Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Innovar

Print version ISSN 0121-5051

Innovar vol.21 no.42 Bogotá Oct./Dec. 2011

Nuno Ferreira da Cruz* & Rui Cunha Marques**

* MSc (c), Researcher at the Center for Management Studies of IST (CEG-IST), Technical University of Lisbon, Portugal. E-mail: nunocruz@ist.utl.pt

** PhD, Professor at Instituto Superior Técnico, Researcher at the Center for Management Studies of IST (CEG-IST), Technical University of Lisbon, Portugal. E-mail: rui.marques@ist.utl.pt

Submitted: August 2010 Accepted: May 2011

Abstract:

The growing budget restrictions and decentralization processes that local governments face nowadays are threatening the sustainability of local public services. To overcome this problem, local decision-makers around the world have been developing ambiguous reforms, leading to various governance models. Since these services are essential for citizens' welfare, it is crucial to determine whether or not these models have been effective and useful to cope with this state of affairs. To offer extra leverage to key projects, the European governments have been resorting to public-private partnerships (PPPs). One of the visible trends, which lacks further research, has been the use of mixed public-private companies (institutionalized PPPs). Although it is recognized that this solution can be interesting for both public and private sides, it has some particular features that can avert the aimed goals. This paper provides a literature review on mixed companies encompassing theoretical, legal and operational aspects. It also focuses on regulation by contract, referring to a particular Portuguese case study in the water sector and explaining how the municipality handled risk allocation and regulated the access to the market of private investors. Finally, it discusses the need for external regulation and makes suggestions on how these processes should be managed right from the bidding stage.

Keywords:

Local public services, mixed companies, PPP, regulation by contract.

Resumen:

La creciente restricción presupuestal y los procesos de descentralización que actualmente enfrentan los municipios amenazan la sostenibilidad de los servicios públicos locales. Para superar este problema, las autoridades locales de cada país han venido desarrollando reformas ambiguas que han generado la aparición de diferentes modelos de gobernabilidad. Dado que estos servicios son esenciales para el bienestar de los ciudadanos, es crucial determinar si estos modelos son eficaces y apropiados para lidiar con tales condiciones. Para ofrecer un apoyo adicional a proyectos clave en esta materia, los gobiernos europeos han recurrido a asociaciones público-privadas (APP). Una de las tendencias más visibles y que ha sido muy poco investigada, es la del uso de empresas de capital mixto (APP ya institucionalizadas). A pesar de que esta alternativa puede ser atractiva para ambos sectores (público y privado), sus características particulares se opondrían a los objetivos trazados.

Así, este artículo presenta una revisión de la literatura sobre empresas mixtas, abarcando aspectos teóricos, legales y operacionales. Las cuestiones de regulación por contrato también son evaluadas e ilustradas con un estudio de caso en el sector del agua de Portugal. El estudio analiza cómo el municipio maneja la distribución de riesgos y regula el acceso al mercado de inversionistas privados. Al final, se discute la necesidad de una regulación externa y se hacen algunas sugerencias sobre cómo un proceso de constitución de una APP debe manejarse, incluso desde la etapa de licitación.

Palabras clave:

empresas mixtas, APP, regulación por contrato, servicios públicos locales.

Résumé :

La restriction croissante de budget et les processus de décentralisation affrontés actuellement par les communes menacent la durabilité des services publics locaux, Pour résoudre ce problème, les autorités locales de chaque pays ont développé des reformes ambigües entraînant l'apparition de différents modèles de gouvernance. Étant donné que ces services sont essentiels pour le bien-être des citoyens, il est essentiel de déterminer si ces modèles sont efficaces et appropriés pour affronter de telles conditions. Pour offrir un appui supplémentaire aux projets clefs dans ce domaine, les gouvernements européens ont eu recours à des associations publiques-privées (APP). Une des tendances les plus visibles, sur laquelle très peu de recherches ont été effectuées, consiste en l'utilisation d'entreprises de capital mixte (APP déjà institutionnalisées). Bien que cette alternative soit attractive pour les deux secteurs (public et privé), ses caractéristiques particulières s'opposent aux objectifs proposés. Cet article présente donc une révision des publications concernant les entreprises mixtes, recouvrant les aspects théoriques, légaux et opérationnels. Le thème de la régulation par contrat est également évalué et illustré par une étude de cas dans le secteur de l'eau au Portugal. Cette étude analyse la gestion par la commune de la distribution des risques et du contrôle de l'accès au marché d'investissements privés. Finalement, la nécessité d'une réglementation externe est discutée et certaines propositions sont élaborées concernant la gestion du processus de constitution d'une APP, l'étape d'appel d'offre y compris.

Mots-clefs :

entreprises mixtes, APP, régulation par contrat, services publics locaux

Resumo:

As crescentes restrições orçamentais e os processos de descentralização que os municípios enfrentam atualmente têm vindo a ameaçar a sustentabilidade dos serviços públicos locais. Para ultrapassar este problema, os decisores locais de cada país desenvolveram reformas ambíguas que levaram ao aparecimento de diferentes modelos de governança. Dado que estes serviços são essenciais para o bem-estar dos cidadãos, é crucial determinar se estes modelos são eficazes e apropriados para lidar com as novas condicionantes. Para alavancar novos projetos, os governos Europeus têm recorrido a parcerias público-privadas (PPPs). Uma das novas tendências, ainda muito pouco investigada, tem sido o uso de empresas de capital misto (PPPs do tipo institucional). Ainda que esta solução possa ser interessante para ambos os setores, público e privado, o modelo apresenta algumas particularidades que podem desvirtuar os objetivos iniciais. Este artigo apresenta uma revisão da literatura sobre empresas mistas, englobando aspetos teóricos, legais e operacionais. As questões da regulação por contrato também são avaliadas e ilustradas com um estudo de caso no setor da água em Portugal. No estudo se analisa a forma como o município lidou com a alocação de riscos e regulou acesso ao mercado dos investidores privados. Por fim, se discute a necessidade de regulação externa e são feitas algumas sugestões sobre como o processo de constituição de uma PPP deve ser gerido desde a fase de concurso público.

Palavras-chave:

empresas mistas; PPP; regulação por contrato; serviços públicos locais.

The local administration is a subdivision of the public administration and works as the link between the central State and the citizens (Cruz and Marques, 2011). In order to keep up with the Euro convergence criteria and stability rules, all Member States are facing important financial limitations which also imply growing budget restrictions to local government bodies. However, this is just part of the problem. In fact, the responsibilities of local and regional governments are continuously increasing, going much further than their traditional scope of competences. Portuguese local governments are traditionally unfamiliar to areas such as health and education, but with the decentralization tendencies observed and the transference of responsibilities and duties performed by the central administration, it is mainly up to the municipalities to provide a great amount of public services. These decentralization processes can be observed quite a lot around the world, representing new challenges to this field of research (Devas and Delay, 2006).

In the quest for the "best way" of providing local public services, municipal decision-makers should craft governance models that can efficiently combine the population needs and the resources available. Within this scope, the New Public Management (NPM) paradigm, which comprises a portfolio of prescriptions implying the rearrangement of traditional administrative structures, has been influencing several governments around the world (Hood, 1991; Ridley, 1996). Corporatization of the services is one of the possible policy decisions and some authors argue that, with this process, outputs and revenues as well as cost-efficiency and employees' productivity are expected to increase (Bilodeau et al., 2007). Nevertheless, while the corporatization of local public services is getting popular across the globe, there is still too little empirical evidence about its actual impacts on municipal performance (Boyne, 2003).

The NPM, defined by Osborne and Gaebler (1993) as "reinventing government", has been implemented in practical terms in several countries, ensuing different administrative structures that represent an alternative to traditional bureaucratic management. As shown by Greve et al. (1999) and Vining and Weimer (2006), the options encompass public capital companies (100% public or mixed companies) as well as outsourcing and full privatization. No matter which structure provides local services (municipal companies, municipal services with or without autonomy, concessions or others) the promotion of competition regarding both economic and social performance is essential (Moore et al., 2005).

As if this state of affairs was not complex enough by itself, the current capital crisis tends to make things a bit harder. While central administrations slip the public debt limits, also local governments are forced to manage with more demanding budget restrictions. Hence, local governments have been turning themselves to other ways of providing services, resorting to the help of private initiatives through public-private partnerships (PPP). In the present article, these subjects are thoroughly addressed and illustrated by a detailed analysis of a particular contract involving a mixed company (institutionalized PPP or iPPP) in charge of water supply in a Portuguese municipality. This analysis is made as an attempt to learn if, facing this complex scenario, mixed companies represent an effective tool for local governments, and therefore a model with capabilities for the future.

The current article is organized as follows. After this introduction, the second section provides a scrutiny of the international scene regarding the provision of local public services by means of mixed companies. The third section presents a full picture of the reality observed in the Portuguese municipalities and of the legal framework supporting these new models. The fourth section contains the case study analysis and the concluding remarks are drawn in the fifth and final section.

Definition

As it is laid down in the Green Paper on PPPs by the European Commission (see also Essig and Batran, 2005) there are two different types of PPP arrangements: The ones based on a purely contractual relationship (e.g. concessions) and the more institutionalized ones, where both public and private sectors gather and cooperate in a distinct entity. Recent literature has shown that the use of PPPs to deliver public infrastructure services raises special concerns (e.g. see McQuaid and Scherrer, 2010, and Hodge and Greve, 2010). Indeed, the long-term character of the arrangements (a requirement of this type of sunk investments) makes the contracts incomplete due to problems of bounded rationality (Williamson, 1985). Klein et al. (1996) estimate that transaction costs in "private infrastructure projects" are usually about 3 to 5% in well-developed policy environments, while they may be 10 to 12% in other conditions. Hence, the idea of crafting governance structures that (in theory) are able to cope with the problems of incomplete contracts and to solve disputes from within the companies seems to be a noble intent. The (partial) public ownership should reduce asymmetric information (a serious shortcoming of PPPs) and allow local governments to cope with principal-agent problems through "internal regulation". Thus, the iPPP model appears as an alternative both to direct public production and to the delegation of utility services to private firms through concession contracts (Marra, 2007).

Usually, corporatization is the step preceding the creation of a mixed company. This process differs from the "agencification" concept (Pollitt et al., 2005) and it has been profoundly studied over the past two decades. However, the joint ventures between public and private sectors within these organizations as a form of PPP and their impact in society still lacks further research and gathering of empirical evidence. Besides the creation of a new public company and the subsequent participation of a private entity (by acquiring shares through a public tender), there is another possible way for municipalities to be partners with private investors within distinct entities; the government can directly acquire shares in an existing private company (or indirectly through other companies owned by the local government). However, the cases where local governments buy a participation in existing companies can be trickier and the motivations for doing so may differ from the process mentioned previously.

In most cases, local governments retain the dominant influence in mixed companies responsible for delivering local public infrastructure. In practice, this is accomplished by having the majority of the shares (at least 51%) on the public sector side, which should be sufficient to keep the entities at arm's length and, at the same time, allow for the pursuit of social goals. Different ownership structures usually denote objectives other than managing general-interest services.

Mixed companies in charge of delivering public infrastructure have special features that deserve to be pointed out.

For instance, the results attained by Sathye (2005) showing that the gradual privatization of Indian banks (using partial privatization) had overall positive effects on performance, or the research carried out by Mok and Chau (2003) on the reform of state-owned enterprises that took place in China (several general-purpose firms were partially sold to private investors) are not necessarily comparable with utility services that are public monopolies (e.g. water supply).

The literature depicts some intuitive results on mixed companies operating in several sectors. Chiu (2003) and Chiu et al. (2002) argue that if the "owner conflict" level is low, public companies have higher cost inefficiency, followed by mixed and then private companies (yet, it is possible that difficulties in the relationships among shareholders can turn mixed companies to the most inefficient). However, higher cost inefficiencies might be necessary to achieve certain social targets. Furthermore, evidence from the partial privatization of the Nippon Telegraph and Telephone corporation shows that the apparent improvements in productivity were mainly due to staff reductions and that the creation of the mixed company failed to comply with the objective of reducing costs (which has ultimately resulted in more expensive services for the consumers; Sueyoshi, 1998). It seems that, more than the ownership of the companies in charge of delivering an infrastructure service, the institutional and regulatory framework must also be addressed in every analysis (Cambini, 2010). Frequently, mixed companies in charge of delivering local infrastructure services are unlisted and the partners own nontradable shares (the intuitive results on public ownership should then be reconsidered).

The bureaucratic models of service delivery do not always provide the flexibility sought by local politicians who sometimes consider them to be inefficient or unable to provide value-for-money (Shleifer, 1998). To avoid a "standar" privatization, several local authorities are looking at the mixed company model as a way of retaining the dominant influence (e.g. see Verdier et al., 2004). Indeed, with iPPP arrangements, local decision-makers try to craft an "alliance model" that allows them to cope with complexity (Edelenbos and Teisman, 2008). The problem is that, because local governments assume the role of both regulator and regulated (as a shareholder of the regulated firm), conflicts of interest are more likely to appear with this governance model (Schaeffer and Loveridge, 2002).

The NPM movement involved private providers in local public services delivery by means of outsourcing or full privatization processes. This paradigm blurred the boundaries between the public and private sectors and eventually resulted in some recent experiences with mixed companies. Despite the fact that most literature refers to the challenge of deciding between in-house provision or contracting out part of the service (lease) or all of it (concession or full privatization) to the private sector, one can begin to find some research on mixed public-private companies at the local level.

An international perspective

Eckel and Vining (1982) carried out the first efforts to provide an answer to several questions regarding mixed companies. In these early approaches, the authors suggest that one of the obvious advantages of joint ownership over totally public ownership is the increased pressure for financial or commercial viability. Furthermore, it is said that pure public production can cause an inefficient balance between social goals and profits and that government monitoring is then required. This monitoring can be complex because social output can be difficult to measure; besides, it is costly and consumes resources. However, partial private ownership should lessen the need for monitoring the profitability of the companies (or the economic sustainability) and this is appealing to governments since it might reduce monitoring costs. At that time, Eckel and Vining (1982) argued that jointly-owned firms tend to be more efficient than 100% public firms (however, less than totally private ones, from a strictly financial perspective). Currently, despite the very little empirical evidence that supports this claim (e.g. Raffiee et al., 1992), we know that the conclusions about the efficiency of public and private sectors entities are hazy (Bel et al., 2010).

Later on, Boardman et al. (1986) declared that the true test of mixed companies is how well they can achieve an ideal combination of (financial) efficiency and social objectives. Also, in this research the authors pointed out that it is possible to achieve social gains at a lower cost by regulation or taxation rather than by government participation within the companies. However, mixed companies may be used for local or regional development, as government participation can influence the location of firms. In theory, joint ownership might offer an optimal combination mitigating the disadvantages of pure public ownership and full privatization (Schmitz, 2000).

More recently Vining and Boardman (2006) state that mixed companies can result in "the worst of both worlds". The authors suggest that the appropriate test of success for this type of ventures is whether or not they have lower total social costs (including production costs and all the transaction costs and externalities). Basing the conclusions on ten Canadian case-studies, the research shows that the potential benefits are often outweighed by high contracting costs due to opportunism (these costs increase when the operation is complex and the revenue is uncertain or, in other words, when the risk is higher).

In Spain mixed public-private firms are a relatively common practice in the provision of local public services. Bel and Fageda (2010) explain that private partners tend to be large firms with extensive know-how that conduct dayto- day operations, while local governments retain some degree of control over the firm. These authors argue that mixed companies emerge as the middle term between pure public and private production and that they are founded on cost concerns and financial constraints of local governments as well as private interests. These factors yield contradictory pressures which increase the complexity of the process of choosing between mixed companies or other "pure" production models. For Spanish local governments the mixed firm option seems to be non-ideological, where it is also possible to discern some interesting relationships (Bel and Fageda, 2010): Municipalities that cooperate at a regional level are more likely to use mixed firms; there is an optimal municipality size for partial privatization processes; mixed companies are more likely to be the preferred mode when the specific transaction costs of the service are high and industrial interests are weaker; finally, when the fiscal burden on a specific local government is high, the probability of having mixed companies providing public services is also higher (since the option of pure public production is limited by financial constraints).

French local authorities can choose between several organizational models for the provision of public services. The mixed company model (société d'économie mixte) in this country has an interesting feature: The majority of the capital share is public and may vary from 51% up to 85% of the shares. Since 1993, the private partners have to be selected through a competitive tendering process; however, local governments have freedom to include subjective criteria and the process comprises a mix between traditional competitive bidding and negotiation procedures (Amaral et al., 2009). Still, local decision-makers are legally required to justify their decisions (even though the reports are not publicly available). In France, local mixed companies operate under contractual frameworks similar to the ones applicable to fully private operators (Lobina and Hall, 2007).

Italy has gone through some significant changes regarding the provision of local public services; starting in the 1990s and with the 2002 Financial Law being an important step in a widespread reform of the whole sector, the main idea was to liberalize the market and award the services via competitive tendering. A recent study reports that 14% of local public services in Italy are delivered through mixed companies (Bognetti and Robotti, 2007). The new Italian rules allow for the creation of these companies with either public or private majority; however, in all cases, a public tender procedure is compulsory. Furthermore, Bognetti and Robotti (2007) make several interesting remarks concerning Italian mixed companies providing local public services:

- Mixed companies allow for the exploitation of economies of scale and of scope, without the loss of control of the leadership by local governments;

- Mixed companies have better flexibility (e.g. in Italy, they are often seen acting outside their own jurisdictions);

- Mixed companies seem to be preferable to other models of multi-service provision.

Also in Italy, Marra (2007) concluded that production costs and information costs can be lower than in the cases of in-house provision or concession to totally private companies. Nevertheless, it is stated that to function properly, the information in these companies needs to flow from the technological management through the board of directors and the external regulator (by implementing a sort of "internal regulation"). This can only be achieved if public representatives on the board hold high expertise and act in complete independence.

In Germany there are also public utilities where private investors participate in the firm's share capital (usually a minority stake); however, these mixed companies (Kooperationsgesellschaft) are still very few when compared with other governance models in operation. Besides, there are some indications for this country that, at least regarding innovation, the organizational form is irrelevant (Tauchmann et al., 2009). On the other hand, it is in Germany where we can find the biggest mixed company providing local public services in Europe: Berliner Wasserbetriebe. The partial privatization of this company (provider of water services) was carried out in 1999 and the contract was signed for a period of 25 years between the City of Berlin (50.1% of the shares) and the international companies RWE and Veolia together (24.95% of the shares each). The effects of this choice are hazy (Oelmann et al., 2009); the partnership has definitively been positive for both the City of Berlin and the private shareholders. Indeed, Berliner Wasserbetriebe has had overwhelming profits and the annual payments to the City of Berlin amount to 208.2 million Euros (in average, since 2000) which is much more then when it was under full ownership (64.6 million Euros for 1996 to 1998). Furthermore, concerning the last five years of activity, the average return on invested capital for private partners was around 10.3% (before taxes) which seems rather high. However, these benefits have not been fully passed on to consumers. Despite the fact that the quality of service has risen to impressive levels, after the partial privatization the changes in water prices and in wastewater charges continued to be nearly the double of the German average (Oelmann et al., 2009). In addition, the current prices for wastewater services are very high (much higher than the national average). Clearly, mixed companies nowadays play a significant role in the provision of local public services in the EU (Warner and Bel, 2008).

In developing countries, the first to shift from the traditional PPP schemes towards the use of the mixed company model was Colombia (Marin, 2009). In this country the first contracts following the iPPP model were awarded in 1996- 98 for water utilities. In line with the Spanish approach, the municipalities held the majority of the shares while the management was fully delegated to private investors. The performance of this model has been rather satisfactory in Colombia, especially in the quality of service dimension; in fact, the coverage increased substantially for municipalities with mixed-ownership utilities, both for drinking water supply and wastewater services (Marin, 2009). Besides Colombia, mixed companies are also operating in the water sector in other countries of Latin America (e.g. Havana in Cuba and Saltillo in Mexico) as well as in the Czech Republic and Hungary in Eastern Europe (Marin, 2009).

The arguments for and against the outsourcing of public services are not new; some argue that it adversely affects workers' employment conditions (Quiggin, 2002) and others that it may lead to quality reduction (Hart et al., 1997). Taking this into account, the design to match both social and economic concerns (public and private concerns) seems, a priori, to gain some strength and plausibility. Nevertheless, the accomplishment of this objective by opting for mixed companies still lacks proof and empirical evidence. This paper intends to positively contribute to the literature on the use of iPPP arrangements for the delivery of local infrastructure services.

Decision drivers

As Figure 1 shows, in Portugal the level of transference of responsibilities to local governments (decentralization of services) is not as high as the ones observed in most OECD countries. Both the revenues and the expenditures of local governments are, in percentage, lower than in other countries. This means that the process is still at an early stage for this country and that several measures should be put into practice to reduce the presence of the central state in the economy.

While a large proportion of the resources of the Portuguese central government are devoted to health and education, local governments are more heavily involved in providing the following services: environmental protection, recreation, housing and community amenities. General public services (transportation, drinking water supply, etc.) represent a big slice in the expenditures of both central and local governments (OECD, 2009). The budget restrictions, debt limitations, lack of resources and need for more capacity to invest in new infrastructures are threatening local and regional development. Consequently, the models of service provision adopted need to be innovative and highly efficient and public services with economic interest will have to fully recover the cost of the services supplied.

The partial privatization processes experienced worldwide (especially in transition economies) have often occurred with the state retaining a non-controlling ownership share. There are some cases in China but a similar phenomenon was felt in many Eastern Europe countries (Maw, 2002). In the Portuguese local administration this panorama is slightly different. Portugal, as all EU countries, is a market economy governed by liberal principles. Hence, the legitimacy for the entrepreneurial activity of local governments is limited (in order to ensure the full and open competition). On the other hand, the municipalities have the obligation and responsibility to provide several public services and they may choose to do it via mixed companies. In this case, local governments create municipal companies (which can be 100% public or iPPP arrangements). In Portugal, the concept of municipal company implies that the municipality has a dominant influence (direct or indirect). This can be attained either by owning the majority of shares (which is what happens in practice) or by safeguarding the right to nominate or dismiss the majority of the elements of the board of directors or of the supervisory board (Cruz and Marques, 2011). Mixed companies operate under private commercial law which allows them to have some flexibility regarding human resources management. Indeed, new employees can be hired under private sector labor law. However, mixed companies usually become responsible for services that were previously managed in-house by public servants and they have to incorporate these employees in their workforce (legally, each worker can choose to keep the same status or change its contract of employment).

In the process of partial privatization, a municipality (or an association of municipalities for intermunicipal companies) and a private firm ensue a long-term contract through the jointly-owned company. Taking into account the features of iPPP arrangements and the Portuguese (and European) regulatory framework one might infer that, in general, the main reasons to provide a local public service by means of a mixed (municipal) company are the following:

(1) Debt ceiling

This is seen as the major reason for public sector entities to rely on PPP models (either iPPP or cPPP agreements). The Portuguese Local Budget Law imposes a debt limit of 125% of the total revenue corresponding to the previous year. Local decision-makers turn themselves to PPP arrangements so that municipalities can undertake "indirect loans" (according to EUROSTAT, if the private partner is responsible for, at least, two types of risks, then the debt associated with the PPP do not enter public accounts). However, for local iPPP contracts, if there is no adequate risk sharing and if the mixed companies fail to attain balanced accounts, the contracted loans should add up to the debt limits imposed to municipalities (as stated in the Portuguese law). Still, the possibility of acting without so much direct budget restrictions may give a bias in favor of the decision to create a mixed company (sometimes, it may be the only possible way that municipalities have to provide a service without disrespecting the debt limits).

(2) Control

With the iPPP option, the municipalities retain control of a public service that needs to stay public. Local governments acknowledge the flexibility that mixed companies provide them. On the one hand, they do not give up the services which, in the case of services of general economic interest, have the potential to generate important revenue for the municipalities. On the other hand, local governments may see this as an option that guarantees the commitment of the project company with public service obligations (local governments are held accountable for the "social performance" of the services in every election). Theoretically, local decision-makers may feel that the mixed company model can reconcile liberalization with public interest and public service obligations and somehow reduce the problems and uncertainties involved with long-term incomplete contracts. For effective control and decisional power to exist in the company, the ownership needs to be sufficiently concentrated. The local government does not act just as a major institutional shareholder; it exerts an effective controlling authority.

(3) Know-how

The creation of mixed companies is often founded on cost concerns (Bel and Fageda, 2010), an area where the private sector should perform well if previously submitted to market pressures (although it is not clear that actual cost efficiency is achieved in private utilities; Bel et al., 2010). The objective is to produce a service that achieves the breakeven by reducing the operating costs. To do this local governments rely on the private partner's expertise. However, the search for this know-how and the economic and financial concerns come with an additional aspect: the requirement to reward the private partner. So, we are in a situation where the public sector opts to call for the private sector assistance, even though it has the potential to be a more expensive model (comparing with the ideal 100% public provision model and its theoretical capabilities where there is no need to pay off a private partner). Can this be seen as a "certificate of incompetence" of the public sector concerning its managerial capacity? Probably not, as this is a complex problem where economic concerns are bundled with social concerns.

(4) Up-front payment

A lot of municipalities provide local public services in-house and revenues from customers are often less than costs. To turn these services (in deficit) into profitable activities would be an ideal target for local governments in order to support other investments. The Portuguese law does not preclude profit for municipal companies; this simply cannot be the primary objective of these entities. However, in the mixed company case, the municipalities generally ask for an up-front single payment (usually a generous sum) working as a "buy in" that the private partner has to pay to earn the right to manage the service (and extract a rent from it). This is also an attractive scenario for local decisionmakers; obviously this motivation has a political dimension as these takings can be used to lessen some other political struggles. However this revenue should never be obtained at the expense of economic efficiency. Theoretically, the extra costs involved (including contracting costs and the remuneration of the private investor) must be outweighed by the efficiency gains expected from having the participation of the private sector in the management of the services (and the hypothetical added pressure for financial viability; Eckel and Vining, 1982).

(5) Quality

NPM followers and several local decision-makers state that traditional bureaucratic structures are no longer able to provide effective services (Cruz and Marques, 2011). These actors argue that due to the expansion of infrastructure networks, new quality thresholds imposed by customers and new (and more demanding) regulations require different models. The mixed company model can provide the necessary dynamism (private duty) and, at the same time, guarantee the suitable quality levels (public duty). It is the objective of this governance model to maximize public welfare, attaining it from the conflict between the strategic autonomy of the company and its political subordination.

Legal and regulatory framework

The EU "light" legislation on public procurement and concessions to iPPP is addressed in the Communication C(2007)6661. This document tackles the questions related to the creation process, the selection of private partners, and the management of the company. It is stated that the "simple capital injections made by private investors into publicly-owned companies, do not constitute iPPP"; the private input, apart from that, implies an active participation in the operation of the contracts awarded and/or on the management of the project company. Furthermore, to comply with the principles of Community law, the private partner must be selected via a transparent, non-discriminatory and competitive procedure. In the Commission's view, the contracting entity (in this case, the municipality) should include in the contractual documents the following basic information: the public contract to be awarded to the PPP entity, the statutes, and the shareholders' agreement. Furthermore, the tender call notice should include information on the intended duration of the iPPP. Mixed companies are excluded from being regarded as in-house structures on behalf of the contracting entities which form part of them. Hence, procurement rules must be fulfilled when awarding new contracts or concessions (different from the ones subjected to the tender procedure). All the information necessary to ensure fair and effective competition for the market should be provided.

In Portugal, the legal regime for the local business sector brought some modernity by setting a lot of regulations in accordance with the private sector law. This legislation allows for the creation of municipal, intermunicipal and metropolitan companies and offers local officials additional discretion in personnel and financial management by transferring in-house service production to new and autonomous corporations. Furthermore, this diploma inhibits the creation of companies with a dominant mercantile purpose or that simply carry out administrative activities. The object of municipal companies must correspond to one of the following dimensions:

- Provision of services of general interest (with economic interest);

- Local and regional development promotion (services of general interest without economic interest);

- Concessions management.

Municipal companies included in the first dimension should only charge enough to accomplish breakeven, while entities carrying out activities without economic interest should strive to breakeven. The law also compels municipal companies to submit themselves to the powers of sectorspecific regulators when operating in regulated sectors.

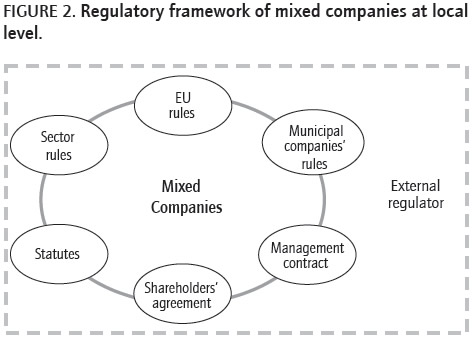

There is also the obligation of setting management contracts between the company and the municipality, where the mission, objectives, goals, price policy and relationship between the parts are drawn. Both the approval of the statutes by the municipal parliament and an economic and financial feasibility study are mandatory for the creation of these entities. Local public services, especially infrastructure services, also have dedicated legislation that needs to be taken into account. As one can see in figure 2, the mixed companies operating at the local level and providing public services are subject to a much heavier control than "regular companies".

Frequently, some of the items of the statutes, management contracts and shareholders' agreements are open for negotiation during the tender procedures (if the municipality opts for the competitive dialogue or the negotiated procedure). However, under no circumstance should these documents be handled lightly (since they are the actual regulatory contracts of mixed companies). Indeed, in iPPP arrangements the relationships between private and public partners are actually regulated by the statutes and the shareholders' agreement. These are the documents that set the rules for the company (as the allowed rate of return and the financial indicators that affect tariff reviews) and it is the shareholders' agreement that specifies the nature of the call option (Marques and Berg, 2011). The importance of the initial bid diminishes as time passes; therefore these are the documents and also the variables on which municipalities should focus their attention. Because local governments are involved in management, crucial features like price levels and price structures, investments and quality of service are periodically defined. As the lifetime of these arrangements is relatively long (not less than 10 years), and despite the initial public tender for the sale of the shares, it is easy for the private partner (usually better prepared) to justify cost overruns and the revision of the current tariffs. Hence, the incentives to be efficient and innovative are reduced, being the final users the ones who support the costs. For this reason, as we will see in the Case study, theoretical claims for added competition (during the access to the market) and efficiency (due to the framework of incentives associated with private sector entities) are usually not found in practice.

Field observations

In a recent study (Cruz, 2008) the number of local mixed companies was estimated to be around 20% of all Portuguese municipal companies. Today, there is still a lot of uncertainty about the actual number of these companies operating, but the last figures identify around 289 entities, 262 municipal and 27 intermunicipal.

Infrastructure services deserve special attention due to the large sunk investments normally involved. In practice, the competences of Portuguese local governments regarding these services include only water, urban waste and urban transport services. In Portugal, infrastructure services like electricity and telecommunications are still a responsibility of the central State. The number of mixed companies operating in the water sector in Portugal is still relatively low; however, they already represent about 1/3 of all municipal companies. Certainly this number will have tendency to increase once the municipalities begin to adapt better to this new model. Nowadays, the concession model is the preferred one regarding PPP contracts.

Mixed companies providing water, wastewater and urban waste services are subject, since 2007, to the intervention of the sector-specific regulator ERSAR (the Water and Waste Services Regulation Authority), which has the mission of performing a sunshine regulation of private water utilities (for now, the external regulator does not have jurisdiction over municipal services). The companies in the urban transport sector are also subject to the monitoring of a regulator (IMTT - Institute for the Mobility and Land Transportation). However, this external regulator was not yet endowed with the sufficient authority to effectively carry out a valuable activity.

The Portuguese water sector

In Portugal, as we have seen, there are several types of agents in the water sector (ERSAR, 2009): At the Administration level there are the public organizations in general and the regulatory authority; at the systems level there are the municipalities and their associations, municipal companies, concessions to public-public partnerships and to private firms (PPPs) and also private companies providing outsourcing services (more common in waste services).

In Portugal, there are about 302 retail water utilities (for 10.7 million inhabitants) and about 70% of the water (60% of wastewater) is provided (treated) by 18 public wholesale companies. These local services are under the exclusive responsibility of the municipalities (the local autonomy is a Constitutional principle). This clearly brings difficulties in setting up an entity that can effectively have some intervention and regulatory power over these utilities. However, with the opening of the market to private participation in 1993 it became indispensable to monitor and supervise this activity and the central State created a regulator in 1997 (nowadays known as ERSAR). Due to the restrictions already mentioned, the responsibilities of this regulator have been simply providing a non-binding opinion about the public tender documents, the contract design, and in the renegotiation processes (in both water and waste sectors). Furthermore, the primary role of the regulator is the supervision of the quality of service (sunshine regulation via yardstick competition).

Lately, there have been mainly two driving forces compelling local decision-makers to seriously consider the "PPP route". First, the recent and more demanding quality standards imposed by law and enforced by the sector specific regulator require new investments in water infrastructures. Second, the recent and increasingly strict debt limits presented to municipalities reduce their ability to invest. Besides, there are some indications that private operators might show a higher total factor productivity (or TFP, a concept dealing with all multiple inputs and all multiple outputs involved in the production process; see Marques, 2008) when compared to public water utilities.

By the beginning of 2009, the number of public tenders for PPP arrangements reached 38 in the water sector, encompassing 26% of the total Portuguese population (which was about 10.3 million at that time). Up to that date, 29 contracts were signed, five cancelled and the remaining still in negotiation. Of all signed contracts, only five corresponded to iPPPs (which means that only one more mixed company was created by the time this paper was written). Table 1 summarizes some of the most important figures related to these PPPs. To collect the data, we looked at the water service operators of all 308 Portuguese municipalities. We then checked the public call for tenders issued by all municipalities that opted for PPP arrangements in this sector. Some of the information was collected by the authors (we contacted the operators and respective local governments directly); however, most of the data is made publicly available by the sector-specific regulator.

There seems to be a healthy number of different private investors willing to engage in competition for the market. However, this is not translated in the number of actual bids; probably due to the time consuming process or to the discretion of the evaluation procedure (Marques and Berg, 2010). The fragility of the contracts signed is self-evident; despite the youth of the agreements, half of the PPP contracts (concession agreements) have already been renegotiated. This means that, most of the times, local governments enter in unbalanced settlements, most likely with an ineffective risk allocation. Bearing this in mind, the fact that, in Portugal, these water PPPs often produce better outcomes (regarding cost efficiency) than 100% public utilities is even more startling (e.g. see Correia and Marques, 2011 for the relative efficiencies of public and private utilities). Mixed companies represent a relatively new procurement model for Portuguese municipalities. Being very recent, renegotiation is not yet an issue for these specific PPP arrangements. Moreover, in theory, the relational character of mixed companies should be crafted precisely to avoid costly renegotiations. However, as we will see in the next sections, several "traps" may be embedded in the regulatory contracts of these governance structures (which often leads to a poor protection of the public interest).

A mixed company in charge of local infrastructure services

Regulation by contract has its pros and cons which have been both profoundly debated for decades in the literature. However, the same can be said about the regulation carried out by external entities (Demsetz, 1968). In this section we aim to shed some light on how good is the regulation that these iPPP contracts can actually provide. Furthermore, we want to identify the features that could use some improvements, acknowledge good practices and condemn any aspects that may distort the markets or simply damage the public interest.

The data analyzed here correspond to one iPPP arrangement providing water services. The elements asked for include all tender documents, the management contract set between the company and the respective municipality, the shareholders' agreement (signed between the municipality and the private partners) and the statutes of the company. We opted to keep the municipality anonymous.

Competition

A Portuguese municipality called for private participation in a mixed company including water, wastewater and stormwater services. The main aspects of the tender were the following:

- The PPP encompassed more than 30,000 customers and included wholesale and retail segments;

- The private firm would have 49% of the shares;

- The term of the PPP was indefinite;

- The municipality would only negotiate with the firm classified in second place if the negotiation with the winner was not successful;

- The bidders were required to make 60 M€ worth investments (mostly in wastewater infrastructure) and to reach a pre-defined level of coverage in the first 6 years of the PPP;

- The municipality asked for an up-front single payment of 18 M€;

- At that time, revenues from customers were less than costs;

- The evaluation model had problems that can result in the selection of a winning bid that is not necessarily the "best";

- Some criteria were inappropriate in that they do not differentiate among bidders or merely complicate the evaluation process (for example, the quality of a bank);

- Most of the sub-criteria were either arbitrary or noninformative;

- Some of the most important criteria had too little weight.

- Six private investors participated in the public tender.

In this particular case, a healthy number of bidders entered in the public tender. This is a good indicator because the competitive pressure should prevent that the prices detach from production costs (Bajari et al., 2006). On the other hand, the fact that there is no specific duration for the contract hinders the public interest; during the lifetime of the mixed company, the initial incentives lose their relevance and not having a periodical market consultation accentuates the lack of "competition for the market" (Demsetz, 1968). Some criteria (like the quality of a bank) should have been set as threshold criteria (or rejection criteria) rather than evaluation criteria. By imposing minimum standards in some crucial aspects, the public authority reduces the discretion of the multicriteria evaluation model (each criterion should be independent and the performance of the bids should be measured in a clear and objective way).

The potential to get a higher up-front payment can lead the local government to be overly optimistic regarding the initial assumptions (e.g. the actual state of conservation of the current water system) and estimates (e.g. the increase in demand). To avert this, a public sector comparator (PSC) should have been calculated ex-ante; the PSC consists in the estimation of the costs of using both traditional procurement and PPP schemes (to get a sense of the value for money that a PPP can actual provide). Nevertheless, the value for money assessment does not guarantee the affordability of the project; thus an affordability cap should also have been determined.

Risk allocation

The concept of risk is associated with uncertainty. Commonly, it corresponds to the potential for events that have uncertain consequences and may constitute threats to success. The significance of each risk depends on the project but it can be defined as the combination of the probability of an event and its consequences (Marques and Berg, 2011). There are three main phases in risk management: Risk identification, risk allocation, and risk mitigation. For public infrastructure projects, this assessment should be seen as a whole life-cycle process, starting right in the preparation and design stages and encompassing the construction, operation, and maintenance stages.

The problems related to the transfer of risk are widely discussed in the literature. The main conclusion is that, usually, in PPPs the public sector bears most of the risks (Vining et al., 2005; Broadbent et al., 2008, and Acerete et al., 2009); the more risk adverse partners (the private sector entities) manage to avoid the most important risks and hence, in order to carry out the projects, the public sector has to take responsibility for the majority of the financial risks. With mixed companies this seems to be even worse. In fact, the risks are transferred to the users. The shareholders' agreement identifies multiple situations that constitute causes for restoring the financial and economic equilibrium of the studied mixed company. It establishes conditions where any change in the proposed financial indicators is recovered in the next tariff review (every year). So the internal rate of return of the private partner is always secured. It is evident that the public interest is completely disregarded in this arrangement.

Governance

When compared with other types of PPP arrangements, the contract management of an iPPP has some additional difficulties. In this case, the public authority (who is in charge of contract management) has few incentives to apply sanctions against itself (as it is effectively involved in the services management). Hence, it tends to agree with proposals to raise tariffs very easily. The existence of an external regulator with effective power over these entities could help to avoid these practices. We acknowledge that contract monitoring entails significant costs; however, without a good framework of incentives (and penalties) there is little chance of achieving a successful long-term agreement.

The fact that the company has to see its annual account, performance, and activity reports approved in the municipal parliament is positive. However, the definition of performance indicators to manage the contract was not carried out. There should have been criteria that allowed for the application of awards and sanctions related to the private partner's performance, preferably connected with the payment mechanisms. Furthermore, with the exception of the bid evaluation, local governments do not usually resort to the consultancy of experts in other phases of the PPP process; the substantial difference in the resources available for the public and private parties is another factor contributing to the unbalance of the settlements.

To ensure the success of an iPPP arrangement, a good level of communication between local governments, private partners, and the users must be secured at all times. The relationship between these three parties is fundamental for the success of the model. Focusing just on the ex-ante phase of the PPP is not enough. In this case, the local government did not foster any kind of stakeholder participation.

Policy implications

Drawing up on the extensive literature review and on the case study analysis undertaken, it is now possible to suggest some policy measures on the following dimensions:

Risk and accountability

Local councilors must provide strong evidence that the PPP arrangement is the best option. The fact that it may be the only option is not enough in order to protect public interest. In the feasibility and viability studies, the municipality must identify, classify and decide how the risks of the project should be allocated (this information should be clear in the bidding documents). The management contracts binding municipalities and municipal companies must be quickly firmed; in order to enable effective accountability systems, these documents should clearly (and in a simple manner) define the evaluation parameters and quantitative goals. A negative evaluation of the firm's performance (taking into account the realistic goals that have been set in the management contracts) ought to have visible consequences.

Opportunism

To fight opportunism, municipalities should be obliged to really invest in the public tender procedure. Taking into account the long-term character of the contracts, these are once in a lifetime procedures. The public bidding documents must contain all the relevant information and nothing more than that. These documents must lead to comparable bids, not leaving room for any creative accounting of some variables (and to phenomena like the winner's curse). Most of the traditional criteria should be set as standards for bidder qualification. The shareholders' agreements as well as the statutes of the companies are of crucial importance, as these are the documents that will actually regulate their performance. A draft of these documents must be provided in the bidding documents with the most important items not open for competition. For the resolution of future disputes, depending on the global value of the contracts, some structures (like dispute boards among others) should be considered in order to avoid legal litigation.

Transparency

As it is well-known, transparency is a principle highly encouraged within the EU. In addition, PPPs are complex and should therefore be subject to public scrutiny. This is especially crucial in the mixed company model. The publication of all the participations carried out by municipalities in other entities (and also the participations by those entities in other organizations) should be mandatory. All public capital must be easily traceable. For instance, consider the excellent example of Transport for London (the regulator of urban public transport services in London) which publicly presents on its website all the bids and explains its final choices in a tender-by-tender basis (Amaral et al., 2009). This governance model has potential to improve the principle- agent relationships and increases the transparency within the companies and between the public and private sectors by reducing information asymmetries.

Regulation

There is a belief that an external regulator is only mandatory when there is private capital involved. The authors profoundly disagree with this idea. The several evidences in the literature pointing out the cost inefficiency of public entities when compared with private ones are the proof we need (e.g. Correia and Marques, 2011). Furthermore, it seems to be an overlap to invest in regulatory contracts and in external regulation at the same time; however, the practice shows that this may be a "necessary evil". While private investors remain to be better prepared to enter in a PPP negotiation than the public partners, the regulation by contract will always be ineffective. The external regulator must constitute an important ally for the municipalities in these negotiations and, while non-binding due to the local autonomy principle, its opinions should be carefully taken into account by local councilors. Whenever it is feasible, economic regulation should be considered.

This paper intends to cope with the dispersion found in the literature framing the choice of the mixed company model to produce local public services. Most of the investigation carried out in this field of research is at a macro level, being either descriptive, trying to explain what happened with national public capital companies, or conceptual, defining theoretical capabilities and disabilities of the model based on observation. The choice of local governments should embrace the model which allows for welfare maximization. In theory, the mixed company model seems to be able to deliver this purpose; however, it utterly depends on the quality of contract design. Moreover, local decision-makers have to take responsibility for their choices; otherwise local governance stops to be a learning process. In principle, mixed companies provide a way for municipalities to actively participate in the market. These governance structures appear precisely so that local governments can keep control over the services while coping with fiscal constraints. However, iPPP arrangements should be only used in infrastructure projects framed by singular uncertainty and asset specificity. Indeed, crafting an incomplete relational contract is not easy and it should not be the preferred choice when market failures are not so severe (e.g. when investments are not "sunk"). In these cases, the use of mixed companies will hardly be optimal.

Recent research has been arguing that the times in which simple privatization was the straightforward answer to overcome all public sector hurdles are over (Ramesh and Araral, 2010). In fact, practitioners are beginning to be aware of the problems of contracting out. The mixed company model could be a way of merging two worlds that have been perceived as evolving in separate (Clifton et al., 2007). Nevertheless, empirically, we have seen that the mixed company model will hardly be superior to any other governance structure if several special concerns are not taken into account. In line with the evidence gathered by Bel et al. (2010), we think that, more important than focusing on the make or buy dilemma (or on a combination of these two dimensions -the case of mixed companies), one should emphasize the transaction costs involved and the characteristics of the policy environment for each type of infrastructure service.

As in all PPP arrangements, the negotiation with the private partners involved in the partial privatization processes can be impaired by the current adverse economic conditions. The economic crisis can lead to ex-ante opportunism by the private bidders who know that the state needs to cut on public debt and carry out privatizations. Ideally, these public authorities should wait for a more favorable economic environment. However, waiting may not be an option anymore.

Further research on mixed public-private provision of local public services should concentrate on assessing the performance of the model. For example, within a specific sector (as water supply, urban waste services, etc.) the mixed company model should be compared with all the remaining governance structures. Consequently, it would be possible to assess how far away this particular model is from the efficient frontier. Besides the comparison with the best practices, also an evaluation regarding the effectiveness and the quality of service related to this model should be developed. The identity of the shareholders is not irrelevant; hence all economic analysis should take this into consideration. The interests and aptitudes of different shareholders diverge immensely in mixed public-private companies and these facts have implications for the companies' performance.

The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their comments that helped to improve the manuscript.

Acerete, B., Shaul, J. & Stafford, A. (2009). Taking its toll: The private financing of roads in Spain. Public Money & Management, 29(1), 19-26. [ Links ]

Amaral, M., Saussier, S. & Yvrande-Billon, A. (2009). Auction procedures and competition in public services: The case of urban public transport in France and London. Utilities Policy, 17(2), 166-175. [ Links ]

Bajari, P., Houghton, S. & Tadelis, S. (2006). Bidding for incomplete contracts: An empirical analysis. NBER Working Paper, no. 12051. [ Links ]

Bel, G. & Fageda, X. (2010). Partial privatization in local services delivery: An empirical analysis on the choice of mixed firms. Local Government Studies, 36(1), 129-149. [ Links ]

Bel, G., Fageda, X. & Warner, M. (2010). Is private production of public services cheaper than public production? A meta-regression analysis of solid waste and water services. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 29(3), 553-577. [ Links ]

Bilodeau, N., Laurin, C. & Vining, A. (2007). "Choice of organizational form makes a real difference": The impact of corporatization on government agencies in Canada. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 17(1), 119-147. [ Links ]

Boardman, A., Eckel, C. & Vining, A. (1986). The advantages and disadvantages of mixed enterprises. In Multinational corporations and state-owned enterprises: A new challenge in international business (pp. 221-224). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. [ Links ]

Bognetti, G. & Robotti, L. (2007). The provision of local public services through mixed enterprises: The Italian case. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 78(3), 415-437. [ Links ]

Boyne, G. (2003). Sources of public service improvement: A critical review and research agenda. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 13(3), 367-94. [ Links ]

Broadbent, J., Gill, J. & Laughlin, R. (2008). Identifying and controlling risk: The problem of uncertainty in the private finance initiative in the UK's National Health Service. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 19(1), 40-78. [ Links ]

Cambini, C. (2010). Regulatory independence and political interference: Evidence from EU mixed ownership utilities. FEEM Working paper no. 69, Milan. [ Links ]

Chiu, Y. (2003). Estimating the cost efficiency of mixed enterprises in Taiwan. International Journal of Management, 20(1), 81-87. [ Links ]

Chiu, Y., Hu, J. & Li, Y. (2002). Cost inefficiency of Taiwan's mixed enterprises. In Productivity and economic performance in the Asia-Pacific Region (pp. 208-227). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [ Links ]

Clifton, J., Comín, F. & Díaz-Fuentes, D. (2007). Transforming Public Enterprise in Europe and North America. New York: Palgrave. [ Links ]

Correia, T. & Marques, R. (2011). Performance of Portuguese water utilities: How do ownership, size, diversification and vertical integration relate to efficiency? Water Policy, 13(33), 343-361. [ Links ]

Cruz, N. (2008) A viabilidade das empresas municipais na prestação de serviços de infra-estruturas urbanas. MSc. Thesis, Technical University of Lisbon. [ Links ]

Cruz, N. & Marques, R. (2011). Viability of the Portuguese municipal companies in the provision of infrastructure services. Local Government Studies, 37(1), 93-110. [ Links ]

Demsetz, H. (1968). Why regulate utilities? Journal of Law and Economics, 11(1), 55-65. [ Links ]

Devas, N. & Delay, S. (2006). Local democracy and the challenges of decentralising the State: An international perspective. Local Government Studies, 32(5), 677-695. [ Links ]

Eckel, C. & Vining, A. (1982). Toward a positive theory of joint enterprise. In Managing Public Enterprise (pp. 209-222). New York: Praeger. [ Links ]

Edelenbos, J. & Teisman, G. (2008). Public-private partnership: On the edge of project and process management. Insights from Dutch practice: The Sijtwende spatial development project. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 26(3), 614-626. [ Links ]

ERSAR (2009). Annual Report on Water and Waste Services in Portugal. Lisbon: The Water and Waste Services Regulation Authority. [ Links ]

Essig, M. & Batran, A. (2005). Public-private partnership: Development of long-term relationships in public procurement in Germany. Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management, 11(5-6), 221-231. [ Links ]

Greve, C., Flinders, M. & Thiel, S. (1999). Quangos-What's in a name? Defining Quangos from a comparative perspective. Governance: An International Journal of Policy and Administration, 12(2), 124-146. [ Links ]

Hart, O., Shleifer, A. & Vishny, R. (1997). The proper scope of government: Theory and an application to prisons. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), 1127-1161. [ Links ]

Hodge, G. & Greve, C. (2010). Public-private partnerships: Governance scheme or language game? Australian Journal of Public Administration, 69(s1), S8-S22. [ Links ]

Hood, C. (1991). A public management for all seasons? Public Administration, 69(1), 3-19. [ Links ]

Klein, M., So, J. & Shin, B. (1996). Transaction costs in private infrastructure- are they too high? Washington, DC: World Bank Publications, Note no. 95. [ Links ]

Lobina, E. & Hall, D. (2007). Experience with private sector participation in Grenoble, France, and lessons on strengthening public water operations. Utilities Policy, 15(2), 93-109. [ Links ]

Marin, P. (2009). Public-private partnerships for urban water utilities: A review of experiences in developing countries. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications. [ Links ]

Marques, R. (2008). Comparing private and public performance of Portuguese water services. Water Policy, 10(1), 25-42. [ Links ]

Marques, R. & Berg, S. (2010). Revisiting the strengths and limitations of regulatory contracts in infrastructure industries. Journal of Infrastructure Systems, 16(4), 334-342. [ Links ]

Marques, R. & Berg, S. (2011). Public-private partnership contracts: A tale of two cities. Public Administration, 89(4), 1585-1603. [ Links ]

Marra, A. (2007). Internal regulation by mixed enterprises: The case of the Italian water sector. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 78(2), 245-275. [ Links ]

Maw, J. (2002). Partial privatization in transition economies. Economic Systems, 26(3), 231-247. [ Links ]

McQuaid, R. & Scherrer, W. (2010). Changing reasons for public-private partnerships (PPPs). Public Money & Management, 30(1), 27-34. [ Links ]

Mok, H. & Chau, S. (2003). Corporate performance of mixed enterprises. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 30(3-4), 513-537. [ Links ]

Moore, A., Nolan, J. & Segal, G. (2005). Putting out the trash: Measuring municipal service efficiency in U.S. cities. Urban Affairs Review, 41(2), 237-259. [ Links ]

OECD (2009). Government at a Glance 2009. Paris: OECD Publishing. [ Links ]

Oelmann, M., Böschen, I., Kschonz, C. & Müller, G. (2009). Ten Years of Water Services Partnership in Berlin. Bad Honnef: WIK Consult. [ Links ]

Osborne, D. & Gaebler, T. (1993). Reinventing government: How the entrepreneurial spirit is transforming government. New York: Plume. [ Links ]

Pollitt, C., Talbot, C., Caulfield, J. & Smullen, A. (2005). Agencies: How governments do things through semi-autonomous organizations. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Quiggin, J. (2002). Contracting out: Promise and performance. Economic and Labour Relations Review, 13(1), 88-104. [ Links ]

Raffiee, K., Narayanan, R., Harris, T. & Collins, J. (1992). Cost analysis of water utilities: A goodness-of-fit approach. Atlantic Economic Journal, 21(3), 21-29. [ Links ]

Ramesh, E. & Araral, E. (2010). Introduction: Reasserting the role of the state in public services. In Reasserting the public in public services: New public management reforms (pp. 1-16). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ridley, F. (1996). The new public management in Europe: Comparative perspectives. Public Policy and Administration, 11(1), 16-29. [ Links ]

Sathye, M. (2005). Privatization, performance and efficiency: A study of Indian banks. Vikalpa, 30(1), 7-16. [ Links ]

Schaeffer, P. & Loveridge, S. (2002). Toward an understanding of types of public-private cooperation. Public Performance & Management Review, 26(2), 169-189. [ Links ]

Schmitz, P. (2000). Partial privatisation and incomplete contracts: The proper scope of government reconsidered. Finanzarchiv, 56(4), 394-411. [ Links ]

Shleifer, A. (1998). State versus private ownership. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12(4), 133-150. [ Links ]

Sueyoshi, T. (1998). Privatization of Nippon Telegraph and Telephone: Was it a good policy decision? European Journal of Operational Research, 107(1), 45-61. [ Links ]

Tauchmann, H., Clausen, H. & Oelmann, M. (2009). Do organizational forms matter? Innovation and liberalization in the German wastewater sector. Journal of Policy Modeling, 31(6), 863-876. [ Links ]

Verdier, A., Martinez, S. & Hoorens, D. (2004). Local public companies in the 25 countries of the European Union. Paris: Dexia Editions. [ Links ]

Vining, A., Boardman, A. & Poschmann, F. (2005). Public-private partnerships in the US and Canada: There are no free lunches. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 7(3), 199-220. [ Links ]

Vining, A. & Boardman, A. (2006). Public-Private Partnerships in Canada: Theory and Evidence. UBC P3 Project Working Paper, no. 04. [ Links ]

Vining, A. & Weimer, D. (2006). Economic perspective on public organizations. In Oxford handbook of public management. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Warner, M. & Bel, G. (2008). Competition or monopoly? Comparing privatization of local public services in the US and Spain. Public Administration, 86(3), 723-735. [ Links ]

Williamson, O. E. (1985). The economic institutions of capitalism: Firms, markets and relational contracting. New York: The Free Press. [ Links ]