Introduction

As of December 21, 2019, a group of cases of viral pneu monia had been identified in Wuhan, a metropolitan city in the province of Hubei, China, caused by a new single-stranded RNA virus (SARS-CoV-2) of possible animal origin that has been extensively spreading in humans and causing respiratory, enteric, hepatic and neurological diseases1,4. In February 2020, the World Health Organization designated the disease caused by this virus as COVID-19, which stands for coronavirus disease 20191; COVID-19 has progressively spread and was declared a pandemic on March 11, 2020. COVID-19 has severe impact in terms of morbidity, morta lity and costs2.

Worldwide, approximately 15 million confirmed cases of CO VID-19 have been reported on all continents, except Antarc tica3. Latin America and the Caribbean represent the current epicentre of the pandemic due to the vulnerability of some health care systems and considerable heterogeneity in eco nomic, political and social development4. Over 6.2 million people have been affected by the disease in this region; Bra zil is the most affected country, followed by Peru, Mexico, Chile, Colombia and Argentina3. SARS-CoV-2 disease (CO VID-19) is predominantly manifested as a lung infection with a range of symptoms characteristic of a mild upper respira tory tract infection; however, 15 to 20% of patients develop severe pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and 5% of patients develop critical illness associated with shock, cytokine release syndrome, coagulation disorders with consequent multiple organ failure and death5-7. The de mographic, clinical and laboratory risk factors associated with worse outcomes have been described in the literature; however, the frequency and importance of these factors in the Latin American population have not been described. Our study aims to analyse the clinic characteristics, risk factors and evolution of the first group of hospitalised patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection in 5 institutions in Colombia.

Materials and method

Design and population

This is a retrospective longitudinal study of adult patients (> 18 years) diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 [+] confirmed by real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of a nasopharyngeal secretion sample hospitalised in 5 high-complexity hospitals in Colombia and discharged from March 1 to May 30, 2020. The five hospitals were Clí nica Universitaria Colombia (Bogotá, Colombia), Clínica Santa María del Lago (Bogotá, Colombia), Clínica Reina Sofía (Bogo tá, Colombia), Clínica Iberoamérica (Barranquilla) and Clínica Sebastián de Belalcazar (Cali, Colombia). Patients were recrui ted consecutively based on compliance with inclusion crite ria. Demographic variables, comorbidities, signs and symp toms at admission, chest images, laboratory test, biomarkers, treatment schedules, complications and discharge condition (alive or dead) were extracted from the clinical history.

Outcomes

The main outcome was the 30-day in-hospital mortality rate; in addition, the composite outcome, defined by a critical care requirement, mechanical ventilation and death, was con sidered. Other outcomes of interest included frequency of complications, variability in biomarkers and established drug treatment schedules.

Ethical: The research was approved by the ethics committee. It is a risk-free study due to its retrospective observational design.

Data analysis

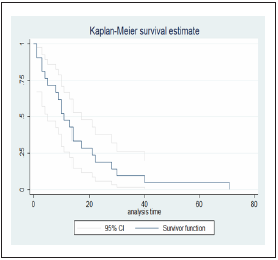

The quantitative variables were analysed using frequency, mean and variance; the categorical data were analysed using proportional ratios. Bivariate analysis was performed using X2-squared statistic tests for independence in 2x2 tables and Fisher’s exact test for comparison. Hypotheses were confir med or rejected at p<0.05, which was considered statistica lly significant. Survival functions of time until the event were used to analyse the complications and lethality by Kaplan- Meier curves starting from diagnosis at admission. Explora tory analysis of the associations between mortality and prog nostic biomarkers at admission was performed by estimating the relative risk (RR) and odds ratios (OR) with 95% confiden ce intervals (95% IC).

Based on the collected information, the score on the national early warning score (NEWS) risk scale8), Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) (9 corrected for age, APACHE II10 and the sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) (11 were estimated for each patient. All analyses are presented according to variable type.

The data analysed during the study are available http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/cwrd5ysmzp.1.

Results

A total of 44 patients were admitted from March to May 2020 to 5 high-complexity hospitals in Colombia. The median age of the patients was 62 years (IQR: 53-72 years), and 79.5% of the patients were older than 50 years. Table 1 summarises the main demographic and admission characteristics of patients with SARS CoV-2/COVID-19 infection.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with COVID-19

BMI: Body Mass Index; HBP: high blood pressure; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; Dis. disease; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; CRP: C-reactive protein; ALT: alanine transaminase; AST: aspartate transaminase; CAT: computerised axial tomography. aIncludes apnoea, heart failure, neoplasms, asthma, arthritis and chronic liver disease.

The median time between the onset of the symptoms and the first consultation at the emergency department was 7 days (IQR: 3-8 days). Systemic symptoms (general malaise, fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia and general deterioration) were reported in 95.5% of the patients, followed by cough (93.2%), high respiratory symptoms (odynophagia and rhinorrhea) (90.9%) and low respiratory symptoms (dyspnoea, retraction and wheezing) (90.9%). Gastrointestinal symptoms, such as diarrhoea, nausea, abdominal pain and emesis, were present in 45.5% of the patients. Anosmia was reported in 9.1% of the patients. Fever was reported by 70.5% of the patients but was documented on admission only in 20.5%.

The results of the majority of admission laboratory tests were normal. However, 36.4% of the patients had lymphopenia at admission and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels higher than 10 mg/L; 25% of the patients had lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels higher than 349.9 U/L, and 56.8% of the patients had LDH levels higher than 214 U/L; 16% of the patients had D-dimer levels higher than 1,000 ng/ml; 18.2% of the patients had troponin levels higher than 14 ng/L; and 13.6% of the patients had ferritin levels higher than 1,000 ng/mL. The temporal trend estimates of CRP, D-dimer and troponin are presented in Figure 1. During follow-up, CRP levels increased according to the reports of the first 4 measurements, and the levels decreased after peaking; the D-dimer levels increased regardless of the outcome of the patients, but the highest values were observed in deceased patients. The follow-up of the troponin levels indicated differential results between living and deceased patients, with the troponin levels increa sing slightly over time in living discharged patients.

Figure 1 Time-dependent changes in C-reactive protein, D-dimer and troponin levels in hospitalised patients whith SARS CoV-2/COVID-19

In the follow-up period, 21 deaths occurred, representing a 30- day mortality rate of 47.7%; median time to fatal outcome was 11 days (IQR: 5-21) (Figure 2), and the average time was 15.9 days. A composite outcome (intensive care unit (ICU), mechani cal ventilation and death) was present in 36.4% of the patients and was more frequent in men from 70 to 79 years of age with grade I obesity, a history of smoking, high blood pressure and dyslipidaemia. A total of 84.1% of patients required support in the ICU for a median of 2 days (IQR: 1-4) from admission to the emergency room to transfer to the ICU; 70.5% of the patients required invasive ventilator support for a median of 2 days (IQR: 1-4). A total of 27.3% patients required renal support therapy (RST), which corresponds to 12 patients with severe pneumonia. The outcomes are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Outcomes and complications

IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation; ICU: intensive care unit; ARDS: Acute respiratory distress syndrome

The most common complications included ARDS (65.9%), sep tic shock (61.4%), cardiovascular complications (54.5%), multi ple systemic organ failure (52.3%), acute kidney injury (45.5%) and neurological complications (45.5%). A total of 72.2% pa tients with severe pneumonia had ARDS, and 51.4% of these patients died. All fatal cases had cardiovascular complications. A total of 55% of the patients with acute kidney injury died.

Exploratory analysis of mortality associated with biomarkers at admission indicated a higher risk associated with troponin levels higher than 14 ng/mL (RR: 5.25; 95% CI 1.37-20.1, p = 0.004), D-dimer levels higher than 1000 ng/ml (RR: 3.0; 95% CI 1.4-6.3) and CRP levels higher than 10 mg/L (RR: 5.5; 95% CI 0.42-1.6, p = 0.009); the results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3 Relative risk and odds ratio of death according to biomarkers of risk at admission

RR: relative risk; p: p-value; OR: odds ratio; NC: not calculated

Estimation of the risk scales at admission involved the CCI, which could be calculated for all patients; 32 had sufficient information for SOFA and APACHE-II, and 43 had enough in formation for the NEWS scale. The median NEWS value was 7 points (IQR: 5-8), the median SOFA score was 6 points (IQR: 2.5-10), the median APACHE-II score was 25 points (IQR: 15- 40), and the median CCI was 2 points (IQR: 1-4). Nine patients were classified with zero points on the CCI, 15 patients had CCI from 1 to 2, 11 patients had CCI from 3 to 4, and 9 pa tients had CCI of 5 or higher. According to the American Tho racic Society (ATS) classification, 96.6% of the patients had severe pneumonia, and the median time to death in these patients was 13.5 days (IQR: 8.5-21.5 days).

Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection was achieved by imple mentation of the schemes based on antibiotics (90.9%) and an timalarial agents in combination with antiviral agents (72.7%). Two patients who had positive indications for influenza were treated with oseltamivir, and both patients died. A total of 37 patients had severe pneumonia; 30 of these patients received hydroxychloroquine plus ritonavir/lopinavir, and 36 patients were treated with antibiotics. In addition, 11 of the deceased patients received hydroxychloroquine plus ritonavir/lopinavir, and 19 patients received antibiotics. In patients with a com posite outcome, 56.5% received hydroxychloroquine plus an antiviral agent, 62.5% received chloroquine plus an antiviral agent, and 93.8% received an antibiotic.

The median overall hospital stay was 13 days (IQR: 8-22.5 days). The average hospital stay was 6.4 days (SD: 6.8 days), and the average ICU stay was 11.6 days (SD: 11.5 days).

Discussion and conclusions

In Colombia, the first case of SARS-CoV-2 infection was re ported on March 6, and the first death occurred 10 days later; however, the clinical course of patients with SARS-CoV-2 in fection has not been documented in Colombia. By mid-July 2020, 218,000 confirmed cases had been registered in Colom bia, and 10% of the cases required admission to the hospital12.

The baseline characteristics of the study population are simi lar to those of previously published epidemiological studies with a slightly higher age of hospitalisation than that repor ted in the initial studies in China (49 years in the initial Huang report7 and from 55 to 56 years in the subsequent reports by Xu13 and Wang14). In subsequent studies in Italy, Spain and New York, the median age of the population was the same as that reported in our study6,15,16.

In patients admitted 7 days after the onset of the symptoms, the most common complaints included general discomfort, cough, fatigue, dyspnoea and, to a lesser extent, odynophagia, vomiting, headache and anosmia, which matches the symp toms reported in the studies in China7,13,14. It should be noted that in our group of patients, fever was documented only in 20.5% of the patients on admission; however, 70% had fever previously. The frequency of fever varies among the studies; in the largest cohort in Europe, fever was present in 45.4% of the cases15, while in China, fever was present in more than 80% of the cases17-19. In a study of 1,099 hospitalised patients, Guan et al. reported the presence of fever in 44% of the cases at hos pital admission20. A total of 93% of the patients had a cough in our study; in other studies, the incidence of cough varied from 48.7% to 65.5%15,17,19,21. Dyspnoea was present in 85% of the patients with severe pneumonia, in contrast with the meta-analysis and systematic review of Zhao et al., which reported dyspnoea in 44.2% of patients with severe pneumonia (95% CI: 7.8-80.6) and in 5.7% of patients with non-severe infection (95% CI: 0-10.7%)22; moreover, dyspnoea has been reported as a marker of severe and progressive disease23-25.

Strikingly, anosmia was only reported by 4 people; however, Menni et al. reported that loss of smell can be a frequent symptom, and anosmia accompanied by fever, fatigue, per sistent cough, diarrhoea, abdominal pain and loss of appetite can predict COVID-19 with a specificity of 0.83 (95% CI: 0.81- 0.86) and a sensitivity of 0.55 (95% CI: 0.50-0.59) (26. It is likely that the availability of additional information on the anamne sis of the disease will place a higher emphasis on this symp tom and that the incidence of anosmia will be higher than that described in the present study. Similarly, gastrointestinal symptoms occurred in less than 30% of the cases; however, it has been reported that diarrhoea and nausea can precede fever and lower respiratory tract symptoms27.

Older adults and people with pre-existing comorbidities, parti cularly cardiovascular diseases, high blood pressure and diabe tes mellitus, have a significant risk of progression, complications and death28-30. In our study, 79.5% of the patients were older than 50 years, and 75% of the patients were affected with more than 2 comorbidities; the most frequent comorbidities inclu ded obesity, high blood pressure, dyslipidaemia, diabetes and a history of smoking. The overall in-hospital mortality of the patients over 60 years of age was 66.7%. These data are similar to the results of Liu et al., who reported a higher risk of disease progression and death in people older than 60 years (OR: 8.5; 95% CI: 1.6-44.8), with a history of smoking (OR: 14.2; 95% CI: 1.5-25) and with respiratory failure (OR: 8.7; 95% CI: 1.9-40) (31. Similarly, Wu et al. reported a higher case-fatality rate among older adults: (≥80 years: 14.8%; 70-79 years: 8.0%; 60-69 years: 3.6%) and among patients with comorbidities, including 10.5% for cardiovascular diseases, 7.3% for diabetes, 6.3% for chronic respiratory diseases, 6.0% for high blood pressure and 5.6% for cancer29. In a cohort study in the United States, the United Sta tes Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) COVID-19 response team reported higher mortality in people aged ≥85 years (range 10%-27%), followed by 3%-11% mortality for ages from 65 to 84 years30. As of the current date (July 20, 2020), among all cases of death in Colombia (6,736), the most frequent comorbidities were diabetes mellitus (26.2%), chronic kidney di sease (14.8%) and cancer (10.3%). A substantial increase in mor tality was observed in older people12.

Unlike reported previously in other studies, 37 (84.1%) of 44 patients in the present study developed severe pneumonia and required intensive care management, and 31 patients re quired mechanical ventilation within 2 days after admission to the hospital. These data differ from data in preliminary reports from China, which indicated a range of 26% to 32% of patients requiring ICU management13,14,28. In the United States, the CDC reported an incidence of ICU admission from 7 to 26%30, while in Italy, 12% of all detected cases of COVID-19 and 16% of all hospitalised patients were treated in the ICU32,33.

The high incidence of ICU admission in our cohort of hospi talised patients may be related to a higher severity of clini cal manifestations at admission; the majority of the patients were admitted 1 week after the onset of symptoms, which corresponds to the period of maximum alert for the risk of clinical deterioration7,14,34,35. This situation has important im plications for health care systems. The overall data for Co lombia revealed that approximately 55% of deaths occurred within the first 10 days after hospitalisation12, which reaffirms this finding and indicates a need for early detection of the patients at risk of complications. The mortality of the patients admitted to the ICU was 51.3%; however, mortality varied from 39% to 72% depending on the study and is associated with age, comorbidities and complications27,28,34,35.

Similar to the cohorts reported in the previous studies, common laboratory test abnormalities of hospitalised patients with CO VID-19 included lymphopenia and elevated levels of CRP, LDH and troponin14,20,36. Lymphopenia is a marker of impaired cellular immunity and has been reported in 67-90% of the patients with COVID-197,37,38. Elevated levels of D-dimer at admission, as in our patients, have been reported in 46% of hospitalised patients with a longitudinal increase during the hospital stay; in our stu dy, D-dimer levels higher than 1000 ng/mL were significantly associated with an increased risk of mortality20,28,34,39.

Similar to the previous reports, the radiographic findings mainly included ground-glass opacities and parenchymal con solidations, and only a single patient had normal chest radio graphy; however, reports of normal chest radiography at the beginning of the disease are frequent20,40. On admission, 11 of the 44 patients in our cohort had a normal chest compu ted tomography (CT) result, and 9 of the patients had severe pneumonia with bilateral ground-glass opacity, thus confir ming previously reported observations41-43. Considering the variability of the radiographic findings in the CT due to the evolution time and severity of the disease, the American Colle ge of Radiology does not recommend CT as a first-line test for the diagnosis of COVID-1944, and the Radiological Society of North America has suggested categorisation of the images to standardise the interpretation and reporting45. These guideli nes match the observations of the previous studies in critically ill patients20,46-48. In patients who developed severe pneumo nia, the mean time to dyspnoea ranged from 5 to 8 days, the median time to ARDS ranged from 8 to 12 days, and the mean time to admission to the ICU varied from 10 to 12 days7,14,34,35.

Similar to previous reports, ARDS was the main complication in our patients. ARDS developed in 65.6% of the patients, and 26 patients required mechanical ventilation with 65.5% mortality, which was increased concomitant to the severity of the disease; older patients with comorbidities had a higher probability of mortality5,39,49. Acute kidney injury was present in 45.4% of the cases, and renal replacement therapy was in dicated in 27.2% of the cases; this is a frequent complication detected in approximately 20-40% of the patients admit ted to the ICU5,50,51. Therefore, prevention of nephrotoxicity and early detection are very important to establish a timely treatment that impacts morbidity and mortality.

The majority of the patients were treated with antiviral drugs and antibiotic therapy according to the recommendations approved and enforced during the period of the study. In vitro studies with chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine have shown antiviral activity; however, the available evidence has not confirmed the benefits of these antimalarial drugs in patients with SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 infection52-54. Support measures and comprehensive management in hospitalised patients can reduce complications and mortality55.

Our study has certain limitations: (i) the study has inherent limitations by design since it is a purely descriptive study in a small sample without any permissible inference to the general population; however, it provides an overview of the epidemiological situation in hospitalised patients with SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 infection in Latin America, mainly in Co lombia; (ii) at the moment of data collection, Latin America was not at the epicentre of the pandemic; (iii) in the case of some estimates, information was not available for all pa tients, which may incur a bias because availability of this in formation can be related to more severe manifestation of the disease and/or transfer to the ICU, where strict monitoring of the patients is performed.

Finally, the clinical course of SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis confirmed by RT-PCR in Colombian patients admitted to a high-complexity hospital was similar to that reported in the literature; however, the population was characterised by a more advanced stage of the infection. This report provides a snapshot of the pattern of the pandemic in Colombia and Latin America to guide strategic and clinical decision making and public health policies to ensure reduced potential impact for patients, institutions and the health system.