Introduction

Writing is a productive language skill that has traditionally been considered an individual activity in the field of education, involving only the author (Kroll, 2001). According to this view, when an individual expresses their ideas in writing, they have to make decisions based, for example, on their own linguistic knowledge on relevant topics, grammar, vocabulary, levels of formality, types of texts, among others (Briesmaster & Etchegaray, 2017; Craig, 2013). In today’s classrooms as well as in the business context, writing is treated as a social endeavor because the production of a text with others helps writers to evaluate their language use and receive language input and feedback from peers (Fernández Dobao, 2012). In fact, collaborative work, whether in pairs or larger groups, has increasingly been adopted in the classroom as joint efforts make it possible for leaners to achieve a common and more effective goal (Johnson & Johnson, 1999; Rollinson, 2005).

Collaboration offers other advantages, such as improving students’ interaction in the classroom, reducing anxiety levels associated with individual work, increasing self-esteem, improving social skills, developing a sense of cooperation and community, and facilitating and optimizing the learner’s personal and academic growth (Barkley, Cross, & Major, 2005; Elola & Oskoz, 2010; Hunzer, 2012). In the context of language teaching, collaborative writing is defined as joint production or co-authorship of a text by two or more writers (Storch, 2011). Research suggests that collaborative writing is useful for helping learners to improve their written performance in terms of fluency and accuracy as well as for their interpersonal skills, enabling them to work more effectively with others (Fernández Dobao & Blum, 2013; Pardo-Ballester & Carrillo, 2015).

Collaborative writing activities may be reinforced by using technology in learning scenarios even more so today, when students can go beyond just reading and retrieving information to creating and sharing information (Lomicka & Lord, 2009). In fact, there has been a shift from Web 1.0, which involves a one-way portrayal of information on static webpages, to Web 2.0, characterized by collaboration, participation, and information sharing by facilitating interaction among users, the latter of which is fast becoming a permanent component of people’s lives (McBride, 2009). In Web 2.0, users utilize technology for interaction, collaboration, networking, and entertainment through blogs, wikis, social networking tools, and multiplayer games (Warschauer & Grimes, 2007). A number of studies have already suggested that technologically enriched environments encourage language learning because they are more motivating and psychologically comfortable for learners (Blake, 2000; Kessler, 2009; So & Brush, 2008). From this viewpoint, by working in such environments, learners are given authentic and realistic input and, at the same time, an opportunity to experience a process of interaction and negotiation of meaning as they communicate, whether synchronously or asynchronously (Dudeney & Hockly, 2012; Herrera, 2017; Ubilla, Gómez, & Sáez, 2017). Owing to technological advances, it is now possible to write texts collaboratively at a distance yet simultaneously while producing intelligible output as learners negotiate meaning with their peers or tutors in processes mediated by technology (Chapelle, 2003; Lamy & Hampel, 2007; Warschauer, 2005).

Moreover, recent research suggests that online collaborative writing can be beneficial for second language (L2) learners as it offers them different opportunities to practice both their communicative skills and the target language in an appealing and non-threatening environment (Sun & Chang, 2012; Warschauer, 1997). In this line, an interesting development in education has been the adoption and adaptation of free mainstream cloud-based file storage and synchronization services such as Google Drive for collaborative writing. Tools such as this allow users not only to store files on servers but also to synchronize them across devices, and share them online. What is more, multiple users may create and edit a single file synchronously or asynchronously, thus making collaborative writing possible even at a distance.

Furthermore, file storage services such as Google Drive may be used together with blogs to provide language learners with an instructed scaffold for a more enriching learning experience. In fact, research suggests that when students work collaboratively while supported by technology, they feel their contributions are valued, and the quality of the product improves (Augar, Raitman, & Zhou, 2004; Borrell, Martí, Navarro, Pons, & Robles, 2006; Brodahl, Hadjerrouit, & Hansen, 2011; Choy & Ng, 2007; Chu & Kennedy, 2011; Kessler, Bikowski, & Boggs, 2012; Ubilla et al., 2017).

Bearing in mind the aforementioned information, this study is a step forward in understanding pre-service EFL teachers’ perceptions regarding collaborative writing because it has added the component of an online file storage and synchronization service to the blended environment, thus further contributing to the growing body of empirical research on online collaborative writing. For the purposes of this study, collaborative writing is a learning experience that promotes both individual and group responsibility and relies on the distribution of tasks and roles with the aim of achieving the common goal of writing a text (Shehadeh, 2011) in argumentative form, that is, written discourse whose purpose is to persuade the recipient (Parra, 2004). Dialogue, negotiation, and interaction are fundamental in this process (Gee, 2012). The pre-service EFL teachers who were the study subjects were in their final year of their university training program prior to their professional practicum, and they worked on the joint production of an argumentative text. As such, the present study adheres to the traditional structure of an argumentative text composed of a thesis, an argumentative body, and a conclusion (Ducrot, 2001; Spicer-Escalante, 2005; Toulmin, 1993).

The overall objective of the study was to unveil the perceptions and self-assessment of senior-year pre-service EFL teachers in a Chilean university in the context of a collaborative writing intervention in English. Within this framework, the following research questions were formulated: What perceptions do Chilean pre-service EFL teachers hold of their collaborative work when writing argumentative essays in English? What are the results of Chilean pre-service EFL teachers’ self-assessment of their collaborative work when writing argumentative essays in English? What is the relationship between Chilean pre-service EFL teachers’ perceptions of a collaborative writing intervention in English and their self-assessment of their performance?

Theoretical Framework

Writing is conceived as a complex process in which different factors interact, including the writer(s), a context, an audience, objectives, idea development, drafts, and the elaborated text. This process allows for the growth of intellectual capacities, such as analysis and logical reasoning, and constitutes a valuable instrument of reflection through which one can maximize their personal development and thus influence the world (Cassany, 1999).

Writing in the mother tongue (L1) and writing in an L2 involve certain differences. According to Gilmore (2009), writing is a complicated process for native speakers of any language, but when it comes to writing in an L2, learners encounter even more difficulties. The main difficulties in L2 writing involve personal writing processes, such as language use, coherence and cohesion, as well as preferences in organizing texts, such as writing own voice and organizing own ideas and those selected from sources. The main factors behind L2 writing difficulties include lack of previous writing experience, deficient knowledge about writing conventions, and teacher expectations (Gilmore, 2009). According to Silva (1993), writing in an L2 is linguistically, rhetorically, and strategically different in important ways compared to writing in an L1. These differences may include the following: (a) different linguistic skills and intuitions regarding language, (b) different perceptions of the audience and the author, (c) different writing processes, and (d) different preferences for organizing texts.

Returning to a more general sense, writing a text involves at least two dimensions: content (what to say) and rhetoric (how to put it into words), both of which involve decisions not only in relation to how to interpret and create ideas but also how to present them. If we focus on the content dimension, research in the area suggests that the writer should perform certain processes that help them to build up information (Cassany, 2000; Kellogg, 2008). These include: 1) developing ideas, 2) consulting external sources to improve the text, and 3) linking this new information with what is known to build new knowledge (Briesmaster & Etchegaray, 2017). Concerning the rhetorical dimension, it is suggested that the writer should create, interpret, and reconstruct ideas, considering the communicative functions and characteristics of the text or texts in question by using textual and grammatical skills (Van Dijk, 1983). This will allow them to adapt a specific style, organization, and linguistic register according to the characteristics of the target text (Badger & White, 2000).

A process-based view of writing lends itself to a student-centered approach that seeks to achieve autonomy in the language learning process (Badger & White, 2000; Brandl, 2002; Flower & Hayes, 1981; Rada, 1998; Topping, 1998). To that end, not only is the teacher’s guidance taken into account but also students’ previous experiences with the writing process and their present and future needs. The aim is to gradually achieve both independence and self-confidence in relation to what they write.

Furthermore, the process-based view of writing encourages students to explore an issue through writing as well as discussion and reading (Brandl, 2002; Falchikov, 1995; Rada, 1998; Topping, 1998). From this perspective, rather than emphasizing accuracy and structure, what matters is how the writing is developed and the message that is communicated. A hallmark of this approach is the use of a peer tutorial through which a tutor helps another language user become a better writer by guiding and supporting them in the production process (O’Sullivan & Cleary, 2014).

Collaborative writing focuses on the entire process of writing a document through a shared effort (Wigglesworth & Storch, 2009). It is a social process where learners face conflicts and negotiate to reach consensus. Conflict is seen as discussion between two or more people in disagreement over a topic, such as goals, behavior, points of view, or opinions (Shantz, 1987; Tocalli-Beller, 2003). In this context, conflict is not seen as negative but rather as a productive critical thinking activity to find consensus. In this light, conflict management should be taught and monitored if the goal is to help improve collaborative work and turn it into a benefit for learners, as it may have a negative effect on performance if left unattended. This perspective is similar to activity theory (Engeström, 1987, 2001), which poses that, when individuals perform collective activities to achieve a goal, these activities are mediated by community members who share different viewpoints and interests. This may help students develop skills in planning, drafting, periodic and collaborative review of writing, and knowledge of language, context, and the target audience (Derry, 1992). To a certain extent, it coincides with the view of writing as a social activity, in which learning with others also helps individual learning by developing cognitive structures and interactive skills (Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1987).

Working collaboratively in the production of a text offers opportunities for learning that promotes the negotiation of knowledge (Kessler, 2009; Shehadeh, 2011). Learners can execute discussions in order to reach an agreement regarding the meanings of concepts, their interpretations in the context of the learning task, or solutions to problems. Moreover, the learning outcome of collaborative tasks goes beyond the product of the task itself, leading to active exploration and the construction of debate opportunities during the negotiation process, especially when learners are developing skills in an L2 (Dillenbourg & Baker, 1996).

Collaborative writing skills are predominantly relevant in academic settings, and they are an important prerequisite for the extensive coauthoring that occurs in most academic and workplace contexts (Bunch, Kibler, & Pimentel, 2012; Jones, 2007; Koehler, Bloom, & Milner, 2015). In addition, they are essential not only for accessing and participating in an academic community but also for contributing to the knowledge-building process in scholarly disciplines. Therefore, educators have integrated collaborative group work as a core component of instructional strategies and curriculum standards across multiple disciplines.

Collaborative writing has also been defined as joint production or co-authorship of a text by two or more writers (Storch, 2011). However, it is not just a question of subdividing tasks and group members individually composing their own texts. It involves sharing copyrights, reading texts written by peers, adopting the roles of co-writer or co-editor, all in order for the group members to help one another produce higher quality texts. Collaborative writing helps students to develop strategies for delivering feedback to peers (for in-depth analysis of this complex phenomenon, which is well beyond the scope of this study, see Hyland & Hyland, 2019, and Yu & Lee, 2016) because reviewing and evaluating peers’ texts is part of the collaborative process (De Graaff, Jauregi, & Nieuwenhuijsen, 2002; Jauregi, Nieuwenhuijsen, & De Graaff, 2003).

The social relationships that come out of collaborative writing are usually developed through meaningful and objective work (Kessler, Bikowski, & Boggs, 2012; Storch, 2011). As a result, students learn from their peers’ strengths and weaknesses in writing as they collaborate and contribute with their knowledge and share experiences and strategies in the writing process while providing support in the difficult aspects of writing. Student interaction and peer learning in collaborative writing translates into students’ making their comments and ideas explicit while valuing their peers’ contributions to the group rather than focusing on individual achievement, all of which promotes a social way of thinking that may promote joint reflection (Mercer & Littleton, 2007). In addition, the social interaction that happens during collaborative writing contributes to students’ getting to know one another and learning from their peers in a natural way and in a safe social environment (Elola & Oskoz, 2010). Regarding content knowledge development, the interaction that occurs during the process helps students better understand the topics to be developed since the feedback they receive from different members of the group helps them reconstruct their previous knowledge, allowing new knowledge to emerge (Donato, 1994; Ede & Lunsford, 1990). Overall, student interaction and peer learning during collaborative writing help learners produce better quality texts and reduce the number of possible linguistic errors, thus leading to an increase in language development (Fernández Dobao & Blum, 2013).

Collaborative writing has positive characteristics associated with language teaching and learning. For example, it involves affective benefits for individuals and the group because it reduces anxiety, increases motivation, and improves interaction, self-confidence, and self-esteem (Johnson & Johnson 1999). Another benefit is the creation of a relaxed work environment in the classroom owing to the characteristic communicative exchange that takes place in collaborative activities (Reid & Powers, 1993). Additionally, the genuine audience conformed by peers provides learners with the opportunity to know what readers do and do not understand in their manuscripts (Rollinson, 2005).

On another note, previous studies have examined the practical uses of collaborative writing. They have found that it helps to improve individual writing and provides a natural context for delivering feedback and promoting an even more recursive writing process than individual writing practices (Dale 1994, 1997; Morgan, Allen, Moore, Atkinson, & Snow, 1987). These aspects encourage independence on the part of the writer and allow students to take responsibility for their learning. Bearing in mind the positive effects of collaboration, peers can become more effective than teachers in the writing process since as peers they share similar language and perspectives.

Collaborative writing

Ample evidence has been gathered on the topics of both L1 and L2 writing that favor collaboration for improving writing quality (Storch, 2005). Not only have gains in quality been reported but also in terms of awareness of the audience (Leki, 1993), learner motivation (Kowal & Swain, 1994; Swain & Lapkin, 1998), and heightened attention to speech structures and grammar and vocabulary use (Swain & Lapkin, 1998). Helping students become aware of their audience has an important advantage - it is peers who make up a student’s first audience, and it is they who can provide immediate feedback, thus ensuring an optimal collaborative writing experience can actually take place (Elola & Oskoz, 2010). In this collaborative context, responsibilities are distributed among the members of the group, which allows them to discover the benefits of helping one another at different stages of the process, whether a group member is not clear about an idea to write about or a conflict occurs and they must have a discussion to reach an agreement. Collaboration also helps learners to see writing as a process of learning and discovery (Hunzer, 2012; Storch, 2005). Thus, as the text is elaborated, a process of peer feedback construction also occurs, helping students to develop more analytical and critical thinking (Daiute, 1986; Storch, 2002). Furthermore, writing collaboratively and working together allows novice writers to practice constructive communication styles. This, in turn, results in texts with greater coherence and cohesion, more creative ideas and a wider linguistic repertoire than texts written individually (Fernández, 2009; Fisher, Myhill, Jones, & Larkin, 2010; Littleton, Miell, & Faulkner, 2004; Rojas-Drummond, Albarrán, & Littleton, 2008). Research has also shown that, when people write by working in groups, they produce more accurate texts than those working in pairs or individually as a result of sharing knowledge and experience (Fernández Dobao, 2012; Storch & Wigglesworth, 2007).

Technology in L2 Writing

Media evolution and the advent of Web 2.0, with websites, wikis, and blogs that highlight user-generated content, interaction, and collaboration (Ubilla et al., 2017), have had a tremendous impact on the way people interact and collaborate with one another (Lomicka & Lord, 2009). Technology now allows users to be creators and co-creators of content in virtual communities rather than solely recipients. In other words, as a set of technologies for social creation of knowledge, Web 2.0 brings together technology, knowledge, and users for the collective creation of content, the establishment of shared resources, and collaborative quality control (Freire, 2007; Ribes, 2007).

Web 2.0 applications allow learners to interact synchronously and asynchronously with peers, teachers, or themselves in relation to their own work and that of others (Brown & Adler, 2008; Oishi, 2007; Tharp, 2010). Especially useful in collaborative writing in educational contexts are free file storage and synchronization services, in particular those encompassing an office suite allowing for collaborative file editing (Lozano, Valdés, Sánchez, & Esparza, 2011), which do not require installation of any software (Conner, 2008). File storage and synchronization services such as these facilitate individual work and enhance collaborative work because they make it possible for people to share documents, whether just to view them in word processing format, to collaborate in their construction, or to publish them on the web (Conner, 2008). They also let users save different versions of a document and keep a record of them, which allows learners to perform a review of their writing process and interact almost immediately with their peers or teacher to receive their opinions regarding the text in question. In sum, file storage and synchronization services allow for both synchronous and asynchronous collaboration, and students can work simultaneously or at their own pace on the same document from different geographical locations, which distinguishes it from other tools such as wikis (Conner, 2008; Oishi, 2007; Brown & Adler, 2008; Tharp, 2010; Lozano, Valdés, Sánchez & Esparza, 2011).

The new capabilities offered by Web 2.0 tools have turned them into a mediating element to enhance collaborative work in second language acquisition (sla) processes, particularly in the development of productive skills such as writing texts in English as an L2. Despite scant research to date using file storage and synchronization services for collaborative writing, available work is promising as there is evidence they facilitate synchronous communication and, consequently, collaboration by strengthening connections among participants (Lozano et al., 2011; Tharp, 2010; Brodahl, Hadjerrouit & Hansen, 2011). In addition, they allows learners to concentrate more intensively on the content of the subject, thus developing better collaborative products (Lozano et al., 2011; Tharp, 2010). In a recent study, Brodahl, Hadjerrouit, and Hansen (2011) assessed perceptions of senior-year education students (N=201) toward collaborative writing that used Google Drive and EtherPad. Both of these tools are open-source, web-based collaborative real-time editors that allow for simultaneous co-editing of a text, by showing all participants’ edits in real-time in a different color, accompanied by a chat box in the sidebar for meta communication. Students were given a collaborative writing assignment and asked to answer an online survey. The objective was to determine whether perceptions depended on such factors as gender, age, digital competence, interest in digital tools, educational environment, and choice of tool. Results indicated that factors such as digital competence and positive attitude toward these tools yielded better results. It was determined that 47% of students appreciated being able to comment and edit others’ contributions in collaborative writing. A final reason in favor of Web 2.0 tools as mediating elements to enhance collaborative writing derives from Harris’ (2007) advice that the selection of a collaborative writing tool should prioritize interdependence, individual responsibility for the task, interpersonal skills, productive interaction, and reflection on group processes. After all, tools should be selected based on the objectives and activities involved in the process, in this case, collaborative writing.

Method

The present research is a case study that utilized both quantitative and qualitative methods. The quantitative dimension was associated with the identification of Chilean pre-service EFL teachers’ perceptions regarding a collaborative writing intervention in English, their self-assessment of their performance during the process, and the correlation between the two. The qualitative dimension sought to recognize the participants’ perceptions of the intervention based on their oral discourse.

Participants

The participants were 33 senior-year pre-service EFL teachers in a university in southern Chile. The students’ full program lasts five years and includes a professional teaching practicum in the final year. The participants were enrolled in courses taught in English as an L2 at the B2 level of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). Individuals at this CEFR level are considered to be independent language users who can identify the main ideas of complex written or oral texts and demonstrate fluency when they speak or write (Council of Europe, 2002). All participants were informed of the purpose, methods, and means of the study, and they were asked to sign an informed consent form before commencing the experiment.

The treatment in this study was implemented in an English language course aiming at the development of the learners’ communicative competence. It involved a collaborative writing intervention in which individuals produced six argumentative essays about different topics, in which they had to agree or disagree with established prompts, within a blended learning environment. This included six face-to-face and six distance sessions. The regular writing instructor, who is a native-speaker of English and who did not participate as a researcher in this study, conducted the teaching. The researchers designed the instructional units and materials but did not participate in the teaching other than indirectly by holding regular conversations with the instructor. Blended learning was implemented by means of information and communication technology resources for writing. Specifically, Google Drive was used for the collaborative process, and a blog containing instructional materials and the tasks was used to guide the treatment. In the collaborative writing process, the research subjects worked in teams in which they were asked to play specific roles in turns, i. e., drafter, reviewer, and editor. Within this framework, producing the argumentative essays involved the process writing steps (brainstorming ideas, drafting, revision, edition, and publication) studied in the course as part of the instructional design. Direct instruction on all writing steps was done in the face-to-face meeting with the instructor, and students needed to perform extra practice on their own using a blog that was designed for this purpose. This knowledge was also put into practice and perfected during the collaborative writing process with their peers.

Data Collection

To identify the perceptions held by the Chilean pre-service EFL teachers regarding the study’s collaborative writing intervention in English as an L2, a Likert-scale survey in English was given to the participants after the implementation of the treatment. The research subjects read nine statements gauging their perceptions and selected the most suitable option from the following: 1) totally agree, 2) agree, 3) neither in agreement nor in disagreement, 4) disagree, and 5) strongly disagree. For the analysis of these data, each item’s total score was calculated by adding its specific values (Hernández, Fernández, & Baptista, 2010). The statements included in this instrument were created by the researchers after the fashion of other instruments elaborated by Brodahl, Hadjerrouit, and Hansen (2011), Chu, Kennedy, and Mak (2009), and Li, Chu, Ki, and Woo (2012).

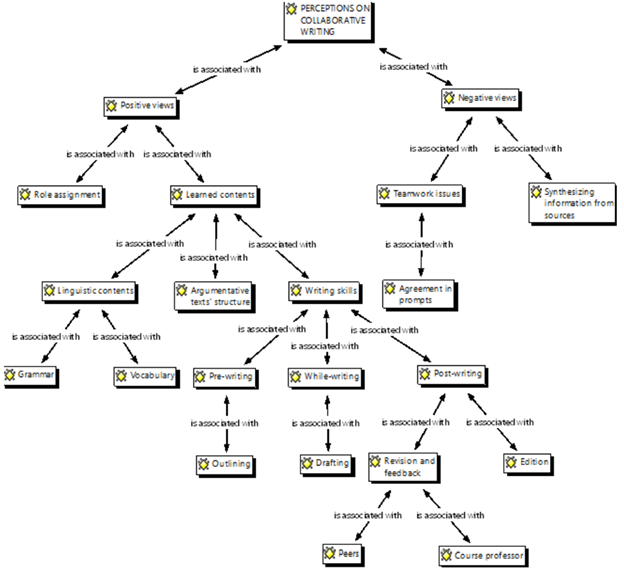

A semi-structured interview was also used to gauge participants’ perceptions regarding collaborative writing in English as an L2. Participants’ answers were recorded during the interview and then transcribed. Content analysis was utilized to process the qualitative data collected in the semi-structured interviews. For this, the transcribed responses were coded and categorized by means of Atlas.ti. Then, findings were plotted in a conceptual network (see Figure 1) generated by the software, showing all the semantic connections based on the participants’ oral discourse. This information was clustered into subcategories of positive views and negative views.

To obtain the pre-service EFL teachers’ self-assessment regarding their collaborative writing process in English as an L2, participants were asked to complete a rubric created by the researchers that allowed them to measure the degree to which they accomplished the collaborative writing tasks. According to Barberá and De Martín (2009), a rubric consists of specific assessment areas and their achievement levels. The dimensions considered in this instrument were: roles within the group, setting objectives, fulfilling objectives, quality of interaction, and task evaluation.

Finally, a correlation analysis using Spearman’s rho was run to measure the relationship between participants’ perceptions regarding collaborative writing and their self-assessment of the process. As all the data collection instruments in this study were created by the researchers, they were validated by three experts in the field. They were professors in an accredited doctoral program in linguistics at a traditional Chilean university, all of whom held a Ph. D. and a graduate degree in linguistics.

Results

The research findings were divided into the following categories, which are equivalent to the study’s research questions: 1) participants’ perceptions of collaborative writing in English, 2) participants’ self-assessment of their performance in English language collaborative writing activities, and 3) correlation between participants’ perceptions and self-assessment in the context of collaborative writing in English.

Perceptions of Collaborative Writing in English

Based on the study’s first research question, Table 1 summarizes the Chilean pre-service EFL teachers’ responses about perceptions of their collaborative writing process for argumentative texts in English. These data were generated by means of a Likert scale survey.

In order to obtain a more comprehensive view of the results, the nine dimensions in the survey were grouped into three categories corresponding to aspects of collaborative work described in the literature review: peer collaboration, goal setting, and role establishment (which further sub-divided into role assignment and role changes). Regarding peer collaboration, most participants (86.7%) agreed that they learned much from their peers’ suggestions during the collaborative writing process. In terms of goal setting, almost all (96.7%) agreed that having clear objectives from the beginning was beneficial for completing their work. As for role establishment, a high proportion (76.7%) agreed that it was a good strategy. However, it is noteworthy that a low proportion (36.7%) agreed with role changes during the process; that is, they preferred to maintain the assigned roles throughout the process rather than modifying the functions of group members.

Overall, quantitative results show that the pre-service EFL teachers held generally positive perceptions of how they approached the collaborative writing process. It seems they value cooperating with their peers and taking suggestions from them in order to learn. High proportions of the participants also demonstrated that they value setting goals from the beginning of the writing process, and that they value peer contribution in terms of editing and comments.

To illustrate the qualitative results on the pre-service EFL teachers’ perceptions of the collaborative writing intervention, a conceptual network can be seen in Figure 1. These data were generated by means of a semi-structured interview conducted in English. The participants’ responses were categorized into positive and negative views. The quotations selected in this paper are verbatim so they may contain minor errors in word selection or style, which we have kept intact.

According to Figure 1, participants held mostly positive views of collaborative writing. Their answers in the semi-structured interview revealed that the pre-service EFL teachers gave particular importance to role assignment as this aspect of collaborative writing facilitated a smooth writing process in the L2, evident in the following interview excerpt: “I liked the fact that all the team members performed a different responsibility when writing. Roles were assigned by taking each classmate’s strengths into account” (Participant 03). Role assignment also helped to overcome difficulties such as insecurity, as this participant mentioned: “In my case, I don’t like to write since I tend to make mistakes. I preferred to contribute by carrying out another activity. That is why I was in charge of looking for sources to cite in the essays” (Participant 16). Positive views also referred to the conceptual and procedural content that pre-service EFL teachers learned owing to suggestions made by peers and the instructor during the process. Responses focused on linguistic content, argumentative text structure, and writing skills.

When participants mentioned linguistic content, they often referred to it in terms of English grammar and vocabulary, as evidenced by the following: “When I wrote the texts, there were some grammar tenses I did not manage well. My classmates helped me to correct these in my production” (Participant 01). This view was shared by Participant 12, as seen below:

It was difficult for me to write certain grammar structures. When my classmate played the role of reviewer, she usually told me there were some verbs which should have included “-ing” instead of “to.” That helped me to improve when writing a text. (Participant 12)

As for vocabulary, pre-service EFL teachers also valued peer contribution for the purpose of improving in this area. For example, Participant 05 shared the following: “The collaborative methodology helped me to be aware of my mistakes when writing. Before, I tended to translate words from Spanish into English, but their meaning was wrong.” Another participant stated, “When I worked as a drafter, vocabulary in English was one of my weaknesses. My classmate helped me realize [sic] the words which were more suitable for the sentences included in the texts” (Participant 08).

Pre-service EFL teachers also valued gaining awareness of argumentative text structure, as seen in this response: “When I carried out university writing assignments before, I was not conscious of texts’ structures [sic]. I understand now that every type of text has a specific format. Prior to the intervention, I only wrote paragraphs” (Participant 01). Similarly, another research subject commented, “The project has helped me to learn the textual structure I must follow when writing. For example, I need to know where to include a thesis statement, the arguments, the paragraphs’ order” (Participant 30).

Regarding writing skills in English, positive views were expressed on their successful development owing to the instructional intervention. In this respect, the pre-service EFL teachers highlighted the three main steps they learned in the writing process: pre-writing, while-writing and post-writing.

Consistent with what students were taught in the face-to-face component of the blended experience, students reported that their pre-writing stage consisted of outlining before text production. Pre-service EFL teachers reported that this helped them to organize the ideas they planned to include in their written texts, as is evident in this excerpt: “Prior to the intervention, I only wrote texts in English without following steps. However, I nowadays [sic] know that I have to brainstorm and order my ideas so as to [sic] start producing” (Participant 28). Another participant developed more clarity as a result of outlining as a pre-writing step:

In writing tests I took before, I combined all my ideas as I thought of many. This made my production unclear. I understood, in the project, that outlining is useful to decide which idea would be included in each paragraph” (P01 [04:04]).

It is interesting to note that, pre-service EFL teachers in this study seem to have learned that the while-writing stage involves drafting that should be based on the outline they produced during the previous stage. This is clear in what one of the interviewees asserted: “I learned that I should start writing after I have organized my own ideas. In past writing activities, I only wrote without a determined order. This makes the writing process less confusing” (Participant 20). Conversely, another participant said: “Quality writing involves producing in a progressive manner. While drafting, we can add more details to the outline” (Participant 15). From these examples, we can conclude that learners view the while-writing stage as a dynamic process in which both the outline and the drafting feed on and contribute to each other.

Regarding the post-writing stage, pre-service EFL teachers valued the revision and feedback provided by peers, in which they reviewed and edited their production, because it helped them to identify their weaknesses in writing, as explained by one participant: “When I wrote, I could not notice my mistakes [sic]. So, it is useful to have another person reading your manuscript. In my case, my classmates have pointed [sic] out what was unclear in my texts. Then, I have made changes [sic]” (Participant 10). Another participant emphasized the importance of suspending judgement: “The purpose of reviewing and correcting our classmates’ production was not to criticize. It was to benefit all of us when rewriting” (Participant 18). This example shows that suspending judgement was important in the post-writing stage as it encouraged negotiation of meaning and self-correction rather than pointing out at mistakes.

Moreover, pre-service EFL teachers found that revision and feedback provided by the course professor concerning their written texts was positive, and they perceived these practices as beneficial components for the edition process, as expressed in the following excerpt: “We thought we were writing well before the submission. However, the professors suggested we should [sic] correct the text’s structure [sic]. We were not used to receiving feedback on our writing production, so this was useful to enhance our production” (Participant 17). Along the same line, another participant commented: “I improved the way I wrote in English by considering the observations provided by the module professors. Their comments were not focused on the same writing criteria. One reviewed the grammar and the other assessed the way the text was written” (Participant 14).

On the other hand, participants’ negative views included teamwork issues they experienced as they carried out the writing assignments. One example is this interview excerpt: “I did not learn how to work with my classmates in my university training. In my group, my classmates were very rigorous. The way they worked was not suitable [sic] with mine” (Participant 12). Another participant added that “teamwork has not been successful enough, in my case. My classmates have not contributed too much in the writing process” (Participant 29).

An important teamwork issue was the participants’ difficulty reaching agreement over the writing prompts, owing to different perspectives on the topics associated with them. Despite this, pre-service EFL teachers indicated they managed to achieve conflict resolution, which is evident in this excerpt: “When we wrote a text about abortion legalization, two of us had a positive view on the prompt. However, one classmate disagreed, so we decided to include only one position in the written production” (Participant 02). Another subject referred to a similar situation: “One day we had to decide if we agreed or disagreed with the task’s prompt. We all had contrary positions, but we all decided we would be against the essay prompt” (Participant 33).

Another source for negative views on collaborative writing stemmed from the participants’ difficulty in synthesizing information from sources prior to essay production, as mentioned by one pre-service teacher: “At the beginning of the semester, we included too much information in the texts. We were not able to summarize the sources’ most essential ideas as everything was important to us. Summarizing is still difficult for me” (Participant 12). In the same vein, another participant provided a suggestion for a future writing intervention: “We should be allowed to take more advantage of the sources. The texts we wrote were very synthesized because we had to delete so many interesting ideas” (Participant 11).

Self-Assessment of Performance in English Language Collaborative Writing Activities

In the context of the study’s second research question, Table 2 summarizes the participants’ responses regarding the self-assessment of their performance in the production of argumentative essays during the intervention.

Participants were asked to self-assess collaborative work according to the following categories: roles within the group, setting objectives, achieving objectives, quality of interaction and evaluation of the task. Results indicated that all aspects fell within a range between acceptable and outstanding, with over 90%. The ones that got the highest scores were setting objectives and task evaluation. A logical pedagogical implication is to request explicitly, prior to actual writing, that students set clear objectives for writing before starting to write, and self-assess their writing process once they finish writing.

Correlation Between Perceptions and Self-Assessment in the Context of Collaborative Writing in English

Table 3 summarizes responses to the third research question, which measured the relationship between the pre-service EFL teachers’ perceptions of collaborative writing and their self-assessment of their performance in the intervention.

A Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient was run to determine the relationship between the participants’ perceptions of collaborative writing in English and the self-assessment associated with their performance in the intervention. The results indicate that there was a weak, positive correlation between these variables that was statistically significant (Rs(33) = 0.36, p = 0.05), which means that the pre-service EFL teachers’ positive perceptions of the collaborative writing process are associated with high self-appraisal scores in terms of their performance in the intervention.

Discussion

Both quantitative and qualitative results in this study suggest that the participating pre-service EFL teachers held positive perceptions toward collaborative writing in a foreign language. This fact corroborates the findings of similar studies (see, for example, Ewald, 2005; McDonough & Sunitham, 2009; Storch, 2005; Zeng & Takatsuka, 2009). Learner responses in this research project indicated that most of them supported collaborative writing and found it useful in many aspects. This coincides with Shehadeh’s (2011) study, in which students stated that, although the collaborative writing experience was new to them, it helped them to improve their writing skills and oral production in terms of fluency. Additionally, the pre-service EFL teachers in the present study stated that they learned much from their peers’ suggestions during the collaborative writing process, and it helped them to generate ideas, discuss and plan, generate the text collaboratively, obtain immediate feedback, and refine the text more effectively.

The participants also pointed out that working collaboratively helped them to integrate conceptual and procedural content owing to the suggestions made by their peers in the productive process, which focused mainly on grammar, vocabulary, and the structure of an argumentative text. These findings coincide with other studies in which most research subjects recognized the positive impact of collaborative writing in allowing them to improve aspects of content, organization, and linguistic accuracy in their manuscripts (Fernández Dobao, 2012; Fernández Dobao & Blum, 2013; Sun & Chang, 2012). Integrating conceptual and procedural content while working with peers in collaborative writing has also been found in previous research to improve the quality of students’ texts, more specifically, their content and structure, especially when using technological tools (Elola & Oskoz, 2010). Moreover, in agreement with the present study, previous research has indicated that participants show positive attitudes regarding the work they develop in groups or pairs. In fact, they state that sharing their ideas and knowledge helps them to develop creativity and to be more precise in the use of the language (Kim, 2008; Shehadeh, 2011; Storch, 2005; Storch & Wigglesworth, 2007; Swain & Lapkin, 1998). Sharing ideas and knowledge in peer work offers learners the opportunity to collaborate in solving their language development problems and co-construct new grammatical and lexical knowledge.

Considering quantitative data, the pre-service EFL teachers also placed importance on setting goals as part of the collaborative writing process, given that almost all participants agreed that having clear objectives from the beginning was appropriate for the work to be completed. These results are supported by those of Vallance, Towndrow & Wiz (2010), who argued that language learners must be engaged in a mutually beneficial relationship in order to achieve predefined goals and make the collaborative process successful.

Finally, when the participants were consulted about the establishment of roles (including assignments and changes), most of them agreed that role assignment was a good strategy. Quantitative data are supported by the qualitative information obtained in the semi-structured interviews, which showed that most learners valued role assignment, despite its challenges, as it facilitated the development of writing skills in English. This is reflected in previous research, which has found that teams in which roles are assigned tend to work more efficiently and productively, hassle-free, and with improved task development and levels of satisfaction (Cohen, 1994; Zigurs & Kozar, 1994). Moreover, role assignment can minimize certain problems, namely, non-participation and attempts by a single group member to dominate group interactions (Cohen, 1994; Strijbos & De Laat, 2010). In sum, assigning roles in collaborative tasks helps to determine the quality of knowledge construction produced in a learning community (Aviv, Erlich, Ravid, & Geva, 2003).

Notwithstanding, when it came to changing roles, it is interesting that most students in this study were uncomfortable with the strategy, offering a contrasting point with prior studies in which students said that it was more effective to change peers every two or three sessions (Aviv, Erlich, Ravid, & Geva, 2003), as it allowed them to create a more engaging learning atmosphere in the classroom. A possible reason for this is idiosyncratic differences. It is also possible that students would prefer to stay in their roles longer to gain more confidence in the task before moving on to a new one.

A plausible explanation for the positive results in these participants’ perception of collaborative writing may be that they saw teamwork as an expected outcome because it is one of the cross-curricular competences explicitly embraced by the university where the study was conducted. In fact, the students at this university are expected to identify in themselves and their teammates the strengths and weaknesses that will enable them to carry out a task successfully. Additionally, the university expects students to participate actively in teamwork to foster confidence and contribute to the development and successful completion of the tasks entrusted to them through effective work in professional contexts. Here, teamwork implies that individuals develop not only sympathy and empathy but also a deep commitment to the interests and processes of their team, generating strong affective bonds. At the same time, the bond with their membership group is expected to be effective, to the extent that individuals interact, participate, and endorse the purposes and objectives of their team.

Limitations and Further Research

Despite the positive results of this study, it is important to bear in mind that launching any collaborative writing effort is time consuming and requires detailed planning of a number of aspects, such as learning objectives, the tasks and roles assigned to the learners, as well as instructional material and design. The extent of student familiarity with collaborative learning tools and methods can also have an effect on the quality of text production. In fact, collaborative writing via Web 2.0 tools requires managing at least three dimensions simultaneously: (a) content, organization, and linguistic accuracy, (b) conflict, peer participation and motivation, and (c) access and effective use of technology.

One aspect that is particularly difficult to control in collaborative work is human relations. In this study, we opted for the strategy of self-selection of team members because, as several studies have made clear, it provides benefits such as improved academic results and higher quality work (Van der Laan Smith & Spindle, 2007; Hilton & Phillips, 2010; Graham & Misanchuk, 2004). With self-selection, students tend to have fewer difficulties in organizing their schedules because they know one another, and this allows for more conducive work and more willingness to begin work immediately (Graham & Misanchuk, 2004; Hilton & Phillips, 2010; Van der Laan Smith & Spindle, 2007). In spite of this, some groups had difficulty organizing themselves to accomplish the instructional tasks presented in the blog and to decide who would perform the expected roles (e.g. drafter). Nevertheless, they managed to overcome this difficulty and carried out the requested tasks well. In sum, human relations are an essential factor to consider in a study of this kind. Bearing the principles of Engeström’s (1987, 2001) activity theory in mind, it is not enough to consider activities and how learners will perform them in instructional processes; it is important for teachers to plan beforehand the way learners will work with diverse peers to meet a common goal.

Another aspect to consider is the likelihood that someone might prefer to work on his or her own. In this study, participants did not express any problem with the idea of working in teams. However, it is wise to plan for specific adaptations in case someone does not wish to work collaboratively. Forcing a methodology of work can end up being detrimental to the student, the class, and the final work. In such cases, it is advisable for the teacher to respect learners’ preferences while at the same time highlighting the benefits of collaborative writing because, more than ever today, collaborative work is fundamental in all kinds of social and professional activities.

Finally, although the findings derived from this study can be of interest to the ELT educational community and programs aiming at developing learner-centred perspectives for writing, implications of these results should be handled with care, as they are not meant to be generalizable to the broader community. Still, results may be valuable to those interested in new dynamics to address pedagogies in the contemporary language classroom in a variety of educational contexts, but particularly for more advanced students of English as an L2. Nevertheless, it is important to consider what adaptations may be necessary for students of other languages, those immersed in other cultures or different educational systems, those in deprived contexts where access to technology may be an issue, and those whose level of English may not meet the proposed standards for their country. All this warrants further study.

Conclusions

Evidence provided in this research indicates that collaborative writing in English as an L2 using Web 2.0 technology is not only possible and effective but also desirable for a number of reasons.

Firstly, learners positively value the experience of writing texts collaboratively because it allows them to expand their experience beyond what they would be able to do autonomously. For example, they consider other points of view regarding a topic; interact and negotiate meaning around a given position; and become aware of aspects of quality, content, organization, and linguistic accuracy in the co-authored texts that may go otherwise unnoticed. Moreover, sharing ideas and knowledge helps learners to develop creativity, self-reflection, critical thinking, a positive attitude, and an open mind about what others have to say. In sum, learners appreciate the opportunity to discuss and reflect upon group ideas regarding a topic and texts of their authorship because they see it clearly as an opportunity for skill development as a process of interaction and negotiation of meaning in L2 acquisition.

Secondly, blended collaborative writing fosters communicative competence in the L2 beyond writing skills alone because students search for information on the web, watch videos, and engage in discussions to decide what and how to write. Communicating with other members of the group as they work with the written and oral material in co-authoring argumentative texts requires learners to engage in meaningful interactions as they receive and provide feedback on task completion. This in itself is an incentive to persevere in a process that takes much time, effort, and discipline, characteristics that may otherwise make it demotivating for learners.

Thirdly, as writing is a key challenge in SLA, learners highly value the opportunity to develop their skills in a more relaxed environment and in a communicative context where there is regular peer feedback on their performance, which may not be possible in face-to-face-only classroom settings due to time and space constraints. In addition, sharing knowledge with a real audience -in this case, their peers-, fosters higher quality responses from participants because they are more willing to undergo revisions and editing from peers to improve final draft quality. This may have cultural underpinnings, as students in this context tend to see the instructor more as a judge, error corrector, evaluator and assignment grader (the sage on the stage) than a facilitator and collaborator (the guide on the side). The sense of belonging they get from the co-authorship process is clearly an advantage. In this respect, promoting peer-feedback and providing sufficient time and opportunity for it are key in instructional design, as peer suggestions throughout the collaborative writing process encourage idea generation, discussion, planning, reviewing, reformulating, editing, and proofreading, which may be neglected in solo writing.

Finally, in terms of teamwork, learners believe it is essential to have established and clear objectives, role assignment, and role rotation from the very beginning as part of the collaborative writing process. This pushes them to engage in a mutually beneficial relationship to achieve common goals, thus allowing for more efficient, productive, and hassle-free work. Moreover, doing so helps to improve task development and satisfaction levels and minimize the likelihood of non-participation or a single group member attempting to dominate group interactions. A caveat is in order here, though, as evidence shows that learners may prefer to keep the first roles they were assigned for the whole process or at least until they feel comfortable enough to assume a new role.

Overall, this study is a contribution in the field as it sheds new light on factors that may facilitate the role of Web 2.0 technology in collaborative writing for L2 learning. Its analysis of learner responses reveals that a blended learning design for collaborative writing can foster an effective EFL/ESL learning environment and render positive learner perceptions. In this respect, instructional decisions are key in ensuring successful implementation of a blended learning experience. Further studies may focus on enhancing writer identity, training learners for optimal peer feedback, participatory patterns in the co-authorship process, and mediating factors such as task type, personal goals, and self-efficacy, among others.

The prevalence and worldwide adoption of Web 2.0 technologies, even in tertiary education institutions, also warrants further research on the development of other linguistic skills and strategy use. A final avenue for future research is telecollaboration, as it would be interesting to see how interaction among EFL/ESL learners and native speakers who are geographically distant from one another may pose new challenges and opportunities in an already complex and exciting scenario.