Introduction

This paper focuses on traveler's descriptions and inquisition files, sources that allow us to reread historical documentation and rethink the narrative that represented Africans and their descendants as devils and witches. Given the importance of developing a different perspective about the knowledge of African protection amulets, this paper will discuss African heritage in the New World-emphasizing different parts of America and Africa-and protection amulets used by African population, commonly known as "mandingo bags". This term has become very well-known in Atlantic historiography, especially in what is now Brazil, however, amulets will not be referred to in this way here, since they were not called mandingo bags in the analyzed documents.

It is worth noting that there are no systematic or recurring references to the term "mandinga" in the documentation examined. This is evident in the research carried out by Sweet and Fromont, which indicates that the term bolsas mandingas (mandingo bags) appeared for the first time in archival documents in the 1690s.1 It was not until the eighteenth century that references to the term multiplied, hence the bulk of the researched documentary corpus comes from that century. Moreover, according to Vanicléia Silva Santos, the name bolsa mandinga may have been coined by the inquisitors to refer to the magical practices of Africans being interrogated.

Studies by Vanicléia Silva Santos, Daniela Buono Calainho, James Sweet, among others, have extensively described the context of mandingo bags in the territories that were occupied by Portugal.2 Thanks to the research of Silva Santos, the presence of these cult objects in Brazil has been studied in depth. In her research she analyzed the bags as a recreation of African tradition, considering them a product of the circulation of knowledge between both sides of the ocean and an example of diasporic material culture. Buono Calainho traced the use of these bags in Africa, Portugal, and Brazil, providing a broader perspective of the circulation of these cult objects in the Atlantic context. Sweet's research went beyond the Atlantic Ocean and suggested that the influence of these objects reached as far as India.3 These investigations complement each other and bring together a panorama that transcends the Atlantic and moves into spheres close to a connected history or, at least, beyond the strictly Atlantic.

Now, if we leave the Portuguese Atlantic context and consider the findings from other latitudes, such as Spanish America, can we speak of a history connected to a circulation of African knowledge? This paper asserts that this is possible. According to Carmen Bernand's approach, connected histories imply or need to be immersed in sociability, in contact with the transmission of knowledge, a condition that amulets fulfill.4 We cannot be categorical due to the lack of documentation that would allow the completion of the panorama of the whole of Spanish America, but we can assert that techniques of crafting amulets circulated throughout the population of the African Diaspora.

While it is true that Adriana Maya's and Solange Alberro's research is pioneering in their field, and although they studied people of African origin, they did not explore African cultures from contemporary primary sources written about Africa, its culture, and its people.5 For their part, studies by Pablo Gómez and Cécile Fromont provide an entry point into new narratives that, respectively, address the understanding and circulation of healing knowledge in the African population, and trace amulets in visual culture. Both studies extend beyond the Portuguese context. Gómez studies the circulation of knowledge mainly in the Hispanic Caribbean, while Fromont approaches the French-speaking Caribbean, in addition to studying the Portuguese context.6

For Mexico, one of the first studies that approached this type of research was Sari Meléndez Barrera's thesis, which studied protection amulets.7 Her analysis, based on James Sweet's work, is an extraordinary resource but lacks sources on Africa that could contribute to a more detailed analysis of what was happening in the continent.

This research goes beyond the Portuguese Atlantic. Africa is proposed here as a connected node, and the amulets of protection and their creators as cultural mediators between the four parts of the world. This inheritance not only involves the transposition of African cultural practices and ideologies to the American context but also entails resignification due to a transformation derived from the change of context: from Africa to America.

The documents studied show interrupted or incomplete stories due to their own nature and because there were alternative rhythms and methods of sharing knowledge, very different than those of the literate, Eurocentric, and Catholic elites. However, this will not prevent us from recognizing some of these amulets' characteristics. In this sense, and given the similarities with other types of amulets, these talismans made for and by the African Diaspora served to protect their bodies from the slavery and subjugation that white people exercised over them.

As we will see, while in Brazil, New Spain, and New Granada the Inquisition had a strong influence, in the Caribbean (English, French, and Dutch islands) there were missionaries and travelers who tried to repress the fugitives and their amulets, which explains the use of different sources: inquisitorial cases, on the one hand, and descriptions of travelers and missionaries, on the other.

Where do these protection amulets come from?

In the sixteenth century, the Portuguese were used to carrying portraits of saints, gospel verses, rosary beads, and prayers as protection.8 These amulets were called nóminas. Something very similar could be seen in the representations of people of African origin in the New World, a resemblance that may have gone unnoticed among Europeans. The differences with the amulets of African origin lie in the fact that, according to the earliest sources, they contained parts of the Koran.

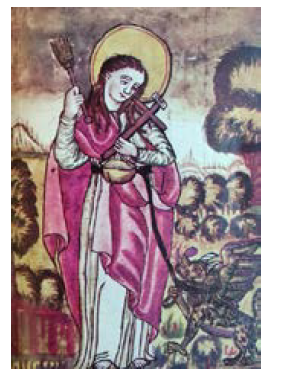

The term nóminas is important here because mention of African amulets can be found in sixteenth and seventeenth-century narratives. However, we cannot forget other names given to these cult objects, for example, bolsas mandingas in the Portuguese context or gri gri, as seen in some representations and stories about Africa (see Figure 1).9

Source: David Boilat, Esquisses sénégalaises: physionomie du pays, peuplades, commerce, religions, passé et avenir, récits et légendes (Paris: P. Bertrand, 1853), plate 20. Courtesy of the National Library of France.

Figure 1 Grand Marabout Toucoulaure, faisant un gri-gri pour une femme.

Descriptions of nóminas in West Africa can be found in Valentim Fernandes' depiction (1506) of the first modern encounters between both worlds (African and European). In his account, Guinean settlers put red square nóminas on their horses' necks every time they went into battle.10 In 1594, Alvarez de Almada referred to the Cazices or Bixirins of Senegambia, people who guarded religious knowledge in the community and manufactured and distributed nóminas that gave much confidence to the population.11 However, it was not until 1606 that a more or less detailed description of the nóminas appeared in a letter to Father Joao Alvarez written by Father Balthazar Barreira. In it, he described how the Cazices deceived people with "nóminas that they make of metal and leather, very well lacquered, in which they put writings full of lies, stating that having these nóminas with them will have nothing do them harm, neither in war nor in peace".12

These lines are complemented by Father Manoel Alvares' description (1607) of the Mandingas as the worst kind of peoples, for they were Moors and deceived others by giving them nóminas that, according to him, were no more than stitched leather reliquaries that they carried around their neck and were made of diverse forms.13 Meanwhile, Sandoval (1627) wrote in Cartagena de Indias that the soniquies (Mandingas):

Also worship superstitious nóminas, very carved, that their infernal ministers have given or sold them: persuading them that by bringing them with them, or taking them to war they will not receive any harm [...]. These teachers (the ministers) teach reading at school and use Arabic script which is the one they write on their nóminas.14

According to Sandoval, the Mandingas communicated with all the kingdoms of Guinea not only to trade gold and salt but with the intention of introducing them to Islam.15 They were able to go from one side to the other because they knew the languages in the area. For Sandoval, it was normal that "Iolofos, Berbesies, Mandingas, and Fulos" understood each other despite the cultural varieties between them, which did not prevent them from propagating and appropriating religion (hence the presence of bexerins among the population).16 According to André Donelha (1625) the Mandingas were the best traders, especially the bexerins, who carried ram's horn amulets and nóminas with written papers that they sold for relics.17 Father André de Faro (1664) wrote that the bags were distributed by the Mandingas and contained papers written with rules, herbs, or pieces of cloth with blood on them.18 And Coelho (1669) described how the inhabitants used leather bags in which they carried papers with writings. These bags were worn next to the body to obtain some type of protection, used by warriors as a defense against enemy weapons, or to protect them from the abuse of the people who enslaved them.19

As observed, since the first contact between Europe and Africa, amulets appeared in several descriptions, remained throughout time, and had their name changed (for example, into the word gri gri). To analyze this phenomenon, we will examine a document from the eighteenth century that compiled most of the definitions mentioned in this paper. In it, Martín Sarmiento devotes a section to the grigrises (Discourse xxi), where he quotes Jean-Baptiste Labat, Alonso de Sandoval, Olfert Dapper, Pierre Vincent de Tartre, and François Froger.20 In his narrative Sarmiento interchangeably calls these amulets grigrises, "billetes" (paper tokens) and nóminas. Quoting Labat, he also mentions that they are cards, papers, parchments, tablets, shells, medals, or sheets inscribed with some words of the Koran, that served as protection against evil spells, witchcraft,21 weapons, diseases, and violent deaths. However, far from being magical, these amulets represented "the apprehension of an Anti-magical preservative," indicating a different and broader view of these objects of worship.22 Similarly, he emphasized the difference between talismans, stating that the gri gris belonged to heretics, while the nóminas belonged to superstitious Christians.23

This description enables us to see why, during the first centuries of African presence in the New World, the possession of amulets was not persecuted or simply went unnoticed. It shows that the perception of amulets changed in the Caribbean, New Spain, and New Granada (since some of the amulets contained Catholic elements, they were considered symbols of Catholic superstitions), and its description of the symbolism of amulets within the West African population indicates that all agreed on the rapprochement of Islam. In all, this variety of conceptualizations enabled the talismans to mutate and avoid inquisitorial surveillance.

This brief reconstruction of the origin of the term also indicates how "ancient" the concept may be, distancing us from the assumption that this inheritance of material culture was exclusive to the eighteenth century. Therefore, focusing on the descriptions-not on the nomenclature-allows to construct a narrative of African cultural heritage against the grain, by inserting them in a discourse closer to known descriptions of Africa. However, this requires acknowledging the fact that documentation outside the Portuguese overseas territories does not refer to amulets as mandingo bags and reiterates the connection with Catholic objects. As we will see, these amulets contained Catholic elements, which can be explained by the incursion of Catholicism into Africa and the instruction of Africans in America.

Consistent with this new reality, the amulets were transformed and, gradually, other external elements were added to the African cosmovision of the time.

In this process, the role of medals and rosaries that the Society of Jesus gave to the baptized slaves and the presence of elements such as papers, as Cécile Fromont mentioned, was essential24 (the bags could contain only papers with prayers or inscriptions, as seen in Figure 1). With this considerations, one discovers a forgotten vein of analysis that has remained almost unexplored in the search for vestiges of African material culture in the New World.

Amulets beyond the Portuguese Atlantic context

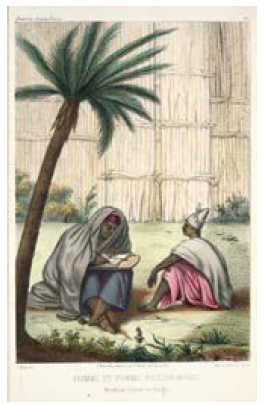

Looking at Figure 2, it can be observed that they amulets, made out of leather or cloth, were worn around the neck or near the body. They were used as protection from stab wounds, shots, illnesses, accidents, and contained an endless number of elements, including hosts,25 cat's eye, sulfur, gunpowder, silver coins, bone of the dead, papers, figures written with black chicken blood and blood from their maker's left arm.26 In general, nóminas could contain different objects according to the requirements of the person who needed one and could have different purposes. While in Africa they were used by warriors as protection against weapons, in America they were used by maroons to protect themselves from white enslavers.

Source: David Boilat, Esquisses sénégalaises: physionomie du pays, peuplades, commerce, religions, passé et avenir, récits et légendes (Paris: P. Bertrand, 1853), plate 17. Courtesy of the National Library of France.

Figure 2 Warrior with amulets on the neck and waist.

Gómez's research shows that this type of amulet existed outside the Portuguese context,27 in the Caribbean occupied by the Hispanic monarchy, a place influenced by African cultures (Gómez not only marks the presence of these amulets in the Inquisition of Cartagena de Indias but also makes a detailed study of the phenomenon). He considers amulets to be part of the knowledge that circulated in the Caribbean and that was used to care for the population. However, the knowledge of amulets was not isolated to this part of the Caribbean, as revealed by Manuel Barcia's investigations.28 In the Conspiracy of La Escalera (1844), for instance, a "sorcerer" called Campuzano Mandinga was accused of preparing and selling amulets to the participants of a plot against the Spanish colonial system.

The Antonio Salinas case is fascinating, as it is the most complete description available of New Granada. He was named in the process as a free black man whose parents were from Guinea, meaning he was an Afro-descendant born in America. When Salinas was arrested by the Inquisition in 1676:

he was carrying a bag around his neck, in which he was carrying white powder wrapped in two small pieces of paper. And in another one a picture of San Diego that seems to have been a cross; a picture of the Holy Christ of Burgos stuck in a piece of crimson taffeta. Further, in another piece of paper was wrapped a small piece of paper to guard against snakes, a kernel of corn and ten small pieces that looked like splinters of sticks and leaves of some tree; a little green cloth bag and inside it a small image of Our Lady of Solitude painted on paper and a sheet of a tin of the same size, formed on it a cross. And in another piece of paper two little breads of St. Nicholas with other pieces that seemed to be the same; an old Holy Crusade bull with the name of the person to whom it belongs neither outside nor inside; a handwritten prayer that begins "Prayer very miraculous and very profitable to the body and soul" and ends "[if it be your will?] Jesus".29

This description offers valuable information to understand these amulets in the Hispanic context, as it describes each of the religious images it contained. This is the case of San Diego and the Christ of Burgos and even an old bull with an inscription alluding to some sort of indulgence.30 It also describes the amulet's purpose: to protect the wearer from snakes. Finally, it shows that it was protected by a handwritten prayer resembling the gri gri (Figure 1), but this time it was not in Arabic, nor did it contain verses of the Koran. Therefore, we are dealing with an amulet that had been nurtured and had mutated in the context of New Granada.

Antonio Salinas explained to the court that he was a descendant of "blacks from Guinea" and had lived in Nicaragua and Guatemala for more than a decade before returning to Cartagena to work as a ritual practitioner. With these information, Gómez proved the circulation of African knowledge and their descendants in the Caribbean. In addition, he added that years before Antonio's encounter with the Holy Office, the Inquisition's examiner had already interrogated him, since witnesses in Cartagena declared that they had seen him survive the impact of "a cannonball" to the chest. In other words, this bag had protected him from a weapon.

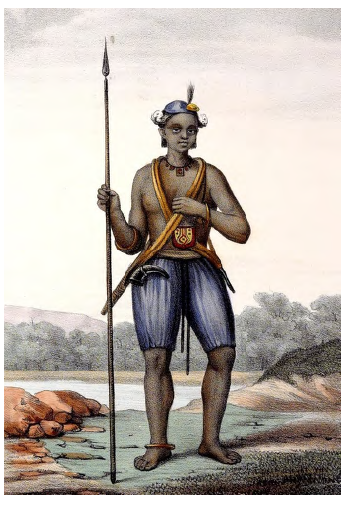

Amulets or Obias in Suriname and beyond

Following this same trail, it is possible to explore other places in the Caribbean and different sources: travelers.31 In Suriname, for example, the existence of protection amulets is mentioned in John Gabriel Stedman's book (1796), where the "famous" Guinean Graman Quacy is depicted as a man known for healing people and selling protection amulets.32 Graman Quacy was described by Stedman as one of the most extraordinary characters of all the "blacks" of Suriname (Figure 3). He gained a reputation in England for his use of a medicine against fever and digestive problems related to parasites, which was manufactured from a plant named after him.33 This made him so popular that his medical knowledge circulated even in Europe and brought him fame and respect. The case of Quancy, however, was not sui generis. These amulets also existed in Haiti (Haitian revolution) and Jamaica (Tacky's Revolt), where they were used by Maroons to become bulletproof.34

Source: John Gabriel Stedman, "Narrative of a Five-Years'", 1796. Courtesy of the Huntington Library and Art Gallery.

Figure 3 The celebrated Graman Quacy.

In his description of Quacy's amulets, Stedman indicates the following: first, that the amulets he made were known as obias (obeas); second, that they were used to become invulnerable, just like the nóminas; third, that they were made of small pebbles, seashells, hair, fish bones, feathers, etc.; and that "the whole fewed up together in small packets, which are tied with a string of cotton round the neck, or some other part to the bodies of his credulous votaries".35 This coincides with the descriptions of the mandingo bags or payrolls that we have seen so far and brings up a geographical topic. According to Martin Sarmiento (who takes up Dapper) the Mohammedans of Madagascar called Ombiasses the people who guarded religious knowledge.36 They were astrologers, acted as doctors and made the nóminas that they called massasserrabes.37

According to Katharine Gerbner, in Jamaica, a priest like George Caries was called obeah-men.38 In her research, black Jamaicans (or Afro-Caribbeans) mixed religion with medicine and superstition, and, in this sense, the concept was similar to Ombiasses in Madagascar. This is another vision of assimilation in African religion, where the denomination Obeah had a positive connotation inside the slave's community and Caries learned this semantic and religious knowledge. In addition to Caries, Gerbner explores the Obi (Obeah) knowledge in Barbados and French Guyana. For Britain's authority, the obeas were not dangerous until Tacky's Revolt, when maroons used this kind of amulets. After that, the British West Indies criminalized obeas and the use of "blood, feathers, parrot beaks, dog teeth, alligator teeth, broken bottles, grave dirt, rum, egg-shells or any other materials relating to the practice of Obeah or Witchcraft".39

It is likely that Ob in the Hebrew Bible has roots in the Arab Obi or Obeah,40 establishing a relationship between East Africa, the English Caribbean, and the descendants of the diaspora. The denomination obias may be a consequence of the transmutation of the word ombiasses, like many words that change over time depending on the place they are used, as happened with malgaches and mangaches. The latter refers to what Don Francisco de Arobe's father has called-from the oil painting Los mulatos de Esmeraldas (1599)-a corruption or deformation of the original name, malgache, which was used to designate slaves that were taken to the region of Lima and, above all, to the northern coast of Peru (Piura). Today their descendants are known as mangache and are believed to have come from Madagascar. Is it possible that this African heritage arrived in the Vicero-yalty of Peru with the manganches? Or, better yet, was there a place where the Ombiasses could be consulted and amulets or remedies requested at the Viceroyalty of Peru?

With this geographical data, one can see the possible connection that these amulets had with Asia, specifically Goa. As Sweet's investigations reveal, Mandingo bags were found in this Portuguese port, which is not surprising, given that East Africa and that part of Asia have always been connected. Furthermore, in the last two accounts the makers are not named mandigueiros, as in territories under Portuguese influence, and it is known that in Brazil and Portugal the origin of the person who made the amulets and the evidence that he or she could provide was highly valued as proof of its effectiveness.

According to the data provided by the website SlaveVoyagesj during the sixteenth century and most of the entire seventeenth century, there were more ship arrivals from Africa than from Brazil to the territories colonized by the Spaniards in America.41 This changed drastically after the flourishing of the sugar business in Brazil and later with the gold boom (something similar happened in the rest of the Caribbean). In other words, the flow of forced migration was affected. This has great significance for our discussion. First, because the Afro-descendant populations in the New World became familiar with the use of protection amulets of African origin due to their place of origin and the contact they had with the people in charge of manufacturing them. Second, because it indicates the extent of these migrations and their directly proportional relationship with the number of arrivals from Africa. This situation partially explains why during the eighteenth century most of these descriptions are found in Brazil and Portugal, while the samples we have in New Granada or New Spain belong to the previous century.

In tandem with our brief historical account of nóminas, Table i indicates that amulets "appeared" in western texts with Valentim Fernandes. In fact, it would be strange not to consider that such amulets arrived in America with enslaved people since 1500. However, it is feasible that the majority of contemporary sources has forgotten, erased, or even ignored this cultural artifact because it was not of particular interest to their authors.

So why did amulets become associated with eighteenth-century Brazil? This remains unknown. However, one can argue that amulets had attracted no attention before. As observed in the historical account, during the first decades of contact between both worlds, there were no references to these amulets, they were unknown, but as the contact and the observation of different customs grew, their presence was noted. In the Hispanic case, all that has been mentioned about the nóminas was materialized by some dispositions of the Inquisition. Between 1640 and 1747, the Holy Office issued sixteen rules, three mandates, and ten warnings with specific indications and prohibitions.42 Rule number eight, for instance, stipulated that crosses or plates used in a superstitious manner were forbidden, a concept not foreign to territories such as New Spain, where stamps, medals, and portraits were expurgated in 1662. This explains how this lists of religious objects went unnoticed by the authorities and how the considerable number of references to them as partial reasons for persecution have not been detected.43 With this in mind, it can be assumed that the use of relics, stamps, or medals was widespread in Hispanic territory.

Beyond the Caribbean, the issue remains uncertain, but some evidence suggests that these amulets could have been present in the Viceroyalty of Peru as well. For example, excavations at the Jesuit Hacienda of Nasca reveal that the descendants of Africans used rosaries (beads)-given to them by the Jesuits once they were baptized-, stamps, and medals.44 The presence of these items in Peru can be compared with the account of the Jesuit Alonso de Sandoval (in Cartagena de Indias, also part of the Viceroyalty), who indicates that the Jesuits gave Catholic symbols as gifts, which were perhaps used as objects of protection:

And it is astonishing to see the great esteem that such savage people have for them, as can be seen in the fact that once the Father who treats them found a black man without an image around his neck, and it seemed that he knew him, and he asked him for it, smiling as he said: He took out a little taffeta bag, and opening it he showed him ten beads in the form of a rosary with which he commended himself to the Lord as best he could, and to finish off he had on it the image that he had put around his neck a year before baptizing him [during] a serious illness; he had already made a pilgrimage through various lands, and yet he had not forgotten those holy beginnings of his conversion.45

In another account, this time of baptisms, Sandoval commented: "They are as happy as if I gave them a treasure, and no doubt they must recognize it in their own way as such, as it really is, since they esteem it so much."46 However, the resignification of religious objects by the African people should not be overlooked. While Sandoval narrates the events as success stories, his anecdotes provide clues about how, from the Catholic perspective, this African cultural practice enabled the objects to go unnoticed before Sandoval's own eyes, just as they remained unseen by other religious actors from the early seventeenth century. This is quite significant because some authors have pointed out that Sandoval's text was almost an anthropological exercise due to the amount of information it contains.47 Nonetheless, as the contents of the bags remained unquestioned, it is possible that his Catholic blindness did not allow him to see beyond the baptisms he was performing, rendering his account insubstantial for understanding the African worldview. Furthermore, religious persecution during these early years of the seventeenth century was concentrated on Jewish practices-which makes sense if we review inquisition cases-. For this reason, "Catholic superstitions" had no major relevance.

Alonso de Sandoval credited his success in converting enslaved people to the fact that they asked and even begged him to baptize them. Since the rite was always accompanied by a medal or rosary, these objects of worship were important to people of African origin. Sandoval's apparent success story is compelling because it probably was part of a rhetoric orchestrated to justify the existence of his book. Furthermore, as Sandoval described it, he presented baptism as if it was going to heal the baptized or protect them from something. What remains unknown is what these supposed pleas were for, given that they were people who had not yet received instruction in Catholicism nor experienced conversion through catechism. This begs the question, what was behind this search for religious images? It is difficult to explain at first, if we consider how Africans saw baptism as a rite of protection48 -for instance, having salt in the mouth was a signal of such protection-. For this reason, Sandoval's stories could also be regarded as suspicious, especially as he describes the urgency of the enslaved to obtain recognition as Catholics. Some even asked for another medal to be bestowed, following which, according to him, they became very happy.49 In addition to these cases, he also wrote about

another black woman, [who] having lost the neck-image, which was placed at her baptism for the effect that we said, walked many days through the town in search of the Father who had baptized her to see if she could find him to give her another one; and not finding him, she went several times to the house where she had been baptized, and her godmother was, to ask for him, until the lady, having found him, sent her to our school with another slave of hers, to give her another medal. And these are not alone, everyone in the middle of the street comes to see the Father, and by signs when the images have fallen, they ask him for others, and follow him, until he has the good sense to enter the first house, and give it to them.50

Given that Sandoval's book describes the presence of nóminas in Africa, why didn't they draw his attention? Was it because he could not understand writings in Arabic and the Koran? Was it because he did not perceive this as a new presentation of an amulet? It is very likely that this lack of understanding explains his description of a successful evangelization of the African population of New Granada rather than a possible indication of their resistance. Besides, his literate, Eurocentric, and Catholic myopia did not allow him to understand that nóminas could be closer to an African- not European-artifact. This must be rethought from a perspective that understands how cultural processes transition, and African knowledge was no exception.

In Peru, two images of Pancho Fierro also draw attention. They depict a water carrier wearing what seems to be a small bag around his neck.51 According to some descriptions, he is dressed in leather and on his chest "there is always the scapular of Our Lady of Carmen, and a leather bag that used to contain the paper token so as not to be taken by the levy, and the money from the daily sale: today it only contains money".52 Based on this description, one could argue, at the risk of being mistaken, that the scapular and the leather bag were reminiscent of the bags that were used as amulets.

Unlike Brazil, this visual evidence is not overwhelming.53 Did Pancho Fierro really paint mandingo bags? We do not know. What we do, however, is that the scapular likely enjoyed great devotion. Then, why use Fierro's wa-tercolors to illustrate this manifestation of African heritage in Peru? Because apart from his work, there is not much more to be found, even if it's clouded with uncertainties. For example, we do not know where the European54 or the indigenous55 begins. These two aspects will be examined later.

Something similar can be seen in the book Buenos Aires negra, where Daniel Schávelzon points out the existence of mandingo bags in La Plata using an image of Hipólito Bacle. In it, two people wear what seem to be amulets, but there is no concluding evidence of the existence of such cult objects other than beads found in archeological excavations.56

Amulets or relics in New Spain

Novo-Hispanic files invite further research into areas that have not yet been considered. For example, several Inquisition documents describe amulets wrapped in bags, such as the case of Felipe Barreto (1713) who brought with him an amulet that enhanced his strength and enabled him to lift heavy weights,57 or the case of Tomás (1707), who carried a small bag with him "so that, even if someone shot him with a blunderbuss [trabuco], they would not hurt him".58

Other Inquisition cases have an amorous character. For example, the file of the mulatto woman Carbo (1629) reads that she hung a root around her neck to be well-loved.59 The woman also argued that this amulet prevented her master from scolding her, which reveals that the amulet had more than one function. The files of Francisca (1620) and Ana (1621) are similar, but in their case, amulets did not protect them from any evil, weapon, or mistreatment.60 The romantic use of amulets was not exclusive to the population of African origin or women. "Whites" also used this type of amulets and referred to the knowledge of African people. This was the case of Sevillian Bartolomé Ruiz (1618), who requested the help of Ana Pinto, a mulatto woman, to cure his "melancholy". As a solution, she offered to make a nómina with many good things to cheer him up and take away the pain. The amulet had to be worn under the shirt, near the heart;61 it had hair, "a cross on top [... ] of yellow silk and the color of the bag was red". Ana also smeared it with water and powder seven or eight times, making crosses, blowing on it and sanctifying it. Cases like this can also be found in Cartagena de Indias, where Paula Eguiluz (1632) asked a lady to bring her husband's whiskers and hair, and later returned them inside a red bag with a-likely copper-coin.62

Inés de Villalobos (1594) was a mulatto woman from Mexico City and neighbor of Veracruz. She was married to Bartolomé García, a carpenter, and used a silk taffeta bag so that her husband would treat her well and never find her with her lover.63 Inés also prayed to Santa Marta at an altar that she had arranged for that purpose (Figures 3 and 4).64

Source: AGN, Mexico City, volumen 206, expediente 9. Courtesy of familysearch.org.

Figure 5 Image of Santa Marta (Black &White).

This watercolor shows the fusion between Catholic/European and African cultures. The painter's skill reveals that the image was probably homemade and the wrinkles in the paper (see Figures 4 and 5) suggest that it was folded and tored in small bags.65 In addition, this aesthetic allows us to approach amulets that were kept hidden.66

Source: AGN, Mexico City, volumen 206, expediente 9. Courtesy of familysearch.org.

Figure 6 Santa Marta's bag.

Like many others, Inés' case began with an accusation: Antonia, a slave of Bartolomé García, saw her performing suspicious rituals. Tomasina, a seven-year-old slave supported this claim, as did Francisca de Villalobos, a 15-year-old, who "exhibits a bag that was given to her so that she kept it for the prisoner".67 Inés was seen with the bag, saying a few words of praise while holding beads in her hands (bag with relics [reliquias], similar to the Portuguese Inquisition, see figure 6). That same bag, according to the file, was also kept by Sebastiana (mulatto girl) who had to "keep it where no one could see it because it had a relic inside".68 The relic was a watercolor of Santa Marta. Inés also kept in a small drawer another image of Santa Marta-painted on animal skin-to which she prayed .69 That is, she had two images: one to pray in the privacy of her house and another that she used as a relic that protected her from her husband.

Source: Archive of Torre do Tombo (ATT), Inquisição de Lisboa, proc. 2355, 1704, fólio 21.

Figure 7 Mandingo bag.

The altar to Santa Marta was beyond the world of the "well-loved". In the Portuguese context, amulets had inscriptions, prayers, crosses, and a series of magical-religious symbols, but here we can appreciate external elements such as the amulet's construction materials (leather and paper) and the prayer itself. It was a relic filled with color and symbology: Inés sought to continue her extramarital relationship with a man called Alonso de la Paz, while subjugating her husband and having a good relationship with him. For this she prayed to Santa Marta so that she would not die in his hands due to her infidelity. This was the main function of her amulet: the relic served to preserve her body's integrity, like other amulets.

The homemade drawing of the virgin shows additional nuances about this case. On the one hand, Inés' devotion to Santa Marta and her eagerness to hide her. And, on the other, the image is presented as if Santa Marta were an allegory of her own act of protection. This is very important because the Mandingo bags were used by slaves to protect themselves from mistreatment by their owners.

Conclusions

This article reveals three previously neglected aspects in the historiography: 1) the importance of African history when dealing with topics about Africans and their descendants in the Americas; 2) that the history of protection amulets is a history that must be seen in a connected way; and 3) that this is a history of long duration that does not belong to a specific era.

To begin with, the study of amulets of the African Diaspora has many nuances. It cannot be understood without considering the origin of amulets in Africa. This allows a fresh approach to the subject. On the one hand, the African Diaspora cannot be studied without anchoring research to African sources, for they provide a more detailed understanding of this population and show us that they were not a "tabula rasa", as sometimes portrayed, or devoid of knowledge, due to their cosmovision and their ancestry. On the other hand, studies of Africa cannot be distanced from studies of its diaspora. This history is part of the history of the continent, and it allows to trace the continuities, circulation, importance, and impact that Africa and its people had on all four parts of the world.

Although amulets were not purely African and included elements of Islamic heritage, their use by people of African origin provided them with protection from the hardships of slavery, mistreatment, and abuse in America, and during violent encounters such as rebellions.

Finally, the amulets of the African Diaspora have existed throughout history. The brief historical account of the first section reveals that these amulets found their way into the West during the sixteenth century, although it is necessary to look beyond the Brazilian space and explore sources of Arab origin. In turn, by studying the presence of Islam in the West and East Africa, it is possible to trace the circulation of these amulets as a function of the diffusion of knowledge. Such a study provides evidence of how amulets arrived in Europe even before the arrival of people of African origin.70 By connecting these stories, a connected macro-history is revealed. It involves different perspectives, heritages, and continuities. Likewise, understanding this process across time enhances our knowledge of these amulets during the nineteenth century, indicating that despite the passage of time they survived, mutated, and continued to circulate.

It is possible that these amulets (Mandinga bags, Obeah, Obias, or relics) share an Islamic origin and were assimilated similarly in East and West Africa. In any case, the map of the diaspora is reflected in this cultural practice (Carabali, Madagascar, Guinea, Angola, and Mandinka). And, despite that there could have been mixtures between them, there is no doubt about their relationship with the African Diaspora and the way in which enslaved and freed people protected themselves from their enemies (husbands, owners, or abusers). This paper has tried to see them as a whole and bring forth the possible relationships between them through the details in their descriptions.