Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is characterized by symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. It is considered a public health problem due to its high prevalence and impact on the different spheres of the people suffering from it 12. The approximate prevalence worldwide is 5% in children and 2.5% in adults 3.

A literature review about the prevalence of ADHD in children and adolescents revealed that European countries such as Spain report a prevalence of 11.52% among children aged 6 to 11 years 4-5, while England shows a rate of 8% in 10-year-olds 6. Norway records a prevalence of 5.2% in children aged 7 to 9 years 7. In Asia, ADHD prevalence is higher in Japan, with a prevalence of 31% in children aged 3-6 years 8, while in China the prevalence is 4.6% among those aged 5-15 years 9. In Africa, the Republic of Congo has a prevalence of 6% in children aged 7-9 years 10 and in Nigeria the prevalence is 6.6% in those aged 6-8 years 11.

Latin America presents the greatest variability and the highest prevalence figures, with ranges between 5 and 20% According to the Latin American League for the Study of ADHD 13, there are 36 million people in Latin America affected with ADHD, with less than a quarter receiving multimodal treatment. In Panama, the prevalence is 7.4% among those aged 6-11, years 4-14. Brazil reports a rate of 13% in population aged 6-12 years 15, while Mexico shows a prevalence of 14.6% 16. In the case of Colombia, the ADHD prevalence reaches up to 20%, being the highest in Latin America 17.

Table 1 presents the compiled ADHD prevalence data from various studies.

Table 1 Prevalence of ADHD in different countries

| Countries | Prevalence | Population |

|---|---|---|

| Spain (4-5) | 11.52% | 6 to 11 years |

| England (6) | 8% | 10 years |

| Norway (7) | 5.2% | 7 to 9 years |

| Japan (8) | 31% | 3 to 6 years |

| China (9) | 4.6% | 5 to 15 years |

| Republic of Congo (10) | 6% | 7 to 9 years |

| Nigeria (11) | 6.6% | 6 to 8 years |

| Panama (4-14) | 7.4% | 6 to 11 years |

| Brazil (15) | 13% | 6 to 12 years |

| Mexico (16) | 14.6%% | Children |

| Colombia (17) | Up to 16% | Children |

| France (19) | 7.3% | Adults |

| United States & Holland (19) | 5% | Adults |

| Colombia & Mexico (19) | 1.9% | Adults |

Source: The authors.

Regarding the prevalence of ADHD in adults, a multi-country study covering Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, and the United States aimed to assess the prevalence of mental disorders. The study showed an overall prevalence for ADHD in adults of 3.4%, with the highest rates in France, with 7.3%, and the United States and Holland with 5%; unlike the aforementioned study, Colombia had the lowest prevalence of 1.9%, just as Mexico 18. Although the prevalence of ADHD in adults is low compared to that of children and adolescents, it still represents one of the most frequent psychiatric disorders, on top of schizophrenia (1%) and bipolar disorder (1.5%) 19.

Between 50% and 60% of children who present the disorder in childhood will continue to present it in adulthood 20. This leads to the conclusion that the diagnosis of ADHD is often underdiagnosed in adulthood, and therefore the prevalence rates found are lower than those reported in children and adolescents. This occurs because the diagnostic criteria are pointed at children and are not as sensitive nor flexible enough to assess changes during their development 21.

Studies on the possible causes of ADHD suggest it is due to a combination of several factors. In terms of genetics, studies with family members have shown that there is between 5 to 10 times more risk of presenting the disorder when there are first-degree relatives with ADHD 22-23. Studies with twins estimated a heritability percentage between 70% and 80% 24.

Environmental factors such as prenatal exposure to alcohol, smoking, and illicit drugs have been associated with an increased risk of ADHD 25-26. In addition, perinatal factors such as health complications after birth, fetal distress (hypoxia, forceps delivery), eclampsia, prolonged labor, and low birth weight are part of the background of children with this disorder 27. However, only a small part of the etiology of ADHD can be explained by environmental, perinatal, and psychosocial factors 28. Still, these factors might have an influence, especially in the evolution of the disorder 22-27.

The clinical description of these symptoms in children can be found in medical texts for over 200 years, and even since 1798 some historical references point to the previous observation of behaviors that could be compatible with the disorder 29. Approximately 50 years ago the first publications on ADHD in adults were made, and even more recently, research began to explore the relationship between ADHD and executive functions.

Because the characteristic symptoms of the disorder may be reduced or modified in adulthood, studies show that hyperactive behavior in adults may be directed towards sports activities or occupations that require great activity 30, it also may be reflected in excessive speech, noises in inappropriate situations and/or as a subjective feeling of restlessness or internal uneasiness 31. Symptoms of inattention include low concentration at work, a tendency to forget, not following instructions, not completing tasks, losing objects, neglecting daily activities, or getting upset when performing tasks of sustained mental effort 20. Impulsivity in adults manifests itself as poor frustration tolerance, easy loss of control or impatience 32, difficulty waiting one's turn, interrupting, or intruding in other people's conversations, and getting involved in potentially dangerous activities 20.

There have been several studies that point out the differences between adults with ADHD and the general population. Adults with ADHD are twice as likely to be involved in traffic accidents, and these tend to be more serious 33; they are also more likely to be arrested (39% vs. 20%); they have up to 20% more problems with drug abuse or dependence compared to adults without ADHD 34; they present greater difficulties in maintaining couple and interpersonal relationships 35, have a lower annual income, more dependence on public aid and an increased risk of poverty 36. The risk behaviors previously presented are due to the deficit in executive functions presented by people with ADHD 37.

In addition, 67% of subjects with ADHD have at least one psychiatric comorbidity 38. Because comorbidities are diverse and recurrent in adults, it is common that they mask the primary picture, leading the clinicians to focus more on treating the comorbidities than the ADHD. This would explain how of 4.4% of adults who may have ADHD, only 1.4% are diagnosed 39. Among the most frequent comorbidities in adults with ADHD are drug dependence (19%), affective disorders such as major depression (28%), antisocial personality disorder (23%), and anxiety disorders (10 or 15%) 21. Between 32-53% of adults diagnosed with ADHD have a comorbid alcohol use disorder 40.

On the other hand, executive functions (EF) are defined as high-order skills involved in the generation, regulation, effective execution, and readjustment of goal-directed behaviors 41. These EFs are divided into "cool" and "hot" EFs, the former depends on the dorsolateral prefrontal areas and group cognitive processes, whereas hot EFs are associated with the ventromedial prefrontal area and involve emotional and motivational processes 42. Difficulties in working memory, initiative, planning, order, and monitoring (cool EFs) are a priority in the inattentive subtype, and difficulties in inhibition, change, and emotional control (hot EFs) would be characteristic of the hyperactive/ impulsive subtype 37.

Although there is a clear association between ADHD and deficits in EF in childhood, studies in adults present variable data on this relationship. A systematic review found subtle compromises in measures of EF, low speed of processing complex information, attention deficits, and auditory-verbal learning deficits 43. This low relationship found in different studies can be attributed to different causes: the low sensitivity of tests to assess EF, the existence of different subtypes of ADHD, and even the possibility that there are patients with ADHD without difficulties in EF 44. Other authors argue that EF deficits in ADHD have been associated with the presence of comorbidity and not with the disorder itself 45.

Considering the impact on the quality of life of people with ADHD, it is important to increase the knowledge of executive dysfunctions in adults with ADHD to establish neuropsychological profiles and to enable the development of more effective interventions. Based on the above considerations, the aim of the research was to systematically review studies on executive functioning in adults with ADHD published over the last decade. The objective was to analyze the relationship between these variables and provide an integrative view to the area of neuropsychology.

Methodology

This study is framed within document analysis, specifically as a systematic review, which is an observational and retrospective research that synthesizes the results of multiple primary research on a specific topic 46.

Unit of Analysis

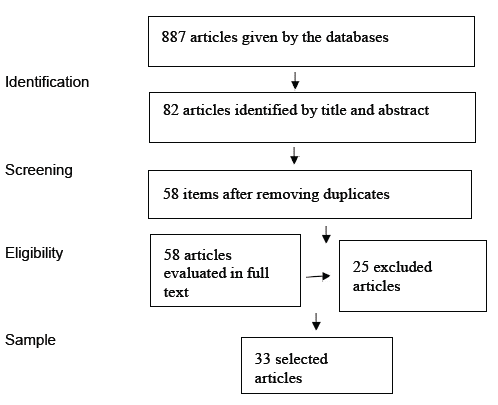

Scientific research articles published from January 2010 to October 2020 that evaluate executive functioning in adults diagnosed with ADHD were considered. This time period was chosen because an increase in the number of annual publications on the topic since 2010 was observed. The unit of analysis consists of 33 articles that meet the inclusion criteria established in the procedure. This sample was extracted from 887 documents retrieved from Pub-Med, Web of Science and EBSCO platforms. Platforms such as Springer, Taylor & Francis, Science Direct and Nature were initially included, but discarded later on because they had less than 3 articles that met the inclusion criteria, or these were already included in any of the 3 selected platforms.

Procedure

Phase I Planning: The research topic was selected and delimited. Subsequently, through a preliminary search for information, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined to select the relevant documents for the study, these were:

- Scientific articles published between 2010 and 2020 in full text. There were no restrictions by country or language, all were included.

- To assess executive functions in adults aged 18 to 60 years diagnosed with ADHD.

- To make use of validated tests for the assessment of executive functioning.

- To have at least 50 people in the study for the results to be meaningful.

Phase II Data collection: The search was carried out from October 12 to 25, 2020, using the PubMed, Web of Science and EBSCO platforms, including all their associated databases. The keywords that were chosen after trying different combinations were: "ADHD", "adults", and "executive functions", without a applying a Boolean search. This search combination was selected as it gave the greatest number of articles that could meet the inclusion criteria. Articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria and studies with inconclusive results were excluded.

Phase III Organization, analysis, and interpretation: For the selection of the studies, all the abstracts of the articles were read and those that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded (Figure 1). Then, a detailed reading of the methodology, results, discussion, and conclusions was made to choose those studies that would be included. In the end, the sample consisted of 33 articles, 22 were extracted from PubMed, 9 from Web of Science, and 4 from EBSCO. For the organization of the information, an Excel database was created with the descriptive and relevant data of each article. Finally, an analysis of the selected studies was carried out, considering the years and countries of publication, diagnostic criteria for ADHD in adults, participants, comorbidities, subtypes, medication, instruments used, dimensions of executive functions assessed, and results.

Phase IV Presentation of results: Preparation of the document presenting the results found after the review and analysis of the studies.

Results

Based on the matrix developed, the categories mentioned in the methodology were analyzed. Table 2 presents the general characteristics of each study. Table 3 contains the main measures and sources considered by the studies to diagnose adults with ADHD, which should be collected in at least 4 articles. Table 4 shows the significant differences in the EFs of ADHD patients. Finally, Table 5 provides a detailed description of the most commonly used instruments to assess executive functions. Instruments used in at least 3 articles for this purpose were considered.

To present the EF findings of the articles, the information was organized, taking into consideration the results of the ADHD group with one of comparison, normal control, control group with other psychiatric disorders, ADHD with medication use, and ADHD with different characteristics. The last column showcases the only two studies that evaluated only one ADHD group, these results show whether they found alterations in EF regarding what was expected by each test used.

The EF processes that were considered for the analysis of the results were chosen because of their frequency of evaluation in at least 3 articles. The main measures and sources that the studies took into account for the diagnosis of adults with ADHD are presented, with only those reported in at least four articles included. Finally, the main instruments for the assessment of executive function processes were identified, with only those used in at least three studies for evaluating the same process considered in the analysis.

As shown in Table 2, the year in which the most articles meeting the inclusion criteria of the review were published was 2013 with 21.2%; followed by the years 2014 (15.2%), 2011 and 2017 (12.1% each).

Table 2 Characteristics of the sample of articles and participants

| Feature | Categories | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Year of publication | 2013 21% | |

| 2014 15.2% | ||

| 2011 12.1% | ||

| 2017 12.1% | ||

| Country of publication | United States | 42.4% |

| Brazil 12.1% | ||

| Germany | 9.1% | |

| Norway | 6.1% | |

| Israel 6.1% | ||

| Groups of participants | ADHD group / normal control group | 33% |

| ADHD groups with other characteristics such as (IQ, emotional dysregulation, other) | 27.3% | |

| ADHD group / ADHD medicated group | 21.2% | |

| ADHD group / psychiatric patients without ADHD group | 12.1% | |

| ADHD adult group only | 6.1% | |

| Age Range | 18 to 60 years old | 48.5% |

| 18 to 40 years old | 21.2% | |

| Not specified average age | 30.3% | |

| ADHD Subtype | No subtype specified | 66.7% |

| Combined ADHD subtype | 21.2% | |

| Inattentive ADHD subtype | 9.1% | |

| ADHD with comorbidities | 42.2% | |

| ADHD without comorbidities | 12.1% | |

| ADHD group with medication | No use of medications during the evaluation | 39.4% |

| At least one of the groups had medication | 21.2% | |

| Some participants were taking medication | 15.2% | |

| It does not specify medication use | 24.2% |

Source: The authors.

In terms of countries, USA is the pioneer in publications with 42.4% of the sample, followed by Brazil with 12.1%, Germany with 9.1%, Norway and Israel with 6.1% each.

In relation to the participant groups, less than 50% of the studies included different groups of patients varying according to the presence/absence of ADHD or characteristics such as medical history, medication, IQ, comorbidities, etc.

Almost half of the sample (48.5%) was aged between 18 and 60 years, 21.2% between 18 and 40 years, and 30.3% of the sample only specified the mean age.

Regarding ADHD subtypes, the majority of the articles (66.7%) did not specify which ADHD subtype the participants presented. In the articles that did report this data, a sample with ADHD of mostly combined type (21.2%) was evident.

The 42.4% of the articles reported that the ADHD group presented comorbidities, the most frequent being: mood disorders, substance abuse, and anxiety disorders.

Finally, 39.4% of the items reported that the ADHD group was not taking medication at the time of assessment, as those who were taking medication had withdrawal or stomach pumping between 24 and 48 hours prior to neuropsychological testing. A total of 21.2% had at least one group taking medication, and it was one of their variables. 15.2% mentioned that some participants were taking medication at the time of assessment but did not account for it in the results, and 24.2% did not specify whether participants were taking medication at the time of the assessment.

Table 3 presents the most frequently used sources in the sample of articles to diagnose ADHD in adults. The DSM IV was the most commonly used diagnostic manual, despite the DSM V being published in 2013. The majority of articles used at least 3 sources: interview, a participant self-applied instrument, and criteria from a diagnostic manual. The most frequently used instrument to assess ADHD symptomatology was the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS), used in 39% of the articles. Additionally, 21% of the items used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (SCIDV-R) and 18% used the Schedule of Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Aged Children, current and lifetime version (K-SADS) to confirm the presence of ADHD and/or disorders.

Table 3 Main sources and measures for the diagnosis of ADHD

| Diagnostic Criteria | Description | Number of articles | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| DSM IV | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, IV edition (1994). | 22 | 67% |

| The Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) | WHO scale that assesses the current frequency of the 18 DSM IV symptoms. The scale is used to detect possible cases in which a more detailed clinical interview would be efficient. | 13 | 39% |

| Interview by psychologist/psychiatrist | Interview by a professional psychologist or psychiatrist. | 11 | 33% |

| Interview by another | Interview by a trained person or general practitioner. | 10 | 30% |

| Previous diagnosis | Articles that reported obtaining the sample from a hospital, clinic, psychiatric entity, longitudinal study or only mentioned that there was already a diagnosis. | 8 | 24% |

| Third party interview/questionnaire | Interview with family members or another person close to the patient. | 8 | 24% |

| Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (SCIDV-R) | This is a semi-structured interview designed to establish the most important diagnoses of Axis I of the DSM-IV (1994). | 7 | 21% |

| DSM IV TR | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, IV edition (1998). | 6 | 18% |

| Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Program for School-Aged Children, Current and Lifelong (K-SADS) version | Semi-structured interview that assesses psychopathology categorically according to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. It allows establishing the age of onset and/or remission of symptoms in the present and throughout life. | 6 | 18% |

| WAIS-III | Clinical instrument for individual application to assess intelligence. | 5 | 15% |

| Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scales (CAARS) | It assesses the 18 symptoms that make up the DSM IV diagnostic criteria. There is one model for the patient and another for an external informant. | 4 | 12% |

| Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS-K) | To aid in the retrospective diagnosis of ADHD in childhood, this is a self-administered questionnaire. | 4 | 12% |

| DSM V | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, IV edition (2013). | 4 | 12% |

| ADHD Rating Scale, Self-Report Version (ADHD RS-SRV) | 18-item questionnaire that assesses attention deficit, hyperactivity and impulsivity that make up attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). | 4 | 12% |

Source: The authors.

Table 4 shows that the most evaluated process in the sample of articles was that of inhibition, assessed in 79% (N = 26) of the articles included in this review. Followed by working memory, evaluated by 67%(N = 22) of the articles, and then planning, which was included in 45%(N = 15) of the articles.

Table 4 Number and percentage of studies reporting significant differences in EF processes among the groups assessed

| Executive function processes | ADHD/ Normal Control | ADHD/ Psychiatric | ADHD/ Medicated ADHD | ADHD/ ADHD other | ADHD single group | % Total Significant | Total N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition | 8 - 67% | 3 - 100% | 1 - 33% | 3 - 43% | 1 - 100% | 62% | 26 |

| Working memory | 6 - 75 % | 2 - 100% | 2 - 50% | 4 - 67% | 2 - 100% | 73% | 22 |

| Planning | 3 - 60% | 1 - 50% | 3 - 60% | - | 2 - 100% | 60% | 15 |

| Attention - vigilance | 1 - 50% | 1 - 100% | 1 - 33% | 2 - 33% | 1 - 100% | 46% | 13 |

| Hot EF | 4 - 100% | 2 - 100% | 1 - 33% | 2 - 33% | 1 - 100% | 75% | 10 |

| General FE | 2 - 67% | 2 - 100% | 2 - 67% | 2 -100% | - | 80% | 10 |

| Set change | 5 - 100% | 2 - 100% | 1 - 50% | - | 1 - 100% | 90% | 6 |

| Sustained attention | 3 - 100% | 1 - 100% | - | 1 - 50% | - | 83% | 6 |

| Organization of materials | 2 - 100% | 1 - 100% | 1 - 50% | - | 1 - 100% | 83% | 6 |

| Task Monitoring | 2 - 100% | 1 - 100% | 1 - 50% | - | 1 - 100% | 83% | 6 |

| Selective attention | 1 - 100% | 1 - 100% | - | 1 - 50% | - | 60% | 5 |

| Processing speed | - | - | - | 1 - 50% | - | 20% | 5 |

| Self-monitoring | 2 - 100% | 1 - 100% | 1 - 100% | - | - | 80% | 5 |

| Fluency | 1 - 33% | 1 - 100% | - | - | - | 50% | 4 |

| Reaction time | 1 - 33% | - | - | - | - | 25% | 4 |

| Troubleshooting | - | - | 1 - 100% | 1 -100% | 1 - 100% | 75% | 4 |

| Cognitive flexibility | 1 - 50% | - | - | 1 -100% | - | 67% | 3 |

Note: Total N= The total number of articles that included each domain, even if they did not report significant differences.

Source: The authors.

The processes in which significant differences were found in all groups were: set switching (90%), sustained attention, organization of materials, and task supervision (83%), general EF and self-monitoring (80%), hot EF and problem-solving (75%), working memory (73%), cognitive flexibility (67%), inhibition (62%), and planning and selective attention (60%). In the fluency process, half reported significant differences (50%). Specific results comparing the groups will be explained in the discussion.

Table 5 compiles the most commonly used instruments for the assessment of the processes considered in the review. The most frequent were the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), Conners Continuous Performance Test (CPT and CPT II), Stroop Color Word Test (SCWT), Trail Making Test (TMT), WAIS-IV Digit Retention subtest, Go - no Go and Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF), each of these instruments were used in at least 5 articles.

Table 5 Most used instruments for the assessment of EF processes

| Process | Instruments |

|---|---|

| Inhibition | D-KEFS Color Word subtest, Stroop Color Word (SCWT), Stop Task, Go - No Go, The Attention Network Test (ANT) |

| Working memory | WAIS-IV: Digit Retention, Arithmetic/Digit and Symbol Retention, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), Trail Making Test (TMT), Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure (ROCF) |

| Planning | Continuous Performance Test (CPT), Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) |

| Attention - vigilance | WAIS-IV: Digit Retention, Continuous Performance Test (CPT), Trail Making Test (TMT), Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure, WAIS-IV: Digit Retention |

| General FE | Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF), Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) |

| Hot FE | Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scale (CAARS), Barkley Deficits in Executive Functioning Scale (BDEFS), Deficits in Executive Functioning Interview (DEFI), Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) |

| Set change | Change from D-KEFS Color Word Task and Verbal Fluency Task, Trail Making Test (TMT), Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB), WAIS-IV: Digits and Symbols |

| Sustained attention | Stroop Color Word (SCWT), Continuous Performance Test (CPT), Trail Making Test (TMT), Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure (ROCF) |

| Selective attention | Stroop Color Word (SCWT), Continuous Performance Test (CPT) |

| Processing speed | Trail Making Test (TMT), WAIS-IV: digits and symbols |

| Self-monitoring, organization of materials and task supervision | Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF-E) |

| Fluency | D-KEFS Fluency Task |

| Reaction time | Go - No Go |

| Cognitive flexibility | Stroop Color Word (SCWT), Trail Making Test (TMT) |

| Troubleshooting | Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF), Barkley Deficit in Executive Functioning Scale (BDEFS) |

Source: The authors.

Discussion

This study aimed to systematically review research on executive functioning in adults with ADHD published in the last decade. The sample consisted of 33 articles extracted from PubMed, Web of Science and EBSCO platforms. The information from these articles was organized by main characteristics of the study and the sample, findings in the EF processes that were most evaluated, instruments most used for such processes, and main sources and measures for the diagnosis of adults with ADHD.

The country with the highest academic production was the United States, with 14 articles. Western countries have the highest rates of ADHD, which in turn may imply greater interest in studying the problem, as well as greater support and funding; this has been reflected in a greater number of exponents on the subject, explanatory theories, instruments for diagnosis and evaluation of EF, most of which are from this country.

In Latin America, the country with the highest number of publications was Brazil 4. Argentina and Mexico contributed 1 article each. In the other Latin American countries, no studies were found that could be included in the sample, as they were studies on children or adolescents, or review articles. The above reflects a disparity, despite Latin America having about 36 million people affected with ADHD 12 and Colombia reporting a prevalence rate of up to 20% -being the highest in the region 17- research on the topic is not a priority.

Regarding the sources and measures used to diagnose ADHD in adults, the literature emphasizes clinical and psychosocial assessment, neurodevelopmental history, cognitive and behavioral assessment, as well as reports from close individuals 47. The selected studies used these sources to a greater or lesser extent, the most frequent being the clinical interview, diagnostic manual criteria, and the use of a self-applied instrument by the participant. Therefore, it is necessary to include more sources for the diagnosis of adults with ADHD, such as the evaluation of a third party and the collection of a complete medical history.

The most widely used diagnostic manual continues to be the DSM IV, despite criticisms for the diagnosis of ADHD in adults. One of its limitations is that it provides equal weight to each symptom when making diagnostic decisions, even though it is well known that not all criteria are equal to their ability to predict ADHD 47. The DSM V was published in 2013 and adds clarifications about the importance of each symptom, it also raises the age of manifestation of some symptoms from 7 to 12 years and points out the relevance of ADHD diagnosis in adults 3. This is why it is interesting that articles published after 2013 continue to use earlier versions of the DSM without clarifying the reason for their preference.

A total of 7,149 people were included in the evaluation of the EFs, 5,096 of whom were adults with ADHD. Almost all the processes assessed in the item sample are part of the cool EFs. The data included in the hot EFs were obtained from the emotional control component of the BRIEF, as none of the studies included in the sample assessed these EF processes with additional or different instruments; therefore, the high percentage of significance reported here (79%) should be taken with caution.

When comparing the performance of an ADHD group with a control group with no medical or psychiatric history, it was determined that there are significant differences in most of the EF processes, especially in inhibition, working memory, and planning and attention-vigilance. These differences coincide with the results of Barkley 48 and Cheung et al. 49, who mention that patients with ADHD present a deficient capacity of inhibitory control that generates alterations in the global executive functioning, this causes little motor and emotional regulation before a stimulus, failing to inhibit the execution of an immediate response, hindering planning, attention, problem-solving and other processes of executive functioning.

The EF processes in which no significant differences were found when comparing the performance of these two groups were processing speed, fluency, and reaction time. Since only 30% of people with ADHD show total neuropsychological deficits in tests measuring EF 50, the importance of not taking the neuropsychological test as the main tool for diagnosis and giving greater importance to developing individualized intervention procedures is emphasized 51.

Studies comparing adults with ADHD to those with other psychiatric disorders, but without ADHD, have reported significant differences across all the processes assessed, which suggests inner executive failures in ADHD patients. Most people in the control groups were diagnosed with mood disorders and anxiety disorders, EF deficits have been reported previously in patients with depression 52, bipolar disorder 52, generalized anxiety disorder 53, and obsessive-compulsive disorder 54. Few studies compare the EF deficits of an ADHD group with a group of people with other disorders, because the sensitivity and specificity of the instruments is lower than when comparing an ADHD group with a normal control group 55. The results presented here are in line with what Holst and Thorell 55 posit, the EF deficits of adults with ADHD are not only significant with a normal control group, but also with people who have different disorders. This statement requires more studies and information, as most of the results of the 4 articles included in this category were significant only in a small range.

Moreover, the studies that evaluated executive functioning with the use of a medication reported significant differences in the processes of planning, self-monitoring, and problem-solving, and found no significant differences in the processes of inhibition, working memory, attention, and hot EF. Regarding this group of articles, it should be noted that the medications used and the selection criteria in their participants varied. Most studies do not specify ADHD subtypes, comorbidities or the pharmacological treatment for these comorbidities, these diverse characteristics within the same experimental groups make the samples heterogeneous and the results may vary 56.

The variation in results may also be influenced by the difference in mechanism of action of each medication, the most used medications were methylphenidate and atomoxetine. Atomoxetine is associated with an improvement in sustained attention, inhibitory capacity, spatial planning and problem-solving 57. In contrast, while methylphenidate improves cognition in adults with ADHD, including improvements in attentional set shifting, spatial planning and problem-solving, it does not always normalize their performance levels. Therefore, combining pharmacological treatment with psychosocial intervention strategies and cognitive-behavioral therapy is essential to effectively improve the executive skills of adults with ADHD 58-59.

Regarding studies that related other variables in two ADHD groups, two of these were related to ADHD and IQ. The results of Milioni Chaim et al. 60, indicate that adults with ADHD and high IQ performed better on multiple executive functioning tests compared to those participants with ADHD and average IQ. This suggests that a higher IQ in adults with ADHD provides a wider range of strategies to compensate for deficits in EF. These findings may help explain why highly intelligent patients are often underdiagnosed when they are still children, as high IQ may mask their initial ADHD disorder 60.

Antschel et al. 61 compared a group with ADHD and high IQ to a control group with high IQ but no ADHD. They found that the ADHD group, despite having high IQ, performed worse than the high IQ group without ADHD. These results follow other studies suggesting the existence of a disparity between executive functioning and IQ, with the presence of executive deficits interfering with an individual's practical performance despite high IQ 60. Although this review only had two articles relating IQ level and ADHD, it shows the lack of existing consensus on the relationship between IQ and EF. It has been demonstrated the relative independence of IQ and executive functioning 62; nonetheless, there is also evidence that suggests a high correlation between these variables 63.

A study compared an ADHD group without functional impairment with an ADHD group with functional impairment, significant differences were not found in any of the EF processes 64. Functional impairment is understood as meeting the diagnostic criteria on the existence of clear evidence that symptoms interfere with or reduce the quality of social, academic, or occupational functioning. By finding no significant differences between the functionally impaired and non-functionally impaired groups, it was concluded that although adults with ADHD receive behavioral treatments (diary, task list, etc.) aimed at improving EF, this does not guarantee improvement in other aspects of the disorder such as impulsivity, which can more easily overload the social environment and ultimately lead to greater occupational and social disability than other features of ADHD symptoms 64.

Torralva et al. 65 compared an ADHD group with high neuropsychological performance (ADHDhi), an ADHD group with low neuropsychological performance (ADHDlo), and a control group. They concluded that the adults in the ADHDlo group differed significantly from the participants in the ADHDhi group and the participants in the control group, while the ADHDhi group and the control group showed similar performance. In this regard, the authors mention that it is common to find adult patients who meet DSM-IV criteria for ADHD but function normally on neuropsychological tests. Similarly, they point out that the results demonstrate how some executive deficits can hinder the proper functioning of some people with ADHD, while others manage to compensate for these deficits as they grow so that their performance in EF tests is similar to that of a normal group 65.

In the study by Surman et al. 66 the performance of an ADHD group and an ADHD group with deficient emotional self-regulation (DESR) was evaluated. It was found that the groups had no significant differences in test performance. Therefore, the study does not support the hypothesis that neuropsychological deficits are etiologically related to DESR in ADHD participants. That is, EF processes do not contribute to DESR, and any relationships found may be due to chance and require confirmation. These results are contrary to previous studies in which neuropsychological deficits were found to be associated with DESR in adults with ADHD 67. This disparity in findings may have implications for understanding the etiology of DESR among ADHD patients.

Kamradt et al. 68 made a comparison between an ADHD group with moderate sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) and an ADHD group with severe SCT. SCT is understood as a condition in which the main symptoms are slowing of mental processes, tendency to daydream, hypo activity, frequent forgetfulness, and lethargy 69. In this study, the moderate SCT group showed greater deficits in working memory than the severe SCT group. These results could be attributed to the fact that moderate SCT symptoms are particularly associated with difficulties on specific neurocognitive tasks 70. Even given the understudied nature of this association, it is speculated that individuals with moderate SCT, may represent a subgroup of ADHD adults with neurocognitive impairment. Only one study has examined SCT in relation to neuropsychological performance in adults 71, and it found that neither SCT nor ADHD symptoms predicted neurocognitive performance in adults.

Gisbert et al. 72 compared ADHD groups with high and low emotional lability, finding low results in the former. Emotional lability is characterized by irritability, short temper, sudden and unpredictable shifts towards negative emotions contributing to functional impairment in youth and adults with ADHD 74. This can increase the severity of ADHD symptomatology as well as comorbid disorders 75. Furthermore, ADHD and emotional lability could be associated with processes related to amygdala dys-regulation 72, however, current research does not present sufficient evidence for this.

When comparing an ADHD group using cannabis with a non-using ADHD group, no significant differences were found in the processes, the differences were between those with ADHD -users or nonusers- and those in the normal control group 76. The study did not show that cannabis use directly influenced the performance of participants with ADHD, but it found that clearly a diagnosis of ADHD had a much greater impact on EF than cannabis use, perhaps because ADHD is associated with developmental delays, particularly in the prefrontal cortex 77.

Finally, the two single-group studies of ADHD found below-expected performance on several EF processes, except self-monitoring 78-79. These studies related EF to quality of life and found correlations with small, medium, and large effects in all aspects despite the samples having different characteristics, one consisting of college students aged 18-36 and the other of adults aged up to 58. These findings support the established links between ADHD, impaired EF, and major life activities found in the adult ADHD literature 80.

Although in most of the processes the homogeneity among the studies was acceptable, it should be noted that the sample selected according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria is small, and most of the articles did not specify relevant data such as comorbidities and their treatment, ADHD subtypes of their sample, and used only self-reported instruments or different instruments to assess different processes of EF. These poorly controlled variables may reduce the reliability of the results presented. These issues are discussed in more detail below.

Regarding comorbidities, although part of the deficits presented are due to ADHD, there is an impact on neuropsychological characteristics that occurs due to associated comorbidities that intensify specific deficits 81. The comorbidities reported to a greater extent by the studies were mood disorders and anxiety disorders. The emotional instability and impulsivity in these disorders could generate a greater number of errors in the resolution of the tests 82. The low report of comorbidities and the null association of these with the results of EF, shows that few studies have addressed the possibility that specific neuropsychological deficits in ADHD can be attributed to comorbid disorders 83.

About the instruments for the evaluation of EF processes, some problems were evidenced that may make it difficult to understand the results and clarify the relationship between ADHD and EF. For example, different tests are used to measure the same neuropsychological function, different versions of the same test are used, or a single test is used to measure all executive functioning. Regarding the latter, assessing EFs with only a self-report is very common, and the sole use of this type of instruments generates lower reliability, as it may cause an over-or under-estimation of symptoms by the patients themselves 56. As a result, the clinical utility and accuracy of such tasks for identifying EF-related impairments are limited 84.

In reference to the subtypes of ADHD, it is known that the most diagnosed subtype worldwide is inattentive, followed by combined and then hyperactive, which was also reflected in the samples of the articles. However, the subtypes were not reported in 66.7% of the articles and most of the studies that mentioned them during the description of their sample, were not taken into account later to determine whether they influenced the performance of the participants. Knowing the subtypes and including them in the analysis is a relatively underexplored area, even though there is a well-known theory about differences in the performance of neuropsychological tasks by people with ADHD. This theory proposed by Barkley 48 suggests that the deficits of inattentive ADHD tend to occur in memory tasks, focused attention and processing speed, while the deficits of hyperactive ADHD tend to be in aversive delay, problem-solving, cognitive flexibility and sustained attention. In the present review, it was not possible to assess the influence of subtype due to the limited information provided by the selected sample of articles.

In sum, this research compiled open access articles from the last decade that evaluated EF in adults with ADHD, seeking to contribute to the dissemination of studies related to a health problem that remains understudied. The results obtained by the research varied according to their characteristics, but most of them found deficits in executive functioning in adults with ADHD. These results confirm the heterogeneity of the disorder and the need to continue further research on the subject, because as mentioned there are different variables that can influence the results, such as subtypes, instruments used, comorbidities, and medication, among others. In addition, this field of research is even less studied in geriatric population and the information on hot EF is limited, since they are not usually evaluated in a specific and rigorous way.

Conclusions

The study of executive functioning in adults with ADHD is a topic that has recently gained global interest, resulting in a relatively small number of publications to date. In the particular case of Latin America, only 6 articles were obtained, belonging to Brazil, Argentina and Mexico. No articles from Colombia were found that met the inclusion criteria, highlighting a clear need for more research on the subject in the country. According to the results presented here, there is a high percentage of adults with ADHD who present a deficit or lower performance in EF tests, compared to normal control adults and even adults with other psychiatric disorders. Nonetheless, these deficits vary by processes and specific characteristics of the sample, which confirms the heterogeneity of the disorder and leaves open the field of research.

Variables of interest for this review, such as subtypes, comorbidities and medication, are not usually specified or taken into account during the methodology or results of the studies. The impact of these variables remains unclear and warrants further research, since as illustrated, they can be very influential in how adults with ADHD perform not only in their daily lives, but also in different EF tests.

The instruments used to assess EF were standardized and reliable according to one of the selection criteria. These instruments assessed specific EF processes, or general EF in a primarily self-administered fashion, so performance on these does not provide information about day-to-day functioning in complex situations that demand integrative executive processing. Including ecological executive tests that resemble more closely real-life demands may provide another perspective and yield results that contribute to clarifying the relationship between adult ADHD and EF.

This research has not received specific grants from public, commercial, or nonprofit funding agencies. The authors declare the absence of any potential conflicts of interest and state that there are no ethical implications for the reader to consider.