Introduction

Exotic species are those displaced from their historical natural environment to other localities with or without human intention (Invasive Species Specialist Group - ISSG, 2000). They become invasive when they manage to establish and reproduce in the new area generating an alien population, which can cause strong ecological pressures on the local biodiversity, especially in mega-diverse countries (Mooney & Hobbs, 2000; Frehse et al., 2016). The effects caused by the action of invasive species include the migration of local species, the transmission of pathogens, and the local extinctions, among others (Clavero & García-Berthou, 2005; Díaz et al., 2020; Milardi et al., 2020). This problem has increased in recent years due to cargo shipments associated with market globalization (Levine & D'Antonio, 2003; Meyerson & Mooney, 2007) and human migrations (Veitch & Clout, 2001; Hulme, 2009; Lockwood, et al., 2013) evidencing the strong relationship between industrial development and the establishment of foreign species with clear examples in Asia and America (Lin, et al., 2007; Mayerson & Mooney, 2007; Ramírez-Albores, et al., 2019).

With more than 150 currently recognized species, geckos of the genus Hemidactylus (Lacertilia: Gekkonidae) are among the most diversified and widely distributed lizards in the world (Carranza & Arnold, 2006; Giri & Bauer, 2008; Uetz, et al., 2020). Some taxa have been recognized as potentially invasive species (e.g., H. angulatus, H. frenatus, H. garnotii, H. mabouia, H. platyurus, H. parvimaculatus, and H. turcicus) causing the decline of local species including other native lizards, especially in island ecosystems (Case, et al., 1994; Dame & Petren, 2006). Due to their establishment and naturalization capabilities, H. frenatus originally native to Asia and the Indo-Pacific region, is one of the most successful invasive geckos (Bauer & Baker, 2012) with the largest distribution within the genus (Case, et al., 1994; Carranza & Arnold, 2006). Similarly, the Indo-Pacific Gecko H. garnotii, native to Tahiti in French Polynesia, is widely distributed in the tropical and subtropical zones of the Asian Pacific with well-established populations in transformed environments of the American continent (Carranza & Arnold, 2006). Furthermore, H. mabouia, originally distributed in Central and Eastern Africa (Kluge, 1969; Carranza & Arnold, 2006), has colonized and established in West Africa, the Caribbean Region, part of South America, and the state of Florida in the USA (Krysko & Daniels, 2005; Carranza & Arnold, 2006; Rodder, et al., 2008).

In Colombia, there are recent records of the establishment of four Hemidactylus species (H. angulatus, H. frenatus, H. garnotii, and H. mabouia in continental and insular localities including remote regions, such as the Amazon basin (Caicedo-Portilla & Dulcey-Cala, 2011; Vásquez-Restrepo & Lapwong, 2018; Caicedo-Portilla, 2019). Rapid dispersion of the alien geckos introduced in Colombia has been elucidated through the review of specimens in collections and photographs in the wild (Castaño-Mora, 2000; Vásquez-Restrepo & Lapwong, 2018). Additionally, atypical records of native Colombian reptiles outside their normal distribution ranges have been scarcely documented in the country (Gutiérrez, et al., 2012). One of the most common causes of unusual records of reptiles in the country is their accidental human transportation, but not all cases are the consequence of an apparent human intervention (Marín, et al., 2017). Some examples of unusual distributional records not yet considered exotic for the country include the introduction of the spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus) on San Andrés and Providencia Islands (Forero-Medina, et al., 2012) and recent records of the yellow-headed gecko (Gonatodes albogularis) in eastern Colombia (Caicedo-Portilla & Gutiérrez-Lamus, 2020).

The reports of alien species are important to explore possible risks caused by their introduction in the areas they colonize (Rodríguez, 2001; Abarca, 2006). This is key for highly affected ecosystems by habitat transformation such as the Andean cordilleras, (Armenteras, et al., 2003) concentrating the highest proportion of roads and human settlements in the country (Acevedo, et al., 2009). Similarly, documenting unusual records of native species outside their known ranges but clearly not representing range extensions is relevant to evaluate how populations may establish in other areas with or without human intervention. In this study, we present new records of H. frenatus H. garnotii, and H. mabouia from the Central Andes of Colombia and update their distribution. Additionally, we provide evidence of an atypical record of Gymnophthalmus speciosus (Hallowell, 1861) in a paramo ecosystem at 4.000 m.a.s.l.

Methodology

To update the distribution of Hemidactylus frenatus, H. garnotii, and H. mabouia we reviewed specimens deposited in the reptile collections of the Centro de Museos, Museo de Historia Natural, Universidad de Caldas (MHN-UCa-R) in Manizales, Universidad de Los Andes (ANDES-R) in Bogotá, and photographs of specimens housed at the herpetological collection of the Universidad del Quindío (UQ) in Armenia, Colombia. We also included photo-vouchered records obtained by us during 2019 and 2020 in the inter-Andean Cauca River basin in the departments of Caldas and Cauca, as well as records in the literature (Renjifo & Lundberg, 1999; Carranza & Arnold, 2006; Angarita-Sierra, 2010; Cárdenas-Arévalo, et al., 2010; Vanegas-Guerrero, et al., 2016; Díaz-Pérez, et al., 2017; Mueses-Cisneros & Caicedo-Portilla, 2018; Medina-Rangel, et al., 2019; Díaz-Pérez, et al., 2020), and museum databases.

To identify the reviewed specimens, we used the taxonomic keys of Krysko & Daniels (2005) and other morphological traits (Kluge, 1969; Zug, et al., 2007; Caicedo-Portilla & Dulcey-Cala, 2011; Vásquez-Restrepo & Lapwong, 2018). The characters examined were: (1) the arrangements of the subdigital lamellae of fingers and toes, especially the fourth toe; (2) the fourth toe length; (3) the body size (snout vent-length and tail length, SVL and TL, respectively) (Table 1S,https://www.raccefyn.co/index.php/raccefyn/article/view/1356/3036) taken with a dial caliper to the nearest 0.01 mm; (4) the shape and arrangement of the dorsal scales; (5) the arrangement of the second chin shields, and (6) the disposition of the scales on the tail.

Additionally, we present an unusual (human transported) record of the golden spectacled tegu, G. speciosus based on one specimen found in a paramo ecosystem in the department of Caldas, Central Andes of Colombia. The specimen died after being captured and was preserved in 70% ethanol (MHN-UCa-R 431). We corroborated its identity by comparing the size, shape, and number of head scales, as well as its lack of eyelids (Avila-Pires, 1995; Hernández-Ruz, 2006). To confirm that MHN-UCa-R 431 specimen was an unusual record, we searched for additional localities in the literature (Meza-Joya & Ramos-Pallares, 2015) and listed the ecosystems and elevational range where the species has been documented.

Results

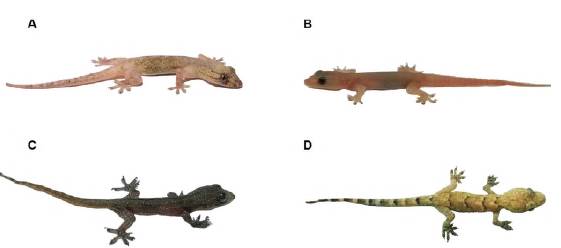

We updated the distribution of the exotic house geckos Hemidactylus frenatus (Figure 1A), H. garnotii (Figure 1B), and H. mabouia (Figure 2A) based on several new localities, as well as historical records. We also present an atypical record of the golden spectacled tegu Gymnophthalmus speciosus (Figure 2B) in the Central Andes of Colombia. We found that H. frenatus is widely distributed in Colombia with records in all regions and 30 of the 32 departments of the country (Table 2S,https://www.raccefyn.co/index.php/raccefyn/article/view/1356/3037). We identified three specimens of H. frenatus (MHN-UCa-R 213, 525, 591) for the Central Andes of Colombia filling gaps in the distribution of the species in the Cauca and Magdalena river basins. Based on photographic records, we detected the presence of H. frenatus in two additional localities on the western slope of the Central Cordillera in the departments of Caldas, Cauca, and Risaralda (Figure 3A). The photographed specimens were recorded vocalizing at night (around 20:00 hours) on the walls of human settlements and identified as H. frenatus due to the presence of flat dermal tubercles on the dorsal surface of the body, as well as spines and protuberances on the tail (Figure 3B). For H. garnotii, we only found records from the Colombian Cauca River basin (Figure 1B). We identified two specimens of H. garnotii (MHN-UCa-R 214, 511) representing the southernmost known records in the Central Andes of Colombia. They come from Caldas and Risaralda (Figure 3C) and are the first confirmed records for both departments. For H. mabouia (Figure 3D), we found records for the Cauca River basin based on photographs obtained in the cities of Popayan (Cauca) and Armenia (Quindio) (Figure 2A). In Popayan (Figure 2B), the records corresponded to specimens found inhabiting houses in the peri-urban area in 2020 and are the first documented for the department.

Figure 1 Distribution of two exotic Hemidactylus in Colombia. A. Hemidactylus frenatus\ black dots denote records in literature and red dots show new records for the country. B. Hemidactylus garnotii: black triangles represent records in the literature and orange triangles are the new records extending its distribution in the Central Andes of Colombia.

Figure 2 Distribution of an exotic Hemidactylus and an unusual record of a golden tegu, Gymnophthalmus speciosus, in Colombia. A. Hemidactylus mabouia: black rhombus are records in the literature and the red ones represent new records from the departments of Quindío and Cauca in the Central Andes of Colombia; question marks denote dubious records of H. mabouia in international museums. B. The unusual (transported) record of G. speciosus (red star) in paramo ecosystems of Colombia. Black stars show available records in the lowlands (up to 1,000 m.a.s.l.) in Colombia.

Figure 3 Records of three exotic house geckos from Colombia. A. Hemidactylus frenatus (SVL 48.10 mm) found in human houses in the municipality of Pereira, department of Risaralda (MHN-UCa-R 591). B. Hemidactylus frenatus photographed in the municipality of Chinchiná, department of Caldas. C. Hemidactylus garnotii juvenile (SVL 21,87 mm) from the municipality of Manizales, department of Caldas (MHN-UCa-R 511). D. Hemidactylus mabouia photographed in the municipality of Popayán, department of Cauca

The records from Armenia are based on photographs wrongly reported in the literature as H. frenatus by Vanegas-Guerrero et al., 2016; Figure 3B while the specimen really corresponds to H. mabouia. A preserved specimen (UQ-0269) collected in the department of Quindío also belongs to this species. The H. mabouia photographed presents the dorsal pattern of the species consisting of V-shaped bands with the vertex of each band directed posteriorly and dark brown posterior margins of the bands (Figure 3D). The fourth toe of the specimen UQ-0269 presents lamellae that do not reach its base, a morphological characteristic of H. mabouia. We also found two unconfirmed records of H. mabouia from the departments of Santander and Vaupes in museum databases (Table 2S,https://www.raccefyn.co/index.php/raccefyn/article/view/1356/3037) that we include here as dubious.

Furthermore, we observed previous suggested external differences that help to differentiate between H. garnotii and H. frenatus specimens: The chin shields are not in contact with the infralabial scales in H. garnotii but they do in H. frenatus. The dorsal surface of H. garnotii presents homogeneous scales along the body vs. flat dermal tubercles and some intermixed granulations in the dorsal surface of H. frenatus. The tail of H. garnotii has cylindrical serrated margins without spines or tubercles vs. serrated margins in the tail with spines or tubercles in H. frenatus (Krysko & Daniels, 2005). We identified additional external differences between both species including the number of sub-digital lamellae on the fourth digit (8 to 13 in H. garnotii vs. 7 to 9 in H. frenatus) and wider lamellar structures in H. frenatus than in H. garnotii (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Plantar view of the forefoot (manus) of (A) Hemidactylus garnotii (MHN-UCa-R 416) and (B) Hemidactylus frenatus (MHN-UCa-R 591) showing the differences in the structure of subdigital lamellae. Scale: 2 mm

Finally, we present a record of G. speciosus based on an individual found alive on December 14, 2018, 12:00 h, in the parking lot in "Brisas", Los Nevados National Natural Park (4.937886° N, -75.349758° W, 4,057 m.a.s.l.). The locality is part of a paramo ecosystem in Caldas Central Andes. The record is unusual as this species is known only in the lowland (up to 900 m.a.s.l.) of the Caribbean, Orinoquia, and the dry Inter-Andean valleys of the Magdalena and Cauca rivers. Our literature search showed that the closest elevational records are 3.100 m away from the locality where MHN-UCa-R 431 was found. Considering that the lowest paramo ecosystems in Colombia start at elevations around 3.500 m.a.s.l in the Central Andes (Cuatrecasas, 1958), and the absence of confirmed G. speciosus records from sub-Andean and Andean ecosystems (1,000-3,500 m.a.s.l.), it is very unlikely that Los Nevados, Caldas, is part of the normal range of the species. We discarded that the specimen MHN-UCa-R 431 might represent a different species due to the morphological characters that cast no doubt on its identification including the small-size (SVL 34,65 mm), the lack of eyelids, the presence of a large pentagonal scale in the parietal area, two internasal scales connected in their medial part, large pre-frontal scale, small and pentagonal frontal scale, and seven supralabial and five infralabial scales (Figure 5).

Discussion

Unintentional human transport of fauna may be favored by characteristics of an organism's natural history, such as the morphology, the boldness, and the exploratory habits displayed by animals used to living in urban environments (Chapple, etal., 2012). These behaviours lead urban-adapted animals to interact with commonly transported products like fruit thus dispersing to and invading new territories (Chapple, et al., 2011). Likewise, species living in an area close to another with high levels of anthropic transformation are more likely to be transported by humans (Hulme, 2009). In our study, two of the new records of Hemidactylus were reported in areas of high vehicular flow (municipal transport terminal, parking lot), and their presence there probably responds to the reasons previously exposed.

The origin of H. garnotii individuals in Colombia is still unclear, however, Vásquez-Restrepo & Lapwong (2018) suggested their possible arrival from Florida, USA, where the largest population of this species is found. Florida represents a mandatory loading-shipment point between North and South America and geckos can be unintentionally transported. Similarly, the arrival of H. frenatus to the country may have occurred through ports in the Caribbean or our border with Venezuela where this species was first registered in the year 2000 (Caicedo-Portilla & Dulcey-Cala, 2011; Torres-Carvajal, 2015). As for H. mabouia, its arrival to the Amazon region probably followed the pattern of human expansion in this region (Avila-Pires, 1995). At a regional scale, it is still unknown how and when these species arrived and if all three are successfully established in the Central Andes of Colombia.

In Colombia, H. garnotii was recently recorded in the department of Antioquia from museum specimens collected in the early 2000 and 2010s (Vásquez-Restrepo & Lapwong, 2018). Based on our results, H. garnotii is registered for the first time for the departments of Caldas and Risaralda in the country's Central Andes in similar habitats to those reported in the department of Antioquia (Vásquez-Restrepo & Lapwong, 2018). The new records extend the distribution in about 150 km linear to the south from the nearest known locality (municipality of Caldas, department of Antioquia) (Vásquez-Restrepo & Lapwong, 2018). However, the records of this species seem to be isolated and further fieldwork should be done to define if the species is well established and if it occupies a different niche with respect to native geckos (Perella & Behm, 2020). With our records, H. garnotii is currently known in six localities in the Colombian Andes (Figure 1B) (Table 2S,https://www.raccefyn.co/index.php/raccefyn/article/view/1356/3037).

Hemidactylus frenatus is the most common exotic gecko in Colombia (Caicedo-Portilla & Dulcey-Cala, 2011). Nevertheless, ours constitute the first documented records for the Cauca River basin on the western opposite slope in the Central Cordillera (Caicedo-Portilla & Dulcey-Cala, 2011) evidencing that the species is extending its distribution to the west and southern part of the Colombian Andes and is likely well established currently. Including our records, H. frenatus is present in 99 localities in 30 of the 32 departments of Colombia and only the Chocó and Guainía have no confirmed records for this species. This shows a rapid dispersal of the species within the territory and our inability to monitor it at the same speed considering that previous papers on this species in Colombia included only records for 20 of its 32 departments (Caicedo-Portilla & Dulcey-Cala, 2011). We believe that the absence of records of this species in Chocó and Guainía may be the result of limited fieldwork in those areas.

Hemidactylus mabouia is mainly distributed east of the Andes in transformed habitats of the Colombian Amazon (Medem, 1968; Ayala, 1986). The presence of H. mabouia in the cities of Armenia and Popayán is the first documented in the Colombian Andes and the second known for a trans-Andean locality (Carvajal-Campos & Torres-Carvajal, 2010). The H. mabouia records from the department of Santander in museum databases (Table 2S,https://www.raccefyn.co/index.php/raccefyn/article/view/1356/3037) need to be reviewed to confirm whether the species is most widespread in trans-Andean Colombia. An additional record from the department of Vaupés in museum databases (Table 2S,https://www.raccefyn.co/index.php/raccefyn/article/view/1356/3037) also needs to be verified. Based on the specimens we reviewed the species is present in the department of Vaupés (Table 2S,https://www.raccefyn.co/index.php/raccefyn/article/view/1356/3037) but this unconfirmed record dates from 1967. If confirmed, it would give us valuable information about the historical dispersion of the species in Colombia.

Besides the exotic geckos documented, the finding of the golden spectacled tegu G. speciosus in a paramo ecosystem is most certainly a consequence of accidental transport of the individual from the lowland ecosystems where the species inhabits (Meza-Joya & Ramos-Pallares, 2015). The fact that all the previously known distributional and ecological information shows that the species is a typical lowland reptile supports our assertion. G. speciosus distribution in Colombia comprises the lowland dry forests zones of the Caribbean region, the moist forests across inter-Andean valleys, and the Orinoquian savannahs below 900 m (Hernández-Ruz, 2006; Meza-Joya & Ramos-Pallares, 2015), which means that this unusual record is almost 3.000 m above the highest known elevational record and very likely its origin was the Magdalena Valley where the closest confirmed populations have been identified (Meza-Joya & Ramos-Pallares, 2015). This exchange of biota between lowlands and Andean areas may be more common than previously thought due to the high vehicular flow to which this region is exposed (Jarrin-V, 2003). Therefore, documenting unusual records is relevant to evaluate possible routes of colonization or unintentional transport of exotic species. G. speciosus was not previously recorded for the department of Caldas and our report should be handled with caution. There is a high probability of finding lowland populations of G. speciosus in Caldas in locations near to the Magdalena River basin where this species occurs (Meza-Joya & Ramos-Pallares, 2015).

Finally, additional sampling should be carried out in the main cities of the Colombian Andes to verify whether species of exotic geckos have established there with viable populations. The efforts should also consider the effects that these invasive species can generate on the ecological responses of local assemblages (see Perella & Behm, 2020, for a discussion on this topic). The study of the biotic and abiotic factors that influence the colonization of exotic geckos in South American biomes, especially across the Andes, is urgent. Molecular studies are required to shed light on the origin of the foreign species registered in the country and to establish the possible genotypic variations of these populations throughout the national territory.