PYD, conceptualisation and salient paradigms

Positive Youth Development (PYD) characterises youth based on their capabilities and resources (Balaguer et al., 2022). This notion diverts from the traditional approach focusing on young people´s misconduct (Catalano et al., 2004). In its place, the PYD theory advocates positive developmental outcomes that enable a successful transition into adulthood, especially for those aged 18 to 29. This period has been coined emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2000) and is defined by changes, exploration, and preparation for adulthood.

In the literature, typical PYD paradigms comprise key competence or assets, which have been traditionally integrated into the developmental systems theory (Ford & Lerner, 1992). This paradigm posits that human developmental processes result from converging biological, psychological, and contextual variables (Molenaar et al., 2014). For instance, Lerner and colleagues primarily envisaged the 5C paradigm, from which two additional competence were added in later developments (Dimitrova et al., 2021; Geldhof et al., 2015; Lerner et al., 2005). Other salient frameworks are the development assets (Benson, 2007; Scales, 2011) and the flourishing model of mental health (Keyes, 2005, 2007). Within these, the Cs and the developmental assets have been consistently implemented in the research design of developmental researchers and broadly cited in the literature (Dimitrova et al., 2021). The Cs model (especially the 5Cs of PYD) has provided greater research evidence (Geldhof et al., 2015) besides being more extensively applied in intervention, especially in North America (Geldhof et al., 2014).

The five competence framework (5Cs)

Bradshaw and Guerra (2008) have stated that the five Cs theory offers a common nosology for researching wellbeing criteria in emerging adults. The construct was originally coined by Little (1993) and subsequently developed by Lerner and colleagues. It comprises four domains: Competence, Confidence, Connection, and Character, to which Caring was appended as the fifth C (Lerner, 2004).

Competence refers to the positive outlook of one’s proficiency in cognitive, academic and vocational arenas, whereas Confidence implies an inner perception of affirmative self-worth (Lerner, 2004; Roth & Brooks- Gunn, 2003). According to Lerner, Connection characterises positive ties with others and bidirectional interchanges between young people and society. Character indicates appreciation for shared norms and reigning culture, the recognition and adoption of social principles, and shared moral/honour codes (Lerner et al., 2005), whilst Caring implies empathy and sympathy for others (Lerner, 2004).

Developmental assets profiling (DAP)

The developmental assets profile (DAP) comprises an extensive set of contextual and individual strengths predicting psychological, academic, social, and health criteria (Benson, 2007), encompassing 40 assets equally clustered into 20 internal (i.e., skills) and 20 external resources (i.e., interpersonal). According to Benson, the profiling depends on the core idea that emerging adults select the assets that present comparative advantages for their own survival and life objectives in their embedded communities. In the current study, only one internal resource from this framework has been consi-dered: Positive Identity. This domain has been conceptualised as “a sense of control and purpose, as well as recognition of own strengths and potentials, including personal power, self-esteem, and positive outlook” (Dimitrova & Wiium, 2021, p. 5).

The flourishing model in youth

The relevance of studying flourishing in young people relies on the fact that at least half of the adult population does not experience severe psychopathology during their lives (Keyes, 2002). Within the PYD literature, distinct scales of wellbeing, symptom checklists, as well as questionnaires depicting life-meaning variables, such as purpose in life or hope, have been mostly considered as outcomes of thriving by scholars in the field (Ryff & Keyes, 1995; Keyes, 2005). Overall, these constructs are key to measuring positive outlook and thriving, among which the measurement of well-being from its tripartite conceptualisation (i.e., physical, social, and psychological) has been the approach that has received more consideration in the literature (Keyes, 2002).

Purpose in life, an insufficiently studied construct in samples from global south

Purpose in Life (PIL) has been defined as “a central, self-organizing life aim that organizes and stimulates goals, manages behaviours, and provides a sense of meaning” (McKnight & Kashdan, 2009, p. 242). The construct has been mostly tested in Canadian and American samples; in which a positive correlation between PIL and identity-related variables, such as positive self-image; and a negative correlation between PIL and propensity for crime was detected (Hill et al., 2016). The results of these investigations have shown that the construct correlates positively to identity development, although scarce investigations with other than North American populations (i.e., Global South developing economies) restrict the generalisability of these results to psychological phenomena (Arnett, 2008; Henrich et al., 2010).

Relevant international PYD findings to the research aims

Abdul Kadir and Rusyda (2022) examined the explanatory function of Positive Identity, Support, Creativity and Thriving on General Well-being as criteria. The authors conducted multiple regression modelling, concluding that these four dimensions explained up to 37% of the variance in General Well-being in Malaysian emerging adults. In these analyses, Positive Identity, an internal asset from the DAP framework, yielded the highest effect size (R2 change = .29), followed by Support (an external asset from the same DAP paradigm, (R2 change = .06), stressing the importance of these core developmental assets on youth well-being. In addition, these authors reported two positive double mediation models. In the first, creativity and thriving partia-lly and positively mediated the effect of Positive Identity on General Well-being. In the second, creativity and thriving partially and positively mediated the effect of Support on General Well-being. Both indirect effects from these developmental assets on General Well-being were similar in effect size. However, the direct effect of Positive Identity on General Well-being had a higher effect size than Support on General Well-being, again revealing the salience of Positive Identity on Flourishing.

Abdul Kadir and Rusyda (2021) reported a moderate positive correlation between PIL and well-being in Malaysian emerging adults. In addition, PIL mediated the influence of both Confidence and Connection on General Well-being. Furthermore, Dervishi et al. (2022) studied Albanian minority populations, reporting that Connection showed the strongest positive correlation with PIL. In contrast, Character and Caring, although both significantly correlated with PIL, showed weaker correlations. In addition, the authors reported that Connection, Character, and participant age significantly predicted PIL and altogether explained 16% of the variance in PIL. It is noteworthy that of the abovementioned three predictors, Connection exhibited the highest effect size.

Relevant PYD findings to the research aims in the Chilean population

There is scant research on the relationship among the study variables with the Chilean population, and especially with PIL. However, previous investigations conducted in Chile with mental health criteria reported that positive identity was directly associated with psychological well-being and had a double indirect effect on this criterion through the Chilean participants’ level of Confidence and Character (Pérez-Díaz, Nuno-Vásquez et al., 2022). In addition, Pérez-Díaz, Bachmann Vera et al. (2022) reported that Positive Identity, Confidence, Character, and Connection explained 64% of general well-being’s variance and 61% of psychological well-being’s variability. In this latter research, significant differences were reported between women and men across all well-being measures (Emotional, Social, Psychological, and Overall), in favour of men. Pérez-Díaz et al. (2025) reported that Positive Identity, Confidence, Character, and Connection significantly predicted PIL in Chilean emergent adults and altogether up to 52% of the variance in PIL.

Neira-Escalona et al. (2024) reported that father’s support and mother’s support (i.e., defined as tangible or external resources), as assessed independently, were positively associated with both academic self-concept and general self-efficacy (i.e., defined as intangible or internal resources) in a large sample of adolescents from Southern Chile, and that in turn, academic self-concept and general self-efficacy reduced future concerns in this population as the criterion. Finally, regarding flourishing assessment, Ibanéz Sepúlveda (2013) has informed that only 6% of the Chilean population reached well-being scores that allow to label them as “flourishing”, which is remarkably low in comparison to the 17% previously informed by Keyes (2002) with lay participants from the United States.

Aims of the study

There is a thrust to fill the gaps in the PYD literature, especially regarding scarcely scrutinised populations such as those from the Global South developing countries (Pereira et al., 2023). Such attempts must be conducted through methodology-wise, comprehensive, and novel examinations across developmental fields. To contextualise, the state of the art in Latin America can still be labelled as emergent and predominantly confined to Chilean, Colombian, Mexican, and Peruvian samples (i.e., Domínguez Espinosa et al., 2021; Manrique-Millones et al., 2021; Pérez-Díaz, Nuno-Vasquez et al., 2022). Thus, the current study complements previous investigations intended to fill the gap in the literature with Chilean participants (Neira-Escalona et al., 2024; Pérez-Díaz & Bachmann Vera et al., 2022; Pérez-Díaz, Nuno-Vasquez et al., 2022), especially by informing on the relevance of Positive Identity and Connection for the PIL of this population. Moreover, identifying specific factors contributing to reducing risky behaviours in Latin American Youth has been affirmed to be essential to the region’s welfare (Manrique-Millones, 2021).

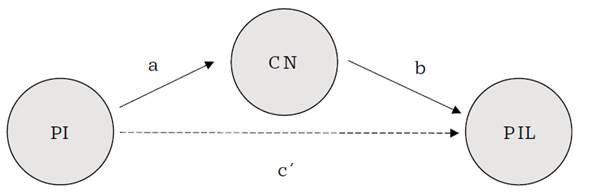

In the present inquiry, a simple mediation theorisation was used to test the following hypotheses: 1) Positive Identity predicts Purpose in Life (H1), and 2) Connection will mediate the relationship between Positive Identity and Purpose in Life (H2); objectives that were tested via Structural Equation Model (SEM). Latin-American populations offer a unique view of the world that needs to be explored, an opportunity that PYD researchers in this region are harnessing to narrow the literature gap and depict indicators of Latin-American youth well-being (Koller & Verma, 2017).

Method

Participants

The cross-sectional study design uses data collected during the initial wave of the CN-PYD (Cross-National Positive Youth Development) project in Chile. The sample comprised 261 emerging adults (nWomen = 189, nMen = 72, MAge = 21.87, SDAge = 3.14). All participants provided their informed consent and were conveniently sampled via online surveying on Qualtrics. Data was collected from April to November 2021. All questionnaires were available through a single link and disseminated by the research team. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), reference Nº 612969. Moreover, the Ethics and Bioethics Committee in Human Research of the Austral University of Chile processed and approved local ethical clearance in Chile. The dataset from the study has been made of open access: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/76nwjf62kk

The developmental assets profile

The Developmental Assets Profile (DAP; Benson, 2007) was utilised to measure the developmental assets. The instrument comprises 58 statements on a 5-point Likert response scale through internal and external assets. The profile has been used in cross-cultural research across distinct populations, covering thousands of teenagers and emerging adults from 9 to 31 years old (see Scales et al., 2017). As for the aims of the present study, only the domain Positive Identity was used, which showed high internal consistency (a = .84).

The short form of the PYD

The PYD Short Form (PYD-SF; Geldhof et al., 2014) assessed the 5Cs. The instrument encompasses 34 statements using a 5-point Likert response scale through the five C dimensions. For the aims of the current study, only Connection was used, which displayed satisfactory internal consistency (a = .74).

Purpose in Life Abbreviated Scale

The abbreviated Purpose in Life in Emerging Adults Scale (PILEA) is a unidimensional questionnaire comprising four Likert-scaled items; its responses range from totally disagree to totally agree (e.g., “There is a direction in my life”, Hill et al., 2016). The questionnaire was reliable in the present sample (a = .81).

Manrique-Millones et al. (2021) adapted the three utilised instruments to Latin American Spanish to confirm language correspondence as one of the advances of the CN-PYD project (Wiium & Dimitrova, 2019), from which minor linguistic adaptations were introduced by the local Chilean PYD team to conform with Chilean idioms.

Data analysis and procedure

Preparatory analyses were performed to assess the data’s suitability for SEM, which included normality and multicollinearity diagnostics. CFA analyses allowed testing of the measurement model across the questionnaires’ dimensions. Direct and indirect effects were tested according to the study’s hypotheses. Hence, the direct correlation between Positive Identity and PIL was preliminarily tested, followed by the assessment of the mediating role of Connection on PIL.

In these analyses, model fit was evaluated by MLR estimations (maximum likelihood with robust standard errors) applying the goodness of fit standards suggested by Hu and Bentler (1999) as to the following indices: RMSEA (i.e., values below .06), Standardised Root Mean Squared Residual, (SRMR) (i.e., values below .05), and CFI/TLI (i.e., values close to or greater than .95). All SEM analyses were executed in R Studio version 2023.12.0.369 with R version 4.3.1 by the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012). Figure 1 illustrates the tested model.

Results

Preparatory analyses

All three measured dimensions showed normal distribution according to normality plots. Preliminary multicollinearity diagnostics determined that multicollinearity between the exogenous variables (i.e., Positive Identity and Connection) was minimal. More specifically, the VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) score between the two exogenous variables was 1.33 (cf. values higher than 5 signify disconcerting multicollinearity, Hair et al., 2011), whilst tolerance was 0.75 (cf. values around zero denote low tolerance and thus high multicollinearity, and conversely, values close to one reveal high tolerance and low multicollinearity, Hair et al., 2014). In summary, tolerance and VIF values reflected no multicollinearity for the exogenous variables examined in the research (Positive Identity, b = 0.59, t = 11.47, Tolerance = 0.75, VIF = 1.33; Connection = b = 0.18, t = 3.40, Tolerance = 0.75, VIF = 1.33). In addition, CFA analyses conducted with the three variables included in the research indicated a good fit from the theory to the data: Positive Identity (x2 = 67.97, df = 14, p < .001, CFI = 0.92, SRMR = 0.05), Connection (x2 = 36.93, df = 9, p < .01, CFI = 0.90, SRMR = 0.05), and Purpose in Life (x2 = 1.47, df = 2, p = 0.48, CFI = 1.0, SRMR = 0.01). However, it is worth noting that good model fit for Connection was only attained after deleting two indicators in the CFA analysis, namely, D30 (i.e., “Teachers at school/university push me to be the best I can be”) and D33 (i.e., “Adults in my town/city/ local community listen to what I have to say”) which exhibited low R2 contribution to the overall construct (i.e., 0.150 and 0.181 respectively), and higher residual variance.

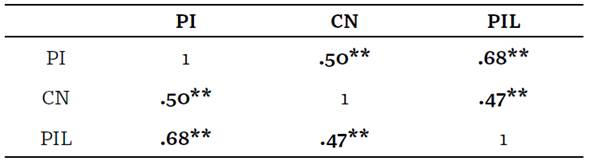

Correlation matrix

Overall, the results revealed a robust positive correlation between Positive Identity and PIL (r = .68), followed by a moderate positive association between Positive Identity and Connection (r = .50) and a low to moderate association between PIL and Connection (r = .47), as presented in the correlation matrix portrayed in Table 1.

Structural equation modelling with mediation analyses

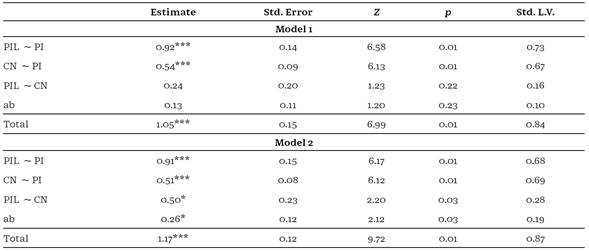

Table 2 displays the model fit statistics of the conducted mediation analyses. The basic depiction of the mediation tested is indicated as Model 1 in the text. Although Model 1 suggested a promising fit, the Connection regression path onto PIL resulted as not statistically significant. Moreover, Positive Identity explained 44% of the variance in Connection and 71% of PIL. Model 2 was appraised after introducing five item correlations from modification indices, all of which were theoretically and linguistically pertinent according to the tested domains (i.e., D33: “My friends care about me”, D34: “I feel my friends are good friends”; D27: “I receive a lot of encouragement at my department/university”; D30: “Teachers at the /department/ university want me to be the best that I can be”; D28: “I am a useful and important member of my family”, D31: “I have lots of good conversation with my parents”; B60: “I think about my purpose in life”, D61: “I feel that my life has a purpose”, E3: “I know which direction I am going to follow in my life” and E4: “My life is guided by a set of clear commitments”).

Table 2 Positive identity and connection on purpose in life modelling

Note. N = 261. x2 = Chi Squared, df = degrees of freedom, CFI = Comparative Fit Index, RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation, RMSEALb = RMSEA Lower bound, RMSEAUb = Upper bound, AIC = Akaike Information Criterion, saBIC= Sample-sized adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion, SRMR = Standardised Root Mean Residual, x2 Δ = Chi-squared changes between tested models. Scaled Chi-Squared Difference Test Satorra-Bentler was implemented. Robust fit test statistics are reported. *** p < .001.

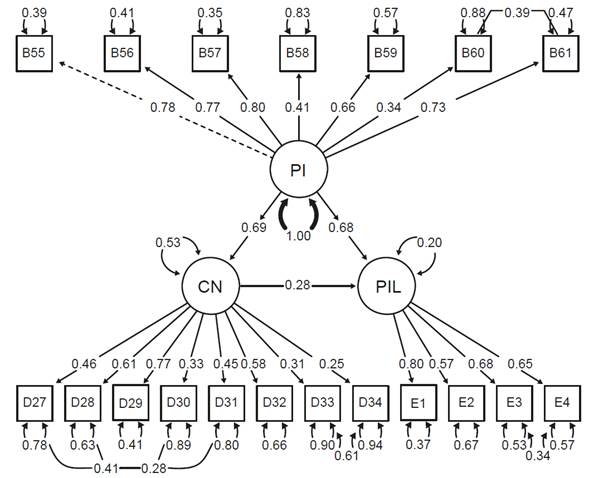

In Model 2, The path “Connection onto Purpose in Life” became statistically significant after item correlatedness was introduced following modification indices, as did the mediation path (i.e., ab, as presented in Table 3). Positive Identity explicated 47.40% of the variance in Connection and 79.60% in PIL in Model 2, which allowed it to reach a “relatively good fit” to data. The progression in model testing is described in Table 3, with full reporting of fit indices and chi-squared variations across the models. Model 2 is the most precise portrayal of the specific structural patterns explored in the examination, which is illustrated in Figure 1. In addition, Table 3 depicts the estimated mediation paths via SEM.

Table 3 Regression coefficients of positive predictors on purpose in life in Chilean youth

Note. N = 261. PIL = Purpose in Life, PI = Positive Identity, CN = Connection. ab = Mediation path from Positive Identity through Connection to Purpose in Life (Indirect Effect), total = Direct effect from Positive Identity to Purpose in Life + Indirect Effect (Mediation), Std. Error = Standardised Error, Z = Z-value, p = p-value, Std. L.V. = Standardised Latent Estimate of the Pathway. 95% CIs are reported. x2 Δ between Model 1 and Model 2 = 136,28***. * p < .05, *** p < .001.

Discussion

The findings stress the necessity and importance of studying Latin-American youth’s PIL, as Chilean emerging adults’ Positive Identity positively explained their PIL (Direct effect), supporting H1. This association was positively mediated by the level of Connection Chilean participants displayed (Indirect effect), consequently backing H2. The direct effect of Positive Identity on PIL yielded the highest effect size, closely followed by the indirect effect of Positive Identity via Connection, and, the direct effect of Connection on PIL, as illustrated in Figure 2. The results are broadly congruent with CN-PYD research in Global South economies (e.g., Abdul Kadir & Rusyda, 2021, 2022; Dervishi et al., 2022; Dimitrova, Fernandes et al., 2021).

Note. PI = Positive Identity, CN = Connection, PIL = Purpose in Life. Indicators from the latent variables are depicted in squares. All reported measures are standardised.

Figure 2 Illustration of the patterns in the final simple mediation model tested in the research

Regarding H1, the study findings echo previous PYD research conducted with young Chilean participants (Pérez-Díaz, Bachmann Vera et al., 2022; Pérez-Díaz, Nuno-Vásquez et al., 2022, Vera-Bachmann et al., 2020) and internationally (Abdul Kadir & Rusyda, 2022, Stabbetorp et al., 2024), in which the effect size of Positive Identity largely surpassed other included predictors, either through SEM or linear regression modelling. It also resembles the reported improvement in social support found in Chilean university students from their first to their second year, and how this increase boosted their eudaimonic well-being (Cobo-Rendón et al., 2020). As for H2, the findings closely resemble those reported by Dervishi et al. (2022) in minority Albanian populations, where a weak to intermediate positive association between PIL and Connection was reported (r = .35). In Dervishi et al. (2022). Connection stood as the strongest predictor of Purpose in Life (b = .38) in a tripartite model, comprising Character and participants’ age, which altogether explained 16% of PIL.

It is worth noting that according to the Identity Capital model, a connected theoretical development from the PYD framework (Côtè & Schwartz, 2002), Positive Identity can be labelled as an intangible resource (i.e., a personality attribute). Instead, Connection would be a tangible resource, as these resources relate to behaviours and possessions, which targets the epitomising role that Connection has in the 5C framework as to the social network in which emergent adults are embedded, interact, and develop. Consequently, the present research blends these resources to explain the variability of the Purpose in the Life of emerging Chilean adults, as these theoretical and empirical enquiries are unusual in the region (Manrique-Millones et al., 2024). The results reveal that high scores in Positive Identity will accompany high scores in Connection (i.e., greater bonding with peers, family, school, and community, Geldhof et al., 2015) and, consequently, in PIL (i.e., a more robust self-organising life aim that conducts one’s own behaviour, McKnight & Kashdan, 2009).

As a word of caution, although cultural invariance of the 7Cs and the general linguistic suitability of the utilised PYD measures to Latin American Spanish for distinct country populations (Manrique-Millones et al., 2021) has been verified; and the factorial structure of these instruments has been properly examined in other regions of the world (e.g., Dimitrova, Fernandes et al., 2021; Tomé et al., 2019), there is still a risk in interpreting a questionnaire without proof that the same domains and their indicators are being measured in each country (Ziegler & Bensch, 2013), which upholds the need for impending PYD inquiries on adaptation, calibration, and validation of the measures utilised in the current study and other related PYD measures in Chilean emerging adults. For instance, in the current dataset, two indicators from the Connection dimension exhibited low factor loadings, which conditioned this preliminary CFA analysis and, subsequently, the tested mediation path. Therefore, properly adapting these instruments supplies a more precise psychological assessment armoury to practitioners in charge of behavioural youth management and promoting a positive outlook and flourishing in emerging adults. In this regard, further psychometric investigations on PYD measures are being conducted by the present study’s first author and associated colleagues across the country as part of the in-progress CN-PYD.

The present study suggests that Positive Identity and Connection act as buffers for Chilean emerging adults by increasing their Purpose in Life to cope with developmental threats typically found in harsh settings for young people. This is consistent with Stabbetorp et al. (2024) who reported a strong and negative association between Positive Identity and worries in Croatian emergent adults, and with Bronk et al.´s (2009) findings, who reported that having a robust Purpose in Life was positively correlated with greater life satisfaction among adolescents, emerging adults, and adults; and that the search for a Purpose in Life was tied to greater satisfaction in life, for the adolescents and the emerging adult groups only. Moreover, it has been documented in longitudinal research that early life adversities were associated with lower scores in Purpose in Life in later life (Hill et al., 2018), and that individuals scoring high on Purpose in Life outlived their average counterparts after controlling for baseline and covariables, such as sex, education level, and retirement status, among others (Hill & Turiano, 2014).

An initial restriction of the study is that causation is unable to be claimed from mediation analyses based on cross-sectional data, given that unknown confounders might be associated with Purpose in Life, impeding the full generalisability of the findings. Nevertheless, well-devised mediation analyses with a strong theory supporting it (as it is in the study hereby provided), especially when the independent variable has been identified as an antecedent (Fairchild & McDaniel, 2017), are capable of reporting reliable evidence of mediation and consequently enhance replication (Agler & De Boeck, 2017). A second limitation concerns the suggested sample size for SEM studies, which should be as high as the parameters included in the mediation tested. For example, Wolf et al. (2013) advocated for an interval of 180 to 450 observations, which was closer to the lower limit in the current research sample.

These findings indicate that tackling Positive Identity may be a more cost-effective intervention to indirectly foster Purpose in Life and Connection in emergent adults. For instance, undergraduate students in universities, usually in the 18-29 age range, can benefit from programmes targeting Positive Identity, which may prevent loss of Connection and Purpose in Life. Upcoming research with Global South samples, and especially with incoming Chilean data, is expected to elucidate with greater precision the unique paths by which Positive Identity and Connection, along with other developmental assets and competence, predict the variability of typical and novel PYD criteria, and their implication for practice.

Conclusions

The findings underpinned a simple partial mediation model, by which participants´ Connection positively mediated the association between Positive Identity and Purpose in Life. The current research advances the understanding of PYD mechanisms on salient criteria, as comprehended and crafted within the Cross-National Project on Positive Youth Development (CN-PYD).1 2