INTRODUCTION

In order to perform diagnosis and treatment plan for a patient, it is necessary to evaluate soft and hard tissues both at rest and in function. Smile analysis is therefore important as it is connected to esthetics and to the skeletal position of the maxillary and dental structures on the three planes. (1 Smile evaluation can be approached from different perspectives and is different for each individual: Sarver and Proffit2 describe the non-posed smile as dynamic and involuntary, expressing genuine human emotions with participation of all muscles of the facial expression. In contrast, a posed smile is voluntary and not accompanied by emotions. It is static, as it can be maintained. They also describe the smile as forced, which is tense and unnatural, or unforced, which is voluntary and natural.2

In adults, according to gingivae and teeth exposure, the smile can be classified as: high smile, which shows the total length of upper front teeth and their adjacent gingiva band; medium smile, which shows 75 to 100% of the upper front teeth and the interproximal gingiva only, and low smile which shows less than 75% of anterior teeth. (3

Although there are no available guidelines for assessing children’s smile, the gingival smile is frequently accepted as normal: “kids show more teeth at rest and more gum at smile than adults”.4 Similarly, Sarver and Ackerman5 suggest that the gingival smile decreases with age. Van der Geld et al 6 and Desai et al 7 also concluded that gingival and dental exposure decreases with age. Therefore, a high smile type is more common among children and young people than among adults (8)(9

Despite the importance of smile in our society and the increased emphasis in esthetics, and although aesthetic diagnostic criteria have been established from the fields of orthodontics and prosthetics,10)(11)(12 una búsqueda en la literatura odontológica muestra que los datos científicos son escasos y casi nulos en la población infantil.

Therefore, the purpose of this research project was to understand the characteristics of smile among children in deciduous and mixed dentition with normal occlusion, in order to compare differences in the perioral soft tissues observed in the studied population, according to patients’ teething stage and gender. This project will lay the foundations for a database of smile in children with normal occlusion that will later serve, among other research projects, to find out if there are differences in terms of perioral soft tissue among different malocclusions.

METHODS

A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted in children aged 3 to 12 years. 1,100 children were evaluated and 122 were selected by convenience as they met the general and occlusal inclusión criteria described in Table 1, which defines normal occlusion in children.13

Patients and their guardians were informed about the study’s objectives, requesting their participation and signing an informed consent. This study meets the ethical requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki (2008) and of Resolution 8430 of the Ministry of Health on research with human beings.14)(15

Each child was subjected to clinical evaluation, registering occlusal and facial data and sorting them out into the established groups according to gender and dentition type (deciduous, early mixed, silent mixed or late mixed). Then each was recorded a video clip using a standardized technique according to Sarver and Ackerman.5 This methodology was based on the most current protocols, which have been validated by different authors.1)(3)(5)(16 The video clip was framed on the first frontal plane of the face, obtaining images at rest and of posed and unforced smile. A high definition video camera was used (Canon Vixia HFM-300) with spotted artificial lighting, fixed distance and height according to each patient, as well as a cephalostat to control head position. The portable Siemens cephalostat adapted for this project included graph rulers framing the face of the patient in order to ensure a 1:1 ratio, as well as a metal base with a rack, a lever for leveling height, and wheels for transportation (Figure 1).

Each child stood on the cephalostat with the head stabilized to the Frankfort plane parallel to the floor, and vertically along the middle facial line. The 60 s video clip was always recorded by the same operator, starting with the child at rest until achieving a posed non-forced smile, according to the protocol described by Ackerman and Ackerman.17

The video clip5, 17 was recorded as Full HD 1080 p (H264, 60i fps) with automatic white balance. All the information was saved on a desktop computer (Intel® CoreTM i5-2300 CPU @ 3.00 GHz 2nd gen, 4 Gb RAM, NVIDIA® GeForceTM 9500 GT 1 GB DDR3 Graphics, HDD 1 TB @ 7200 RPM), and each video clip was exported to a video editing software (Adobe Premiere Pro CS5), allowing observation of fixed individual images. Two observers simultaneously selected the photograms that best depicted a posed unforced smile. These photograms were manipulated in a photo editing software (Adobe Photoshop CS5) to adjust 1:1 scale, locate the points and perform measurements with precise accuracy, according to the default protocol summarized like this: the video clip is imported into Adobe Premiere to extract the photogram of the patient’s smile and then it is exported as a .Jpeg file with a resolution of 1920 x 1080 pixels; then it is processed at a máximum depth and with square-pixel to 1.0 (each photogram should have a resolution of 96 pixels per inch). Each photogram is opened in Adobe Photoshop, verifying that image size is 72 pixels/inch in resolution and is adjusted to 1:1 ratio. Measurements are made and entered in the corresponding table.

Figure 2 shows the line reference system used to measure the variables, as used in previous studies. (1)(3)(5)(16)(17

Figure 2 Line reference system. 1. Length of upper lip; 2. Thickness of upper lip; 3. Thickness of lower lip; 4. Height of corners; 5 Intercommissural width (smile width); 6. Inter-labial gap; 7. Buccal corridors; 8. Posterior corridors.

The variables measured in this study (Table 2) were chosen according to previous studies. (1)(3)(5)(16)(17

PILOT TESTS

Several studies, including those by Sarver and Ackerman,5) Hulsey,18) Krishnan et al,19 and others, used a cephalostat to position the head. The portable Siemens cephalostat used in this study was inserted in a metallic structure in order to bring it to the schools where samples were collected, and it was validated against anOrthocep OC100 cephalostat belonging to the Instrumentarium Imaging of the Universidad de Antioquia School of Dentistry. To this end,20 children were taken photograms that were subjected to paired Student’s t test, finding out that there were no statistically significant differences (0.183) between both equipment. Reproducibility of the portable cephalostat was also evaluated by intraclass correlation, which yielded values ranging from 0.911 to 0.996 for the variables under analysis.

The values of the graph ruler added to the equipment to calibrate the photos to real size (1:1) were checked with three digital calipers, finding out accuracy in measurements.

Also, to evaluate intra-operator concordance, two operators measured 20 subjects (boys and girls with different dentition types) simultaneously at two different times and with a minimum interval of two weeks in between measurements, obtaining a coefficient of intraclass correlation of 0.909 to 0.997 for the quantitative variables, and a kappa coefficient of 1 for the qualitative variables: smile arc and type of smile.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The quantitative variables were analyzed with central tendency and dispersion measures (average, standard deviation, and 95% confidence intervals), and the qualitative variables (smile arc, smile type, dentition type, and gender) with absolute and relative frequencies. All the quantitative variables were evaluated for normality with the KolmogorovSmirnov test, using P values higher than 0.05, which means that the variables had a normal distribution.

One-way ANOVA test was used to compare the quantitative variables with respect to dentition type. To compare the quantitative variables against gender, the Student’s t-test for independent sampleswas used. Comparisons among type of smile, smile arc, gender, and dentition were conducted with the Pearson x2 test, using a significance level of 0.05 for the statistical analyses. The statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS®19 statistical software (SPSS Inc.; Chicago Illinois).

RESULTS

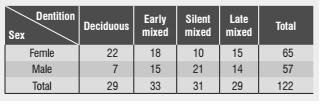

The sample included 122 children in total. Table 3 shows sample distribution by dentition type and sex.

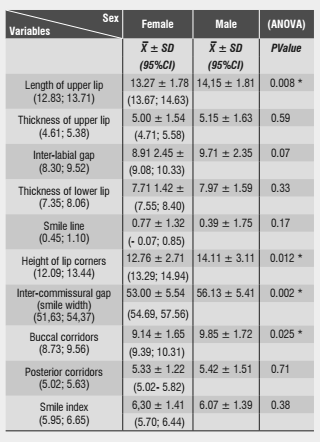

All the analyzed variables showed statistically significant differences according to dentition type, with the exception of commissural height and smile index (Table 4).

Both length and thickness of upper and lower lip at smile were similar in deciduous and early mixed dentition and between silent mixed and late mixed dentition. The table above shows that interlabial gap and inter-commissural width increased as dentition developed, just as happens with the other variables on this paragraph.

Concerning smile line, gingival exposure was predominant in deciduous dentition (0.94 ± 0.90 mm) and early mixed dentition (1.36 ± 1.41 mm). Silent mixed dentition showed a slight covering of tooth by lip and late mixed dentition showed minimal gingival exposure, being both average values close to 0. Smile line in mixed silent dentition showed significant differences compared to deciduous dentition and early mixed dentition (p = 0.000).

Oral corridors showed significant differences between deciduous and early mixed dentitions (p = 0.000) and silent and late dentitions (p = 0.000), and these corridors values increased with further development of dentition. In terms of posteriorcorridors, there were significant differences between early mixed dentition and silent dentition only (p = 0.002). Concerning smile index, there were no significant (clinical or statistical) differences among the groups.

Smile showed sexual dimorphism in four values: length of upper lip, commissural height, intercommissural width, and buccal corridors, and these values were lower in females than males (Table 5). Analyses of arc and type of smile according to dentition and gender showed that 89.34% of the kids had coinciding smile arc, 9% had flat arc smile, and 1.66% had inverted smile arc,5 corresponding to two female cases in early mixed dentition.

Sexual dimorphism was not found in the smile arc, as the coinciding arc was the most prevalent in both sexes: 89,23% of girls and 89,47% of boys.

The x2 analysis shows that dentition type is associated with smile arc (p = 0.032). No subject in late mixed dentition had flat arch, as observed in the other groups; the inverted arc only happened in early mixed dentition.

The most frequent smile type was the medium smile (54.92%), followed by the high smile (40.98%); the low smile was found in five cases (4.1%) of deciduous dentition and late mixed dentition.

The high smile predominated in deciduous dentition (58.6%) and early mixed dentition (57.8%), and the medium smile in mixed silent (77.4%) and mixed late dentition (65.5%).

According to the x2 test analysis, there was no association between sex and smile type: the most common smile type in both girls and boys was the middle smile (50.77 and 59.65% respectively). The x2 analysis showed that smile type was associated with dentition type (p = 0.001).

DISCUSSION

During smile evaluation, the methods used for image capturing must be considered. The present study sought to standardize aspects such as lighting, head position, orientation of the video camera, dynamic evaluation of tissues, and smile reproducibility. To avoid confusion variables that could arise from image capturing, as described by several authors, the methodology in this study was based on the most current protocols, validated by different authors.2)(5)(7)(17

An advantage of the videographic method is that it allows capturing the expression of soft tissues and comparing different moments during their expression, resulting in a larger amount of records and favoring the selection of the most reproducible posed unforced smile.17

As mentioned in the introduction, the present research project did not find previous studies evaluating children’s smile, only studies describing the characteristics of perioral tissues at rest. Therefore, in this discussion section we will make comparisons with smile studies in subjects older than those reported in the present study.

Smile characteristics have been evaluated in adult patients, finding out that dental and gingival exposure decreases with age. Desai et al7 studied 221 subjects aged 15 to 70 years, noting that as patients age, the exposure of upper central incisors during smile decreases; no subject older than 50 presented high smile, and none between the ages of 15 and 19 years had low smile.

The present study found medium smile in 54.92% of cases, and high smile in 40.98% of subjects, predominantly in deciduous dentition and early mixed dentition. The low smile was observed in 4% of children in deciduous dentition and late mixed dentition. Agreeing with Tjan and Miller,3) Desai et al,7 and Maulik and Nanda,12 the present study found out that the medium smile is predominant in both children and adults, but it differs with the abovementioned studies in adults since in the second level of frequency, children have high smile while adults have low smile. This could be explained by the findings by Sarver,20 Sarver and Ackerman,4) and Desai et al,7 who claim dental and gingival exposure decreases with age.

The literature is not conclusive concerning the quantitative definition of the high smile. In this study, and in accordance with the definition by Tjan and Miller,3 the high smile was described as one which shows the entire length of the maxillary incisors and the contiguous gingiva band. This classification of the high smile was later used by many authors, including Maulik and Nanda,12 Zackrisson8 and Pieter Van der Geld.21 Other authors call it prominent high smile or gummy smile when 2 mm of gingiva or more are shown.8)(10)(17

The present study observed a gingival exposure of 1.82 ± 1.25 mm in the high smile. The gingival exposure values reported by Peck and Peck16 in adolescent patients with no orthodontic treatment are very similar to those found in the present study in children. It seems that some gingiva exposure is normal during deciduous and mixed dentition. In the process of maturation and aging, a decrease in incisors exposure with age has been reported,7)(16)(22 as well as a decrease in gingival smile.5)(6)(7

It is important to note that the average gingival exposure found in this study is small (1.82 ± 1.25 mm), somewhat similar to the exposure found by McNamara et al1 (1.1 ± 2.6) in a sample of 60 patients averaging 12.5 years of age. This amount of gingival exposure would correspond to a medium smile in other publications, such as the study by Hunt et al.23 If the parameters described by these authors had been used in the present study, the vast majority of patients in this sample would have been classified as medium smile. This is a very interesting observation because it is widely accepted that the high smile is very common in children, different to the findings of the present study.

Concerning length of upper lip, Hashim et al (24 studied 27 children aged 3 to 18 years, finding out a 35% increase in males and 24% in females. Other authors7)(25)(26 also reported an increase with age, agreeing with the findings of the present study. These findings could explain the shift from high smile to medium smile, and it may suggest that length of the upper lip has a direct influence on gingival or dental exposure.

The average values found in terms of thickness of upper and lower lips, inter-labial gap, intercommissural width, and posterior corridors in smile were similar but slightly smaller than those reported by McNamara et al,1 possibly because their sample included patients aged 10 to 15 years and this study included kids aged 3 to 12 years. In a sample of 50 patients averaging 12.5 years of age, Ackerman et al (27 reported values lower than those reported in this study in terms of inter-commissural width and interlabial gap, probably because of differences between samples. Mamandras28 and Nanda et al29 reported that lip thickness increases during childhood and adolescence, reaching its maximum thickness at the end of the pubertal peak. In addition, lip thickness decreases at the end of adolescence.

Although the variables that make part of the smile index (27 (inter-commissural width / inter-labial gap ratio) showed differences, this index kept a similar proportion, with no significant differences among the dentition type groups. On the contrary, Desai et al (7 reported that the smile index significantly increases with age. In the study by McNamara et al, (1 the average smile index (6.5 ± 2.1 mm) showed a value very similar to the one found in the present study (6.2 ± 0.13 mm). Krishnan et al (19 claim that as smile index decreases, the smile reduces its youthful appearance, (19 but this is an aesthetic appreciation not related to patient’s age.

The coinciding smile arc (parallelism of internal lower lip curvature and upper incisal curvature) is determinant of the harmonic smile in adults.18)(30)(31)(32 Tjan and Miller3 reported that 84.8% of the study subjects had this condition, similar to the findings this study (89.3%). Dong et al33 and Krishnan et al19 also found out that this type of arc was more frequent among their study subjects, disagreeing with Maulik and Nanda,12 who found out that the flat smile predominated in their sample. In the present study, there were some children with flat smile in all dentition groups with the exception of the mixed late group, which could be associated with the lack of incisor eruption or with canines wear during early mixed dentition, or because of incisors wear in deciduous dentition. In the two cases of inverted arc found in this study, eruption of the upper central incisor was clearly missing.

There were differences in terms of averages of buccal and posterior corridors among the dentition groups, and these values increased with further development of dentition. This can be explained by the inter-commissural increase with age. Several authors have evaluated the aesthetic perception of buccal corridors,18)(34)(35 but values of inter-commissural width and buccal and posterior corridors were only reported in the study by McNamara et al,1 conducted in subjects averaging 12.5 years of age; their values are higher than those found in the present study, confirming that these variables increase with age.

In assessing whether there was sexual dimorphism in the studied variables, this was not found for smile type: the medium smile was prevalent among boys and girls in silent mixed and late mixed dentitions, and the high smile was dominant in deciduous dentition and early mixed dentition, with similar proportions. Statistically significant differences were only found in the silent mixed dentition group, in which females had a slightly larger gingival or tooth exposure (less than 1 mm) than males. Tjan and Miller,3 Peck et al37)(38 Vig and Brundo,36 and Maulik and Nanda12 found sexual dimorphism in terms of smile type, with a higher percentage of high smile in women, even resulting in a 2:1 ratio, suggesting that the high smile is a female characteristic, and the low smile a male characteristic.37)(38

Other variables presenting sexual dimorphism were length of upper lip, commissure height, inter-commissural width, and buccal corridors. These values were lower in females than males. This result agrees with the findings by Panossian and Block25 and Peck et al.37 Similarly, Bishara et al39 found out that the measures of facial tissues in boys aged 4 to 13 years were higher than in girls.

Although the present study suggests certain relationships to clarify the behavior of some soft tissues in smile and some of its characteristics, further studies are needed to accurately establish certain parameters of normality of smile characteristics in children.

CONCLUSIONS

Length and thickness of upper lip, thickness of lower lip, inter-commissural width, and commissural height were significantly higher in silent mixed dentition and late mixed dentition.

The high smile was predominant in children patients in deciduous dentition and early mixed dentition and the medium smile in silent mixed and late mixed dentition.

In most children under 12 years of age with normal occlusion, a coinciding smile arc can be expected.

Sexual dimorphism was not found in terms of smile type or smile arc in children aged 3 to 12 years with normal occlusion.

text in

text in