Introduction

Crystal-associated mucosal injury is an important clinical entity that has been gradually increasing, specifically, derived from the use of medications for chronic kidney disease (CKD). In patients with CKD, non-absorbable medications that facilitate ion exchange are part of the treatment options for electrolyte imbalances like hyperkalemia and hyperphosphatemia. There are 3 types of resins described in the literature: Bile Acid Sequestrants (BAS), Kayexalate, and Sevelamer. Kayexalate, a potassium-binding agent, and Sevelamer, a phosphate-lowering medication, are known for causing significant mucosal abnormalities. Nevertheless, literature is limited to case reports and a causal relationship has not yet been established, therefore little is known about the pathophysiological mechanism of mucosal injury.

The known pathologic effects of phosphate-lowering agents in the gastrointestinal tract were first described in 2013 by Swanson et al. in a case series of 15 patients with mucosal injury secondary to Sevelamer. Findings included ulceration, ischemic injury, necrosis, and inflammation1. Since then, few cases of symptoms associated with resin administration have been reported. Similar to Sevelamer, Kayexalate-related mucosal injury is rare but may be associated with fatal gastrointestinal injury; a systematic review reported a mortality rate of 33%2.

BAS agents are another type of resin polymer that targets certain components in bile. These medications are mainly prescribed to treat diarrhea and hypercholesterolemia and have been safely used for several years3. Cholestyramine, a BAS agent, prevents the reabsorption of cholesterol found in bilis; therefore, it is prescribed for the management of hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in patients with CKD. The agent has been associated with minimal adverse effects localized to the gastrointestinal tract without systemic repercussions. Accordingly, the main harmful effects described in the literature consist of esophagitis, gastritis, reactive gastropathy, erosion, and ulcers3. Although Cholestyramine is considered biologically inert and has been safely used for several years, we present a case series with histological description of 2 patients with crystal mucosal injury associated with Cholestyramine and Kayexalate consumption that required surgical treatment.

Materials and methods

Two specimens with histological similar crystals were collected from biopsies of two patients that arrived at our academic center over a 6-month period. Both samples were fixed with formalin and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For each of the two cases, we evaluated the presence and distribution of the BAS crystals, mucosal injury and other conditions that could have contributed to the patient’s clinical presentation.

Results

Clinical Features

Case #1

An 86-year-old female patient underwent elective surgery for colovaginal and colovesical fistula with sigmoidectomy. The patient had a previous right colectomy in 2015 secondary to a malignant colonic tumor. She has a history of hypertension, gastritis, diverticulosis, and hypercholesterolemia that was being managed with cholestyramine.

Case # 2

An 83-year-old male patient presented to the emergency department with hematochezia associated with several blood clots, asthenia, adynamia, and dyspnea on exertion. On his arrival at our institution, he was hemodynamically unstable. He has a history of CKD with peritoneal dialysis requirement. Laboratory analysis revealed severe anemia (6.3 g/dL), creatinine of 8.4 mg/dL, and serum potassium of 6.4 mEq/L for which Kayexalate was administered. An endoscopic study was negative for upper gastrointestinal bleeding, but colonoscopy showed an abundance of clots in all colonic surfaces and multiple diverticula confined to the ascending colon.

The patient was admitted for radiological embolization followed by ICU admission, he required major hemorrhage protocol transfusion twice with over 10 units of blood. Finally, he was taken to the operating room where an exploratory laparotomy and subtotal colectomy were performed with aid of an intraoperative colonoscopy.

Pathologic Features

Case #1

Two resected colon specimens were studied in the pathology department and several diverticula were found. The diverticula had a wide base (measuring between 0.5 and 0.3 cm) surrounded with fibrosis and vascular congestion. Additionally, from the peri-intestinal adipose tissue, 5 nodular lesions were isolated; one of them with dimensions of 0.6cm x 0.5cm and the other one of 0.3 cm x 0.2 cm. As observed in Figure 1 the diagnosis of diverticulosis associated with several intramural and mucosal crystal foci, very likely from cholestyramine, was made. It was not possible to state a causal relationship between the presence of crystals and the acute severe inflammation and perforation of the diverticula.

Figure 1 Sigmoid colon with complicated diverticular disease and areas of diverticulitis. Intramural abscesses and multiple magenta-colored crystals, with angled edges and salmon-colored striations on the inside. Additionally, crystals are found primarily on the mucosal surface, in close relationship to the diverticula.

Case #2

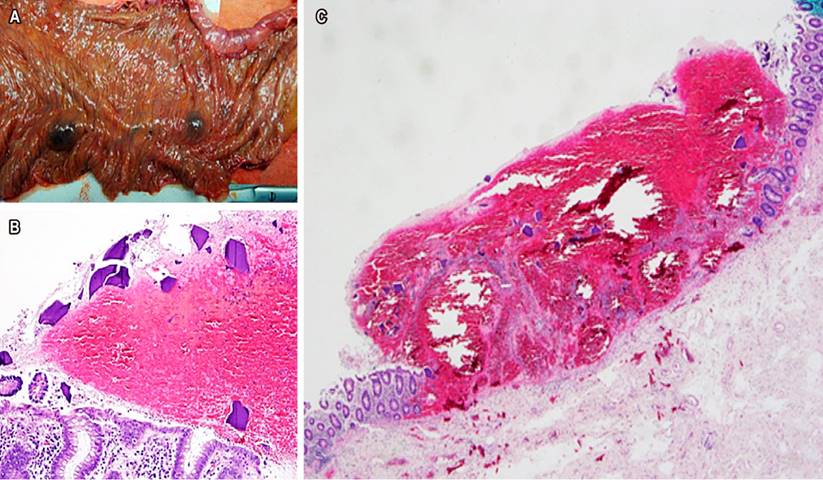

The surgical pieces were analyzed in the pathology department. Figure 2 shows a macroscopic picture of a colonic segment with multiple raised hemorrhagic lesions and microscopic examination showing crystals, ulceration, and ischemic necrosis.

Figure 2 A. Colon segment with multiple hemorrhagic raised lesions. B. Hematoxylin and eosin 20 x closeup to appreciate crystal morphology. C. Hematoxylin and eosin 40 x closeup that shows ulceration and ischemic necrosis, presence of magenta-colored crystals in the surface of the hemorrhagic material.

Discussion

Theoretically, the increased number of performed endoscopies, together with the increase in polypharmacy in the context of an aging population, should raise the probability of observing unintended side effects of therapeutic medications. Nevertheless, medication-induced injury is underrecognized and it is very uncommon for pathologists to report resins on specimens. An online survey performed in 2016 by the Rodger C. Haggitt Gastrointestinal Pathology Society informed that 75% of 99 pathologists with a GI subspecialty had never seen resin administration documented on the pathology4.

Physiopathology

After an extensive review of the literature regarding mucosal injury derived from the use of cation-exchange resins, a cause-effect relationship has not yet been reported but literature has described the potential of Kayexalate to cause transmural colonic infarction due to rapid electrolyte shifts in the context of uremic patients who are vulnerable because of gastrointestinal vascular instability5. Particularly, factors that can predispose to injury aside from uremia, include slow gastrointestinal tract motility, immunosuppression medication, and hemodynamic changes associated with hemodialysis and surgery6.

The use of cholestyramine has been described to lower the risk of BAS-associated mucosal injury since it diminishes the cytotoxic effects of deoxycholic acid therefore preventing endoplasmic reticulum stress that ultimately results in disruption of the mucosal barrier7. Although this is true, preliminary studies in rats showed an insignificant effect of cholestyramine treatment on preventing mucosal injury and they attributed this ineffectiveness to the pKa of bile salts converting them to their nonionized form at the gastrointestinal tract pH, impending cholestyramine-induced bile acid sequestration8. Nevertheless, no pathologic relationship with cholestyramine was described before and the exact mechanism is misunderstood; therefore, only an association can be established.

Diagnosis

Bile acid sequestrants are classically seen along the gastrointestinal tract as bright orange in hematoxylin-eosin with a rectangular shape and a glassy texture, nevertheless, as seen in Figure 1, non-classical morphology (usually focal) concerning shape, color and location can be observed depending on the variable substrate binding and background pH. In hematoxylin-eosin, BAS are eosinophilic polygonal crystals but can be dull yellow on acid fast bacillus special stains. They have been classically described as rectangular but recently rounded structures have been described as well9. Furthermore, crystals have been found not only in the GI tract but also in unusual locations such as cutaneous deposition, gall bladder in patients with biliary stenting, and in a separate surgical resection of a necrotic pancreas4.

Moreover, Kayexalate’s morphology is highly specific, showing rhomboid nonpolarizable, basophilic crystals with a mosaic pattern; its only differential diagnosis consists of cholestyramine-crystals which are also basophilic and angulated but with a greater opacity and no mosaic pattern5. Altogether, the best method to identify these crystals is acid-fast bacillus special stains where Sevelamer is seen as magenta-colored crystals, as presented in our case, Kayexalate as black-colored crystals and BAS as dull yellow crystals3. The high spectrum of crystal presentation tends to be focal, and the typical resin morphology should be found in the surroundings, therefore the slide must be scanned as a whole. Although there are several characteristics particular to each resin, most of the time they are histologically indistinguishable from each other, and accurate distinction is important since Kayexalate and Sevelamer have a stronger association with mucosal injury than Cholestyramine-crystals3.

Treatment

Recognition and topline descriptive report of resins, particularly of Kayexalate and Sevelamer, in association with mucosal injury, should be treated as a clinical emergency for adequate monitorization and prevention of detrimental outcomes. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that the effects of the medication are known to mimic other endoscopic and radiologic diagnoses in the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and colon such as colonic pseudotumor6. Still, a low suspicion threshold must be considered since it is important to alert the clinician of the potentially dangerous consequences of Kayexalate and Sevelamer when a mucosal injury is observed in the specimen since Abraham et al. found that nearly 30% of patients with ileal or colonic injury had extensive necrosis requiring resection10. Therefore, recognition of resin crystals in histologic sections as a marker for resin-associated mucosal damage may aid in establishing the correct diagnosis for clinically or endoscopically misleading lesions.

Prevention

Even though a good number of cases relating to BAS-associated mucosal injury have been reported, no successful prevention or treatment other than surgical resection is mentioned1,2,8-11. One case report even described how gastrointestinal ulcers and bleeding started after the first dose of Kayexalate12. Because the mechanism behind crystal-associated mucosal injury is not well understood, the specific settings where resins must be used with caution are not yet established and no standardized recommendations are available. Nevertheless, it has been suggested based on one retrospective observational study carried out by Panagiotis I et al, that a low dose of BAS can be well tolerated and could effectively normalize electrolyte abnormalities13.

Conclusion

In conclusion, given that it has been recognized that resins such as Sevelamer and Kayexalate can produce a large spectrum of fatal mucosal lesions, early diagnosis is critical to decrease mortality as well as improve prognosis. The latter makes it possible to indicate a feasible association between crystals in the colonic intestinal mucosa and critical inflammation. Nevertheless, establishing whether the consumption of Cholestyramine and Kayexalate and the deposit of its crystals in the gastrointestinal tract is the causal factor of mucosal injury, is uncertain. However, we cannot exclude their ability to cause mucosal injuries in specific settings and the presence of resins should prompt the pathologist to seek a related diagnosis to prevent deleterious outcomes.

text in

text in