Introduction

Organ transplantation is the cutting-edge approach for treating end-stage organ diseases like cirrhosis or heart failure 1. Replacement of the damaged organ with a fully functioning one brings better outcomes than any pharmacological therapy, improving survival, augmenting life expectancy, and reducing the cost of attention 2,3. Every year, thousands of transplants are performed worldwide, with great results for the recipient 3.

For more than a decade, the increasing sizes of waiting lists have raised significant concerns, primarily due to the substantial imbalance in the number of potential donors 4. Organs for transplantation primarily come from two sources: living donors (LD) and deceased donors (DD); it can be further categorized based on the type of death: death determined by circulatory criteria (DCC) and death determined by neurological criteria (DNC) 5. In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) received reports of transplant programs from 98 countries 6. However, these programs exhibit substantial variations due to sociocultural, religious, technical, and economic disparities 7. Certain countries, such as Iran and Saudi Arabia, exclusively depend on LD; while others maintain mixed programs that incorporate both LD and DD, although the proportions differ 6. In Colombia, currently, there are no transplant programs with DCC 8.

Due to the variations in practices across different regions and countries, significant differences arise in the characteristics of the donor pool, the criteria for selecting donors, and their utilization.

The critical pathway in Colombia

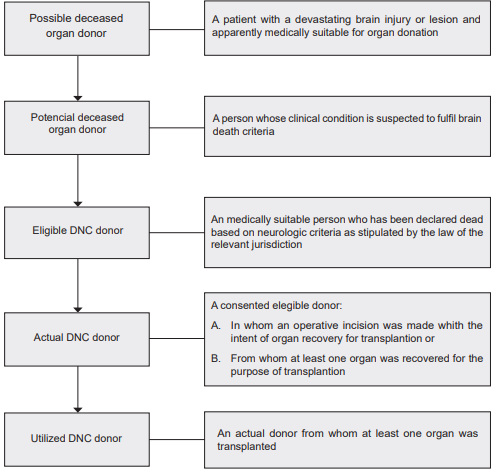

The path through which an individual identified as high-risk for mortality progresses from notification within the Transplant Network until they transform into a utilized organ donor is termed the Critical pathway of deceased donation. While certain steps within this pathway can exhibit variation among countries, its fundamental structure remains consistent. This pathway begins at medical institutions where there is a patient with a poor neurological prognosis (Glasgow Coma Score of 5 or less) that must be reported to the Transplant network through one of its regional dependencies (CRT). Regardless of the patient’s diagnosis or underlying health conditions, once this reporting occurs, the individual is classified as a potential organ donor. Then, based on a medical assessment, the patient may be excluded from the route if his neurological condition improves or remains unchanged without deterioration. Additionally, exclusion can occur if the patient possesses a condition rendering them unsuitable for donation, such as active non-exceptional neoplasia, multiorgan failure, advanced age, or multiple comorbidities. Some possible organ donors die from circulatory criteria, not meeting the death from neurological criteria, thus being discarded as organ donors.

The sequence of stages that facilitate the journey from a deceased individual to a fruitful transplant has been designated by the WHO as the “Critical Pathway for Deceased Donation” 9 as shown in Figure 1. This pathway or protocol aims to establish a tool for evaluating donors, identifying critical improvement points, and reducing the loss of donors/organs. The pathway begins by including patients at high risk of death, and excluding individuals unsuitable for donation. As a result, less than 40% of the people who enter the pathway end up being actual organ donor. Here we describe the findings of the critical pathway for deceased donation in regions of Colombia (called Regionals or CRT - for Coordinación Regional de Trasplantes) 10, describing the population of possible DD evaluated by Fundonar Colombia, an Organ Procurement Organization (OPO) in 2022.

Methods

Study design

This study is an analytical observational investigation of a historical cohort, focusing on alerts for potential donors assessed by Fundonar Colombia’s operational coordinators from January 1 to December 31, 2022. The study analyzes demographic characteristics, reported causes of death, contraindications during donation, and organ extraction success for transplantation.

Variables and definitions

The critical donation pathway spans from potential donor alerts to effective donors. Alerts are triggered by patients with a Glasgow score of ≤ 5. Potential donors have severe brain injuries deemed medically viable for organ donation. They include suspected brain-dead patients, while eligible donors are officially declared brain-dead. Current donors undergo surgery to salvage organs or retrieve them for transplantation. Effective donors are current donors whose organs have been successfully transplanted. Contraindication reasons are exposed in Table 1.

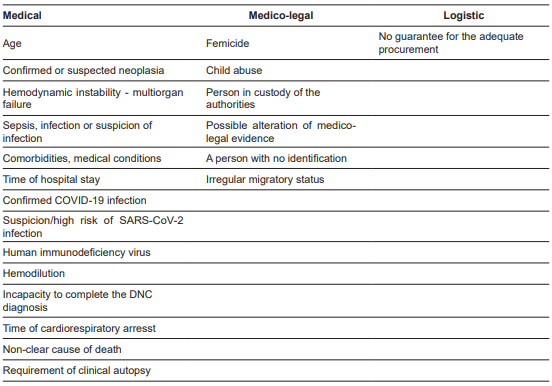

Table 1. Causes of contraindication of possible/potential deceased organ donors in three regions in Colombia.

Collection techniques

A thorough retrospective review was carried out on information documented in Fundonar’s databases regarding 1451 potential organ donor alerts that were reported to the National Transplant Network across different regions. These alerts were evaluated in three main cities (Bogota, Medellin, and Barranquilla) by the operational transplant coordinating physicians in the year 2022.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive examination of the variables was carried out. Categorical variables were presented as absolute and relative frequencies, while quantitative variables were assessed for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Based on their distribution, quantitative variables were expressed using measures of central tendency (mean and median) and dispersion (standard deviation and interquartile range). To compare eligible and ineligible candidates, the Chi-squared test was used for categorical variables, and the Mann-Whitney test was employed for quantitative variables. All analyses were performed using R Studio version 4.2.2.

Results

Possible organ donors’ characterization

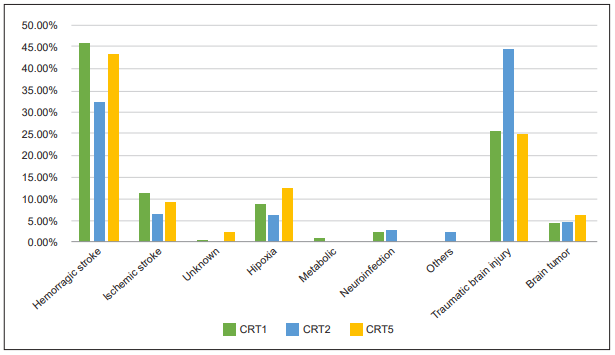

A total of 1451 potential deceased donors were assessed across 24 cities in three regions of Colombia (CRT1, CRT2, CRT5) during the year 2022, all of whom entered the Critical Pathway for Deceased Donation. The distribution was 694 in CRT1, 433 in CRT2, and 324 in CRT5. Among these donors, 61.9% were male, and the mean age was 46.3 years (SD 19.3). CRT1 accounted for the largest proportion of potential donors at 47.8%. The primary diagnoses observed in donors were hemorrhagic stroke, making up 41.3% of the overall potential organ donors, followed by traumatic brain injury (TBI) at 31.1%, and ischemic stroke at 9.5%.

The critical pathway

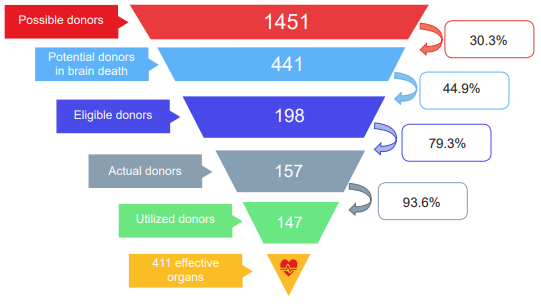

In our study, 224 individuals (15.4%) of the potential organ donors were not considered for the donation process due to either neurological improvement or a stable medical condition. Consequently, 41.7% (606) were ruled out for medical or legal reasons before being declared DNC. Also, 12.4% presented DCC, with no possibility of organ donation. Thus, from the original 1451 only 441 (30.3%) were diagnosed with DNC, constituting the potential organ donors pool. Out of the total, 136 were excluded as organ donors due to medical, legal, or logistical reasons. Among these, 107 instances lacked legal authorization due to family non-consent or absence of presumed consent procedures. In 138 cases, families consented to organ donation, while 60 instances utilized legal presumption, leading to 198 eligible donors. Out of these potential donors, 147 became actual donors (contributing at least one transplanted organ), with 98 from CRT1, 44 from CRT2, and 5 from CRT5. The distribution of POD through the CP is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Critical Pathway within a cohort of kidney transplant deceased donors in three regions in Colombia during 2022.

Causes of neurological deterioration

Effective donors were younger than POD at 42.5 years, and 61.9% were male. The main difference is noted between CRT1 and CRT2 regarding the main cause, hemorrhagic stroke for the former and TBI in the latter. The main causes of neurological impairment that led to the reporting of potential donors were hemorrhagic stroke (559 patients, 38.5%) and traumatic brain injury (451 patients, 31%). The reasons for contraindication were categorized as “medical”, such as sepsis, hemodynamic instability, multiorgan failure, and presence of neoplasms; “medico-legal” when the cause and/or mechanism of death were subject to legal investigation and the extraction of anatomical components would compromise evidence; and “logistical” when situations arose where it was not possible to ensure the care of the potential donor, for example, when they were in hard-to-reach municipalities. Figure 3 shows the distribution of POD neurological impairment.

Figure 3. Causes of neurological deterioration that led to reporting to the transplant network in three regions from Colombia.

Comparison among regions

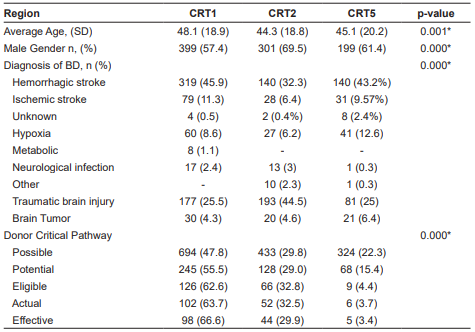

Disparities across various regions were meticulously analyzed, revealing distinct variations in the mean age distribution of donors across CRT1, CRT5, and CRT2. Donor demographics within CRT1 exhibited a higher mean age (48.1 years), closely shadowed by CRT5 (45.1 years), followed by CRT2 with an average of 44.3 years. Conversely, CRT2 demonstrated a conspicuous preponderance of male donors, constituting a substantial 69.5% of the total donor cohort. Within CRT5, this proportion equaled 61.4%, while CRT1 relatively diminished the proportion of male donors (57.4%). Shifting our focus to the domain of cerebral death diagnoses, each region showcased distinct prevalence rates. CRT1 showed the highest occurrence, mainly associated with hemorrhagic strokes, making up a significant 45.9%, followed by TBI at 25.5%, and ischemic strokes at 11.3%. In contrast, CRT2 revealed a heightened frequency of traumatic cranial events (TBI), constituting 44.5%, closely followed by hemorrhagic strokes at 32.3% and ischemic strokes at 6.4%. In the context of CRT5, hemorrhagic strokes emerged as the predominant diagnosis, followed by TBI at 25% and subsequently instances of hypoxia at 12.6%. Upon delving into the critical donor pathway categorization, a salient observation surfaced: CRT1 contributed significantly to most donors, encompassing the entire spectrum from initiation to culmination of the process. However, it is imperative to underscore that a substantial subset of donors encounters exclusion at the inception of the process within the confines of the CRT5 region. All the results were statistically significant. Table 2 presents a region comparison.

Discussion

This study unveils the outcomes of the critical pathway for deceased donation in three regions of Colombia. We scrutinized 1451 potential donors; nevertheless, merely 147 translated into actual donors. In the group of 1451 evaluated POD, 441 (30.3%) were diagnosed with brain death. Among the potential donors following brain death, 198 (44.9%) met the criteria as eligible donors (medically suitable). From this subset, 157 donors (79.3%) proceeded to become actual donors (undergoing surgical incisions for organ retrieval), and among them, 147 (93,6 %) had at least one organ successfully recovered (actual donors with organ recovery). In the end, a total of 411 organs were utilized.

An essential factor that determines the dynamic of organ donation-transplantation is the medical suitability of the donor 11. However, there is no universal definition of the suitability of an organ donor, and selection criteria differ from organ to organ with the same donor 12. Although there is an accepted but outdated concept of an ideal organ donor (an otherwise healthy, young person who meets the criteria for DNC, with little or no vasoactive support and normal labs), the proportion of transplants performed with organs from those ideal donors is decreasing every year due to many factors, namely, the aging population, better neurocritical protocols that produce a reduction in the number of patients with cranioencephalic trauma that reaches DNC, a larger proportion on non-communicable chronic diseases in younger population like diabetes and hypertension 13,14. On top of that, there’s a lack of information on the general characteristics of the population of donors, the reasons for exclusion, and the ratio of donors obtained from each donor 15.

A recent paradigm proposed by the WHO calls for self-sufficiency in organ transplantation, reducing the risk of cross-border transplantation, a better control over the transplants performed, and a reduction in the mortality and morbidity of the national population 9. However, this is a complex goal to achieve, given a series of factors involved in the process. The critical pathway highlights critical points at which the potential donor pool reduces the number of donor candidates and allows the organizations to propose interventions that can potentially increase the donor rate. Consistent with previous literature, our results reveal disparities in the distribution of donors based on their region of origin 16,17.

We present the CP of deceased organ donation in three regions of Colombia during 2022, in which it is observed that from the original 1451 possible organ donors reported to the Transplant Network, only 147 (10.1%) were actual donors. One significant area of reduction in organ donation occurs during the assessment process by transplant coordinators. This is because not all patients meet the criteria for brain death or experience a positive neurological outcome, leading to some patients deviating from the established protocol or remaining in a state of poor neurological function without progressing to irreversible loss of brain function 18. A significant number of patients may not be aware of their neurological condition, and they may have medical issues that make them ineligible for organ donation. This includes individuals with active cancer, inadequate blood flow, poorly managed infections, and those whose cause of death requires investigation by government authorities. The second point of reduction is when the potential donor (a patient with a confirmed diagnosis of DNC) is declared as a real donor because of family consent or legal presumption. Although Colombia is a country with an opt-out system, there is agreement between the transplant groups that the conformity of the family with the process is of vital importance to carrying out the retrieval surgery, based on the principle that a donation process cannot be harmful physically or emotionally to the persons involved 19,20.

These two points constitute the limiting step for organ donation, given the fact that some of the contraindications are relative according to the experience and indications of the transplant group as well as the current regulations that allow (or not) the use of donors with conditions like active infections or neoplasms 12. Karan et al. describe a model that assesses the economic benefit of using organs from donors with increased risk of blood-borne virus transmission, like Hepatitis B or C virus, augmenting the donor pool and usage, increasing theoretically 7% the donation rate in New South Wales, Australia 21. Even though it is desirable that the majority of donors meet standard criteria donors, the changes in the population like the aging population, increase in the prevalence of chronic non-communicable diseases 13,14, as well as reducing rates of head trauma and better protocols for the attention of neurocritical patients, has made a shift in the ratio of standard vs extended criteria donor, pushing forward the use of those and considering every day more indications for organ donation 8.

Our study has certain limitations, such as potential information bias inherent in retrospective research. Additionally, handling extensive datasets could introduce missing data or measurement errors. To address this concern, researchers diligently reviewed the information and standardized variables to ensure data quality. Cases with incomplete information were excluded to prevent any impact on the statistical analysis.

Conversely, the strengths of this study are notable, particularly in terms of the study population’s size, making it the largest investigation published in our country to date. Moreover, the inclusion of data from regions that conduct the majority of kidney transplants in the country enhances its strength. Therefore, it can be regarded as a nationally representative cohort.

The increasing prevalence of end-stage organ diseases suitable for transplantation is a pressing public health concern 22. Despite the WHO’s call for self-sufficiency policies, achieving this remains challenging due to insufficient donor characteristics information. This study presents the deceased donation process in a Colombian cohort, offering insights into organ procurement and pinpointing intervention opportunities to enhance donation rates.

Conclusion

The constant increase of end-stage organ diseases that are susceptible to transplantation is a public health problem that has been addressed in several ways. The WHO has made a call for the countries to develop policies that enable self-sufficiency in transplantation. However, we are far from that goal. One of the main problems is the lack of consolidated information about the baseline characteristics of the donor pool. This study reports the critical pathway for deceased donation in a cohort of POD in three regions of Colombia. A methodical, structured, and comprehensive strategy for the organ donation-transplantation process, as outlined here, facilitates gaining insights and understanding of the organ donation and procurement process. It emphasizes crucial points where intervention is possible, enabling the identification of areas for improvement in order to enhance organ donation rates.