Current literature proposes that stigma and negativity towards sexual and gender minorities is built upon social norms (Habarth, 2014; Worthen, 2021). These norms are termed heteronormativity, a construct that comprises a set of cultural, legal and institutional practices based on the assumptions that there are only two genders that unequivocally reflect the assigned biological sex at birth. These also assume that only sexual attraction between these two “opposite” genders is natural and acceptable (Farvid, 2015; van der Toorn et al., 2020). Ultimately, these norms uphold heterosexuality as the only natural and acceptable sexual orientation, and any sexual- and gender-based behaviour, identity or relationship that escapes this structure is considered a deviation to be rejected or excluded from social life (van der Toorn et al., 2020). In Latin America, studies have predominantly considered heteronormativity from a qualitative point of view. For example, studies in Chile have analysed the impact of heteronormativity on the critical discourse of the student movement (Fiedler, 2017) and on family representations in health services (Vergara, 2020).

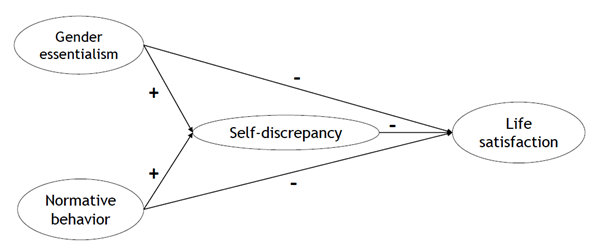

Given its pervasive influence on everyday life, heteronormativity may play a role in individuals’ personal and interpersonal dynamics that can in turn affect their health and well-being. To frame the analysis of these influences, we draw on two tenets of norm-centred stigma theory (Worthen, 2021). Firstly, it states that stigma is culturally dependent on norms. Secondly, that norm following entails privileges, while norm violation entails stigmatisation. These all reinforce social power dynamics (i.e., the intersection of privileged and oppressed identities based, for example, on gender, gender identity and sexual orientation). Yet, as a stigmatised group, LGB people can also uphold heteronormative ideals, which raises the question of the advantages and disadvantages they may experience as a result. Therefore, this study focuses on LGB university students to examine whether their adherence to heteronormativity dimensions is associated with the standards of their socially prescribed self (i.e., self-discrepancy) and, consequently, with their life satisfaction, an indicator of subjective well-being (Figure 1).

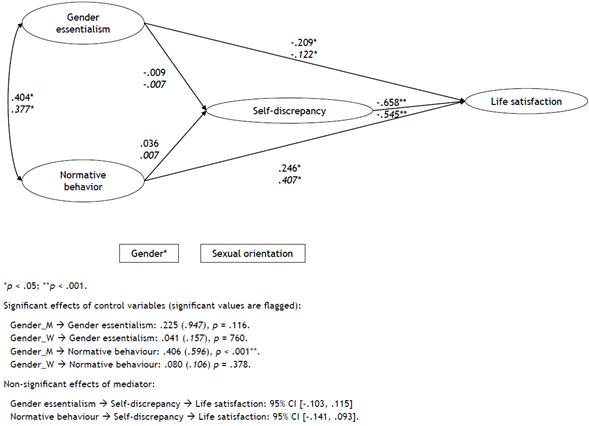

Figure 1 Proposed relationships between the heteronormativity dimensions of gender essentialism and normative behaviour, self-discrepancy, and life satisfaction in a sample of lesbian, gay and bisexual university students.

Heteronormativity permeates psychological processes, and Habarth (2014) conceptualised two interrelated dimensions that reflect how heteronormativity manifests subjectively. The first dimension, gender essentialism, derives from the conception of gender as a dual system determined by biological sex, also framed by binary categories (Scandurra et al., 2021). The second dimension, normative behaviour, involves the consequences of these essentialist beliefs, encapsulating expectations that guide interpersonal relationships based on ideals. For instance, of the complementarity between traditionally masculine and feminine roles (Lasio et al., 2019). Based on this two-dimensional theoretical structure, Habarth (2014)built the heteronormative beliefs and behaviour Scale (HABS). Psychometric studies in Europe (Scandurra et al., 2021) and Latin America (Orellana et al., 2024) provide support to the HABS.

Both heterosexual and sexual minority people can internalise and justify heteronormative assumptions (Habarth, 2014; Jost et al., 2004; Lasio et al., 2019). For instance, a study of Chilean gay men and lesbian women showed that higher system justification decreased psychological distress (Bahamondes et al., 2020). Other studies report that heteronormativity manifests through lower ingroup favouritism in sexual minority individuals compared to heterosexuals. In the former group, heteronormativity can also be linked to agreement with negative beliefs about their group identity, and with upholding relationship expectations based on traditionally masculine and feminine roles (van der Toorn et al., 2020). Research also shows that LGB individuals may reinforce gender expression norms based on dualistic notions (i.e., masculine vs feminine, Lasio et al., 2019); and may adhere to ideas that support the traditional nuclear family (i.e., biological bond, gender complementarity) as the most effective family system (Pollitt et al., 2021).

Studies with LGB samples have positively associated the two HABS dimensions with internalised prejudice, right-wing authoritarianism, religiosity, and negatively with the personality trait of openness to experience (Habarth, Makhoulian et al., 2019; Scandurra et al., 2021). Habarth, Wickham et al. (2019) reported that gender essentialism and normative behaviour are negatively associated with personal growth and purpose in life in lesbian and bisexual women, but not in heterosexual women. Another HABS study reported that sexual minority men with higher heteronormativity showed higher internalised homonegativity (Torres & Rodrigues, 2021). Moreover, Napier et al. (2023) found that desire for “complementary” gender roles in same sex-relationships was positively linked to higher internalised sexual stigma in gay men. Overall, researchers have shown that gender essentialism and normative behaviours can establish distinct relationships with diverse outcomes, but the potential associations of heteronormativity dimensions with subjective well-being indicators require further exploration (Habarth, Makhoulian et al., 2019).

An emerging line of research suggests that sexual orientation is one of many determining factors of life satisfaction. Life satisfaction is the cognitive component of subjective well-being, defined as the global, subjective assessment that a person makes of their life (Diener et al., 1985). LGB individuals consistently report lower subjective well-being compared to heterosexual counterparts (Conlin et al., 2017; Habarth, Wickham et al., 2019; Powdthavee & Wooden, 2015). These differences have been explained by the minority stress model (Meyer, 2003), which stresses that sexual minority individuals face unique challenges and demands that relate to prejudice and discrimination (Meyer, 2003; Wardecker et al., 2019). In this regard, Powdthavee and Wooden (2015)found that sexual orientation is linked to life satisfaction via intermediate variables such as access to employment, health, relationships, and support networks. On their part, Pachankis and Bränström (2018) further showed that life satisfaction in sexual minority individuals may vary based on country-level structural stigma. Other studies show that sexual minority individuals with a negative self-perception of their sexual orientation or who experience higher internalised prejudice report low levels of life satisfaction (Barrientos et al., 2017; Gómez et al., 2022).

As LGB individuals internalise heteronormative beliefs, they may face a discrepancy between who they are and who they perceive they should be. Self-discrepancy is defined as the distance between the individual’s current self, “ideal self” and “ought self” (Higgins, 1987; Philippot et al., 2018). This mismatch between the current and the ideal/ ought self may result in negative emotional states. Specifically, discrepancies with the ought self are associated with increased feelings of anxiety, fear or threat (Mason & Smith, 2017). In university students, self-discrepancy and related indicators (e.g., social comparison) have been negatively associated with life satisfaction (Orellana et al., 2016; Schnettler et al., 2014). Sexual minorities report higher levels of self-discrepancy than heterosexual people (Brunn, 2021), which may be associated with social pressures to conform to heteronormative standards. Likewise, higher self-discrepancy and lower self-acceptance in non-heterosexual, transgender and non-binary people have been linked to poorer health outcomes and lower well-being (Bond, 2015; Camp et al., 2020).

This Study

In Chile, the percentage of adolescents and young adults (aged 15 to 29) who identify as non-heterosexual has increased substantially in the last decade, from 3.4% in 2021 to 12% in 2022 (Instituto Nacional de la Juventud (INJUV), 2022). Young adults are at a life stage known as emerging adulthood, characterised by vital challenges such as gaining autonomy and exploring one’s identity, often in the context of attending university (Arnett, 2000; Barrera-Herrera & Vinet, 2017). Studies in Chile show that as emergent adults try to cope with these demands they are at risk of experiencing mental health difficulties and lower well-being (Barrera-Herrera et al., 2019; Rossi et al., 2019). For LGB emergent adults, these age-related vulnerabilities also come with specific stressors that stem from their membership to a stigmatised group (Worthen, 2021). Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has increased vulnerabilities in these groups (e.g., Gato et al., 2021; Turpin et al., 2023). Young adults can also encounter and reinforce heteronormativity in universities, as heterosexuality is assumed as the standard in curricula, staff and student relationships, and in the configuration of physical and symbolic spaces on campus (Beattie et al., 2021). A study by Clarke (2019) in the United Kingdom showed that heteronormativity is reproduced by both heterosexual and non-heterosexual university students with “anti-prejudice” discourses that ultimately privilege heterosexuality. Other research indicates that heteronormative discourse and practices can affect sexual and gender minority university students’ health and well-being (Ferfolja et al., 2020).

Against this background, the aim of this study was to examine the relationship between heteronormativity and life satisfaction in Chilean LGB university students, both directly and mediated by self-discrepancy. We proposed a partial mediation model, as shown in Figure 1. We hypothesize that the heteronormativity dimensions of gender essentialism and normative behaviour would be negatively related to life satisfaction (Hypotheses 1a and 1b). We also expected that gender essentialism and normative behaviour would be positively related to self-discrepancy (Hypotheses 2a and 2b), and the latter would be negatively associated with life satisfaction (Hypothesis 3). Lastly, we proposed that self-discrepancy would play a mediating role between essentialism and life satisfaction (Hypothesis 4a), and between normative behaviour and life satisfaction (Hypothesis 4b).

Method

Participants

A non-probabilistic sample of 232 university students was recruited in Temuco, Chile. The inclusion criteria were being an undergraduate student enrolled in a university in Temuco, being over 18 years of age, and identifying as lesbian, gay or bisexual (LGB). Participants responded to an online questionnaire. An a priori sample size calculation using Soper’s (2023) online calculator for SEM established a minimum of 137 participants required to obtain an anticipated effect size of .3, with statistical power of .8 and p = .05.

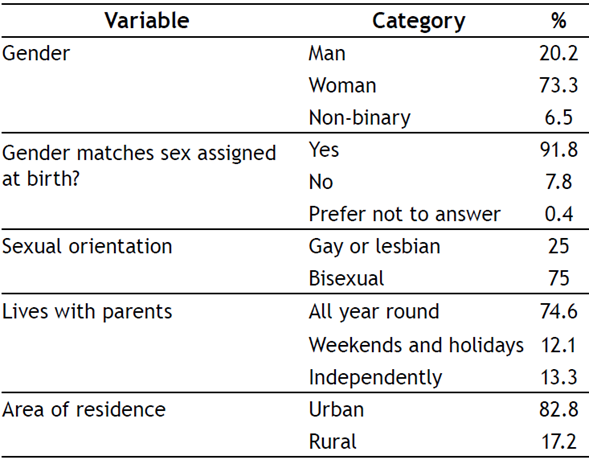

Table 1 displays the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. The sample consisted of 73.3% women, 20.3% men and 6.5% who identified with other genders. Most participants (91.8%) were cisgender. In terms of sexual orientation, 75% of participants were bisexual and the remaining 25% were gay or lesbian. Most participants lived with their parents (74.6%) and in an urban area (82.8%). Their age ranged from 18 to 30 years, with a mean of 20.57 years (SD = 2.35).

Procedure

Data was collected during the first semester of 2021 in Temuco. The link to the online survey was distributed via student mailing lists in four universities, and in social media accounts of LGBT+ groups in the city. The survey was introduced as a study on general university students’ well-being (mailing lists) or LGBT+ students’ well-being (LGBT+ groups). The survey was hosted on the QuestionPro platform. The welcome page of the survey displayed the informed consent which explained the aims of the study, the nature of the questions, and the guarantee of confidentiality and anonymity of the data. Prior to data collection, we conducted a pilot test with 24 participants following the same procedure. These participants met the inclusion criteria previously described. The questionnaire did not require changes and we obtained informed consent from all the participants.

This study is part of a larger research project on sexual orientation and life satisfaction in Chilean university students, supported by the Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID), Fondecyt 3210003. Participants in this study represent a subset of a larger sample that includes heterosexual and non-heterosexual students, whether cisgender, transgender, or non-binary. The Scientific Ethics Committee of the Universidad de La Frontera approved this study.

Measures

Sociodemographic Questionnaire. The first section of this study contained questions about participants’ age, sexual orientation, gender and whether the reported gender matched with the sex assigned at birth, whether they lived with their parents during the year or semester, and area of residence (rural/urban).

Heteronormative Attitudes and Beliefs Scale (Habarth, 2014). This is a 16-item scale with two 8-item subscales: “Sex and gender essentialism” (e.g., “Gender is the same as sex”) and “Normative behaviour” (e.g., “The best way to raise a child is for a mother and father to raise the child together”). Response options range from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. We used the abbreviated version proposed by Orellana et al. (2024) which was translated into Spanish and tested on two samples of Chilean university students, with eight of the 16 items and two 4-item subscales. Based on a fit test of the measurement model we removed two items from the 8-item HABS (items 7 and 9 in the original scale), which improved internal consistency. Two items were reverse-coded, and responses to the six items were summed to obtain the total scores and for each subscale. Habarth (2014) reports α = .92 for the gender essentialism subscale, and a = .78 for the normative behaviour subscale. Orellana et al. (2024) reported α = .73 for the gender essentialism scale and α = .77 for normative behaviour. In this study, reliability was α = .68 and α = .76, respectively. McDonald’s omega values were ω = .72 for gender essentialism and ω = .80 for normative behaviour.

Self-discrepancy - Index (SDI; Halliwell & Dittmar, 2006; Orellana et al., 2016). This index contains seven items referring to the evaluation of the difference between the current and the ought self. Participants were presented the phrase “I ought to be…” applied to intellectual, physical (divided in appearance and performance), social, personal, emotional, and economic dimensions (e.g., “I ought to be: at an intellectual level…”). Responses ranged on a scale from 1 = “just the way I am” to 7 = “very different from the way I am”. Higher scores indicated greater self-discrepancy. Based on a fit test of the measurement model, we removed item 7 (“At the economic level”) given its low factor loads, which improved internal consistency. Orellana et al. (2016)reported this index as a unidimensional factor structure with a reliability of α = .85 in a sample of Chilean university students. In this study, the one-dimensional and six-item SDI had a reliability of α = .73. McDonald’s omega value was ω = .83.

Satisfaction With Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985). This is a five-item scale that evaluates the individual’s global cognitive judgments about their own life (e.g., “In many ways, my life is close to my ideal”). Response options ranged from 1 = totally disagree to 6 = totally agree. All item scores were summed, with higher values indicating greater life satisfaction. We used the Spanish version of this scale by Schnettler et al. (2018), which was tested in Chilean university samples with a reported Cronbach’s alpha of α = .73. In this study, the scale has shown a reliability value of a = .83. McDonald’s omega value was ω = .81.

Analysis Plan

We carried out descriptive analysis using the statistical package for social sciences software (SPSS, v.27). We tested the hypotheses using structural equation models (SEM) with Mplus (v. 7.11). We adopted a confirmatory approach with li-fe satisfaction as the outcome, self-discrepancy as a mediating variable, and gender essentialism and normative behaviour as predictors. A level of statistical significance equal to or less than .05 was considered to reject the null hypothesis. We used the maximum likelihood with robust standard errors (MLR) estimation method. The adjustment was estimated with conventional indicators (Fan & Sivo, 2007; Hu & Bentler, 1999): chi square (p value of X2 > .05), comparative adjustment index (CFI > .95) and Tucker-Lewis TLI index (> .90), fit index based on residuals (SRMR < .08) and comparison error (RMSEA < .06). Lastly, to determine the mediating role of self-discrepancy we conducted a bias-corrected (BC) bootstrap confidence interval analysis using 5000 samples. Mediation effects are considered significant if the 95% confidence interval does not include zero (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

Results

Descriptive Analysis

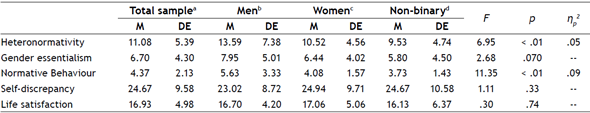

We conducted descriptive analysis for the total sample and comparisons by gender (Table 2) and sexual orientation, which were included as control variables in the model. Men scored significantly higher than women and non-binary participants in heteronormativity, F(2. 229) = 6.95, p < .01, ηp2 = .05, and normative behaviour, F(2. 229) = 11.35, p < .01, ηp2 = .09. We found no statistical differences between women and non-binary people, nor gender differences in gender essentialism, self-discrepancy, and life satisfaction. There were no significant differences between lesbian/gay and bisexual students in the variables of interest (all p > .05).

Table 2 Descriptive statistics for the total sample and by gender

a n = 232. b Sample size n = 47. c Sample size n = 170. d Sample size n = 15

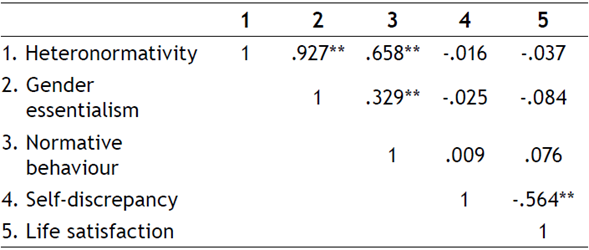

Correlations (Table 3) showed expected positive associations between heteronormativity and its two dimensions. Gender essentialism and normative behaviour also correlated with one another. Self-discrepancy and life satisfaction were negatively associated, while these two variables did not significantly correlate with the heteronormativity measures.

Hypotheses Testing

Prior to running the model, we tested regression assumptions. This analysis showed no missing data nor outliers, and that assumptions of normally distributed random errors, homoscedasticity and linearity, and non-collinearity were met. The assumption of independence of errors was not met.

Figure 2 shows the standardised and unstandardised path results. We introduced gender and sexual orientation as dummy-coded control variables, considering the literature that reports differences in heteronormativity based on these attributes. These variables did not have significant effects on the dependent and mediating variables of the model. However, gender (i.e., being a man vs woman or non-binary) had a significant effect on normative behaviour (β = .406, p < .001). The fit indices of the structural model were adequate: X2 (138) = 189.019 (p < . 002); C FI = .959; TLI = .949; S RMR = .046; R MSEA = .040. Significant factor loadings (p > .05) ranged from .52 to .86 for each indicator. Gender essentialism and normative behaviour showed a significant correlation (r = .40, p < .001).

Figure 2 Standardised and unstandardised (in italics) path results for the relationships between gender essentialism and normative behaviour, self-discrepancy, and life satisfaction. Gender and sexual orientation were dummy-coded and included as control variables. Sexual orientation was non-significant, and results are not reported here. For gender, two dummy variables were coded: Gender_M: 1 = Man and 0 = Woman, Non-Binary, and Gender_W: 1 = Woman, 0 = Man, Non-binary.

The first two-fold hypothesis stated that gender essentialism (H1a) and normative behaviour (H1b) would be negatively related to life satisfaction. Results show direct and significant relationships, but the second one was unexpected. Gender essentialism was negatively related to life satisfaction (β = -.209; p = .003), whereas normative behaviour and life satisfaction were positively related (b = .246; p = .002). These results support Hypothesis 1a but not 1b.

The two-fold Hypothesis 2 proposed that gender essentialism (H2a) and normative behaviour (H2b) were positively associated with self-discrepancy. These hypotheses were not supported; essentialism did not have a significant effect on self-discrepancy (b = -.009, p = .912), nor normative behaviour (β = .036; p = .689).

Hypothesis 3 posed that self-discrepancy would be negatively associated with life satisfaction. This hypothesis was supported as there was a significant and negative relationship between these two variables (b = -.658, p < .001).

Lastly, Hypothesis 4 proposed that self-discrepancy would play a mediating role between gender essentialism and life satisfaction (H4a), and between normative behaviour and life satisfaction (H4b). We found no evidence of this mediating role for gender essentialism (b = .006; p = .913; 95% CI (-0.103, 0.115)) nor for normative behaviour (b = -.024; p = .690, 95% CI (-.141, .093)) and life satisfaction. Hypotheses 4a and 4b were thus not supported.

Conclusions

Lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) people belong to a stigmatised minority group, but they may adhere to heteronormative notions that reinforce negativity towards their own group. We posed the question of the potential effects of holding heteronormative attitudes on perceived self and subjective well-being in LGB university students. Two tenets of norm-centred stigma theory (NCST, Worthen, 2021) provided a theoretical framework for this analysis. Namely, in this study we examined the relationship between the two dimensions of heteronormativity proposed by Habarth (2014), gender essentialism and normative behaviour, and satisfaction with life in LGB university students. We also tested the mediating role of self-discrepancy in these relationships. Results on the associations between heteronormativity dimensions and life satisfaction were mixed, while we found no evidence of mediation. We discuss our findings below.

Non-heterosexual experiences in the realm of sexual and romantic attraction can contradict heteronormative notions, such as that belonging to one gender/sex unequivocally entails attraction to only the “opposite” gender/sex. Thus, as expected, gender essentialism was negatively associated with life satisfaction in LGB university students. This finding aligns with others showing that sexual minority individuals’ internalised homonegativity has a negative effect on their well-being, for example in Dutch and Turkish lesbian and bisexual women (Ummak et al., 2021), gay men in Australia (Morandini et al., 2015), and Chilean adult gay men and lesbian women (Barrientos et al., 2017). Similarly, Napier et al. (2023) showed that internalised sexual stigma is positively linked to gender essentialist preferences in gay men from the United States and the United Kingdom. Notably, expanding on NCST’s second tenet (Worthen, 2021), this finding suggests that certain norm violations (rejecting gender-essentialist notions) can be linked to positive consequences (higher life satisfaction) in the stigmatized group.

On the other hand, we found an unexpected relationship between normative behaviour and life satisfaction: LGB university students with stronger attitudes favouring traditional gender roles in sexual-affective relationships reported higher life satisfaction. This finding contradicts a study that negatively associated normative behaviour with psychological adjustment (Habarth, Makhoulian et al., 2019), as well as research on the effects of stigma on well-being in LGB samples (Barrientos et al., 2017). Nevertheless, our finding draws attention to heteronormativity in sexual minority individuals: for a stigmatised group, following norms that support their stigmatised status (per the NCST) might secure some advantages.

We address three potential -and not mutually exclusive- explanations for the above relationship. Firstly, following system justification theory (Jost et al., 2004), LGB individuals may defend a heteronormative system as it provides structure to crucial aspects of social life (e.g., family life, Pollitt et al., 2021), which in turn reduces feelings of uncertainty and threat (van der Toorn et al., 2020). A second explanation, in keeping with Habarth’s (2014) notion of subjective manifestations of heteronormativity, is the internalisation of cognitive-cultural schemes (Corlett et al., 2022) that promote adherence to normative behaviours in relationships. The social, cultural, and institutional transmission of heteronormative ideals establishes acceptable conceptions and behaviours associated with sexual identity, leading people, regardless of their sexual orientation, to behave following ritualised actions (Boutyline & Soter, 2021). Heteronormativity may therefore offer a cognitive-behavioural structure that helps deal with social uncertainty. Lastly, LGB people sustaining heteronormative principles in romantic relationships may lower their risk of experiencing discrimination. Bahamondes et al. (2020) showed that LGB and transgender individuals who minimised this risk report higher levels of subjective well-being and other indicators of adaptive functioning related to life satisfaction (e.g., social well-being, self-esteem).

Overall, we propose that LGB young adults may endorse some heteronormative beliefs due to socialisation and internalisation: (1) to maintain order and certainty in their social environment; (2) because an alternative system is not conceived as a possibility (Farvid, 2015); (3) or as a mechanism of inclusion and belonging to the normative social context. That is, LGB young adults’ life satisfaction may be more attainable by upholding traditional ideals of masculinity and femininity, of coupledom/families based on complementary roles, or of a compulsory attraction to normative gender expressions (Pollitt et al., 2021). Moreover, within this stigmatised group we find axes of social power, as per NCST’s second tenet. Controlling for gender in normative behaviour showed that LGB men scored higher in heteronormative behaviours than LGB women and non-binary people, meaning that some subgroups with more power would benefit the most from norm following.

Another finding showed a negative relationship between self-discrepancy and life satisfaction. Research reports similar results in university samples (Schnettler et al., 2014; Kwon et al., 2019), while our study examines this relationship in LGB students. However, self-discrepancy did not play a mediating role between the two dimensions of heteronormativity and life satisfaction. Previous studies on mediation between heteronormativity and sexual minority identity have used proximal stressors from the minority stress model, such as internalised homonegativity and rejection expectation (Conlin et al., 2017; Torres & Rodrigues, 2021). Our null finding may be an artifact of measurement, as we assessed a global sense of self-discrepancy composed of indicators that may not be necessarily associated with one another.

This study is not without limitations. The sample was non-probabilistic and thus these results are not generalisable to the LGB university population. Furthermore, the overall low scores on the HABS may deter the detection of effects in the model. Sexual minority individuals tend to have lower HABS scores than heterosexual people (Scandurra et al., 2021; Habart, Wickham et al., 2019), but this scale may not be able to capture specific manifestations of heteronormativity in sexual minority people (e.g., normative behaviours for same-sex couples). A related limitation is the measure of self-discrepancy as a global experience versus distinct dimensions that might be linked to well-being or heteronormativity. For instance, Brunn (2021) found that appearance-related self-discrepancy was negatively associated with life satisfaction. Future studies should consider specific areas of self-discrepancy and expand this exploration to both quantitative (nomothetic) and qualitative (idiographic) measures of self-discrepancy (Philippot et al., 2018).

Lastly, our model did not include moderators, which could help both identify other psychological processes involved in these relationships (e.g., stigma awareness) and provide an intersectional lens (e.g., ethnicity, socioeconomic level). Researchers have used variables such as sexual orientation, gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic level as moderators for the impact of heteronormativity and related constructs (i.e., heterosexism) on sexual minority samples (Habarth, Makhoulian et al., 2019; Pollitt et al., 2021; Torres & Rodrigues, 2021). In our study, nearly 10% of the sample was transgender or non-binary, however due to practical reasons, we analysed normative and non-normative gender identity groups together. Gender identity and other relevant characteristics and identities should also be further considered in theoretical constructions of heteronormativity and its relation to cisnormativity, and the normative assumptions about binary gender assignment and roles. Expanding on the tenets of NCST (Worthen, 2021) will also help identify meaningful moderators of heteronormativity, as this theory advocates for an intersectional lens in the study of norms and stigma.

Nevertheless, our findings carry relevant implications for research and practice. On a theoretical level, the theoretical model that partly underlies this study -norm-centred stigma theory and two of its tenets- has not yet been tested in Chile, to our knowledge, nor in Latin American literature in general; this study suggests avenues to continue exploring the relationship between norms and stigma and its consequences for non-heterosexual, trans and non-binary individuals. This study also poses theoretical questions about the ramifications of heteronormativity and its culture-bound dimensions beyond sexuality and gender. These include subjective well-being, sociodemographic variables (e.g., socioeconomic level), the family domain, political attitudes (e.g., authoritarianism), and intersecting identities. Furthermore, sexual and gender minority emerging adults face specific developmental challenges that often overlap with stigmatisation experiences. Research in these populations would benefit from examining heteronormativity within developmental challenges, self-discrepancy, and subjective well-being.

Lastly, on a practical level, our findings can inform the understanding of norm following/violation dynamics in stigmatised groups (Worthen, 2021) and the consequences for their well-being. University student well-being interventions should examine sexuality and gender norms that configure identities, relationships and spaces on campus, and their advantages and disadvantages for various groups. Larger interventions and policies towards equality in higher education must also account for the ubiquity and multidimensionality of these norms, to counter those that sustain stigma of sexual and gender minorities. Such interventions and policies should aim to foster interpersonal and collective conditions that make sexual orientation a significant contributor to life satisfaction for all individuals1 2.