Heart failure and type 2 diabetes mellitus represent two of the most relevant non-transmissible chronic diseases worldwide, representing a critical public health issue nowadays 1. An estimated 6.2 million individuals were living with heart failure in the United States between 2013 and 2016, while its prevalence in Latin American countries was 1% [95% confidence interval (95%CI): 0.1%- 2.7%) between 1994 and 2014 2,3. Moreover, approximately 26 million people are affected by heart failure worldwide, representing an estimated health expenditure of around USD $31 billion by 2012, which is expected to increase by 127% by 2030 3. On the other hand, an estimated 462 million individuals have been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus by 2017, reflecting a prevalence rate of 6059 cases per 100,000 population. Moreover, around one million deaths per year can be attributed to diabetes alone, positioning this disease as the ninth leading cause of mortality worldwide 4.

Heart failure and type 2 diabetes mellitus commonly coexist, exponentially increasing the risk of complications in the patients affected by both conditions 5. This coexistence is derived from the common pathophysiological pathways both heart failure and type 2 diabetes mellitus share 1,6. This association was first observed in the Framingham study after more than 40 years of follow-up. In this cohort, men and women with diabetes mellitus had a two- and five-times higher risk of developing heart failure compared to the general population, respectively 7. These findings could partially explain why the prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in heart failure patients is exceptionally high (estimated to be around 30% to 50%) 5. However, a new hypothesis suggesting a bidirectional relation between heart failure and type 2 diabetes mellitus has also been gaining relevance in recent years, giving further explanation to this observed prevalence, and highlighting the importance of type 2 diabetes mellitus and heart failure coexistence 1.

In this context, type 2 diabetes mellitus can modify heart failure’s disease course, increasing the risk of adverse outcomes, including rehospitalizations, prolonged hospital stays, and even mortality, mainly in the context of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction 8,9. Nonetheless, the knowledge of the potential interactions and effect modifications that type 2 diabetes mellitus can elicit on mortality-associated risk factors is still poorly understood 10. Understanding these is crucial for an optimal approach and adequate guiding of the patient’s management to achieve the expected goals 11. The present study aimed to characterize the risk factors for mortality in patients with heart failure and type 2 diabetes mellitus from RECOLFACA and evaluate the potential effect modifications by type 2 diabetes mellitus over other risk factors.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

The RECOLFACA is a prospective cohort study conducted at 60 medical centers, heart failure clinics, and cardiology outpatient centers in Colombia. Patient enrollment started in February 2017 and ended in October 2019. It included all adult patients (older than 18 years) with a clinical diagnosis of heart failure of any etiology based on the guideline recommendations at the time of inclusion, with at least one hospitalization due to heart failure in the 12 months before enrollment. Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria, along with additional methodologic characteristics of the registry, are described elsewhere 12,13.

Data collection

Information regarding sociodemographic, clinical, and laboratory variables was registered at baseline. Type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosis was based on self-report, laboratory test results (fasting glucose level > 125 mg/dl or glycated hemoglobin [HbA1c] of more than 7%), or glucose-lowering therapy use. Heart failure severity was assessed using the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification.

An ischemic disease diagnosis was registered if the patient underwent a coronary revascularization procedure or if a previous myocardial infarction history was present. The following comorbidities were assessed: chronic kidney disease, arterial hypertension, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), thyroid disease, and dyslipidemia. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated with the MDRD formula, and an eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 was considered the cut-off for chronic kidney disease. Available data on additional echocardiographic variables was registered. The left ventricle ejection fraction variable was available from 2041 patients (81.2%), 502 from the type 2 diabetes mellitus group (80.9%) and 1539 from the non-type 2 diabetes mellitus group (81.3%), the systolic diameter of the left ventricle variable was available from 1305 patients (51.9%), 299 from the type 2 diabetes mellitus group (48.2%) and 1006 from the non-type 2 diabetes mellitus group (53.1%), and the valvular pathology variable was available from all patients. We considered triple therapy as the presence of the prescription of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), plus a beta-blocker and a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was all-cause mortality. Data on this outcome was collected using a questionnaire applied by each heart failure clinic and center two times per year. The current results represent the data from the follow-up performed after six months of enrollment into the registry. Each center also reviewed each patient’s clinical records to assess specific data about the outcomes.

Statistical analysis

At first, the total sample was divided into two groups (diabetics vs. nondiabetics). Baseline characteristics were described as medians and quartiles for quantitative variables, or absolute counts, proportions and percentages for categorical variables. Differences between groups were assessed using Pearson’s chi square and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U tests for quantitative variables. The cumulative incidence of the mortality events was calculated with their respective 95% confidence intervals. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method and adjusted Cox proportional hazard models.

A multivariable Cox regression model including all the variables significantly associated with mortality was generated; after this, variables independently associated with this outcome were selected. The final model included all the independent predictors of mortality and was also adjusted by age, sex, chronic kidney disease diagnosis, NYHA classification, and left ventricle ejection fraction. Effect modification was assessed using multiple Cox regression and the Mantel-Haenszel method.

In summary, an effect modifier corresponds to a variable that differentially modifies a risk factor’s observed effect regarding a determined outcome. This results in different risk estimates between the evaluated groups when the effect modifier is present. A p value less than 0.05 (two-tailed test) was considered as statistically significant. All analyses were performed using statistical package Stata™, version 15 (Station College, Texas USA).

Results

From the total 2528 patients included in RECOLFACA between February 2017 and October 2019, 2514 patients had information regarding type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosis. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus among these patients was 24.6% (n = 620).

Baseline characteristics

No significant demographic differences were observed between the groups regarding sex, age, and ethnicity (table 1). However, patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosis had a significantly higher prevalence of hypertension, coronary disease, valvular disease, chronic kidney disease, and dyslipidemia. On the other hand, non-diabetic individuals had more frequently a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation, valvular disease, and Chagas’ disease (table 1). Regarding the pharmacological therapy, patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosis were more frequently prescribed angiotensin receptor blockers, antiplatelets, and statins, while non-diabetics reported higher use of MRA, ACEI, and digoxin. Finally, diabetic patients showed a lower value of hemoglobin,and glomerular filtration rate while having a higher prevalence of electrolytic disorders.

Table 1 Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients with heart failure diagnosis enrolled in the Registro Colombiano de Insuficiencia Cardíaca (RECOLFACA) by type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosis

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus (N = 2514) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 1894) n (%) | Yes (n = 620) n (%) | Total n (%) | p value | ||

| Sex | 0.195 | ||||

| Female | 790 (41.7) | 277 (44.7) | 1067 (42.4) | ||

| Male | 1104 (58.3) | 343 (55.3) | 1447 (57.6) | ||

| Age (years) | 69 (59.78) | 69 (62.77) | 69 (59.78) | 0.443 | |

| Race | 0.400 | ||||

| Asian | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.0) | ||

| White | 85 (4.5) | 31 (5.0) | 116 (4.6) | ||

| Indigenous | 9 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 10 (0.4) | ||

| Hispanic | 1398 (73.8) | 455 (73.4) | 1853 (73.7) | ||

| Mestizo | 342 (18.1) | 116 (18.7) | 458 (18.2) | ||

| African-American | 60 (3.2) | 16 (2.6) | 76 (3.0) | ||

| Hypertension | 1283 (67.7) | 528 (85.2) | 1811 (72.0) | < 0.001 | |

| Alcoholism | 69 (3.6) | 17 (2.7) | 86 (3.4) | 0.284 | |

| Cancer | 75 (4.0) | 26 (4.2) | 101 (4.0) | 0.797 | |

| Depression | 34 (1.8) | 13 (2.1) | 47 (1.9) | 0.630 | |

| Dementia | 17 (0.9) | 5 (0.8) | 22 (0.9) | 0.833 | |

| Coronary disease | 482 (25.4) | 224 (36.1) | 706 (28.1) | < 0.001 | |

| COPD | 328 (17.3) | 113 (18.2) | 441 (17.5) | 0.606 | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 456 (24.1) | 104 (16.8) | 560 (22.3) | < 0.001 | |

| Thyroid disease | 279 (14.7) | 109 (17.6) | 388 (15.4) | 0.088 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 257 (13.6) | 177 (28.5) | 434 (17.3) | < 0.001 | |

| Valvular disease | 342 (18.1) | 87 (14.0) | 429 (17.1) | 0.021 | |

| Smoking habits (former or current) | 341 (18) | 112 (18.1) | 453 (18) | 0.836 | |

| CABG | 109 (5.8) | 61 (9.8) | 170 (6.8) | < 0.001 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 427 (22.5) | 220 (35.5) | 647 (25.7) | < 0.001 | |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 475 (25.1) | 218 (35.2) | 693 (27.6) | < 0.001 | |

| Chagas’ disease | 76 (4.0) | 12 (1.9) | 88 (3.5) | 0.015 | |

| NYHA | 0.094 | ||||

| I | 241 (12.7) | 57 (9.2) | 298 (11.9) | ||

| II | 998 (52.7) | 352 (56.8) | 1350 (53.7) | ||

| III | 565 (29.8) | 182 (29.4) | 747 (29.7) | ||

| IV | 90 (4.8) | 29 (4.7) | 119 (4.7) | ||

| ACC/AHA classification | |||||

| C | 1792 (94.6) | 585 (94.4) | 2377 (94.6) | 0.805 | |

| D | 102 (5.4) | 35 (5.7) | 137 (5.5) | ||

| ACEI | 674 (35.6) | 172 (27.7) | 846 33.7) | < 0.001 | |

| ARB | 766 (40.4) | 303 (48.9) | 1069 (42.5) | < 0.001 | |

| Diuretics | 1257 (66.4) | 436 (70.3) | 1693 (67.3) | 0.068 | |

| Beta-blockers | 1639 (86.5) | 550 (88.7) | 2189 (87.1) | 0.162 | |

| ARNI | 176 (9.3) | 69 (11.1) | 245 (9.7) | 0.181 | |

| MRA | 1082 (57.1) | 317 (51.1) | 1399 (55.6) | 0.009 | |

| Ivabradine | 111 (5.9) | 39 (6.3) | 150 (5.9) | 0.790 | |

| Digoxin | 206 (10.9) | 45 (7.3) | 251 (10.0) | 0.009 | |

| Nitrates | 62 (3.3) | 29 (4.7) | 91 (3.6) | 0.104 | |

| Antiagregants | 804 (42.4) | 356 (57.4) | 1160 (46.1) | < 0.001 | |

| Statins | 984 (52.0) | 407 (65.6) | 1391 (55.3) | < 0.001 | |

| Anticoagulants | 506 (26.7) | 137 (22.1) | 643 (25.6) | 0.022 | |

| Pacemaker | 0.975 | ||||

| Dual-chamber | 73 (3.9) | 25 (4.0) | 98 (3.9) | ||

| Single-chamber | 37 (2.0) | 12 (1.9) | 49 (2.0) | ||

| Other implantable devices | 0.826 | ||||

| ICD | 286 (15.1) | 84 (13.6) | 370 (14.7) | ||

| Resynchronization therapy | 35 (1.8) | 13 (2.1) | 48 (1.9) | ||

| ICD + resynchronization therapy | 98 (5.2) | 29 (4.7) | 127 (5.1) | ||

| Sinus rhythm | 636 (33.6) | 231 (37.3) | 867 (34.5) | 0.094 | |

| QRS complex | |||||

| < 120 ms | 633 (33.4) | 200 (32.3) | 833 (33.1) | 0.785 | |

| > 120 ms | 42 (2.2) | 17 (2.7) | 59 (2.3) | ||

| LV diastolic diameter | 57 (48-65) | 55 (48-63) | 57 (48-65) | 0.045 | |

| LVEF | 32 (25-42) | 33 (25-42) | 33 (25-42) | 0.645 | |

| Hemoglobin (mg/dl) | 13 (12.14) | 12 (11.14) | 13 (12.14) | < 0,001 | |

| Anemia | 494 (35.4) | 232 (48.3) | 726 (38.7) | < 0,001 | |

| Serum creatinine | 1.1 (0.9-1.35) | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) | < 0,001 | |

| GFR (ml/min/1,73 m3) | 59 (44.78) | 53 (36.74) | 57 (43.77) | < 0,001 | |

| Hyponatremia | 1079 (56.9) | 390 (62.9) | 240 (9.5) | < 0,001 | |

| Hyperkalemia | 113 (8.3) | 63 (12.6) | 176 (9.4) | 0,005 | |

| NT-proBNP | 2151 (855-5089) | 2795 (1002-6857) | 2255 (950-5594) | 0,101 | |

COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting; NYHA: New York Heart Association; ACC/AHA: American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association; ACEI: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB: Angiotensin receptor blockers; ARNI: Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor; MRA: Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; ICD: Implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LV: Left ventricle; LVEF: Left ventricular ejection fraction; GFR: Glomerular filtration rate; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide

Mortality and associated factors

The median follow-up time was 215 days (Q1: 188; Q3: 254). A total of 170 patients (6.76%) died during the follow-up, for a mortality rate of 0.29 per 1,000 person-years (95% CI: 25.4-34.5). Significantly higher mortality was observed in the type 2 diabetes mellitus group than in the non-diabetic group (8.9% vs. 6.1%, respectively; p = 0.016). Supplementary table 1 summarizes the association between the evaluated variables and mortality use a bivariate analysis. From these variables, we included those that were significantly associated with mortality in the multivariable Cox regression model. Finally, after adjusting by age, sex, type 2 diabetes mellitus, bchronic kidney disease, NYHA classification, and left ventricle ejection fraction, seven independent predictors of short-term mortality were identified (table 2).

Table 2 Factors independently associated with short-term mortality in the current cohort of heart failure patients. The logistic regression model was also adjusted by age, sex, chronic kidney disease, New York Heart Association classification, and left ventricular ejection fraction.

| Factor | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| COPD | 1.76 (1.03-3.02) | 0.039 |

| Sinus rhythm | 0.56 (0.34-0.92) | 0.022 |

| Triple therapy | 0.41 (0.23-0.73) | 0.003 |

| Nitrates use | 3.01 (1.19-7.63) | 0.020 |

| Statins use | 0.48 (0.28-0.80) | 0.005 |

| Anemia | 1.85 (1.12-3.04) | 0.016 |

| Hyperkalemia | 3.09 (1.64-5.83) | 0.001 |

CI: Confidence interval; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Furthermore, we also analyzed the variables associated with mortality in the type 2 diabetes mellitus subgroup (table 3). In this specific sub-group, only chronic kidney disease, smoking status, statins use, anticoagulants use, left ventricle diastolic diameter, and anemia were significantly associated with the mortality outcome, being some of these factors different from those observed in the general cohort. The multivariate analysis showed that only the left ventricle diastolic diameter was an independent mortality predictor in the type 2 diabetes mellitus group (HR = 0.96; 95% CI: 0.93-0.98).

Table 3 A bivariate analysis evaluating the association between the sociodemographic and clinical variables with short-term all-cause mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosis of the Registro Colombiano de Insuficiencia Cardíaca (RECOLFACA)

| Alive (n = 565) n (%) | Dead (n =55) n (%) | Total (N = 620) n (%) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 250 (44.25) | 27 (49.09) | 277 (44.68) | 0.490 | |

| Male | 315 (55.75) | 28 (50.91) | 343 (55.32) | ||

| Age (years) | 69 (62.77) | 69 (63.79) | 69 (62.77) | 0.453 | |

| Race | |||||

| Asian | 1 (0.18) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.16) | ||

| White | 29 (5.13) | 2 (3.64) | 31 (5) | ||

| Indigenous | 1 (0.18) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.16) | 0.167 | |

| Hispanic | 420 (74.34) | 35 (63.64) | 455 (73.39) | ||

| Mestiza | 102 (18.05) | 14 (25.45) | 116 (18.71) | ||

| African-American | 12 (2.12) | 4 (7.27) | 16 (2.58) | ||

| Hypertension | 478 (84.60) | 50 (90.91) | 528 (85.16) | 0.209 | |

| Current alcoholism | 14 (2.48) | 3 (5.45) | 17 (2.74) | 0.197 | |

| Cancer | 21 (3.72) | 5 (9.09) | 26 (4.19) | 0.058 | |

| Coronary disease | 200 (35.40) | 24 (43.64) | 224 (36.13) | 0.225 | |

| COPD | 99 (17.52) | 14 (25.45) | 113 (18.23) | 0.146 | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 92 (16.28) | 12 (21.82) | 104 (16.77) | 0.294 | |

| Thyroid disease | 96 (16.99) | 13 (23.64) | 109 (17.58) | 0.216 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 153 (27.08) | 24 (43.64) | 177 (28.55) | 0.009 | |

| Valvular disease | 80 (14.16) | 7 (12.73) | 87 (14.03) | 0.770 | |

| Smoking habits (former or current) | 96 (16.99) | 16 (29.09) | 112 (18.06) | 0.026 | |

| CABG | 57 (10.09) | 4 (7.27) | 61 (9.84) | 0.503 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 206 (36.46) | 14 (25.45) | 220 (35.48) | 0.103 | |

| Chagas disease | 11 (1.95) | 1 (1.82) | 12 (1.94) | 0.947 | |

| NYHA | |||||

| I | 54 (9.56) | 3 (5.45) | 57 (9.19) | ||

| II | 325 (57.52) | 27 (49.09) | 352 (56.77) | 0.167 | |

| III | 162 (28.67) | 20 (36.36) | 182 (29.35) | ||

| IV | 24 (4.25) | 5 (9.09) | 29 (4.68) | ||

| ACC/AHA classification | |||||

| C | 533 (94.34) | 52 (94.55) | 585 (94.35) | 0.949 | |

| D | 32 (5.66) | 3 (5.45) | 35 (5.65) | ||

| Triple therapy | 242 (42.83) | 24 (43.64) | 266 (42.90) | 0.908 | |

| Diuretics | 391 (69.20) | 45 (81.82) | 436 (70.32) | 0.051 | |

| Digoxin | 40 (7.08) | 5 (9.09) | 45 (7.26) | 0.583 | |

| Nitrates | 24 (4.25) | 5 (9.09) | 29 (4.68) | 0.104 | |

| Antiplatelet | 328 (58.05) | 28 (50.91) | 356 (57.42) | 0.306 | |

| Statins | 380 (67.26) | 27 (49.09) | 407 (65.65) | 0.007 | |

| Anticoagulants | 117 (20.71) | 20 (36.36) | 137 (22.10) | 0.008 | |

| Pacemaker | 0.054 | ||||

| Dual-chamber | 24 (4.25) | 1 (1.81) | 25 (4.42) | ||

| Single-chamber | 9 (1.59) | 3 (5.45) | 12 (2.12) | ||

| Other implantable devices | 0.181 | ||||

| ICD | 94 (16.64) | 12 (21.82) | 106 (17.10) | ||

| Resynchronization therapy | 10 (1.77) | 3 (5.45) | 13 (2.10) | ||

| ICD + resynchronization therapy | 27 (4.78) | 2 (3.62) | 29 (4.68) | ||

| Sinusal rhythm | 213 (68.93) | 18 (72) | 231 (69.16) | 0.749 | |

| Prolonged QRS complex | 126 (40.78) | 8 (32) | 134 (40.12) | 0.389 | |

| LV diastolic diameter | 55 (48.63) | 50.5 (3958) | 55 (4863) | 0.015 | |

| LVEF | 34 (25.43) | 28 (2040) | 33 (2542) | 0.101 | |

| Anemia | 212 (48.51) | 20 (46.51) | 232 (48.33) | 0.007 | |

| Serum creatinine | 1.2 (0.93-1.60) | 1.29 (1.1.8) | 1.2 (0.95-1.61) | 0.409 | |

| GFR (ml/min/1,73 m3) | 53.35 (36.05-75.24) | 52.37 (33.05-66.58) | 53.3 (35.71-74.21) | 0.521 | |

| Hyponatremia | 61 (14.59) | 9 (21.43) | 70 (15.22) | 0.240 | |

| Hyperkalemia | 54 (11.82) | 9 (20.45) | 63 (12.57) | 0.099 | |

| NT-proBNP | 2790 (1099-5896) | 9496 (996- 1671) | 2795 (1002-6857) | 0.254 |

COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting; NYHA: New York Heart Association; ACC/AHA: American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association; ACEI: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB: Angiotensin receptor blockers; ARNI: Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin Inhibitor; MRA: Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; ICD: Implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LV: Left ventricle; LVEF: Left ventricular ejection fraction; GFR: Glomerular filtration rate; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide

Interaction and effect modification by diabetes mellitus

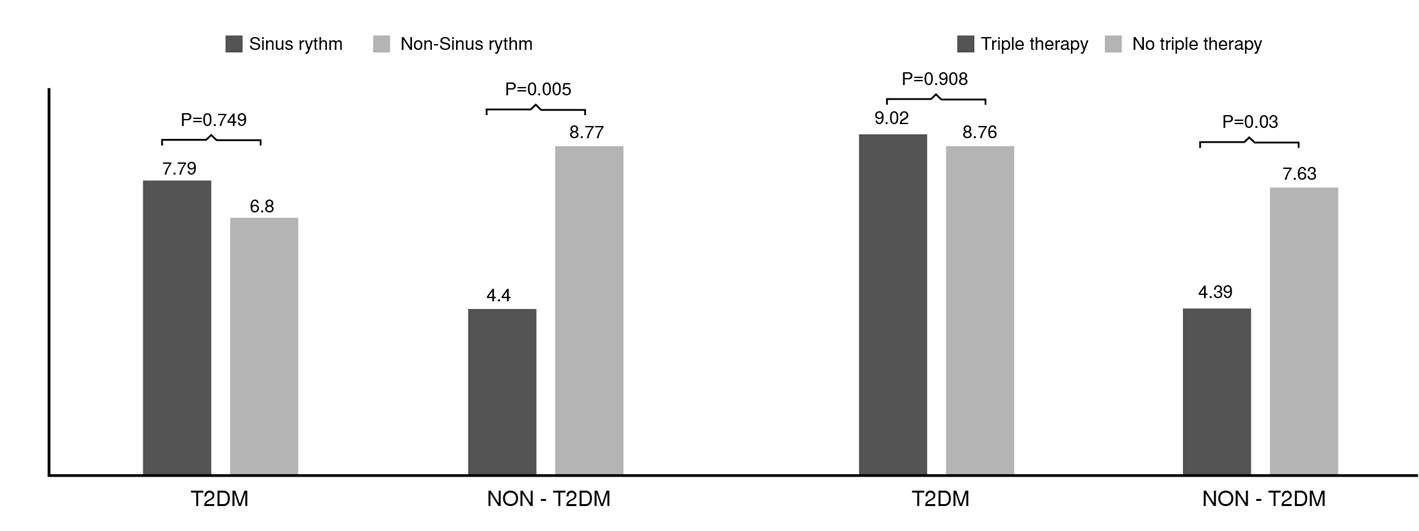

There were relevant differences when assessing the independent factors by the type 2 diabetes mellitus group. At first, patients receiving triple medical therapy in the non-type 2 diabetes mellitus group had significantly lower mortality than those not receiving this therapeutic scheme.

On the other hand, the incidence of mortality was not statistically different in the group of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (figure 1). A similar result was observed regarding the report of sinus rhythm in the last electrocardiogram performed. No additional significant differences were observed for the other independent predictor variables.

Figure 1 Mortality in patients according to sinus rhythm and triple therapy [angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI)/angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), beta-blocker and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA)] by type 2 diabetes mellitus group.

Despite these findings, there was no evidence of effect modification by type 2 diabetes mellitus on the relationship between any of the independent predictors and all-cause mortality (figure 2). Furthermore, no interaction terms by type 2 diabetes mellitus were observed in the assessed sample (figure 2). Nevertheless, an interesting result was observed when assessing smoking history. Although it was not an independent predictor of short-term mortality in the general cohort, patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and tobacco consumption (current or former) had a significantly higher risk of mortality (HR = 1.84; 95% CI: 1.01-3.35) while the difference was not statistically significant in non-diabetic individuals (HR = 0.61; 95% CI: 0.35-1.11). Moreover, a significant effect modification by type 2 diabetes mellitus on the association between tobacco consumption and mortality was observed (p value = 0.005), along with a significant interaction term between both variables (p value for interaction = 0.010).

Discussion

In the present study, the differential characteristics of patients with heart failure with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus enrolled in the RECOLFACA were described. Almost one-fourth of the patients with heart failure from the registry had a concomitant diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus, highlighting a lower use of MRA, ACEI, and digoxin in these patients, along with a higher prevalence of chronic kidney disease, anemia, and electrolytic disorders. Finally, type 2 diabetes mellitus had a higher risk of mortality in the univariate analysis. Only COPD, nitrate use, anemia, and hyperkalemia were independently associated with higher mortality risk in the general cohort. In contrast, sinus rhythm, triple therapy with ACEI/ARB, MRA and beta-blockers, and statin use were associated with a lower risk of this outcome. Regarding the type 2 diabetes mellitus group, only left ventricle diastolic diameter was independently associated with mortality.

Finally, in our registry, type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosis did not modify the effect of independent predictors of all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure after adjusting by relevant sociodemographic and clinical variables. Likewise, several studies have evaluated the potential effect modification that type 2 diabetes mellitus could exert in different contexts, but only some of those performed in cardiovascular disease settings have reported that type 2 diabetes mellitus does not modify mortality risk when several risk factors are present 10,14,15. The study by Selvarajah et al.10, which evaluated patients with cardiovascular disease, observed that type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosis did not modify the effect of renal impairment with all-cause mortality after a follow-up of 33.198 person-years. Similarly, Gerstein et al.14 observed that microalbuminuria was an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality both in patients with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosis. On the other hand, Ahmed et al.15 reported that type 2 diabetes mellitus modified the effect of eGFR regarding all-cause mortality risk; however, their analysis was not adjusted by albuminuria, which precluded a more precise assessment due to the impact of albuminuria in the risk of mortality.

In regard to the higher mortality found in the type 2 diabetes mellitus group when compared to non-diabetics, our results coincide with those reported in the meta-analysis performed by Dauriz et al.16, where they found approximately 30% increased risk of all-cause death. Moreover, they reported that nearly one-quarter of the patients with heart failure had diabetes, similar to what we reported in the RECOLFACA. The AMERICCAASS is a recent registry that also included heart failure patients older than 18 years, that reported a similar finding of 28% patients with heart failure and diabetes in their results from the first 1,000 patients enrolled from different Latin American countries, including Colombia 17. Another large registry that analyzed data from more than 45,000 patients from different continents, including Latin America, was the Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) registry, where approximately 30% of increased mortality in diabetic group vs. non-diabetics was also found. However, the inclusion criteria of the REACH registry are different from ours as they not only included patients older than 18 years with heart failure, but all patients > 45 years old that had established atherosclerosis or ≥ 3 risk factors for atherosclerosis, hence, the results are not comparable to ours.

In our study patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and tobacco consumption had a significantly higher risk of mortality. A related finding was reported by the study of Jeong et al.18 where they analyzed data from 349,137 type 2 diabetes mellitus Korean patients with current or history of smoking. In their study they reported that smoking cessation was associated with a 10% lower risk of all-cause mortality. However, contrary to our study, the population they studied did not have heart failure as a baseline condition, hence, our results are not completely comparable. This could suggest that the higher risk of mortality seen between patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and tobacco consumption (current or former), has no direct relation to the heart failure diagnosis they had.

Our results regarding the variables that are independently associated with higher mortality risk in the general cohort coincide with previous reports. Although few studies have analyzed the prognosis of patients with heart failure and COPD, it has been reported as an independent predictor of death and heart failure hospitalization when reported in multivariable models 19. Only one study has explored the causes of increased mortality 20.

According to a study with 4606 acute care patients with congestive heart failure, the use nitrates is associated with increased relative risk of in-hospital mortality 21. Anemia has been found as an independent predictor by multiple studies, including the study by Gupta et al.22 where they found that anemia emerged as an independent predictor of all-cause mortality and heart failure hospitalizations at the end of the follow-up, and the recent study by Köseoğlu et al.23 who found similar results. Lastly, hyperkalemia is a known risk factor for mortality among critically ill patients and cardiac patients 24.

The systematic review of Girerd et al.25 showed that the benefits of heart failure treatment appear to be similar in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus as in non-diabetic patients, suggesting a lack of effect modification by this condition.

However, Kroon et al.26 assessed the potential effect modification by type 2 diabetes mellitus in the association between B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and changes in left ventricular function markers in patients with incipient heart failure. In this study, type 2 diabetes mellitus modified BNP’s effect over left ventricular mass index, left atrial volume * left ventricular mass index, and E/e’ ratio, even after adjustment by sex, age, baseline left ventricular mass index, body mass index, and use of antihypertensives.

Finally, Ebong et al.27 reported that type 2 diabetes mellitus, independently of its treatment and severity, modified the effect of the association between lipid fractions and incident heart failure, potentially due to the pathophysiological process of glucolipotoxicity. Although in our study type 2 diabetes mellitus was identified as a significant effect modifier of the impact of smoking habits and mortality, there are no previous reports on this specific topic. However, it is worth mentioning that cigarette smoking has been identified as a contributor to all-cause mortality the general population, which is expected to be similar in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients 28. Moreover, among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients, cigarette smoking may accelerate cardiovascular disease mortality 29,30.

Regarding treatment, for several years, there were concerns about the use of beta-blockers in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus due to the perceived risk of hypoglycemia, limiting their use in patients with heart failure and type 2 diabetes mellitus despite the benefit observed in heart failure trials 25,31. Furthermore, several clinical trials have reported that the impact of heart failure medical therapy on prospective outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus could be significantly different from the one observed in non-diabetic patients 32. Unfortunately, some of these trials were performed in the 80s and 90s; thus, these studies did not assess interactions and effect modifications.

A recent post-hoc analyses and meta-analyses have suggested that the efficacy of the therapy with ACEI/ARB, MRA, and beta-blockers is similar in heart failure patients with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus, observations that are consistent with the results of the present study 33-36. These findings’ relevance lies in the possibility of promoting an optimal medical treatment for patients with heart failure despite being diabetic or not 37. To achieve this goal, non-cardiologists who treat patients with heart failure and type 2 diabetes mellitus should be invited to actively participate in the therapeutic optimization process and patient referral to specialized centers for interventional strategies. The involvement of nurses, general practitioners, internal medicine specialists, endocrinologists, and diabetologists in the process of up-titration of heart failure medications has been shown to be safe and efficient in achieving target doses of ACEI/ARB, MRA, and beta-blockers 36-38.

Finally, our findings showed that several comorbidities and clinical conditions were independently associated with a higher risk of short-term mortality in heart failure patients, which is consistent with the literature 39-42. The effect of these conditions on short term mortality risk was not modified by type 2 diabetes mellitus; nonetheless, we observed a significant effect modification by type 2 diabetes mellitus in the association between smoking status and mortality. This finding may derive from the common pathophysiological processes that both type 2 diabetes mellitus and smoking promote, which results in a higher incidence of macrovascular and microvascular complications due to a synergistic negative effect of these two conditions combined 43,44.

Limitations of the study

The present study had from several limitations. The RECOLFACA does not collect information regarding HbA1C levels or antidiabetic treatment; therefore, adjustment by these important variables was not possible. Moreover, no information was available on the duration and severity of type 2 diabetes mellitus, including organ involvement. In addition, only a short follow-up was available for the analyses, therefore limiting the precision of the calculated estimates. Lack of power could have been an issue in the present study, potentially leading to false non-significance when the interaction terms and effect modifications were assessed. Moreover, several potential sources of variation were not accounted for in the present study such as body mass index or other relevant diagnoses like asthma. Finally, it was not possible to have data from all patients regarding echocardiographic variables which could be a confounding factor. Therefore, our results should be interpreted with caution.

RECOLFACA is the largest multicentric registry from Colombian patients with heart failure. In this registry, patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus were less frequently treated with MRA, ACEI, and digoxin than non-diabetics while having a higher mortality rate. Moreover, several clinical conditions were independently associated with mortality in this registry. Our results also suggest that type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosis does not modify the effect of the independent risk factors for mortality in heart failure evaluated. However, type 2 diabetes mellitus was observed to significantly modify the risk relation between mortality and smoking in patients with heart failure.

Competency in patient care and procedural skills: patients with heart failure and type 2 diabetes mellitus in Colombia are less frequently treated with important heart failure drugs compared to non-diabetics, highlighting the need of optimizing the pharmacological therapy in this population. Finally, although type 2 diabetes mellitus did not modify the effect of mortality risk factors in heart failure, it seems it can elicit a relevant effect modification in the relationship between smoking history and mortality.

Translational outlook: Further research is needed to assess the role of tipe 2 diabetes mellitus as an effect modifier for risk factors of all-cause mortality in heart failure patients.