Introduction

Technological advances in agricultural practices and production systems allow for the expansion of agriculture into areas with sandy soils. Nowadays, agricultural production in this type of soil is extensive, particularly in the state of Mato Grosso in Brazil (IBGE, 2017) that is now considered a hub for agribusiness. Grain production in the area also stimulated the growth of animal husbandry, particularly pig and cattle farming. Integration of crop and animal production systems allows farmers to use animal manure as fertilizer. This practice reduces costs and increases soil nutrient content and water retention but, at the same time, it can have detrimental consequences if animal manure is applied in excess (De Vrieze et al., 2019) since it has a high content of heavy metals such as copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), and cadmium (Cd).

Intensive application of swine manure can promote the accumulation of heavy metals in soils and the contamination of waterways through runoff and leaching (Zhang et al., 2003; He et al., 2005). This contamination can pose a risk to human health due to accumulation through the food chain (Scherer et al., 2010). Soil remediation is based on the use of chelating agents to immobilize metals and avoid uptake by plant roots, as well as leaching. This process is usually expensive and time- and resource-consuming (Wuana & Okieimen, 2011; Yao et al., 2012; Paz-Ferreiro et al., 2014).

The organic matter of agricultural residues has the potential to act as a biosorbent, and, thus, it can help mitigate contamination from heavy metals in soils and water streams (Sud et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2018; Purakayastha et al., 2019). Biosorbents can act through complex processes, such as ion exchange, adsorption on surface and into pores, complexation, chelation, etc. (Puls & Bohn, 1988; Sud et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2019). The management of this type of residues in tropical regions can be very challenging due to environmental conditions that increase the rate of soil organic matter mineralization and decomposition.

A potential solution for residue stabilization in these areas is the use of biochar. Pyrolysis provides a promising method for the treatment of animal manure with the advantages of destroying pathogens, breaking down antibiotics, producing value-added energy and biochar products, immobilizing heavy metals, and reducing the volume of waste stream (Tian et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019).

When applied to soils, biochar can have several beneficial properties. It can increase the amount of recalcitrant organic matter in soils, improve nutrient and water retention, decrease greenhouse gas emissions, and increase the soil capacity for heavy metal retention (Woolf & Lehmann, 2012; Bartoli et al., 2020). Transforming agricultural residues into biochar can be useful for improving soil chemical and physical properties and mitigating soil contamination by heavy metals. However, more research is still needed in the use of biochar for heavy metal immobilization. Biochar properties vary depending on pyrolysis temperature and time, the biomass used to produce the biochar, and the dose and the type of soil that biochar is applied to (Zheng et al., 2013; Abujabhah et al., 2016). For example, Shen et al. (2020) indicate that the characteristics and speciation of heavy metals in the biochar produced from pig manure are affected by the pyrolysis temperature. Between 500°C and 700°C is the ideal temperature for improving the characteristics of the biochar structure. In addition, the pyrolysis process can immobilize heavy metals, transforming unstable fractions into more stable fractions, and reducing environmental risk.

This study focused on the use of biochar from swine manure, one of the main residues produced in agricultural systems in the state of Mato Grosso. Swine manure is heavily used as fertilizer in sandy soils as a potential mitigation strategy for zinc (Zn) and cadmium (Cd) contamination in this type of soil. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the capacity of an Ustoxic Quartzipsamment soil and the mixture of soil with swine manure biochar to adsorb Zn and Cd, and the chemical changes conferred to the soil after adding the biochar.

Materials and methods

Soil collection and biochar production

Soil classified as an Ustoxic Quartzipsamment (91% sand, 4% silt, and 5% clay) (Soil Survey Staff, 2014) was collected from the 0-0.2 m layer from an agricultural area located in the city of Campo Verde, Mato Grosso, Brazil (15°13'55.2" S, 54°57'43.4" W). The soil was dried and sieved (2 mm) and its chemical properties were analyzed according to the methodology described by MAPA (2017) and Teixeira et al. (2017). Soil pH was measured with a pH meter in a soil solution of 1:2.5 distilled water. To determine the contents of sodium (Na+) and potassium (K+), the soil was extracted with a NH4CH3CO2 buffer (pH = 7). Na+ and K+ were determined using a flame photometer (model Pegassvs II, Tecnow, Maringa, Brazil).

To determine the contents of manganese (Mn) and phosphorus (P), the soil was extracted with a 1:1 solution of H2SO4. Mn was determined by measuring the solution's absorbance at 550 nm, and P was determined by measuring the absorbance at 660 nm. The contents of calcium (Ca2+), magnesium (Mg2+), iron (Fe3+), zinc (Zn2+), cadmium (Cd+2) and copper (Cu2+) were determined by acid digestion of the soil with HCl and metal concentrations were measured using an atomic adsorption spectrometer (SpectrAA 50 Varian, Mulgrave, Australia).

Swine manure biochar (SMB) was commercially produced (SPPT, Mogi Morim, São Paulo, Brazil) via slow pyrolysis at 400°C for 17 min. After pyrolysis, the biochar was sieved and homogenized to obtain a particle size of 0.5 mm. The chemical properties of SMB were determined following the methodology described above (MAPA, 2017; Teixeira et al., 2017).

Soil density and porosity were analyzed according to the method described by Teixeira et al. (2017). For soil bulk density (ρd), 35 ml of dried soil was measured in a graduated cylinder, and Equation 1 was applied:

where ρ d is the soil bulk density (kg dm3), m is the mass of dried soil added to the cylinder (g), V is the volume of soil in the cylinder (cm-3), and f is a correction factor for soil humidity.

Soil porosity was obtained using Equation 2:

where P is the soil porosity, ρ p is the difference between total porosity and volumetric humidity at field capacity (θcc), and ρ d is the soil bulk density.

Soil-biochar mix characterization

Soil samples were incubated with different doses of SMB (0, 0.25, 0.75, 1.5 and 3% (w/w)) for 30 d. Soil moisture was kept constant at 60% of the soil water holding capacity, and temperature was maintained at 25°C (Souza et al., 2007).

After the incubation period, the chemical properties of the mixture were determined using the methodology previously described by MAPA (2017) and Teixeira et al. (2017). Total organic carbon (TOC) was determined by wet combustion, following the methodology of Yeomans and Bremner (1988). Organic matter from soil was oxidized with a mixture of 10 ml of 0.167 potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7) and 20 ml of concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4) while stirring it to ensure good mixing of the soil with the reagents. The excess K2Cr2O7 was then titrated with (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2 and TOC was estimated as the equivalent of K2Cr2O7 that reacted with the soil. Labile carbon (LC) was determined using the method proposed by Blair et al. (1995) and adapted by Shang and Tiessen (1997) that consisted of the partial oxidation of soil carbon with KMnO4 0.033 M. The amount of oxidized C was calculated and considered as the labile component of soil organic C. Non-labile carbon (NLC) was determined as the difference between TOC and LC.

Sorption essays

Sorption essays were performed separately for each metal. Twenty ml of aqueous solutions of Cd (CdCl2) and Zn (ZnCl2) at different concentrations (0, 2.5, 5, 10, 50 and 100 mg L-1) were added to 50 ml falcon tubes containing 2 g of soil or soil-biochar mixture. The samples were then agitated for 24 h at 120 rpm and subsequently centrifuged for 15 min at 9000 rpm and filtered. The temperature was kept constant at 25°C. Metal concentration in the supernatant was measured using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (SpectrAA 50 Varian, Agilent technologies, CA, USA). Characterization tests and analyses were performed in four replicates within a completely randomized design.

The concentration of metals adsorbed in soil was calculated as the difference between the initial concentration of metals added and the concentration of metals that remained in the solution (Harter & Naidu, 2001), according to Equation 3.

where Qe is the concentration of metals in soil (mg kg-1); Co and Ce are the initial concentration of metals and concentration of metals in the solution (in equilibrium), respectively (mg L-1); Vol is the volume of the metal aqueous solution added to the falcon tube (L), and m is the amount of soil added to the falcon tube (kg).

Sorption efficiency was calculated using Equation 4.

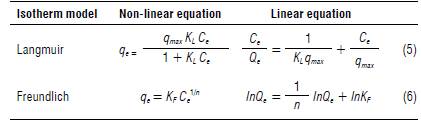

The Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms were then used to understand the equilibrium behind metal sorption to the surface. The equations are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1 Langmuir and Freundlich equations.

Qe - concentration of sorbate adsorbed by the surface in the equilibrium (mg kg-1); qmax - maximum sorption capacity (mg kg- 1); KL - Langmuir distribution constant (L mg-1); KF - Freundlich distribution constant (mg kg-1); Ce - sorbate concentration in the equilibrium solution (mg L-1), and n - heterogeneity parameter.

Although linear and non-linear models are mathematically equivalent, linearization often can introduce bias and increase the error distribution (Bolster & Hornberger, 2007). To avoid these errors, we fitted the Langmuir and Freundlich non-linear models using the R package 'PU-PAIM' version 0.2.0 that provides a collection of isotherm models, and the software R version 4.0.3 and RStudio version 1.3.1093.

Results and discussion

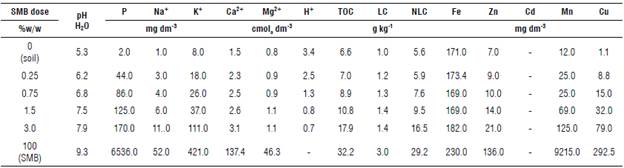

Soil-biochar chemical and physical properties

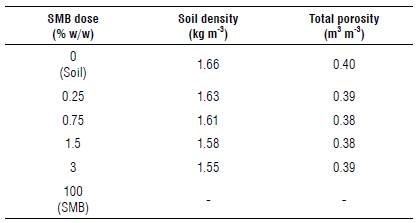

Biochar application had a significant effect on soil chemical and physical properties (Tab. 2). SMB addition increased soil pH. Soil without biochar had a pH of 5.3, and it increased to 7.9 with the highest SMB dose. Previous studies (Rondon et al., 2006; Houben et al., 2013) show that these changes can be attributed to the high ash content in biochar. Ash is mainly composed of alkaline metal oxides that can interact with the soil solution and release bases and other ions, increasing the pH (Steenari et al., 1999; Glaser et al., 2015). Another factor that may be related to the increase in pH is the alkalinity of the biochar caused by the presence of organic (-OH, -CO, -C=O, -COOH, -COH) and inorganic (-PO4 3-, -Si-O-Si) functional groups, and inorganic halogens (KCl and CaCl2). These groups belong to negatively charged surfaces (-COO- and -O-) that can capture protons from the solution (Tsai et al., 2012; Martinsen et al., 2014; Ding et al., 2016). This may also explain the decrease in H+ with the increase in the dose of biochar shown in TOC, LC and NLC also increased with the addition of SMB. As SMB is a substance with high carbon content (Wu et al., 2012; Speratti et al., 2017), the addition of biochar to the soil provides the necessary carbon sources for carbon cycling. Likewise, biochar can provide the soil with complex aromatic structures that increase NLC (Woolf & Lehmann, 2012) or labile compounds, such as aliphatic carbon compounds, increasing the LC content in the soil mixture.

TABLE 2 Soil chemical properties before and after swine manure biochar (SMB) addition.

(-) Below the limit of detection. TOC - total organic carbon, LC - labile carbon, NLC - non-labile carbon.

Additionally, after SMB application there was a significant increase in the content of macro and micronutrients (P, Zn+2, Cu+2, Mn +2, Na+, K+, Ca+2, Mg+2) (Tab. 2). This is due to the type of organic matter used for biochar production. Swine manure usually has a high concentration of these nutrients, so when SMB is produced, it inherits these compounds (Tsai et al., 2012; Ding et al., 2016; Subedi et al., 2016).

Although there are many studies that show that biochar can increase soil porosity and improve water holding capacity and nutrient retention (Kuzyakov et al., 2014; Ajayi & Horn, 2017), soil porosity did not change significantly with SMB while soil density decreased slightly with the increases in SMB doses (Tab. 3). One possible explanation is that, although the number of pores did not change, its distribution on the surface did. Speratti et al. (2017), using the same biochar as in this study, performed a BET analysis to obtain the pore size and distribution of swine manure biochar and found that SMB had a total surface area of 7.2 m2 g-1 and a total pore volume of 0.0002 cm3 g-1 (micropore area was 0.7 m2 g-1 and mesopore area was 4.1 m2 g-1). Considering this, biochar particles could have changed pore characteristics like size, shape, connectivity, and volume and, therefore, changed nutrient, water, and heavy metal retention. For example, Liu et al. (2006) report that small biochar particles could enter bigger soil particles, decreasing its size.

Cadmium and Zinc sorption

Sorption isotherms

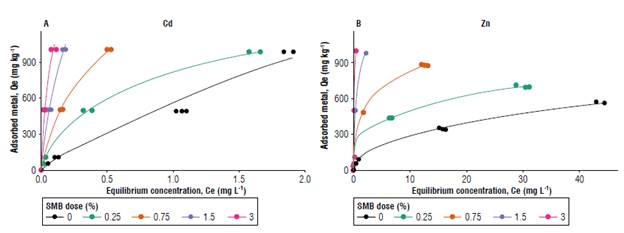

Results from the sorption assays showed that the amount of adsorbed metal to the surface increased with biochar application (Fig. 1). This effect was particularly evident for a higher concentration of the metal solutions (>50 mg L4) and higher SMB doses. Considering these data, Freundlich and Langmuir isotherms were used to evaluate metal sorption to soils with and without SMB addition. Table 4 summarizes the results obtained for the sorption essays.

FIGURE 1 Equilibrium concentration (Ce, mg L-1) vs. amount of adsorbed metal (Qe, mg kg-1) for A) cadmium (Cd) and B) zinc (Zn) and for every dose of swine manure biochar (SMB) applied.

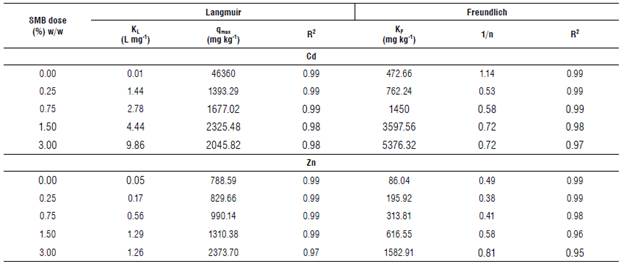

TABLE 4 Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm coefficients for Zn and Cd with and without swine manure biochar (SMB) addition to soil.

KL - Langmuir distribution constant (L mg-1), qmax - maximum sorption capacity (mg kg-1), KF - Freundlich constant (mg kg-1), n - heterogeneity parameter, R2 - goodness of fit measure for each regression.

The Langmuir model is based on the hypothesis that, when molecules are adsorbed into the surface, they form a single, uniform layer that covers the whole surface. The Langmuir constant (KL) is a parameter related to the affinity of metal ions to the sorption sites, and qmax is the maximum absorption capacity of the material. The Langmuir model showed a good fit for soil with and without SMB (R2 varied between 0.97 and 0.99, for both Cd and Zn). KL and qmax increased with the dose of SMB for all the cases, except for soil without biochar in which qmax for Cd was almost 20 times higher than qmax for a SMB dose of 3%. So, KL of 3% SMB was larger than KL of soil for Cd, but qmax was larger for soil without SMB. Since higher KL values indicate that the interaction between adsorbate and adsorbent is stronger, and lower KL values indicate a weaker interaction, this could mean that, although the soil has more sorption sites for Cd, biochar binds Cd stronger than soil. This could also indicate that SMB application favors chemisorption (stronger interactions, monolayer adsorption) over physisorption (weaker interactions, multilayer adsorption) that could be explained by the increase in functional groups that can bind the Cd to the surface (Ho & McKay, 1998; Kolodyhska et al, 2012; Wang et al, 2020).

The Freundlich isotherm is valid for heterogeneous surfaces and considers a multi-layer adsorption to explain the relationship between sorbate and adsorbent. This model had a good fit for both metals and all the concentrations of SMB used (R2>0.95). In the Freundlich isotherm, KF is related to the adsorption capacity of the surface, and n is a parameter related to the intensity of adsorption. If 1/n<1, adsorption is favorable; if n = 1, the partition between the two phases is independent of the concentration; finally, if 1/n>1, it means that adsorption is cooperative (Komkiene & Baltrenaite, 2016).

For Cd, KF increased with the dose of SMB (Tab. 4). Initially, the soil without SMB had a KF = 472.66 mg kg-1 and increased to 5376.32 mg kg-1 with the highest dose of SMB; this was an 11-fold increase in KF. In the case of Zn, the same trend was observed. Soil without SMB had an initial KF of 86.04 mg kg-1 and increased to 1582.91 mg kg-1 with 3% SMB (18-fold increase). When comparing the KF for both metals, KF for Zn was lower than KF for Cd for every SMB dose (values 3-6 times higher for Cd than for Zn). Park et al. (2015) and Chen et al. (2019) also find that biochar increases the soil's capacity to retain heavy metals, and that adsorption is up to 6 times higher for Cd than for Zn.

The intensity of adsorption (n) of the metals also changed with biochar addition. For Zn, 1/n was always lower than 1, suggesting that adsorption of the metals to the surface was favorable. In the case of Cd, 1/n was higher than 1 without biochar, indicating cooperative adsorption (i.e., the amount of metal adsorbed to the surface had an effect on the adsorption of new metal ions to the surface). With the addition of biochar, 1/n was lower than 1, indicating that the adsorption was favorable. That difference in 1/n between the soil and the soil with SMB for Cd was also an indication of different mechanisms of interaction between Cd and the surface when SMB is present.

Although both models were able to explain the data, the Langmuir isotherm was slightly better than the Freundlich isotherm, particularly for higher doses of SMB. This effect has also been observed in other studies with biochar and is attributed to the monolayer adsorption that occurs in the biochar surface (binding sites in the surface over electrostatic interactions) (Kolodyhska et al., 2012; Park et al., 2015; Wang et al, 2020).

Sorption efficiency

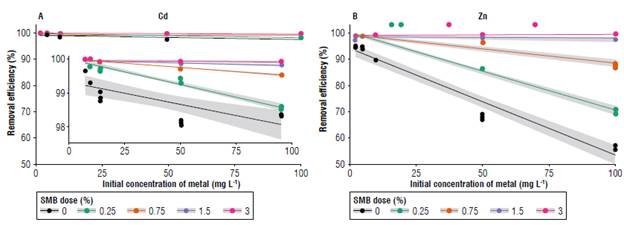

The sorption efficiency was used to evaluate the capacity of soil (with and without biochar) to retain Cd and Zn (Fig. 2). Soil without SMB addition was very efficient in removing Cd from the solution, even for high doses of the metal (efficiency = 97%). Sorption efficiency increased with biochar application. Doses of 1.5 and 3% SMB showed a sorption efficiency of ~100% for all the studied Cd concentrations (0, 2.5, 5, 10, 50 and 100 mg L-1).

Sorption efficiency for Zn without SMB application was high for low metal concentrations (~90% for Zn concentrations of 0, 2.5, 5 and 10 mg L-1). However, for higher concentrations of Zn (>50 mg L-1), sorption efficiency to the surface decreased to ~50%. Soil-SMB mixture had a sorption efficiency of ~100% for lower Zn doses (≤10 mg L-1) and it varied between 70-100% for higher SMB doses (depending on Zn initial concentration).

This increase in sorption efficiency with SMB application was expected, as biochar characteristics favor metal retention (Mohamed et al, 2018). Particularly, SMB has different functional groups (e.g., COOH, phenolic, etc.) that are sorption sites for cations by forming metallic complexes (Wuana & Okieimen, 2011; Rees et al., 2014).

Figure 2 also shows that the relationship between SMB dose and sorption efficiency is different for both metals. Efficiency for Cd was higher than that for Zn for all SMB doses and even for soil without SMB. This difference could be related to the chemical properties of each metal, such as electronegativity and ionic radius. Zn and Cd show electronegativity values of 1.66 and 1.46 and ionic radius values of 0.074 and 0.098, respectively (Liu et al, 2006). Puis and Bohn (1988) show that the retardation factor (i.e., estimate of solute movement in the soil fraction) increases with the ionic radius and decreases with increasing electronegativity; this explains the highest retention for Cd over Zn. Another explanation could be related to the amount of Zn and Cd in the soil and in the biochar used for this study. The Cd concentration in the soil and in the biochar was below the limit of detection, whereas the initial concentration of Zn in the soil was 7 mg kg-1 and SMB had a Zn concentration of 136 mg kg-1 (Tab. 2).

FIGURE 2 Sorption efficiency for A) cadmium (Cd) and B) zinc (Zn) for each dose of swine manure biochar (SMB) applied.

As higher concentrations of Zn solution were added to the soil, the binding sites for Zn in the soil or soil-SMB surface become less available, and more Zn was left in the solution.

Additionally, as shown in Table 2, SMB increased soil pH. An alkaline pH can promote the precipitation of metal hydroxides and, therefore, can decrease the mobility of metal ions in the soil profile (Pierangeli et al, 2009).

Conclusions and implications of the use of SMB to retain heavy metals in sandy soils

The results show the high capacity of SMB to help in Zn and Cd sorption in sandy soils, potentially avoiding problems with bioaccumulation, contamination, and toxicity via leaching and runoff.

The data adjusted best to the Langmuir isotherm, particularly for higher SMB doses, suggesting a monolayer sorption to the surface. Additionally, with SMB application a stronger adsorbate-adsorbent interaction was observed (higher KL) that could mean that SMB favors chemisorption over physisorption. On the other hand, soil without SMB showed weaker interactions with the metals.

Both SMB and the studied Ustoxic Quartzipsamment had a higher affinity towards Cd than Zn. This was related to the initial Zn content in both soil and SMB (7 and 136.25 mg kg-1, respectively), as well as higher electronegativity and ionic radius of Zn.

Despite the greater adsorptive capacity observed with 3% SMB, it is important to also consider the high cost of biochar application and look for the best cost/benefit relationship. In that regard, SMB applied at 0.75% proved to be effective for the retention of both metals with high efficiency. At this dose, the KF was about three times higher for Zn and Cd compared to the soil without the addition of SMB.

SMB addition to the soil increased the content of P, Na, K, TOC, NLC, LC, Zn, Mn, Cu and increased pH, making the soil more alkaline and more suitable for agriculture.

Although the results of this study are promising for Cd and Zn retention in sandy soils, more research is needed in the area. Particularly, more studies are necessary that focus on competition between Cd, Zn, and other heavy metals for the binding sites of SMB, metal desorption from the SMB-soil surface, and availability of the adsorbed metals to plants in order to evaluate if SMB addition is a good strategy for minimizing the risks associated with heavy metal pollution in sandy soils.