Using the Theory of Planned Behavior to Explain Cycling Behavior

With the goal of lessening the environmental impact of motorized vehicles, the promotion of the bicycle as an urban travel mode has been on the rise (Ríos Flores, Taddia, Pardo & Lleras, 2015). To achieve this modal shift, modifications to city infrastructure (e.g. public bicycles, bicycle lanes) must be accompanied by cultural changes. Consequently, it is imperative to be aware of the psychological variables associated with bicycle use for commuting. One of the most widely used models to understand travel mode choice is the Theory of Planned Behavior -TPB- (Ajzen, 1991); however, the application of this theory to bicycle use limits to just a few studies conducted mainly in European cities (e.g. de Bruijn, Kremers, Singh, van den Putte & van Mechelen, 2009; Milkovic & Stambuk, 2015). The objective of this study was to evaluate the predictive power of TPB regarding bicycle use as a means of urban transportation in a Latin American city (Buenos Aires, Argentina).

Promotion of the bicycle as a travel mode

Recent decades have seen steady growth in the world's automobile fleet, as well as in the amount of traffic and road infrastructure (OICA, 2014). In Latin America, automobile use has increased by 43% from 2005 to 2014; in the specific case of Argentina, it increased by 48% (OICA, 2014). The ever more frequent use of the automobile, promoted for the advantages it offers (e.g., speed, comfort, privacy), has resulted in grave environmental and social problems, including traffic congestion and noise and air pollution (e.g., Dora, Hosking, Mudu & Fletcher, 2011; Tapia Granados, 1998).

To lessen these impacts, several cities around the world have made significant investments to prioritize non-motorized transportation modes (Ríos Flores, Taddia, Pardo & Lleras, 2015). In this respect, one of the best alternatives for urban mobility is the bicycle (Bacchieri, Barros, dos Santos & Gigante, 2010) because it not only has no negative environmental consequences, but it also has health benefits for the user (e.g. Andersen, Lawlor, Cooper, Froberg & Anderssen, 2009; de Geus, Joncheere & Meeusen, 2009; Hoevenaar-Blom, Wendel-Vos, Spijkerman, Kromhout & Verschuren, 2011). Various urban centers around the world have implemented public policies to promote its use -e.g., the construction of bicycle lanes, public bicycle rental stations- (Pucher & Buehler, 2008). In the past decade, the number of cities with a bicycle-sharing system grew from 13 in 2004 to 855 in 2014 (Fishman, 2015). Nonetheless, changes in infrastructure are not enough to modify mobility behaviors (Moudon et al., 2005; Parkin, Wardman & Page, 2008). Changes in the beliefs and attitudes of citizens are also required. Baumann, Bojacá, Rambeau, and Wanner (2013) point out that although several Latin American cities have developed adequate infrastructure for bicycle use, the percentage of persons that actually take advantage of it remains low. The authors suggest this may be due to negative attitudes to-wards this transportation mode, associated with low socio-economic status and higher safety risk.

As Heinen, Maat and van Wee (2011) indicate, the individual decision to use an automobile over some other transportation modes is a potential starting point for interventions aimed at changing mobility behavior. When deciding among different transportation modes, subjects weigh their beliefs and attitudes towards each. For this reason and to achieve a cultural change in sustainable mobility, it is essential to know the psychological factors influencing bicycle commuting.

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) in explaining bicycle use

TPB (Ajzen, 1991) is one of the most widely used psychological models to study travel mode choice (for a review see Gardner & Abraham, 2008; Jakovcevic, Franco, Caballero & Ledesma, 2015). This theory maintains that people make reasoned choices and opt for those alternatives that guarantee the most benefits with the least costs (e.g., in terms of effort, money, safety and social acceptability). According to TPB, three principal factors guide human action: a favorable or unfavorable attitude towards the behavior; a perceived social pressure to engage in the behavior or subjective norm, and the perception of control over it (perceived behavioral control). Collectively, these three considerations generate a behavioral intention, which is the immediate antecedent to the behavior object of the explanation (Ajzen, 2002). As a general rule, the more favorable the attitude, the stronger the subjective norm and the bigger the perceived behavioral control towards a behavior, the stronger it is the intention to behave in that manner (Ajzen, 2002). From this theoretical perspective, the intention to use a bicycle directly determines its use. To generate this intention, a person must have a positive attitude toward bicycle use, perceive that others also regard it as appropriate, and consider himself/ herself capable of using a bicycle.

Table 1 summarizes previous studies that applied the TPB to the understanding of cycling behavior (Forward, 2004; de Bruijn et al., 2009; Heinen et al., 2011; Milkovic & Stambuk, 2015; Frater, Kuijer, & Kingham, 2017; Acheampong, 2017). In general, the TPB model explains, to a large extent, the behavioral intention and the behavior (explained variance from 25% to 73%). Furthermore, when other psychological variables are included (e.g. habit, personal norm), there is no observable significant increase in explained variance (Frater et al., 2017; Milkovic & Stambuk, 2015; de Bruijn et al., 2009). In terms of the relative importance of the model's various components, the results varied. Only one study found significant effects for all of the model's components (Milkovic & Stambuk, 2015). In other studies, perceived behavioral control seemed to be the component most consistently associated with behavior (Acheampong, 2017; Heinen et al., 2011; de Bruijn et al., 2009; Forward, 2004). Three of the seven studies found attitudes to be associated, and one of these found them to be the most important (Milkovic & Stambuk, 2015). Lastly, regarding the subjective norm, two studies identified it as a predictor, and it emerged as the most important in one about secondary school students (Frater et al., 2017). In any case, it is difficult to compare results across studies due to differences in methodology, the criteria being predicted (behavioral intention or the behavior itself) and the statistical focus used to evaluate the model (with all the variables placed at the same level or according to those levels proposed by the TPB).

Additionally, there have been studies to identify the promoting and inhibiting factors on the use of the bicycle as a means of stimulating physical activity (see Caballero et al., 2014). These studies indicate that the main promoters include social facilitators (e.g., social support, modeling; de Geus et al., 2008; Titze et al., 2007, 2008), as well as the perceived feeling that one is trained to use a bicycle (Nkurunziza et al., 2012; Titze et al., 2007). These variables could be indicators of the subjective norm as well as the perceived behavioral control postulated by the TPB. Lastly, there is other evidence indicating that attitudes towards the bicycle are related to its efficient use (Emond, & Handy, 2012; Hunecke et al., 2010; Rondinella et al., 2012).

Collectively, the reviewed antecedents suggest that TPB is a suitable theoretical approach to ex-plain bicycle use behavior. However, the previous research was conducted mainly in European cities, where contextual barriers (distance, infrastructure, etc.) to bicycle use are assumed to be lower than in Latin American cities. Additionally, the results vary widely, suggesting that cultural and contextual variables might be relevant. The present study aims to evaluate TPB according to the guidelines proposed by Ajzen (2002) in explaining the se-lection of the bicycle as a means of commuting to university in an Argentine city (City of Buenos Aires). In particular, the study analyzes the contribution of the TPB and the relative weight of each of its components in predicting bicycle use to commute to university. Based on the findings of prior studies, we hypothesize that the model will predict not only behavioral intention but also the final behavior. We hope that this study will shed light on the usefulness of the TPB in attaining a greater understanding of bicycle use.

Method

Participants

The sample comprised was of 172 participants (69% women) from the Psychology Department of the University of Buenos Aires (ÜBA). The average age was 25.85 years (SD = 8.7). In terms of their roles in the university, 92% were undergraduate students and 8% employees. The preponderance of female participants matches the population values reported in the last university census for this department (UBA, 2011). Regarding the transportation mode used to commute to the university, 60% indicated using public transportation, 27% a bicycle, 7% a private motorized vehicle (automobile or motorcycle), and 6% walked to the university. The vast majority (97%) of participants indicated they knew how to ride a bicycle, 58% reported having access to one sometime or always, while 42% indicated never having access. Among them, 55.2% said they had access to a car sometime or always, and 46.5% had a driver's license. We should note that Buenos Aires city has a free public bicycle system; thus any citizen can have access to a bicycle. As an inclusion criterion, subjects were required to be city residents to control distance as a factor that could affect the selection of the bicycle for the trip to the university. The commuting distances to the university ranged from 1.6 km to 25.9 km and averaged 6.34 km (SD = 3.86).

Procedure

An instrument was developed based on the TPB. We evaluated the initial version with a sample of 10 participants, who responded to and discussed it in an interview. Based on these interviews, we made changes and improvements to instructions and the items. The corrected version of the instrument was administered to the total sample, using a casual non-probabilistic sampling. Participants were contacted at the university as well as via an email sent to a group of students. These individuals were invited to participate in a study on attitudes towards different travel modes. Prior to responding, we asked them for their informed consent and guaranteed confidentiality, anonymity and the right to stop participating whenever they wished to. Of the total number of subjects in the sample 18% (n=31) responded to the survey online and 82% (n = 141) did so in person. We did not find any significant differences between these groups (online vs. in person) in their TPB measures.

Variables and Measures

Attitudes Towards Bicycle Use (ATT)

These were evaluated using a semantic differential scale developed by Caballero et al. (2015) and based on research by de Brujin et al. (2009) and Mann and Abraham (2012). Participants indicated to what extent (from 1 to 7) they felt commuting to university by bicycle was: good/bad, uncomfortable/comfortable, prejudicial/beneficial, un-pleasant/pleasant (M = 5.55; SD = 1.68; α =.90).

Subjective Norm and Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC)

These were evaluated using items pertaining to bicycle use adapted from Mann and Abraham (2012) and TPB, based on the guidelines established by Ajzen (2002). The subjective norm was evaluated based on the degree of agreement with three items (e.g. "My friends feel that I should use a bicycle for most of my trips to the university next week") while PBC was examined based on the degree of agreement with four items (e.g., "I feel I am capable of using a bicycle for most of my trips to the university next week"). In both instances, a 7-point scale was used from 1 (disagree) to 7 (agree). Both subjective norm (M = 3.40; SD = 1.58) and PBC (M = 4.66; SD = 1.95) displayed good internal consistency (α = .86 y α = .83, respectively).

Behavioral Intention

This factor was evaluated based on the degree of agreement with four items (e.g., "Intend to use a bicycle for most of my trips to the university next week") that were constructed based on suggestions by de Brujin et al. (2009) and Gardner (2009). Participants responded using a scale from 1 (dis-agree) to 7 (agree; M= 3.52; SD = 2.36; α =.96).

Bicycle use Behavior

The transportation mode used to commute to the university was evaluated based on two questions: (a) the number of trips to the university made during the week prior to being administered the survey and (b) transportation mode used for each of those trips. Based on these responses, the per-centage of trips made by bicycle was calculated taking the number of them made using this travel mode divided by their total to the university made during the previous week.

Given that this measure evaluates past bicycle use behavior, it was re-evaluated with a sub-sample of participants (n = 39) a week after we administered the complete survey. This sub-sample (aver-age age: 23.5 years, SD = 7.23; 74 % women) did not show significant differences in terms of sex and age with the overall sample (p >.05). We will refer to the behavior evaluated in the first step as Past behavior and to the one in the second step as Present behavior. According to Bamberg, Ajzen and Schmidt (2003), a strong correlation between past behavior and present behavior would indicate stability in mobility behavior over time.

Data analysis

An exploratory analysis of the data was con-ducted to evaluate missing values and detect extreme cases. None of the items had more than 5% missing data, and we randomly distributed them. As a result, we decided to impute missing values via the expectation-maximization method. We analyzed the existence of univariate atypical cases via standard score calculations; those with z scores greater than ± 3.29 were considered atypical (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). From a final examined sample of171 cases, only a single case showed univariate atypicality. We also discarded the presence of multivariate atypical cases via a Mahalanobis distance test (p < .001).

Secondly, we conducted a bivariate correlation analysis for validating past bicycle use behavior as a criterion variable, analyzing the association between it and present behavior. Lastly, we per-formed a path analysis to evaluate the TPB'S fit statistic to the empirical data (Kline, 2011; Wolfle, 2003). For the analysis of symmetry and kurtosis, we considered the values between +1.00 and -1.00 as excellent, while those inferior to 1.60 as adequate (George & Mallery, 2001). For the multivariate normality analysis, Bollen's (1989) criterion was used, which holds that whenever the value of p (p+2), where p is the number of observed variables, is greater than Mardia's co-efficient, then this assumption can be considered met. Additionally, as Rodríguez Ayán and Ruiz (2008) indicate, Mardia's multivariate index values inferior to 70 show that the departure from multi-variate normality is not a critical problem for the analysis. In terms of multicollinearity, Pearson's r correlations were analyzed, with the criterion that values equal to or greater than .85 indicate multivariate collinearity (Kline, 2011). Lastly, the model's parameters were estimated using the ML method (Maximum Likelihood). Several indices were calculated to evaluate the model fit: chi square/degree of freedom ratio (CMIN/DF); comparative fit index (CFI); Goodness-of-fit index (GFI); Adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI); normed fit index (NFI); root-mean-square residual (RMSR), and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) (Hu & Bentler, 1995). Acceptable values for the fit indexes were: CMIN/DF below 5; CFI, GFI, AGFI, and NFI above .90; RMSEA below .06, and RMSR below .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). We used the EOS 6.1 software (Bentler, 1985).

Results

Descriptive statistics

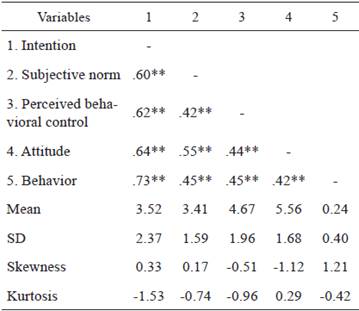

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, skewness, kurtosis, and bivariate correlations for each variable. In general, we observed that asymmetry and kurtosis indexes were adequate (George, & Mallery, 2001), supporting the existence of univariate normality. Further, Mardia's coefficient was -.94, which, according to Bollen (1989), indicates the presence of multivariate normality, as it is inferior to p (p+2) = 14.

Table 2 Descriptive statistics of variables of TPB model regarding bicycle use behavior to commute to the university.

Note:

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

The analyses of correlations between TPB variables do not indicate the presence of multivariate collinearity, given that the values of the first were inferior to .85 (Kline, 2011). Table 1 shows moderate, positive and significant correlations between TPB variables and bicycle use behavior, and indicates that the strongest correlation exists with behavioral intention. Additionally, we observed positive, significant and moderate correlations between the remaining variables.

Path analysis

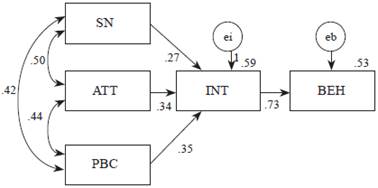

Figure 1 shows the TPB model and the estimated parameters. The model displayed an excellent fit (GFI = 0.997; AGFI= 0.984; CFI = 1.000; NFI = 0.997; CMIN/DF = 0.478; RMSEA = 0.001; RMSR = 0.011). The intention to use a bicycle explained 53% of bicycle use behavior and the variables subjective norm, perceived behavioral control and attitude explained 59% of intention variance. The variables subjective norm (β = .27; p < .001), attitude (β = .34; p < .001) and perceived behavioral control (β = .35; p < .001) have a direct positive and significant effect on intention. In turn, intention directly predicts, in a positive and significant way, the use of a bicycle to commute to the university (β = .73; p < .001).

Note: SN: subjective norm; ATT: attitudes towards bicycle use; PBC = perceived behavioral control; INT= behavioral intention; BEH: bicycle use behavior. X 2 (df) = 1.33 (3), p > .05, GFI = 0.997; AGFI= 0.984; CFI = 1.000; NFI = 0.997; CMIN/DF = 0.478; RMSEA = 0.000; RMSR = 0.011.

Figure 1 Path diagram for TPB model: bicycle use behavior to commute to the university showing standardized path coefficients and correlation ratios (N =171).

Discussion

The goal of this study was to evaluate the value of TBP to explain bicycle use as a travel mode to commute to the university. In summary, the results indicate that it is an appropriate model to explain this behavior. In fact, 53% of the variance in bicycle use behavior was explained solely by behavioral intention. Further, 59% of behavioral intention was explained by its predictors: attitude towards the bicycle; subjective norm, and perceived behavior-al control. The results are very much in line with previous studies that indicate the usefulness of the TPB in explaining bicycle use (Forward, 2004; de Bruijn et al., 2009; Heinen et al., 2011; Milkovic & Stambuk, 2015; Frater, Kuijer, & Kingham, 2017; Acheampong, 2017). Our results coincide especially with those of Milkovic and Stambuk (2015), who found that the model's three components explained behavioral intention with attitudes and perceived behavioral control being stronger predictors than the subjective norm. We understand that the similarity between our study and theirs is due to the same behavior criteria (commuting to university), while others were conducted in different settings and involved other trip destinations. In a more general sense, our findings are also in line with studies that indicate the usefulness of the TPB in predicting travel and mode choice behavior for conveyance means other than the bicycle, such as the automobile (Abrahamse et al., 2009; Bamberg & Schmidt, 2003; Gardner & Abraham, 2010; Kaiser & Gutsche, 2003; Klöckner & Blöbaum, 2010) and public transportation (Thøgersen, 2006).

We should note that, as far as the authors are aware, this is the first study that uses a non-European sample. As indicated in a review of the literature on the influence of psychological factors on bicycle use (Caballero et al., 2014), the vast majority of studies in this area have taken place in Europe, where bicycle use is more common and infrastructure conditions are more favorable. Conversely, in Latin America, policies promoting bicycle use are relatively recent, and personal fac-tors play an essential role in the selection of this transportation mode.

The present study had some limitations worth mentioning. First, given that we used an incidental sample comprised mainly of university students, the results cannot be extrapolated to the general population. Complementary studies on other populational groups are needed. Second, bicycle use behavior was evaluated using a self-reporting instrument, which implies the possibility of response bias (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1995). However, un-like previous studies (de Brujin et al., 2009), the stability of mobility behavior was examined at two different moments in time. This shows that the model predicts not only past but also future behavior, just like Ajzen (1991) suggested.

It is the belief of the authors that the results of this study reinforce TPB'S applicability in the exploration of transportation mode choice and offers some guidance for promoting bicycle use. First, the evaluations of bicycle use (attitudes) showed their link to the intention of use. It is essential, therefore, to reinforce these attitudes through, for example, communication campaigns that as-sociate bicycle use with enjoyment, freedom and time savings. In addition to that, it is crucial to develop the perception among individuals that this is an activity they are capable of doing. In this respect, actions to increase or reinforce perceived behavioral control are imperative. Possible interventions include raising awareness of bicycle use as an accessible activity and offering training pro-grams or coaching to teach people to ride a bicycle in an urban environment. Lastly, beliefs of what others think (subjective norm) about bicycle use also play a central role. These beliefs can change via the promotion of social bicycle use activities, such as group rides or massive bicycling events that consolidate bicycle use as a social activity. It would be interesting for future research to take steps to evaluate the effectiveness of some of these measures.