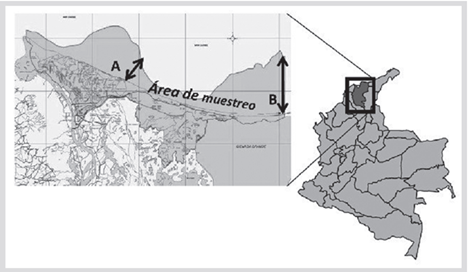

Vía Parque Isla Salamanca, located on the Colombian north coast (Magdalena Department), in the jurisdiction of the municipalities of Sitionuevo and Puebloviejo, is a protected area of strict conservation of the Colombian System of National Parks (Figure 1). It is bordered to the north by the Caribbean Sea, to the south by the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta and Caño Clarín Nuevo, to the east by the small village of Tasajera (Puebloviejo) and to the west by the Magdalena River (UAESPNN, 2004). The ecosystems of the Vía Parque include sandy beaches; however, the only study of fish fauna in the marine area, was carried out in 2006, when the Special Administrative Unit of the National Parks System adopted the SIPEIN (Invemar’s Fisheries Information System) as a tool to assess the pressure of fishing on hydrobiological resources, and to design management and conservation measures.

Figure 1 Vía Parque Isla Salamanca (shaded sector) and the sampling area A-B (coastline towards the sea). Sourceː file VP Isla Salamanca.

On the other hand, the marine and coastal areas are of great diversity, making them one of the most productive ecosystems on the planet (Eichbaum et al., 1996). In Colombia, fish biodiversity is one of the largest in South America ( Polanco and Acero, 2020), but the lack of records at the species level and the discontinuity and scarce geographical coverage of fisheries data (Chasqui et al., 2017) makes it necessary continue studying and monitoring marine fish, as well as assessing multispecies stocks (Duarte and Schiller, 1997). This information allows directing specific actions and management proposals towards the conservation of coastal marine fish species (Manjarrés, 2004).

The little knowledge of the marine area of the Park as well as the lack of records on fish biodiversity in the Colombian Caribbean, lead this study, in order to know the assemblages that occur in the VP Isla Salamanca. Monthly catches were evaluated (between September 2006 and April 2007), obtained with a beach seine known as chinchorro (total mesh lengthː 500 m, mesh eye 7.5 cm, total length of the cod-endː 8 m, cod-end mesh eyeː 5.5 cm). Twenty-five (25) hauls were made with artisanal fishermen from the village of Tasajera, who had the necessary experience in using the gear and knowledge of the sampling area (Figure 2). This method is the least selective fishing in the area, and guarantees a greater representation of species and individuals of different sizes.

Captured individuals were counted and identified using the guides of Cervigón et al. (1992) and Carpenter (2002) at the sampling site, and the taxonomy was later revised according to Robertson et al. (2019) and Fricke et al. (2020). The fish that could not be identified were collected in hermetic plastic bags and transported to Invemar for identification in the laboratory.

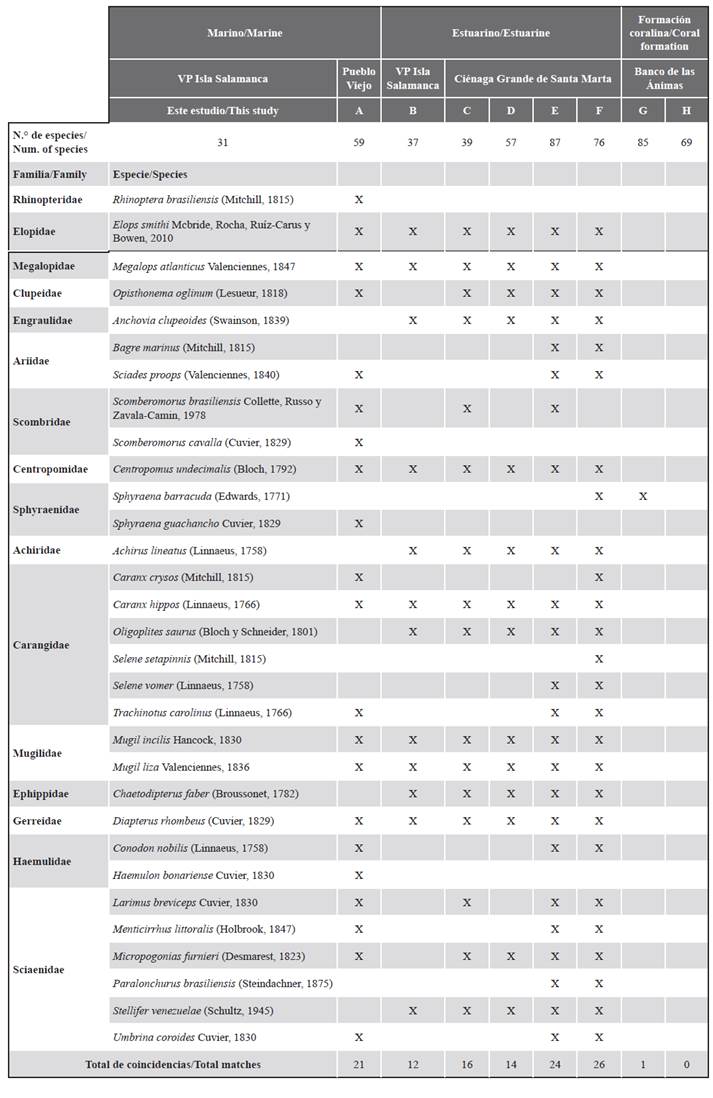

A total of 10 114 individuals were collected, belonging to 16 families and 31 species. Families Carangidae and Sciaenidae were the better represented (Table 1). The richness found in this study is lower than that reported in adjacent marine waters (59 species; SEPEC, 2019), from the estuarine area (87 species; Santos-Martínez and Acero, 1991), and from the Banco de las Ánimas (85 species; Acero and García-Urueña 2020). Differences may be explained by the frequency and time spam of samplings, as well as by the methodology used in relation to the evaluated ecosystem, demonstrating the ecosystem heterogeneity in a part of coastal-marine area in the north of the Department of Magdalena. The greatest coincidences were with the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta (26), evidencing an important diversity, due to temporary variations in abundance and composition of species targeted by fishing, linked to global climate variability, and associated with changes in salinity (Invemar, 2019).

Table 1 Fish species registered in the marine area of the VP Isla Salamanca, and comparison with studies adjacent to the study area: A) SEPEC (2019). B) Zubiria et al. (2009). C) Rueda and Defeo (2003). D) Sánchez and Rueda (1999). E) Santos-Martínez and Acero (1991). F) Invemar (2019). G) Acero and García-Urueña (2020). H) Navas et al. (2017)..

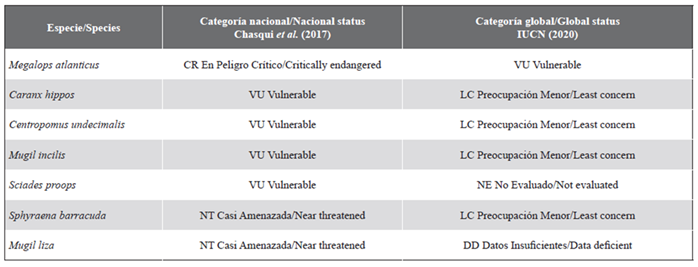

Seven fished species are included in the Colombian Red Book of Marine Fishes (Chasqui et al., 2017); five of them with some category of threat, and only one of them considered Vulnerable globally (IUCN, 2020; Table 2). Threat identification criteria vary in regional, national and global scales, taking into account anthropogenic factors to which fish populations are being exposed. In the case of marine species, different pressures have been mentioned, such as resource overexploitation, use of inappropriate fishing gear, chaotic developments in coastal areas, direct sewage discharge into the sea, increase in maritime traffic, excessive and unsustainable tourist activity, and lack of clear legislation on coastal marine issues, among others (Chasqui et al., 2017).

Table 2 Species registered in the marine area of the VP Isla Salamanca and included in the National Red Book (Chasqui et al., 2017) and the global Red List (IUCN, 2020).

These results contribute to take management proposals towards the protection of hydrobiological resources in the marine area of the Vía Parque. Some of them are articulate conservation measures for mangrove areas adjacent to the marine area of the Park, proposing studies of distribution, biology and ecology of fish species, establishing closures and minimum catch sizes for non-commercial fish species, and developing interinstitutional management to carry out environmental education; the mission and conservation management for which this protected area has been created will be then fulfilled.

text in

text in