % (n) | ||||||

| Goggle fogging | 31.25 (10) | 23.53 (4) | 40.00 (6) | 0.450 | 1.14 [0.50-2.60] | 0.741 |

| Difficulty with laryngoscope | 15.63 (5) | 17.65 (3) | 13.33 (2) | 0.737 | 0.79 [0.29-2.12] | 0.649 |

| Difficulty with aerosol box | 48.48 (16) | 41.18 (7) | 60.00 (9) | 0.288 | 1.04 [0.49-2.21] | 0.902 |

| Special difficulty with the manikin | 3.13 (1) | 0 | 6.67 (1) | 0.469 | 1.02 [0.13-7.68] | 0.983 |

| Difficulty with table height | 30.30 (10) | 23.53 (4) | 37.50 (6) | 0.465 | 0.95 [0.43-2.07] | 0.902 |

| Failed attempts | 15.15 (5) | 29.41 (5) | 0 | 0.044 | 0.24 [0.05-1.03] | 0.056 |

p value: Fisher exact test and Pearson Chi Square test (categorical variables), Mann Whitney U test (numerical variables). HR: Hazard Ratio. 95% CI: 95% confidence interval. Me (IQR): Median (Inter-quartile range).

SOURCE: Authors.

Multiple analysis

After adjusting for years of experience as anesthetist, difficulty with the aerosol box, table height, difficulty with the manikin and with the videolaryngoscope, there is still a trend towards faster intubation with the Macintosh as compared to the videolaryngoscope (HR: 2,20 [95% CI: 0.736.62]).

Participants with more than 8 years of experience who were included in the second and third terciles are identified with an HR lower than 1, which reflects slower speed in performing the procedure, in particular for those in the third tercile; a similar situation was found with the participants who reported difficulties with the aerosol box, the manikin and the videolaryngoscope (Table 3).

TABLE 3 Adjusted Cox regression model for speed in endotracheal intubation in a simulated setting

| Characteristic | HR | [95% CI] | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macintosh group | 2.20 | [0.73-6.62] | 0.159 |

| Anesthetist years of experience | |||

| Tercile 1 (1-6) | 1 | ||

| Tercile 2 (8-20) | 0.59 | [0.16-2.10] | 0.423 |

| Tercile 3 (22-32) | 0.31 | [0.14-1.86] | 0.314 |

| Difficulty | |||

| Difficulty with aerosol box | 0.72 | [0.24-2.18] | 0.571 |

| Difficulty with table height | 1.07 | [0.27-4.11] | 0.920 |

| Difficulty with the manikin | 0.57 | [0.05-6.08] | 0.648 |

| Difficulty with the videolaryngoscope | 0.84 | [0.19-3.59] | 0.818 |

HR: Hazard Ratio. 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

SOURCE: Authors.

Kaplan-Meier crude and adjusted analysis

A review of the time and speed for intubations showed that all the participants who made their first attempt at intubation using the Macintosh laryngoscope accomplished it in less than 40 minutes, while those who were assigned to the videolaryngoscope required up to 58 seconds. The figure created using the adjusted model shows lower intersections between the groups (Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

The aerosol box - with its adaptations 5 - can help improve protection for the healthcare staff performing invasive airway procedures, given its structural characteristics 11,12; however, questions regarding its effectiveness still exist. Although not the objective of this research, it is important to highlight that studies on its effectiveness in enhancing protection for the healthcare staff are performed in negative pressure environments 13, a situation that is not a reality in all clinical settings that are dealing with this pandemic 14. Therefore, notwithstanding withdrawal by the FDA of its recommendation for the use of the aerosol box, there are still questions that must be solved and individual operators must decide according to their perception of safety in each particular situation 15.

The biggest concern among experts in the management of these types of patients is the potential for increasing the time and degree of difficulty of the intubation maneuver 16. This has been expressed in the form expert opinions and letters in various specialized journals. In fact, there is a paucity of studies in the literature delving into this question; in simulated settings, there is research from Begley et al. in Australia 17 and Wakabayashi in Japan 18, with similar designs as the one used in this study, but with some important insights that deserve highlighting.

Average intubation times were longer with the aerosol box, both for the videolaryngoscope and the conventional laryngoscope maneuvers, with significant differences. This result is consistent with the observations in the study by Begley, although they only reported on 36 intubations and did not use the conventional laryngoscope; they also compared two different aerosol box designs, as their main objective. On the other hand, they set the time limit for intubation at 180 seconds, as compared to 60 seconds in this work (apnea time) to designate it as a failed attempt. The study by Wakabayashi found statistically significant differences, although not from the clinical point of view, and it is worth noting that with the McGrath MAC videolaryngoscope, also used in this research, performance during the intubation maneuver improved noticeably. It is important to mention that intubation time was determined in a different way in that study: it was measured from the moment the videolaryngoscope was placed in the mouth, and no personal protective equipment was used, except for gloves. The authors of that study highlight that, unlike other research, they made videos of the different maneuvers, and those videos are available.

The benefit of using videolaryngoscopy over conventional laryngoscopy could not be demonstrated in the study. We think that, to make a difference, training and knowledge of the new devices are still needed in our setting. However, it is worth remembering that the selected scenario was a normal airway; different results would be expected in cases of difficult airways, as is described in the literature. In fact, 17 anesthetists reported being familiar with the use of the McGrath MAC, but this was not reflected in the results, although, for them, the time difference was one second longer with the use of the aerosol box.

There were no significantly different results in terms of attempted intubations; of the six cases considered as failed intubations (time greater than 60 seconds), four happened with the use of the aerosol box, and there is a relationship with the subjective report from 50% of the anesthetists of difficulty handling the box.

We consider that the findings of our research are relevant given the use of rigorous methodology, the number of procedures and the objectivity of the measurements. Residents in their second year of training and beyond, with certified competency of having performed more than 80 successful intubations in their clinical practice were included; it is noteworthy that performance was better in this group of operators, explained by the familiarity among younger generations with the manipulation of simulation equipment, which is part of their academic training.

Given the above, we recognize that a weakness and limitation of our work was the lack of training on the use of simulation and airway equipment among the participants before gathering the sample. Only one trial intubation was allowed with each device without the use of the aerosol box. Moreover, the simulation did not take place in clinical settings and table height or devices could not be modified.

A next step would be to transfer the results to a clinical study, with all the design challenges it entails. So far, we are only aware of a non-inferiority study carried out in Pennsylvania by Madabhushi et al., 19 which considered a safety range of 15 seconds and showed no implications or consequences derived from the use of the modified aerosol box, together with a videolaryngoscope in a controlled setting, as would be the case of anesthesia induction in the operating room, without a difficult airway. Patients with respiratory failure are different and, moreover, it is important to consider protocols, procedures and administration of the medications required according to the event 20.

In conclusion, the use of the aerosol box and personal protective equipment in a simulated setting hinders the maneuver and may prolong intubation time. It does not seem to be reasonable to use the device in uncontrolled settings as is the case of urgent critically ill patients, predicted difficult airway or intubation by people who are not duly trained. Moreover, a tool like the videolaryngoscope is a useful resource for endotracheal intubation, and training must be provided on a continuous basis.

ETHICAL RESPONSIBILITIES

Ethics committee endorsement

This study was endorsed by the institutional Bioethics Committee of Universidad Industrial de Santander, as stated in Minutes 012 of June 02, 2020.

Human and animal protection

The authors declare that no experiments were carried out in humans or animals for this research. The authors declare that all the procedures were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards set forth by the human experimentation committee, the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data confidentiality

The authors declare that they followed the protocols of their institution regarding disclosure of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consent

The authors declare that no patient information appears in this paper and bioethical principles (confidentiality, autonomy, beneficence and non-maleficence) were respected. The authors obtained the informed consent from the patients and/or subjects to which this article refers. The forms are kept by the corresponding author.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors' contributions

SÁR: Conception of the original project as principal investigator in representation of the ANESTIDOC team at UIS, data collection, interpretation of the results and final drafting and approval of the manuscript.

CCTC: Conception of the original project as principal investigator in representation of the Everest group at UDES, study planning, data collection, interpretation of the results, data analysis and final drafting of the manuscript.

RRC: Co-investigator in representation on the Everest group at UDES, study planning, data analysis,final drafting and approval of the manuscript.

VMLA: Conception of the original project as co-investigator of the study in representation of the UIS Anestedoc team, data collection, interpretation of the results and initial drafting of the manuscript.

SMVG: Data collection coordination, support to the interpretation of the results and initial drafting of the manuscript.

text in

text in