INTRODUCTION

Electrical networks transport electrical energy from generation points to consumption points. Therefore, their design must guarantee the quality conditions for the operation of the electrical system and loads. These conditions are generally voltage regulation, energy losses, chargeability, power balance, and harmonic distortion (Deboever et al., 2018; Haque & Wolfs, 2016).

An electrical network design guarantees the operation within a functional and regulatory range under normal and non-normal operation conditions. The latter may include equipment or line disconnections, atmospheric discharges, or short circuit failures (Bajaj et al., 2020). Additionally, severe weather conditions, malicious damage caused by humans, natural disasters, non-linear loads, equipment maneuvers, and equipment in poor condition produce non-normal operating conditions.

Likewise, distributed generation (DG) systems could modify the operation of the network, which sometimes leads to violations of the operating conditions (Bajaj et al., 2020; Cadini et al., 2017; Correa-Flórez et al., 2016). However, the impact on the electrical network due to variations in operating conditions, unexpected events, and permanent modifications could be characterized by evaluating system resilience (Borghei & Ghassemi, 2021; Mousavizadeh et al., 2020).

There is no proper or unified concept to define resilience applied to low voltage (LV) electrical networks. Nevertheless, the resilience of an electrical system is conceived to a greater extent as the capacity of the network to withstand an adverse event without losing operating conditions, reducing the impact on the service quality to users, recovering after the event, and adapting to new operating conditions (Borghei & Ghassemi, 2021).

The concept of resilience in electrical systems emerged in the last decade (Cadini et al., 2017; Mousavizadeh et al., 2020), and lots of research are oriented to quantification in different scenarios. Resilience can be measured based on reliability, robustness, adaptability, and recoverability indices (Rocchetta et al., 2018). All cases evaluate the level of impact of an adverse event on the electrical network.

In addition, the integration of photovoltaic (PV) systems in residential and commercial LV networks has increased in the last decade (Aleem et al., 2020; Gandhi et al., 2020). Thus, there is a need to carry out studies focused, for instance, on the performance of the networks in the face of variations of the injected power due to fluctuations in solar irradiance and the characterization of the resilience of LV networks (Brinkel et al., 2020). This could favor the networks’ capacity to withstand adverse conditions. Moreover, it will allow operators to establish complementary operating conditions of existing networks and define strategic plans to respond to PV integration in the medium and long term.

This paper is organized as follows: the concept sections present a review of the PV systems’ significant impacts in LV and describe the concept of resilience in electrical networks along with the typical scenarios for evaluation. Then, the discussion section proposes how the concept of resilience could be applied to evaluate the performance of LV networks that integrate PV. The results section presents a case study to apply the discussion, and the final section presents the conclusions of this research.

IMPACTS OF THE INTEGRATION OF PV SYSTEMS ON LV DISTRIBUTION NETWORKS

The impacts of the integration of PVs in LV networks depend on the network architecture, the PV penetration, and the meteorological conditions (Haque & Wolfs, 2016). According to the architecture, the impacts are related to the impedances of the lines, the voltage regulation equipment, the protections, and the system’s response times.

Typically, an increase in PV penetration implies an increase in impact levels. As for the meteorological conditions, the impacts of the PV system depend on the average, maximum, and minimum values of solar irradiation and ambient temperature, as well as on sporadic variations (Deboever et al., 2018; Giral-Ramírez et al., 2017).

Moreover, PV systems could favor the electrical network’s reliability, load availability, and voltage regulation; relieve power congestion; and reduce losses and operation and billing costs. For example, Shanshan et al. (2018) study the implementation of DG as a strategy to mitigate disconnection events.

However, PVs could also alter the voltage waveform, produce voltage and power unbalances, generate reverse power flows, and cause premature deterioration in regulation, control, and protection equipment (Shanshan et al., 2018). Some significant impacts of PV systems on distribution networks are described below.

Impacts on the voltage profile

PV systems in LV could help keep the service voltage within acceptable limits (Aleem et al., 2020). This is possible because the strategic location of the PV systems reduces currents in certain sections of the network, which improves voltage regulation and reduces losses (Montoya et al., 2020). However, the unplanned and massive integration of PVs could cause overvoltage or low voltage (Deboever et al., 2018; Haque & Wolfs, 2016).

Depending on the sitting of the PV system, a higher PV penetration can be achieved without violating the voltage limits. For example, some simulations have shown that a strategic sitting can achieve a penetration of 50% of the feeder without violating the limits of voltage regulation (Tedoldi et al., 2017).

Impacts on power and voltage balance

Non-linear power inverters could lead to injecting distorted currents and unevenly delivering power to the phases of the system (Borghei & Ghassemi, 2021). In addition, distribution networks typically operate with unbalanced voltages, which is a product of unbalanced load in the commercial and residential sectors. Thus, an unbalanced power injection of PV systems could lead to an unbalance in the service voltage (Emmanuel & Rayudu, 2017).

Impacts on the coordination of protections

In LV networks, the protection farthest from the supply bus must act first to isolate the section affected by a failure. The other protections act in sequence as a backup if the primary one does not do it.

Based on Ates et al. (2016) and Paliwal et al. (2014), this can indicate that the conventional LV protection schemes are vulnerable to PV integration. Moreover, three main technical aspects could cause malfunctions in the coordination of protections:

The PV systems integration could cause bidirectional power flows in the network, which means that the coordination of protections based on a unidirectional way is ineffective.

The network could present high variations in the current magnitude when connection and disconnection events occur or the power injected by the PV varies.

The short-circuit current tends to increase with PV integration

RESILIENCE IN ELECTRICAL NETWORKS

Electrical network resilience could be defined as the ability to withstand an adverse event without losing operating conditions and recover after the event (Afgan, 2010; Borghei & Ghassemi, 2021). A resilient electrical network simultaneously evaluates the behavior of the systems that face an event and the consequences (Baroudand Barker, 2018).

The behavior of the network can be represented by a parameter, Φ(𝑡) , generally called sustainability (Afgan, 2010). The probability that the network will operate in its normal mode is called reliability. When a disturbance, e(𝑡), occurs, Φ(𝑡) decays according to the vulnerability to e(𝑡). The network’s ability to withstand perturbations, e(𝑡), is called robustness (Baroud & Barker, 2018).

Once e(𝑡) has finished, the network experiences a transient state until it seeks a stable one. After a time, t r , restoration starts until a stable normal operating mode, Φ(𝑡r), is reached. The final operation state, Φ(𝑡f), could be different from the initial Φ(𝑡0). This depends on the disturbance level and recovery of the network. The network’s capacity to reach normal operating conditions is called recoverability (Baroud & Barker, 2018).

The literature shows mostly studies on the resilience of electrical networks to extreme weather events. However, these have a low probability of occurrence and high impacts (Haixiang et al., 2017; Ouyang & Dueñas-Osorio, 2014), compared to events directly or indirectly caused by humans (Liu et al., 2017; Shanshan et al., 2018).

There are few studies related to the resilience of electrical networks to permanent modifications, such as Deboever et al. (2018) and Blaabjerg et al. (2017). These modifications have a low impact but could cause a sudden change of network components and strengthen or weaken the response to a temporary disturbance. They could integrate new elements as generation sources, voltage regulation equipment, or distribution lines, and they could also imply modifications of distribution transformers, the connection point of a load, or an increase in the nominal power of a generation source. Table 1 summarizes the analysis scenarios and the resilience evaluation indicators for the distribution networks according to the literature.

Table 1 Studies on the evaluation of resilience in electrical networks

| Scenario | Indicator | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Several weather conditions | Generation cost (Shang, 2017) | It uses a dynamic isolated microgrid for supply during power outages |

| Vulnerability, redundancy, and adaptability (Espinoza et al., 2016) | It evaluates the adaptation of power systems to frequent natural disasters | |

| Hurricanes | Risk probability and robustness (Ouyang & Dueñas-Osorio, 2014) | It analyzes power systems with high probability of hurricanes |

| Natural disasters and human attacks | Supply capacity and restoration time (Bie et al., 2017) | It analyzes the infrastructure of power systems and the measures taken around the world |

| Reliability, island mode (Haixiang et al., 2017; Rahimi & Davoudi, 2018) | They analyze the capacity of DG sources such as electric vehicles and microgrids to improve the resilience of a residential electrical network | |

| Natural disasters in cascade | Reliability and supply capacity (Cadini et al., 2017) | It analyzes the capacity of a transmission network to maintain service in case of climatic disasters |

| Extreme weather events | Operation cost and power supply capacity (Chong et al., 2017) | It proposes an operation strategy to improve the resilience of power systems |

Source: Authors

DISCUSSION

This section integrates the bibliographic review. It proposes preliminary guidelines for evaluating the performance of an LV network through resilience. It considers PV power injection as a disturbance facing the electrical network.

There is currently little research on the resilience of electrical networks before DG integration. However, some studies are related to the use of smart grids and microgrids as a strategy to improve the response of networks to extreme events (Liu et al., 2017; Shanshan et al., 2018).

Likewise, the integration of complementary components such as hybrid electric vehicles as generation and storage systems could supply the critical loads during a natural disaster or power outages (Rahimi & Davoudi, 2018; Shanshan et al., 2018).

On the other hand, it is usual to evaluate the maximum DG power that could be installed at a node in the network without compromising the operating conditions. Generally, the IEEE 1547 standard (2020) is taken as a reference for operating conditions. The maximum power capacity is called Hosting Capacity (Shivashankar et al., 2016). It is a way to assess the electrical network’s resilience, and it ensures that the networks do not lose operating conditions due to the integration of the DG.

Although the consulted literature does not consider evaluating LV networks’ resilience directly, it is possible to approach it from indexes that relate the impacts of a disturbance or modification in the network with its response. The evaluation indices are obtained from the normalization of the operating parameters affected before the disturbances and evaluation scenarios, particularly in the face of climatic and operational disturbances.

Each resilience evaluation index must be related to an operation parameter. The operating parameters are those established by the IEEE 1547 standard (2020) for DG interconnection and others determined from the review of related literature. The evolution over time of each evaluation index in the face of a disturbance is called sustainability (Afgan, 2010).

The resilience of each operation parameter can be determined from the integration of sustainability, and the total resilience of the network from a weighted parameter sum.

PV integration could be considered favorable if the evaluation indexes are kept close to 100% and are higher than in a reference scenario, which could be the same network without PV generation or a network at a standardized level for this test.

The electrical network’s operation can be quantified through a sustainability function, Φi(𝑡), by an evaluation index. Before a regular operation of the system, the index must remain constant and close to 100%. A disturbance, e(𝑡), can produce a variation and a transitory state of Φi(𝑡).

It is possible to quantify the resilience of each parameter (Ri) from this variation and the transitory state, which would be the area between ideal sustainability (Φi(𝑡) =1) and its evolution before the disturbance. This strategy simultaneously evaluates the definitions of robustness, adaptability, and recoverability, and it includes operation variations and response times. Figure 1 represents the evolution of a resilience evaluation index in the face of a disturbance.

The assessment of the resilience evaluation indexes can be studied in typical scenarios of distribution system disruption with PV systems. In addition, the evaluations can be made from simulations of the behavior of the PV system and the characteristics of the electrical network.

The evaluation scenarios must include system-specific disturbances such as voltage gaps, voltage peaks, frequency variations, and voltage unbalances. They must also consider external disturbances such as climatic variations (solar irradiation and temperature) and faults (disconnections and short circuits).

CASE STUDY

A case study is examined to apply what was exposed in the discussion section. An evaluation of the voltage regulation index is applied to estimate a resilience index at the point of common coupling (PCC). The setting of this case study is Universidad Industrial de Santander.

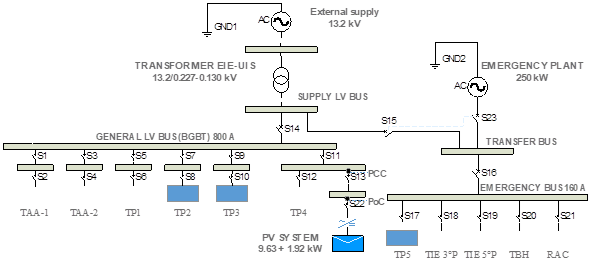

The electrical network of the building is appropriate for this study since it has smart meters in the primary nodes of the network. It also has an interconnected PV system through microinverters (one for each panel). Figure 2 presents the electrical connection diagram of the Electrical Engineering Building (EEB). More detailed information of the EEB can be consulted in the research by Parrado-Duque (2020) and Téllez-Santamaría (2020).

The considerations of the case study are presented below:

Source: Authors

Figure 2 Electrical connection diagram of EEB, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Colombia

Electrical network model

For the sake of simplicity, the electrical network is modeled as a single-phase equivalent. Loads are modeled as constant power, and wire conductors are modeled as constant impedance. The power output delivered by the PV system is calculated according to MPPT and the irradiance and temperature. Figure 3 presents the diagram of the single-phase equivalent Simulink model of the EEB’s network.

Power profiles for test

The test uses actual electrical measurements from the EEB. The electrical variables used are the voltage in the primary supply bar and the active and reactive power in the bars of each floor. The PV system uses the temperature and solar irradiance information obtained from the weather station installed on the terrace of the building.

A period with disconnection events due to high PV generation while a low load is selected for the test. The sampling period is one month (from October 17th to November 16th, 2019), with a time step of ten minutes. The maximum power generated by the PV system is calculated using Equations (1) and (2).

where 𝑃𝑃𝑉,𝑛 is the PV system peak power [kWp], 𝐺𝑎,0 is the standard condition irradiance [W/m2], 𝐺𝑎(𝑡) is the current solar irradiance in [W/m2], 𝑇𝑎(𝑡) is the current ambient temperature in °C, 𝜂𝑖𝑛𝑣 is the inverter efficiency 𝑃𝑃𝑉(𝑡) is the PV system active power at 𝑡 [kW], 𝑓𝑝 is the operating power factor, and 𝑄𝑃𝑉(𝑡) is the PV system reactive power at 𝑡 [kvars].

Evaluation of the voltage regulation index

Equation (3) is proposed to evaluate the voltage regulation index every day. Finally, the results are averaged for the test period. The parameters of (3) are tuned according to the case study (Parrado-Duque et al. (2019) expand this discussion). Figure 4 presents the transformation graphically.

Here, 𝑉%𝑅𝐿 and 𝑉%𝑅𝐻 are the voltage regulation limits; 𝑉%𝑅𝑚𝑖𝑛 and 𝑉%𝑅𝑚𝑎𝑥 are the voltage regulation limits allowed for the electrical network; 𝑚𝐿 and 𝑚𝐻 are the slopes, which are determined according to the regulation limits; and 𝑏𝐿 and 𝑏𝐻 are the corresponding cut points. In the case study, an acceptable voltage value between 0,97 p.u. and 1,03 p.u. is Φ%R=1, and an unacceptable voltage of less than 0,8 p.u. and greater than 1,1 p.u. corresponds to Φ%R=0.

PV power curtailment

According to Tonkoski et al. (2012), curtailment is applied to the power PV generated to reduce the overvoltage in the PCC produced by the injection of PV power. The curtailment strategy is given by Equation (4).

Here, PPV(𝑡) is the maximum power that the PV system can deliver at time t, and it is given by Equation (4); and 𝜂𝐶𝑢𝑡 is the curtailment index that varies between 0 and 1. It is obtained from the PCC voltage. In the case there is no overvoltage in the PCC 𝜂𝐶𝑢𝑡 =1, if there is overvoltage, 𝜂𝐶𝑢𝑡 decreases until a proper voltage regulation is reached or until 𝜂𝐶𝑢𝑡=0.

Results and analysis

The results were obtained in MATLAB through a quasi-static power flow in Simulink. The voltage regulation index was evaluated without the curtailment strategy and then by applying it.

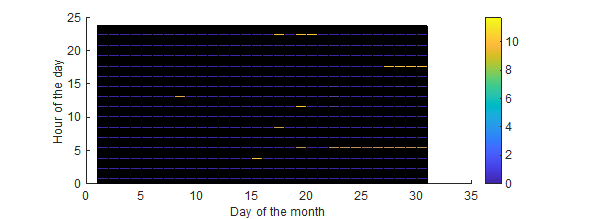

Figures 5 and 6 present the voltage profile for a day without the curtailment strategy and the voltage regulation index using the transformation described in Figure 4. The voltage regulation index was evaluated for each time step.

Figures 7 and 8 present the voltage for the network at a given time during the month and when applying the curtailment strategy. Note that it considers the working hours between 6:00 and 20:00. Finally, Table 2 presents the summary of the results obtained.

Source: Authors

Figure 8 Voltage regulation in the PV system’s PCC while applying the curtailment strategy

Table 2 Studies on the evaluation of resilience in electrical networks

| Parameter | Non- curtailment | Curtailment |

|---|---|---|

| Voltage regulation index | 0,84 | 0,845 |

| Overvoltage total hours | 59,8 h | 42,0 h |

| Overvoltage working hours | 31,0 h | 15,8 h |

| PV generation | 1,6 MWh | 1,6 MWh |

Source: Authors

This case considers overvoltage if the voltage regulation in the PCC is equal to or greater than 10%. Note that the voltage regulation index, 𝛷%𝑅, indicates potential regulation problems, which is consistent with the total overvoltage hours that the PV system presents.

When applying the curtailment strategy, it is possible to slightly increase 𝛷%𝑅. However, a significant decrease is achieved in the total hours with overvoltage, especially in the working hours (it is reduced by 49%). Therefore, the curtailment strategy does not affect the energy delivered by the PV system.

According to the results, applying curtailment strategies to the PV system can improve the level of resilience of the electrical network of the EEB. It is also noticed that the voltage regulation problems are typical of the network and not of the PV system. Therefore, there is an opportunity to improve applied voltage regulation strategies on the supply bar or feeder.

CONCLUSIONS

The resilience of an LV network with PV integration before disturbances has not been evaluated directly in the consulted literature. However, this can be approached from the perspective of the variation of the response in the networks to the impacts and effects that PV systems produce in the face of climatic variations and operation disturbances.

A correct evaluation of resilience must quantitatively define the normalized resilience indices from the operating parameters of the network affected by the PV integration. Parameters have been identified according to the literature and experience in the dissing of distribution networks.

It is recommended to use real operating profiles of the PV system and the network in order to obtain low error results. The case study shows congruence between the value found in the voltage regulation index and the overvoltage in the network. It also shows that the application of power management strategies can improve an electrical network’s resilience level.