Introducción

The migratory phenomena have been present in the history of Brazil since its beginnings, primarily due to the colonization policies that brought Europeans and Africans to populate the country (Figueredo & Zanelatto, 2017). Brazil has been opened to a new flow of immigrants and refugees.

Data from official governmental agencies show that from 2011 to 2019, 1,085,673 migrants were registered, including all legal protections (Observatório das Migrações Internacionais [OBMigra], 2020). Among these migrants, around 660,000 were Latin Americans with a long-term staying projection—more than one year of residence in the new country. This number could be even higher, although the strike of the Covid-19 pandemic implied several difficulties for the mobility processes, mainly because of the closure of the international borders, which resulted in a significant drop in the number of immigrants and asylum requests in 2020 (United Nations Refugee Agency [UNHCR], 2021).

According to the official data, Brazil’s second highest number of immigrants or asylum seekers is the Haitian community, accounting for around 100,000 people until 2018 (Cavalcanti et al., 2020). Haiti is located in the Caribbean, with an estimated population of 10.32 million, which has been struck by three major natural disasters—an earthquake in 2010 and hurricanes in 2016 and 2020— factors that have contributed to this migratory movement, known as the Haitian Diaspora (Joseph & Neiburg, 2020). Cogo (2014) proposes that poverty and natural disaster are fundamental, though not absolute, factors in this massive migratory shift. Pre-migratory relations between Brazil and Haiti are closely related to the current migratory activity and policies. Emotional and symbolic bonds established during the Brazilian humanitarian mission in Haiti also made Brazil a destination among immigrants (Cogo, 2014). In addition, Brazil was seen as a welcoming country since it has an expressive proportion of Afro-descendants and many workand studyopportunities. At the time, the country was also in a favorable historical context because the nation was chosen to host the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics (Mejía & Cazarotto, 2017). Furthermore, the Haitian’ migratory process to Brazil was stimulated by the opening of Brazil’s borders in 2010, in contrast to the restrictive migration policies of the United States or European countries at the time (Meroné & Castillo, 2020).

When Haitian immigrants crossed Brazilian borders, they usually claimed the status of refugee, mainly due to precarious living and sustenance conditions in Haiti after the natural disasters. However, this prerogative did not meet the Brazilian immigration legislation established at the time, the “Foreigners Act” (1980) and the “Refugee Act” (1997) (Yamamoto & Oliveira, 2020). As an immediate response, Brazil began to accept the entry of Haitian immigrants based on a humanitarian visa, which only applied to those with no criminal record (Mejía & Cazarotto, 2017). This particular visa allowed immigrants to request the necessary documents to enter the labor market in the country formally. This means Brazil did not have specific laws to deal with migration flows until recently. It was only in 2017 that the “Migration Act” was instituted, which removed the conception from the law that immigrants are a threat to national security and established several rights and duties to any migration context (Zanatti et al., 2018). The law establishments include guaranteeing equal conditions to nationals regarding the right to freedom, security, and access to public health and education services. However, hosting and its specific necessities may be disregarded by this law and public policies. Bourhis et al. (2010) showed that different policies that go further than state levels should be adopted, providing local, community, and institutional actions.

Among the psychosocial characteristics, the processes of acculturation have gained weight, mainly due to the relation to predictive factors of mental health and quality of life (Sam & Berry, 2010). Acculturation is the engagement of immigrants in another cultural context. It can be perceived in the changes that occur when individuals and groups from different cultures come into contact with other people’s cultural and national contexts, wherein they have to reorganize their lives (Sam & Berry, 2010). Since the 1960s, many definitions have been proposed to explain these cultural contact processes better. In the Psychology field, acculturation as a concept becomes internationally known through Gordon (1964), from an assimilationist and individualizing perspective, which sees the process as the acquisition of the dominant culture by immigrants.

Since this model the most popular one is the Interactive Acculturation Model (IAM), developed by Bourhis et al. (1997), which permits the analysis of acculturation phenomena both from the perspective of immigrants and the communities they settle. The host community can adopt five acculturative orientations for immigrants: integration, when the community wishes the immigrants to adopt elements of the new culture while they maintain some aspects from their cultures of origin; assimilation, when the desire is for immigrants to adopt the new culture, abdicating their cultures of origin; segregation, when the community wants the immigrants to live according to their cultures of origin, without adopting elements from the new culture; exclusion, when immigrants are not expected to be part of any culture, they should abdicate their cultures of origin and not adopt any elements of the new culture; and individualism, when the community sees the immigrants as individual people, without considering aspects of their cultural origins. Lastly, Montreuil and Bouhris (2004) complemented the model with the orientation of transformation, which deals with the host community accepting specific changes in its context to ’adapt the immigrant’s culture better.

In terms of chosen regions by the Haitian immigrants, considering that Brazil is a country of continental size, the southernmost states (Rio Grande do Sul, Paraná, Santa Catarina, and São Paulo) are the leading destinations (Zamberlam et al., 2014). However, there are still very few studies about the new inhabitants within this context. Among these, a survey was conducted with 96 Haitian immigrants in 2014. Participants were male and living in Rio Grande do Sul, outlining the sociodemographic profile of this population. The majority, aged between 25 and 34, married or in a stable union, arrived in Brazil in 2010. Most had left children in Haiti, had a complete or incomplete high school education, spoke Creole and/or French, were religious, and sent money back to their families. In addition, studies were conducted on employment insertion, identifying that most of these immigrants were employed in the food, furniture, civil construction industries, and other fields. In some cases, they have been unemployed since arriving in Brazil (Zamberlam et al., 2014). This information provides an overview of this immigration, though more expansive studies are still required, especially those that include Haitian women and children, as there is still no official data about these groups.

Regarding phenotypic characteristics, the Haitian population is mainly black (95%; Central Intelligence Agency [CIA], 2014). According to the Brazilian Demographic Census of 2010 (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [IBGE], 2010), even though 50.7% of the Brazilian population self-describes itself as black or mixed race, the State of Rio Grande do Sul, colonized chiefly by Germans and Italians, has the second lowest population of self-described black or mixed race (16.2%) people, followed by Santa Catarina (15.3%). Hypothetically, this may be seen as a factor that contributes to how racism is manifested in the State of Rio Grande do Sul. One factor that plays a role in assuming acculturative orientations by the host community is prejudice, with racial discrimination standing out in this case (Bourhis et al., 2010; Rojas et al., 2014; Wagner et al., 2013).

In addition, Brazil is structured on a racist model, a legacy of the country’s history of colonization and enslavement of indigenous and black people. This structural racism still integrates the functioning and organization of the political and socioeconomic dimensions of society, which reproduces several inequalities and violence against racialized people (Almeida, 2018). When international immigrants arrive in the country, they are also racialized and welcomed in different ways, according to their ethnic-racial social marker (Oliveira, 2019). Even though racism is easily observed in social disparities, the way it is individually or collectively expressed nowadays is no longer as explicit as in the past. It is gradually being replaced with a more subtle and “politically correct” form of discrimination, which is referred to as modern racism (Santos et al., 2006). According to the same authors, this type of racial prejudice is present in two dimensions related to the denial of the existence of racism and the affirmation of differences between white and black populations.

In a study by Rojas et al. (2014), in Spain, immigrants who suffered greater prejudice tended to reject the new culture more, while immigrants who reported having suffered less prejudice sought to integrate more cultural elements from this new context. In turn, individuals from the host community who show greater prejudice also tend to be more assimilationist concerning immigrants. This attitude may be because these host community members believe that the immigrants are obliged to adopt the customs of the context of which they are now part. Therefore, trying to convert immigrants into people more similar to local inhabitants will reduce the perception of immigrants as being threats.

In another study conducted in Quebec, encompassing Haitian, French, Latino, Asian, and Jewish immigrants (without specifying nationalities), results showed that the local population saw Haitian immigrants as the least hard-working, punctual, honest, and intelligent while also seen as more aggressive and violent than the others (Tchoryk-Pelletier, 1989). Starting with these stereotypes, Montreuil and Bourhis (2001) conducted a study with the Canadian host population, monitoring acculturative orientations regarding Haitian and French immigrants in Quebec. The results showed that the host community adopts orientations of individualism and integration regarding immigrants. These orientations tend to be more prominent concerning French immigrants while showing themselves as less segregationist, assimilationist, and exclusionist with French immigrants than with Haitian immigrants (Montreuil & Bourhis, 2001). Lastly, a study in Germany has revealed a higher expectation by the host community that the children of immigrants from “devalued” groups adopt an assimilationist approach. As such, parents are permitted to maintain their cultures of origin, though their children should assimilate more elements from the new cultural context (Kunst & Sam, 2014). These findings corroborate the IAM’s presumptions since they indicate acculturative orientations sensitive to the group to which the immigrants belong. As such, certain groups are considered “valued” while others are “devalued” (Montreuil & Bourhis, 2001).

Regarding specifically the Haitians’ point of view, a study sought to access the perception of 67 of these immigrants about their psychosocial aspects: access to public policies and social support, sociodemographic and socioeconomic profile, acculturative orientations, prejudice, and quality of life in Brazil (Weber et al., 2019). Participants were aged between 19 and 58 years, mostly men (77%), and also residents of an interior city. Results suggested that immigrants adopted the acculturative orientation of integration while living in this Brazilian community. However, segregation was the second acculturation orientation most scored, indicating ambivalence toward immigrants, since this result is opposite to the highest outcome, integration orientation. The study stated that Haitian immigrants mostly tended to integrate into the community since they have a better quality of life and perceive less prejudice when compared to Haitian immigrants hosted in France and the United States. However, the authors also suggest caution when interpreting the results since the time of migratory mobility in Brazil was shorter than in these other countries.

The IAM’s authors noted that the acculturative orientations adopted by the host community influence and are influenced by the ’State’s social policies (Bourhis et al., 2010; Wagner et al., 2013), which may either facilitate or complicate ’immigrants’ interaction with the host community in terms of the acculturation process. Countries with intense migratory flows, such as France and the United States, have mainly adopted assimilationist public policies (Montreuil & Bourhis, 2001; Wagner et al., 2013). However, there is a consensus that integrationist policies result in reduced acculturationrelated stress and better psychological and socio-cultural adaptation of immigrants.

Studying the perception of a Brazilian community that receives a large number of Haitian immigrants in a short period provokes changes and reactions that may be beneficial to the migratory process of these immigrants and the community that hosts them (Bourhis et al., 2010). It is also important to investigate about immigration, racism, and discrimination in contexts other than state capitals or large urban cities since Brazilian Migration Policies are prioritizing strategies to interiorize and host immigrants in countryside cities, where they could have more economic opportunities (UNHCR, 2021). The most recent example is the “Operação Acolhida” (Shelter Operation), a governmental task force developed to support the increased number of Venezuelans seeking refuge in Brazil. The Brazilian National Armed Forces support the task force, which aims to welcome, shelter, and interiorize Venezuelan immigrants to small and medium-sized cities in Brazil, where industrial or fridge companies are seeking cheap labor (Silva et al., 2021). Even though the policy was based on the distorted conservative narrative of “saving people from communism,” the operation has already interiorized over 56 thousand Venezuelans to more than 670 Brazilian cities (UNHCR, 2021).

However, this policy seems to support Venezuelans, not embracing other nationalities of immigrants seeking refuge in the country.

Accordingly, addressing how a host community perceives the arrival of a new group of immigrants in the south of Brazil may shed light on the community relationships among them, as immediate interpersonal relationships are established within these communities. This study addressed this issue since we aimed to identify the acculturative orientations adopted by a host community concerning Haitian immigrants in the countryside of Brazil and the influence of sociodemographic variables and racial prejudice. We hypothesized that (a) older age and higher income would predict higher racial prejudice outcomes and a higher tendency to adopt segregation/exclusion acculturation orientation; (b) higher racial prejudice outcomes would also be associated with a higher tendency to adopt segregation/exclusion acculturation orientation.

Furthermore, as far as we know, no studies have investigated the relationship between quality of life and acculturation orientations in host communities. Thus, we also aimed to explore these possible associations in the targeted population. Regarding this objective, we hypothesized that worse quality of life outcomes would predict a higher tendency to adopt segregation/exclusion acculturation orientation.

Method and instruments/materials

Participants

This study includes the participation of 88 Brazilian inhabitants from a city in the countryside of Rio Grande do Sul. The sample was predominantly women (62.5%), aged between 18 and 72 years old, while the average age and years of study for all participants were, respectively, 33.63 years (SD = 13.82) and 12.69 years (SD = 4.06). The study sample was convenient and representative (90% degree of confidence, sample error of 10%).

The city was selected for hosting the largest number of Haitian immigrants (3%) in the region. Sample criteria employed data from the most recent census by the IBGE (2010), which, on the date of data collection initiation, stated a city population of 20,514 inhabitants, with a high Municipal Human Development Index (.076), primarily white population (89.6%), and a low unemployment rate (3.6%), when compared to the national index (11.6%).

Materials

Sociodemographic Data Questionnaire. A sample profile was generated considering age, gender, education level, profession, employment, income, marital status, and socioeconomic class.

Host Community Acculturation Scale (HCAS) (Bourhis & Montreuil, 2013). An instrument that assesses the six acculturative orientations—integration, assimilation, segregation, exclusion, individualism, and transformation—of the host community members relative to a specific group of immigrants. This is a self-applicable, seven-point Likert-type scale. The domains included were Culture, Values, Customs, Endogamy/Exogamy, and Employment, which resulted in an instrument comprising 30 items. The instrument was translated into Portuguese and adapted to the Brazilian context based on the original instrument in French (Montreuil & Bourhis, 2001); it had adequate internal consistency (0.74). Other studies from countries such as France, Canada, and Italy have confirmed its validity (Montreuil & Bourhis, 2004; Trifiletti et al., 2007; Weber et al., 2019).

Modern Racism Scale (Santos et al., 2006). The Modern Racism Scale, validated and adapted to the Brazilian context by Santos et al. (2006), measured the cognitive components of subtle racial attitudes. The Likert-type scale of 7 points features 14 items and comprises two factors: Denial of Prejudice and Affirmation of Differences. Its internal consistency was adequate (0.74) and was validated by Santos et al. (2006).

World Health Organization Quality of Life BREF (WHOQOL – BREF). The WHOQOL is an instrument to assess quality of life as a subjective construct. The abbreviated version (BREF) comprises 26 questions with the best psychometric performance extracted from the original version (WHOQOL100). The instrument comprishases four domains: physical, psychological, social relations, and environment. The version used in Portuguese showed adequate internal consistency (between 0.69 and 0.84) and was validated in Brazil by Fleck et al. (2000).

Procedures

Psychology students and professionals administered pen and paper questionnaires in a Brazilian host community in a small countryside city in Rio Grande do Sul, southern Brazil. The application of all instruments lasted around 40 minutes. This study was approved by the Scientific Board of the School of Psychology and the Ethical Research Committee of the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (n. 1.164.938). All participants completed the Terms of Free and Informed Consent and agreed to participate in the study.

One crucial side aspect of the analysis is the dropout cases. Nineteen cases (mostly men, 89.47%) who initially agreed to participate in the research decided not to continue answering the instruments when they found out its subject. Furthermore, the other 42 community inhabitants refused to participate in the study after reading the research topic in the Terms of Free and Informed Consent. All these cases were not included in the sample, but they are worth to be mentioned since they may reflect the host community’s resistance toward immigrants.

Data analysis

The collected data were codified, typed, and stored with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) program, version 21.0 for Windows. The dependent variables were the host ’community’s acculturative orientations, while sociodemographic variables, prejudice, and quality of life were used as independent variables. Initially, descriptive analyses were conducted, providing a panorama of the sample. Later, analyses were conducted on association (’Pearson’s correlation), the differences among averages (Student’s t-test), and multiple linear regressions, using the enter method, to indicate the explicative variables of the acculturative orientations adopted by the host community.

Results

The acculturative orientations of the host community concerning Haitian immigrants demonstrate a predominance of individualism (M = 25.57, SD = 6.61) and integration (M = 22.48, SD = 5.63), while segregation (M = 17.07, SD = 6.24), transformation (M = 15, SD = 6.74), exclusion (M = 13.56, SD = 5.97), and assimilation (M = 11.02, SD = 4.8) obtained lower scores. The modern racism scale showed that the affirmation of differences gained the highest score (M = 3.69, SD = 1.23), while denial of prejudice got a lower score (M = 2.82, SD = 1.01). Both spheres featured below average on the scale (>4).

By checking the relation among variables, the initial analysis looked at differences in averages between sociodemographic variables of the sample and variables of acculturation and racial prejudice. Surprisingly, the only significant result indicated that men scored higher than women in the denial of prejudice variables (t(88) = 2.3, p = .03) and the acculturative orientation of segregation (t(88) = 2.09, p = .04).

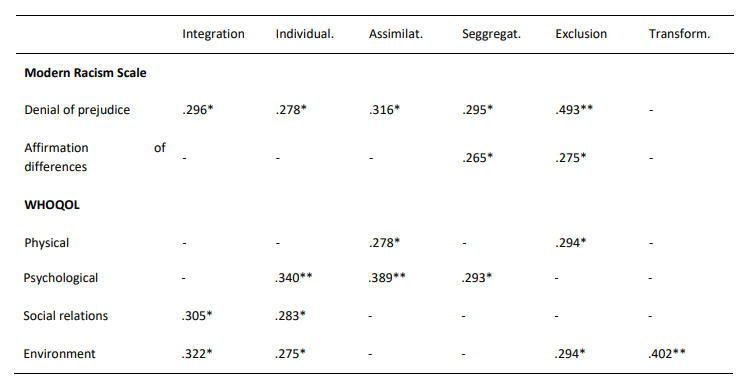

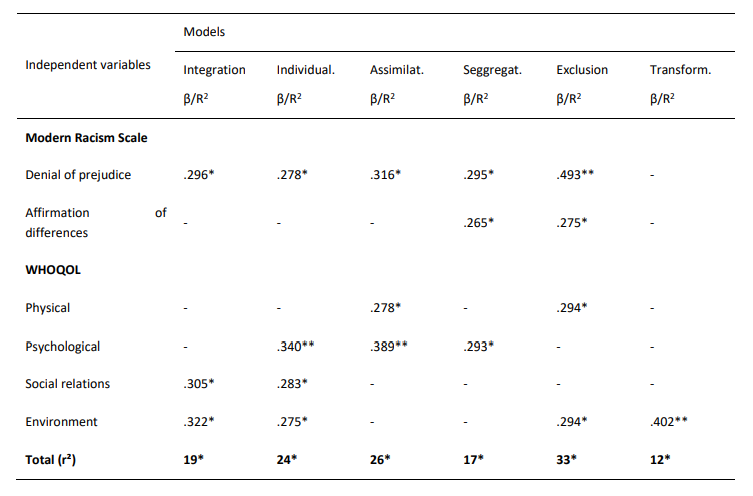

Analysis of Pearson’s correlation indicated with which acculturative orientation variables, racism, and quality of life were associated (Table 1). Linear regression was analyzed using the enter method for six acculturative orientations (Table 2).

Table 1. Significant Pearson’s Correlations among Acculturative Orientations, Racism, and Quality of Life

Notes. *p < .01

**p < .001.

Table 2. Multiple Linear Regressions for Acculturative Orientations Adopted by the Host Community toward Haitian Immigrants

Notes. *p < .01

**p < .001.

Analyses of linear regression show that the racial prejudice variables have explicative power over five of the six acculturative orientations approached. Integration and individualism orientations were more often adopted when the individuals revealed a lower score in the prejudice denial variable. At the same time, the assimilation, segregation, and exclusion orientations were explained by a higher score in the same variable, corroborating our hypothesis. Segregation and exclusión orientations were also explained by higher scores in the affirmation of differences variable. All the regression models were significant, with an acculturative orientation of exclusion having the highest explicative power (r² = .33) and the denial of prejudice variable as the leading factor for adopting this acculturative orientation (β = .47).

As expected, quality of life variables were associated with acculturative orientations. The highest score for quality of life in the psychological, interpersonal relations, and environment domains showed an explicative power for adopting acculturative orientations of integration, individualism, and transformation. On the other hand, we perceived that a quality of life score lower in the physical, psychological, and environment domains were factors that, on some level, forecast the adoption of assimilation, segregation, and exclusion acculturative orientations, partially corroborating our hypothesis.

Discussion

Study results demonstrate that the residents of the analyzed city showed a willingness to integrate the immigrants into the local community while also valuing the individual aspects of these people. In some cases, they demonstrated being open to making social modifications and changing their actions to improve the benefits of living with immigrants. However, to a lesser degree, there was evidence of adopting acculturative orientations of exclusion, assimilation, and segregation among the participants. This was primarily evident among men, who also tend to show the most racist attitudes. They appear significantly more inclined to adopt acculturative orientations of segregation and deny the existence of racial prejudice. This result can be associated with the refusal to conclude the questionnaires, which occurred with 19 participants, mainly men (89.47%). They initially agreed to participate in the study, though they dropped out when they discovered the subject. A similar situation occurred with the other 42 potential participants, who did not agree to participate in this study right after reading about the research topic in the presented Terms of Free and Informed Consent.

The choice for higher levels of adoption of acculturative orientations of integration and individualism corroborates studies in other contexts and with other migratory groups (Bourhis et al., 2009; Montreuil & Bourhis, 2001; Sapienza et al., 2010), demonstrating that the community under study is relatively receptive to Haitian immigrants. According to Bourhis et al. (2010), integration and individualism orientations, both from the social point of view and about state policy, are the acculturative orientations that provide immigrants with more satisfactory insertion into another context by perceiving respect for their culture and ways of living.

Racial discrimination also appeared as a factor directly influencing adopted acculturative orientations. The three less tolerant ones regarding integration and maintenance of the cultural reference of immigrants—segregation, exclusion, and assimilation—were associated with racism in both spheres studied – denial of prejudice and affirmation of differences. These results corroborate the literature (Bourhis et al., 2010; Rojas et al., 2014; Wagner et al., 2013) and reiterate that discrimination, racism, and xenophobia remain a structured social problem that affects minority groups in Brazil, such as Indigenous and Afro-descendant groups.

Additionally, we found that racial discrimination was mainly based on the affirmation of differences between white and black populations, as shown by Santos et al. (2006) in the validation study for the Modern Racism Scale in Brazil. Despite the score being higher for the affirmation of differences factor than the denial of prejudice factor, the latter demonstrated greater explicative power regarding the acculturative orientations adopted toward Haitian immigrants. The idea that racial prejudice does not exist in Brazil and that minority groups should face up to their problems without any form of help or special aid extends to how the studied communities position themselves regarding the acculturation process of Haitian immigrants (Santos et al., 2006). People who believe racism is something existent and pertinent to Brazilian society seem to be more receptive to Haitian immigrants and the maintenance of another ethnic and national identity, in comparison to a small portion of the population that denies the existence of racial discrimination as a social problem.

Even though no studies have been identified that associate quality of life with acculturative orientations, we found that in the four domains studied—physical, psychological, social relations, and environment—there was an association between the levels of quality of life and acculturative orientations. As such, a higher quality of life may provide an opening to the arrival and integration of immigrants, just like the orientations that reject the presence of immigrants are related to a lower perceived quality of life. Even though there is strong evidence regarding the associations between racial discrimination and poor physical and mental health in immigrants (Bergeron et al., 2020; Moline et al., 2019), little is known about prejudice and quality of life in host communities. This is an issue that could be addressed by future studies in order to understand the phenomena from a different perspective. Since the majority of studies on immigrants carried out in Brazil are eminently qualitative, and in order to better illustrate particularities of racism and discrimination against Haitians, we propose to discuss the results presented in this paper, also with findings from this approach.

Gomes (2017) aimed to address the narratives produced by Haitians in the capital of Santa Catarina, southern Brazil, through interviews and participant observation. Data analysis showed that none of the interviewed immigrants had any relationship or affective bonds with native citizens, even though most immigrants referred to Brazilians as welcoming people. Similar ambiguity was noticed when immigrants reported not having experiences with discrimination; however, the observation data shows segregation and exclusion against immigrants according to their ethnicity and nationality. There were also few narratives related to explicit discrimination, a fact that could lead to speculation that prejudice is not a frequent or even an actual phenomenon. Gondim et al. (2016) had similar results when conducting a group session interview with immigrants from different nationalities (Haitians included) regarding the ambivalence of the Brazilian community’s attitudes toward them regarding kindness and hostility. According to Gomes (2017), what can play an essential role in this ambiguity of Haitians not perceiving racist, xenophobic, or discriminative behaviors toward them while these take place are the differences in terms of language and cultural symbolic comprehension. These disparities could be a topic for future studies to lean over and better comprehend their associations.

On the other hand, contextual information may be another path to discuss the findings of this study thoroughly. Despite Brazil being traditionally seen as a welcoming nation, since its progressive immigration laws, even from an international perspective, there is a critical lack of public policies to guarantee other immigrants’ rights (Cá & Mendes, 2020). The available supportive initiatives are usually from civilian, religious, or philanthropic levels, as they turn into substitute approaches to provide minimum subsistence conditions for these people, such as shelter and food. This insufficiency of public policies in the country, associated with the rising perspectives of neoliberal and conservative ideology, may lead Brazilian society to an intensification of xenophobia against the immigrant population (Gomes & Miranda, 2018).

According to Bauman (2017), Brazilian society is already antagonistic and polarized regarding migration. Some progressive groups favor welcoming immigrants, with a humanitarian perspective of guaranteeing their rights. However, there are also neoliberal conservative groups against the admission of immigrants in the country, who identify themselves with all sorts of narratives such as “they are coming to steal our jobs” or “they want to survive only through government public policy.” Thus, the recent rise of extreme conservative parties in Brazil is enforcing this anti-immigration ideology, which can be associated with tendencies of racist and xenophobic behaviors toward immigrants (Oliveira, 2019). The phenomenon can be perceived at a micro-level in the data gathered since we had a high index of refusal from the host community to participate in the study. However, it can also be seen at the macro-level in politics since, in 2018, the president of Brazil withdrew from the United Nations Global Compact, unveiling the opposed position of the current extreme rightwing government regarding humanity immigration policies (Cá & Mendes, 2020).

In terms of advancing theoretical framework regarding prejudice toward immigrants, some authors suggest that only the definition of racism might not be enough to explain all sorts of implicit or explicit prejudice and discrimination immigrants may experience in a Brazilian host community, primarily due to the racist model that historically structures its society (Almeida, 2018). This also applies to the definition of xenophobia since European immigrants are differently welcomed in the country compared to Afro-descendant immigrants (Faustino & Oliveira, 2021; Oliveira, 2019). Therefore, Oliveira (2019) describes the “xenoracism” concept in order to emphasize how prejudice, discrimination, and xenophobic beliefs and attitudes are intertwined with structural racism when we take into perspective immigrants with specific phenotypes. This relatively new concept may shed light for future studies on how these biosocial markers can modify how the Brazilian host community applies different acculturation orientations to immigrants according to their ethnicity-phenotype.

Conclusions

This study aimed to identify the acculturative orientations adopted by a host community concerning Haitian immigrants in the countryside of Brazil and the influence of racial prejudice and quality of life perceived in these orientations. The proposed discussions demonstrate that, despite a higher rate of receptivity and respect for Haitian immigrants, racism and perceived quality of life are still factors that affect this process. The study results may serve as a subsidy for migratory and hosting policies sensitive to the particularities of the groups that arrive in Brazil. It is also important to consider that Haitian immigration into Brazil is a recent phenomenon and still relatively small compared to other countries. Thus, the results of this study should be viewed with caution, as the process of forming opinions about migration is still at an early stage.

The study is limited to approaching only a small Brazilian city in the south, and the results cannot be generalized for other contexts, especially given the diversity and plurality of a country the size of Brazil. For future studies, the perception regarding other groups of immigrants and refugees that have been exponentially increasing in the Brazilian context should also be studied, such as the Venezuelans, since they have been received, sheltered, and interiorized to small-medium cities in Brazil through a government task force (Silva et al., 2021; UNHCR, 2021). Investigations should also be carried out with other migratory groups who do not have race markers and involuntary migration for survival—groups of valued and devalued immigrants (Montreuil & Bourhis, 2001).

Based on the results identified, we would like to bring to mind the importance of a migratory policy that follows the integrative model, informing the population about the theme and focusing on actions that can tackle racial prejudice, which is the leading sphere in acculturative orientations that exclude immigrants from society. Promoting a better quality of life for the entire population also reflects an improvement in hosting new groups, fostering space for harmonious coexistence.