Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional gastrointestinal disorder affecting approximately 30% of the world population and is more common in women and developing countries. It is characterized by symptoms of chronic abdominal pain and change in bowel habits1,2. According to the criteria established by the Rome Foundation (Rome IV), it is classified into subtypes: IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS with constipation (IBS-C), IBS with mixed symptoms (diarrhea and constipation) (IBS-M), and IBS in patients who meet the diagnostic criteria, but do not fit into any of the above categories (IBS-U)2.

It is a functional condition characterized by gut-brain axis (GBA) dysfunction. The altered functioning and balance of the GBA and the microbiota may trigger adverse reactions that cause the typical gastrointestinal symptoms of IBS3. One reason that can lead to this alteration is the chronic stress the patient is subjected to in their environment. Commonly, patients who have signs of depression and anxiety present with symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea, and decreased appetite, altering eating patterns4. Epidemiological data have shown that 40% to 90% of patients suffering from IBS also meet the criteria for diagnosing a mental disorder, especially depression and anxiety1.

Even when the importance of the psychological factor in IBS has been recognized, information is scarce about how these altered mental states affect the relationship with food of the patient with IBS and to understand and devise strategies for optimal treatment.

Therefore, this article aimed to explore the relationship between stress, mental disorders, and eating habits in individuals with IBS. Hopefully, this article may help understand the existing relationships and make proposals to define strategies for clinical management with a comprehensive approach to the syndrome, especially in the nutritional field.

Materials and methods

Research on the relationship between mental disorders, stress, and eating in IBS is recent and imprecise. Thus, we decided to conduct a scoping review to determine the existing literature on the subject matter, particularly when it has not been extensively reviewed or is of a complex or heterogeneous nature5.

We followed the five-step methodology suggested by Arksey and O’Malley6 and the PRISMA extension for scoping review published in 2018, consisting of 20 essential items and two optional items to be included in this type of work7.

The information search was carried out through PubMed, ScienceDirect, the Virtual Health Library (VHL) Regional Portal, and Google Scholar databases. The DeCS terms “síndrome de intestino irritable,” “depresión,” “ansiedad,” “estrés psicológico,” and “hábitos alimentarios” were used. Regarding the MeSH terms, only the term “irritable bowel syndrome” was employed due to the specificity of the search.

For this review, we built the following search equations: ((gut-brain axis) AND (microbiota) AND (irritable bowel syndrome [MeSH])), ((irritable bowel syndrome [MeSH]) AND (microbiota) AND (serotonin)), ((stress) AND (gastrointestinal symptoms)), ((anxiety) AND (gastrointestinal symptoms)), ((depression) AND (gastrointestinal symptoms)), and ((irritable bowel syndrome [MeSH]) AND (feeding behavior)).

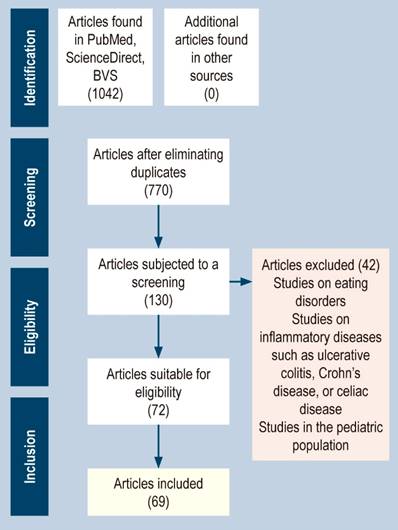

The types of studies (clinical trials, systematic reviews, literature reviews, and meta-analyses), studies conducted in humans, and language (Spanish or English) were considered inclusion criteria. The time window was not considered as an inclusion criterion since, being a recent and heterogeneous research topic, there are few related publications. The articles’ titles, keywords, and abstracts were considered selection criteria. We excluded publications or studies in the pediatric population or dealing with eating disorders or other inflammatory diseases of the digestive system, such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, or celiac disease (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Flowchart of the study identification and selection process according to the PRISMA method for scoping review articles. Source: The authors.

After selecting the articles, an information extraction matrix was created in Excel, and the Mendeley reference manager was used. We employed the title, year, country, author(s), objective, materials and methods, and critical results fields for data extraction.

Finally, to summarize the findings, they were classified into the following lines of research: “mental disorders, stress, and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with IBS,” including the relationship between mental disorders (anxiety, depression, stress) and possible gastrointestinal symptoms involved in IBS; “eating habits in people who suffer from IBS,” describing how the IBS symptoms may modify the eating habits of individuals who suffer from it, and “gut-microbiota-brain axis and IBS,” involving the relationships between the central nervous system, intestinal microbiota, IBS, neurotransmitters, and metabolites. The preceding describes the possible mechanisms that explain the associations between IBS, mental disorders, and eating habits.

Results

Of the 130 articles selected for screening, 70 published between 2007 and 2021 were included, most of which correspond to 2021. Most of the articles published were from European and East Asian countries4,8-14, which is contradictory considering that these countries have the lowest prevalence of IBS2. On the one hand, most of the texts used were literature reviews that sought to establish the relationship between the gut-microbiota-brain axis and the development of IBS. On the other hand, clinical studies (randomized clinical trials and prospective studies) aimed to prove the variation in the microbial population of people with IBS and their concentration levels of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) and serotonin. We also investigated clinical practice guidelines (CPG) for managing IBS and found four.

Mental disorders, stress, and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with IBS

Hans Selye first defined stress in 193615 as the physiological response to psychological or genuine threats. When an acute stressor appears, a “fight or flight” response is triggered, preparing the body to defend itself and ensure its survival. However, when the stressor is chronic, it becomes harmful since it does not allow the achievement of basal homeostasis.

It has been noted that patients with IBS tend to have an increased response to stress, which has involved a possible mechanism contributing to the syndrome’s pathology14,16. The reason is that stress could induce changes in intestinal motility, permeability, and secretion, as well as visceral sensitivity that causes the reactivation of previous enteric inflammations and subsequent inflammatory stimuli16,17; furthermore, it may alter the composition and function of microbiota18.

Similarly, traumas during a person’s life produce chronic stress that can lead to developing IBS15. Particularly, traumas experienced at an early age (sexual, physical, or psychological abuse, serious illness, or death of a parent, among others) have been associated with higher risks of suffering gastrointestinal discomfort and higher chances of suffering from inflammatory diseases in the digestive system such as IBS. These events may result in long-term epigenetic changes in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, with altered negative feedback of glucocorticoids and increased susceptibility to stress-related disorders in adulthood19.

In addition to a frequent number of people with IBS and stress, those suffering from IBS show a high prevalence of suffering from mental disorders such as anxiety and depression due to continuous exposure to stressful stimuli. Between 20% and 90% of patients with IBS suffer from severe psychiatric symptoms that may be diagnosed as a disorder17,20. A prospective study conducted by Koloski et al.21, with a 12-year follow-up of more than 1,000 individuals, found that those with high anxiety and depression were more likely to develop IBS.

Anxiety related to gastrointestinal symptoms is known as specific gastrointestinal anxiety (AGE) and influences the severity of symptoms and the quality of life of individuals with gastrointestinal diseases22. Van Oudenhove et al.23 found an association between psychosocial morbidity (anxiety, depression, and somatization) and increased gastrointestinal symptoms. Specifically, they detailed that increased levels of anxiety and depression were related to the appearance of symptoms such as bloating, abdominal pain, and nausea in the postprandial period24. Studies have shown that higher levels of anxiety and depression lead to a more significant reduction in pain thresholds caused by a readjustment in the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and neuroendocrine pathways that increase pain perception25.

Eating habits in people with irritable bowel syndrome

Stress and mental disorders in irritable bowel syndrome and its relationship with food intake

Stress and mental disorders increase or decrease eating, as exposure to stress produces both orexigenic and anorexigenic substances in the body26. Chronic stress increases the activation of the orexigenic pathways, which intensifies the intake of foods rich in calories and carbohydrates that are “appetizing” for the person and interrupts specific sensory satiety signaling, which results in the consumption of a particular food over and over again. In contrast, when there is an absence of foods rich in calories or that are appetizing, stress activates the anorexigenic pathways, so food intake decreases; activation of this pathway can be acute or sustained over 24 hours27.

It has been shown that, under acute stress conditions, norepinephrine suppresses appetite and, together with other catecholamines, increases blood pressure and heart rate, and decreases blood flow in the digestive and renal systems and the skin28. Altered regulation of the HPA axis due to chronic stress modifies the production of cell fusion protein 1 (CFR1), which acts as an anorexigenic substance that influences food intake and energy balance. CFR1 is believed to decrease the synthesis of neuropeptide Y (NPY) and its release and increase the production of leptin, known as the satiety hormone19,28.

Gastrointestinal symptoms and negative perceptions of food

Gastrointestinal symptoms have a high relevance in the perception of pleasure when eating, the selection of food, and participation in daily life activities. Usually, patients with a disease or syndrome related to the gastrointestinal system tend to develop negative perceptions of food and avoidance behavior in social situations due to the discomfort caused by the gastrointestinal symptoms of the pathology29.

Fear and anxiety around gastrointestinal symptoms when eating increases restrictive or disordered eating practices, decreasing appetite due to gastrointestinal symptoms derived from eating30. Food restriction is a risk factor for disordered eating associated with reduced quality of life, maladaptive coping mechanisms, depression, and perceived stress.

Cuomo et al.31 found that more than 60% of IBS patients reported the onset or worsening of gastrointestinal symptoms 15 minutes after meals, in addition to high food intolerance associated with reduced quality of life. According to the authors, this intolerance often makes patients identify and eliminate foods they do not tolerate. It was found that 62% of individuals with IBS limited or excluded foods from their diet32. A study with 1,717 Korean students revealed that individuals suffering from IBS tended to skip their daily meals frequently, unlike healthy subjects. These results were similar to those in other studies conducted with middle-aged people and a study conducted with nursing and medical students in Japan33.

Petrillo et al.34 found that 57% of the individuals who had decreased food intake met the criteria for psychiatric disorders and were also associated with abdominal distension, pain, irregular bowel habits, fatigue, and headache. Several studies that have evaluated daily eating patterns find a significant decrease in the intake of calories, protein, and carbohydrates, including fiber, and low values compared to the daily recommendation of micronutrients such as calcium, thiamine, and folates in individuals with IBS, in contrast to healthy controls30,34,35. Individuals with gastrointestinal diseases often have irregular schedules, skipped meals, and a more restricted intake.

In a study conducted by Melchior et al.35 in 2021, 26% of patients with IBS reported that they frequently did not eat when hungry due to the same disorder, 54% stated that they often avoided food, and 31% said that they had an aversion to food. In a case-control study by Hayes et al.36, patients with IBS had a risk factor of 3.96 for developing irregular eating habits compared to healthy controls.

Dietary recommendations for irritable bowel syndrome

Diet is critical, considering that 60% of patients with irritable bowel claim that certain foods worsen their symptoms. Generally, dietary indications to treat IBS symptoms include reducing the intake of lactose, fats, gas-producing foods (such as legumes, pulses, and broccoli, among others), a diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP), which is the most common, and adequate fiber supply, especially soluble37. According to the 2016 Colombian CPG38, with a strong recommendation but insufficient evidence, professionals state that the implementation and adherence to a low FODMAP diet are advised to treat patients with IBS who present with bloating, abdominal pain, and diarrhea because these carbohydrates increase intraluminal osmotic pressure and provide a substrate for bacterial fermentation, resulting in gas production, bloating, and abdominal pain39.

However, in some articles, despite reducing some of these compounds in the diet, some people with IBS still show a degree of food aversion and restriction and report high severity in gastrointestinal symptoms35. The preceding can be related to the stress at eating time due to perceived gastrointestinal symptoms or other external stress situations and the same mental disorders that cause dysregulation in eating habits and appetite.

Diets based on eliminating foods to which patients with IBS are “intolerant” may increase the risk of developing avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). The DSM-5 defines it as a disorder that occurs when a disturbance in food intake causes the inability to meet appropriate nutrient or energy needs, leading to weight loss or nutritional deficiency and, in more severe cases, dependence on enteral feedings or dietary supplements. Usually, this disorder is not motivated by fear of gaining weight or dissatisfaction with body image but by low interest in eating or hyporexia, aversion to the sensory characteristics of some foods, or worry or fear of the consequences of eating certain foods29,40.

Most patients who develop ARFID have been prescribed a low FODMAP diet due to maladaptive eating behavior that pushes them to avoid the phase of food reintroduction, reducing their diet to only 10 “safe foods”29,41. Notably, more than 70% of these patients already met the criteria for ARFID, low weight, or some mental disorder when prescribing the diet29. According to the data obtained by Mari et al.42, greater adherence to a low FODMAP diet is associated with symptoms related to eating disorder behaviors. All patients who tested positive for an eating disorder had a percentage of adherence of 57.4% compared to 35.8% in those who tested negative for eating disorders.

In general, Kayar et al.43 discovered that out of 200 patients, 118 (59%) were women, and 92 (41%) were men. The eating attitudes test (EAT) score was significantly higher in the IBS group (odds ratio: 5.3; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 4.3-9.3; p < 0.001). The number of subjects with an EAT score > 30 was significantly higher in the IBS group (p < 0.001). In addition, higher scores were found in female patients with IBS and younger ages, considering a broad age range between 18 and 65 years (p = 0.013 and p = 0.043, respectively). At the same time, there was no significant association between the IBS subtype and the EAT score (p > 0.05). However, the intensity and duration of IBS had a positive correlation with the EAT scores, which justifies some comments by other authors that the presence of IBS is linked to disordered eating and even with eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia, and unspecified disorders44.

Food restriction has also been related to the possibility of sub-adequacy in nutrient needs; for example, low dairy intake leads to insufficient calcium, vitamin B12, riboflavin, and vitamin D, or low fat intake may imply inadequate intake of fat-soluble vitamins. Patients suffering from IBS have been found to have low concentrations or deficiencies of vitamins A and riboflavin and minerals such as calcium and potassium37.

Irritable bowel syndrome and abdominal obesity

Recent research, such as that of Akhondi et al.45, has determined that IBS is more frequent among individuals with abdominal obesity compared to subjects with average weight (23.8% vs. 19%). This condition could be related to eating habits. Nonetheless, the association between IBS, obesity, and overweight was no longer significant after adjusting for possible confounding factors (odds ratio [OR]: 1.09; 95% CI: 0.82-1.44). In the categories of body mass index (BMI), they found no significant association between overweight (OR: 0.89; 95% CI: 0.62-1.27), obesity (OR: 1.05; 95% CI: 0.58-1.87), and the severity of abdominal pain. Abdominal overweight (OR: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.65-1.40) and obesity (OR: 1.61; 95% CI: 0.67-1.63) were not associated with the intensity of abdominal pain. Therefore, further research is required looking forward.

Gut-microbiota-brain axis and IBS, possible mechanism to explain the relationship of IBS symptoms with mental disorders and eating habits

At the core of the gut-brain (GBA) axis is the connection between the enteric nervous system (ENS) and the central nervous system (CNS), which creates direct “bottom-up” and “top-down” communication. Downstream, the ECI enables central regulation of gut function and facilitates gut responses to emotion and cognition; upstream, the responses to stimuli derived from the intestine influence the cognitive and emotional centers of the brain46. This modulation occurs through sympathetic and parasympathetic inputs from ANS neurons. It could be part of the mechanisms that explain the relationships between IBS gastrointestinal symptoms, mental disorders, and changes in eating habits.

Gut microbiota

The gut microbiota is the latest component of this network to be recognized. Commensal organisms in the gut have been shown to have the ability to directly influence the ENS and indirectly modulate ECI function20 via numerous pathways, including the immune system, the recruitment of neuroendocrine signals, direct ENS pathways, and the vagus nerve, and the production of bacterial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), bile acids, serotonin, branched-chain amino acids, and peptidoglycans9,47,48.

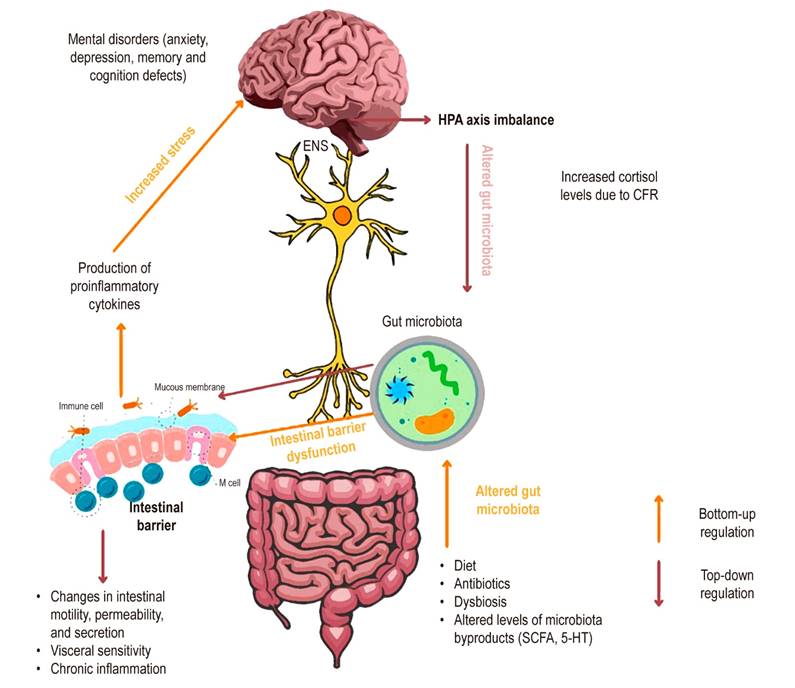

Mayer and colleagues18 have proposed that signaling between the brain, gut, and microbiota may contribute to dyspepsia and that the microbiota may mediate the modulation of enteric reflexes that cause IBS-related symptoms. A local change in microbes in the gut microbiota leads to inflammation that may allow bacterial translocation along with an increase in proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and mediators such as serotonin, which induce increased sensitivity to pain and changes in motility, possibly through effects on the interstitial cells of Cajal17,49,50. This situation may be reinforced by mental disorders such as depression and anxiety that alter the flow of the ANS with increased levels of catecholamines, which in turn increase the production of an adrenocorticotropic-releasing hormone (CRF) and the secretion of cortisol (Figure 2)17.

Figure 2 Alteration of the gut-microbiota-brain axis in IBS. The gut-microbiota-brain axis is connected through the enteric nervous system, creating two-way communication. Upstream, microbiota alteration by factors such as diet, antibiotics, or dysbiosis changes the concentration levels of the derivative metabolites (SCFA*, 5-HT**), which leads to intestinal barrier dysfunction. As a result, chronic inflammation and the production of proinflammatory cytokines can increase stress and cause an imbalance in the brain and the possible development of mental disorders such as depression and anxiety. Downstream, an imbalance in the HPA axis increases cortisol levels induced by CFR, causing the rise of the catecholamines that impact intestinal bacteria, intestinal inflammation, and changes in intestinal motility. *Short-chain fatty acids. **Serotonin. CFR: corticotropin-releasing factor; HPA: hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Source: The authors.

Moreover, it has been found that the intestinal microbiota composition in patients with IBS usually differs from that of healthy individuals. Several studies have identified that those individuals who suffer from the syndrome have a greater bacterial richness of Ruminococcus sp, Clostridium spp, and proteobacteria, which are linked to IBS symptoms, including visceral hypersensitivity and changes in SCFA values that are associated with altered levels of fecal cytokines. There are also deficiencies of Bifidobacterium sp, Roseburia, Faecalibacterium, and Lactobacillus, which help promote intestinal health3,11,49,51. Bifidobacterium supplies a mucosal barrier that helps maintain intestinal homeostasis, and Lactobacillus is essential for increasing mucin production in the intestinal lining, preventing pathogenic microbes’ adherence. Meanwhile, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is a significant butyrate producer that promotes intestinal inflammation reduction and releases other important metabolites to improve the mucosal barrier function4.

The gut microbiota plays a vital role in neurodevelopment during the pre- and postnatal period and affective behavior in adulthood. Dysbiosis of the pregnant mother may alter the signs of normal development or induce inappropriate developmental stimuli52. Inflammation caused due to disruption of the gut microbiota results in a proinflammatory state that can affect neural development and the fetal immune system. Among the causes of maternal dysbiosis are the use of antibiotics, high fat intake, and physical or psychological stress that can suppress the production of immunoregulatory metabolites such as SCFAs or promote the production of proinflammatory metabolites53. The maternal gut microbiota can also affect circulating levels of serotonin (5-HT), which in turn alters fetal neurodevelopment because this metabolite regulates the division, differentiation, and synaptogenesis of neuro-fetal cells54.

Disruption of the microbiome in the first years of life influences long-term adverse mental health outcomes through its interaction with the gut-brain axis55. In neonates born vaginally, the gastrointestinal tract is colonized mainly by bifidobacteria, lactobacilli, Bacteroidetes, proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria. In contrast, those born by C-section have a higher amount of Escherichia coli and Clostridia and a lower amount of Bacteroidetes and bifidobacteria. Breastfed infants show a greater abundance of bifidobacteria, while in formula-fed infants, bifidobacteria, Bacteroides, clostridia, and staphylococci were found in equal amounts56.

The species Clostridium spp., which, as mentioned, is usually found in more significant amounts in children born by C-section and fed with formula milk and in patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder and IBS, is responsible for producing acetic acid, which also seems to be increased in IBS51. Acetic acid plays a relevant role in suppressing appetite by activating acetyl-CoA carboxylase and its effect on the expression of regulatory neuropeptides in the hypothalamus57, which could indicate that the levels of these hormones are altered when SCFA concentrations are limited due to a change in the gut microbiota composition. People with IBS have abnormal peptide YY (PYY) levels and abnormal cholecystokinin (CCK) responses to food intake, increasing rectal mechanosensitivity. Similarly, it has been identified that mood disorders, such as depression, are associated with genetic polymorphisms that can alter CCK and PYY levels24,56.

Short-chain fatty acids

Microbiota-derived SCFAs maintain intestinal homeostasis and have a dual role in immunity: anti-inflammatory, by strengthening the integrity of the epithelial barrier through upregulation of G protein-coupled receptors in the intestine, and induction and maintenance of regulatory T cells that enhance the integrity of the epithelial barrier. In contrast, in cases of dysbiosis, SCFAs induce mucosal inflammation via tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1) transcription and 5-HT production via the serotonergic pathway, accounting for low-grade inflammation in the pathogenesis of IBS58.

Besides, 95% of these SCFAs are made up of acetate, propionate, and butyrate, produced from carbohydrates in the colon. Acetate and propionate regulate fatty acids and energy in the liver51. Butyrate is involved in the modulation of intestinal epithelial proliferation, apoptosis, and cell differentiation in the intestine and the inhibition of the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B-cells (NF-κB) while maintaining the integrity of the intestinal barrier49.

A study by Tana et al.59 detected significantly higher levels of acetic acid and propionic acid in patients with IBS than in controls. However, other studies show that fecal SCFA of patients with IBS was characterized by lower levels of total SCFA, acetic acid, and propionic acid and higher levels of butyric acid8,60. Although there is still no consensus on the differences observed in SCFA levels, alterations in SCFA composition and concentration are evident in patients with IBS, especially in patients with IBS-D, in whom differences in SCFA production by the colonic microbiota are associated with an accelerated rate of bowel transit and neuromuscular dysfunction8,10.

Serotonin

About 90% of the 5-HT in the human body is found in the gastrointestinal tract, mainly in enterochromaffin (EC) cells and myenteric interneurons13. Inflammation and the development of neurons are essential for peristalsis and intestinal secretion. 5-HT is related to pain, sensitivity, and reflexes through the activation of EC and enteroendocrine cells16,51. It has been shown that abnormalities in the metabolism of this neurotransmitter may be associated with functional bowel diseases and anxiety disorders. Clinical studies have observed that patients with IBS-C have low postprandial serum 5-HT levels related to slow bowel transit. At the same time, high concentrations are more common in patients with IBS-D, which is related to a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with IBS-C, probably due to intestinal serotonin imbalance and reduced serotonin response in central and peripheral regions16,61.

Recent studies have discovered that the 5-HTTLPR polymorphic variation of the gene encoding the serotonin transporter protein (SERT) increases the expression of the transporter and enhances its activity, increasing serotonin uptake and, in turn, decreasing its effects on secretion and motility. Hence, this polymorphism may be found in patients with IBS-C62-65.

Changes in serotonin concentrations are not only reflected at the level of intestinal metabolism. They can also alter intestinal signaling and visceral nociceptive processes, causing greater sensitivity to abdominal pain66,67.

The corticotropin-releasing factor signaling system

The CFR signaling system is a critical pathway in the biochemical mechanism by which the brain translates a stimulus into an integrated physical response. This system directly affects the gastrointestinal tract, producing proinflammatory effects primarily mediated by CFR1. The latter is expressed in enteric neurons and the intestinal mucosa layer, which delays gastric emptying and accelerates colonic transit15,68,69. CFR also plays a primary role in stimulating the HPA axis in response to physical or psychosocial stress: it increases catecholamine levels, which impact gut bacteria, and cortisol levels, which stimulate bile acid production in the liver and affect the microbiota15,69. Evidence suggests that patients with IBS have deregulation in the HPA axis in baseline conditions with an improved systemic response, which increases basal cortisol levels and anxiety symptoms16.

Discussion

Although in recent years, the information on the relationship between the psychological and metabolic factors that come together in IBS has increased, there is still a little-studied condition in these patients about these factors influencing IBS symptoms and changes in eating habits.

Among the mechanisms apparently associated with developing IBS are abnormalities in brain structure and the functioning of the gut-brain axis that cause a greater emotional response, higher visceral sensitivity, altered affective behavior, and changes in gastrointestinal function and gut microbiota composition. Structural and connective changes within sensory regions of the brain may result in increased abdominal pain sensation. They explain the increased affective comorbidity observed in IBS patients, especially as deficient modulation of the “upstream” gut-brain pathway and hyperactivity of the amygdala and anterior insula have been noted in anxiety disorders20,68.

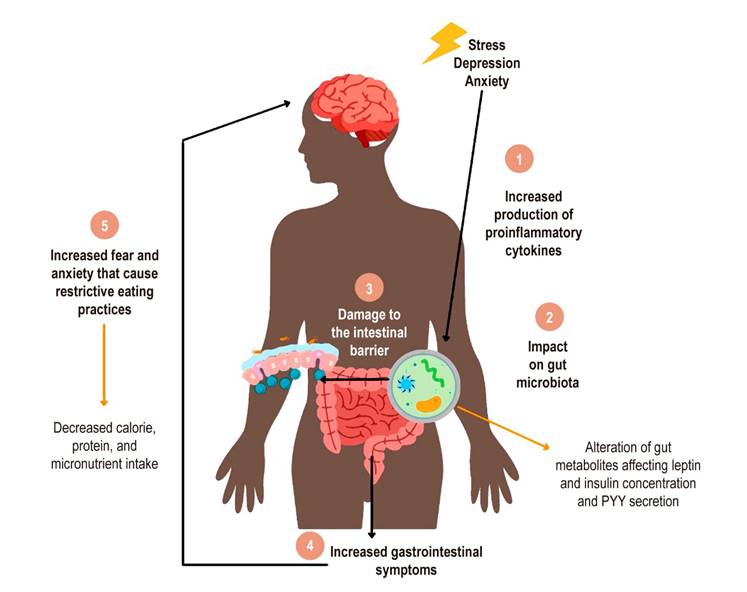

According to the evidence, the relationship between gastrointestinal symptoms, mental disorders, and eating seems to occur in different pathways, many associated with the gut-microbiota-brain axis11. Gastrointestinal symptoms of IBS can be related to negative perceptions of food and changes in appetite. Mental disorders may change a person’s eating habits, gastrointestinal function, and nutritional status, among other relationships70. Likewise, diet changes to manage IBS induce effects on food intake, mental state, and sub-adequacy of some nutrients (Figure 3).

Figura 3 Modelo del rol de los trastornos mentales en la afectación del hábito alimentario de las personas con SII. 1. El estrés psicológico, la ansiedad o la depresión aumentan la liberación de citocinas proinflamatorias. 2. Estas citocinas impactan en la conformación de la microbiota intestinal, lo que puede alterar los niveles de metabolitos y, a su vez, los niveles de las hormonas que regulan el apetito. 3. La pérdida del equilibrio bacteriano de la microbiota y el aumento de citocinas proinflamatorias causan daño en la barrera intestinal. 4. Hay un aumento de los síntomas gastrointestinales como el dolor visceral, motilidad intestinal, distensión abdominal y generación de gases. 5. El aumento de los síntomas gastrointestinales incrementa el miedo y la ansiedad al ingerir un alimento, lo que causa prácticas de alimentación restrictivas en el paciente con SII. Fuente: elaboración propia.

All the above supports the recommendations that for individuals with IBS, it is essential to establish comprehensive therapy that includes psychological and, if necessary, psychiatric treatment. It should always be accompanied by nutritional guidance that provides dietary alternatives based on recommendations that modify some dietary practices or the intervention of the low FODMAP diet, including a phase of personalization, and allow adequate nutrition and the prevention of future diseases.

It is relevant to include recommendations that promote lifestyle changes, such as physical activity or active breaks during working days, that help manage the stress of daily life and improve gastrointestinal function71. Psychological therapy in treating IBS not only helps to improve mood states but also has effects on pain perception, visceral hypersensitivity, and gastrointestinal motility, as well as possible favorable effects on appetite and food intake. Among the psychological therapies, relaxation, multi-component, and cognitive behavioral therapy stand out, which have been highlighted as more effective in patients with IBS2.

As regards dietary recommendations, the subtype of IBS, the presence of a mental disorder, whether or not the patient already has low weight, and the risk of suffering from an eating disorder should be assessed before prescribing any restrictive diet42. The British Dietetic Association’s 2016 guidelines72 consider a low FODMAP diet, eliminating foods high in these carbohydrates for only four weeks. They also recommend the use of probiotics for four weeks. With less evidence, they advise controlling alcohol use and spicy and high-fat preparations. Meanwhile, with moderate evidence, the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology73 recommends soluble fiber.

Gut dysbiosis and low-grade inflammation reflect the complexity of the relationship between the gut microbiota, the development of IBS, and mental disorders. The importance of regulating the microbiota from the prenatal period is suggested to ensure that the mother maintains healthy eating habits and that her pregnancy occurs in a calm environment, supported by the family and health personnel, and to prevent infections during pregnancy. The significance of breastfeeding infants is highlighted since it not only helps to develop and protect the baby’s immune system but also promotes the formation of a healthy microbiota and could be or act as a protective factor against diseases such as diabetes, obesity, IBS, and the onset of mental disorders in adult life55.

The world is currently experiencing a public health emergency due to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which is responsible for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The rapid increase in outbreaks worldwide led to the declaration of a global pandemic on March 11, 2020, and most governments instituted quarantines and lockdowns to reduce the number of new infections. Although there are still no conclusive data on the prevalence of IBS globally and regionally during the pandemic, it is clear that COVID-19 as an infectious disease has increased the number of cases of people with IBS and IBS-post-infectious (IBS-PI). It has had a significant impact on mental health globally, not only because of the psychological distress experienced in the acute phase of the illness but also because of the isolating environment and the uncertain sequelae of lockdown that create anxiety and panic74. The pandemic has probably affected the eating habits of citizens, who have resorted to increasing foods rich in carbohydrates and fats to feel comfort75. A study by Remes-Troche et al.76 with 678 patients, in which the incidence of constipation symptoms was evaluated during the lockdown implemented to contain the spread of COVID-19 in Mexico, found that this change in eating habits increased the numbers of “new onset” constipation, a significant decrease in the number of stools, and harder stools.

Thus, the comprehensive management of IBS that encompasses the dietary and pharmacological treatment of symptoms and includes psychotherapeutic support is vital to guarantee a better quality of life for individuals suffering from IBS. Implementing a low FODMAP diet, as suggested by the CPG, or identifying intolerable food groups are excellent options to treat this syndrome; however, they are not usually effective in all patients. Complementary alternatives such as promoting physical activity or yoga should be considered, which, in addition to helping to improve gastrointestinal symptoms, can be a tool for managing mental disorders. Within the diet, increasing the intake of soluble fiber and water could help improve bowel transit, particularly in patients with IBS-C.

The possibility of using probiotics that protect and strengthen the intestinal microbiota could also be evaluated. Among these, Bifidobacterium infantis and Lactobacillus salivarus have been demonstrated to significantly reduce abdominal pain, bloating, and difficulty in bowel movement. It has also been found that the Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain could improve gastrointestinal symptoms of IBS and reduce symptoms associated with depression and anxiety77. In addition to probiotics, specific interventions aimed at modulating the gut microbiota in IBS are mentioned, including prebiotics, symbiotics, particular diets, fecal transplantation, and other possible future approaches useful for IBS diagnosis, prevention, and treatment78.

It would be appropriate to conduct a more in-depth evaluation of the functioning of the CNS and ENS in patients suffering from IBS and some mental disorders. These aspects may lead to developing drugs and non-pharmacological therapies more specific to the etiology of IBS in each patient to guarantee a better quality of life.

Conclusion

A relationship was found in various pathways between stress, depression and anxiety, IBS symptoms, and changes in eating habits. Some of these relationships are explained to a considerable extent by the regulation in the gut-brain axis, which is probably not the only mechanism. Therefore, the gastrointestinal symptoms of IBS and changes in mood and eating may be associated similarly with variations in the regulatory function of the gut-microbiota-brain axis. Comprehensive management should involve not only pharmacological treatment for IBS symptoms or states of anxiety and depression but also psychological therapy79 with a personalized nutritional management plan and healthy lifestyle recommendations involving physical activity and stress management79,80.

text in

text in