Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Universitas Psychologica

Print version ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. vol.13 no.4 Bogotá Oct./Dec. 2014

https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY13-4.ycag

"Your Clothes Aren't Going to Magically Come Off":An Exploratory Study of U.S. Latino Adolescents' Reasons for Having or Not Having First-Time Vaginal Intercourse*

"Su ropa no se quita mágicamente": Estudio exploratorio sobre las razones para tener o no tener coito vaginal por primera vez en adolescentes estadounidenses-latinos

Bernardo Useche**

Universidad Autónoma de Bucaramanga, Colombia

Gilda Medina***

Michael W. Ross****

Christine Markham

University of Texas Health Science Center Houston, United States

**School of Health Sciences, Center of Biomedical Research. E-mail: buseche@unab.ed

***Private Consultant. E-mail: E-mail: gg1104@aol.co

**** Center for Health Promotion and Prevention Research, School of Public Health. E-mails: michael.w.ross@uth.tmc.edu, christine.markham@uth.tmc.edu

Recibido: agosto 2 de 2013 | Revisado: junio 17 de 2014 | Aceptado: junio 17 de 2014

Para citar este artículo

Useche, B., Medina, G., Ross, M. W., & Markham, C. (2014). "Your clothes aren't going to magically come off": An exploratory study of U.S. Latino adolescents' reasons for having or not having first-time vaginal intercourse. Univer-sitas Psychologica, 13(4), 1409-1418. http://dx.doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY13-4.ycag

Abstract

US Latino adolescents have higher teenage birthrates and higher probabilities for early sexual initiation, compared to other racial/ethnic groups. Understanding their reasons for delaying or initiating first-time vaginal intercourse is important in designing culturally relevant health promotion programs. Using qualitative methods, we analyzed 21 semi-structured interviews with US Latino adolescents regarding their sexual initiations. Seven had sexually debuted, acknowledging sexual feelings of desire, curiosity and pleasure for their romantic partner. The remaining 14 had not debuted citing reasons of self-interest and external prohibitive factors. Eight out of 14 also attributed their status to not being in a romantic relationship. Our findings suggest several areas for increased discussion including how romantic relationships and Latino cultural values influence sexual initiation and the use of contraception. These findings could improve health promotion programs by identifying critical elements that may resonate with US Latino adolescent socio-cultural values and sexual development.

Keywords :Child & adolescent health; human sexuality; reproductive health; special populations

Resumen

Los adolescentes latinos de Estados Unidos presentan tasas de natalidad más altas y mayores probabilidades de iniciación sexual temprana en comparación con adolescentes de otros grupos raciales-étnicos. Entender las razones de los jóvenes latinos para retrasar o iniciar el coito vaginal por primera vez es importante en el diseño de programas de promoción de salud culturalmente relevantes. En el presente estudio cualitativo se realizaron 21 entrevistas semiestructuradas con adolescentes latinos sobre las razones para iniciarse o abstenerse de practicar el coito vaginal por primera vez. Siete de los participantes habían debutado sexualmente y 14 se habían abstenido de hacerlo. Quienes se habían iniciado reconocieron haberlo hecho por curiosidad, deseo sexual y por placer, pero admitieron haberse iniciado sexualmente en el contexto de una relación romántica con su pareja. Quienes se habían abstenido reportaron razones personales (no sentirse preparados, esperar hasta el matrimonio, temor de adquirir una infección sexualmente transmisible o de quedar embarazada) y también citaron fuentes externas de prohibición (padres y religión). Ocho de los 14 adolescentes también atribuyeron el haberse abstenido al no haber establecido una relación romántica todavía. El análisis de los resultados sugiere que los adolescentes latinos de los Estados Unidos con características similares a la muestra estudiada tienen los conocimientos y están dispuestos a tomar decisiones razonadas sobre su iniciación sexual.

Palabras clave :Salud de niños y adolescentes; sexualidad humana; salud reproductiva; poblaciones especiales

Introduction

Understanding the reasons for delaying or initiating first-time vaginal intercourse among US Latino youth is important in designing culturally-relevant sexual and reproductive health programs for this population expecting to comprise one-third of the nation's children ages 3 to 17 by 2036 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2004). Despite a decrease in overall adolescent birth rates, US Latino adolescents have higher birthrates than their white and African-American peers (Gilliam, Berlin, Kozloski, Hernandez, & Grundy, 2007). US Latinas are 2.8 times as likely as non-Latina whites to give birth at ages 15—19. US Latino teens in grades 9 through 12 (typically ages 14 to 18 years) who are sexually active are more likely not to use a condom during last sexual intercourse (45.1%) than their African-American and White counterparts (37.6%, 36.7%, respectively) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010). In Latin American countries such as Colombia, adolescent pregnancies are on the rise. In 1990, 13% of female Colombian teenagers aged 15-19 had become pregnant or already had a child. This percentage increased to 21% in 2005 (Asociación Probienestar de la Familia Colombiana [Profamilia], 2007) and 19.5% in 2010 (Profamilia, 2011).

In the United States, early sexual debut places Latino adolescents at increased risk for pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections (STI) and risky sexual behavior (Gilliam, et al., 2007). Latinos have a higher probability for sexual debut by their 17th birthday (69% males; 59% females) compared to their Caucasian (53% males, 58% females) and Asian (males 33%, females 28%) peers, but lower than their African American counterparts (82% males, 74% females) (Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2009).

Teenage pregnancy prevention programs have shown successes in delaying sexual initiation, reducing number of sexual partners, and increasing use of contraceptive methods. However, it remains unclear what curriculum approach (i.e. abstinence-only or comprehensive sex education programs) is the most effective (Bennett & Assefi, 2005). First—time vaginal intercourse for all teens may be influenced by factors at the individual (testosterone levels, psychological characteristics, race/ ethnicity, education, sexual attitudes and beliefs), relationship (love or closeness for a romantic partner), family (mother-daughter dyads, parental monitoring, family cohesion), and community and socioeconomic levels (Aronowitz & Agbeshie, 2012; de-Graaf, van de Schoot, Woertman, Hawk, & Meeus, 2012; Kirby, 2002; Lammers, Ireland, Resnick, & Blum, 2000; Morales-Campos, Markham, Peskin, & Fernandez, 2012; Price & Hyde, 2011; Velez-Pas-trana, Gonzalez-Rodriguez, & Borges-Hernandez, 2005). Past studies documenting the differences among US racial/ethnic minority groups and age of sexual debut have focused on risk and socio-economic factors (Auslander, Rosenthal, & Blythe, 2005; Regnerus, 2007; Upchurch, Levy-Storms, Sucoff, & Aneshensel, 1998; Vo, Song, & Halp-ern-Fisher, 2009). In contrast to their non-Latino peers, US Latinos in at least one study attributed delaying first-time vaginal sex to their religious or moral beliefs (Abma, Martinez, & Copen, 2010).

Researchers have observed that these programs assume that adolescents are unaware of the consequences of sexually risky behavior. By contrast, they contend that adolescents do possess the cognition to make decisions about their sexual behavior, including sexual initiation (Gonzaga, Turner, Kelt-ner, Campos, & Altemus, 2006; Kinsman, Romer, Furstenberg, & Schwarz, 1998; Ott, Millstein, Of-ner, & Halpern-Felsher, 2006 ) and use of safer sex methods to prevent pregnancy and STI (Gordon, 1990; Gruber & Chambers, 1987; Pestrak & Martin, 1985). Previous research finds that adolescents report psychosocial benefits from engaging in sex at the individual (fun, pleasure, sexual experience), interpersonal (increased closeness and enhancement of a relationship) and social level (increased social standing) (Cooper, Shapiro, & Powers, 1998; Kinsman et al., 1998; Undie, Crichton, & Zulu, 2007; Useche, Alzate, & Villegas, 1990; Widdice, Cornell, Liang, & Halpern-Felsher, 2006). Contending that adolescents follow a developmental continuum from abstinence to readiness to sexual activity, researchers have found that teens consider abstinence as a period when they are curious about sexual intercourse and evaluate their readiness for it (Ott & Pfeiffer, 2009).

We conducted a qualitative study to explore US Latino adolescents' reasons for having or for postponing first-time vaginal intercourse. These findings may shed light on whether US Latino adolescents are not only aware of making decisions regarding their sexual debuts, but also what salient considerations inform those decisions. These findings may provide a framework for a comprehensive research approach that includes personal motivations, socio-cultural factors and sexual development theory.

Method

Participants were recruited from an after-school teen pregnancy prevention project implemented in a large, urban high school district in Texas. The project was a comprehensive program that provided sex education, while helping participants develop sexual literacy and personal goals. Twenty-five Latino adolescents were participating in the prevention program. All parents of these 25 Latino adolescents received study program materials and forms requesting their permission for researchers to ask their children whether they would like to volunteer to participate in the study. Twenty-one adolescents (84%) received parental permission to volunteer (11 males and ten females); all agreed to participate in the study.

After completing the informed consent and a short demographic survey, participants completed an in-depth, semi-structured interview conducted in English (participant's preference) by the first author or one of two public health graduate students who were bicultural and bilingual. Conducted in September 2009, interviews were held in a private location (i.e., empty office) at the site of the prevention program. They ranged from 30 to 80 minutes and all were audio taped. Participants received $10 for completing the interview. To protect confidentiality, participant names were not used. The institutional review board at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston-School of Public Health (UTHSCH-SPH) approved the study (HSC-SPH-06-0397).

This study focuses on responses to the following question: "Approximately 50% percent of Latino high school students in the United States have had sexual intercourse and 50% have not had sex yet. If you have ever had sexual intercourse, what were the reasons? If you have never had sexual intercourse, what are the reasons for you to not have had sex yet?" This question was based on the 2007 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) that reported first-time vaginal intercourse among Latino high school students as 52% (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). Given the parity suggested by the stated percentage, we considered this question non-threatening, thereby increasing the likelihood of discussion and honest responses. Interviewers made certain that participants understood that sexual intercourse meant vaginal coitus. As a qualitative study, interviewers encouraged participants to elaborate on their responses.

Interviews were transcribed and checked for accuracy by the first author. Using Atlas.ti, V6 (ATLAS.ti, 2011), the research team used focused and reflexive coding to conduct a content analysis of responses that were organized into two exclusive analytic categories: 1.) Reasons for, and 2.) Reasons against having first-time vaginal intercourse (Char-maz, 2000; Glaser, 1992; MacQueen, McLellan, Kay, & Milstein, 1998; Morse, Barrett, Mayan, Olson, & Spiers, 2002; Srivastava & Hopwood, 2009;Whittemore, Chase, & Mandle, 2001).

Results

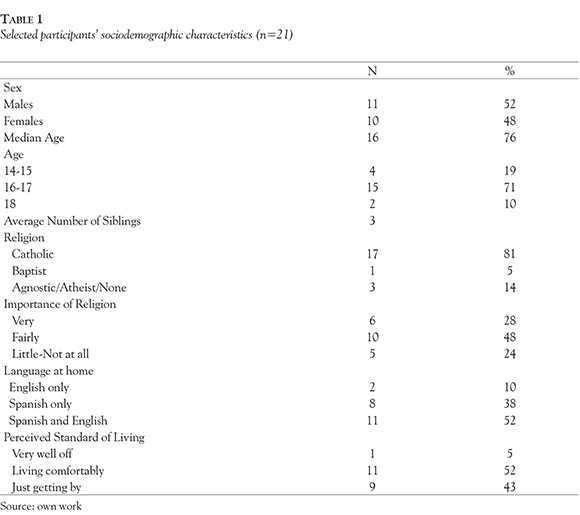

The final sample consisted of eleven males and 10 females (median age 16). Selected participants' socio demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. Additionally, based on comments provided during the interview, 15 were of Mexican origin, one was Salvadoran, one was Guatemalan, and another reported having parents from El Salvador and Puerto Rico. Three others did not state their specific Latino origins. Also based on self-report, 11 were US native-born, 7 were immigrants, three did not mention their birthplaces. All seven immigrants came to the US prior to entering the first grade.

Seven participants (30%, n = 21) had engaged in vaginal coitus, with four of the seven being male. Fourteen participants (70%, n = 21), seven males and seven females, had not engaged in first-time vaginal intercourse. With the exception of one female respondent, all respondents reported being able to control their sexual initiation. As one male respondent who had not initiated sex said, "You can stick with saying no and just not do it. You're clothes aren't going to magically come off, and you're going to start doing it." The one female respondent reported that while she was not sexually assaulted, she did feel pressure from her boyfriend to have sex.

Reasons for Having First-Time Vaginal Intercourse

Seven adolescents, four males and three females, reported having sexually debuted. Their responses were generally homogeneous and straightforward, generally acknowledging sexual feelings of desire, curiosity and pleasure but all within the context of being in a romantic relationship for a few months. Describing his relationship as "puppy love," a male participant who had dated his girlfriend for eight months said, "It wasn't like a one night stand or anything, but like we were real close, so we just like got real comfortable with each other". Although a female in this group expressed confusion over whether she loved her boyfriend, she explained feeling close to him, "I really wanted to. Not that I was curious. I guess because I thought, felt like I loved him. I do, Oh, I don't know. I don't know what love is. But right now I'm really close to him". A female respondent replied, "It was because I was curious and because I really liked that person". Reporting that sexual pleasure continued to motivate him to engage in sexual intercourse, one male respondent was proud about having had vaginal intercourse to satisfy sexual pleasure, saying, "It's just so good!" He added that his female friends could be as motivated by sexual pleasure as he was during his sexual debut, saying, "They get sexually excited and just decide to do it".

Two respondents reported other reasons for having sexually debuted. Although one male respondent acknowledged sexual curiosity while in a romantic relationship, he also reported wanting to lose his virginity. As noted previously, one female attributed her sexual initiation to pressure from her boyfriend, saying "Well, he didn't force me, but it was like a little bit of pressure". She added that she and her boyfriend had not talked previously about having sex, saying, "It just happened".

Reasons for Not Having Had First-Time Vaginal Intercourse

Seven males and seven females reported not having had vaginal sex. In contrast to the straight-forward responses from their counterparts, these adolescents had multiple and elaborate explanations reflecting both self-interest and external prohibitive factors. While most responses described reasons for postponement, one type of response suggested that some adolescents had not debuted because they were not in a romantic relationship.

Waiting for Marriage

Waiting for marriage was the most frequently mentioned reason for delaying sexual debut. Nine participants wanted to wait for marriage before having sex. For three participants marriage was part of an ideal progression that included education, career, and family. One male respondent explained, "I've wanted to get married around 25-26. Maybe-not too old but not too young and start a family when I'm 30, stabilized and everything." While these three participants apparently associated marriage with stability, four others specified that their religion prohibited premarital sex with one saying, "Because that's like the custom in our religion, so I feel like I want to wait until marriage".

Fear of Pregnancy/Parenthood and STI

Eight participants feared getting pregnant, which they automatically associated with parenthood. While most females in this group reported that they were too young to bear children and/or become mothers, males tended to voice the adverse economic and emotional consequences associated with teen parenthood. One male replied, "It's best for me because I wouldn't have to worry about that much responsibility with having a kid than just being by myself". Some added that they could better be prepared to assume parental responsibilities after securing a good job or finishing college.

Three male respondents feared contracting an STI. As a result of his sexual education courses, one male reported having a different perspective of sex: "I don't just see it as having pleasure anymore; I see it as more, like, it's dangerous because of all the STDs and all diseases that you might catch".

Interestingly, although all respondents were participating in a comprehensive after-school teen pregnancy prevention program, a few in this group doubted the effectiveness of safer sex methods. One male stated the following:

Like what if the condom broke, or the contraception doesn't work? What if like she gets pregnant, are we going to waste our lives, drop out of school?

Not Feeling Ready

Four respondents reported not feeling ready to have sex. Reporting that they were too young, they explained that the consequences of sex could disrupt their educational and career goals. A 14 year-old respondent speculated being ready at 18, an age she associated with having increased knowledge about preventing pregnancy and STI. Associating sex with adulthood, one male respondent wanted to enjoy his adolescence, an attitude supported by his parents. He recounted his parents' advice about adolescent sex in the following excerpt:

Don't do adult things and then try to go back to child things. You can't do that. For the rest of your life, if you get her pregnant and you have a kid, you just can't do it and you have to work. That's why if you're playing with adulthood, then you must be an adult. And if you're not, well, then just stay like the little kid you are.

In a relationship, he reported that both he and his girlfriend "Go out to the movies and do little kid stuff." Being the child of teenage parents and high school drop-outs, he wanted "to be somebody," and take advantage of academic and economic opportunities, concluding, "So that's the way I see it. So then why waste the chance?" Wanting to be a doctor, a female participant thought that once she had sex, she might pursue sexual pleasure and interrupt her educational plans. Saying that she did not "want to start off really early," she added, "My friends that told me after you have sex, like girls that have had sex before, it seems so easy to go do it with any other guy after that".

Family Influences

Six adolescents, three males and three females, reported that parents advised them to wait, warning of the consequences of teenage pregnancy and parenthood. Respondents also held perceptions of maternal disapproval despite the absence of discussions about sex with their mothers. College attendance of four older brothers served as a role model for a male respondent to delay sexual initiation until he was older. Although parental influences supported postponement, one male participant reported his father's encouragement for pursuing sexual pleasure, advising him not to "hold back on girls and don't take it too emotionally whenever you have sexual intercourse." His mother, however, advised him to wait until he met someone special, a recommendation he chose to follow.

Changing Convictions

Despite their convictions to wait, some respondents admitted they could change their minds. One male respondent, who wanted to wait until marriage, said the following:

Yeah. I've thought about it, too, and honestly, opportunities have come up when a girl has asked me to have sexual intercourse with her. I've been caught in the midst of the moment and everything, and I still think about it.

Two females who cited religion as a prohibiting factor acknowledged that they might still have premarital sex. As one explained, "I've been Catholic all my life and that's how I was raised —wait for marriage. But, I don't know, if it happens, it happens".

Although some respondents did not currently feel peer pressure to have sex, at least one respondent noted how peers could influence her conviction to wait. As she explained:

Because the people I hang around with are shy, so we have our own little group. Oh, if they weren't shy, I think they would, I think I would, Yes. If I really was feeling, if I had confidence and everything like that, that would lead me to different kinds of people around me. So I guess that influence would make it okay.

Not Being Involved in a Steady Romantic Relationship

The previous responses suggest respondents' choosing or feeling compelled to delay their sexual initiations. Yet, eight out of 14 (57%), all who had stated at least one reason for delaying their sexual initiation, also explained that they had not sexually debuted because they were not involved in a steady romantic relationship. They added that they wanted their first-time partner to be someone with whom they shared mutual feelings of care and desire. One female explained, "I want it to be with someone that I really care about and he really cares about me." Three adolescents in this group, two females and one male, also wanted to avoid the emotional consequences of first-time sex with a casual partner who could easily leave them to have sex with someone else.

Discussion

Adolescent US Latinos in this study voiced a range of responses explaining why they had or had not sexual debuted. Among those who had sexually debuted, responses were straight-forward and motivated by sexual desire and/or curiosity for their romantic partner. These findings may suggest that adolescents are both cognizant of and willing to act upon their sexual urges. By contrast, those who had not sexually debuted reported several reasons for their status with some respondents citing more than one reason. These reasons were not only motivated by self-interest (i.e., waiting until marriage, avoidance of teenage parenthood and STI or not feeling ready), but also influenced by external prohibitive factors (i.e., parents or religion). Our findings suggest that both groups demonstrate that they are cognizant of and willing to make decisions regarding their sexual lives.

A finding shared by both groups involves the role of romantic relationships. All who had sexually debuted and eight of the 14 (57 %,) who had not debuted reported that being in a romantic relationship was a significant factor in their sexual status. With the exception of one male respondent who noted that his desire to lose his virginity drove his sexual debut, both male and female respondents in our study associated their sexual debuts with love and sexual desire for their romantic partner. These findings are similar to a study completed in Cuba where adolescents reported their sexual debuts occurring while in romantic relationships. In that study, however, males and females differed in their reasons with males reporting sexual curiosity and females reporting being in love with their partners as reasons for their sexual debuts (Santana, Ovies, Verdeja, & Fleitas, 2006). Given that adolescent pregnancy rates are disproportionally high among Latinos in the US and rising among adolescents in Latin America, future studies comparing these two groups may shed light on the effects of acculturation on US Latinos regarding gender role expectation.

Researchers have noted that the perception of love within a serious relationship provides the social norm for accepting or delaying adolescent sexual initiation. Yet, love and its relationship with sex is problematic for adolescents who consider that love justifies sex as beautiful, instead of cheap and forbidden (Pestrak & Martin, 1985). Additionally, being in a romantic relationship may motivate adolescents to modify their rational behavioral intentions to avoid pregnancy (Rocca, Hubbard, Johnson-Hanks, Padian, & Minnis, 2010) or provide the first salient opportunity to question their sexuality (Faulkner & Mansfield, 2002). Latino cultural norms governing appropriate gender behavior may further affect sexual and contraceptive decision-making (Driscoll,Biggs, Brindis, & Yankah, 2001; Gilliam, 2007;Pulerwitz, Gortmaker, & William, 2000).

One study on US Latina adolescents in romantic relationships found that participants followed a process of accepting messages that fit their value system, rejecting messages that they felt misrepresent their beliefs, and altering messages to accept their own sexuality (Faulkner & Mansfield, 2002). Future similar studies may highlight how both male and female Latino adolescents in romantic relationship move from personal convictions to delay sexual debut to deciding to sexually debut. Additionally, interventions that build refusal skills and strengthen personal self-control might support personal convictions, attributes previously associated with sexual debut (Diiorio et al., 2001; Gilliam et al., 2007).

Some findings may reflect varying degrees of Latino cultural values. Findings regarding parental advice for delaying sexual initiation and perception of parental disapproval, despite lack of discussion may reflect cultural values of parental respect and sex talk as taboo. Interventions that teach Latino parents how to discuss important sexual topics may help avoid the adverse health effects associated with Latino adolescent risky sexual behavior. Latino cultural values of familis-mo, marianismo, and caballerismo (Allen et al., 2005; Dore & Dumois, 1990) may explain why both male and female respondents associated pregnancy with birth and parenthood despite their participation in a comprehensive sexual education program. The role and/or influence of other family members, such as siblings, may reflect the extended definition of "family" favored by Latino culture.

Our sample poses several limitations. Since respondents were volunteers in a teen pregnancy prevention program who were granted parental permission, we were unable to assess the study's representativeness to all Latino adolescents. We did not consider Latino sub-group, immigrant status, acculturation levels, or pre-coital experiences, all factors associated with sexual decision-making (Afable-Munsuz & Brindis, 2006; Gilliam et al., 2007; O'Sullivan & Brooks-Gunn, 2005; Spence & Brewster, 2010). Although our qualitative study does not aim to formulate generalizations, our sample size hindered saturation of responses, making our results exploratory and formative.

Yet, our findings suggest several areas for increased discussion and reflection, including how romantic relationships may move Latino adolescents toward sexual debuts, including the role of sexual curiosity and desire. Future qualitative research on sexual behavior decision-making may illuminate how Latino cultural values (i.e. machismo, marianismo) influence sexual initiation and the use of contraception. Extending the definition of family might also identify the circles of influence that affect Latino adolescents. These findings may enhance existing teen pregnancy prevention programs by identifying critical elements (i.e., couples, extended family, sexual desire) that may resonate with Latino adolescent socio-cultural values and sexual development.

References

Abma, J. C Martinez, J. R., & Copen, C. E. (2010). Teenagers in the United States: Sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing. National Survey of Family Growth 2006-2008 ((DHHS publication; no. (PHS) 2011-1982). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. [ Links ]

Afable-Munsuz, A., & Brindis, C. D. (2006). Acculturation and the sexual and reproductive health of Latino youth in the United States: A literature review. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 38(4), 208-219. [ Links ]

Allen, M. A., Liang, T. S., La Salvia, T., Tjugum, B., Gulakowski, R. J., & Murguia, M. (2005). Assessing the attitudes, knowledge, and awareness of HIV vaccine research among adults in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 40(5), 617-624. [ Links ]

Aronowitz, T., & Agbeshie, E. (2012). Nature of communication: Voices of 11-14 year old African-American girls and their mothers in regard to talking about sex. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 35(2), 75-89. [ Links ]

Asociación Probienestar de la Familia Colombiana. (2007). Encuesta Nacional de Demografia y Salud - ENDS 2005. Bogotá: Profamilia Colombia. Retrieved from http://www.profamilia.org.co/encuestas/Profamilia/Profamilia/images/stories/documentos/Principales_indicadores.pdf [ Links ]

Asociación Probienestar de la Familia Colombiana. (2011). Encuesta Nacional de Demografía y Salud - ENDS 2010. Bogotá: Profamilia Colombia. Retrieved from http://www.profamilia.org.co/encuestas/Profamilia/Profamilia/images/stories/documentos/Principales_indicadores.pdf [ Links ]

ATLAS.ti. (2011). Berlin: Scientific Software Development GmbH. [ Links ]

Auslander, B. A., Rosenthal, S. L., & Blythe, M. J. (2005). Sexual development and behaviors of adolescents. Pediatriac Annals, 34(10), 785-793. [ Links ]

Bennett, S. E., & Assefi, N. P. (2005). School-based teenage pregnancy prevention programs: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Adolescent Health, 36(1), 72-81. [ Links ]

Cavazos-Rehg, P. A., Krauss, M. J., Spitznagel, E. L., Schootman, M., Bucholz, K. K., Peipert, J. F., ... Beirut, L. J. (2009). Age of sexual deb ut among US adolescents. Contraception, 80(2), 158-162. [ Links ]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2008). Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 57(SS-4), 1-131. [ Links ]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2009. Morbidity Mortal Weekly Report, 59(SS-5), 1-142. [ Links ]

Charmaz, K. (2000). Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 509-535). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Cooper, M. L., Shapiro, C. M., & Powers, A. M. (1998). Motivations for sex and risky sexual behavior among adolescents and young adults: A functional perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1528-1558. [ Links ]

deGraaf, H., van de Schoot, R., Woertman, L., Hawk, S. T., & Meeus, W. (2012). Family cohesion and romantic and sexual initiation: a three wave longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(5), 583-592. [ Links ]

Diiorio, C., Dudley, W. N., Kelly, M., Soet, J. E., Mbwara, J., & Sharpe Potter, J. (2001). Social cognitive correlates of sexual experience and condom use among 13- through 15-year-old adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 29(3), 208-216. [ Links ]

Dore, M., & Dumois, A. O. (1990). Cultural differences in the meaning of adolescent pregnancy. Families in Society-the Journal of Contemporary Human Services, 71(2), 93-101. [ Links ]

Driscoll, A. K., Biggs, M. A., Brindis, C. D., & Yankah,E. (2001). Adolescent Latino reproductive health: A review of the literature. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 23(3), 255-326. [ Links ]

Faulkner, S. L., & Mansfield, P. K. (2002). Reconciling messages: The process of sexual talk for Latinas. Qualitative Health Research, 12(3), 310-328. [ Links ]

Gilliam, M. L. (2007). The role of parents and partners in the pregnancy behaviors of young Latinas. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 29(1), 50-67. [ Links ]

Gilliam, M. L., Berlin, A., Kozloski, M., Hernandez, M., & Grundy, M. (2007). Interpersonal and personal factors influencing sexual debut among Mexican-American young women in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41(5), 495-503. [ Links ]

Glaser, B. G. (1992). Basics of grounded theory analysis: Emergence vs. gorcing. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press. [ Links ]

Gonzaga, G., Turner, R. A., Keltner, D., Campos, B., & Altemus, M. (2006). Romantic love and sexual desire in close relationships. Emotion, 6(2), 163-179. [ Links ]

Gordon, D. E. (1990). Formal operational thinking: The role of cognitive-developmental processes in adolescent decision-making about pregnancy and contraception. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 60(3), 346-356. [ Links ]

Gruber, E., & Chambers, C. V. (1987). Cognitive development and adolescent contraception: Integrating theory and practice. Adolescence, 22(87), 661-670. [ Links ]

Kinsman, S. B., Romer, D., Furstenberg, F., & Schwarz, D. (1998). Early sexual initiation: The role of peer norms. Pediatrics, 102(5), 1185-1192. [ Links ]

Kirby, D. (2002). Antecedents of adolescent initiation of sex, contraceptive use, and pregnancy. American Journal of Health Behavior, 26(6), 473-485. [ Links ]

Lammers, C., Ireland, M., Resnick, M., & Blum, R. (2000). Influences on adolescents' decision to postpone onset of sexual intercourse: A surival analysis of virginity among youths aged 13 to 18 years. Journal of Adolescent Health, 26(1), 42-48. [ Links ]

MacQueen, K. M., McLellan, E., Kay, K., & Milstein, B. (1998). Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cultural Anthropology Methods, 10(2), 31-36. [ Links ]

Morales-Campos, D. Y., Markham, C., Peskin, M. F., & Fernandez, M. E. (2012). Sexual initiation, parent practices, and acculturation in Hispanic seventh graders. Journal of School Health, 82(2), 75-81. [ Links ]

Morse, J. M., Barrett, M., Mayan, M., Olson, K., & Spiers, J. (2002). Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1 (2), 13-22. [ Links ]

O'Sullivan, L. F., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2005). The timing of changes in girls' sexual cognitions and behaviors in early adolescence: A prospective, cohort study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 37(3), 211-219. [ Links ]

Ott, M. A., Millstein S. G., Ofner, S., & Halpern Felsher, B. L. (2006 ). Greater expectations: Adolescents' positive motivations for sex. Perspectives on Sexual & Reproductive Health, 38(2), 84-89. [ Links ] Ott, M. A., & Pfeiffer, E. J. (2009). That's "nasty" to curiosity: Early adolescent cognitions about sexual abstinence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 44(6), 575-581. [ Links ]

Pestrak, V. A., & Martin, D. (1985). Cognitive development and aspects of adolescent sexuality. Adolescence, 20(80), 981-987. [ Links ]

Price, M. N., & Hyde, J. S. (2011). Perceived and observed maternal relationship quality predict sexual debut by age 15. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(12 ), 1595-1606. [ Links ]

Pulerwitz, J., Gortmaker, S. L., & William, D. (2000).Measuring sexual relationship power in HIV/STD research. Sex Roles 42(7-8), 637-660. [ Links ]

Regnerus, M. D. (2007). Forbidden fruit: Sex and religion in the lives of american teenagers. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Rocca, C. H., Hubbard, A. E., Johnson-Hanks, J., Padian, N. S., & Minnis, A. M. (2010). Predictive ability and stability of adolescents' pregnancy intentions in a predominantly Latino community. Studies in Family Planning, 41(3), 179-192. [ Links ]

Santana Pérez, F., Ovies Carballo, G., Verdeja Varela, O. L., & Fleitas Ruiz, R. (2006). Características de la primera relación sexual en adolescentes escolares de Ciudad de La Habana. Revista Cubana de Salud Pública, 32(3). Retrieved from http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-34662006000300006&nrm=iso [ Links ]

Spence, N. J., & Brewster, K. L. (2010). Adolescents' sexual initiation: The interaction of race/ethnicity and immigrant status. Population Research and Policy Review, 29(3), 339-362. [ Links ]

Srivastava, P., & Hopwood, N. (2009). A practical iterative framework for qualitative data analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), 76-84. [ Links ]

Stone, V. (2002). Crude birthrates among New York City's racial/ethnic groups and Latino nationalities in 2002 (Report). New York: The Graduate Center. Available at http://web.gc.cuny.edu/lastudies/pages/latinodataprojectreports.html [ Links ]

U.S. Census Bureau. (2004). Population Projections: U.S. interim projections by age, race, and hispanic origin: 2000-2050. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/usinterimproj/ [ Links ]

Undie, C., Crichton, J., & Zulu, E. (2007). Metaphors we love by: Conceptualizations of sex among young people in Malawi. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 11(3), 221-235. [ Links ]

Upchurch, D. M., Levy-Storms, L., Sucoff, C. A., & Aneshensel, C. S. (1998). Gender and ethnic difference in the timing of first sexual intercourse. Family Planning Perspectives, 30(3), 121-127. [ Links ]

Useche, B., Alzate, H., & Villegas, M. (1990). Sexual behavior of Colombian high school students. Adolescence, 25(98), 291-304. [ Links ]

Velez-Pastrana, M. C., Gonzalez-Rodriguez, R. A., & Borges-Hernandez, A. (2005). Family functioning and early onset of sexual intercourse in Latino adolescents. Adolescence, 40(160), 777-791. [ Links ]

Vo, D. X., Song, A. V., & Halpern-Fisher, B. L. (2009). Role of race/ethnicity on adolescents' perceptions of sex-related risk and benefits. Journal of Adolescent Health, 44(Suppl. 2), S2. [ Links ]

Whittemore, R., Chase, S. K., & Mandle, C. L. (2001). Validity in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 11(4), 522-537. [ Links ]

Widdice, L., Cornell, J., Liang, W., & Halpern-Felsher, B. L. (2006). Having sex and condom use: Potential risks and benefits reported by young sexually inexperienced adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(4), 588-595. [ Links ]