Introduction

Modern society -especially in the West- has been functioning in a capitalist-based economy where money is usually seen as the ultimate goal of a worker's life, making people prone to completely separate two moments of their routine: when working (making money) and when not working (making life). Competitiveness is also a remarkable characteristic of capitalism that encourages the search and acquisition of a variety of items by the best price while ensuring that the most prepared competitors (companies, brands, sports[WO]men, etc.) win.

As argued by Debord (2003), capitalism is an integrated spectacle in which it is extremely difficult to disentangle our personal lives from our working lives. This is even harder now, because of the technological advancements. Therefore, our bodies become machines of production and consumption, in a cycle where we work to consume and consume to exist. As the author emphasizes "[t]he spectacle's form and content are identically the total justification of the existing system's conditions and goals. The spectacle is also the permanent presence of this justification, since it occupies the main part of the time lived outside of modern production" (p. 15).

This rapid growth in capitalist global market economy has arisen concerns regarding social and environmental issues, including environmental stewardship and justice in economic life (Shearer, 2002). Disparities among individuals in terms of income generation and wealth accumulation are highly evident, especially when we compare the richest with the poorest, or top earners with bottom earners. A recent report by the World Inequality Lab (2018) exposes an alarming reality: in 2016, those in the top 1% of global income earners received 22% of total income, while the bottom 50% received only 10%. Pandemic has worsened inequality even more.

A shadow is cast over those who don't reach high grounds. In a capitalist economy, winners build up advantages while losers build up disadvantages on future competitions, making it constantly harder to achieve a notorious position on the economic hierarchy (Singer, 2002). Vanegas et al. (2020), for instance, in a study carried out in López de Mesa neighborhood (Medellín, Colombia), indicated that women with access to university education and with house savings have better control over their finances than their counterparts, which, in turn, widens even more the gap between rich and poor, forming a distorted ever-growing cycle.

This predatory competition in a globalized market capitalism, on the one hand, as Shearer (2002) presents, has produced considerable benefits, such as cheaper consumer goods, an increase in standard of living, and higher per capita income for many. On the other hand, to secure these competitiveness, government and individuals might give up wage and benefits provisions, job security, maximum workweek provisions, or the right for collective representation by unions. Thus, the logic underneath capitalism and the neoliberal economy is that the economic agent, whether an individual or a corporation, is only accountable for the achievement of their own private economic goals, and that the collective good is in agreement with the pursuit and attainment of private interest. It is also congruent to the libertarian argument, which states that we should be free to act anyway we want as long as no harm is done to others. These conceptions lead to the logic that the individual is responsible for their own destiny, which, at the same time that empowers them, also diminishes the importance of a community engaged in improving their members' lives.

Ribeiro and Ribeiro (2012) prove that people with physical disabilities face initial difficulties at work, but that they are motivated by their recognition and the possibility of developing their identities as workers, as well as by the need to overcome challenges and to manage conflicts. The importance of career development programs is also emphasized. These authors conclude that career development programs are key on building opportunities for those with disabilities, stimulating a more receptive workplace that is based on differences and on the possibility of constructing an identity at work, even if the process is still marked by several conflicts, meaning that they will have to face the difficulties of being inserted.

If it is already difficult for those with physical disabilities, the prospect is much more critical for individuals with mental illnesses. Few are the companies apt to hire, train and maintain a worker with this health condition, and fewer those willing to. The fear of a mental breakdown due to conflicts, deadlines and company's goals, among any other routine scenarios presented in any enterprise, discourages employers to hire individuals with mental illnesses, who are usually seen as, simply, a "crazy/lunatic/disturbed person." As Ribeiro (2009) poses:

The antagonism and the impossibility of synthesis of the work/craziness duality relegated the person labelled as "crazy" to the exclusion of any construction in the labor world, reducing his/her existence to the stigma of crazy, and therefore, destined to live apart of the action of developing social relations and to occupying a position of socially assisted, since s/he would be the holder of a deteriorated identity. (p. 99)1

In this paper, when referring to "mental illness" or "mental health issues," we are focusing on more severe forms of mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, multipolarity or autism. However, we recognize there is a wide variety of other forms of mental disorders suffered by an increasing proportion of the population, some of which are intrinsically correlated to work conditions.

The (re)integration and emancipation of a mentally ill individual in society must include labor and its externalities, such as income generation and personal empowerment. Here, empowerment is understood as "a social-action process that promotes participation of people, organizations, and communities towards the goals of increased individual and community control, political efficacy, improved quality of community life, and social justice" (Wallerstein, 1992, p. 198).

It is imperative to open our minds to new forms of economic relationships advancing in the real world and through academic research towards a more critical vision, thinking of and building a society that won't let itself be steered in the name of self-interestedness and individuality. Calás et al. (2009) point of view is that the traditional perspective on entrepreneurship is aimed at reproducing the current economic system (i.e. market capitalism), based on the assumption that the collective good shall be achieved by the pursuit of economic self-interest. This perspective fails to consider entrepreneurship as a much more complex phenomenon, and that the simple fact that one is engaging in entrepreneurship means also engaging in a process of social change.

Therefore, we aim to address this issue at hand from the perspective that individuals of a society who become excluded by the dominant economic model are able to emancipate themselves from the institutional violence of the logic of capitalist market and economy by being creative and building emancipatory venture models, offering alternative means of work and income generation, gaining control and accountability over their own (personal, financial, accounting and operational) decisions, respecting individual working rhythm and their limitations (both in personal and social lives), including rather than excluding, being collective and not individualistic, being supportive instead of indifferent, teaching, building bridges of communication, destroying barriers, bringing people closer rather than fending them away, and, finally, showing that traits that are considered a weakness in the capitalist model of production can be developed as potentialities in the solidarity economy (SE). Therefore, we shall recognize all these as health promotion actions.

On the other hand, opposing the capitalist logic, SE has as its principle the unity between cooperative labor and collective ownership of the means of production. SE also aims to prioritize solidarity over competition, the preservation of employment over profitability, and the distribution of the outcomes of work among direct producers (Pitaguari, 2010).

The approach of this study falls in the realm of SE as an alternative for traditional (and often excluded) entrepreneurship, and our main fields of study are two Brazilian Solidarity Economy Ventures (SEVS), O Bar Bibitantã and Ponto Benedito de Economia Solidária e Cultura, that work for the social and financial inclusion of mentally ill individuals.

Our study is positioned in the strand of the critical accounting research proposed by Bay et al. (2014), arguing for financial literacy as an emancipatory and transformative practice. As reinforced by Stieger and Jekel (2019), traditional concepts of financial literacy can function as a legitimizing mechanism for the (re)production of neoliberalism and neoclassical economy's ideals. For their part, Lefrançois et al. (2017) show that a financial education course can produce financial savvy citizens instead of educating critically good citizens.

After this introduction, we explore the theoretical literature discussing topics such as health promotion, solidarity economy, and financial education, weaving relationships among them and critical accounting and exposing the interdisciplinarity of this study. Next, we present the methods used, based on an action-research framework. Subsequently, we learn more about O Bar Bibitantã and Ponto Benedito, and analyze how the implementation of a financial education program for the worker-members of these enterprises took place, highlighting once more the fundamental importance of the critical accounting perspective. We conclude with an in-depth reflection on the lessons we can draw from the experience and how it can positively influence future practices and inspire further research on the field, following the path opened by Bay et al. (2014).

Theoretical framework

Many authors have showed how SE is an efficient way of promoting better work conditions, encouraging workers to behave honestly, proudly and cooperatively (Fonteneau et al., 2011; Gaiger & Corrêa, 2011; Ministério da Saúde do Brasil, 2005; Neamtan, 2002; Singer, 2002), which is achieved mainly due to its self-management aspect and the focus on social outcomes rather than financial profit. Other authors studied how SE relates to the treatment and social inclusion of individuals with mental illnesses (Aranha e Silva, 2012; Aranha e Silva & Fonseca, 2002; Ballan, 2010; Lussi & Pereira, 2011; Matias, 2006; Nicácio et al., 2005). Their finding is an incredible and tangible advance on the self-acceptance of those people, enabling them to regain their citizenship, allowing them to see themselves as part of a larger group.

Historically, in Brazil, and in most of the world, those diagnosed with mental illnesses and chemical dependency have been excluded from society, stigmatized, and considered lost causes, as a burden to society, due to a belief that they could not be economically productive (Ribeiro, 2009), that the kind of work they are capable of doing has lower social and intellectual value (Goodwin & Kennedy, 2005), and by an overall ignorance regarding what kind of work mentally ill employees are capable of doing and which modifications in the workplace are needed to maintain them (Wu et al., 2009). These individuals were (and still are) perceived as liabilities rather than understood as assets for our society. This is the only story attributed to them. But it is not their only story, neither is their best story (Adichie, 2009).

The Brazilian psychiatric reform, a movement born around the late 1970s, points out the inconveniences of the asylum-centered model for the treatment of individuals with mental illnesses, the only possibility at that time. The reform was led by mental health professionals and researchers who fought for developing a new and more humane manner of how society sees and deals with people with mental health issues in the country. Rather than improving the patient's life while striving to cure the disease, asylums hide and exclude patients from society, in an expensive and lifelong hospitalization process (Gonçalves & Sena, 2001). In 1987, the Movement of Mental Health Workers proposed the motto "for a society without asylums," solidifying the anti-asylum and pro-deinstitutionalization movements and proposing the transformation of how mental illnesses are dealt with. The psychiatric reform, therefore, came to allow the reintegration of mental health service users in society and a relevant change in mental health treatment logic, transitioning from psychiatric hospitalization to community care. It was a lengthy process accomplished by the training of medical doctors, nurses and psychologists, the reduction of beds in psychiatric hospitals, and the creation and expansions of a considerable number of Centers for Psychosocial Care (Centro de Atenção Psicossocial, CAPS) (Matias, 2006; WHO, 2007).

Studies concerning mental health care under the perspective of deinstitutionalization and psychiatric treatment indicate the importance of labor in the form of therapy, as well as of therapy in the form of labor. Many attributes found in labor, such as productivity, value production, business' subjectivity, rights, duties, and work-worker relations, produce relevant challenges to be thought of, faced, questioned and surpassed. In short, they constitute an important source of learning on the worker's life, highlighted when this worker is placed upon the margins of society, as occurs with people with a mental illness (Lussi & Pereira, 2011; Nicácio et al., 2005).

Aranha e Silva and Fonseca (2002) studied the daily routine of CAPS users in São Paulo, relating their comprehension about working on a local project and identifying the difficulties imposed by the hegemonic capitalist modes of production, that is, competition, prejudice against marginalized groups, and insensibility towards the limits and difficulties of others. The authors considered the work in this project as a valid alternative and opportunity for those with mental illness to be included in a productive activity, and as a way to access a social place that makes them regain their citizenship. Traditional psychiatry and common sense recognize labor as a form of mental treatment and as a therapy -a mediating apparatus which detaches the suffering of the human who is its bearer-, dissociating the morbid experience of the illness from the possibility of understanding the self, so that labor acquires a meaning that is articulated with the contemporary world, time, and concepts of the social classes in which we live, relating such meaning to a right to citizenship that any person pursues as a source of emancipation and autonomy (Freire, 2003; Rindova et al., 2009).

People with a mental illness, in general, are seen as not able to endure the pressure required by the standard capitalist model of work. We wonder if it is good for someone to be able to endure it. To overcome such difficulties, the implementation of business models based on SE as a treatment for these people was studied, considered and encouraged (Ministério da Saúde do Brasil, 2005). The concept of SE2 has been receiving more attention since 1995 as a solution to a growing desire by social movements to propose an alternative model of economic development contrary to the neoliberal model, and as an alternative for the inclusion of excluded segments of society in the realm of work and productivity, enabling these groups to produce their own subjectivities through access to a place in the world of work (Neamtan, 2002). Through the constitution of solidarity enterprises, a diverse way of organizing work would conceive the inclusion of people set in the margins, distant from the framing of traditional workers, whose pace and capabilities could then be valued, thus allowing them to regain their right to produce and be part of society.

It is worth noting that there are already many studies in the fields of mental health (Lalonde, 1974; Lussi & Pereira, 2011; Ministério da Saúde do Brasil, 2005; Ribeiro, 2009; Ribeiro & Ribeiro, 2012; WHO, 2009), financial education (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2014; Meier & Sprenger, 2013; Reifner & Schelhowe, 2010), and SE (Gaiger & Corrêa, 2011; Neamtam, 2002; Lima, 2013; Singer, 2002), and in the intersections between mental health and financial education (Harper et al., 2015, 2018), financial education and SE (Núcleo de Economia Solidária da USP, 2013; Yunus, 2007), and SE and mental health (Aranha e Silva, 2012; Aranha e Silva & Fonseca, 2002; Ballan, 2010). However, there is a lack of studies addressing the three fields at the same time. We intend, with this article, to conjoin the topics of mental health, financial education and SE, building on the knowledge of emancipatory practices for people with mental illnesses.

Solidarity economy

For Singer (2002), Neamtan (2002), Ballan (2010), and Lussi and Pereira (2011), SE is an alternative to capitalism.

While the latter focuses on capital, the former focuses on individuals, seeking to tackle dynamics that cause inequalities and marginalization. SE suggests that in order for a society to have equity (or equality) among its members, its economy must be based on solidarity instead of competitiveness. SE proposes that through cooperation and harmony between different activities and/or entities and the sharing of knowledge and decisions, we can transcend self-interest and individuality so challenges can be overcome, and equality can be attained (Gaiger & Corrêa, 2011). This is the reason why solidarity economy ventures (SEV), in this point similarly to cooperatives, operate using the logic of self-management and having all its members as owners and as decision-making agents, independently of their role. Some important characteristics of SE processes are the interest in shedding light on innovation, encouraging community participation, and supporting the creation of small initiatives aimed at responding to particular social problems. The network established by SEV is mainly local and makes use of reciprocity mechanisms relying on hybrid-resources such as monetary and non-monetary transactions, market-based and non-market-based relations, paid jobs, and volunteering.

The key to efficiently create and maintain a SEV is the perception of each individual as unique and, at the same time, as valuable as any other. It contrasts with the hierarchy commonly observed in most organizations. To maintain this principle, all worker-members within a solidarity venture share the same amount of the company's capital and are entitled to exactly one vote in all decisions. There is no boss in a solidarity venture. A SEV is sustained by self-management, and all decisions, big or small, specialized or general, strategic or operational, are taken in general assemblies. The division of tasks or jobs is done according to personal preferences and abilities relative to the needs of the company. There are positions that can be seen as of higher or lower hierarchy, such as delegates or directors, but the assembly, through a democratic voting system, has full control over these positions, who in turn have responsibilities over the worker-members. In SEV, orders flow bottom-up, whereas information flows top-down.

In the capitalist system, workers earn unequal wages, according to a scale that roughly reproduces the value of each type of work determined by its supply and demand on the labor market. This dynamic creates social inequality, since a disqualified person will seldom have the opportunity to study or acquire new experiences and, consequently, to ascend the ladder in the labor market. In SEV, there are no salaries, but rather withdrawals that vary according to revenue obtained. In the assemblies, associates vote collectively how the withdrawals should be allocated: if equally among all or using some criterion of distribution. SE, for Singer (2002), through self-management, can be:

[...] a better alternative to capitalism. Better not in strict economic terms, [... ] better because it enables people to adopt a better life as producers, savers, consumers, etc. Better life not only in the sense that individuals can consume more with less productive effort, but also better in terms of relationships with their families, friends, neighbours, co-workers, classmates, etc.; each has the freedom to choose the work s/he derives more satisfaction from; each has the right to be autonomous in productive activity and not to submit to the command of others, and can fully participate in decisions that affect his/her life; and has certainly that the community will never abandon him/her. (p. 114)

Lima (2013) deepens the issue of how SE promotes a more egalitarian and healthier environment for workers, their families, and the entire community. Her publication is the result of a series of interviews with workers of a recycling SEV, most of them with humble and poor backgrounds. The solidarity work has allowed all of them to strengthen their social and family ties, to feel cared for within the venture, to have autonomy, and to dream of a more ambitious future. The concept of coopetition is also addressed: the cooperative competition, where the presence and the labor of others are not seen as a threat but as an opportunity through which everyone can learn and grow.

A special case in the context of SE are the mental health ventures, which have been understood as an opportunity to the social and economic re-inclusion of those with mental health illnesses and, thus, as vehicles for health promotion.

Health promotion

Czeresnia (1999) and Terris (1990) point out that the idea of health promotion goes beyond the medical approach of diseases and diagnoses. It is about the strengthening of both individual and collective capacities through active participation in building, organizing and accounting for the multiplicity of factors that determines health conditions, thus developing healthful living standards.

Financial income has also been stated as a fundamental issue to which actions towards a healthier population should be addressed. The inequalities in wealth and income can be perceived in the World Inequality Lab's report (2018). For his part, Wilkinson (1992) studied the relationship between income and life expectancy. The author concludes in his study that -considering the 23 developed countries that were part of the OECD between 1970 and 1986- there was a sufficiently strong association in cross sectional data between income distribution and life expectancy. Kaplan et al. (1996), in their study comparing health effects and income inequalities between and within states in the United States, showed that there was a consistency in associating higher income inequality levels with poorer health effects (although they could not prove this claim). Therefore, these authors concluded that a more egalitarian income distribution has positive impacts on health outcomes.

Considering all the above, the importance given by the World Health Organization (WHO) to income as a principle of health promotion seems to be reasonable. The chances of people with low economic power to properly invest in education, health, housing and food are very low. Therefore, these people are more likely to have poorer health outcomes throughout life and possibly negative impacts in other areas of their lives, which generates direct and indirect effects on their process of empowerment towards a participation in community life and in the control of their destinies. In addition to attaining a decent income, for health promotion, it is also necessary to have the ability to deal with money, issue that has been called financial literacy.

Financial education (or literacy)

Bay et al. (2014) state that financial literacy "cannot merely be viewed as the ability to read and write in the language of finance and accounting" (p. 36). Consequently, financial literacy shall not be understood as a set of universal topics and contents that someone needs to be proficient at, independently of the historical, social or political context. Instead, for these authors, financial literacy "is a concept that needs to be situated and studied in practice because the characteristics that constitute financial literacy, or those that apply to it, vary with time and place" (p. 36). The authors then propose a social turn "from a focus on the inherent to the affected, from skills to practices, from cognitive dispositions to cultural conditions" (p. 38). Consequently, they are proposing the understanding of a situational and contextual financial literacy, which concerns not what we know but what we do with our literacy, leading to a literacy practice. They call it a situated model of financial literacy, and explain that:

The situated model of financial literacy [...] is not characterised by developing numerical skills or by teaching financial vocabulary (in its narrow sense). Rather, this financial literacy endeavour asks the participants to reflect on their role in society and to consider the necessity of a practice in which financial competence is a given. (p. 41)

Stieger and Jekel (2019) point out that the financial literacy concept discussed in economics education is also unclear. They criticize that most studies assess financial literacy by testing the subject's financial factual knowledge and numerical skills in an attempt to predict how the individual will behave in certain financial situations based on the number of correct answers, and not considering other conceptual views that are non-cognitive and that focus on other aspects like motivation and attitudes. Interventions in financial literacy, therefore, should consider soft skills like willingness and confidence to take risk and propensity to planning. The authors of this study criticize and conclude that current studies and financial or economics education programs are conceived as to attend a neoliberal political project in order to justify, legitimize, and perpetuate the current dominant political and economic ideology of dominant groups, putting in check the possibilities of transformative and emancipatory ideas by individuals.

Lefrançois et al. (2017) build on the same position by discussing the implementation of a financial education course in Québec's high school education program. This course, the authors argue, focuses on producing 'good,' financially savvy citizens in an effort to avoid or weaken economic crises, instead of 'critical,' socially-versed citizens, able to perceive and deal with the controversies of modern capitalism.

Individuals who are not prepared or instructed to make decisions in social interactions can have their social and financial well-being put at risk. People with mental health issues often are in this situation due mainly to their poor psychosocial condition caused by the lack of a proper formal educational level, since people with mental illnesses are more frequently excluded from educational institutions early in life. Another aggravating factor is the weak supportive networks that many of them have access to. It is common for the mentally ill to be marginalized by their own family and local community due to a general prejudice or stigma. On the other hand, as they face many struggles in life and must adapt to survive, many of them develop skills and knowledge through experience rather than formal education, and may find alternative supportive networks from people who better understand their issues and needs. But we, authors of this paper, sitting comfortably on our throne of academic superiority, supposed at first that this informal knowledge was weak, naive and limited to subsistence. Spoiler alert: We were wrong!

Harper et al. (2015) deepen the discussion by arguing that people with mental illnesses are even more distant from obtaining a decent financial knowledge, since they struggle to meet the most basic needs, such as food and rental money. The causes and consequences of those conditions are (i) high rates of unemployment among this group of people, (ii) the deepening of social stigmas and prejudice towards them, and (iii) social exclusion, a factor which worsens those aspects. Additionally, more than half of the people with mental illness(es) do not receive adequate treatment, especially if they are also marginalized in other dimensions, such as immigrants, ethno-cultural groups and the LGBTQIA+ community (Kidd & McKenzie, 2013). Ostrow et al. (2019) present the benefits of self-employment for mentally ill people, an alternative path to work that provides a more-or-less regular wage while (presumably) preserving their quality of life and social and economic inclusion.

We argue, however, that a deeper analysis and a systematic change are needed in order to reach a consistently better way of life for marginalized groups. A change that promotes emancipation, empowerment and cooperation as a modus operandi of everyday social interaction, which is very difficult -if not impossible- in a capitalistic-only society, where individualism and the heroic model of the "self-entrepreneur" are venerated. This change, we defend, comes from solidarity models of living, working and interacting. In this sense, our paper adds to the literature by reinforcing the importance of SEV to the social and economic (re)inclusion of people with mental health issues, and by addressing the role of financial literacy in their active participation and empowerment.

Therefore, based on our previous discussion about situated financial literacy, our proposal in this case study was to understand the needs of SEV worker-members in terms of financial and accounting knowledge, and to develop a program that could support these population in their practices. In the following section, we describe the methods adopted, emphasizing the path followed in order to (i) have a better grasp of their needs, (ii) design a financial education (FE) program, (iii) implement such a program, and (iv) evaluate the experience in the light of the needs it was designed to fulfil.

Methods

In this case study, our initial aim was to analyze the experience of two SEV - O Bar Bibitantã and Ponto Benedito de Economia Solidária e Cultura- engaging altogether mentally ill individuals and mental health workers and researchers. Both ventures have the goal of ensuring positive results from three different, but complementary, points of view: (i) from a social perspective, building on an inclusive ambience, respecting individual rhythm and processes, regaining their identities as worker-members through productive work, wealth and health; (ii) from an economic perspective, being self-sustainable and financially inclusive, reaffirming a diverse economic and business model; and (iii) from an accounting perspective, through the development of accounting technologies specifically designed to address the challenges and needs of enterprises like those: healthily crazy businesses.

Realizing that serious issues regarding (the lack of) accounting literacy and financial education were present on the day-to-day activities of both ventures, our focus shifted to analyzing the experience of designing and implementing a FE program planned to support the enhancement of accounting literacy, expecting that the worker-members engaged in those ventures would participate equally in accounting and financial discussions and decisions regarding the business. Our analysis was guided by an action research (AR) framework, following the steps of the AR cycle, namely: select a focus; collect data; analyze and interpret data; take action; reflect; continue/modify (Gall et al., 1996).

The implementation of the FE program was meticulously planned during a series of meetings, after which a three-classes course resulted, covering the following contents: (i) introductory personal finance notions (value of money in time, inflation, interest rate, personal investments and credit); (ii) personal financial planning (spending and saving money, personal expense control); and (iii) accounting notions (expenses and revenue, profit and loss, price, cost allocation, budget, overhead).

After designing the program, we started to prepare the contents and learning activities for each lesson. To reflect about the experience and outcomes of the FE program, we gathered our chain of evidence by registering and documenting every step taken in the process of planning, implementing and discussing the experience, from day zero to its end. So, for instance, every meeting in the planning phase was registered. Table 1 briefly describes each step of the process and how it was registered for later analysis and interpretation.

Table 1 Description of the planning and elaboration of the financial education program.

| Step | Description | Documentation | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meeting with Ponto's coordinators | This meeting had the aim of discussing learning goals, delivery strategies, target audience, and learning outcomes. One meeting. Duration: 2 hours. | Recording and note taking | September 2016 |

| Meetings with financial education program team members | These meetings were aimed to reflect upon previous steps outcomes and plan next steps. Three meetings. Duration: 1 hour to 1 hour and 30 minutes, each meeting. | Notetaking and diary | October 2016 -November 2016 |

| Final meeting to design the program | In this meeting, based on the outcomes of all the previous steps, the program was discussed and designed. One meeting. Duration: 4 hours. | Flipchart, developed through a design thinking methodology | November 2016 |

| Post-program meeting | In this meeting, the FE team discussed main takeaways and outcomes of the program. Each member shared their points of view for highlights and nadirs. One meeting. Duration: 5 hours. | Note taking | December 2016 |

Source: authors.

As a strategy for analysis, departing from the theoretical framework, we engaged in a reflection about what we have learned from the field. We considered the three FE program lessons as the main field of study. All the lessons were recorded in audio or video. At least two members of the FE team facilitated each lesson, which allowed us to have complementary stakes of each of our sessions. This material, recordings and personal perceptions and notes were key in the post-program analysis.

The comparison of what was planned (in terms of content and learning activities) and the actual classes, confronted with the literature review, was our focus of analysis. The feedback from participants came from their engagement in each lesson. Although we can say there were clearly different patterns of participation, we were all surprised by the level and quality of each participation.

Therefore, after realizing that the accounting and financial literacies that we, as scholars, considered unique and superior to all others were far different from the accounting and financial literacies by the FE program participants, we came to the conclusion that this study focus needed to shift once more towards a critical perspective on accounting.

Analysis and discussion

The case

This FE program is part of outreach and research efforts which brought together two faculties, the Nursing School and the School of Economics, Business and Accounting, both at the University of São Paulo, and a Centre for Psychosocial Care (CAPS) in the city of São Paulo.

The CAPS functions as an incubator for O Bar Bibitantã, which is a cooperative venture that organizes gastronomical events and has the premise that work is a consolidated right, a social inclusion instrument, and "a space for sharing and production of meaning and of objective and subjective values" (Ballan & Aranha e Silva, 2016). For them:

O Bar Bibitantã is an entrepreneurship strategy for producing and consuming things, producing and consuming meetings, producing and consuming knowledge, producing and consuming care and affection, values that aggregate themselves into the products of solidarity work. (p. 188)

The cooperative started in 2006 as a buffet service, based on the genuine Brazilian cuisine as a cultural value. It is a SEV, part of a mental health network, comprising different initiatives with the same goals. Currently, O Bar has approximately 16 worker-members, almost all of them bearers of some kind of mental illness - all of them are also patients of the CAPS. To get an appraisal of the importance the O Bar has to its members, one of its members explains, on her own words, that (Instituto Consulado da Mulher, 2014):

Some events that we organize are attended by 200 to 300 people and, in the end, they ask us if we had bought the canapés from somewhere else. And then we reply: 'No, we did it all!' They insist: 'And you, who are you? What do you do?' And I say: 'I am Celia. I am a cook. I am a CAPS user and I work at the O Bar Bibitantã.' (para. 1)3

Thus, O Bar becomes part of a reconstructed identity, an identity of someone that is not only defined by their mental illness, someone who is capable and productive. Zambroni-de-Souza (2006) describes this process of 'rebuilding an identity.' He explains that, when working, an individual is convened not only with his/her force but also with his/her workforce. So, s/he has to employ his/her productive capacity to complete a task, to get the work done, to produce something for him/herself and also for others. To attain this goal, an individual uses her/his resources, capacities and skills, and has to choose a manner or a way to complete that task. Therefore, following Zambroni-de-Souza (2006), there is a need for a new conception or way to restructure the "prescription" and fulfil the task. When working (or performing any other activity), there is a need for self-management, a re-singularization, that builds (or rebuilds) one's competence, one's health, one's identity, opening paths for someone with mental illness to abandon the historically construct identity of an incapable person, thus improving our health and walking towards emancipation.

Zambroni-de-Souza (2006) states that work experiences involving people with severe mental illnesses challenge a widely spread point of view constructed in the history of psychiatry that those people cannot work, because they are incapable of adapting themselves to the requisites of any production or service, leading to isolation and social and financial exclusion.

Ana Aranha, Nursing Professor at the University of São Paulo and one of O Bar's co-founders, extends this testimony about O Bar using accounting-like terms (Aicó Culturas, 2011):

Our biggest asset is not physical or material. Our biggest asset is exactly the workers that have high capacity and desire to work and are the owners of the few means of production that we have. [It is] the work as a human right and as a way of work organization that does not produce excluded members and does not prevent vulnerable people access [the right] to work.

Nothing here is naive, everything here has a meaning, has a reason. It is work, work, human labor. What do I want? What should I do? In which way do I do it? With which purpose do I do it? (03:38)

Following the same path, in September 2016, Ponto Benedito Calixto de Economia Solidária e Cultura was inaugurated. Ponto is a fair-trade point that reunites other solidarity economy cooperatives engaged in mental health promotion, such as O Bar. These ventures are encouraged to sell their goods (produced elsewhere) at Ponto, under a 10% contribution margin (overhead) to Ponto's maintenance. Another purpose of Ponto is to develop cultural activities organized by solidarity ventures or work and art groups, such as film exhibitions, musical plays or seminars.

All the people working at Ponto have some degree of mental illness, although there are also a considerable number of volunteers contributing to Ponto's maintenance and activities. Ponto is a unique experience, unifying teaching, outreach and professional formation, while enabling people with mental health issues to regain their right to work and produce. In the excerpt that follows, Ana Aranha introduces the idea behind Ponto (Teixeira, 2018):

The experience [that Ponto Benedito] has shown us that the only way of organization of work feasible for these people [mental health public services' users] is exactly work [as it is organized in] this experience, in which it is not competitive nor excluding, not organized in a way that prevent access of these individuals to both production and commercialization activities.

[...]

Ponto allows these experiences to people who usually do not have access to them. (00:49)

In this context, O Bar and Ponto started to be aggregators; to answer to each person's real needs of producing and consuming material and immaterial goods; to cooperate; to allow more voices to be heard; to be democratic; to search for the reestablishment of the potentialities funded in the recognition and respect of differences; to be "collectives of identity" with the mission of producing and reproducing real economic gain; to admit and encompass individual pace and way of being; to (re)affirm weirdness and differences, equating ways of living as one truly human dimension in social relations; to face with radicality the dispute (or the lack) of ideas; to sustain the difference on knowledge without denying it and placing this knowledge for analysis, making it available for the collective.

At the same time, both ventures are places to make money! This way, the product of the work by all those involved needs to have value, to be good, to be desirable, and to be competitive for its quality. Those characteristics entail the notion of work as a transformational force or potency. In other words, work that produces emancipation, the amplification of potentialities, human capabilities and non-alienation. It is a dialectic act of transformation because when workers transform raw materials into food, they are also transforming themselves into someone capable of doing and producing food.

In order to represent the perception of workers, we bring testimonies in which they reflect on their trajectories in the SEV. Celia, one of the FE course attendees and the head cook at O Bar, remembers her first event as a worker, which was attended by 150 invitees:

In my first event as an intern at O Bar, even in a breakdown, I cooked all that was needed. I did many different dishes... Eggplant canapé with raisins. When the event ended, the lady who hired us opened her wallet and gave me 200 reais, as a tip. We shared it among all. But as I was an intern, I should not be paid. The group thought it was not fair and I already got paid in the first event. Until today, I am working at O Bar. I am the head cook and I feel proud. I even cry when I realize that our Bar is growing, expanding.

In a video about O Bar's trajectory named "O Bar Bibitantã: trabalho que transforma [O Bar Bibitantã: A transforming job]", Luciano, another O Bar worker, says: "I would like to work like this, arriving at the end of the month, and say to my wife and daughter: 'This is the money that daddy has just received.' (Aicó Culturas, 2011, 00:19)

Although in an ideal situation all the cooperative members are equally participative or, at least, present and interested in general meetings or assemblies, or at taking decisions about an event planning and organization, it was simply not the case for O Bar nor for Ponto when the discussion was somewhat related to accounting (e.g. cost estimates, pricing, cost and surplus allocation, etc.). In these cases, the decisions were made almost entirely by non-mentally ill volunteers, such as CAPS workers. This lack of participation in financial and accounting-like discussions and decisions was one of the major complaints the FE team received, and it was perceived as an important area for improvement. Therefore, we discussed internally the necessity of designing a FE program to SE worker-members, keeping in mind the words of Aranha e Silva (2012):

For an outreach to be consistent and produce praxis, it needs to be generous, broad, and in fact to extend to the service, to the users of the service, and to the necessities of the service; to be humble when facing flaws, persistent in the search for answers, and to produce not a cultural invasion, but co-'labor'ation. (p. 3)

So, we aimed at designing, developing and implementing a FE program with the learning goal of supporting the attainment of an accounting and financial literacy that would ultimately allow both O Bar and Ponto's worker-members to feel confident and autonomous to participate actively in accounting-like decisions.

Implementing the program

All the classes were ministered in a space conceded by Associação Vida em Ação, an NGO that supervises Ponto and O Bar. It is the same space where Ponto is located.

In this first class, held in November 29, 2016, after a brief introduction, the first topic covered was the relevance of FE for our personal lives and the consequences of the lack of this subject in school curricula. It was agreed that the consequences are profound in adult life, especially in a developing country like Brazil, which has faced challenges such as hyperinflation and still has high interest rates. One of the attendees, for instance, presented some real-life examples she went through, where saving money and minding the prices were imperative, such as Black Friday and the artificial discounts given on goods. She called it "Black Fraud."

The second class took place in December 3, 2016, and was aimed at exploring some essential mathematical and financial concepts for running a commercial venture. Some of the topics covered in this class were percentage, interest, simple and compound interest rates, inflation, savings accounts and comparison between traditional banking institutions and solidarity economy banking systems. When asked about what percentage means, one of the attendees answered that it is "a part of something," while another said that "for example, if something is full, it is one hundred percent." The instructor gave an example from Ponto itself: 10% of its income on sales is reinvested on the venture (overhead). And then he asked: "So, if Oficina dos Anjos earned R$240 in November at Ponto, how much should go to it?" Without hesitation, the three attendees answered R$24. Their answers were also quick and correct when the examples were with percentages of 20, 30 and 50%. Similar situations were observed regarding interest, simple and compound interest rates, inflation and savings accounts. It was evident that the attendees already had a tight grasp on these concepts, although they did not necessarily know how to formally describe them as we would do (and value) in our accounting culture. It was clear to the instructors that they had the practical knowledge, even though they did not feel confident in using the accounting terminology. In our reflection, this is an example of Bay et al. (2014) concept of situated financial literacy, as it clearly showed that the worker-members had financial competence, although were not able to reproduce the financial vocabulary in its narrow sense.

The first topic of the last class, held in December 10, 2016 was revenue, described as the money received for a product sold or a service provided. The attendees were fast in giving some real-life examples of this kind of economic event when asked. The same was observed on the next topic, expenses, when there was a brief discussion about whether there would be expenses related to Ponto, since the building where it operates is free of charge and, therefore, the solidarity ventures within Ponto do not have any expenses related to rent. One of the attendees raised an interesting question, arguing that there could be some kind of implicit expense, perhaps not in material terms, but instead some kind of "favor" owned by Ponto, or some immaterial benefits it should be "charged for." The topics followed in sequence were profit/loss, surplus and surplus allocation. These last two topics have an important role in the vocabulary of the SE. As mentioned before, in SEV, the surplus is allocated among all the associates that participated in its production. We saw during the lesson that there are two ways of allocating surplus: equally, i.e., all associates receive the same exact amount of money; or, more usually, proportionally, i.e., each associate receives an amount equivalent to the number of worked hours (or worked days, or per event, etc.). This is a decision that should be made in assemblies. One of the attendees stated that this is the reason why he thinks a cooperative is more ethical than a capitalist company, since its decisions are taken exclusively in assemblies where all associates have the right to vote, disregarding the concept of hierarchy. According to Shearer (2002), such a system is impossible in a capitalist economy or venture. This reinforces the perception of SE as an alternative to capitalism, as discussed by Singer (2002), Neamtan (2002), Ballan (2010), and Lussi and Pereira (2011).

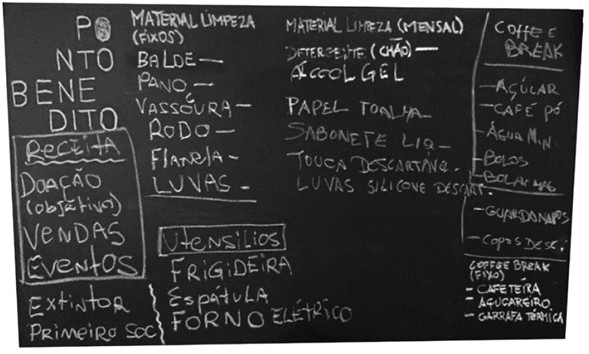

In the very last activity, attendees were asked to design a 'monthly revenue and expenditures blackboard' to be exposed in Ponto, making its accounting transparent to everyone and anyone. They seemed excited to do that. Figure 1 shows a digital reproduction of the resulting blackboard designed collaboratively during the last session. The original photo is annexed to this article.

Source: authors.

Figure 1 The monthly revenue and expenditures blackboard as designed at the end of the third lesson (digital reproduction for publication purposes).

The blackboard was a concrete outcome of the FE program, and a demonstration that we kept our promise to put financial education into action, through our strategy to build on daily experiences and needs of Ponto and, moreover, in doing it, being guided by the principles of SE. It also demonstrates for us, in our reflection, that financial and accounting literacy is relevant when it expands your capacity of using this insights. Therefore, financial and accounting literacy is what you do with it (Bay et al., 2014).

Another example of a good and handy outcome of the FE course was presented by one of the attendees, Ana Paula, a female worker at both Ponto and another SEV, called Oficina dos Anjos. Ana Paula says that since childhood she has loved mathematics and dealing with numbers in general. So she naturally became the main accountant at both SEV. She, however, was dealing with some trouble regarding Ponto's accounting necessities, since, due to the nature of its operation, a lot of new and intricate information had to be registered, elaborated and translated into numbers in an organized and understandable way. Ana Paula then, after the FE course, in order to deal with these obstacles, developed and proposed a new bookkeeping method, which, according to her:

[has the advantages of] being able to inform each [partner] venture the prices of items sold and how much is owed to them; of organizing the work; and preventing people from getting lost, without knowing where the money is going. [...] I started to use this method after the [financial education] course. It was necessary in order to prevent people from getting lost. (direct quote from Ana Paula's testimony)

It is worth to note that this organized and easy-to-read bookkeeping method developed by Ana Paula is used to this day (2021) at Ponto, and is affectionately called "Ana Paula Method" by all.

Figure 2 shows the digital reproduction of a real example of how Ana Paula Method was applied in Ponto's July 2021 bookkeeping. It reports (i) the date, (ii) who were present at Ponto during that day, (iii) the quantity of items, (iv) the name of the item, (v-vi) the price of the item (column 5 for cash, column 6 for debit card); (vii) the name of the venture responsible for that item, (viii) relevant printed receipts attached to the page, and (ix) relevant observations. The original photo is annexed to this article.

Source: Ana Paula, Ponto Benedito de Economia Solidária e Cultura. Reproduced with permission from the author.

Figure 2 Ana Paula Method in action (digital reproduction for publication purposes). This page represents one-day sales at Ponto (July 31, 2021). Sensitive information was censored.

In our reflection about the experience, it became evident that we had fallen into the trap of our own implicit preconceived implicit ideas about how much the mentally ill can accomplish. How powerful is the reproduced discourse? How does it blind us from imaging and embracing other possibilities? How can we free ourselves of reproducing stereotypes and, through this, imposing a single story on someone? In the process of searching for the answers to these questions, various lessons have emerged from the field.

Concluding remarks

In a nutshell, the takeaways from this experience were (i) the importance of abandoning preconceived ideas of mental illness and relying on sharing experiences and participation; (ii) how real-life struggles are a source of knowledge usually better than theoretical classes, something that we call "learning by doing," a concept deeply studied by Brazilian educator and philosopher Paulo Freire (Freire, 2003); and (iii) the relevance and power of the situated and contextual financial literacy, which concerns what we do with our literacy (Bay et al., 2014). In that sense, activities based on the real needs and specifics of solidarity economy businesses were especially fruitful and engaging.

Lessons from the field

We sought, with this case study, to provide a critical reflection on the possibilities of solidarity economy and financial/ accounting literacy as tools, actions and strategies towards a health promotion strategy in order to empower individuals, so that they can (re)write their stories and give society an account of themselves other than their mental health illness. Our experience was built upon designing and implementing a financial education program targeted at SEV. Three lessons were learned from this experience.

The first outstanding aspect for us was the difference between how we intended to drive the classes and the real outcome we obtained. When we were at the planning phase of the FE course, our intention was to plan lessons that were simple in language and concepts, thus levelling the financial knowledge of participants. But we fell flat on our faces: what we realized was that all of them already had some accounting and financial knowledge we didn't really expect them to have, such as intangible assets, rights for patents, how to price knowledge, costs of inventories, the notion and concept of royalties. Here fits a critique to ourselves as researchers as well as human beings: in our good intentions to empower mentally ill individuals through an educational strategy we fell on the trap of the dominant discourse typically aimed at this group, allowing ourselves to have only the stereotypical point of view of constructed images and history of people with mental illnesses (Zambroni-de-Souza, 2006), and to assume they are less capable of working, learning and having any kind of technical or specialized knowledge. We assumed, even if unintentionally, that people are formed by only one story. And as the feminist Nigerian writer Chimamanda Adichie (2009) said on her TED speech:

Show a person as one thing, as only one thing, over and over again, and that is what they become. [...] The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story. (09:28)

In our intention to make relations of power less unequal, we reproduced and perpetuated this by hearing and acknowledging only one story about them. Adichie (2009) continues by stating that:

Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person. The Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti writes that if you want to dispossess a people, the simple way to do it is to tell their story and to start with, 'secondly.' Start the story with the arrows of the Native Americans, and not with the arrival of the British, and you have an entirely different story. Start the story with the failure of the African State, and not with the colonial creation of the African State, and you have an entirely different story. (10:05)

Likewise, if we choose to see the story of people with mental illnesses not with the notion that they are all just "crazy people" and, therefore, not able to work and learn, but instead considering that they may have mental disorders but also have daily struggles, life objectives, and are people with as much capacity as anyone given the same amount of stimulus, we will have a very different story.

Fortunately, there are a lot of successful examples to support this wider view, such as the testimony we saw before from Celia, one of O Bar's members: "In my first event as an intern at O Bar, even facing a mental breakdown, I cooked all it was needed. I did many different dishes [...]". She also stated that she used to chew her fingernails until they bled due to high anxiety and persecution complex, but nonetheless she attended O Bar's events using gloves to hide the wound marks on her hands. Being a CAPS user at the same time she was hired to work was a great progress on her trajectory. It is an example, out of many others, that shows us that a multiple-sided rich story may be told instead of the old, narrow and stereotyped ones. Stories that show that a mental illness does not prevent anyone from being capable of living in a society or working wherever s/he wants, taking the responsibilities needed, even during mental breakdowns. For that, however, it is essential the cooperation and willingness to help from everyone involved. That's the advantage of cooperatives and solidarity economy ventures.

Based on the above, the First Lesson is: it might be a utopian goal to free ourselves from preconceived ideas, but to reflect constantly on our actions, practices and discourse is an exercise we should all do in all realms of our lives. The perpetuation of old and blind prejudices and the lack of attitude to break people down is what makes them even more present (Eagleton, 1976, cited in Ogbor, 2000), thus preventing any possibility of social change.

The second topic comes from the fact that, during the planning and implementation of the lessons, the intention was to teach attendees some financial education concepts, such as the value of money over time and how to organize not only their ventures' finances, but also their personal finances. Lusardi and Tufano (2009) indicate that there is a relationship between an individual's knowledge on financial literacy and his/her behavior. For example, these authors showed that illiterate people are more likely to be in debt. And if we consider individuals with mental illnesses, there are a lot of other issues (like breakdowns) that may interfere with their financial abilities, even if they have financial knowledge. Considering that, sessions were conducted in a form that encouraged participation, allowing participants to bring their own experiences and consequently making the classes more meaningful to them. When an individual adds knowledge with real-life struggles and necessities, they are more prone to overcome their problems and to prevent new and old mistakes. It helps them think over their actions and its purposes, and to come up with innovative solutions for their problems. It goes way beyond the simple development of mathematical skills or financial vocabulary (Bay et al., 2014; Stieger & Jekel; 2019).

Hence, the Second Lesson learned is: education as a strategy and action to empower individuals should be contextualized and meaningful to make sense, and built with the participation of all actors in order to make social changes possible. In doing so, (financial) education shall be seen as an act of empowerment and health promotion, breaking the barriers of traditional conceptions.

The third topic relates to the stance we first took on FE. When implementing the course, we applied the dominant understanding of what financial literacy is. Our intentions were to measure the level of financial literacy of the worker-members, to investigate the effects of financial illiteracy on their financial decisions, and, finally, to equip them with financial skills. The premise was that by being taught about finance and accounting concepts, worker-members would apply these insights to their practice automatically. Therefore, we were not considering the situational financiai literacy model, at least not intentionally (Bay et al., 2014). Drawing from the previous theoretical discussions, the specificities of the context (a SEV engaging people with mental illnesses and mental health researchers, students and scholars), and our purpose (helping worker-members attend to their identities and singularities), the situated model of financial education would have helped us to apprehend the complexity of the context and to better design our program upon their practices. But, as a result of our planning method, built after a discussion with O Bar's coordinators, we adopted a participant-centered teaching process with many moments during the classes to share experiences and work collaboratively on examples derived from their practices. Reflecting upon our strategy, it seemed to us that this was what made it possible to unintendedly migrate from a dominant model of financial literacy (during the planning and designing phase) to a situated model (during the implementation). Surprisingly, in our analysis this was what allowed us to "save" the FE program, making it fruitful; although it was one of the criticisms we have heard from the participants, stated as "too much participation."

Thereby, the Third Lesson is: financial and accounting literacy is what you do with it (Bay et al., 2014). Knowledge without a meaning applied in a real situation is sterile knowledge, it can't bear any fruit. On the other hand, a properly applied knowledge has flavor, it is a pepper that can spice up our living (and loving) experiences. Our contribution, then, is arguing that SEV are providing, through its way of functioning, a learning space for building situational and contextual financial literacy and, even more, to the development of accounting technologies. In this way, they can be understood as vehicles for a situated model of financial literacy, in which workers-members are asked "to reflect on their role in society and to consider the necessity of a practice in which financial competence is a given" (Bay et al., 2014, p. 41).

Contribution to critical accounting research

We believe that this work will help the academic community to realize there is much empirical, informal, and marginal knowledge that is distant from mainstream discussions, and, more importantly, that this knowledge is valuable and is produced by marginalized groups of people. So, we hope our study resignifies the understanding of accounting knowledge producers in other contexts (SEV) and by other actors (people with mental health issues). This work also builds on the strand of research initiated by Bay et al. (2014), arguing that SEV for mentally ill people can be seen as vehicles for developing situational and contextual financial/accounting literacy, in a way that broadens the emancipatory role of accounting.

Such a study is also a recognition, a validation, and a tribute to the popular knowledge teaching the technical knowledge. It is also a representation of the dialogical dimension of SE and of social, productive, and cultural inclusion policies.

SE is also a critique of the theories that are in place. This approach can be understood as a way of living life with a dimension of respect for the environment and for all forms of relationships. Thus, it can be understood as a form of critique that denies a certain logic, which is the logic of capitalism.

Contribution to solidarity economy practice and literature

SE is a system, or, as some of its practitioners say, a way of life based on the principles of autonomy, decentralization, trust, and understanding (of myself, others, and the community), providing emancipation and self-improvement. These are good-natured intentions that provide a horizon for SEV, but that often stumble upon a lack of operational knowledge -such as accounting knowledge-, an aspect even more pronounced in SEV composed by people with special needs. In order to surpass these challenges, SEV rely on networks formed by partner ventures and groups.

The financial education course proposed and conducted, which was exposed in this paper, intends to strengthen such a network and to ignite a spark of interest in accounting and financial literature in some SEV and its members. We believe that financial education has the potential to further empower SEV members with a mental illness, enabling them to reach even higher levels of independence from the common social modus operandi that negates their existence, and thus proving them that one does not need to be an academic or a white-collar worker to deal with relevant business processes.

This article also contributes to building knowledge in the intersection of three constructs seldomly seem together: solidarity economy, mental health, and financial education. By doing so, it criticizes dominant capitalistic discourses that tend to compartmentalize mentally ill people in mental health institutions, away from society, from business, and from success.

Future possibilities of research

This study had people with mental disorders as main actors, but similar conclusions can possibly be drawn by studying homeless people, transgender individuals, refugees, or drug addicts, and so many other groups excluded from their rights as citizens.

We hope that this article will encourage further discussion about what accounting is, who makes use of it, and whom it serves, so that financial and accounting literacy can be used to build a more equitable and just society, breaking down or weakening the barriers between scholars and the broader society.