1. Introduction

Population growth and industrialization during the last centuries have caused a dramatic increasing in primary energy consumption. Considering the years 2000-2016, the primary global energy consumption grew from 9,390 to 13,276 million tons of oil equivalent (Mtoe). That is an increase of around 40% in only 16 years. The great concern centers on this energy distribution, where 4.5% comes from nuclear and the rest from fossil resources; oil (33.3%), coal (28.1%) and natural gas (24.1%).

Facing this issue, the scientific global community has focused their efforts on both searching for sustainable energy resources and increasing energy efficiency for current processes. Systems with major potential are those based on solar, wind and biomass among other renewable resources. These have gained ground during the last decades, mainly in power generation, where in 2015, they contributed 23.5% of the total global energy supply. Despite the fact that the renewable market is clearly dominated by hydropower, systems based on wind, solar and biomass are continuously growing as a result of their competitive levelized cost of energy (LCOE), which in some cases have reached similar values to those related to fossil fuel based systems [1].

Biomass is considered as a high potential resource, due to its distribution and availability. Currently, this represents around 10% of the total primary energy worldwide and is referenced as a resource able to supply the total energy demand of society [2,3]. Among the most remarkable advantages are: low cost per energetic unit, easy to store, and abundance in countries with a shortage in power generation (opportunity gap), low environmental dependence and versatility to be turned into heat, electricity, liquid and gas fuels. Additionally, biomass is also produced as a byproduct in some agribusiness processes, where its use for energy purposes would be linked to environmental benefits [4,5].

Among the higher potential processes for biomass energy conversion, gasification with external heat supply is highlighted. This process allows a medium energy density gas production from biomass with moisture contents up to 50%w.t. This producer gas reaches Lower Heating Values (LHV) around 12 MJ/Nm 3 [6] which is able to feed conventional thermal machines or to be used as a precursor for high quality fuels such as hydrogen [7]. Like external energy sources for the process, char, biomass and process byproducts, combustion has been analyzed. Systems with external combustion, usually named as indirect gasification, can be operated up to 1,500 K with efficiencies around 60% and 40% for gasifier and the overall generation process respectively [8-10]. Characteristics of this technology have allowed it to achieve a demonstrative level with powers up to 4 MWth in which the producer gas properties enable it as a precursor of natural gas or other gases with higher quality [7, 11, 12]. It is worth noting that this system keeps the conventional gasifier system characteristics, which have few performance variations over changing environmental conditions.

Additional to combustion processes, concentrated solar power as a renewable energy source for allothermal gasification process has also been analyzed. This technology is considered a promising candidate for gasification because it allows solar energy storage in a chemical medium [13, 14]. In Colombia, there exists several agricultural residues that could be used for solar gasification, among them the most important are: rice, corn, banana, coffee, cane and palm oil industries, which reach municipal primary energy potentials around 20,000 TJ/year [15]. Most of these biomasses are characterized by a high moisture content making it difficult for their conversion into power, due to the high energy demand during the drying sub-process. Considering the aforementioned biomass potential, this work analyzes computationally the allothermal gasification process for lignocellulosic biomass with 50% w.t. moisture content aiming to produce a high hydrogen syngas.

2. Methodology

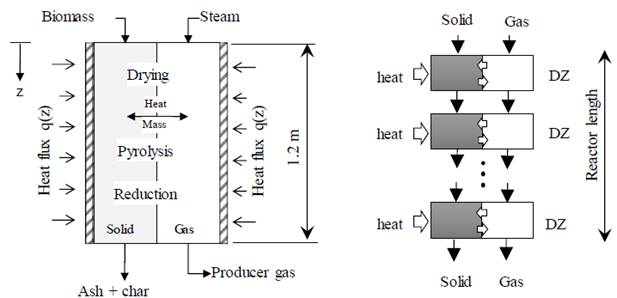

To analyze the process, a one-dimensional kinetic model in transient state was used, which was carried out in [16]. As a summary, the model scheme and discretization are presented in Figure 1. This paper studies biomass gasification for wooden particles with 2 mm of equivalent diameter in a reactor with 0.08 m of internal diameter, 6.3 mm wall thick and 1.6 m of length. Seeking to maximize hydrogen production, steam is supplied as the gasifying agent. The system was heated using a homogeneous flux of 20 kW/m2 achieving the reactor wall, the total energy supplied was 8 kW.

Figure 1 Model scheme using two phases in allothermal gasification. Adapted with permission from [16]

As mentioned before, this system configuration allows for the processing of high moisture content biomass up to 50% w.t. During the drying sub-process, biomass releases a high steam amount which leads to biomass to steam ratio around one. It is clear that a high steam stream in gasification favors the kinetic of those reactions which involve this reactive, thus favoring hydrogen formation. However, its use in excess reduces the thermal efficiency of the process due to the amount of steam which could be higher than required, causing a portion of it to leave the gasifier without having taken part in the reaction, so that, its unique effect would be wasting energy that could be used in the other reactions [17]. Considering the above, a sensibility analyses of steam stream over temperature, main gas components and chemical process efficiency was carried out. To this end, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, 1.25, 1.5 and 1.75 kg/h were chosen for steam flow at 393 K and 1 atm for inlet temperature and pressure respectively. This flow goes into the reactor and mixes with the steam released from the biomass then supplying the gasifying required by the process.

3. Results and discussion

Figure 2a shows how peak temperature is reduced and its location moves toward gasifier gas outlet when the steam flow is increased, this effect is due to the rise of mass flow in the gaseous phase. Steam flow reduction favors the process in terms of high temperature but the availability of this reactive for steam gasification reactions is limited. That is why in Figure 2b an inflection point in the hydrogen concentration profile is observed, being the maximum 45% at steam flow of around 1 kg/h. The flow rate that was used in the experimental study taken for model validation, in which high hydrogen concentration gas was also set as the target [10]. On the other hand, the methane gas exhibits a slightly tend to increase when steam was increased. However, its concentration does not overcome 5%vol of the gas. CO and CO2 show opposite trends, while the CO decreases, the CO2 increases, this is because, under these conditions the water gas shift reaction is favored, increasing the H2 and CO2 production from CO and steam. Furthermore, considering the chemical efficiency ( η chem ), defined as the ratio between the chemical energy leaving the reactor over the total energy input, is worth noting that the maximum hydrogen concentration point does not match the highest efficiency point, in fact, through the analyzed interval, efficiency always diminishes when the steam flow is increased, which is because to the excess of steam used and its consequent reaction cooling effect. As can be noted in Figure 2c, reduces around 5% when the steam was raised from 0.5 to 1.75 kg/h, achieving 33% of efficiency at the optimum hydrogen concentration condition.

From results biomass/steam ratio equal to 1.23 was defined as the optimum operational condition to maximize hydrogen concentration in the syngas. Therefore, this was chosen to analyze the gasifier dynamic behavior. Starting with the gasifier at 300 K and 1 atm for temperature and pressure respectively, the system is heated during 2 hours until reaching the steady state, in both dynamic and steady state, main performance variables are analyzed.

3.1 Dynamic behavior

As shown in Figure 3a, after approximately 3,600 s steady state is achieved, from which, gases outlet temperature does not exhibit remarkable variations achieving steady state around 1,500 K. Additionally to temperature profile, Figure 3a also show biomass, char and water flow variations, which allow computing the beginning and the end of the sub-processes: drying, pyrolysis and gasification. 1,850 seconds after the heating has started, biomass drying was completed, just as process temperature reached 550 K. Then pyrolysis begins and takes around 1,500 s until a temperature of 650 K is achieved allowing the fully release of volatile material from biomass at 2,050 s. The final stages of both drying and pyrolysis were noticed by slop changes in temperature trends as in previous works [18, 19]. During pyrolysis, char formation takes place allowing this specie to remain until bed temperature achieves 1,050 K. Temperature condition that allows the beginning of char gasification reactions. It is worth notate that despite of highest temperatures, char fully depletion is not attained allowing that a rate of 0.3 kg/h of char leave the process. This is typical in conventional gasification systems [20].

Regarding particle equivalent diameter, it remains constant during drying and pyrolysis (model hypothesis), but begins to decrease along with solid phase velocity once char gasification reactions are activated [21, 22] (see Figure 3b). Solid phase velocity always increases achieving its maximum slope during pyrolysis. This parameter attains steady state along with reactor temperatures after 3,600 s of the heating start, after that time only slightly variations are noticed for velocity which indicates its high temperature dependence.

As aforementioned, during the first process stages, biomass drying and pyrolysis take place. The latter allows the release of volatiles, char and tar from biomass, as it can be notated in the increases of these species during the first 1,800 s, whereupon tar and char thermal cracking take place. Char cracking reactions are the major contributors for CO and H2 formations as it can be noticed in Figure 3c, where the increasing trend of these gases matching with the char decreasing trend.

Methane and carbon dioxide present low variations after pyrolysis stage, which reaffirm the highest contribution of heterogeneous reactions on the final syngas composition. This characteristic is also highlighted in the simulation works previously presented by Steinfeld [23, 24], who employs a net endothermal reaction for char and steam. In this work, the use 1.23 for biomass to steam ratio additional to the high moisture content of biomass ensures the steam availability for the whole process. This can be verified with the molar flow of the steam leaving the reactor [Figure 3c), whose separation does not represent a challenge due to the fact that steam is easily condensed through gas cooling.

3.2 Steady state behavior

Finally, Figure 4 presents gaseous and solid specie profiles along with bed temperature for the whole reactor length at steady state (t > 7,200 s). During the first 0.5 m drying and pyrolysis are completed. Char generation begins at approx. 0.1 m, and due to heterogeneous reactions, this is only present until 1.2 m. Although heterogeneous reactions do not occur after char depletion, last 0.4 m of the reactor length are only important for homogeneous reactions which allow the optimization of gas quality. Maximum temperature was 1,070 K at z=1.24 m. Despite the homogeneous gasifier heating along the whole reactor length, process temperature decreases subtly close to the gas outlet due to solid depletion and its corresponding reduction in thermal inertia. During this stage, an increase in H2 and CO concentrations was also notated, this is because the contribution of endothermic reactions: char gasification, water gas shifts and methanation. Free-tar-dry-gas yield was 51.9 mol/h with an average concentration of 51.9 mole/kg of biomass.

4. Conclusions

This work presents the numerical analysis of gasification for a high moisture content biomass using external heat supply, this process was analyzed considering the high potential of agroindustry residues in Colombia which have characteristics similar to the analyzed. According to results, using a biomass with a moisture content of 50 % w.t., the biomass to steam ratio that allow the maximum hydrogen concentration (approx. 45% vol) is 1.23, a value close to the previously reported under similar conditions but in an experimental work. However, it is worth highlighting that the process efficiency decreases when the steam flow increases. Using a power supply of 8 kW, 51.9 mole gas/h are produced. Average concentration of this gas was 45.7% CO, 44.8% H2, 4.8% CH4 and 4.6% CO2. Process temperature to achieve this performance was 1,050 K while efficiency keeps between 30 and 35 %.