Introduction

Language pedagogy often focuses on proficiency-based practices that prioritize communicative and linguistic competence as the primary -and often only- objectives in language classrooms (Huebner & Jensen, 2008; Tschirner & Heilenman, 2011). Recently, research has drawn attention to the social dynamics that inform language learning experiences (Norton & Toohey, 2011), prompting a reevaluation of pedagogical practices in order to reflect classroom objectives that take a more critical and socially oriented approach to language instruction. Such an approach not only centers linguistic proficiency, but also emphasizes the importance of connecting learning experiences to communities outside the classroom, as well as understanding the socio-political nature of language use. While service learning (SL) as an instructional model appears to align with this pedagogical approach (Grim, 2010; Bettencourt, 2015; Moreno-López et. al, 2017), the question of how to effectively implement SL into curricula in a relevant way remains a challenge for educators.

This exploratory paper examines the role of SL for second (L2) and heritage language (HL) learners of Spanish, and how SL impacts learner beliefs, attitudes, motivation towards language learning, as well as their ability to connect their experiences to course content. One emergent theme among this study findings is the evaluation of SL experiences through a strictly proficiency-based lens. Given these findings, suggestions for shifting away from an exclusively proficiency-based focus in language curricula are offered in order to give more overt attention to the socio-political aspects of language learning so that learners may develop an awareness of the benefits of SL and be able to better connect it with their own language learning experiences.

Learner Motivation and Attitudes

Given that SL can play a role in the affective aspects of language learning, attitudinal studies are critical for evaluating the effectiveness of this pedagogical model. The study of learner attitudes is a long-established line of inquiry; Gardner (1985) has looked extensively at affective aspects of L2 learning, and how attitudes and motivation connect with achievement. Ushida (2005) similarly examined motivation and attitudes, though in an online L2 course, and found that -like a traditional face-to-face setting- motivated learners with positive attitudes generally studied more regularly and took more opportunities to improve their language skills. Motivation can also inform actual learning and acquisition outcomes: in Grey's and Jackson's (2020) study on the connection between learner perception/affective factors and learning outcomes, participants learned new L2 vocabulary and its grammatical gender, and were then evaluated on their objective and perceived ability to produce this vocabulary with the correct gender was evaluated. The authors found that learners' subjective perceptions were, in fact, significantly and positively correlated with actual linguistic accuracy. However, it is also worth pointing out that because motivation and attitudes are typically rooted in learners' individual traits and positionality, Dörnyei (1994) argues that it is also critical to reflect on how educators can motivate learners, suggesting efforts such as encouraging a sociocultural component in the L2 syllabus, developing learners' cross-cultural awareness systematically, learners' instrumental motivation and students' self-confidence, and also promoting favorable self-perceptions of competence in the L2.

SL as a Critical Approach to Teaching Language Learners

Functional proficiency has long been the center of language classrooms. While this remains a prominent approach to teaching HL/L2 classes, the last few decades have seen a critical reexamination of this goal (e.g., Osborn, 2006; Norton & Toohey, 2011; Johnson & Randolph, 2015; Randolph & Johnson, 2017), where educators are now advocating for a social justice approach to language teaching and recognizing the sociopolitical nature of language that exists inside and outside the classroom. Here, social justice refers to "members of a society sharing equitably in the benefits of that society" (Osborn, 2006, p. 16). In language education, this involves educators evaluating prevailing pedagogical approaches and practices to reflect intercultural understanding as a key goal in language classrooms. This requires instructors and students to make concerted efforts to foster inclusivity, empathy, consider their own positions of privilege when discussing culture and engaging with different communities, and promote dialogues that "include marginalized voices not as an added component, but as an integral part of the knowledge about the world" (Senel, 2020, p. 65).

Given the global and intercultural focus that is often present in language instruction, social justice-oriented pedagogy may seem to align almost naturally with language curricula. However, its implementation has various challenges with regard to planning logistics as well as finding ways to ensure that the spontaneous and unscripted moments that make up the SL experiences are relevant to classroom learning. This requires intentional work on the part of educators and learners, and involves a thorough deconstruction of sociopolitical, linguistic, and cultural power structures that permeate even within educational institutions and course curricula (Randolph & Johnson, 2017). In a statement on diversity and inclusion issued by American Council for the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL), such goals can be achieved through "leveraging and maintaining meaningful connections with diverse communities" (ACTFL, 2019). While there are certainly a variety of ways to establish such connections outside the classroom, one of the more increasingly common methods has been incorporating SL to course curricula.

As an educational approach, SL aims to provide students with opportunities to instill a positive impact on a community while applying new knowledge and honing their developing skills outside a classroom environment. Although SL can be performed in various ways, students typically interact with and serve a specific community in order to enact positive societal change in that community, as well as accomplish specific learning goals in the classroom. While results at the community-level are often transparent -such as a SL project involving after-school tutoring resulting in improved student grades- the results for students enrolled in SL courses are not always transparent. Studies on affective and attitudinal outcomes for language learners show that SL can increase students' self-confidence in their L2 skills (Grassi et al, 2004; Hummel, 2013), their overall attitudes towards language learning (Zapata, 2011), and provide a greater sense of having an active role in their language education (Grim, 2010). HL learners may also experience similar benefits, but they have also been shown to be in a unique position to use their own ethnolinguistic knowledge as a resource at SL, and successfully doing so further improves their motivation to develop their HL skills (Pascual y Cabo et. al, 2017). In an advanced learner context, Llombart-Huesca and Pulido (2017) showed that SL provides many HL learners with an opportunity to not only revisit their own personal experiences from an outsider perspective, but also discover communities beyond their own. Additionally, in a recent study, Pak (2020) examined the long-term benefits of SL on learners of Spanish, and found that for many learners, SL stood out as one of their most significant educational experiences in college, even as seventeen years after their SL experience. Long-term benefits to SL may also extend beyond positive attitudinal changes; recent studies have also found that for many learners, positive attitudes towards SL and thus language study may go so far as to impact learners' career choices, drawing them to work with populations that speak the target language (TL) (Osa-Melero et al., 2019). In the case of SL projects that involve teaching in some capacity, learners gain a better understanding of the teaching profession and may pursue an educational career (Salgado-Robles & Lamboy, 2019).

A great deal of research has also looked at the linguistic and cultural benefits that can be attributed to SL. In terms of linguistic outcomes, SL projects appear to aid in vocabulary learning, as illustrated in Tocaimaza-Hatch and Walls (2016), where learners completed English-to-Spanish translations of signage for a local zoo, and both L2 and HL learners demonstrated improved vocabulary. This is further evidenced by Tocaimaza-Hatch's (2018) study in which learners participated in a story time program with bilingual children and were later able to retain new vocabulary learned in SL sessions. More recently, Salgado-Robles and George (2019) investigated the development of Spanish region-specific pronouns, vosotros and ustedes, among HL learners who were of Mexican descent but studying abroad in Spain. Findings showed that learners who engaged in SL projects during their study abroad period increased their use of vosotros two times more than students who did not participate in any SL projects.

Development of intercultural competence is perhaps one of the most critical benefits of SL engagement, where learners can development self-awareness of their own cultures, and also become more aware of the issues surrounding Latinx populations in the U.S., particularly those which are local to learners' communities (Rodriguez-Sabatar, 2015); Moreno-López et al. (2017) conducted a study that looked at SL implementation across different learning formats (face-to-face, online, study abroad), and found that learners generally indicated positive attitudes towards SL in the sense that it not only improved their L2 acquisition, but also enhanced their curiosity about different cultures more than their non-SL counterparts.

Despite the benefits of SL evidenced by current research, the effective incorporation of SL into language curricula presents challenges. Logistical considerations include whether certain sites of SL are prepared for working with student populations, as well as how much communication and training by such sites of SL are required (Rosing et al., 2010). Learners' needs must also be taken into account (Carracelas-Juncal, 2013), as L2 and HL learners represent diverse backgrounds that may impact the positionality of each learner within the community that they are serving. Differing levels of student's linguistic proficiency may also play a role in the effectiveness of SL, as evidenced by Zapata's study (2011) in which more advanced intermediate learners appeared to benefit more than lower intermediate learners, suggesting certain degree of preexisting proficiency may be required to successfully participate in SL projects that require the use of the TL. Finally, because SL projects must support course-specific learning outcomes, these outcomes must also be thoughtfully defined so that classroom learning and SL experiences align with these outcomes (Bettencourt, 2015).

Present Study

Given the challenges involved in implementing SL, it is crucial to reflect on best practices for its application in language classrooms. While research addresses this in the context of Spanish learners, few studies examine SL among advanced learners enrolled in content courses, which is the focus of the present study. Here, we look at learners' experiences with, as well as their beliefs and attitudes towards SL, assess their ability to derive meaning and relevance from their SL projects, and reflect on how these projects can best be incorporated into HL and L2 curricula in order to foster more beneficial experiences for students. As such, this study is guided by the following questions: (1) How does SL impact advanced learner motivation in terms of studying Spanish in and outside the language classroom? (2) Does this motivation -as well as attitudes towards Spanish and SL- change over the course of a semester? (3) In what ways are advanced learners able to connect their SL experiences to course content?

Participants1 and Setting

This study was conducted at a small liberal arts college in a rural town in the U.S., where approximately 75% of the alumni was identified as white, and under 4% as Hispanic/Latino (Data USA, 2019). It took place over one semester, with students enrolled in two sections of an upper-level introductory Spanish linguistics course, both of which I taught. Although 19 students signed up for these sections and completed the tasks involved, participate. Project options included (1) a local ESL adult program, where participants were placed in an ESL classroom and worked one-on-one with adult L2 learners of English who were 18 age or older, all of whom were native Spanish speakers, while a lead instructor guided the whole class; (2) an after-school program working with elementary school students, grades K-5. Here, all elementary school students were native or HL speakers of Spanish, their ages ranging from 5-11 years old. This program also focused on developing bilingual competencies, and so participants were expected to equally divide their time at each session between activities in Spanish and English. Table 1 summarizes participant information:

Table 1 Participant Background

| Participant Code | L2 or HL Learner | Year | Major or Minor in Spanish | Enrolled in other Spanish Courses | Further Study in Spanish | Prior SL Work | Tpe of SL Work |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | L2 | soph. | yes | no | yes | no | Elementary |

| B | L2 | soph. | yes | yes | yes | yes | Adult ESL |

| C | L2 | soph. | yes | no | yes | yes | Elementary |

| H | L2 | junior | yes | yes | yes | yes | Adult ESL |

| I | L2 | soph. | yes | yes | yes | no | Adult ESL |

| J | L2 | soph. | yes | no | yes | yes | Elementary |

| K | L2 | soph. | yes | no | yes | no | Elementary |

| M | HL | freshman | yes | no | yes | yes | Elementary |

| N | L2 | soph. | yes | no | yes | yes | Elementary |

| O | L2 | soph. | yes | yes | yes | no | Elementary |

| P | HL | freshman | unsure | no | unlikely | yes | Elementary |

| Q | HL | senior | yes | yes | yes | yes | Adult ESL |

| T | HL | junior | yes | no | no | yes | Elementary |

SL sessions ran for 12 weeks and took place on the participants' campus, where they met with the same program partner for each 2-hour session. At ESL sessions, participants were expected to assist adult learners with grammar, pronunciation, and vocabulary lessons given by the lead instructor, usually in the form of specific written and oral exercises assigned by the instructor, and SL participants served as practice partners to ESL learners. While English was the language of instruction, participants were paired with Spanish-speaking ESL learners so that Spanish could still be used to help facilitate communication. At the after-school program, participants did a mix of activities with their students, ranging from games, arts and crafts projects, reading books, playing outside, and completing homework assignments. The coordinator of this program, who was present at all sessions, also required designated time in Spanish; this was usually reserved for reading time.

Tasks

Participants completed weekly tasks, which included the following: (1) a background questionnaire that detailed participants' experience with Spanish (see Table 1); (2) a Likert-scale questionnaire that participants completed three times during the semester -beginning, middle, and end- in order to track changes over time. This questionnaire measured their motivation to learn and use Spanish outside the classroom, as well as their attitudes towards SL in terms of its relevance to learning Spanish; (3) 9 electronic journal entries that invited participants to reflect on specific aspects of their SL experiences or to connect these experiences with specific course content. For the latter, these e-journal assignments were timed so that participants could complete them after concluding the relevant unit in the course; for example, participants wrote about observable syntactic features only after discussing this topic for several weeks. Participants completed these entries in Spanish; however, in the interest of conserving space, only English translations will be presented in the results.

Analyses

Because this study is based on a small sample of participants, the questionnaire data is examined at the descriptive level, and is further supported by the e-journal data, which represents the primary source for the present analysis. Using NVivo 12 (2018) for coding e-journal responses, e-journals are analyzed by means of qualitative content analysis (see Mayring, 2004). Through this approach, analyses are derived directly from text data, focusing on both explicit and latent content. By way of this qualitative approach, emerging themes were identified through an initial review of participants' e-journal responses and were subsequently used for creating thematic categories for organizing data in a second review. A third review of data -this time by participant - focused on notable changes that occurred over the course of the semester for individual participants. This holistic approach is particularly advantageous for the scope of this exploratory study; first, because the focus remains on learners' varied perspectives, relying on their own understanding of their SL and classroom learning experiences. Additionally, this approach allows for cross-comparisons of participants regarding specific themes and can also bring to the foreground a variety of factors that may contribute to learners' distinct perspectives. Finally, part of the analytical approach employs positionality theory, which takes an individual's point of view as informed by multiple overlapping identities that are fluid and informed by power dynamics (Kezar, 2002). Thus, such a framework highlights how identities impact the way individuals are perceived in the context of SL interactions.

Results

Initial Attitudes and Expectations Towards SL

Before beginning their SL projects, participants filled out a background questionnaire, which included two attitudinal questions relating to SL:

How do you feel about participating in a SL project as part of this course?

What are your initial expectations of what you will be doing in this SL project and/or how it will be relevant to your experience in this course?

Participant responses varied: in a few cases -specifically, Students B, J, and K- participants were indifferent or commented on the time commitment involved, such as J, who indicated that it does "take up a lot of time." The majority of the participants, however, expressed positive sentiments towards SL, citing that it would be beneficial to their own learning processes, as illustrated by Students A and C, who commented, respectively, that SL would be a "great way to track learning progress of students" and "interesting way to improve language skills." Only one student, however, responded to this question with any reference to potential community benefits as a factor influencing their attitudes towards SL: "I think it's a pretty cool idea, it makes my work and time feel valued and put towards something great" (Student T).

For the second question, responses once again varied when reflecting on their own expectations of their upcoming SL project and its connection with the linguistics course in which they were enrolled. Few participants made direct connections between SL and course content. Student A, for instance, offered a detailed response regarding their expectations working with an elementary school child:

I believe I will learn more about the Spanish language amongst youth from native Spanish-speaking families. I will be able to apply what I have learned in my linguistics courses to understanding the process of speaking a second language, and how bilingualism creates both academic progress as well as challenges amongst youth students.

Here, Student A reflects on the possibility of learning more about the Spanish language, instead of expressing an expectation of improving their proficiency. They also connect the experience of working with a bilingual student with the content of the course; specifically, L2 learning and bilingualism. Several other participants, like Student C, made more general comments about language-related expectations, often expressing an expectation of developing their own language skills throughout the SL process: "It is good practice for learning Spanish, and speaking to and with native speakers." Only three participants -K, N, and P- explicitly stated that they did not perceive any foreseeable connection between SL and course content. For instance, Student N responded that:

I expect to enjoy it; however, I don't know if it will relate to this class. I have been assigned to the kindergarten level, and they are still learning about the language, so it may be more difficult for me to find connections to the course.

For Student N, the young age and stage of linguistic development of their assigned student are indicators that they will not be able to relate their SL experiences to the course content, suggesting a perception that the course content is only applicable to more advanced native Spanish speakers. As shown in these examples, participants' expectations of SL are viewed from the outset from a competency-based perspective.

Likert-scale Questionnaires

This questionnaire consisted of statements relating to participants' motivation to study Spanish, their confidence in their own linguistic abilities, their attitudes towards studying Spanish, their efforts towards learning Spanish, and their attitudes towards SL in a language course. Because a Likert-scale of 1-5 was used for this questionnaire (1 = totally disagree; 5 = totally agree), this section focuses on participants' numerical average for each statement and how these averages changed across the semester.

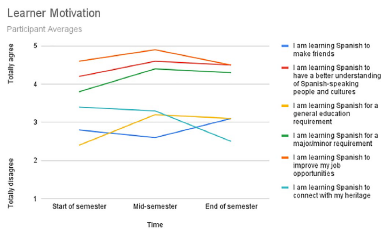

In terms of participants' motivation to study Spanish, the questionnaire statements listed a variety of possible factors (shown in Figure 1), each of which weighed differently among participants.

Among the stronger motivators for participants were satisfying a major/ minor requirement, developing a better understanding of Spanish-speaking people and cultures, and improving prospective job opportunities, all of which remained consistent factors throughout the semester. While participants' averages for each statement did not vary significantly over time, none of these factors appeared to be definitively unimportant, since most students did not choose to disagree with most statements.

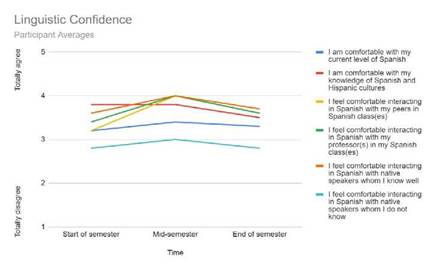

Next, participants evaluated their level of comfort with their own abilities in Spanish and knowledge of Spanish culture, as well as using it in different contexts and with different interlocutors, such as peers, professors, and native speakers whom they know and do not know. Figure 2 below summarizes participants' response averages.

As shown above, there is less agreement with these statements, and less variance - where average responses generally stayed between 3 ("neither agree nor disagree") and 4 ("agree"). Participants further indicated feeling significantly less comfortable interacting with native speakers of Spanish whom they did now know (averages of 2.8, 3, and 2.8, respectively) in comparison to other interlocutors with whom they may feel less social distance.

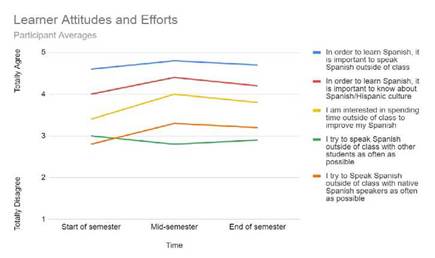

This questionnaire also included statements regarding learners' attitudes and beliefs about language learning, particularly related to the effort required to successfully learn a language. Specifically, participants responded to statements about speaking Spanish outside the classroom, their willingness to do so, their valuation of culture as a component of the language learning process, as well as their own perceived efforts to speak Spanish outside the classroom.

In general, participants showed strong agreement with the generalized statements on learning about the culture and speaking Spanish outside the classroom, although it is worth noting that, while participants seem to recognize and value the importance of these components, participants were more neutral about their personal interest or motivation to make the effort to use Spanish outside the classroom, and even less so regarding actual efforts to practice Spanish outside the classroom. It is also with these statements that participants show some general change over time, with participants agreeing most strongly with most of these statements at the end of the semester.

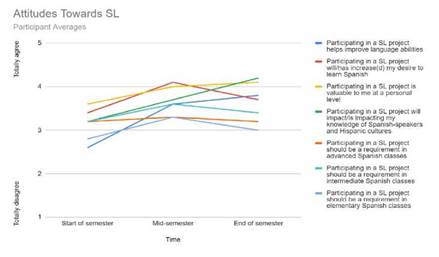

Finally, the questionnaire also looked at participants' attitudes towards SL in terms of how their SL experiences were valuable to them, as well as how valuable SL is for language learning at different levels of proficiency.

In terms of experiences with their SL projects during the semester, participants were generally neutral towards statements that connected SL to linguistic abilities, both improving them or being motivated to improve them, though participants did appear to agree slightly more with these statements by the end of the semester. When it came to evaluating non-linguistic components of SL -such as valuing the experience on a personal level and improving one's cultural understanding- participants seemed to value these connections more as important aspects of SL, which also increased by the end of the semester. Regarding the general importance of SL in language classes, participants maintained a relatively neutral stance towards implementing SL in Spanish classes of all levels. Finally, one interesting observation that can be applied to almost all the statements in the questionnaire is that, on average, participants agreed more strongly mid-semester than they did at either the beginning or end of the semester.

E-journals

This section focuses on participants' responses to weekly writing prompts, which centered around two themes: first, their beliefs and attitudes towards SL, and second, their ability to connect course content to their SL interactions. A number of key themes emerged that will be discussed in turn; namely, connecting participants' SL experiences with course content, gauging successful learning by strictly proficiency-based standards, and gauging successful learning by other standards.

Writing prompts that focused on course content instructed participants to reflect on specific linguistic features they observed in the student with whom they worked and reflect on any observable linguistic features that presented challenges to their students in either English or Spanish and the possible causes of those challenges. Participants were able to identify a variety of linguistic features in their students' speech throughout the semester, though earlier writing prompts often included less precise descriptions:

I noticed differences in the pronunciation of 's.' I know that there aren't words in Spanish that start with 's', only words with 'es.' So, there is a bit of an 'e' sound in words that start with 's.' - Student M, e-journal 1

(...) the sound of 'u' /oo/ (in Spanish) but in English it's like /uh/ and they have some problems learning that. The sounds that are a combination of two consonants are more difficult like in 'aught', in 'daughter' and 'thought.' - Student I, e-journal 1

In these examples, Student M referred to consonant clusters that do not appear in word initial position, such as /sp/ and /st/, and are typically preceded by the vowel /e/. For the same writing prompt, Student I similarly identified pronunciation features of their student, but used imprecise descriptions of Spanish and English phonemes, and mistakenly referred to diphthongs as a group of two consonants, rather than vowels. However, these descriptions became more accurate as the semester continued, as evidenced by a later e-journal entry of Student I:

For English, there are some things that are more difficult to pronounce like the diphthong 'ou' en words like 'bought' and 'sought.' I think that these sounds and phonemes do not exist in Spanish and so it's difficult for them to say them in English. Also, another thing is when they say the sound 'es' before words like those that start with 'st' like 'study.' For example, some students say 'estudy' or 'estudent.' - Student I, e-journal 3

Here, there is a notable difference in Student I's observations regarding pronunciation, where similar observations are made as those in e-journal 1, yet e-journal 3 presents more description and greater accuracy, identifying vowel clusters in the same syllable as diphthongs, as well as noting students' transference of Spanish phonological rules to English. Participants' observations also extended to other types of linguistic features at different times of the semester, including morphological observations:

Often when I'm speaking with my ESL student, they've used words that I didn't know. This past week she said 'tetera' and I was confused for a couple of seconds, but I know that 'té' is 'tea' and the suffix 'era' or 'ero' is something related to this. So I was able to figure out the meaning of their sentence. - Student B, e-journal 5

Beyond making observations about their ESL student's speech, Student B explained their own experience of extrapolating meaning based on their existing lexical and morphological knowledge, the latter of which was discussed in class the week prior to this particular e-journal entry.

While several of the writing prompts focused on observing different types of linguistic features of the students with whom they worked, participants also connected their SL experiences to sociolinguistic components of the course; specifically, discussions relating to Spanish in the U.S.:

The class helps my perspective on Hispanic culture, historically, which I think is interesting and very complicated. The part of the class that talks about Spanish in the United States also has had an impact on my perspective on Spanish speakers in the states, like my student. I understand more because my student doesn't have an interest in Spanish and only wants to speak in English, because he has the mindset that English is the primary language and it's more accepted by society. -Student A, e-journal 8

Near the end of the semester, the course shifted to a discussion of Spanish as a HL in the U.S. In this entry, Student A commented on their own student's unwillingness to use Spanish -a frequent comment among participants who worked with the bilingual tutoring program for elementary school students- and connects this with language attitudes.

When reflecting on whether they benefited personally from their SL experiences, one common tendency was to measure their success and the overall efficacy of SL by proficiency-related standards. In some cases, participants indicated that they did not personally benefit from the SL program because their own Spanish did not improve. This was especially the situation for those who participated in the bilingual tutoring program and worked with children -many of whom were reluctant to use Spanish. Students J and K, for instance, indicated that they enjoyed the SL experience, but did not feel that their Spanish improved in any way:

I don't think I benefited from this project when talking about my Spanish abilities. I can't practice my Spanish much with small children because they don't know a lot of Spanish yet (...) although I can practice a little vocabulary with them while I read books to them (...) In general, I've enjoyed my service project because it's fun, but I don't think that my abilities in Spanish have improved. - Student J, e-journal 6

I think it (SL) has taught me how to treat children more than learning Spanish. A lot of times the kids don't speak Spanish unless they're forced to. Also, the Spanish that they read aloud in books is elementary Spanish, so that's why my vocabulary hasn't expanded much. - Student K, e-journal 6

As these two participants point out, their specific SL experiences -working with young HL speakers- did not place them into significant contact with Spanish, which in turn meant that the experience itself was not contributing to improving their own linguistic proficiency. In other cases, some participants similarly used proficiency-based standards for gauging their SL projects, but instead reflected on how they benefited from being exposed to different varieties of Spanish:

In school, the professors usually speak with perfect accents and very slowly. But in the ESL classes this isn't the case, and so I think that I am developing an ability to hear more informal Spanish. - Student I, e-journal 6

(...) I can improve my level of Spanish because I'm learning a very relaxed register in contrast to the register in a Spanish class. It's very interesting to see the forms of speech in (the tutoring program) because it's very informal and I like that arrangement because it's more real. -Student O, e-journal 2

Students I and O participated in the adult ESL program and the elementary school tutoring program, respectively. In both instances, these participants were conscious of the different varieties of Spanish they were being exposed to through their SL participation, in particular, more informal varieties not often heard in their language classrooms. For these participants, that exposure contributed to improving their own linguistic proficiency and was seen as an important benefit to their SL experiences.

Beyond connecting SL experiences to improving one's proficiency and seeing this connection as an important factor in determining the success of the SL program, few students noted other factors that contributed to their successful SL projects. Some indicated that they had developed meaningful connections with their students:

I've enjoyed the relationships that I'm making with the adults from ESL, and I wouldn't have had these relationships without a high level of Spanish. Because of that, I think that it's giving me more motivation to learn Spanish. -Student H, e-journal 2

Here, Student H reflects on the relationships they were able to cultivate during their SL sessions, but also indicates that having a high level of proficiency helped facilitate that, suggesting that perhaps this type of SL might not be as beneficial to students with less proficiency. Other participants commented on be able to develop social, cultural, and/or political awareness and empathy through their SL participation:

I definitely think that it (SL) has made a positive impact because these people are very educated, but they don't speak English, and so they are very limited in terms of jobs. But with English they can find work that is better and pays well. -Student I, e-journal 8

I haven't learned much about the Spanish language, but I have learned a little about problems for Hispanic Americans and legal documentation. During the semester, the father of my student was arrested by ICE. I don't think this could be such a big problem, or that it could ever happen (here) (...) my perspective about the lives of children has changed a bit because now I know that some children don't have an easy life. A lot of the parents work a lot and it's difficult for the parents to raise their children and earn sufficient money. -Student J, e-journal 8

Here, Student I highlights the benefits of the adult ESL program, pointing out the linguistic capital that English carries in the U.S., and the professional opportunities that become available to those who can speak it. Student J, on the other hand, reflects on their student's experiences with ICE, and how this shed light on some of the critical issues faced by numerous members of the Latinx community in the U.S. While Student J previously noted not having benefited from SL in terms of developing linguistic abilities (which they repeated in the above excerpt), here, they highlight their interaction with a significant socio-political facet of language learning; specifically, larger, macro structures that work against marginalized identities. Finally, in the case of HL speakers, some of these participants also remarked on how SL allowed them to connect with their heritage:

I've enjoyed this service project a lot. For me, it's not just about improving my Spanish, it's about making new friends outside (the university). Being far from home, I sometimes find myself sad because I can't be with my family, but at least spending time with people who know what I'm talking about makes me feel better. I feel connected to home, just by speaking Spanish. Also, the people (ESL learners) can understand my culture and I can share it with them and they with me. -Student Q, e-journal 6

In this excerpt, Student Q immediately states that improving their abilities in Spanish was not their goal when embarking on this SL project, but rather, was more interested in forming relationships. Moreover, Student Q alludes to homesickness and perhaps a certain degree of loneliness, but then goes on to explain that participating in this SL project helped to quell these feelings, in that they regularly spoke Spanish with and formed friendships with other members of the Latinx community.

Discussion and Final Remarks

One of the central questions that this study seeks to address is how SL impacts advanced learners' motivation to study Spanish in and outside the language classroom. The results show a good deal of variation among participants in terms of their motivation before, during, and at the end of their SL projects, particularly with regard to motivations to study Spanish. By the end of the semester, however, participants generally agreed that SL had increased their motivation to learn Spanish, that it had been valuable to them at a personal level, and that it helped them learn more about Spanish speakers and Hispanic cultures, thus aligning with previously cited findings (Grim, 2010; Zapata, 2011). It is, however, worth noting that for nearly all questionnaire statements, participants' agreement average generally increased at mid-semester before decreasing and approximating the responses from the beginning of the semester. This mid-semester spike could be attributed to participants becoming accustomed to the demands of SL participation, while a dip in motivation and attitudes at the end of the semester may be the result of the fatigue that is not at all uncommon during a time when students are encumbered with final exams and other end-of-semester obligations.

Additionally, while some participants indicated indifference about their anticipated experiences or doubt regarding the extent of their own benefits from participating in SL, it was evident that some of these participants were still able to connect their SL experiences to course content, even if they did not necessarily recognize those learning moments as beneficial. More than connecting their SL experiences to the analysis of specific linguistic features, participants were also able to connect SL to other aspects of language learning, such as being able to recognize the social aspects of bilingualism, as well as the status of Spanish in the U.S., which in turn further supports the idea that SL can lead to linguistic and cultural gains (Tocaimaza-Hatch & Walls, 2016; Tocaimaza-Hatch, 2018; Salgado-Robles & George, 2019). Additionally, participants demonstrated a development of cultural awareness and empathy throughout the course of their SL projects. Such observations, however, are limited, in part because several participants consistently considered the primary goal of a language class to be proficiency, and thus also that of their SL experience. While some participants felt that their increased exposure to other varieties of Spanish was a means of improving their proficiency, others felt that they did not use enough Spanish to increase their proficiency, which made their SL experiences not beneficial to themselves, although several acknowledged that they were still beneficial to the local community. Additionally, the limited extent to which learners were able to connect their SL experiences with course content may also be the result of being presented with limited reflection opportunities. While learners engaged in multiple modes of reflection activities, in-class reflections were limited to three discussions over the course of the semester,2 and more frequent guided discussions could have helped students make these connections more easily.

Such findings raise a number of new issues regarding best practices in SL as well as in language teaching. First, as evident among participants who worked with young HL speakers in the elementary school bilingual tutoring program, it is crucial to examine how instructors and students perceive authenticity in a speech community, and what learners' expectations are when engaging with this community. Specifically, students may feel that their SL experiences are not meaningful to their growth as language learners unless they are engaging heavily in the TL during their SL interactions. However, speech communities may not exclusively use the TL, such as in the case of the elementary school children who were either native or HL speakers of Spanish but resisted using Spanish in their interactions. However, this linguistic behavior does not make these interactions any less relevant to the learning experience. Working with young, bilingual students -some of whom may dislike using Spanish or hold negative attitudes towards it- is certainly an important experience for adult L2/ HL learners, as it highlights an important Spanish-speaking demographic that might otherwise be overlooked in courses that focus on monolingual speakers' Spanish. As instructors, it is crucial to make language learners understand that the authenticity of a speech community need not consist solely of monolingual Spanish-speaking communities, but of diverse groups of monolingual, bilingual, and multilingual speakers with varying attitudes and levels of Spanish proficiency, all of whom fit into the broader category of "authentic communities". Therefore, engaging with these communities often involves, but does not necessarily involve, interactions in TL. Moreover, differences in the way authenticity is perceived also highlight differences in the position of learners, teachers, and community members, which in turn can inform distinctive linguistic attitudes and learning goals.

This also raises the question of how language educators should frame their pedagogy so that learners can still appreciate the value of SL experiences that involve varying and sometimes limited exposure to the TL. In order to achieve this, it is crucial to reevaluate language pedagogy on multiple levels. Currently, language curricula are often designed in such a way that linguistic proficiency is highlighted as the sole objective; this is evident when we consider the focus of learning objectives that are often set within any given language curriculum: proficiency-related objectives are often delineated in great detail, focusing on the development of different proficiency skills and how such goals are achieved. In contrast, objectives relating to intercultural competence and the connections between language learning and social justice are often brief and ambiguous. Language teachers may therefore consider adopting more concrete and specific language that goes beyond a general "intercultural competence" objective, such that these objectives have as much space as the proficiency objectives.

Additionally, it is crucial that both teachers and students have clear and similar conceptualizations of intercultural knowledge in a language program and how it forms an integral part of language learning, as well as how specific SL projects can contribute to the development of this knowledge. Furthermore, implementing SL in language classrooms and shifting away from proficiency-centric practices also requires that this be done at a broader curricular level. In other words, SL -along with other course components that do not necessarily focus on developing proficiency- often function in a space separate and decontextualized from their language programs and non-participating faculty. Specifically, the objectives we tend to set relating to building community connections and cross-cultural knowledge (often achieved through SL) are not reflected in other aspects of the curricula, such as assessments, which tend to be focused on proficiency (and accuracy). Without this curricular overhaul, SL -along with intercultural knowledge and social justice- will continue to exist as an exceptionalized entity that is at odds with proficiency-based instruction, reinforcing this dichotomy, rather than promoting an amalgamation of equally important learning components.

While this study has examined the role of SL for advanced learners of Spanish, there are various limitations that restrict the scope and the conclusions that can be drawn from this study; for example, participants were allowed different options for their SL projects -both of which were pre-existing programs organized by the university-in order to maintain some flexibility with completing a time-dependent task. This, in turn, presented challenges in terms of finding ways to incorporate distinct SL experiences in a relevant way in the classroom, as well as prompting students to reflect on their experiences. For instance, the course in which participants were enrolled had addressed Spanish as a HL, but not until very late in the semester when participants had nearly finished their SL projects. As such, some of the participants working with HL speakers may have had difficulties connecting their experiences to language learning. These results prompt a critical examination of prevailing pedagogical approaches, where instructors not only ask whether a curriculum aligns with pedagogical goals themselves, but also questioning whether these objectives need to be recalibrated to fit the valuable extralinguistic experiences that have been incorporated inside and outside of language classrooms.