Introduction

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy is widely used for enteral nutrition in patients who have difficulty feeding orally. Minor complications, which occur in 16.4% to 66.3% of cases, include peristomal infection. Major complications, occurring in 6.1% to 17.5% of cases, include fistula formation and buried bumper syndrome (BBS), which can manifest from weeks to years after the procedure. It is estimated that one in four children will be hospitalized due to complications following PEG placement (1-3.

Clinical case

A 4-year-old female patient with a history of cerebral palsy and PEG placement one month prior presented with a 24-hour history of feeding difficulties. A thoracoabdominal X-ray confirmed that the tube was in the correct anatomical position (Figure 1).

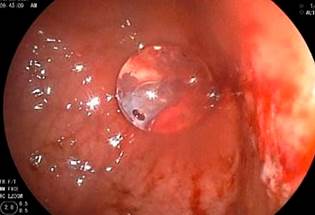

A diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy was performed under general anesthesia, revealing hemorrhagic mucosal erosions at the junction of the body and gastric antrum over the umbilicated area, with no evidence of the internal bumper of the gastrostomy tube (G-tube), consistent with grade III BBS (Figure 2).

Author’s file.

Figure 2 Diagnostic endoscopy showing hemorrhagic mucosal erosions at the junction of the body and gastric antrum over the umbilicated area, with no evidence of the internal bumper of the G-tube, consistent with grade III BBS.

Since our institution does not have a modified sphincterotome for BBS (Flamingo Set; Medwork, Hochstadt, Germany) (4 and due to the risks associated with surgical procedures, the following steps were taken under endoscopic guidance:

The tube was cut externally, 3 cm from the abdominal wall.

A 3 mm laparoscopic grasper forceps (Figure 3) was introduced through the tube end to dilate the internal opening.

A 5 mm laparoscopic hook forceps (Figure 4) was introduced through the channel.

The gastric mucosa over the internal bumper area of the gastrostomy was resected radially at the 12, 3, 6, and 9 o’clock positions, with monopolar cauterization (Figure 5).

The tube was pushed, revealing the internal bumper of the G-tube (Figure 6).

A biliary guidewire was introduced through the tube.

The segment of the G-tube was pushed into the gastric chamber.

Using the guidewire, an 18 Fr Mic-Key gastrostomy button was placed.

The balloon was inflated, confirming proper placement (Figure 7).

The internal bumper was removed using a cold polypectomy snare along with the endoscopy equipment, completing the procedure without complications. Feeding was initiated 24 hours later with good tolerance and progress.

Author’s file.

Figure 5 Radial resection of the gastric mucosa over the internal bumper area of the gastrostomy at the 12, 3, 6, and 9 o’clock positions.

Discussion

BBS is a rare complication following PEG, with an incidence of 1.5%. Although it typically occurs later, not before four months post-procedure, cases have been reported as early as 21 days after PEG placement, similar to the timeframe in our patient1,2,5.

The internal bumper of the PEG can lodge at any level between the gastric wall and the skin along the initial tract of the G-tube, often due to the external button being too tightly secured to the abdominal wall. This tightness gradually causes the internal bumper to erode the gastric mucosa, leading to the partial or complete migration of the bumper into the gastric wall. This migration results in ischemia, necrosis, and the subsequent formation of granulation tissue, causing the bumper to become embedded in the abdominal wall and completely obstruct the internal lumen of the button. Another mechanism involved is the external traction of the tube, which injures the gastric mucosa 6,7. Additionally, changes in the physical characteristics of the internal bumper due to gastric secretions can facilitate damage to the gastric tissue and subsequent migration of the bumper3,5.

The main symptoms are the inability to advance the tube into the gastric lumen, loss of patency, and peristomal leakage7. However, this triad is not always present, as the blockage can be intermittent, or there may only be leakage of gastric contents or symptoms of peristomal infection such as edema, erythema, and pain. Difficulty infusing food, requiring increased pressure, or the inability to pass food will present in more advanced stages when the obstruction is complete. In extreme cases, the internal bumper may be palpable under the skin. There may also be a history of significant traction on the gastrostomy button7,8. Risk factors include prolonged immobility, traction on the device, lack of preventive maneuvers, and non-cooperative patients or children, which is consistent with the cerebral palsy patient in this case. Regarding the device, important factors include the material, insertion method, the distance between the external button and the skin, and the traction applied during use.

For diagnosis, imaging studies are crucial as they determine the extent of internal bumper migration and the patency of the tract. A computed tomography (CT) scan can reveal a migrated gastrostomy button; with fluoroscopy, if the gastrostomy tract remains open, contrast may reach the gastric cavity, potentially leading to a missed diagnosis. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) facilitates locating the internal bumper to determine whether surgical or endoscopic treatment is necessary4,5. Panendoscopy is the definitive study to confirm the diagnosis, revealing mucosal ulceration in early stages or granulation tissue covering the internal bumper, with or without a visible residual fistula. It also allows for PEG replacement.

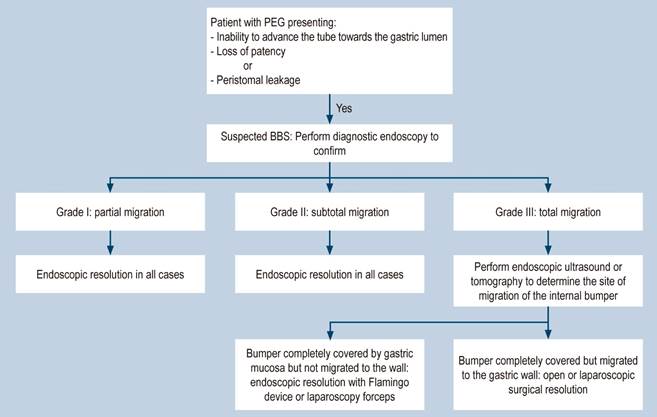

Three degrees of severity have been proposed9:

Grade I: Partial migration Symptoms range from asymptomatic to mild, such as abdominal pain or ostomy infection.

Grade II: Subtotal migration. Accompanied by tube dysfunction and feeding leakage.

Grade III: Total migration. Manifests as tube obstruction. Due to the low incidence, treatment is not standardized and depends on the type of device and the depth of internal bumper migration.

In the literature, endoscopy is recommended if the internal bumper is covered by gastric epithelium and has minimally eroded the musculature. A guide or dilator is introduced to push the internal bumper towards the stomach, allowing for standard replacement2. If the bumper is completely covered by gastric mucosa, it must be freed with a papillotome and radial cuts to facilitate mobilization and then proceed with the standard replacement. However, if the migration is towards the abdominal wall, a surgical approach is required, either via exploratory laparotomy or laparoscopic surgery2,6,9. Costa and colleagues, in a multicenter study, evaluated the safety and effectiveness of a device designed specifically for managing BBS (Flamingo Set; Medwork, Hochstadt, Germany) in a large patient cohort. They reported successful extraction in 96.4% of cases, with a mean procedure time of 22 minutes, an adverse event rate of 12.7% (including bleeding, perforation, gastroesophageal laceration, and sepsis), and an 83% success rate for placing a new device (4. However, various devices not specifically designed for this purpose have been used successfully, as in the case of our patient, where a combined endoscopic technique with laparoscopic instruments was employed effectively.

To prevent complications following PEG placement, it is crucial to begin at the time of the procedure by correctly positioning the external bumper, leaving at least 1 cm of space from the skin. Once the ostomy has formed and healed, caregivers should be instructed to advance and rotate the tube 360 degrees and ensure the external bumper is correctly positioned (1 cm from the skin). Avoid placing gauze or dressings between the skin and the external bumper, as they increase traction; additionally, ensure that the passage of food is not forced. These care strategies are essential to reduce the risk of this syndrome (3,7,10-12. A proposed management algorithm is outlined based on the established diagnosis (Figure 8).

Conclusion

PEG is a widely used method for nutritional support, and BBS is a condition that should be suspected when there is difficulty in feeding and local signs of inflammation. Endoscopic management is feasible in most cases, and the use of laparoscopic forceps through the channel is a more accessible alternative in settings where specific instruments for completely releasing the buried internal bumper are not available.

text in

text in