Introduction

Pain is one of the major problems patients experience during hospitalization. This symptom is extremely frequent and varies in intensity according to the underlying pathology. Different studies have indicated that between 10% and 50% of adult hospitalized patients experience moderate to severe pain, and this has a negative impact at different levels.1-3

Acute pain is associated with metabolic, endocrine, and inflammatory changes,4 which may result in increased morbidity and longer hospital stay if not identified and properly controlled. Likewise, pain is associated with psychological changes leading to anxiety, stress, and fear that interfere with daily life activities, particularly in the elderly.5 Increased pain intensity during hospitalization has also been associated with worsening of symptoms, including depression, anxiety, and decreased quality of life.6-8 National studies have reported the consequences of poor in-hospital pain control, including tissue injury that triggers ventilation responses, circulatory, gastrointestinal (GI), and urinary disorders, as well as changes in the metabolism of carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins,9 pro gression to chronic pain, cardiac, respiratory, GI, immune and endocrine disorders.10 Therefore, all efforts aimed at identifying and controlling pain shall be a priority to lessen the negative impact of pain in hospitalized patients.11

On the basis of the above considerations, pain preva lence, intensity, and interference have been used as indicators for quality of care during hospitalization.12-14 These indicators were measured in hospitalized patients at a third-level institution in Bogotá in 2013, and this led to the implementation of strategies aimed at recognizing pain as the fifth vital sign within the "Pain-Free Clinic Policy."15 The purpose of this study is to establish hospital quality indicators (prevalence, intensity, and interference) associated with pain management in adult hospitalized patients, following the implementation of the "Pain-Free Clinic Policy" at a third-level institution.

Materials and methods

Observational, descriptive, cross-sectional trial. Patients over 8 years of age, who had been hospitalized for at least 24hours at a private third-level clinic in Bogotá city from May through September 2015 were included, using consecutive convenience sampling. The exclusion criteria were patients with neurological deficit, patients hospitalized in the ICU, obstetrics, and patients with speech impairment.

Keeping in mind the pain prevalence previously reported (67.5%) at the same institution,15 a 5% accuracy and 95% confidence interval, a sample of 338 patients were included in this trial. To measure pain (prevalence, intensity, and interference), the Brief Pain Inventory -Short Form (BPI-SF) was used.16 In addition, a "big interference" was defined as a score >8 in any of the 7 activities evaluated. The group of surveyors monitored the completion of the survey upon signing the informed consent and collected additional information from the medical record, including age, education, treating depart ment, and analgesia prescribed. The areas of specializa tion were classified into surgical (general surgery, urology, gynecology, trauma, and orthopedics) and nonsurgical (internal medicine, neurology, pulmonology, oncology, hematology, rheumatology, palliative care). Pain manage ment was classified as monotherapy or multimodal, including analgesic techniques in the latter group.

The quantitative variables are reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), as the statistical distribution was not normal. The qualitative variables are described as absolute and relative frequencies. To estimate any gender and type of service differences, the x2 or Fisher test was used, as appropriate, while the Wilcoxon test was used for the qualitative and quantitative variables, respectively. The statistical differences were interpreted as P< 0.05 with 2-tailed hypothesis test. The data were analyzed using Stata 13.0 (StataCorp. Released 2012. Stata for Windows, Version 13. Texas). This study was endorsed by the research ethics committee of Fundación Universitaria Sanitas.

Results

Three hundred thirty-eight participants were included, 125 males (37.0%) and 213 (63.0%) females and their character istics are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the population was 61 years (IQR 47-73 years), with no statistical differences between males and females. The general pain prevalence was 43.4%, with higher levels in the surgical services (47.9%) vs the nonsurgical services (37.5%) (P = 0.05).

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of patients

Median (IQR).

† The differences were estimated using Fisher test.

Source: Authors.

The anatomical site reporting the highest pain levels among the total number of patients was the abdomen (26.2%) followed by head and neck (18.6%), lower limbs (14.5%), and upper limbs (10.3%). The areas with the lowest pain scores were the hip (8.3%), dorsal region (8.3%), lumbar region (6.9%), chest (4.8%), and sacro-gluteal (2.1%).

Women had a higher incidence of upper limb pain (11.0% vs 8.3%), chest (6.4% vs 0%), and head and neck (22.0% vs 8.3%), while men reported pain in the abdominal region (33.3% vs 23.8%), lumbar region (11.1% vs 5.5%), lower limbs (16.6% vs 13.7%), and hip (13.9% vs 6.7%). Pain distribution throughout the anatomical regions in accor dance with the type of service is shown in Fig. 1 (Anatomical localization of pain per treating service).

Pain intensity in accordance with the "current pain" item was 53.8% for mild pain, 31.0% for moderate pain, and 15.2% for severe pain. In terms of the treating service, nonsurgical patients experienced mild pain more often (58.5% vs 51.1%), while moderate pain was more frequent in the surgical services (26.4% vs 33.7%) and severe pain was similar in both services (15.1% vs 15.2%) (P = 0.63).

In accordance with the visual analogue scale, the mean score reported for each pain intensity item was 8 (IQR 6-10) for "the worst pain," 5 (IQR 4-7) for "average pain," 4 (IQR 1 6) for "current pain," and 3 (IQR 1-5) for "minimal pain," as shown in Fig. 2 [pain intensity in hospitalized patients according to the Visual Analogue Scale (BPI-SF)]. With regards to pain interference with the various activities assessed, sleep and general activity were the most affected, followed by mood and walking, Fig. 3 (Interfer ence of pain in hospitalized patients). Along these same lines, 19.2% of the participants reported considerable pain interference (>8) in at least 1 activity, sleep in particular (12.4%) and general activity (8.5%).

Source: Authors.

Figure 2 Pain intensity in hospitalized patients based on the Visual Analogue Scale (BPO-SF).

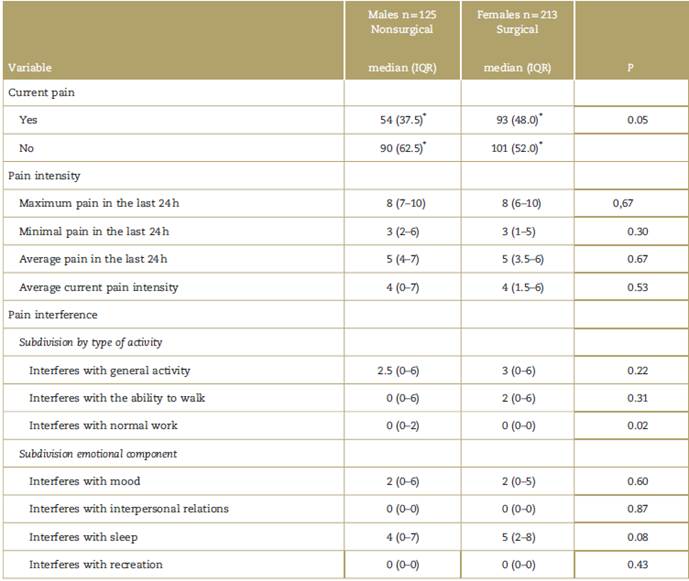

Evaluating intensity and interference by sex, women showed a higher frequency of pain and intensity, particularly with regards to the item "minimal pain in the last 24 hours." However, no differences were identified with regards to pain interference in the various activities by gender Table 2). Similarly, pain intensity and interfer ence in accordance with the type of service was similar in every item, except for usual work Table 3).

Table 2 Pain intensity and interference based on gender

Pain measurements were made with BPI-SF. The differences by gender were estimated using the Wilcoxon test for quantitative variables and x2 for qualitative variables.

IQR = interquartile range.

∗ n (%).

Source: Authors.

Table 3 Pain intensity and interference based on the treating service

Pain measurements were done using BPI-SF. Gender differences were estimated using the Wilcoxon test for quantitative variables and x2 for qualitative variables.

IQR = interquartile range.

∗ n (%).

Source: Authors.

With regards to pain management, 5.4% of the partic ipants who reported pain at the time of the survey were not receiving any pain therapy.

Mutlimodal analgesia was the most frequently used therapeutic approach (64.1%), particularly in the surgical services. When opioids were used, 66.6% were total agonists (Morphine 81.2%, Hydromorphone 18.7%) and this type of opioids were also more frequently used in the surgical, vs the nonsurgical units (85.0% vs 55.0%, P < 0.001).

An analgesia technique (spinal morphine) was used to control pain in less than 2% of the subjects surveyed.

Discussion

In terms of the hospital care quality indicators herein evaluated, the pain prevalence at the time of the survey was 43.4%, with a larger proportion of females and the surgical service. Pain intensity was slightly higher in females, particularly with regards to the item "minimal pain"; however, no differences were found in terms of the type of service. Moreover, interference with the activities did not show any significant differences by gender or treating service; however, patients' reports about interfer ence with their ability to walk and sleep in the surgical services are remarkable.

In accordance with the previous measurements, the same protocol followed in 2013 at the same third-level hospital15 identified a reduction of 24.1% in the prevalence of pain. This decline may be the result of the implemen tation of various awareness strategies for the identifica tion of pain in 2014, including the establishment of the Pain-Free Hospital Policy at the institutional level, including pain as the fifth vital sign, with special specific questions included in the admission record, in the nursing vital signs log form, and the implementation of scales for identifica tion of pain, both for adults and children (4-15 years of age). These strategies may have impacted on the timeli ness of drug therapy, as on the implementation of nonpharmacological measures (physical and verbal re straint, breathing techniques, recreational activities).

A different scenario has been reported at a University Hospital in Canada, where a 13% increased prevalence of pain was found after 2 separate measurements. While the authors fail to mention the reasons behind this difference, it could be the result of a failure to implement the specific strategies to identify and control pain at the institution between 2 evaluation periods of time.2 Moreover, the pain measurement was done using dissimilar instruments (Brief Pain Inventory BPI-SF vs American Pain Society Patient Survey Questions), which could have affected the comparability of results.2,17,18

From the view point of the intensity of both measure ments performed at the same institution,15 moderate to severe pain was experienced in 46.2% of the cases, with a particularly high level in the surgical services; however, there was a decrease in the proportion of patients with this level of pain intensity (51.1% vs 46.2%). In addition, and with regards to intensity for the item "present pain," the previous study reported a similar score (3.7 vs 4); hence, it may be assumed that the effect of all measures to control pain has been constant in the institution.

An additional approach is considered necessary to identify those patient-associated factors and/or factors pertaining to hospital care that condition pain intensity or the evaluation of the effect of treatment strategies (personalized management, multimodal analgesia, anal gesic techniques) in terms of the intensity of this particular symptom.19 This information is comparable to the findings of other trials evaluating the intensity of postoperative pain (54.1%9 and 53.6%20) in Colombian hospitals. Moreover, the frequency of moderate to severe pain was lower vs other international series [Canada: 77%, (2) Italy: 70%, (3) Germany 58%].17 The frequency of moderate to severe pain in these countries is concerning because poor pain management during hospitalization is associated with poor pain control at discharge, leading to higher readmission rates and emergency department visits.21 Furthermore, different studies have identified that the presence of moderate to severe pain intensity during the postoperative period further contrib utes to the development of chronic pain and have recommended the use of regional anesthesia techniques to prevent its occurrence.22

It is common knowledge that pain interferes with the performance of various daily life activities, both at the general23 and hospital level.24,25 People with higher levels of interference in any activities have been found to experience higher levels of anxiety and depression.26 The literature reports that the most commonly affected activities in hospitalized patients are their ability to enjoy themselves (5.7), to walk (5.6), to perform general activities (5.4), and to sleep (5.1), the latter being the most affected among the patients participating in this trial (2). With regards to the above measurement, sleep is the parameter where pain mostly interferes.

In the previous study, the authors coined the term "large pain interference" for those activities with a score equal or greater than 8/10.15 When comparing the findings on this item vs the previous study, a 45% reduction was found (65% vs 19.2%), leading to the assumption that educational interventions are not only reflected in the prevalence of pain but also in pain interference, suggesting that the quality of hospital care has improved. It would be interesting to assess, in patients reporting significant interference, the presence of symptoms such as anxiety or depression in future trials, for a better understanding of the emotional component in pain.

One of the limitations of this trial is related to its cross-sectional nature, which prevents the evaluation of the link between pain intensity and interference, and the impact of prescribed or administered medications. Moreover, the trial failed to consider the indicators based on population types, that is, cancer patients vs pediatric patients, and this requires prior validation trials in order to properly establish the measurement instruments for each specific scenario, particularly for children between three and four years of age. Moreover, it is important to stress that the same methodological approach was used for both the current and the previous trial, with the same measure ment instrument for pain evaluation and the completion of the questionnaire was assisted by the surveyor to clarify any doubts; therefore, the answers were objective and the results comparable between the 2 measurements.

Conclusion

The implementation of strategies aimed at improving pain identification and control in hospitalized patients showed enhanced hospital care quality indicators (prevalence, intensity, and pain interference) measured in this trial.

This type of information allows for superior characteri zation of pain in this population and will provide informa tion to further study the prescription and administration of medications for pain management at the institution.

Ethical disclosures

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data. In addition, national and international ethical guidelines have been followed in the management of confidentiality, ensuring the anonymity of the data.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document work in the power of the correspondence author.

text in

text in