INTRODUCTION

Dental caries is one of the most prevalent chronic conditions in industrialized and non- industrialized countries. Its onset before six years of age (Early Childhood Caries, ECC) is recognized as a public health problem with oral consequences and impacts on children’s and their families’ quality of life.1,2,3 While there is evidence of an overall decline in the number and severity of carious lesions, time trends differ among countries. Preschoolers are the group that least benefits from measures intended to improve oral health, and the disease shows a skewed distribution in children living in the same area. These findings suggest that more actions are needed to deal with oral health inequalities.4,5

In Colombia, the latest National Oral Health Survey showed that dental caries affects 83% of three-year-old children, reaching 88.8% in five-year-old children when both cavitated and non-cavitated lesions are included.6 Moreover, dental caries, as one of the most prevalent chronic conditions in spite of the intensive preventive programs implemented in many countries, illustrates the limitations of such programs to deal with the disease burden and highlights the importance of additional information to design programs aimed at the early childhood according to the available evidence on control strategies.7

The studies on carious lesions distribution show that it is not uniform, suggesting the lack of random effect of contributing factors, as well as the presence of specific patterns in terms of teeth position and characteristics. Some authors suggest that there is no real right/left symmetry, although certain groups of teeth show similar susceptibility to lesion development.8 Caries patterns may vary in primary dentition, with the upper central incisors being the most affected teeth until the age of three,3,9 and second molar occlusal surfaces the most affected in five-year-old children.4,10,11 Another study showed no agerelated pattern, with the second molar being the most affected in preschool children.12

Recognizing specific caries patterns within a given population can be useful for oral health programs and warns clinicians about the early detection in preschool children. As non-invasive therapies have proven to be effective for caries prevention and for the management of initial lesions,13 caries patterns should be an important tool in changing invasive interventions into a more preventive, caries control approach, leading to better results for both individuals and populations.14

The aim of this study was to identify caries patterns in children aged 3 to 5 years living in a low to middle-low socioeconomic area in Medellin, Colombia, based on the ICDAS detection system, which records lesions at different severity stages.15

METHODS

A cross-sectional descriptive study was performed in children under six, attending preschool day care institutions located in a middle-low socioeconomic neighborhood from the northeastern area of Medellin. The study was carried out in four out of twelve private institutions with government funding and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad de Antioquia School of Dentistry. All children aged three, four and five years attending selected infant day-care centers were examined, prior presentation of an informed consent by the legal guardians of all participants in the study. A total of 548 available records from participants aged three to five were included for data processing and results.

Dental status was recorded according to International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS),16 including the modification suggested for this type of studies (ICDAS epi), merging ICDAS lesions level 1 with those of level 2.17 A calibrated dentist (intraexaminer Kappa 0.77 and interexaminer 0.71) registered caries lesions. Prior to clinical examination, an adult brushed each child’s teeth; cotton pellets were used to isolate the examination area, and dental surfaces were dried with gauze and air. Visual inspection of all present tooth surfaces was carried out, and a probe (Ball-tip Screening) was used when needed.

The presence of early childhood caries (ECC) and severe early childhood caries (S-ECC) was recorded according to the guidelines set forth by the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. ECC is defined as the presence of one or more primary teeth surfaces with caries (either cavitated or non-cavitated), filled or missing by caries, in children under six years of age. The severe form (S-ECC) is identified in the presence of any sign of caries on smooth surfaces in children under 3 years, when one or more smooth surfaces of the upper anterior primary teeth have cavitated lesions, are filled or lost due to caries, or when the number of carious, filled or lost surfaces by caries is ³4 at 3 years, ³5 at 4 years, and ³6 at 5 years of age.18

The collected data were analyzed in the IBM-SPSS® program, version 23.0. The percentages of affected teeth and tooth surfaces were estimated for the whole group and by single age, using frequency distribution. The percentage of surfaces affected by homologous teeth was calculated and differences were analyzed with the Epidat 3.1 software, using either the Chi square test or the Fisher’s exact test.

RESULTS

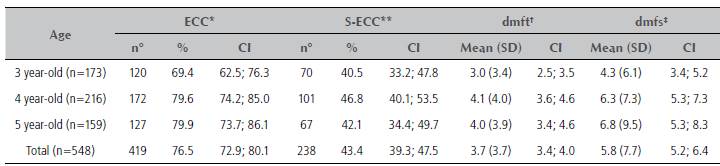

From a total of 548 children evaluated, 76.5% showed early childhood caries (ECC) and 43.4% had severe early childhood caries (S-ECC). In terms of dmft (including non-cavitated lesions), each child had an average of 3.7±3.7 teeth and 5.8±7.7 surfaces affected by dental caries, varying from 3.0±3.4 and 4.3±6.1 in 3-year-old children to 4.0±3.9 and 6.8±9.5 in 5-year-old children (Table 1).

Table 1 Distribution of children with ECC and S-ECC, mean dmft (SD) and mean dmfs (SD) by age

*: Early childhood caries. **: Severe early childhood caries. CI: Confidence Interval 95% †: decay, missing and filled teeth index. ‡: decay, missing and filled surfaces index

Source: by the authors

A total of 47,711 surfaces were examined, with the occlusal surface showing the highest values of caries lesions experience, varying from 17.7% to 36.1%. These were followed by upper smooth anterior surfaces affected in 0.2% to 17.2%. The lower smooth anterior surfaces showed the lowest values, from 0.0 to 6.8%, and as observed in upper anterior teeth, the lingual surfaces were the least affected. The individual teeth with the highest proportion of dental caries experience were 55 (42%), 75 (40%), 85 (38.3%) and 65 (37.1%); the lowest experience was found in 71 (1.8%), 81 (2.2%), 72 (2.9%) and 82 (4.6%). The proportions of dental caries experience by tooth and tooth surface are shown in Figure 1.

Source: by the authors

Figure 1 Dental caries experience (% affected) in primary teeth for 3- to 5-year-old children, by tooth and tooth surface levels.

The analysis of caries experience by tooth type showed that 39.5% of the upper second molars and 39.2% of the lower molars were affected, followed by upper first molars (29%) and upper central incisors (23.2%). The lowest values were observed in lower central and lateral incisors, with 2.0% and 3.8% respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of caries presence per tooth surface in homologous teeth, showing predominance of occlusal lesions in primary molars and buccal surfaces in lateral upper incisors. In the upper central incisors, lesions appear in a similar proportion in the bucal, mesial and lingual surfaces.

Source: by the author

Figure 2 Distribution of affected teeth surfaces per tooth type (% with caries experience).

Table 2 shows the caries pattern for each homologous tooth in terms of the most affected surfaces, comparing each surface, referred to as “caries attack rates” by Gizani et al.19 Each individual surface was compared with others by Chi square test or Fisher’s exact test. Statistical significance was found when the occlusal surface is compared with the rest of upper and lower molar surfaces. It was also found in anterior teeth, when the labial or facial surfaces were compared to lingual surfaces, with the exception of the upper central incisors.

Table 2 Comparison of caries experience among homologous teeth surfaces (D: distal, B: labial or facial, M: mesial, L: lingual, O: occlusal)

| Age | Tooth type | Caries pattern | D-B | D-M | D-L | D-O | B-M | B-L | B-O | M-L | M-O | L-O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 to 5 years | 51/61 | B>M>L>D | *** | *** | *** | ns | ns | * | ||||

| 71/81 | B>M>L>D | *** | ns | ns | ** | *** | ns | |||||

| 52/62 | B>M>L>D | * | * | *** | *** | *** | ns | |||||

| 72/82 | B>M>L>D | *** | ** | ns | * | *** | * | |||||

| 53/63 | B>L>D>M | *** | * | ns | *** | *** | ** | |||||

| 73/83 | B>M>L>D | *** | * | ns | *** | *** | ns | |||||

| 54/64 | O>B>D>M>L | ns | ns | ns | *** | ns | * | *** | ns | *** | *** | |

| 74/84 | O>B>L>D>M | *** | ** | ns | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** | *** | |

| 55/65 | O>L>B>M>D | *** | ns | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| 75/85 | O>B>L>M>D | *** | ns | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| 3 years | 51/61 | B>M>L>D | *** | * | ns | ns | * | ns | ||||

| 71/81 | B | ** | † | † | * | * | † | |||||

| 52/62 | B>M>L>D | *** | *** | * | ns | * | ns | |||||

| 72/82 | B>M | ** | ns | † | ns | ** | ns | |||||

| 53/63 | B>L | *** | † | ns | *** | ** | ns | |||||

| 73/83 | B>M | *** | ns | † | ** | *** | ns | |||||

| 54/64 | O>B>M>L>D | *** | ns | ns | *** | ns | ns | *** | ns | *** | *** | |

| 74/84 | O>B>L>D>M | *** | ns | ns | *** | *** | *** | ** | ns | *** | *** | |

| 55/65 | O>L>B>D>M | ns | ns | *** | *** | * | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| 75/85 | O>B>L>D>M | *** | ns | ns | *** | *** | *** | * | * | *** | *** | |

| 4 years | 51/61 | B=M>L>D | *** | *** | *** | ns | ns | ns | ||||

| 71/81 | B>M>L=D | * | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |||||

| 52/62 | B>M>L>D | *** | *** | ** | *** | *** | ns | |||||

| 72/82 | B>M>L=D | *** | * | ns | ns | *** | ns | |||||

| 53/63 | B>L>D | *** | ns | ns | *** | *** | ns | |||||

| 73/83 | B>M>L>D | *** | ns | ns | *** | *** | ns | |||||

| 54/64 | O>B>M>D>L | ns | ns | ns | *** | ns | ns | *** | ns | *** | *** | |

| 74/84 | O>B>D>L>M | *** | ns | ns | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | *** | *** | |

| 55/65 | O>L>B>D>M | ** | ns | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| 75/85 | O>B>L>M>D | *** | ns | *** | *** | *** | *** | * | ** | *** | *** | |

| 5 years | 51/61 | B=L>M>D | * | ns | * | ns | ns | ns | ||||

| 71/81 | B>L>M | * | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |||||

| 52/62 | B>L>M>D | *** | ** | ** | * | * | ns | |||||

| 72/82 | B>M>L>D | * | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |||||

| 53/63 | B>L>D>M | *** | ns | ns | *** | *** | ns | |||||

| 73/83 | B>M>L | *** | ns | ns | *** | *** | ns | |||||

| 54/64 | O>D>B>L>M | ns | ns | ns | *** | ns | ns | *** | ns | *** | *** | |

| 74/84 | O>B>L>D>M | * | * | ns | *** | *** | ns | *** | * | *** | *** | |

| 55/65 | O>L>B>M>D | ns | ns | *** | *** | ns | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| 75/85 | O>B>L>M>D | *** | ns | ** | *** | *** | *** | ** | ** | *** | *** |

*p value < 0.05, **<0.01, ***<0.001 (chi square test/Fisher’s test) ns: no significance, †: caries free surface Source: by the authors

DISCUSSION

The present study shows a specific pattern of dental caries in preschool children living in an urban area, belonging to a high prevalent group where severe forms of Early Childhood Caries affects more than 40% of examined children. Even though caries lesions are present in all teeth, with the exception of a few surfaces from anterior lower teeth in the entire group, distribution is not uniform by tooth type, showing that caries lesions are not evenly distributed.

The most affected teeth in the three to five-year-old group were second molars, followed by first lower molars and upper central incisors. These findings are similar to those by Sowole et al12 and Gizzani et al19 in terms of anterior primary teeth being less affected than posterior teeth, regardless of caries levels. But there is a difference with Gizzani et al, who report first lower molar as the most affected posterior teeth, followed by central incisor in a group of 2-6-years-old; this also differs from the findings by Ferro et al,11 who reported that mandibular molars were the most commonly affected teeth in a sample of five-year-old children.

The variations among studies could be explained as an effect of grouping children by ages, as Vanobbergen et al14 reports upper central incisors showing the highest caries experience prevalence in the 3-year- old group; trend changing for the 5- and 7-year-old kids, in which the highest caries prevalence level was observed in the mandibular molars. There could also be population differences. As Sowole et al12 report, it appears to be a non-significant age-related caries distribution pattern, based on clinical examinations in preschool children, concluding that neither rampant caries nor simple caries prevalence appear to be age dependent. Do1 states that there are significant variations in levels of caries experience as well as in time-trends of caries experience among populations with different levels of social and economic development.

In this study, the most affected teeth among 3-year-old children were the upper second molars and lower second molars, followed by first lower molars, first upper molars and central upper incisors. For the 4-year- old children, second molars remain the most affected teeth, followed by first lower molars, but upper central incisors show higher proportions of caries lesions than upper first molars. By age 5, second lower molars appear as the most affected tooth type, followed by second upper molars, first lower molars, first upper molars and upper central incisors.

As in other studies, caries prevalence increases with age, showing a cumulative effect from 3 to 5 years, but no conclusions could be stated about lesion progression and changing patterns by age as these are cross-sectional data. Cohort studies or cross- sectional studies including larger samples could provide valuable information on specific patterns by age, guiding clinicians and program leaders in the formulation of regular screenings for each age group.

In analyzing available data by tooth surface, not all teeth show the same susceptibility. The lingual anterior surfaces were the least frequently affected in the anterior region, and the occlusal were the most affected molar teeth surfaces. These findings are similar to those reported in other studies dealing with either low caries or high caries experience populations.9,14,19,20 While some authors refer to specific surface involvement as “caries attack rates”,19 there is no evidence of time sequence of lesions, but this is an important information about the distribution of caries presence according to tooth surface by tooth type. For all posterior teeth, regardless of age groups, the most affected surfaces are the occlusal ones, showing statistically significant differences between the occlusal surface and the others, as compared individually. For anterior teeth, the most affected surface is the labial or facial, but consistent statistically significant differences are only observed between buccal and lingual surfaces. A limitation of the present study is that it did not evaluate symmetry (the spatial distribution between the right and left homologous teeth) as showed by Vanobbergen et al14 because the total number of teeth in each group would not be enough.

While information about occlusal susceptibility is highly relevant in term of screening focus, treatment needs and preventive strategies, it could be inadvisable to wait until molar eruption-occurring later during early childhood-for risk assessment and early childhood preventive programs based on this data only. Dental teams and children’s health providers are increasingly aware of the need of implementing preventive measures from the first year of life. Non-dental healthcare providers could be of great help by identifying any single lesion, irrespective of its location, and referring the child for treatment and establishment of a dental home.21,22 An oral check-up after the first tooth eruption should be integrated into the existing health programs like vaccinations and general medical check-ups.2

Many attempts are made to deal with caries burden. For Seiham,23 caries prevention is preferable to treatment, but the high levels of caries worldwide suggest that current preventive approaches are not working. As stated in Brussels by the EAPD13 and Pitts et al,24 non-invasive therapies have proven to be effective for caries prevention and the management of pre-cavitated carious lesions. Knowing the most commonly involved teeth and surfaces in a specific population is key to guide dental screenings aimed to identify early signs and to promote adequate oral hygiene practices and fluoride use to stop lesions, according to the caries control concept.25

CONCLUSION

A group of children living in a high prevalent ECC middle-low-income community shows specific patterns of caries lesion distribution, with primary molars being the most commonly affected, especially the occlusal surfaces, followed by the upper central incisors. These data are useful for programs aimed at families and communities to detect early sings of dental caries, and to guide dental care services in timely diagnosis and lesion progression strategies.