Introduction

Child-to-parent violence (CPV), defined as a repeated behavior ofphysical, psychological (verbal or non-verbal), or economic violence directed toward parents or guardians (Pereira et al., 2017) is an understudied phenome-non (Cottrell, 2001). Unlike other types of victim-offender relationships, parental relationships are bound by a legal responsibility, meaning that a parent cannot termínate a relationship with their child, even if the child is abusive. Parents may be unwilling to report abuse from a child because either they are skeptical of authorities' ability to take any action, or fearful of the consequences if they do. The situation can be especially complex in cases of underage offenders (Holt, 2016).

Since the 1940s, the relationship between parents and children has been studied by scholars from various perspectives: social learning (Bandura, 1978; Sutherland, 1947), power-control (Hagan, 1989), cultural transmission (Schönpflug, 2008), and cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1984; Bordieu & Passeron, 1977). Sutherland and Bandura assert that an individual's behavior is learned within their first socialization group, and the most frequent, earliest, most intense, preeminent, and longest relationships, as those between parents and children, are the ones that most significantly influence children's criminal behavior. Individuals' learning experiences within their primary socialization group also may influence levels of violence against women and attitudes that demonstrate gender inequality, as Hagan argues in his power-control theory. Sutherland, Bandura, and Hagan's perspective are aligned with Bourdieu's and his colleagues. They define and operationalize the concepts of culture as what is transmitted (e.g., power relationships, knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, behaviors, gender roles, and expectations) and explain its transmission from one generation to the next through the family or any other closely knit social group (Bourdieu, 1984; Boyd & Richerson, 1985; Schönpflug, 2008). When that knowledge is transmitted from one generation to the next, it becomes cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1984). Following Bourdieu's rationale, violence, as part of cultural capital, is intergenerationally transmitted. Within the primary socialization group, violence could take different forms and co-occur between multiple members of the group. The roles of victim or offender could be reciprocal, interchangeable, and transmitted from one generation to the next (Camargo, 2018). For example, exposure to intimate partner violence between one's parents, a type ofchild abuse, predicts violence against women and child abuse in adulthood (Camargo, 2009, 2018; Gage & Silvestre, 2010; Humphreys, Thiara, & Skamballis, 2011; Menon, Cohen, & Temple, 2018; Mitchell et al., 2010; Mitchell, Lewin, Rasmussen, Horn, & Joseph, 2011). Child abuse is also correlated to depression, aggression, delinquency (Morrel, Dubowitz, Kerr, & Black, 2003; Bluestone & Tamis-LeMonda, 1999), psychopathology, and functional impairment (Bayarri, Ezpeleta, & Granero, 2011).

Sense of responsibility, care, discipline, emotional and/or financial support, and affection are critical elements ofparenting. However, there are cultural and generational differences among those who take care ofchildren as well as differences in the ways individual parents or guardians relate to their children. Often, especially in patriarchal cultures, the responsibility of the children's well-being falls on the mother or other female members (e.g., grandmother) of the mother's family (Camargo, 2009).

Gendered parenting and discipline

Parenting and discipline influence children's behavior. Parents are strong transmitters of culture (Schönpflug, 2008). For example, the various tactics to make their children behave in a manner that meets their expectations is transmitted between generations. The variations in parenting are categorized under four types that combine parental responsiveness and the degree of parental demand: authoritarian, authoritative, permissive, and uninvolved (Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2013). Uninvolved parenting includes low levels ofcaring and warmth that may lead to low levels ofsupervision, increasing the chances of the child's engagement in risky behaviors, and consequently, increases the chances of unintentional injury (Keyes et al., 2014). Authoritative parenting includes disciplinary techniques as rewards and is correlated to children's feelings ofbeing loved, accepted, and happy (Barton & Kirtley, 2011; Douglas, 2006; Driscoll, Russell, & Crockett, 2008; Morrel et al., 2003). This style of parenting has been found to prevent adolescent misbehavior (Ruiz-Hernandez, Moral-Zafra, Llor-Esteban, &Jimenez-Barbero, 2019) and callous, unemotional traits in adulthood (Parisette-Sparks & Bufferd, 2017; Schweizer, Olino, Dyson, Laptook, & Klein, 2018). Authoritarian parents are highly controlling and rely on corporal punishment. This type of parenting is linked to maladaptive behavior, the development ofanxiety and depression in children (Asdigian & Straus, 1997; Calzada, Barajas-Gonzalez, Huang, & Brotman, 2017; Douglas & Straus, 2007; Rodríguez, 2003; Seeman et al., 1957), antisocial traits in adulthood (Gamez-Guadix, Straus, Carrobles, Munoz-Rivas, & Almendros, 2010), bullying and aggression at school, and child-to-parent aggression (Calvete et al. 2014; Del Hoyo-Bilbao, Gamez-Guadix, & Calvete, 2018; Gomez-Ortiz, Romera, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2016). In addition, authoritarian maternal parenting is correlated to the mother's mental health (Besemer & Dennison, 2018; Giannotta & Rydell, 2017; Moilanen & Rambo-Hernandez, 2017; Schiff, Pat-Horenczyk, Ziv, & Brom, 2017) and their male partner's level of violent behavior toward them (Newland & Crnic, 2017; Thiara & Humphreys, 2017).

To advance this line ofresearch, this paper uses a cross-cultural sample of Colombian and American freshman-level college students to examine the effects of the cultural transmission as it is illustrated by the correlation between child-to-mother violent or verbally abusive behavior, maternal parenting, and parental domestic violence. Child-to-mother violence, child's personality traits in adulthood, differences by nationality, and the gender of the child were also analyzed.

Child-to-Parent Violence (cpv)

Child-to-parent violence has been identified in up to 22 % of single-parent homes (Armstrong, Cain, Wylie, Muftic, & Bouffard, 2018; Beckmann, Bergmann, Fischer, & Moble, 2017; Contreras, Bustos-Navarrete, & Cano-Lozano, 2019), but it has been underreported and understudied (Simmons, McEwan, Purcell, & Ogloff, 2018; Williams, Tuffin, & Niland, 2017). The existent literature reports that cpv is correlated to domestic violence (Hong, Kral, & Espelage, 2012; Loinaz & De Sousa, 2020; Ulman & Straus, 2000) and is a gendered phenomenon regarding both offending behaviors and victimization. Parental physical aggression toward adolescents predicts adolescents' physical aggression toward their parents (Ibabe & Bentler, 2016; Lyons, Bell, Frechette, & Romano, 2015; Margolin & Baucom, 2014; Wang & Liu, 2013), but no differences by gender of the perpetrator were found when severe physical aggression was directed toward parents (Calvete et al., 2013).

However, both psychological and physical violence against the mother occurred more often than against the father. Additionally, adolescent girls psychologically and physically abuse their mothers more often than their male counterparts (Calvete et al., 2013; Calvete et al., 2014; Lyons et al., 2015), and mothers are more often victims of their children's aggression than fathers (Condry & Miles, 2014; Lyons et al., 2015; Stewart, Jackson, Wilkes, & Mannix, 2006). Not only gender but also race and ethnicity matter regarding aggression toward parents; Caucasian mothers experience more incidents of victimization than their Black and Latino counterparts (Lyons et al., 2015; Walsh & Krienert, 2007). Moreover, the type ofviolence toward one's parent, the gender of the perpetrator, and the gender of the victim are correlated (Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2013; Moulds, Day, Mildred, Miller, & Casey, 2016). Also, sociodemographic characteristics as single-parent, multigenerational household, family size, and family income may moderate the parent-child relationship since they are correlated to abusive behavior toward one's parents (Contreras & Cano, 2014). The severity of a child's maltreatment of their parents is correlated to restraining orders (Purcell, Mullen, & Mullen, 2014),juvenile domestic violence charges (Routt & Anderson, 2011; Snyder & McCurley, 2008), and family violence reports (Buzawa & Hotaling, 2006). Furthermore, child mistreatment could be explained by substance use and abuse (Calvete, Orue, & Gamez-Guadix, 2015).

The current study

A vast body ofempirical evidence has supported the reasoning provided by the learning and differential association theories, stating that an individual's behavior, including violent behavior, is learned (Bandura, 1978; O'Hara, Duchschere, Beck, & Lawrence, 2017; Boyd & Richerson, 1985; Sutherland, 1947); however, less evidence has been provided regarding the generational transmission ofviolence (Bourdieu, 1984; Boyd & Richerson, 1985; Hagan, 1989) and its contribution to a child's abusive behavior toward parents.

To fill that gap in the existent literature, the article has analyzed the potential patterns of the use of violence within the family and the effects of the exposure to violence during childhood as an explanation of the child's violence toward the mother within a cross-cultural sample of adult college freshman students (i.e., American and Colombian). The exploration focuses on the respondents' memories ofexperiences that occurred around the age of 10 regarding maternal disciplinary practices, their mother's irritability and kindness, parental domestic violence, and the children's verbal abuse and physical violence toward their mother. At age 10, most children stül engage in behaviors thatjustify parental disciplinary actions, and most individuals hold accurate memories from that stage of life (Straus & Fauchier, 2007). Patterns of abuse and violence within the family were hypothesized and a causal correlation between experiencing or witnessing violence during childhood and children's violent behavior toward their mother as well as their personality traits in adulthood. Differences in maternal disciplinary practices between Colombian and American mothers were also analyzed.

Method

Participants

The analyzed sample includes 469 freshman college students (182 Americans and 287 Colombians, 58 % women and 42 % men). Most of students (92 % Colombians and 50 % Americans, ages 18-24 years) at the age of10 were living with their biological parents (94 % mother and 81 % father). The sample includes respondents who were single (75 % of Colombian and 40 % Americans), married or living together with their intimate partner (5 % Colombians and 20 % Americans), and had children (7 % Colombians and 36 % Americans). Educational attainment of the respondents' mother includes those who completed high school or less (56 % Colombians, 32 % Americans), attended some college or completed a 4-year college degree (27 % Colombians and 59 % Americans), and attended graduate school (17 % Colombians, 9 % Americans). Regarding race/ethnic identity, 25 % ofAmerican freshman students identified themselves as Hispanic/Latino.

Study design

In 2011, researchers from a variety of fields, universities, and countries were authorized, through a consortium, to use the International Paren-ting Study (ips) questionnaire (an extended version of the Dimensions of Discipline Inventory) to survey college students around the world (Morawska, Filus, Haslam, & Sanders, 2019). This effort facilitated the analysis of individuals' behavior toward their parents regardless of factors as economic development, culture, and religious or political beliefs. The sampling method was based on availability; freshman students who were attending either orientation or the first-day class session of fall 2011 were surveyed at six universities: five Colombian and one American. All but two were public universities, where the majority (86 %) ofthe respondents attended to. Classes or orientation sessions in which questionnaires were distributed were randomly selected in each participating university. All individuals' participation was voluntary and anonymous.

The analysis focuses on the respondents' memories regarding the use of violence in their childhood households when they were around 10 years old.

The questions inquired separately about the respondents' relationships with each parent. However, the focus of this study is the mother-child relationship, maternal parenting, and disciplinary practices and the children's abusive behavior toward their mother. The father's behavior is analyzed only in terms ofhis relationship with the respondent's mother. The respondents' personality traits as they are related to their childhood experiences are also analyzed.

Outcome measures

Child-to-mother abuse may include verbal abuse and/or physical violence; both measures were analyzed.

Child-to-mother verbal abuse

This dimension measures a child's verbal abuse toward their mother at 10 years of age, as a) shouting at; b) insulting; or c) threatening the mother. The answers were codified into dichotomous (Y/N) categories.

Child-to-mother physical violence

This dimension measures a child's physical violence toward their mother at 10 years of age, whether they ever a) slapped or punched; b) hit; or c) kicked or bit their mother. The answers were codified into dichotomous (Y/N) categories.

Predictor measures

All measures but the child's personality traits refer to the child's expe-rience when they were 10 years old. In other words, these dimensions are measured based on the adults' memories of their childhood experiences.

Corporal punishment

This dimension measures the use of corporal punishment by the respondent's mother to discipline them at age 10, whether she ever used a) a shake or grab; b) a spank, slap, smack, or swat; or c) a paddle, hairbrush, belt, or another object. The responses were codified into dichotomous (Y/N) categories.

Severe physical abuse

This is a measurement of maternal severe physical abuse toward her child when they were 10 years old. Respondents were asked iftheir mother ever a) beat you up, that is, hit you over and over as hard as she could; b) hit you on some part of the body besides the bottom with something like a belt, hairbrush, stick, or some other hard object; or c) throw or knock you down. The answers were codified into dichotomous (Y/N) categories.

Deprivation/Penalty

This dimension measures the use of a combination of deprivation of privileges and/or the use of a penalty task assigned by the respondent's mother to make her child behave or comply with her expectations when her

child was 10 years old. Respondents were asked if their mother did any of the following: a) take away your allowance due to misbehavior; b) withhold your toys or other privileges due to misbehavior; c) give you extra chores as a consequence ofmisbehavior; or d) make you do something to make up for misbehaving. The responses were codified into dichotomous (Y/N) categories.

Psychological aggression

This dimension measures a mother's psychological aggression toward her child when they misbehaved when they were 10 years old. The respondents were asked iftheir mother did any ofthe following: a) shout or yell at you; b) make you feel ashamed or guilty; c) hold back affection by acting cold or not giving hugs or kisses; d) call you lazy, sloppy, or thoughtless. The answers were codified into dichotomous (Y/N) categories.

Rewards

This dimension measures a mother's attempt to change her children's behavior at 10 years by rewarding their good behavior. Respondents were asked iftheir mother did any ofthe following: a) praise you for behaving well; b) give you money to stop bad behavior; or c) check on you to be sure that you were doing a goodjob. The answers were codified into dichotomous (Y/N) categories.

Domestic violence (dv) against the father/mother's male partner

This dimension measures the respondents' witnessing, at age 10, their mother's abuse of her male partner. The respondents were asked if their mother did any ofthe following to her male partner: a) insult, swear, shout, or yell; b) push, shove, or slap; c) punch, kick, or beat up. The answers were codified into dichotomous (Y/N) categories.

Domestic violence (dv) against the mother

This dimension measures the respondents' witnessing, at age 10, the abuse oftheir mother by her husband or male partner. The respondents were asked if their father or stepfather did any of the following to their mother: a) insult, swear, shout, or yell; b) push, shove, or slap; c) punch, kick, or beat up. The answers were codified into dichotomous (Y/N) categories.

Mother's irritability

This dimension measures the mother's negative responses to her child's misbehavior at age 10. Respondents were asked if their mother did any of the following when they misbehaved: a) get very angry; b) act on the spur ofthe moment; or c) seem to lose it. Three possible answers were codified: 1) never or almost never; 2) sometimes; 3) usually or always.

Mother's kindness

This dimension measures the mother's positive reaction toward her child's misbehavior at age 10. Respondents were asked if, regardless oftheir mother's discipline, they still: a) felt like she loved you; and b) felt encouraged and supported. They were also asked did she still c) check how your day went at school; or d) play and have fun with you. Three possible answers were codified: 1) never or almost never; 2) sometimes; 3) usually or always.

Child's negative personality traits

This dimension measures the respondent's adult negative personality traits as they are correlated to their mother's parenting. Respondents were asked if during the two previous weeks, they a) desired to beat, injure, or harm someone; b) felt easily annoyed or irritated; c) experienced spells of terror or panic; or d) had temper outbursts they could not control. This variable was codified using three categories: 1) no or very little; 2) moderately; and 3) quite a bit or extremely.

Child's positive personality traits

This dimension measures the respondent's adult positive personality traits as they are correlated to their mother's parenting. Respondents were asked if during the two previous weeks they a) felt calm and relaxed; and b) had been active and vigorous. This variable was codified using three categories: 1) no or very little; 2) moderately; and 3) quite a bit or extremely.

Observed variables

The respondents were asked about their experience at age 10 regarding fairness ofmaternal discipline, maternal responsibility and commitment, and the mother's reaction (irritabüity/kindness) to her children's misbehavior. The effects of the gender and nationality of the respondents also were analyzed.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses were performed. Bivariate distributions were exa-mined for outliers and deviations from normality. Since the analysis included uncommon skewed (Armstrong et al., 2018) behaviors, it was conducted using the Mplus estimator weighted least square mean and variance adjusted (Wlsmv) that does not assume normality (Muthen, 1983, 1984; Muthen & Muthen, 2009). The analysis included a total of 48 variables and was conducted using exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM), which is a combination of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). ESEM fits the data better and results in substantially fewer correlated factors than CFA (Mash et al., 2010; Asparouhow & Muthen, 2008). Three indicators were used to test the model for good fit to the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (Rmsea; Arbuckle, 2006).

Results

Descriptive Analysis

First, for most respondents, their mother looked after them more often than their father did. Sixty-one percent of them said their mother was more responsible for their discipline at age 10 than their father was, while 28 % said their parents shared responsibility equally. When asked about the effects of the use of physical violence to discipline them, 35 % said the effect of their mother's discipline was positive or very positive, and 21 % said that the effect was negative or very negative. Twenty-seven percent said their mother's discipline was hard or too harsh, 56 % said it was fair, and 17 % it was easy or too easy.

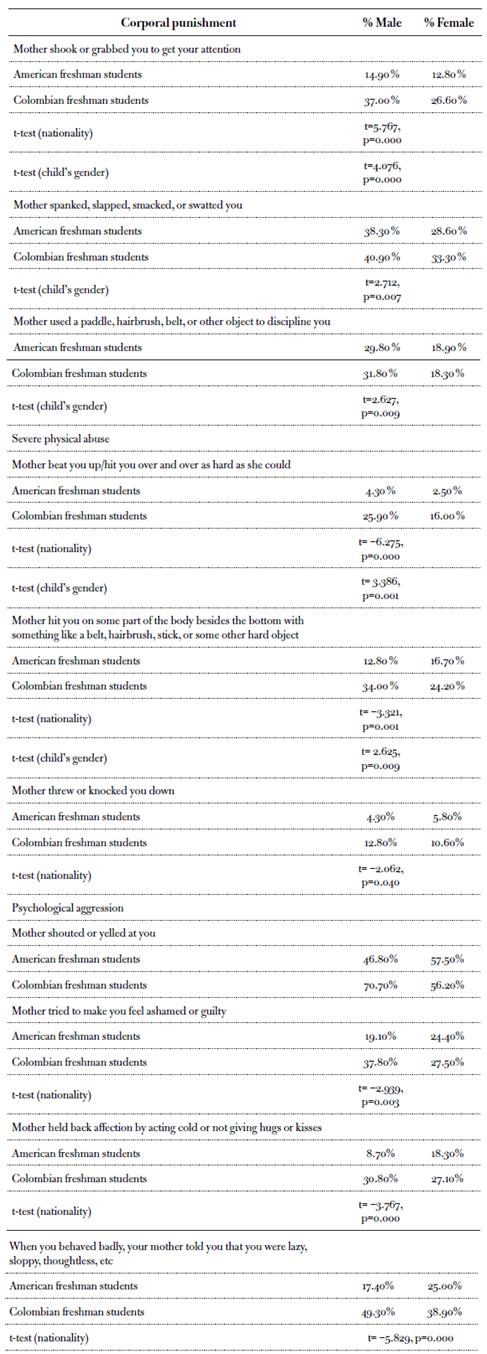

Second, the prevalence ofabusive maternal disciplinary practices and differences by gender and nationality were calculated (see Table 1 for the prevalence ofmaternal abusive disciplinary practices and statistically significant differences by gender and nationality). Colombian mothers use corporal punishment to discipline their children more often than their American counterparts. More males suffered corporal punishment and severe child physical abuse than their female counterparts: Colombians: 24 % and 17 %, respectively; Americans: 7 % and 8 %. In addition, Colombian mothers psychologically abused their children more often than their Americans counterparts: 47 % of Colombian males and 37 % of Colombian females, compared to 23 % ofAmerican males and 31 % of American females. Colombian children verbally abused their mothers more often than their American counterparts: 32 % of Colombian males and 26 % ofColombian females, compared to 22 % ofAmerican males and 20 % of American females, but no differences were found regarding the perpetrator's gender when physical aggression was directed toward parents (see table 1), which is consistent with previous studies (Calvete et al., 2013).

Hypothesized Theoretical Model and ESEM Analysis

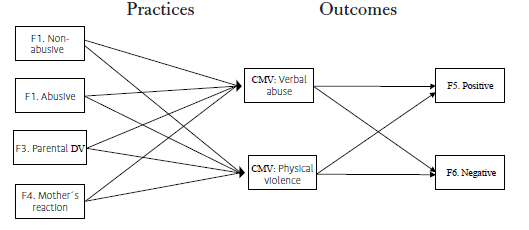

First, the hypothesized theoretical model follows the learning theory rationale (see figure 1); children's behavior is learned from their parents (Bandura, 1978; O'Hara et al., 2017; Sutherland, 1947), and therefore, the correlation between maternal parenting and child-to-mother abuse is causal, as is the correlation between childhood experience and adulthood personality traits. Maternal child abuse and parental domestic violence are correlated and co-occurred as reported by the participants and is consistent with previous research (Herrenkohl, Sousa, Tajima, Herrenkohl, & Moylan, 2008).

Maternal disciplinary practices: F1. Non-abusive maternal disciplinary tacticsdeprivation/penalty (3 items), rewards (4 items).

F2. Abusive maternal disciplinary tacticscorporal punishment (3 items), psychological aggression (3 items), and severe physical abuse (3

F3. Parental domestic violence-against the father/mother's male partner (3 items) and against the mother (3 items).

F4. Mother's reaction toward her child's misbehavior-mother's irritability (3 items) and kindness (4 items).

F5. Child's personality traits-child's negative traits (4 items) and child's positive traits (2 items). Outcomes: Child-to-mother verbal abuse, Child-to-mother physical violence

Fuente: own elaboration.

Figure 1 Hypothesized Theoretical ModelDimensions: Maternal disciplinary Child-to-mother violence Child's personality traits in adulthood

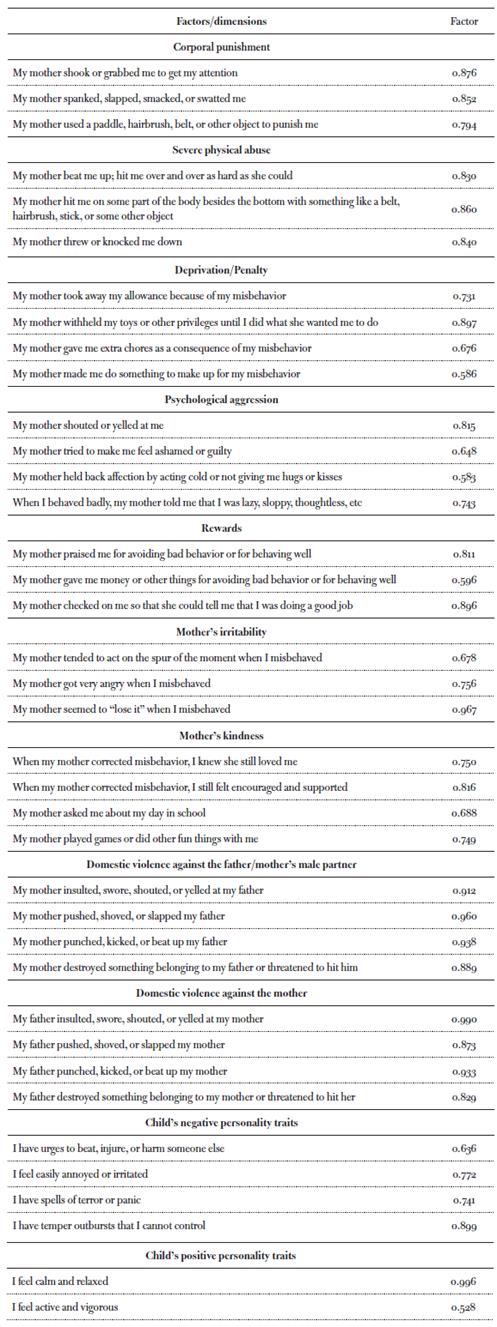

Second, the ESEM analysis resulted in 12 dimensions correlated to the two dimensions ofchild-to-mother abuse (child-to-mother verbal abuse and child-to-mother violence). Six aspects of family conflict were uncovered: a) non-abusive maternal disciplinary tactics-deprivation/penalty (3 items), rewards (4 items); b) abusive maternal disciplinary tactics-corporal punishment (3 items), psychological aggression (3 items), and severe physical child abuse (3 items); c) parental domestic violence-against the father (3 items) and against the mother (3 items); and d) mother's reaction toward her child's misbehavior-mother's irritability (3 items) and kindness (4 items), as well as two dimensions of child's personality traits-child's negative traits (4 items) and child's positive traits (2 items). A two-indicator factor is fine when the sample is greater than 100 (Kelloway, 2015).

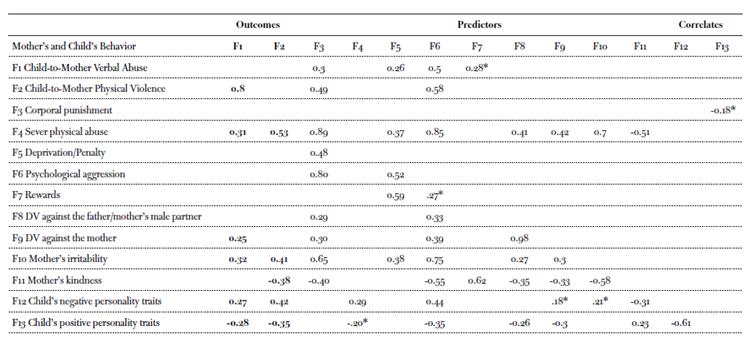

The resulting model fit the data well, as is shown by the indicators of good fit-cFi=0.956, TLI=0.950, Rmsea=0.028, ci (.025, 0.032), Chi-Square=1431.237 (df=1034, p=0.0000)-and the strength of the factor loadings (see table 2). There are also strong and statistically significant correlations between the factors (see table 3). On one hand, child-to-mother verbal abuse and physical violence are highly correlated (.80). Child-to-mother verbal abuse was predicted by corporal punishment (.30), penalty/deprivation (.26), psychological aggression (.50), domestic violence against the mother (.25), the mother's irritability (.32), and child severe physical abuse (.31). It was also directly correlated to child's negative traits (.27) and inversely correlated to child's positive traits (-.28). On the other hand, child-to-mother

Table 2 Factor Loadings

Note: All factor loadings at p=0.000 Chi-square=1431.237(df=1034); p=0.0000 Rmsea=0.028; CI (.025 and .032); CFI=0.956; TLI=0.950

Fuente: own elaboration.

Third, the analysis shows correlations between the dimensions of family conflict.

Table 3 Factor Correlations

Note 1. Statistically significant at p=0.000

Note 2. Statistically significant at p*=0.005

Chi-square=1431.237; p=0.000

Rmsea=0.028; CI (.025 and .032); CFI=0.956; TLI=0.950

Fuente: own elaboration.

Physical violence was predicted by corporal punishment (.49), psycholo-gical aggression (.58), and child severe physical abuse (.53), and correlated to the mother's irritability (.41) and child's negative traits (.42). It was inversely correlated to the mother's kindness (-.38) and child's positive traits (-.35).

Non-abusive maternal disciplinary practices

The use of deprivation of privileges or the imposition of penalty tasks to make children comply with the mother's expected behavior was highly correlated to rewards (.59). It was also correlated to abusive disciplinary practices, that is, corporal punishment (.48), severe child physical abuse (.37), and psychological aggression (.52).

Abusive disciplinary tactics

Corporal punishment was correlated to the use ofpsychological aggression (.80) and severe physical child abuse (.88). It was also correlated to the mother's abusive behavior toward the father/male partner (.29) and the father's abusive behavior toward the mother (.30). The mother's psychological aggression toward her child was correlated to the mother's abusive behavior toward the father/male partner (.33) and the father's abusive behavior toward the mother (.39), as well as her severe physical abuse of her child (.85; see Table 3).

Parental domestic violence. Violence against the father and against the mother were highly correlated (.98). Both domestic violence against the father and against the mother were correlated to the mother's irritability due to her child's misbehavior (.27 and .30, respectively) and severe physical child abuse (.40 and .42, respectively), and inversely correlated to the mother's kindness (-.35 and -.33, respectively).

Mother's reaction to her child's misbehavior. Irritability was correlated to corporal punishment (.65), psychological aggression (.75), severe physical child abuse (.71), and deprivation of privileges or the imposition of penalty tasks (.38). It was inversely correlated to mother's kindness (-.58).

Mother's kindness was correlated to rewards (.62) and the use ofdeprivation or imposition ofpenalty tasks (.59), and inversely correlated to corporal punishment (-.40), severe physical child abuse (-.51), and psychological aggression (-.55).

Fourth, exposure to violence in childhood was correlated to the child's personality traits in adulthood. A child's positive personality traits were inversely correlated to corporal punishment (-.35) and to a child's negative personality traits (-.61). A child's negative personality traits were correlated to the mother's psychological aggression toward her child (.44) and severe child physical abuse (.29), while inversely correlated to mother's kindness (-.31).

Discussion

This study analyzes the relationship between the mothers and their children using a sample of American and Colombian freshman college students, and as hypothesized, it provides support to the cultural trans-mission, learning, differential association, and power-control theories: that is, information in the form of behaviors is passed from one generation to the next. Violent behavior is learned in the family, reinforced by attitudes favorable to that behavior, and transmitted from one generation to the next in the form of cultural capital (Bandura, 1978; Bordieu & Passeron, 1977; Hagan, 1989; Sutherland, 1947). With regard to the theoretical framework, children learn aggressive behavior as they learn any behaviors: from obser-vation or imitation. The term "cultural" applies to a process of nongenetic transmission (Schönpflug, 2008). Children develop "different modeled patterns" and "can evolve new forms ofaggression" (Bandura, 1978, p. 14). These patterns could harm the mother-child relationship since the pain caused by her behavior in the past may have lifelong effects on her child (Thiara & Humphreys, 2017, p. 138). The causal correlation between the mother's abusive parenting, her reaction to her children's misbehavior, and later, the child-to-mother abusive behavior illustrate those effects.

Moreover, Sutherland's differential association theory agrees with Bandura, but goes ftirther by suggesting that individuals' violent behavior is learned through their interaction with other violent individuals, especially those within their primary group of socialization. Violent behavior, Sutherland states, is the result of an equation-type calculus that computes the number ofattitudes favorable to criminal behavior versus those unfavorable to it. In other words, individuals learn violent behavior from others, but that learning process depends on the frequency, duration, priority, and intensity of their relationship with those violent individuals. The mother-child relationship scores high in all of those characteristics: it is experienced on a daily basis, lasts for the child's lifetime, is intense, and takes priority over other relationships with friends or other relatives. Therefore, the common use of violence by the mother (and her male partner), may become a "normal" pattern or way to interact with any or all family members.

Additionally, this study provides empirical evidence for Hagan's power-control theory. Violence and gender inequality are learned within and perpetuated by the family. Often the mother, not the father, becomes responsible for the well-being of the children, regardless of cultural back-ground or nationality. Consistent with previous studies, the present study shows that individuals' behavior is affected by their childhood experiences. Specifically, this study shows that abusive maternal disciplinary practices (e.g., mother-to-child physical abuse and psychological aggression), the mother's reaction toward her child's misbehavior, and domestic violence against the mother by her male partner predict child-to-mother abusive behavior. However, the gender of the child was not statistically significant in the abuse toward the mother, suggesting that both males and females who experienced violence themselves and witnessed violence toward their mother later used violence toward her. This study also demonstrates a differential childrearing treatment by the mother based on her child's gender: physical violence is used more often to discipline boys than girls, which may suggest an effort to reinforce traditional beliefs of strength and masculinity. The respondents' upbringing also predicted their personality traits in adulthood.

This process oflearning by observation and imitation has been discussed by Bordieu and his colleagues. Culture, they argued, applies to traits that are acquired, especially within the family. Those traits are passed from one generation to the next in the form of cultural capital. And cultural capital impacts social structure and power relationships, and may become the basis of exclusion, inequality, male domination, and violence against women (Bourdieu, 1984; Bordieu & Passeron, 1977).

Policy implications

This study provides empirical evidence of different forms of child abuse and violence against women, regardless of the country's level of development. It examines the child's abusive behavior toward the mother, which is a type of violence against women. It also identifies child psychological aggression as the stronger predictor of abuse against the mother. These findings show the need to create or strengthen programs to promote non-abusive disciplinary practices and to promote, protect, and defend a woman's right to live free of violence.

These programs also may be crucial to unveil the multiplicity oftrauma inflicted on individuals during their childhood (Schiff et al., 2017) and may provide a better understanding of the complexity and prevalence of violence in the family and its transmission from one generation to the next. Any programs' design must include institutional readiness (Humphreys, Thiara, & Skamballis, 2011), and organizations and social workers (e.g., family counselors) must be trained to improve their understanding, ability, and willingness to offer a safe environment where changes in the mother-child relationship are seen as a logical step forward. Additionally, since these workers are part of our communities, they must be aware of their implicit bias based on cultural and religious beliefs, and how those biases, contrary to the science-based evidence, could become obstacles themselves to the implementation of the urgently needed changes or the speed with which they can be enacted.

Finally, future research on the transmission of violence must include cross-cultural, multi-country comparisons to better understand the role of culture on child-to-mother violence and its correlation to violence against women, gender inequality, and patriarchal beliefs.