Introduction

Since the outset of the latest Colombian peace process between the Government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC)1 in September 2012, which ultimately produced the comprehensive peace agreement in November 2016 (hereafter, 2016 CPAF), a growing number of studies and official statements have emphasized the innovative approach used to address the grievances of the armed conflict2, and the numerous benefits that the end of the conflict would represent (Bouvier, 2016; Combita, Delgadillo, & Torres, 2013; Conciliation Resources, 2016; Cristo, 2016; De la Calle, 2016; Jackson, 2016; Herbolzheimer, 2016; Pizarro & Moncayo, 2015; Salvesen & Nylander, 2017)2016; Cristo, 2016; De la Calle, 2016; Herbolzheimer, 2016; Conciliation Resources, 2016; Bouvier, 2016; Salvesen & Nylander, 2017. However, notwithstanding the evidence offered by the Colombian Ministry of Defense (2017, 2018) on the improvement of the degree of security and the reduction of violence as possible results of the 2016 CPAF, several polls have shown a significantly negative perception of socioeconomic, political, security, and justice issues in the country among Colombian citizens (El Tiempo, 2018; Gallup, 2017b; RCN, 2016b; Semana, 2017b; Yanhass Poll, 2017).

A notable uncertainty concerning the 2016 CPAF has been documented, resulting from lack of understanding of its contents, which has already fostered misgivings about its implementation (El Tiempo, 2017a; Gallup, 2017a). In fact, as of February 2018, 39 % of Colombians believed that the 2016 CPAF has been evolving adequately; 15 % had a positive perception of the FARC, and only 38 % of the population believed that the FARC would honor its responsibilities stipulated in the agreement. In addition, some organizations such as the International Commission for the Verification of Human Rights in Colombia (2018) estimate that only 18.5 % of the provisions established have been implemented (El Espectador, 2018; El Pais, 2017; El Tiempo, 2018; Gallup, 2017b).

This sustained pessimism -which has remained unaltered since the signing of the peace agreement (El Colombiano, 2016; El Espectador, 2017, 2018; Gallup, 2017a)- has undermined governability in Colombia and the popular support essential to the implementation of the agreement. For instance, during 2017 only 18 % of the population believed that the situation in Colombia has improved, while only 24 % praised the administration of former Colombian President, Juan Manuel Santos Calderón (Gallup, 2017b); all of the above to uncertainty in the transition to a post-accord environment.

Accordingly, one of the most significant current discussions regarding conflict resolution in Colombia centers on the future of the 2016 CPAF. The concerns lie not only in the outcome of the Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) process of the most long-lived insurgent organization in Latin America (Serrano Alvarez, 2018; Torrijos Rivera & Abella Osorio, 2018; Valencia & Daza, 2010;), but also in the vastness of the matters agreed upon and, thus, in the duties of the Colombian government and the FARC to guarantee the full implementation of the agreement, which includes providing the Colombian population and the international community with a full understanding of the agreement to promote its support.

Most studies on the 2016 CPAF have examined its possible future effects on political (Botero & Herrera, 2017; Garay Acevedo & Guecha, 2018; Tesillo, 2016;), social (Cabrera Cabrera, Corcione Nieto, Figueroa Pedreros, & Rodriguez Macea, 2018; Ibanez, 2016; Puerta & Dover, 2017), economic (Medina, Pinzon, & Zuleta, 2017; Rettberg & Quiroga, 2016), and judicial (Bernal et al., 2017; Gomez, 2017) spheres. However, apart from the efforts made by the Colombian high commissioner for peace and some peace-supporting organizations such as Dejusticia (2017), Fundación Ideas para la Paz (2017a), and Común Acuerdo (2017) at the time of writing, little attention has been paid to the 310-page final agreement itself, which requires a full explanation to obtain a clearer picture of the contents of the entire peace process, in light of other international peace agreements.

This article seeks to fill this gap by examining the contents of the 2016 CPAF and drawing on data from the Peace Accord Matrix of the University of Notre Dame and the work of Högbladh (2012) in order to explain its essence and contest some of the criticism concerning it. Moreover, this article aims to determine the extent to which the 2016 CPAF has been a pioneering process regarding the provisions established. To this end, it first gives a brief overview of the traditional approaches used to characterize peace agreements by focusing on their provisions and presents a new five-group model to assess the 2016 CPAF. It then centers on the 2016 CPAF, depicting its similarities and differences with other peace agreements. Lastly, it reviews some of the 2016 CPAF'S major criticisms, as far as its extent and projected implementation level are concerned.

Literature and method: Identifying the essence of peace processes

In recent decades, there has been an intense discussion of the effectiveness of intrastate conflict resolution by means of soft power versus brute force. Although mass media and political discourses tend to praise peace agreements achieved through dialogue, numerous studies have found that these agreements are frequently unstable and likely to result in the recurrence of conflict (DeRouen, Lea, & Wallensteen, 2009; Lounsbery & DeRouen, 2016; Martinez & Diaz, 2005; Paris, 2004; Walter, 2004). These findings received increased attention from policymakers and negotiators, compelling them to use innovative formulas in new peace processes and driving them to include appropriate provisions into peace agreements to encourage successful conflict resolution and, subsequently, achieve effective peacebuilding3.

Academic literature on conflict analysis and resolution has also increased considerably; it closely examines peace agreements, their dynamics, and provisions included to characterize their contents, address grievances and prevent recurrences of violence (Álvarez Calderón & Rodriguez Beltrán, 2018; Cabrera Cabrera & Corcione Nieto, 2018; Fernandez-Osorio, 2017; Gonzalez Martinez, Quintero Cordero, & Ripoll De Castro, 2018). For instance, Bruch, Muffett, and Nichols (2016) discuss grievances originating from natural resources management; Caspersen (2017) explores grievances derived from inter-ethnic/state relations and security sector restructuring (a military and police reform); and Castro-Nunez et al. (2017) examine economic and social development-related grievances and their connection to land seizures.

One of the most widely used methodologies to characterize peace agreements is identifying its provisions. Provisions are understood here as "a goal-oriented reform or stipulation that (...) falls under a relatively discrete policy domain (e.g., executive branch reform, demobilization, minority rights, police reform)" based on Joshi and Quinn (2015, p. 15).

A significant body of literature, including works by Hartzell, Hoddie, and Rothchild (2001); Mattes and Savun (2010); Pettersson and Lotta (2012); Paffenholz (2014); Ansorg, Haass, and Strasheim (2016); Backer, Bhavnani, and Huth (2016); Kovacs and Hatz (2016); DeRouen and Chowdhury (2016); and Jeffery (2017) have examined the essence of peace agreements using their provisions as common themes to establish priorities that should be resolved between parties. However, the disparity in the grouping of provisions has hindered the compilation of these assessments. The UCDP, for instance, organizes these provisions into four groups: military, political, territorial, and judicial (Högbladh, 2012, p. 44), disregarding some important provisions, such as a military reform, reparations, and human rights, which could limit more indepth categorizations. Meanwhile, the PAM organizes them into five groups: institutions, security, rights, external arrangements, and miscellaneous (Joshi & Quinn, 2015, pp. 15-16).

To date, none of the published research on the 2016 CPAF has used either the PAM or UCDP' methodology to categorize its contents. However, in August 2016, the Colombian government and the FARC decided to assign the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame with the "principal responsibility for technical verification and monitoring of the implementation of the accord through the Peace Accords Matrix (PAM) Barometer initiative" (LaReau, 2016). With this in mind, we established that the best methodology for this research is the PAM approach to provide some innovative and useful input for present or future studies on the 2016 CPAF that will contribute to the assessment of the agreement implementation.

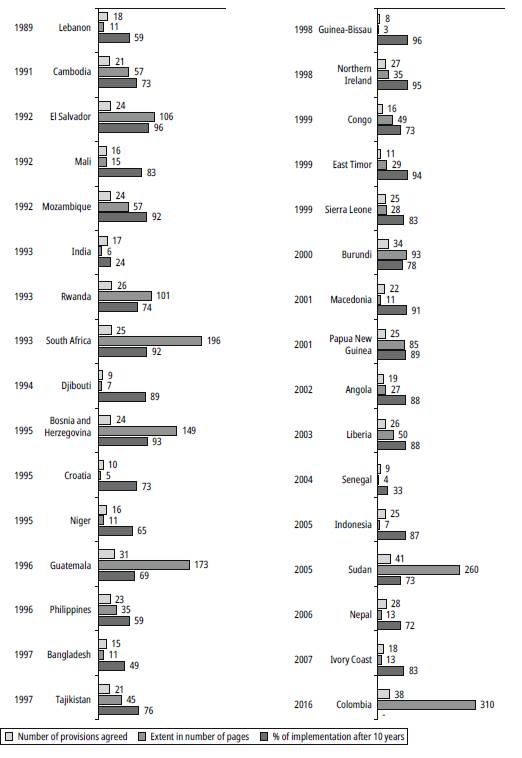

This article uses the set of peace agreement provisions and the definitions provided by the PAM, which has characterized the peace accords of 31 countries between 1989 and 2012 (Table 1).

Table 1 Peace Agreements (1989-2012) Coded by the Peace Accord Matrix

| Year | Country | Comprehensive peace agreement | Extent | Provisions | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | Lebanon | Taif accord (10/22/1989) | 11 | 18 | 59 % |

| 1991 | Cambodia | Framework for a comprehensive political settlement of the Cambodia conflict (10/23/1991) | 57 | 21 | 73 % |

| 1992 | El Salvador | Chapultepec peace agreement (01/16/1992) | 106 | 24 | 96 % |

| 1992 | Mali | National pact (04/11/1992) | 15 | 16 | 83 % |

| 1992 | Mozambique | General peace agreement for Mozambique (10/04/1992) | 57 | 24 | 92 % |

| 1993 | India | Memorandum of Settlement (Bodo Accord) (02/20/1993) | 6 | 17 | 24 % |

| 1993 | Rwanda | Arusha accord (08/04/1993) | 101 | 26 | 74 % |

| 1993 | South Africa | Interim constitution accord (11/17//1993) | 196 | 25 | 92 % |

| 1994 | Djibouti | Accord de paix et de la reconciliation nationale (12/26/1994) | 7 | 9 | 89 % |

| 1995 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | General framework agreement for peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina (11/21/1995) | 149 | 24 | 93 % |

| 1995 | Croatia | Erdut agreement (11/12/1995) | 5 | 10 | 73 % |

| 1995 | Niger | Agreement between the Republic Niger government and the ORA (04/15/1995) | 11 | 16 | 65 % |

| 1996 | Guatemala | Accord for a firm and lasting peace (12/29/1996) | 173 | 31 | 69 % |

| 1996 | Philippines | Mindanao final agreement (09/02/1996) | 35 | 23 | 59 % |

| 1997 | Bangladesh | Chittagong hill tracts peace accord (12/02/1997) | 11 | 15 | 49 % |

| 1997 | Tajikistan | General agreement on the establishment of peace and national accord in Tajikistan (06/27/1997) | 45 | 21 | 76 % |

| 1998 | Guinea-Bissau | Abuja peace agreement (11/01/1998) | 3 | 8 | 96 % |

| 1998 | Northern Ireland (UK) | Northern Ireland good friday agreement (04/10/1999) | 35 | 27 | 95 % |

| 1999 | Congo | Agreement on ending hostilities in the Republic of Congo (12/29/1999) | 49 | 16 | 73 % |

| 1999 | East Timor | Agreement between Indonesia and the Portuguese Republic on the question of East Timor (05/05/1999) | 29 | 11 | 94 % |

| 1999 | Sierra Leone | Lome peace agreement (07/07/1999) | 28 | 25 | 83 % |

| 2000 | Burundi | Arusha peace and reconciliation agreement for Burundi (08/28/2000) | 93 | 34 | 78 % |

| 2001 | Macedonia | Ohrid agreement (08/13/2001) | 11 | 22 | 91 % |

| 2001 | Papua New Guinea | Bougainville peace agreement (08/30/2001) | 85 | 25 | 89 % |

| 2002 | Angola | Luena memorandum of understanding (04/04/2002) | 27 | 19 | 88 % |

| 2003 | Liberia | Accra peace agreement (08/18/2003) | 50 | 26 | 88 % |

| 2004 | Senegal | General peace agreement between the government of the Republic of Senegal and mfdc (12/30/2004) | 4 | 9 | 33 % |

| 2005 | Indonesia | MoU between the government of the Republic of Indonesia and the Free Aceh movement (08/15/2005) | 7 | 25 | 87 % |

| 2005 | Sudan | Sudan comprehensive peace agreement (01/09/2005) | 260 | 41 | 73 % |

| 2006 | Nepal | Comprehensive peace agreement (11/21/2006) | 13 | 28 | 72 % |

| 2007 | Ivory Coast | Ouagadougou political agreement (03/04/2007) | 13 | 18 | 83 % |

Note. "Extent" is given in pages. "Provisions" is the number of provisions agreed in the accord. "Implementation" is the percentage after ten years.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2018).

However, it reorganizes them into a new model, which is explained in Table 2. Provisions are organized into five groups: socioeconomic, political, security and defense, justice, and implementation and verification. These are the provisions that best match the six major topics of the official agenda discussed by the Colombian government and the FARC (2016) during the 2012-2016 peace process, which include: (i) a comprehensive rural reform, (ii) political participation, (iii) ending the conflict, (iv) resolving the illicit drugs issue, (v) victims of the conflict, and (vi) the agreement implementation, verification, and endorsement. A comprehensive rural reform and resolving the drug issues were merged into the first group (socioeconomic provisions) as both topics share most of the provisions established.

Table 2 Proposed Grouping Model for pam's Provisions Based on the Agenda of the 2016 CPAF

| (Comprehensive rural reform and resolving the illicit drug issue) | (Political participation) | (End of conflict) (Victims of the conflict) | (Implementation, verification, and endorsement) | ||

| Children’s rights | Boundary demarcation | Arms embargo | Amnesty | Detailed implementation timeline | |

| Cultural protections | Citizenship reform | Ceasefire | Commission to address damage | Dispute resolution committee | |

| Economic and social development | Civil administration reform | Demobilization | Internally displaced persons | Donor support | |

| Education reform | Constitutional reform | Disarmament | Judiciary reform | International arbitration | |

| Human rights | Decentralization/ federalism | Military reform | Prisoner release | Ratification mechanism | |

| Indigenous minority rights | Electoral/political party reform | Paramilitary groups | Refugees | Regional peacekeeping force | |

| Media reform | Executive branch reform | Police reform | Reparations | Review of agreement | |

| Minority rights | Independence referendum | Reintegration | Truth or reconciliation mechanism | un peacekeeping force | |

| Natural resource management | Legislative branch reform | Withdrawal of troops | un transitional authority | ||

| Right of self- determination | Official Language and Symbol | Verification/monitoring mechanism | |||

| Women’s rights | Power-sharing transitional government | ||||

| Inter-ethnic/state relations | Territorial power sharing | ||||

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2015) and Colombian Government & FARC (2016).

Characterization of the 2016 comprehensive peace agreement with the FARC

Negotiations towards the 2016 CPAF officially began in September 2012, with a defined six-point framework, and lasted until a final agreement was announced on August 24, 2016. While the peace process had many supporters in Congress, in major social movements, and international organizations, disapproval among the population grew significantly, resulting from the lack of clear information on the peace talks in Havana, Cuba, and the agreement's partial accords. This uncertainty generated trepidation about the future of the country and certain socioeconomic, political, security, and justice aspects. The ratification referendum of the final agreement in October 2016 achieved the highest degree of uncertainty, resulting in 50.2 % of voters rejecting the accord (BBC, 2016). This outcome made it clear to the Colombian government, the FARC and the international community that the majority of the population had misunderstood the whole process and the established provisions.

Despite the strong international support, including the awarding of the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize to former Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos Calderon, the referendum results forced a renegotiation of the accord, which was finally ratified by the Colombian Congress on November 30, 2016. This reviewed version of the final accord added 13 pages to the original 297-page document. These pages included several explanations regarding the definitions and procedures used to reach the established provisions; it also included some modifications thereto required by the opposition and social movements. Some of these key changes contained the protection of private property and legal landowners; the establishment of a statute for political opposition; and the inclusion of guarantees for peaceful protests. The new pages also included regulations regarding the assignment of public funding to FARO'S political party; the inclusion of FARC militias into the DDR process; stipulations obliging the FARC to end its illegal economic activities and provide accurate information on its finances and assets; the funds deemed illegal to be used for victim reparations and address any damages caused; some procedures to guarantee the security of FARC leaders and combatants; guidelines regarding the substitution of illicit crops, including aerial aspersion; actions to ensure the political participation of FARC'S representatives; the creation of dedicated media and radio stations for FARC'S political party; and finally, guidelines and procedures for a transitional justice system (Fundacion Ideas para la Paz, 2017b; High Commissioner for Peace, 2016e; Lopez, 2016).

The 2012-2016 peace process with the FARC yielded an exploratory agreement called The General Agreement for Ending the Conflict and Building Stable and Enduring Peace, five joint reports, 13 drafts of supporting texts, 107 joint declarations, and a final agreement called The Final Agreement to End the Conflict and Build Stable and Durable Peace (the 2016 CPAF), a total of 136 documents. After the final agreement, the exploratory document was perhaps the most important one. It established the agenda and the topics to be discussed, as well as the general guidelines for the peace process. Based on the descriptions by the pam, 38 provisions can be identified to assess the 2016 CPAF final agreement (Table 2) from the five-group model of provisions formulated by this article. These provisions can be organized as follows:

Socioeconomic provisions. This first group, consisting of twelve provisions, establishes the way that the 2016 CPAF deals with socioeconomic grievances and describes its strategy in solving the first and fourth topics of the peace process agenda (i.e., a comprehensive rural reform and resolving the illicit drug issue). These provisions are children's rights, cultural protection, economic and social development, an education reform, human rights, indigenous and minority rights, a media reform, natural resource management, rights of self-determination, women's rights, and inter-ethnic and state relations.

Figure 1 shows that Colombia has the most socioeconomic provisions in its peace agreement, namely, twelve occurrences, while some countries such as Guinea-Bissau and Côte d'lvoire have none. In comparison to other peace agreements, this number is well above the median (3) for this group (Table 3).

Table 3 Descriptive Statistics of Socioeconomic Provisions

| Mean | 3.94 |

| Standard Error | .55 |

| Median | 3 |

| Mode | 2 |

| Standard Deviation | 3.11 |

| Range | 12 |

| Count | 32 |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2018).

Note. Colombia's 2016 CPAF is included. Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2015) and Colombian Government & FARC (2016).

Figure 1 Socioeconomic Provisions Included in Peace Agreements (1989-2016) by Country

To address the required comprehensive rural reform, this group of provisions covers historical problems to be resolved at a national level but with a territorial approach that includes access to and use of land; formalization of rural property for untitled proprietors; improvement of the rural cadaster; protection of special environmental interest areas; rural jurisdiction to resolve conflicts; infrastructure; adequate housing; access to drinking water and sanitation, social security; education; health, food and nutrition; and a solidary and cooperative rural economy (Común Acuerdo, 2017; High Commissioner for Peace, 2016d). Conversely, these provisions related to the illicit drug issue, that is, the eradication and substitution of illicit crops, the prevention and treatment of drug use with a public health approach, and the fight against drug trafficking and organized crime (High Commissioner for Peace, 2016f).

Of the 31 peace agreements analyzed, 94 % include at least one provision from this group, economic and social development (69 %) and human rights (63 %), these are the most employed provisions; the right to self-determination is the least used provision (16 %) (Figure 2). Notably, the provisions less employed internationally were children's rights (19 %), indigenous minority rights (19 %), minority rights (19 %), and rights of self-determination (16 %); all of which are explicitly addressed by the 2016 CPAF. Moreover, the provision on women's rights (25 %) was expanded to cover other gender identities as well, incorporating the rights of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community (Colombian Government & FARC, 2016).

Note. Colombia's 2016 CPAF is included. Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2018) and Colombian Government & FARC (2016).

Figure 2 Percentage of Peace Agreements with Socioeconomic Provisions (1989-2016)

The 2016 CPAF'S objective is to boost the rural reform and to reduce rural poverty by 50 % within ten years, through the creation of a land bank to assign rural parcels to farmers, victims, and minorities. Means of production and infrastructure are to be procured through popular participation in regional decisions addressing uneven land distribution to develop local and familiar economies, narrow the rural-urban gap, recover the zones affected by the armed conflict, and protect regional multiculturalism (High Commissioner for Peace, 2016d). The implementation of this group of provisions is possibly one of the most critical challenges of this agreement, as even the most optimistic economic assessments forecast a tough economic future for Colombia (Figure 3).

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from DANE (2016), World Bank (2017), and Banco de la República (2017).

Figure 3 Evolution of Major Economic Indexes in Colombia (2012-2016)

Political provisions. The twelve provisions of this second group involve how the 2016 CPAF addresses equal political participation and administrative issues that have caused or aggravated the armed conflict. It also provides solutions to the second topic of the peace process agenda, that is, political participation. Such provisions consist of boundary demarcation and citizenship, civil administration, a constitutional reform, decentralization/federalism, an electoral/political party reform, and executive branch reforms, as well as an independence referendum, a legislative branch reform, official language and symbols, power sharing during the transitional government, and territorial power sharing.

Figure 4 shows that the 2016 CPAF comprised only four provisions related to this group (a civil administration reform, a constitutional reform, an electoral/political party reform, and a legislative branch reform); this number is the median (4) for this group (Table 4). However, it is low compared to Sudan (ten provisions), Bosnia Herzegovina, the Philippines, and South Africa (eight provisions each).

Table 4 Descriptive Statistics of Political Provisions

| Mean | 4.53 |

| Standard Error | .43 |

| Median | 4 |

| Mode | 3 |

| Standard Deviation | 2.44 |

| Range | 10 |

| Count | 32 |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2018).

Note. Colombia's 2016 CPAF is included. Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for Institute for International Peace Studies (2018) and Colombian Government & FARC (2016).

Figure 4 Political Provisions Included in Peace Agreements (1989-2016) by Country

To resolve grievances related to this group of provisions, the 2016 CPAF encourages forming new political parties, strengthening transparency in electoral processes, increasing the population's democratic involvement, promoting the integration of regions affected by the armed conflict into politics, guaranteeing the political representation of minorities, social movements, victims and stigmatized regions, and establish security protocols aiming to protect FARC members (High Commissioner for Peace, 2016c; Común Acuerdo, 2017).

This agreement was innovative in terms of the measures used to tackle some of the most common challenges in the implementation of peace accords, such as corruption and lack of transparency, violent detractors, and the absence of appropriate conditions for political opposition (Colombian Government & FARC, 2016). Corruption affects the adequate use of resources and precludes the accountability of public organizations and officials, especially when dealing with a post-accord scenario, in which funding is often scarce. To foster transparency, the 2016 CPAF aimed to secure the completion of projects adopted by creating a national council for reconciliation and coexistence and a comprehensive security system for the exercise of politics. The agreement protects opposition leaders, social movements and human rights activists from violent detractors, while promoting a democratic environment for political participation and discussion.

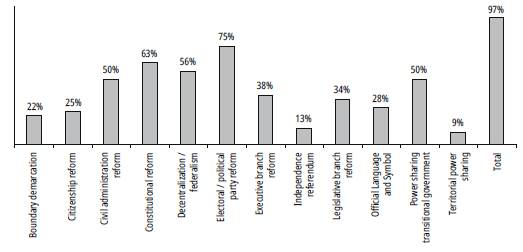

It is possible that other provisions were not included in Colombia's peace agreement because of its reliance on the exploratory document in which strict limits were imposed as conditions for the peace talks. For example, the issues of an executive branch reform, a military/police reform, decentralization/federalism, a power sharing transitional government, and territorial power sharing were excluded, as the government's intention was not to modify the state's structure or administration. Provisions involving areas such as boundary demarcation, a citizenship reform, an independence referendum, and official language and symbols were also excluded in the exploratory document and external to discussion by the parties (Colombian Government & FARC, 2012). In general, 97 % of the peace agreements assessed included at least one provision from this group. An electoral/political party reform (75 %) and a constitutional reform (63 %) were the provisions most used, while territorial power sharing (9 %) was the least used (Figure 5).

Note. Colombia's 2016 CPAF is included. Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2018) and Colombian Government & FARC (2016).

Figure 5 Percentage of Peace Agreements with Political Provisions (1989-2016)

Defense and security provisions. The nine provisions in this third group show how the 2016 CPAF addresses defense and security challenges for the post-accord scenario and provide options for the third topic of the peace process agenda (end of armed conflict). These provisions are arms embargo, ceasefire, demobilization, disarmament, a military reform, paramilitary groups, police reform, reintegration, and withdrawal of troops.

The 2016 CPAF involves only six security and defense provisions (ceasefire, demobilization, disarmament, paramilitary groups, reintegration, and withdrawal of troops). In comparison to other peace agreements, this number is the median for this group (6) (Table 5).

Table 5 Descriptive Statistics of Defense and Security Provisions

| Mean | 5.59 |

| Standard Error | .33 |

| Median | 6 |

| Mode | 5 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.88 |

| Range | 7 |

| Count | 32 |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2018).

According to Figure 6, Sudan had nine occurrences, while Angola, Burundi, Cambodia, and Mozambique had eight, being the countries that included the most provisions of this type. Conversely, Croatia and Guinea-Bissau had the fewest provisions (two occurrences).

Note. Colombia's 2016 CPAF is included. Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2018) and Colombian Government & FARC (2016).

Figure 6 Defense and Security Provisions Included in Peace Agreements (1989-2016) by Country

The implementation of this group is perhaps the most successful. As of July 2017, after a phase of ceasefire and a bilateral end to hostilities, a structure for the monitoring and verification of the DDR mechanism (formed by the United Nations, the Colombian Government and FARC) was established. Approximately 7,000 FARC members were demobilized and distributed among 19 zones (El Tiempo, 2017b). The United Nations mission in Colombia oversaw and verified FARC'S disarmament. FARC'S decommissioned armament, estimated to include 7,132 large and small guns, was stored in containers under the UN'S control (Semana, 2017a). Humanitarian demining programs led by the National Army of Colombia have also been successful (Accion contra minas, 2016), 660 weapon caches in remote areas were collected and destroyed by the un and the National Army of Colombia (United Nations, 2017). The National Army of Colombia and the National Police have provided security to FARC'S demobilized personnel. A new strategy has even been implemented to manage FARC dissidents who chose to ignore the peace agreement and characterized them as armed groups in order to guarantee social, economic, and political reintegration of FARC members (High Commissioner for Peace, 2016a).

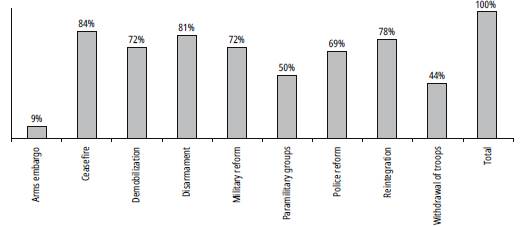

Figure 7 shows that all the 31 peace agreements analyzed included at least one security and defense provision. The most used provisions were those related to the DDR process: demobilization (84 %), disarmament (81 %), and reintegration (78 %). The least used was arms embargo (9 %). Two of the key provisions, a military reform (72 %) and a police reform (69 %), were not included in the 2016 CPAF, as they had been deemed prohibited issues by the Colombian government in the exploratory document (Colombian Government & FARC, 2012). Similarly, the arms embargo provision was not discussed by the parties based on FARC'S commitment to voluntarily relinquish its weaponry and refrain from using violent means.

Note. Colombia's 2016 cpaf is included. Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2018) and Colombian Government & FARC (2016).

Figure 7 Percentage of Peace Agreements with Defense and Security Provisions (1989-2016)

Justice provisions. This fourth group comprises eight provisions and defines how the 2016 CPAF tackles equality and impartiality while addressing the fifth topic of the peace process agenda (victims of the conflict). These provisions are an amnesty, a commission to addressing damage/loss, internally displaced persons, a judiciary reform, prisoner release, refugees, reparations, and a truth or reconciliation mechanism.

The 2016 CPAF agreement includes all of these justice provisions (eight occurrences), a number that is well above the median (4) for this group (Table 6), in comparison to the other 31 peace agreements analyzed, such as East Timor and Philippines, which include none (Figure 8).

Table 6 Descriptive Statistics of Justice Provisions

| Mean | 3.69 |

| Standard Error | .31 |

| Median | 4 |

| Mode | 4 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.73 |

| Range | 8 |

| Count | 32 |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2018).

Note. Colombia's 2016 CPAF is included. Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2018) and Colombian Government & FARC (2016).

Figure 8 Justice Provisions Included in Peace Agreements (1989-2016) by Country

The 2016 CPAF incorporates a novel scheme to solve justice grievances and victims' rights, through a transitional justice system that is built upon a comprehensive structure of truth, justice, reparation and non-repetition; the creation of a commission for the clarification of truth, coexistence and non-repetition; the formation of a unit for the search of missing persons; the development of comprehensive reparation measures for peacebuilding; a special jurisdiction for peace; non-repetition guarantees; and giving historical memory a central role within the reconciliation process (High Commissioner for Peace, 2016g).

This group of provisions is probably one of the most controversial in Colombia, as the conflict and its complex origins have produced numerous victims, countless damages and a number of human rights violations (Pizarro & Moncayo, 2015). Striking an appropriate balance between justice and peace is the task for the transitional justice system approved by the parties, and endorsed by international political leaders. However, it is still under review of the International Criminal Court and human rights organizations (International Criminal Court, 2016).

Figure 9 depicts how 94 % of the agreements included at least one justice provision. The most used were internally displaced persons (72 %) and refugees (69 %), while the ones used the least involved a commission to addressing damage/loss (6 %) and reparations (25 %).

Note. Colombia's 2016 CPAF is included. Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2018) and Colombian Government & FARC (2016).

Figure 9 Percentage of Peace Agreements with Justice Provisions (1989-2016)

Implementation and verification provisions. This fifth group, consisting of ten provisions, explains how the 2016 CPAF addresses the sixth topic of the agenda (implementation, verification, and endorsement). These provisions are a detailed implementation timeline, a dispute resolution committee, donor support, international arbitration, a ratification mechanism, regional peacekeeping force, review of agreement, a UN peacekeeping force, a UN transitional authority, and a verification/monitoring mechanism.

The 2016 CPAF includes eight implementation and verification provisions (detailed implementation timeline, a dispute resolution committee, donor support, international arbitration, a ratification mechanism, review of agreement, a UN transitional authority, and a verification/monitoring mechanism), a number well above the median of this group (4) in comparison to the other 31 peace agreements analyzed (Table 7).

Table 7 Descriptive Statistics of Implementation Provisions

| Mean | 4 |

| Standard Error | .39 |

| Median | 4 |

| Mode | 3 |

| Standard Deviation | 2.21 |

| Range | 8 |

| Count | 32 |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2018).

This agreement has developed a unique approach to ensure compliance with peace initiatives and strategies through the continous verification of the implementation status to identify delays and adjustments needed. To this end, a follow-up and verification commission for the final peace agreement, as well as a mechanism to verify the agreement, were created (High Commissioner for Peace, 2016b). Similarly, the exploratory agreement of the 2016 CPAF promoted considerably constant assistance during the peace talks, both internationally with Cuba and Norway as guarantors and nationally with Chile and Venezuela. Also included were a citizen participation mechanism, a rapporteur system, and a promulgation mechanism. The agreement created the possibility for multilateral participation by academia, social movements, and citizens, expanding the scope of the topics discussed in Havana. The rapporteur system is led by the Universidad Nacional, and the promulgation mechanism, via a dedicated web page, as well as pedagogical campaigns that fostered transparency and enabled constant and necessary feedback.

The 2016 CPAF does not contain the following two provisions: regional peacekeeping force and un peacekeeping force as the parties agreed not to employ foreign troops in its implementation.

Colombia and Burundi, with eight occurrences, are the countries that have the most provisions of this type, in contrast to Djibouti, India, and Senegal that had no occurrences (Figure 10). Figure 11 depicts that 91 % of the agreements included at least one implementation and verification provision. The most utilized is the verification mechanism (78 %) and the detailed implementation timeline (69 %), while the least employed is international arbitration (6 %) and un transitional authority (13 %).

Note. Colombia's 2016 CPAF is included. Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2015) and Colombian Government & FARC, 2018.

Figure 10 Implementation Provisions Included in Peace Agreements (1989-2016) by Country 8 8

Note. Colombia's 2016 CPAF is included. Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2018) and Colombian Government & FARC (2016).

Figure 11 Percentage of Peace Agreements with Implementation Provisions (1989-2016)

Extension as another source of criticism

Another source of criticism for the 2016 CPAF is its extension and complexity, which promote conflicting and sometimes irreconcilable interpretations of its essence and implementation among the government, the opposition, the FARC, social movements, and international organizations. These misunderstandings involve many critical provisions, such as an amnesty (Sanchez, 2016), an electoral/political party reform (El Pais, 2016), human rights (International Committee of the Red Cross, 2017), a judiciary reform (The New York Times, 2016), transitional justice (Brodzinsky, 2016), reintegration (Aidi, 2016), a detailed implementation timeline (The Economist, 2017), economic and social development (Vivanco, 2016b), demobilization (Gomerzano, 2016), an education reform and children's rights (Oppenheimer, 2016), and the truth or reconciliation mechanism (Vivanco, 2016a).

Published studies on peace agreements have previously reported skepticism and grievances resulting from the lack of understanding of its contents. For instance, Spears (2000) demonstrated the instability of peace agreements in Africa due to persisting unfamiliarity with power-sharing provisions. Stanley and Holiday described in Stedman, Rothchild, and Cousens (2002, p. 442) the complications of the un mission in Guatemala (MINU-GUA) because of "a lack of understanding of most Guatemalans regarding the mission's mandate and functions." Mac Ginty, Muldoon, and Ferguson (2007) explained how political and psychological stubbornness destabilized the post-peace accord environment in Northern Ireland. As a result, mass media in Colombia has been instrumental in creating an adverse perception on the part of the accord's main critics, political opponents, and independent groups using the idea that the extensive number of pages of the 2016 CPAF has negatively impacted the reliability of the topics established, and that the high number of topics adversely affected the agreement implementation (CNN, 2016; El Tiempo, 2017c; Negrete, 2017; RCN, 2016a; Rendon, 2017; Semana, 2016).

Given such criticism, could there be a possible correlation between the extent of a peace accord and the number of provisions agreed upon, or between the number of pages or provisions established and the implementation level of the agreement? If such a hypothesis is accurate, in comparison to other countries, Colombia's 2016 CPAF and its implementation may have an uncertain future with agreements covering only 38 provisions within a 310-page document.

Regarding the first part of the question, although some peace agreements have a high number of established provisions vis-a-vis the extent (in pages) of the final accord, such as Indonesia with 25 provisions on seven pages, and India with 17 provisions on six pages, there are also peace agreements such as Mali's, with 16 provisions on 15 pages, and Sierra Leone's with 25 provisions on 28 pages. By running a regression of pam's data, it was possible to determine that there is a significant potential correlation between the extent (in pages) of a peace agreement and the number of provisions agreed upon, according to Pearson's r (30) = .73, p < .001 (Table 8). This suggests that the more pages a peace agreement has, the more provisions it will have.

Table 8 Summary of Regression Statistics (Extent vs Number of Provisions)

| Multiple R | .731 |

| P-value | .000 |

| R Square | .535 |

| Adjusted R Square | .520 |

| Standard Error | 5.486 |

| Observations | 32 |

Note. α = .05; Colombia's 2016 CPAF is included.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc

As to the second part of the question, there are also some short peace agreements with a high percentage of implementation level. Guinea-Bissau, for example, has a 96 % implementation level, ten years after the signing of a three-page agreement. Croatia has a 73 % implementation level of a five-page agreement. There are also multifaceted peace agreements, such as El Salvador's, with a 96 % of implementation level ten years after signing a 106-page agreement, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a 93 % implementation level of a 149-page agreement. The regression results of PAM'S data did not show any significant correlation between the extent (in pages) of a peace agreement and its implementation level, according to Pearson's r (29) = .20, p > .001 (Table 9). The results suggest that the implementation level of a peace agreement is not directly influenced by its extension; in other words, the success or failure in the implementation of a peace agreement does not depend on the complexity of the vetted documents of a peace process.

Table 9 Summary of Regression Statistics (Extent vs Implementation Level)

| Multiple R | .200 |

| P-value | .280 |

| R Square | .040 |

| Adjusted R Square | .007 |

| Standard Error | 17.695 |

| Observations | 31 |

Note. α = .05; Colombia's 2016 CPAF is not included.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2018).

Similarly, whereas there are some peace agreements with few agreed provisions and a high percentage of implementation level, such as Djibouti's with a 89 % implementation a ten years after the signing of a nine-provision agreement, and East Timor's with a 94 % implementation level of an 11-provision agreement, there are also intricate peace agreements, such as Sudan's, with a 73 % implementation level ten years after the signing of a 41-provision agreement, and Burundi's with a 78 % implementation level of a 34-provision agreement. The regression results of pam's data did not show a significant correlation between the number of agreed provisions and its implementation level, Pearson's r (29) = .17,p > .001 (Table 10). Therefore, it is possible to confirm that the implementation level of a peace agreement is not directly influenced by its complexity, in terms of the number of provisions agreed upon.

Table 10 Summary of Regression Statistics (Number of Provisions vs Implementation Level)

| Multiple R | .178 |

| P-value | .337 |

| R Square | .032 |

| Adjusted R Square | -.002 |

| Standard Error | 17.772 |

| Observations | 31 |

Note. α = .05; Colombia's 2016 CPAF is not included.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2018).

Conclusions

The results of the characterization of the 2016 CPAF based on the pam classification helped to identify the essence of the agreement and its future outlook. For instance, the 2016 CPAF is the longest agreement written since 1989 (310 pages) and the second in complexity after Sudan's based on the number of provisions agreed upon (38). Thirty-eight provisions, summarized in Table 11, describe its contents based on international standards and point to a number of aspects that are useful for future peace processes in Colombia with other insurgent organizations such as the ELN.4

Table 11 Provisions of the 2016 CPAF

| Type of provision and relevant | Provisions | |

|---|---|---|

| topic in the agenda | ||

| Children’s rights | Media reform | |

| 1. Socioeconomic | Cultural protections | Natural resource management |

| Comprehensive rural reform | Economic and social development | Natural resource management |

| Solving the illicit drug issue | Education reform | Right of self-determination |

| Human rights | Women’s rights | |

| Indigenous minority rights | Inter-ethnic/state relations | |

| 2. Political | Civil administration reform | Electoral/political party reform |

| Political participation | Constitutional reform | Legislative branch reform |

| Ceasefire | Paramilitary groups | |

| 3. Defense and security | Demobilization | Reintegration |

| End of conflict | Disarmament | Withdrawal of troops |

| Amnesty | Prisoner release | |

| 4. Justice | Commission to address damage | Refugees |

| Victims of the conflict | Internally displaced persons | Reparations |

| Judiciary reform | Truth or reconciliation mechanism | |

| Detailed implementation timeline | Ratification mechanism | |

| 5. Implementation and verification | Dispute resolution committee | Review of agreement |

| Implementation, verification, and | Donor support | un transitional authority |

| endorsement | International arbitration | Verification/monitoring mechanism |

Source: Created by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2018) and Colombian Government & FARC (2016).

The agreement is not as innovative as official publicity and mass media have declared; although it did include several pioneering ideas, such as the concepts of historical memory, missing persons, guarantees for political opposition and peaceful protests, victims' reparations, and comprehensive transitional justice, its foundations remain conservative and are close to international practices in conflict resolution. The number of socioeconomic provisions established in the 2016 CPAF (12 occurrences) is well above the median of this group of provisions (three occurrences). Similarly, the number of provisions established concerning justice and implementation and verification grounds is above the median of these groups (eight occurrences in comparison to four occurrences in both cases). Alternatively, the amount of agreed political provisions is equal to the median of the group (four occurrences) and the number of defense and security provisions agreed upon is equal to the median of the group (six occurrences).

International experience is fundamental when planning strategies to improve and stimulate the implementation of a peace agreement and to enhance civil-military relations (Durán, Adé, Martinez, & Calatrava, 2016; Mares & Martinez, 2014; Martinez, 2007; Martinez & Durán, 2017; Martinez, Adé, Durán, & Diaz, 2013; Pion-Berlin & Martinez, 2017). However, every case should be thoughtfully assessed to understand the origins of the conflict and the grievances that have so far hindered effective resolution initiatives, the contents and background of the peace agreement, and the best procedures to guarantee its implementation, and an overall successful reconciliation process.

Criticism on the 2016 CPAF related to its extension, complexity, and possibilities of implementation lacks support. Figure 12 summarizes the statistical results presented in this article, suggesting that, notwithstanding a possible correlation between the extension (in pages) of a peace agreement and the number of provisions agreed upon, there is no reasonable correlation between the extension and its implementation level, or between the number of provisions established in a peace agreement and its implementation level. Therefore, the results of the 2016 CPAF depend principally on the adequacy of the implementation plan, and on gaining popular support and increasing legitimacy.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2018) and Colombian Government & FARC (2016).

Figure 12 Characteristics of Peace Agreements (1989-2012) in Comparison to Colombia's 2016 CPAF

Popular encouragement, transparency and a shared sense of rightfulness are essential when dealing with peace agreements, occurring in the context of an unstable environment. Particularly, when other parties are still focused on armed conflict or illegal enterprises, and while there are limited resources available for the agreement implementation. It is thus necessary for the Colombian government and the FARC to explore context-specific, and at the same time, democratic and participative strategies, so that the stability of the agreement can be ensured for years to come.