Introduction

The respiratory disease caused by the novel coronavirus has been named "CoronaVirus Disease 2019" (COVID-19), causing concern mostly among risk groups, including pregnant and postpartum women until day 14. In Brazil, the lethality rate stemming from the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV-2), caused by COVID-19, has led to 544 deaths in 2020, with a mean weekly rate of 12.1. By May 2021, a total of 911 deaths had been reported, with a mean weekly rate of 47.9, indicating an alarming increase 1,2.

In the Americas, a total of 1,271 deaths among pregnant women who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 had been reported between January 2020 and May 2021, with records in Mexico (334), Peru (114), the United States of America (99), Colombia (69), and Argentina (56). Although lower than those reported in Brazil, these numbers corroborate the impact of the virus in the pregnancy-postpartum cycle 3.

In addition to the concern over the outcome of the disease in the maternal body, other factors include the family members' health 4,5, the baby's health, changes in maternal and child health services, the presence or absence of a companion during delivery and postpartum, and the scarcity of reliable information 4. Postpartum women are at exceptionally high risk for mental health disorders during the pandemic 6; therefore, these maternal concerns may contribute to increased psychological distress 4,7-9, with evidence that women in the perinatal period face symptoms of stress, anxiety (60 %), and depression (12 %) 10, along with signs of likely increased depression 11, anxiety 1,12,13, and anhedonia 12, motivated by the perceived risk of COVID-19 12.

Social distancing due to COVID-19 implies decreased intimate contact, generates uncertainty and anxiety regarding the pandemic context 14, and the perception that perinatal women are at greater risk due to COVID-19 compared to non-pregnant women 15 increases their fear regarding childbirth 14,15. A possibility exists for increased depression and anxiety symptoms during the perinatal period during pandemic lockdown 16, which may have short- and long-term consequences, highlighting the caution required for the mental health of this population 7.

Furthermore, the current pandemic increases the likelihood of postpartum depression (PPD). According to a study, there was an incidence of 56.9 % of depression symptoms in Chinese women where age, abortion history, and perceived stress were influential factors, and the demands related to parenting guidance (78 %), protection of the mother-child dyad (60.3 %), and feeding (45 %) were listed as care needs. In addition, this study found an increased need for psychological assistance for postpartum women who were depressed compared to those who were not depressed 12.

Against this backdrop, this study is substantiated by the urgent need to synthesize the theoretical and reflective framework on the mental health of postpartum women, understand the scope of this issue,vand, thus, contribute to quality care in line with demand-orientedvstrategies.

Postpartum is considered a period of unique and specific characteristics, both biologically, emotionally, and socially 17; it starts after childbirth and includes the restoration of the female organism, and, consequently, it has an imprecise time limit. The "unexpected conclusion" was selected for this review 18.

Considering the above, this article aims to identify and analyze the scientific evidence on the mental health of postpartum women during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

This integrative review, a method that widely synthesizes the results of national and international research, provides relevant, timely evidence that contributes to clinical practice, the production of critical knowledge, and future studies 19,20 by pointing out research gaps 20, meeting the need for knowledge created by the pandemic.

We followed six steps 19,21. The first, "Selection of the Guiding Question," was structured with the PICo strategy, where P stands for population (postpartum women), I for interest (mental health), and Co for context (COVID-19 pandemic). It led to the question "What is the scientific evidence on the mental health of postpartum women during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic?"

The databases and search strategies were listed in the second step, "Sampling." An author performed the digital search on November 24th, 2020, through the Portal de Periódicos da Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Capes), Brazil, which provided access to the databases Biblioteca Virtual en Salud (BVS), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CI-NAHL), and Scopus. On the same date, the search in the PubCovid directory was performed. A digital search was conducted on January 20th, 2021, in the Web of Science (WoS) database.

The Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS) used in Portuguese were "período pós-parto," "saúde mental"; alternative terms were used for the "covid-19" descriptor, considering the nomenclature changes since the emergence of COVID-19 cases in December 2019. In Spanish, the descriptors used were "período posparto," "salud mental," and "COVID-19." In English, the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH Terms) used were "postpartum period," "mental health," "COVID-19", and "SARS-CoV-2."

According to each database's suitability, the search strategies combined DeCS and MeSH, using the Boolean operators AND and OR, as presented in Table 1. The BVS offers a specific strategy for the theme, and it was used for the search; the PubCovid database stores publications from PubMed and Embase in folders organized by subtopics; in this case, the "gynecology, obstetrics, reproduction, and pregnancy" folder was intersected with the "mental health" folder.

Table 1 Databases and search strategies used. Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil, 2021

| Database | Strategy used |

|---|---|

| BVS | ("Período Pós-Parto" OR "Postpartum Period" OR "Periodo Posparto" OR "Puerpério" OR "Period, Postpartum" OR "Postpartum" OR "Postpartum Women" OR "Puerperium" OR "Women, Postpartum" OR "Periodo Postparto" OR "Periodo de Posparto" OR "Periodo de Postparto" OR "Puérpera" OR "Puérperas" OR "Puerperal") AND ("Saúde Mental" OR "Mental Health" OR "Salud Mental" OR "Área de Saúde Mental" OR "Higiene Mental" OR "Mental Hygiene") AND (((("2019-2020" OR 2019 OR da:202*) ("New Coronavirus" OR "Novel Coronavirus" OR "Nuevo Coronavirus" OR "Novo Coronavirus" OR "Coronavirus disease" OR "Enfermedad por Coronavirus" OR "severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2")) OR ((2019-ncov) OR (ncov 2019) OR 2019ncov OR covid19 OR (covid-19) OR covid2019 OR (covid-2019) OR (covid 2019)) OR ((srag-cov-2 OR sars-cov-2 OR sars2 OR (sars 2) OR (sars cov 2) OR cov19 OR cov2019 OR coronavirus* OR "Severe Acute Respiratory Infections" OR "Severe Acute Respiratory Infection" OR "Coronavirus 2" OR "acute respiratory disease" OR mh:betacoronavirus OR mh:"Coronavirus infections" OR mh:"sars virus") AND (tw:2019 OR da:202*) AND NOT da:201*) OR (wuhan market virus) OR (virus mercado wuhan) OR "Wuhan Coronavirus" OR "Coronavirus de Wuhan") AND NOT ti:dromedar*)) |

| CINAHL | ("Período Pós-Parto" OR "Postpartum Period" OR "Periodo Posparto" OR "Puerpério" OR "Period, Postpartum" OR "Postpartum" OR "Postpartum Women" OR "Puerperium" OR "Women, Postpartum" OR "Periodo Postparto" OR "Periodo de Posparto" OR "Periodo de Postparto" OR "Puérpera" OR "Puérperas" OR "Puerperal") AND ("Saúde Mental" OR "Mental Health" OR "Salud Mental" OR "Área de Saúde Mental" OR "Higiene Mental" OR "Mental Hygiene") AND ("Wuhan coronavirus" OR "COVID19*" OR "COVID-19*" OR "COVID-2019*" OR "coronavirus disease 2019" OR "SARS-CoV-2" OR "2019-nCoV" OR "2019 novel coronavirus" OR "severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2" OR "2019 novel coronavirus infection" OR "coronavirus disease 2019" OR "coronavirus disease-19" OR "SARS-CoV-2019" OR "SARS-CoV-19"). |

| Scopus | ("Período Pós-Parto" OR "Postpartum Period" OR "Periodo Posparto" OR "Puerpério" OR "Period, Postpartum" OR "Postpartum" OR "Postpartum Women" OR "Puerperium" OR "Women, Postpartum" OR "Periodo Postparto" OR "Periodo de Posparto" OR "Periodo de Postparto" OR "Puérpera" OR "Puérperas" OR "Puerperal") AND ("Saúde Mental" OR "Mental Health" OR "Salud Mental" OR "Área de Saúde Mental" OR "Higiene Mental" OR "Mental Hygiene") AND ("Wuhan coronavirus" OR "COVID19*" OR "COVID-19*" OR "COVID-2019*" OR "coronavirus disease 2019" OR "SARS-CoV-2" OR "2019-nCoV" OR "2019 novel coronavirus" OR "severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2" OR "2019 novel coronavirus infection" OR "coronavirus disease 2019" OR "coronavirus disease-19" OR "SARS-CoV-2019" OR "SARS-CoV-19") |

| WoS | ("Período Pós-Parto" OR "Postpartum Period" OR "Periodo Posparto" OR "Puerpério" OR "Period, Postpartum" OR "Postpartum" OR "Postpartum Women" OR "Puerperium" OR "Women, Postpartum" OR "Periodo Postparto" OR "Periodo de Posparto" OR "Periodo de Postparto" OR "Puérpera" OR "Puérperas" OR "Puerperal") AND ("Saúde Mental" OR "Mental Health" OR "Salud Mental" OR "Área de Saúde Mental" OR "Higiene Mental" OR "Mental Hygiene") AND ("Wuhan coronavirus" OR "COVID19*" OR "COVID-19*" OR "COVID-2019*" OR "coronavirus disease 2019" OR "SARS-CoV-2" OR "2019-nCoV" OR "2019 novel coronavirus" OR "severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2" OR "2019 novel coronavirus infection" OR "coronavirus disease 2019" OR "coronavirus disease-19" OR "SARS-CoV-2019" OR "SARS-CoV-19") |

| PubCovid | (("COVID-19"[All Fields] OR "COVID-2019"[All Fields] OR "severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2"[Supplementary Concept] OR "severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2"[All Fields] OR "2019-nCoV"[All Fields] OR "SARS-CoV-2"[All Fields] OR "2019nCoV"[All Fields] OR (("Wuhan"[All Fields] AND ("coronavirus"[MeSH Terms] OR "coronavirus"[All Fields])) AND (2019/12[PDAT] OR 2020[PDAT]))) OR ("coronavirus"[MeSH Terms] OR "coronavirus"[All Fields]) OR ("severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2"[Supplementary Concept] OR "severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2"[All Fields] OR "sars cov 2"[All Fields])). |

Source: Own elaboration based on the research data.

The inclusion criteria set were publications between 2019 and 2020 (from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic to the date of article collection) available in full-text in Portuguese, English, and Spanish that addressed the mental health of postpartum women solely during the COVID-19 pandemic. The exclusion criteria were reflection papers, editorials, letters to the editor, experience reports, case reports, formative second opinion, videos, commentaries, research record protocols, and brief communication of results.

For the "Primary Research Characterization," which is the third step, duplicate publications were excluded using EndNoteWeb software, a free reference manager, and a practical, reliable, and transparent resource for the integrative review 20). In the sequence, titles and abstracts were read with a complete reading of the article when clarification was needed, tabulating information in an adapted instrument.

Meanwhile, the included and excluded publications were selected using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Pre-print publications were considered, which had already been published at the end of the review. Two authors reviewed this process; when necessary, the third and fourth authors analyzed the articles.

In the fourth step, "Finding Analysis," the included articles were read and reread thoroughly and critically, generating the content presented in the next section. In the second-to-last step, "Result Interpretation from Convergent Themes Emerging from the Review," the final product was discussed with the literature, describing achievements and implications. The sixth step, "Review Presentation," describes the steps for the review and the main findings of article analysis.

Since this literature review does not involve human beings, it was not submitted to the research ethics committee.

Results

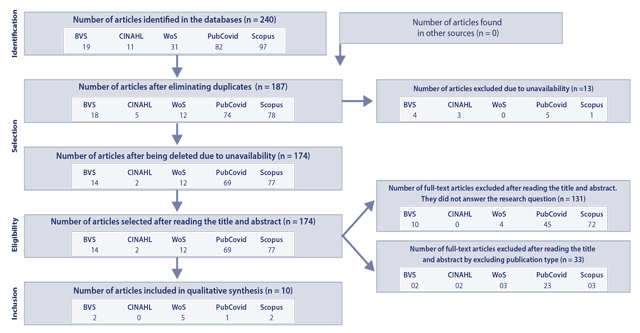

The search in the databases totaled 240 publications. Upon checking for duplicates, the authors and reference manager excluded 53 publications, and 13 others were unavailable on the Capes database. Therefore, 174 publications were reviewed, excluding 164 and including ten as the corpus for the qualitative synthesis (Figure 1) using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart 22.

Source: Own elaboration based on survey data and PRISMA adaptation 22.

Figure 1 Flowchart of the publications' search and selection. Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil, 2021

The results in Table 2 present studies conducted in the United Kingdom, the United States, China, Iran, Serbia, Turkey, Israel (n = 1 each), and Italy (n = 3). The publishing journals were mostly correlated to mental health or women's health. All those included were published in 2020 during May (n = 2), September (n = 2), October (n = 1), November (n = 3), and December (n = 2). The study types consisted of qualitative descriptive (n = 1), review (n = 1), cohort (n = 2), case-control (n = 1), quantitative descriptive (n = 1), and cross-sectional descriptive studies (n = 4). Overall, we noted that these studies aim to understand mood symptomatology, especially depressive symptoms in postpartum women during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 2 Articles included for review according to first author, country of research, journal, month and publication database, title, objective, method, results, and evidence level. Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil, 2021

| First author | Country/ Journal/ Publication month/ Database | Title | Objective | Method | Results | Evidence level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dib S 24 | United Kingdom international journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics September 2020 BVS | "Maternal mental health and coping during the COVID-19 lockdown in the UK: Data from the COVID-19 New Mum Study" | To evaluate how the mothers were feeling and dealing with the lockdown and potential ways to assist them | Descriptive analysis; online survey; participation of 1,329 women with infants under 12 months of age | More than half (71 %) of these mothers reported feeling depressed, lonely, irritable, and worried since the start of the lockdown but able to cope with the situation. Health care and contact with support groups were predictors of improved mental health while going out to work, lower family income, and the impact of the lockdown on their ability to buy food were predictors of worsening mental health. Getting out for physical activity and relaxation techniques such as meditation and yoga were potential ways of coping with the lockdown. | VI |

| Ostacoli L 25 | Italy BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth November 2020 BVS | "Psychosocial factors associated with postpartum psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study" | To investigate the prevalence of depressive and post-traumatic stress symptoms in women who gave birth during the COVID-19 pandemic and their associations with quarantine measures, obstetric factors, and relational attachment style | Cross-sectional; online survey; administration of EPDS, IES-R (Impact of Event Scale-Revised), and RQ (Relationship Questionnaire); participation of 163 postpartum women | A total of 44.2 % experienced depression symptoms, and 42.9 % experienced post-traumatic stress symptoms following childbirth. The relational attachment was avoidant-disdainful and avoidant with fear, related to the risk of depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms, respectively. The pain felt at delivery represented a risk factor for depression; the quietness at hospitalization due to the absence of visitors and the support from healthcare professionals represented a protective factor. | VI |

| Silverman ME 26 | The United States Scientific Reports December 2020 WoS | "Postpartum mood among universally screened high and low socioeconomic status patients during COVID-19 social restrictions in New York City." | To determine any changes in postpartum mood symptomatolog y among patients who gave birth before and during the COVID-19 pandemic To explore whether any differences in reported postpartum mood symptomatolog y existed between those living at high and low socioeconomic levels during these same periods | Cohort; EPDS data collection in the medical record; participation of 516 women in the postpartum period | A total of 12.4 % of the women scored above nine, suggesting depression. A statistically significant change in mood symptomatology was observed between the socioeconomic groups during the COVID-19 restrictions: women with lower socioeconomic status showed a decrease in depressive symptomatology. | IV |

| Oskovi-Kaplan ZA 27 | Turkey Psychiatric Quarterly September 2020 Scopus | "The effect of COVID-19 pandemic and social restrictions on depression rates and maternal attachment in immediate postpartum women: A preliminary study" | To evaluate the rates of postpartum depression and maternal-infant attachment status among women in the immediate postpartum period whose last trimester overlapped with the lockdowns and who gave birth in a tertiary care center that had stringent hospital restrictions due to also providing care to COVI D-19 patients in Turkey's capital | Quantitative descriptive study; administration of EPDS and MAI (Maternal Attachment Inventory); participation of 223 women in the immediate postpartum period (48 hours) | The mean EPDS score was 7 7, and 33 (14.7 %) women were identified as at risk for PPD. The mean score on the MAI was 100 26; the MAI scores of women with depression were significantly lower than those of women without depression, 73 39 vs. 101 18, respectively [p < 0,001]. It is suggested that the risk of PPD during the pandemic increased compared to pre-pandemic levels. The fact that postpartum women stay in isolated rooms and are not allowed to have any visitors may have influenced their higher EPDS scores. | VI |

| Liang P 28 | China BMC Psychiatry November 2020 WoS | "Prevalence and factors associated with postpartum depression during the COVID-19 pandemic among women in Guangzhou, China: A cross-sectional study" | To investigate the prevalence of PPD and explore the PPD-related factors among women in Guangzhou, China, during the COVID-19 pandemic | Cross-sectional study; online survey; administration of the EPDS and structured questionnaire; participation of 845 women in the postpartum period between 6 and 12 weeks | The PPD prevalence was 30 % in women within 6-12 weeks postpartum. The factors significantly related to the highest PPD scores were being an immigrant, having a sustained fever, insufficient social support, concerns regarding COVID-19 infection, preventive measures such as avoiding sharing eating utensils, and the lowest PPD scores. | VI |

| Spinola O29 | Italy Frontiers in Psychiatry November 2020 WoS | "Effects of COVID-19 epidemic lockdown on postpartum depressive symptoms in a sample of Italian mothers" | To explore the impact of COVID-19 on PPD symptoms in mothers with children under one year of age | Cross-sectional study; online survey; administration of the EPDS, the SPSS (Scale of Perceived Social Support), and the MSSS (Maternity Social Support Scale); participation of 243 women with children aged up to one year | In 44.40 %, a prevalence of PPD symptoms occurred; in 51.90 %, a substantial perception of stress was noted; 87.20 % indicated deficient maternal support; 61 % indicated that COVID-19 affected breastfeeding. Time off work and receiving financial assistance from family members were significantly associated with depression symptoms. Having been in contact with people infected with COVID-19 and fear of the baby being infected with the disease were significantly related to increased EPDS scores; women who reported no fear that their close ones were infected with the disease had higher EPDS scores. Prior abortion history and emotional issues significantly affected higher EPDS scores. Women quarantined in northern Italy had higher depression and perceived stress scores than those in central and southern Italy. | VI |

| Stonajov J 30 | Serbia international journal of Psychiatry in Medicine December 2020 WoS | "The risk for nonpsychotic postpartum mood and anxiety disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic" | To recognize the risk factors for nonpsychotic postpartum mood and anxiety disorders (NPMADs) in women during the pandemic and police lockdown in a state of emergency in Serbia | Cross-sectional study; online survey; EPDS administration; participation of 108 postpartum women with children aged under 12 months. | 14.8 % of postpartum women were at risk for nonpsychotic postpartum mood and anxiety disorders, while 85.2 % were not at risk. Women over 35 years old, single, unemployed or who became unemployed due to the pandemic, or were dissatisfied with family income scored higher on the EPDS. Quarantine, social isolation, lack of social support, and emotional issues were significantly associated with the risk of NPMADs. When comparing non-postpartum and postpartum women, postpartum women were more anxious, experienced helplessness and negative feelings, and were more worried for no real reason while in social isolation. Postpartum women estimated no need for psychological support from a professional. | VI |

| Zanardo V 31 | Italy international journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics May 2020 PubCovid | "Psychological impact of COVID519 quarantine measures in northeastern Italy on mothers in the immediate postpartum period" | To explore whether quarantine measures and hospital containment policies among women giving birth in a COVID-19 "hotspot" area in northeastern Italy increased psycho-emotional distress in the immediate postpartum period | Retrospective case-control study; administration of the EPDS in the immediate postpartum period; participation of 91 women from the study group and 101 women from the control group | The study group consisting of postpartum women during the COVID-19 pandemic (n = 91) had significantly higher EPDS values compared to the pre-pandemic control group (n = 101) (8.5 ± 4.6 vs. 6.34 ± 4.1; P < 0.001). A total of 30 % of the study group presented with an increased risk of PPD (EPDS > 12) Anhedonia, anxiety, and depression scored higher in the postpartum women study group during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the control group, with a significant difference for anhedonia. The quarantine and hospital containment measures strongly impacted postpartum women and, added to the fear of exposure to COVID-19, may worsen depressive symptoms. | IV |

| Pariente G 32 | Israel Archives of Women's Mental Health October 2020 Scopus | "Risk for probable postpartum depression among women during the COVID-19 pandemic" | To evaluate the risk of postpartum depression among women who gave birth during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the risk among women who gave birth before the COVID-19 pandemic | Cohort study on-site; EPDS administration in the immediate postpartum period; participation of 223 women. | Women who gave birth during the COVID-19 pandemic were at a lower risk of scoring high (> 10) or very high (> 13) on the EPDS compared to women who gave birth before the COVID-19 pandemic (16.7 % vs. 31.3 %, p = 0.002 and 6.8 % vs. 15.2 %, p = 0.014, for EPDS > 10 and EPDS > 13, respectively). Maternal age, ethnicity, marital status, and adverse pregnancy outcomes were independently associated with a lower risk of depression (adjusted OR 0.4, Ci = 95 % 0.23-0.70, p = 0.001 and adjusted OR 0.3, Ci = 95 % 0.15-0.74, p = 0.007 for EPDS scores > 10 and > 13, respectively). | IV |

| It was found that maternal concern exists regarding fetal radiation exposure by computerized tomography. Vertical transmission of COVID-19 is inconclusive. Early delivery of women with COVID-19 is recommended when the mother is experiencing severe symptoms; however, testing positive for COVID-19 is not the sole indicator for early delivery. | ||||||

| Sighaldeh SS 33 | Iran journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine May 2020 WoS | "Care of newborns born to mothers with COVID-19 infection; a review of existing evidence" | To discuss how to care for a newborn of a mother suspected or infected with COVID-19 from the existing evidence | Systematic review study; articles and guidelines related to COVID-19 in reproductive health, maternal, and newborn health | Late cord clamping is not indicative of an increased possibility of virus transmission, and its maintenance is recommended; early clamping is suggested if the mother presents with infection symptoms. Divergence exists regarding skin-to-skin contact, and a shared decision with the parents is essential. COVID-19 can have an insidious onset and be nonspecific in infants. The screening for COVID-19 in newborns delivered by mothers with the disease involves collecting nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, and rectal swabs within 24 hours of birth and 24 hours after the first collection, CT scanning, and epidemiologic history. Separation of the dyad if the mother tests positive for COVID-19 and no direct breastfeeding may occur due to the risk of disease transmission following delivery; isolation of the baby, and care with the milking of breast milk may occur. Separation of the mother-infant dyad and not breastfeeding may damage the mother-infant bond and increase maternal stress in the postpartum period. | V* |

*Referred to by the authors of the article as a systematic review.

Source: Own elaboration based on the research results.

Data collection was performed digitally (n = 5), on-site (n = 3), and bibliographically (n = 2). In addition to other instruments associated with data collection, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) was used (n = 8).

The evidence level was identified according to the articles' methodological characteristics and followed Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt's proposal 23:

Level I: Systematic reviews or meta-analyses of randomized controlled studies or evidence-based practice guidelines based on randomized studies or meta-analyses

Level II: Well-designed randomized clinical trials

Level III: Well-delimited controlled trials without randomization

Level IV: Well-designed case-control and cohort studies

Level V: Systematic reviews of descriptive and qualitative studies

Level VI: Descriptive or qualitative studies

Level VII: Authority opinions or expert committee reports

Level I evidence considers that the recommendations contained in these publications are highly applicable in professional practice when compared to level VI. In this review, the levels identified were IV (n = 3), V (n = 1), and VI (n = 6).

Based on the articles read, two main contents emerged: "the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of postpartum women" and "care measures for the mental health of postpartum women during the COVID-19 pandemic". Regarding "the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of postpartum women", despite the particularities of each study, this pandemic caused postpartum women to feel depressed, lonely, in an irritable mood, and worried 24, with depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms 25. Concerning the prevalence of PPD, 12.4 % presented with possible PPD 26, 14.7 % with risk for PPD 27, 30 % with a prevalence of PPD 28, 44.40 % with a prevalence of depressive symptoms, 51.90 % with perceived stress 29, and 14.8 % were at risk for nonpsychotic mood and anxiety disorders 30.

Comparing the postpartum period before and during this pandemic, postpartum women in the latter group were at 30 % higher risk for PPD 27, with higher scores also for anhedonia and anxiety 31. In the study that compared non-postpartum women to postpartum women in the pandemic, the latter presented with increased anxiety, negative feelings, and disability 30.

In this pandemic context, economic issues such as lower family income, inability to buy food 29, unemployment 29,30, financial support from family members 29 and sociodemographic issues such as being an immigrant 28, living in an area with higher infection rates 29, being over 35 years old and single 30 were pointed out as factors related to the deterioration of the mental health of postpartum women. Furthermore, low social support was associated with higher EPDS values 28,30. Other factors such as the pain experienced at delivery 25, previous abortion history 29, and previous emotional issues 29,30 posed a risk for PPD. Another study demonstrated that postpartum women were at lower risk of high EPDS scores during the pandemic 32 and that these women estimated no need for professional psychological support 30.

Themes related to worrying about exposure 31, getting COVID-19 and having a sustained fever 28, contact with people infected with COVID-19, and fear of the baby contracting the infection 29 were associated with worsening mental health. Regarding preventive measures, separation from mother and baby postpartum 33, quarantine 30,31, isolation 30, hospital isolation 31, staying in an isolated room, and not receiving visits 27 were flagged as contributors to worsening depression symptoms. From another perspective, one article pointed out that women with a higher socioeconomic status showed no changes in mood following childbirth with social containment measures and decreased depression symptomatology 26.

In "care measures for the mental health of postpartum women during the COVID-19 pandemic", caring for oneself and contact with support groups 24, quietude in hospitalization, having received support from professionals 25, and avoiding sharing eating utensils 28 were protective measures for their mental health. Going out for physical activity and relaxation techniques were means of coping with the imposed lockdown 24.

Discussion

Considering the global challenge of producing information on SARS-CoV-2 for public health, care, and research 33, it is noted that the articles included started being published in May 2020, peaking at the end of the second half (September, October, November, and December). The most significant number of publications in November indicates a possible gradation in the development of research and knowledge during the first year of the pandemic. Italy ranks as the country with the highest number of publications, possibly due to being the first epicenter of the pandemic in Europe, with numerous positive cases and deaths from COVID-19, lockdown, and quarantine on a large scale 31.

Regarding the type of research, cross-sectional studies and those that used the EPDS for data collection stand out. This instrument inquires upon postpartum depression symptomatology and, given its sensitivity in the research, supports clinical practice in the health field 34,35.

The data collection strategy used the most was the virtual collection, possibly influenced by this pandemic's implications on field research, highlighting ventures conducted remotely that innovated research in this context 36,37. In this sense, it is vital to conduct research continuously, not limiting it to emergency contexts 38, as while periods of crisis reveal challenges for research, the mission of reducing uncertainty and assisting public health remains 39.

Relative to the evidence level, Level VI contained the most significant number of studies, which indicates the development of research on this theme with other methodological designs. However, given the conditions imposed by the pandemic, it is necessary to develop alternative means of research other than face-to-face. The need for timely access to information has made it essential for the methodological research design to factor in the impositions resulting from the pandemic. Identifying the level of evidence in a review enables critical observation of the information for use in clinical practice 23. Despite the lack of symmetry in the publication of studies with well-defined methodological designs and a high level of scientific evidence that enables and subsidizes such evidence in professional nursing practice, the best evidence available is used instead of the best possible evidence. Among the publications in Brazil, systematic reviews without or with meta-analysis, protocol reviews, the synthesis of evidence studies, and the integrative review are the most adopted methodologies 40.

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of postpartum women

Epidemic events produce adverse psychological effects, such as fear of getting sick, dying, loneliness, stress, depression, sadness, irritation, and feeling of loss 41,42, leading to emotional suffering and affecting the health and well-being of individuals. It is possible to ponder the effects of the current pandemic on mental health considering the population's psychological response to previous epidemics 42,43, which can be exteriorized in emotional responses, unhealthy behaviors, and disregard towards public health guidelines 42.

The articles pointed out that depression symptoms in postpartum women may worsen in the current setting. Maternal depression is considered one of the most common mental disorders during pregnancy or postpartum 44 and affects 13 % to 19 % of pregnant women 45. In Brazil, a prevalence of 26.3 % 44 countrywide and 14 % 46 of PPD has been reported in the South of the country. Significantly greater severity of PPD symptoms is reported at the onset than before the pandemic, associating this event with increased mental health issues in the postpartum period 47. Sentiment analysis showed increased negativity 48 and a marked increase in the prevalence of self-reported significant depressive symptoms in the postpartum period compared with before the pandemic 16.

Factors that pose a risk for PPD exist. Prenatal anxiety, postpartum blues, family income, women's occupation, and pregnancy complications are mentioned as significantly relevant. High levels of stress, low social support, current or previous history of abuse, history of prenatal depression, and marital dissatisfaction issues stand out as the most common, and history of prenatal depression and current abuse as the strongest 45.

In Brazil, risk factors significant for PPD were a brown-looking skin color, low economic status, alcohol consumption, history of mental disorder, unplanned pregnancy, being multiparous, improper care during birth or for the baby born 44. In the South of the country, personal or family history of depression, sadness experienced in the third gestational trimester, being multiparous and younger were associated with a higher risk for the disease 46.

In the current pandemic, some risk factors may be increased, such as depression symptoms during pregnancy, a previous diagnosis of anxiety, perception of low social support during pregnancy, traumatic events before or during pregnancy, and harsh circumstances during pregnancy or postpartum, such as the death of a loved one, unemployment, and a high-stress load. There is a possibility of worsening symptoms due to common mental disorders (besides depression and anxiety) during pregnancy, perception of low support from the partner, marital dissatisfaction, and low socioeconomic level, added to the economic changes resulting from the pandemic 49.

Considering the known prevalence of PPD combined with changes in the postpartum period, the influence of the pandemic as a stress source 43,47, and issues such as unemployment and economic adversity, profound interference with perinatal mental health can be indicated 43. Furthermore, the measures globally adopted to decrease the transmission of SARS-CoV-2, such as quarantine, social distancing, and meeting cancellations, cause increased distress and the development of mental disorders 43 since reduced social support, social isolation, distance, and fear of being exposed or infected have consequences for maternal mental health 50.

The concern that a close person is infected increases the fear of loss, and the possible contact with someone who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 can raise the fear that the baby may be infected 29. These aspects can increase feelings of anxiety and fear in women in labor, further considering the changes in face-to-face care flows 8, whose suspension led women to feel anxious, neglected, sad, and frustrated 15. Reports state that women in the perinatal period during the pandemic experienced high suffering due to the external environment of high risk, the despair by anticipation of mourning, the limitation of family and social support, the change in interpersonal relationships, and the guilt that altered the feeling of happiness for the pregnancy 48.

In this review, anxiety and stress issues were found. A study pointed out that 12 % of participating women presented with high depression symptomatology, 60 % had moderate or severe anxiety, and 40 % felt lonely, mentioning the uncertainty regarding perinatal care, the risk of exposure of the dyad to infection, conflicting information, and the lack of a support network as key stress points 10.

During the pandemic, fathers are not allowed to visit, and newborns are isolated when tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. This isolation can harm the healthy neurodevelopment of newborns, as the presence of fathers in the postpartum stimulates the affective bond 51,52, in addition to the potential harm to the well-being and mental health of the mother 8. Evidence indicates that the uncertainty or exclusion regarding the presence of a companion and inadequate support in breastfeeding influence negatively the quality of life during the postpartum period 15.

Care measures for the mental health of postpartum women during the COVID-19 pandemic

Mental health care measures can mitigate the impact on obstetric patients 43,50. Initiatives such as teleconsultation, multidisciplinary psychological and social care support can be used 51,53.

Receiving reliable information helps reduce the implication of fake news 54 and may contribute to the non-occurrence of adverse psychological effects 28,53. In turn, watching negative news can lead to feelings of despair and helplessness 41, and lacking adequate information on the pandemic can influence the increase in fear 29,54, uncertainty 54, anxiety, depression, and other symptoms 29. Therefore, it is understood that access to reliable information is a strategy to cope with the adversities of the pandemic 41. Limiting and monitoring access to news regarding the pandemic may be beneficial 9,42,50,55.

Engaging in moderate-intensity physical exercise 9,10,41,53 for at least 150 minutes a week reduces anxiety and depression compared to women who do not exercise 11. Having family bonds, enjoying moments of reading, watching movies, and listening to music, professional assistance provided through technological resources, implementing policies to assist the vulnerable, providing essential elements for subsistence, hygiene, organization measures, meditation 9, and social support, an essential protective factor 6, are auxiliary in reducing the psychological effects of the pandemic 41. Communication through digital media 9,10,53, self-care activities 9,10, such as adequate sleep, healthy eating, emotional support from the partner staying at home, being outdoors, feelings of gratitude, and establishing routines were pointed out as sources of resilience 10.

Although the postpartum women estimate that they do not require psychological support from a professional 30, the importance of professional monitoring of mental health is emphasized 7 with guidelines on how to manage and cope with stress through the implementation and continuity of routines and social and mental health assistance 42. To identify higher-risk situations, nurses need to be aware of the relationship between the pandemic and mental health in the pregnancy-postpartum cycle 50.

Even though the COVID-19 pandemic has altered workflow in health care units and caused a high professional workload 51, the population needs to be informed of which remote assistance mechanisms to seek for mental health support since the information from reliable sources decreases fear 54,56.

When it is recorded that postpartum women had a lower risk of scoring high on the EPDS during the pandemic, the influence of support and proximity of relatives is thought to be due to stringent quarantine, a consequence of the lower spread of the virus in the region, the fact that women were not required to leave home, and that they perceived their baby to be healthy 32. Although they have not been highlighted as protective factors, these aspects should be monitored in the mental health care of this population. Other measures that assist with protection in a withdrawal period, such as having clear and compelling government information, having adequate supplies, a set quarantine period, and emphasizing the altruistic choice of quarantine, are on record 57.

In Brazil, psychological prenatal care, initially proposed by Bortoletti in 2007 58, is a form of intervention intended as psychological care, which can be provided through teleconsultation 1, for pregnant women and their partners. It preventevely aims to support them emotionally, informatively, and instructionally 59. Another resource consists of the prenatal and postpartum nursing consultation for the longitudinal follow-up, early identification of mental suffering, and the proposition of preventive, promotion, and treatment measures 60.

Conclusions

This research has identified that postpartum women feel depressed, worried, anxious, negative, and afraid. It summarizes crucial risk and prevalence information for PPD in the COVID-19 pandemic context. It has enabled the recognition of prior risk factors for postpartum mental illnesses that are not specific to the pandemic context, while factors that are unique and inherent to the pandemic, such as containment measures and risk of contracting the disease, elicit a negative effect on this population. The results also revealed that living in areas where the virus is more widespread, being an immigrant, unemployed, and lacking social support worsen mental health, particularly in vulnerable groups.

Furthermore, mental health care measures for postpartum women were identified, such as support groups, professional support, and relaxation activities that reduce mental distress.

Therefore, the importance and need for professional care for the mental health of postpartum women in all contexts are acknowledged. It becomes especially relevant in the current pandemic context, which has imposed specific conditions that can worsen mental health, considering that mood change symptoms can be harmful to the course of the entire postpartum period. In light of this, the identification of evidence on the mental health of postpartum women during the pandemic and protective measures suggest focusing on professional attention to this subject in future public health events.

The importance of studies, including national research, whose subject matter is the mental health of postpartum women is emphasized, as the postpartum period is a unique event that, although related to pregnancy, is singular in itself.