Introduction

An announcement made by the WHO on January 30, 2020 declared COVID-19 a global health emergency due to the exponential growth of cases in China and other countries of the world, 1 leaving to millions of infections and deaths world-wide it is not only a potential danger to physical health, but an immeasurable threat to mental health due to multiple changes in social interactions. This panorama of uncertainty has been even more devastating for certain populations previously identified to have greater prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress such as medical students.2) (3

There is strong evidence showing a high prevalence of men tal health problems among medical students. A meta-analysis of 69 studies comprising 40 348 medical students showed that the global prevalence rate of anxiety among medical students was 33.8%.4 Similarly, a systematic review and meta-analysis (including 43 countries, 167 cross-sectional, and 16 longitudi nal studies) found that the overall prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms was 27.2%.2 During the COVID-19 pan-demic, these numbers could have been exacerbated due to the drastic change that the pandemic has brought into the educational setting of medical students, therefore it is necessary to broaden our understanding of this problem. Recently, a study with Iranian medical students found a high prevalence of anxiety and depression who were exposed to COVID-19-infected patients,5 and medical students in Jordan showed a potential effect of COVID-19 on emotional distress.6 There are still no reports on the emotional situation of medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic in a Latin American context.

By the other hand, insufficient sleep is a common issue in medical students.7 Some factors such as having no pleasure and entertainment, stress, caffeine, feeling sadness, alco hol drinking, amount of sleeping hours, smoking, a noisy or light bedroom, and substance abuse were related to different sleep disorders.8),(9 Additionally, excessive daytime sleepiness is common among medical students and is significantly asso ciated with psychological distress.10 These data are of greater importance given the current COVID-19 pandemic and the restrictive measures imposed by governments as well as distance education, which could be further deteriorating the sleep of medical students. Therefore, it is important to measure the quality of sleep and its association or impact with mental health in the context of online education.

Given that there is limited research on the mental and psychological impacts of the current COVID-19 pandemic on medical students, the purpose of this study is to examine the associations between mood disorders and sleep quality on medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Design and study population

An analytical cross-sectional study was performed on medi cal students from the Peruvian Union University, Lima, Peru. In this University, 481 medical students from the 1st to 7th academic year were registered in the year 2020.

To estimate the sample sizes required for this study, we used the equation n = NZ2P (1 -P)/d2(N -1) + Z2P (1 - P), where n = 481, P = .50 and d = .05. The minimum sample size for our study was 214 participants. To estimate the possibility of participant dropout, we used the calculation of n + (n x 10%) = 236. For the selection of study subjects, the students who took psychotropic medication, coffee, energy drinks, or those who did not fill out the questionnaire correctly were excluded. Only students who matriculated in the academic year 2020, those who had correctly filled out the questionnaire, and those who signed the informed consent were included. Therefore, the final sample was made up of 310 participants.

Data collecting

An online survey (Google forms) was distributed through medi cal students' WhatsApp groups, by the class presidents of each group. A representative of the research explained the main objectives in online classes and invited the students to partic ipate in the study in December of 2020.

The present study was approved by the Peruvian Union University's ethical committee (2021-CEUPeU-0054). The Informed consent was given by all students; this part was the first option to start the online survey.

Instrument and measurements

The Spanish version of The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used to evaluated Sleep Quality (SQ) in this study.11) This is a self-report instrument of 19 items that estimates SQ and its alterations for one month. The items are divided into 7 components, subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. Each item has a scale from 0 to 3 so the sum of those scores composes the global score, which has a range from 0 to 21. PSQI showed a high internal homogeneity (Cronbach's a=.83), moderate correlation coefficient (Pearson's R, .46 to .85), and score >5 presented high diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity, 89.6%; specificity, 86.5%) to identify a person with bad SQ.12 This questionnaire has shown adequate internal consistency in other studies in the Peruvian population.13 We stratified the population as good SQ (PSQI score <5) and bad SQ(>5) for the analysis.

The other questionnaire included was a Spanish validated version of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) to evaluate mood disorders.14 This scale has a total of 21 questions in a Likert-type format, each item with a score from 0 to 3. Also, it has 3 subscales: depression, anxiety, and stress; each one has 7 items and is scored separately from the other, in which a greater score suggests a greater negative emotional state. The scores for depression, anxiety, and stress were calculated by summing the scores of each subscale and then classified as mild, moderate, severe, and very severe. This scale has also shown an acceptable internal consistency in other studies.15

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using the R program ver sion 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria; http://www.R-project.org). Categorical and continuous vari ables were described as frequencies or mean ± standard deviation (SD). For comparative analysis, x2 or Mann-Whitney U test were performed between SQgroups. To assess the independent association of mood disorders (stress, anxiety, and depression) to SQ, the prevalence ratios (PR) and their respec tive 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were determined using Poisson regression models with robust variance. The analysis was stratified by sex and adjusted for potential confounders, and a P< .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 shows the general characteristics of participants: 310 medical students from Peru -193 (62.3%) women and 117 (37.7%) men- with a mean age of 21.6 ± 3 years old. Students in the early university years (first, second, and third year of study) constituted the majority of the study group. The student location of origin was 52.9% from the coast, 21% from the sierra, and6.1%from the jungle of Peru; a20% was foreign. The sleep characteristics showed that students usually sleep after midnight (51.3%), wake up between 6:00 and 8:00 AM (66.8%), and sleep a total of 6 to 8 hours per day (59.4%). Other sleep characteristics such as snores, coughs while sleeping, or taking sleeping pills presented low frequency. The SQ perceived by students was good in 52.9%; however, the SQ measured by PSQI was bad in 83.9%.

Table 1 General characteristics of population.

| Variables | Overall (n = 310) | Men (n = 117) | Women (n =193) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 21.6 ± 3 | 21.6±3.0 | 21.5 ± 2.9 | .63 |

| Location oforigin | ||||

| Coast | 164 (52.9) | 64 (54.7) | 100 (51.8) | .531 |

| Sierra | 65 (21.0) | 25 (21.4) | 40 (20.7) | |

| Jungle | 19 (6.1) | 9 (7.7) | 10 (5.2) | |

| Foreing | 62 (20.0) | 19 (16.2) | 43 (22.3) | |

| Snoring or coughing a | ||||

| Never | 231 (74.5) | 82 (70.1) | 149 (77.2) | .258 |

| < 1 time per week | 40 (12.9) | 16 (13.7) | 24 (12.4) | |

| 1 a 2 times per week | 23 (7.4) | 13 (11.1) | 10 (5.2) | |

| >3 times per week | 16 (5.2) | 6 (5.1) | 10 (5.2) | |

| Sleeping medication a | ||||

| Never | 248 (80.0) | 94 (80.3) | 154 (79.8) | .279 |

| < 1 time per week | 33 (10.6) | 15 (12.8) | 18 (9.3) | |

| 1 a 2 times per week | 17(5.5) | 3 (2.6) | 14 (7.3) | |

| > 3 times per week | 12 (3.9) | 5 (4.3) | 7 (3.6) | |

| Time to sleep a | ||||

| Before 10 PM | 15 (4.8) | 4 (3.4) | 11 (5.7) | .64 |

| 10:00-11:59 PM | 136 (43.9) | 51 (43.6) | 85 (44.0) | |

| After 11:59 PM | 159 (51.3) | 62 (53.0) | 97 (50.3) | |

| Time to get up a | ||||

| Before 6:00 AM | 77 (24.8) | 25 (21.4) | 52 (26.9) | .519 |

| 6:00-8:00 AM | 207 (66.8) | 81 (69.2) | 126 (65.3) | |

| After 8:00 AM | 26 (8.4) | 11 (9.4) | 15 (7.8) | |

| Hours ofsleep a | ||||

| < 6 hours | 112 (36.1) | 35 (29.9) | 77 (39.9) | .058 |

| 6-8 hours | 184 (59.4) | 79 (67.5) | 105 (54.4) | |

| >8 hours | 14 (4.5) | 3 (2.6) | 11 (5.7) | |

| Perceived sleep quality a | ||||

| Good | 164 (52.9) | 67 (57.3) | 97 (50.3) | .28 |

| Bad | 146 (47.1) | 50 (42.7) | 96 (49.7) | |

| Measured sleep quality a | ||||

| Good | 50 (16.1) | 20 (17.1) | 30 (15.5) | .841 |

| Bad | 260 (83.9) | 97 (82.9) | 163 (84.5) | |

| Data expressed as mean±SD or n (%). a Last month. | ||||

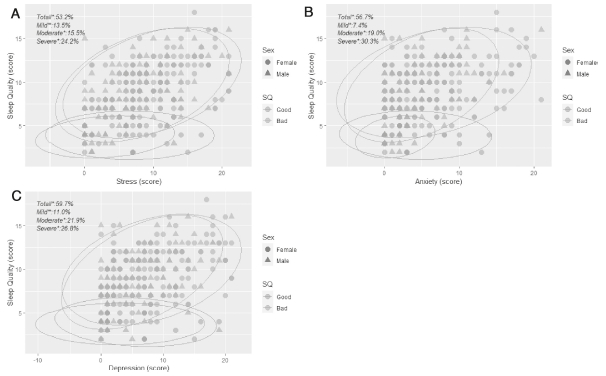

Table 2 shows a comparative analysis of sleep quality by sex. Sleep after midnight and sleep less than 6 hours per day were significant patterns in both sexes. We found significant differences in the frequency of those students who perceived good SQ when it was really bad in both sexes. On the other hand, age presented significant statistically in women (23.2 vs 21.2 years old) but no in men in the SQ groups. Concerning mood disorders, anxiety (56.7%), stress (53.2%), and depression (59.7%), these were highly prevalent among the medical students with predominance in the bad SQgroup in both sexes (figure 1). Male students presented a significant prevalence of all mood disorders in the bad SQ group, while in women only the anxiety and stress were significant in comparative analysis.

Table 2 Sleep quality groups and mood disorders of medical students, by sex.

| Variables | Men | P | Women | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good SQ (n=20) | Bad SQ (n = 97) | Good SQ(n=30) | Bad SQ(n=163) | |||

| Age (years) | 21.8 ± 2.4 | 21.6±3.2 | .418 | 23.2±3.5 | 21.2±2.7 | .001* |

| Time to sleep a | ||||||

| Before 10 PM | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | < .001* | 7 (63.6) | 4 (36.4) | <.001* |

| 10-12 PM | 15 (29.4) | 36 (70.6) | 23 (27.0) | 62 (73.0) | ||

| After 12 PM | 2 (3.2) | 60 (96.8) | 0 | 97 (100) | ||

| Hours of sleep a (%) | ||||||

| < 6 hours | 0 | 35 (100) | .001* | 0 | 77 (100) | <.001* |

| 6-8 hours | 18 (22.8) | 61 (77.2) | 23 (21.9) | 82 (78.1) | ||

| >8 hours | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 7 (63.6) | 4 (36.4) | ||

| Perceived sleep quality a | ||||||

| Good | 19 (28.4) | 48 (71.6) | < .001* | 29 (29.9) | 68 (70.1) | <.001* |

| Bad | 1 (2.0) | 49 (98.0) | 1 (1.0) | 95 (99.0) | ||

| Anxiety | ||||||

| No-anxiety | 18 (29.5) | 43 (70.5) | .001* | 18 (24.7) | 55 (75.3) | .024* |

| Mild-moderate | 1 (3.3) | 29 (96.7) | 5 (9.6) | 47 (90.4) | ||

| Severe | 1 (3.8) | 25 (96.2) | 7 (10.3) | 61 (89.7) | ||

| Stress | ||||||

| No-stress | 18 (28.6) | 45 (71.4) | .001* | 18 (22.0) | 64 (68.0) | .036* |

| Mild-moderate | 1 (3.0) | 32 (97.0) | 9 (15.8) | 48 (84.2) | ||

| Severe | 1 (4.8) | 20 (95.2) | 3 (5.6) | 51 (94.4) | ||

| Depression | ||||||

| No-depression | 15 (27.3) | 40 (72.7) | .027* | 14 (20.0) | 56 (80.0) | .102 |

| Mild-moderate | 23 (8.3) | 33 (91.7) | 12 (11.1) | 54 (88.9) | ||

| Severe | 2 (7.7) | 24 (92.3) | 4(7.0) | 53 (93.0) | ||

|

SQ: sleep quality. a Last month. * P< .05, statistically significant. Data expressed as mean ± SD or n (%). | ||||||

Table 3 shows the Poisson regression analysis between mood disorders and SQ stratified by sex. In male students, the bivariate analysis showed that all mild-moderate and severe mood disorders, increasing the prevalence of bad SQ com pared to normal mood; however, in the multivariable analysis only stress (PRa = 1.30; 95%CI, 1.08-1.57; P< .01) and anxiety (PRa = 1.34; 95%CI, 1.09-1.56; P<.01) increased the prevalence of bad SQ. Women presented a similar pattern in the bivariate analysis compared to men; while in the multivariate analysis only severe stress (PRa = 1.15; 95%CI, 1.01-1.29; P< .05) increased the prevalence of bad sleep quality.

Table 3 Association between emotional state and quality of sleep stratified by sex

| Mood disorder | PRca | 95%CI | P | PRab | 95%CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | ||||||

| Stress | ||||||

| No-stress | 1 | reference | - | 1 | reference | - |

| Mild-moderate | 1.36 | (1.15-1.61) | < .001* | 1.29 | (1.10-1.52) | .002* |

| Severe | 1.33 | (1.11-1.60) | .002* | 1.30 | (1.08-1.57) | .005* |

| Anxiety | ||||||

| No-anxiety | 1 | reference | - | 1 | reference | - |

| Mild-moderate | 1.36 | (1.15-1.64) | < .001* | 1.31 | (1.13-1.59) | .001* |

| Severe | 1.37 | (1.14-1.63) | .001* | 1.34 | (1.09-1.56) | .003* |

| Depression | ||||||

| No-depression | 1 | reference | - | 1 | reference | - |

| Mild-moderate | 1.26 | (1.04-1.52) | .017* | 1.22 | (0.99-1.50) | .051 |

| Severe | 1.27 | (1.04-1.54) | .018* | 1.21 | (0.98-1.49) | .063 |

| Women | ||||||

| Stress | ||||||

| No-stress | 1 | reference | - | 1 | reference | - |

| Mild-moderate | 1.07 | (0.92-1.26) | .374 | 1.04 | (0.89-1.22) | .582 |

| Severe | 1.20 | (1.05-1.37) | .005* | 1.15 | (1.01-1.29) | .029* |

| Anxiety | ||||||

| No-anxiety | 1 | reference | - | 1 | reference | - |

| Mild-moderate | 1.20 | (1.03-1.41) | .022* | 1.22 | (0.97-1.30) | .121 |

| Severe | 1.19 | (1.02-1.39) | .027* | 1.09 | (0.94-1.26) | .233 |

| Depression | ||||||

| No-depression | 1 | reference | - | 1 | reference | - |

| Mild-moderate | 1.02 | (0.87-1.20) | .819 | 1.00 | (0.86-1.17) | .967 |

Discussion

In the current context of a pandemic, it is important to pay attention to the mental health and SQof future health professionals, such as medical students. Various studies show that medical students score high on validated rating scales that measure emotional distress, mental illness, sleep disorders and poor quality of sleep.8),(16),(17

In this study, the results obtained after observing the impact of quarantine due to COVID-19 on quality of sleep of human medicine students revealed that 83.9% of students have poor SQ despite that 52% perceived that it has good quality. Studies in similar populations and pandemics show high prevalence of poor sleep quality with 72.5% in medical students from Tunisia.18 On the other hand, a meta-analysis of 57 studies found a mean prevalence of 52.7% in medical stu dents, lower than reported, but Latin America being one of the populations with the highest prevalence.19 The results of our work are in accordance with the reality found in other studies in Latin America.20

Pre-pandemic studies in similar populations in Peru and Colombia revealed that medical students already had poor sleep quality (77.6% and 79.9% respectively).21)-(23 The increase in the prevalence of this condition could be explained by the events of the pandemic, such as the order to stay at home, online learning, prohibition of outdoor activities, updates of COVID-19 in all the media, the abrupt changes in lifestyle, deprivation of direct interaction with laboratories in universities and health centers to be able to exercise the essential practices for their professional training.18

In both sexes, lying down to sleep after midnight and reporting less than 6 hours of sleep a day was significant in the group with poor sleep quality. Similar to other reports, med ical students had an average sleep time of 5 to 6 hours.24),(25) Although the recommendation for sleeping time is 7 to 9 hours,26 research on the quality and quantity of sleep (<7 hours) shows that having a negative relationship on aca-demic performance27 resulted in cardiovascular diseases risk factors such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension and all-cause mortality.28)-(31 Sleep is essential for comprehensive learning and memory consolidation, our results expand the knowledge in the literature on the quantity and quality of sleep in medical students.

Figure 1 Distribution of mood and sleep quality (SQ). A: stress score plot (*stress categories in overall). B: anxiety score plot (*anxiety categories in overall). C: depression score plot (*depression categories in overall).

Regarding mood disorders (anxiety, stress and depression), it was found that they were highly prevalent among medi cal students with a predominance in the group of poor sleep quality in both sexes. In male students, bivariate analysis showed that all mild-moderate and severe mood disorders increase the prevalence of poor sleep quality compared to nor mal mood. However, in the multivariate analysis only stress and anxiety increased the prevalence of poor sleep quality. Interestingly, women presented a similar pattern to men in the bivariate analysis, while in the multivariate analysis, only severe stress increased the prevalence of poor sleep quality. This could be because female sensitivity to stress could be explained by the role of sex steroids in regulating mood.32

High levels of stress and lack of sleep can cause various mental or physical health problems, such as depression, memory impairment, decreased motivation, obesity, as well as sedentary behavior including medical students, who are under high academic pressure and generally have a short duration of sleep to meet academic demands.33 Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has produced unprecedented changes in the pace of life of a medical student, generating significant stress and concerns about health, social isolation, distance studies, fear of contagion, etc.34 These factors could be influencing moderate to severe stress participants in this study, who showed significantly up to 1.3 times poor sleep quality in the model adjusted for age, years of education and place of origin.

It is critical that the Institutional Academic Counseling Center focuses on students' study skills and copes with their stressful environment. Also, it is best to educate medical students about proper sleep hygiene and the consequences of poor sleep hygiene practices.

One of the limitations of this study is the absence of a study of our population before the COVID-19 pandemic, to observe how much was the precise increase in poor sleep quality due to the pandemic. In addition, all data collected are self-reported and this could make them not completely reliable.

Conclusions

This study allows us to observe the consequences of the COVID-19 on medical students from Peru, and that they are a vulnerable population to poor SQ and bad mood, which in the future will have an impact on health. This study should be extended to more populations, it will allow the implementation of specific measures related to an adequate scheduling of study hours, rest periods and promoting good sleep hygiene in future doctors