Violence as a social phenomenon has been a topic of special study; (Andreu Rodríguez et al., 2002; Buss & Perry, 1992; Buss & Warren, 2000), Buss which researchers agree in affirming that it is measured through aggressive behaviour and they emphasise the need for objective and reliable measurements in order to understand it in the subject who withstands it and thus design interventions adjusted to the ideographic characteristics that facilitate its decrease. Aggressive behaviour is understood as a type of relatively frequent and constant response over time, which can occur in various developmental contexts, characterised by particular modes of reaction of a subject towards other people, with the clear intention of causing harm either physically or verbally. Thus, aggression turns out to be one of the symptoms usually associated with conduct disorders, where the basic rights of others and the main social rules expected for the age are violated (Arango-Tobón et al., 2020; Arango-Tobón et al., 2022; Huesmann & Eron, 1984; Gómez Tabares & Narváez Marín, 2019; Olivera-La Rosa et al., 2023).

Aggressive behaviour is presented based on four dimensions or subfactors: (1) Hostility, understood as any negative judgment towards people and objects (Buss, 1961); (2) Anger, which is defined as the feeling of displeasure caused by an offense or mistreatment, generally manifested through a desire to fight the cause of it (Weisinger, 1998); (3) Physical aggression, understood as that which manifests itself through physical abuse, inflicting injury or damage to another person’s body (Solberg & Olweus, 2003); and (4) Verbal aggressiveness, which consists of hurling offensive words at others, assigning derogatory epithets, making threats, mocking and making comments or spreading rumours with the intention of making another person feel offended (López del Pino et al., 2009). The World Health Organisation (2002), in its first world report on violence and health, states that there is a higher incidence of aggressive behaviour in adolescents than in other population groups. The so-called juvenile offenders (Gómez Tabares, 2019; Olivera-La Rosa et al., 2021; Sattler & Hoge, 2008; Tapias Medina et al., 2022), manifest aggressive and criminal behaviours (Sáez Santiago & Roselló, 2001), in which they move from hostile to instrumental aggression. Hostile aggression is characterised by directly harming the person, but before this, there has been an experience of anger, while instrumental aggression is characterised by harming another person regardless of the form or means used in order to achieve what was planned, its action has not been provoked by anger, but from a state of hostility (Andreu Rodríguez et al., 2006; Buss & Perry, 1992; García-Leon et al., 2002).

Specifically, when alluding to the evaluation of the individual dimension of aggressive behaviour, it is related to the objective way of identifying it and its dynamics and according to Buss and Perry (1992) and Tintaya (2018), such evaluation, should be made taking into account that it is a constant and permanent response that aims to harm the other person, either through a physical or verbal manifestation that is usually accompanied by the emotions of anger and hostility. Aggression is usually diagnosed at the clinical level as a behavioural problem that occurs in adolescence and may be accompanied by delinquent behaviours (Sáez Santiago & Roselló, 2001). To assess this behaviour, the most frequently used instrument is the Aggression Questionnaire (AQ) of Buss and Perry (1992). This questionnaire “(...) is an instrument that evaluates different components of aggressiveness. The original version is composed of 29 items referring to aggressive behaviours and feelings and coded on a Likert-type scale” (Sierra & Gutiérrez Quintanilla, 2007, p. 105). The structure of the AQ measures the four dimensions of aggressive behaviour: (1) physical aggression, (2) verbal aggression, (3) anger and (4) hostility.

In order to make effective measurements of the presence of aggressive behaviour in adolescence and, based on the results, to design interventions adjusted to the characteristics and forms of aggressive behaviour, the AQ has been adapted in different countries and cultures, both in English and Spanish. One of the first evidences referred to in Spanish is the one reported by Andreu Rodríguez et al. (2002) in Spain, who used a sample of 1,382 students between 15 and 25 years of age and ended up confirming the validity of the structure of the four factors proposed by Buss and Perry (1992), finding a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88 in the total scale, 0.86 in physical aggression, 0.77 in anger, 0.68 in verbal aggression and 0.72 in the hostility scale, thus demonstrating the internal consistency of the instrument and therefore its reliability. Findings that coincide with those of Santisteban and Alvarado (2009), who used the original version in a sample of Spanish adolescents and preadolescents and again demonstrated that the instrument has adequate internal consistency and also a good fit to the four-factor model. The confirmatory factor analysis performed (GFI = 0.928, AGFI = 0.916, RMSEA = 0.047) in-dicated that the four-factor model fit adequately.

Likewise, López del Pino et al. (2009), based on a sample of 160 Spanish adolescents, of both genders, between 12 and 19 years of age, set out to demonstrate that the version consisting of 40 items is made up of the same four factors as the reduced version of 20.

García-Fernández et al. (2015), adapted the AQ with 993 Chilean students studying from first to fourth middle grade, in nine randomly selected centres from three municipalities in the province of Ñuble, in their versions of 29, 20 and 12 items. They found that the internal consistency indices of the four factors were acceptable, ranging between 0.67-0.78, which are in correspondence with the results obtained by Andreu Rodríguez et al. (2002). A second adaptation carried out in Latin America, was carried out by Tintaya (2018), who evaluated the psychometric properties of the Buss and Perry AQ in 1,152 adolescents from Lima-Peru, of both genders, with a schooling level of from first to fifth year of high school from educational institutions and found a high internal consistency, with an Alpha of 0.814 on content validity with a significance of p < 0.001, for all items. When analysing each item, it was determined to keep the 29 items that make up the AQ of Buss and Perry (1992), since the coefficients were greater than 0.20 in Pearson’s r.

The construct was validated using factor analysis, which resulted in four factors explaining 41.84%. A second validation study of the AQ carried out in Peru was that of Matalinares et al. (2012). They adapted the version of Andreu Rodríguez et al. (2002) with 29 items. The instrument was applied to 3,632 subjects, from 10 to 19 years of age, of both sexes, from the first to the fifth year of high school educational level, from different educational institutions in Peru. As results, it is highlighted that the reliability coefficient is high for the total scale (α = 0.836), and for the subscales: physical aggression (α = 0.683); verbal aggression (α = 0.565); anger (α = 0.552) and hostility (α = 0.650), the coefficients obtained were different from those of the adaptation. Also in Peru, Valdiviezo and Rojas (2020) carried out a new adaptation in which 600 students from three public institutions in the District of Chicama were administered the AQ, Buss and Perry (1992) version, and found content-based validity, obtaining values greater than 0.50 at the lower limit of the 95% confidence interval.

Another validation conducted in Latin America, was done in Puerto Rico, by Cruz-Peréz et al., (2013), who in order to obtain preliminary data regarding the AQ questionnaire of the 29-item version, sampled 88 adolescents between 14 and 18 years of age. Factor analyses proved to be equal to the aggressiveness scale proposed by the lead author; factor loading was greater than 0.30 and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87. When the results of the factor analysis were evaluated, it became evident that the items can be regrouped into four factors: in the first factor, seven items were grouped (α = .80); in the second, six items were grouped (α = .77); in the third, four items were grouped (α = .72); and in the last factor, four items were grouped (α = .60).

Two adaptations of the AQ have been made in Colombia. On the one hand, Castrillón et al. (2004), who used the 40-item version and found a reliability coefficient for the total scale of 0.82 and the reliability coefficient for each factor showed that for factor one the alpha was 0.81, factor two obtained an alpha of 0.86, factor three showed an alpha of 0.80 and factor four had an alpha of 0.57, demonstrating that the internal consistency of the instrument is adequate to be applied to young people. On the other hand, there is the adaptation of Chahín-Pinzón et al. (2012) who adapted the abbreviated Spanish version of 20 items. They took a sample of 535 children from Bucaramanga between 8 and 16 years of age belonging to three schools. The findings of the factor analysis show satisfactory reliability for the total scale (α = 0.82) and for the physical aggressiveness scale (α = 0.75), whereas for the other scales it varies according to age. Javela et al. (2023) evaluated the psychometric properties of the AQ questionnaire, a 19-item version validated by Castrillón et al. (2004), in a sample of 752 adolescents. The results showed acceptable goodnessof-fit indices for the second-order unifactorial model (c2 /df = 2.29; CFI = 0.977; IFI = 0.977; GFI = 0.984; AGFI = 0.979; RNI = 0.984; NFI = 0.972; RMSEA = 0.047 (90 % CI = 0.016 0.036); SRMR = 0.059) and adequate reliability (α = 0.55-0.88). It is concluded that the scale is applicable to the Colombian preadolescent and adolescent population.

When considering the two validations carried out in Colombia (Castrillón et al., 2004; Chahín-Pinzón et al., 2012) and taking into account the internal consistency of the instrument in the various investigations described, it was concluded that a new validation of the AQ for the Colombian context is required, based on the version of Andreu Rodríguez et al. (2002), considering ages between 10 and 23 years old, which in previous validations were not taken into account and which are precisely those in which young people deprived of liberty are found, which would allow evaluating how this instrument could become a valuable tool to measure and monitor aggressive behaviour, as the treatment of this population progresses, in the institutions that must provide them with protection according to Colombian legislation, and which should focus on restorative, protective and pedagogical aspects.

The use of the AQ validated in the Colombian population will provide the opportunity to make both nomothetic and ideographic adjustments in the interventions carried out with juveniles deprived of liberty, and will also allow informed decisions to be made that promote the implementation of effective treatments within the institutions, with the objective of achieving a successful resocialisation of these juveniles.

Therefore, the main objective of this research was to establish the psychometric properties of the aggression questionnaire (AQ) of the Andreu Rodríguez et al. (2002) version of 29 items, in a sample of Colombian children and adolescents between 10 and 23 years of age.

Method

Participants

The data presented were obtained from a sample of 892 adolescents between 10 and 23 years of age, belonging to educational institutions (n = 543, 60.9%) and resocialisation centres (n = 349, 39.1%), from four regions of Colombia: Antioquia 278 (31.2%), Cundinamarca 355 (39.8%), Caldas 158 (17.7%) and Valle del Cauca 101 (11.3). 617 (69.2%) were men and 275 (30.8%) were women. With respect to socioeconomic stratum, 391 (43.8%) were low (1 and 2), 476 (53.4%) were middle class (3 and 4) and 25 (2.8%) were high (5 and 6). The average age was 15 years (DE = 3.62). The voluntary participation of the adolescents was guaranteed, as evidenced by the process of obtaining informed consent. In order to establish the inclusion criteria, the age of the adolescents was considered, covering those between 10 and 23 years of age.

The institutions where the application of the instrument was carried out were distributed in different regions of Colombia. Each of these institutions was supported by a duly trained professional, who was responsible for administering the questionnaire and completing the database designed specifically for this purpose.

The sampling approach was population-based, whereby all adolescents who met the pre-established inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study. No random or stratified selection was employed.

Procedure

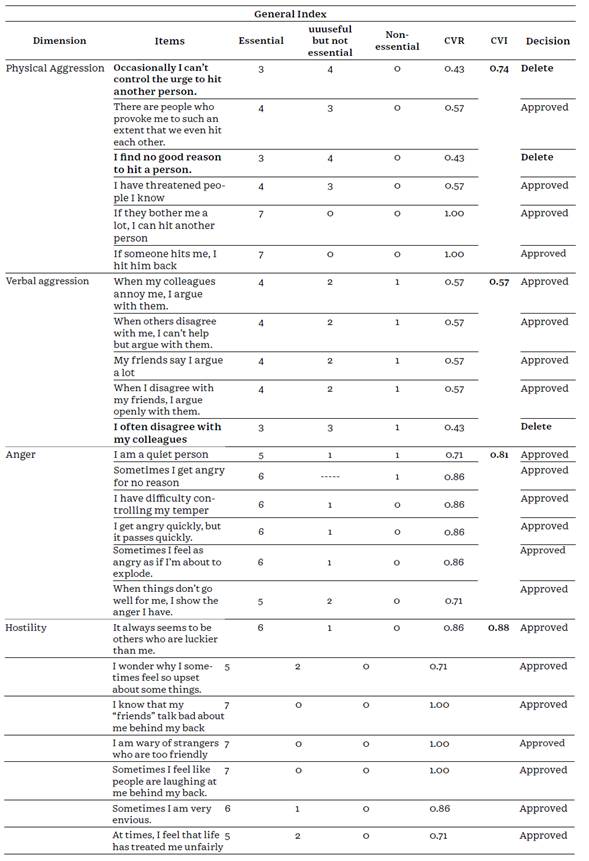

The AQ was evaluated by seven experts with the objective of adjusting the clarity of the items in accordance with the characteristics of the Colombian population. The analysis was conducted in accordance with Lawshe’s (1975) model, with modifications proposed by Tristán (2008). The experts provided a rating for each item on a scale of 1 (unnecessary), 2 (useful with adjustments), or 3 (useful without adjustments). In accordance with Tristan’s methodology, an item was deemed unsuitable for retention if its Content Validity Ratio (CVR) did not reach a minimum value of 0.58, as determined by the proportion of experts who considered it essential. However, it was observed that in the physical and verbal aggression dimensions, the majority of items would have to be eliminated for clarity. To avoid this, it was decided to adjust the items with a CVR of 0.57. Furthermore, the Content Validity Index (CVI), based on the average CVR of the approved items, had to be equal to or higher than 0.57 to demonstrate the representativeness of the subscale with respect to aggressive behaviour.

In this study, the minors gave their assent to participate, with prior consent from the Family Advocate and parents, as well as authorisation from the Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar. Participation was anonymous and adhered to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. The research has been endorsed by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Católica Luis Amigó, as stated in the minutes No. 05.

Data analysis

For the development of the descriptive and psychometric analyses, the R Studio programme version 4.0.3 (2020-10-10) and SPSS version 25 were used. For the descriptive analysis of the items, the frequency distribution was calculated to observe the tendency of responses, the average, deviation, symmetry and the discrimination coefficient, corrected correlation coefficient between the score on the item and the total obtained in each factor.

As evidence of construct validity, the internal structure was analysed through Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), using the theoretical model proposed by Buss and Perry (1992), which proposes four factors to estimate aggressive behaviour.

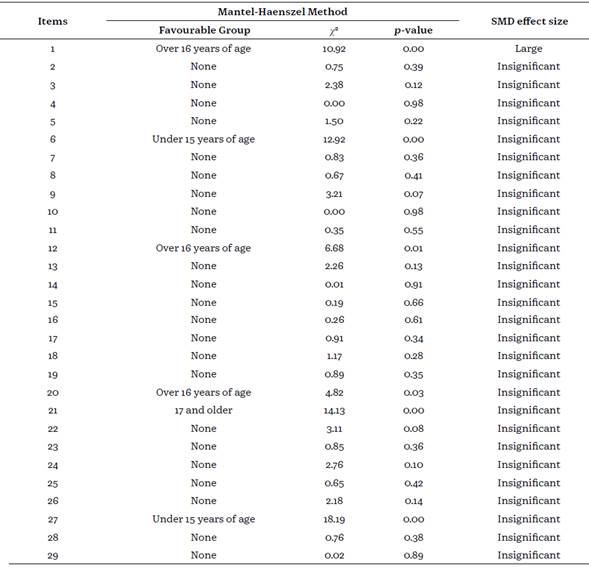

In consideration of the variability in the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants (e.g., gender, age, and institutional status), a differential item functioning analysis (DIF) was conducted prior to proceeding with the CFA. This analysis enables the identification of items exhibiting variability or bias with regard to the aforementioned sociodemographic characteristics. To this end, the Mantel and Haenszel (1959) method was employed, which is particularly effective in terms of statistical power. Furthermore, the Standardised Mean Difference (SMD) method was utilised to ascertain the magnitude of the DIF and the group to which the item may be prone to favour or disfavour.

Following this analysis, two models were tested: a factor correlation model and a second-order model consisting of a latent variable and four factors. The WLSMV (Weighted Least Squares Mean and Variance Adjusted) estimation method was used. Then, the overall goodness of fit of the model was evaluated through the χ2 (p < 0,05), a test sensitive to the sample size, and the ratio between its value and the degrees of freedom was calculated, because there is a consensus that states that values lower than 3 and with limits up to 5 is an acceptable indicator of model fit (Kline, 2015).

Other indices, such as RMSEA (Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation), estimated the overall amount of error in the model, CFI (Comparative Fit Index) and TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index). The RMSEA index quantified the divergence between the data, values < 0.06 indicated a good fit, while values up to 0.08, with 90% CI represented an acceptable fit. For the CFI and TLI, values ≥ 0.90 were considered an acceptable model fit. The correlation matrix was polychoric given the categorical (ordinal) nature of the items.

For evidence based on the relationship with other variables, the data distribution was initially analysed with the Shapiro Wilk test, which indicated a nonparametric distribution. To observe the association of the variables of both the group of participants belonging to Educational Institutions and Re-socialisation Centers, we worked with the Mann Whitney U test and to calculate the effect size we used the statistic proposed by Tomczak and Tomcak (2014), where a value equal to or greater than 0.5 was estimated to indicate a sufficiently large difference in the study dimensions and the associated groups.

Results

Table 1 shows the CVR and CVI indices according to expert judgment. For physical and verbal aggression, three items were eliminated, specifically those that obtained a CVR < 0.57, leaving a scale with 26 items.

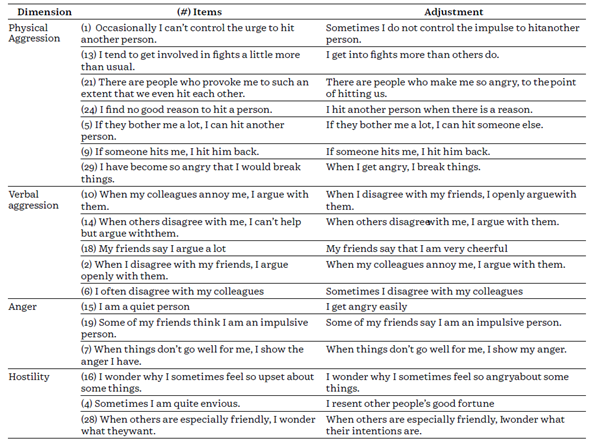

The remaining 26 items, and specifically those that obtained a CVR > 0.57, were revised and adjusted (Table 2) in writing.

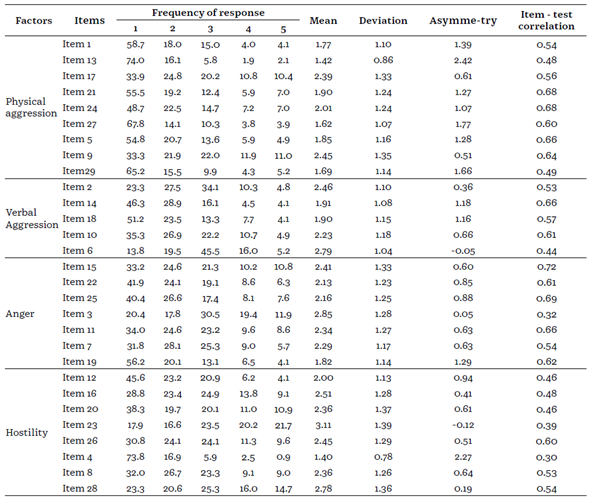

Table 3 shows that in the physical aggression factor, the responses tended to cluster in option 1, which indicates that the indicator is completely false for the participants; In most of the items, the mean response was around 2, that is, the option “quite false for me”; the deviation was observed above 1, which indicates that there was variation in the responses, with the exception of item 13 where the response preference was mostly in option 1; the asymmetry was positive, around 1, which indicates a response tendency towards the lowest values of the measurement scale, that is, 1 and 2. The item-test correlation of all the items of the factor is above 0.25, which means a tendency to homogeneity in the responses in all the items of the factor.

In relation to the verbal aggression factor, the response tendency was around 1 and 2, that is, the response preference was “completely false for me” and “Quite false for me”, with the exception of item 6 where the highest frequency was in option 3 “Neither true nor false for me”. The mean response oscillates around option 2 “Quite false for me”. The deviation of all items was above 1 indicating variation in the responses and the item test correlation was above 0.25 indicating a tendency to homogeneity in the responses to all items of the factor. For the anger factor, the response tendency was towards “Completely false for me” and “Quite false for me”. The mean response was around the option “Neither true nor false for me”. The deviation is above 1, which indicates variation in the responses, and the symmetry in most of the items was positive and close to 1, which indicates a greater preference for the lower values of the measurement scale. The item-test correlation was above 0.25, indicating that the responses of the factor items tended to be homogeneous.

Finally, regarding the hostility factor, the majority of responses were in the response options “Completely false for me”, “Quite false for me” and “Neither true nor false for me”. The mean response was concentrated in options 2 and 3 with the exception of item 4 whose responses tended toward option 1. The deviation in most of the items was above 1, which indicates variability in the responses, except for item 4 whose responses were mostly grouped in option 1. Positive symmetry indicates that the majority of responses were located in the lower measurement scale options, but are in the range of -1 and 1 standard deviation. Finally, the item test correlation was above 0.25, indicating that the responses to all items of the factor tended to be homogeneous.

Regarding the results of the Differential Item Function (DIF) analysis, taking into account gender, age and institutionalisation, a different response behaviour was observed between men and women, particularly in items 9, 17 and 21, with greater favourability in the response to men. Regarding school and institutionalised participants, a response behaviour was found in items 12 and 22, with greater favourability in the response to the group of institutionalised participants, except for item 7, which favoured participants from schools. Regarding age, only item 1 showed a different response behaviour in favour of participants older than 16 years. Finally, no DIF was observed in any of the items considering the geographical regions of the participants (Antioquia, Caldas and Valle del Cauca) (see Supplementary Materials).

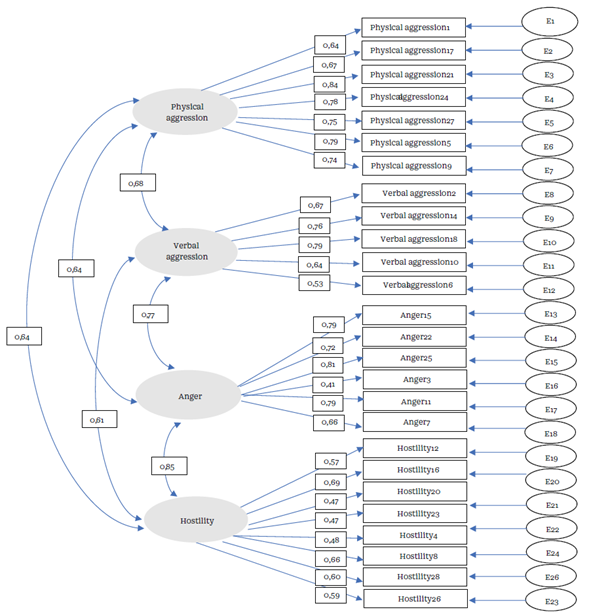

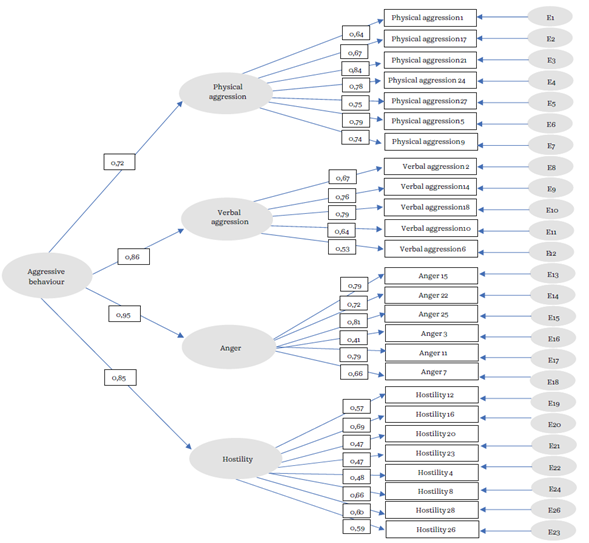

With respect to Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), two models were proposed. Model 1: Correlated factors, this model consisted of the four dimensions originally proposed by Buss and Perry (1992) and adapted by Andreu Rodríguez et al. (2002): physical aggression, verbal aggression, anger and hostility. The results of this model show a good fit (c2 /df = 3,44, CFI = 0,95, TLI = 0,95, RMSEA = 0,052, SRMR = 0,049).

Likewise, internal consistency is observed in each of the factors, in this regard the physical aggression factor obtained an omega index of ώ = 0.90, the verbal aggression factor obtained an omega index of ώ = 0.81, the anger factor obtained an index of ώ = 0.86 and hostility an omega index of ώ = 0.77. It is important to note that items: 29 and 13 of the physical aggressiveness dimension and item 19 of the anger dimension were eliminated for presenting a high residual. With respect to the correlations between factors, a correlation of 0.68 was observed between physical and verbal aggression; physical aggression and anger 0.64; physical aggression and hostility of 0.61; verbal aggression and anger 0.77; verbal aggression and hostility 0.64; anger and hostility 0.85 (Figure 1), indicating moderate relationships between the factors. The factor loadings of the items in each factor were higher than 0.4, which means that the contribution of each item to the factor was above 16%.

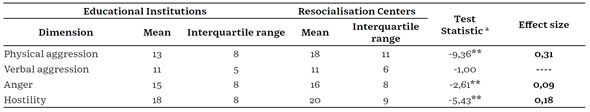

Model 2: Second-order model, in this model a general second-order factor is proposed to which four first-order factors are associated, which will be called: Aggressive behaviour. The results of this model show a good fit c2 /df = 3.48, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.053, SRMR = 0.050. With respect to the omega coefficient, the proportion of variance attributable to the general factor alone is ώ =, 0.85 and for the subscales ώ = 0.90; ώ = 0.81; ώ = 0.85; ώ = 0.79 was found; however, the hierarchical omega coefficient (ὼH) which estimates the proportion of variance attributable to the overall factor was only 0.08, lower than the hierarchical omegas for each factor which are 0. 82, 0.74, 0.85 and 0.79, indicating that there is no general factor explaining the variance of the items. In this model, items 13 and 29 were eliminated from the physical aggression dimension and item 2 from the verbal aggression dimension because they presented a high residual.

The overall factor had a relationship with physical aggression of 0.72, verbal aggression 0.86, anger 0.95, and hostility 0.87 (Figure 2), indicating moderate to very good relationships among the factors measuring the construct.

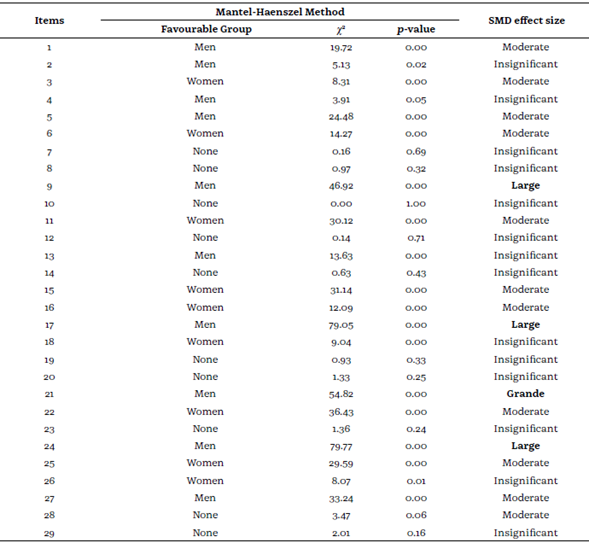

Table 4 shows that there are differences in the study variables according to the sample of Educational Institutions and the sample of Re-socialisation Centres. However, the effect size is not large enough for the results to be conclusive.

Discussion

The empirical evidence shows that the Aggression Questionnaire-AQ was validated (Content and Construct) in a sample of Colombian children and adolescents between 10 and 23 years of age. Regarding content validity, when judging the representativeness of the items that are part of each of the subscales of the Aggression Questionnaire-AQ, the expert judgment made it easier to define that those items with an overall content index of 0.57 or higher were acceptable; however, modifications were made in the wording of some of these items (Physical aggression: 21, 5, 9, 29; Verbal aggression: 2, 14, 18, 10; Anger: 15, 7 and Hostility: 16, 4, 28), adjusted to the context and suggested by the experts, therefore, in Physical Aggression, seven items of the nine of which the subscale is composed, the totality of Verbal aggression items and three of each of the Anger and Hostility subscales were adjusted.

It was found that the greatest number of adjustments to the items was made, in hierarchical order, to the totality (five) of the verbal aggressiveness subscale, since the wording of the items in the experts’ opinion was ambivalent for the attribute to be measured. The above is in contrast to what was found by Tintaya (2018), who after having submitted the content of the instrument to evaluation by 10 expert judges; found that none of the items should be revised in their scriptural structure.

On the other hand, the expert judgment yielded a CVR of 0.43 for some items, specifically in the physical aggression subscale, items 1 and 24, in verbal aggression, item 6, and in the anger subscale, item 3, scores that suggest their elimination, However, when analysing the experts’ assessment of these four items, most of them agree that they are essential and useful for assessing the respective component of aggressive behaviour, which indicates their relevance. This is also consistent with and supported by the findings of Valdiviezo and Rojas (2020), who again confirm that the items are relevant to the property they measure. However, the wording of items 1, 6 and 24 received wording proposals to adapt them to the characteristics of Colombian adolescents. In fact, the results of the subsequent factor analysis that was carried out show the relevance of these items to contribute to the evaluation of each of the factors of which they are a part, since none of these items are suggested by the models tested to be eliminated due to their high factor loadings.

However, the CVI found shows that the items in general evaluate the component in which they are located, however, the results suggest, in order of importance, a correspondence between the items and the subscales of Hostility, Anger, Physical Aggression and Verbal Aggression, a finding that coincides with that proposed by Matalinares et al. (2012), García-León et al. (2002), Buss and Perry (1992) and Andreu Rodríguez et al. (2006), who further argue that hostility is the cognitive state, and anger, is the emotional state that precedes physical and/or verbal aggression, therefore, this evidence shows that, in order to manifest physical and verbal aggression, the prior presence of hostility and anger is required.

In conclusion and according to expert judgment, each of the subscales show high content validity, which means that theoretically the items are a representative sample of what they are intended to measure (Kaplan & Saccuzzo, 2006; Kerlinger & Lee, 2002), a conclusion in which Valdiviezo and Rojas (2020) and Tintaya (2018) converge, who agree in affirming the content validity of the instrument with criteria of relevance, coherence and clarity. Similarly, and taking into account the item analysis, it was found that each item maintains an adequate discrimination index associated with the subscale to which it belongs, which indicates that there is an acceptable to good consistency, i.e., each item is associated with the factor it evaluates, which is in correspondence with the findings of Matalinares et al. (2012), who find significant item-test correlations, and is at odds with the findings of Tintaya (2018), who did not find the same with respect to two of the items (15 and 24).

The DIF results indicated gender differences, with greater favourability in males, with larger effect sizes for the items comprising physical aggression. DIF differences were smaller in the school and institutionalised groups, and the effect size of the comparative analysis was small. With respect to age and geographic area, no DIF were found to indicate relevant biases.

Regarding gender differences, these variations in the physical aggression items are related to the available evidence that males in adolescence have a greater tendency to externalising behaviours and physical aggression than females (Liu, 2004), which has been linked to social constructs around gender (Gómez-Tabares, 2019), a greater tendency to moral disengagement in males (GómezTabares et al., 2021), which may vary according to the socialisation experiences of adolescents in institutional settings (e.g., schools, foster homes, or re-education facilities) (Gómez Tabares & Durán Palacio 2020, 2021).

With respect to construct validity, the AFC across the two models tested shows that both items measure or contribute information to each of the subscales of the Aggre Gómez ssion Questionnaire-AQ (Model 2).

In the correlated factor model (Model 1), it is evident that most of the items effectively measure what is theoretically required for each subscale, thus showing factor loadings above 0.4 with a fairly satisfactory internal consistency in each factor. When comparing with several studies conducted (Castrillón et al., 2004; Chahín-Pinzón et al., 2012; Cruz-Peréz et al., 2013; Javela et al., 2023; López del Pino, et al., 2009; Tintaya, 2018), it was found that in some of them Cronbach’s alpha was estimated even working with multivariate measurement models and assuming that the factor loadings of the items in the model are equivalent and are actually different. Accordingly, Castrillón et al. (2004) and Chahín-Pinzón et al. (2012) found internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha, different from that found in the present study. That is, in relation to the Verbal Aggression subscale, Castrillón et al. (2004) (followed by Physical Aggression, Anger and Hostility in hierarchical order) note a higher consistency parameter, while in these findings, as well as in those reported by Chahín-Pinzón et al. (2012), the one that obtained the highest consistency was Physical Aggression, however, and through different parameters, the three studies converge in finding the Hostility subscale with internal consistency, but lower compared to the other factors, components or subscales.

For model 1, the correlations found between the factors were high and positive. In order of importance, a correlation was found between the subscales of anger-Hostility, Verbal Aggression-anger, Physical Aggression-Verbal Aggression and Physical Aggression-anger, which indicates that to the extent that one of them is present, the other is present, and indicates that not necessarily when someone scores high in Physical or Verbal Aggression, does he/she also score high in Hostility, which ends up explaining what was described by García-León et al. (2002), Buss and Perry (1992) and Andreu Rodriguez et al. (2002), who assume Hostility as a cognitive state that accompanies instrumental aggression, which is not mediated by the emotion that the interpretation of a situation entails; on the contrary, it can probably indicate that what precedes physically and verbally violent behaviour is anger as the emotional state of aggressive behaviour and this has probably been facilitated by Hostility, thus configuring the vicious circle of aggressive behaviour. However, this conclusion should be read with sufficient parsimony, as more empirical evidence is required to explain the vicious circle of aggressive behaviour.

Therefore, model 1 has goodness of fit, proving that there are underlying factors that correlate and explain the common variance of the items, which indicates that goodness of fit was found for the fourfactor model for the Colombian population between 10 and 23 years of age. It is clarified that items 29, 13 (physical aggression) and 19 (anger) generated a high error evidenced in the relationship with other items of the factor (subscale), so they were eliminated and the model was adjusted, leaving under this model a questionnaire of 26 items, seven in physical aggression, six in anger and in the other subscales the number was maintained according to the adaptation of Andreu Rodriguez et al. (2002). Similar findings have been found in other studies, where an acceptable goodness of fit to the four-factor model is evident (Buendia-Lozada et al., 2019; Chahín-Pinzón et al., 2012; Morales-Vives et al., 2005; Valdiviezo & Rojas, 2020).

Finally, based on the high residual degree of items 13, 29 (physical aggression) and 2 (verbal aggression), it was decided to eliminate them due to their low factor loadings and the model was adjusted. At this point it should be noted that in model 1 the items with high residuals were 13.29 (physical aggressiveness) and 19 (anger), with the same physical aggressiveness items appearing in both models with measurement error. However, Valdiviezo and Rojas (2020), Chahín-Pinzón et al. (2012), Morales-Vives et al. (2005) and Buendia-Lozada et al. (2019), did not report the elimination of items due to having a high residual level, whose argumentation basically lies in the fact that these residuals did not significantly influence Cronbach’s alpha.

Javela et al. (2023), showed that the loadings of the items on their latent constructs were statistically significant, indicating that all items adequately represented their respective construct. In this sense, the elimination of three items (29, 13 (physical aggression) and 2 (verbal aggression) did not significantly affect the content, since the relevant information is still covered by the remaining items in each dimension.

In relation to criterion-related validity, when comparing the scores obtained between the two groups that made up the sample, it was found that in the subscales of Physical Aggression, Anger and Hostility there are statistically significant differences between the two groups, without finding such differences in Verbal Aggression. However, when the significance of these differences is analysed, the TE shows that they are not relevant, which could suggest at first that the Aggression Questionnaire-AQ does not differentiate between offenders and non-offenders, nor does it predict violent acts, findings that are consistent with those reported by Buss and Warren (2000) and Sattler and Hoge (2008) who state that even though the Aggression Questionnaire-AQ was developed based on an explicit theory of aggression and represents years of research, it will be necessary to deepen the predictive validity, which involves the use of the performance of future criteria. This is a relevant issue since it will be possible to predict an adolescent offender from the scores obtained. Likewise, and due to the fact that the different findings have worked with populations of different ages, there is sufficient empirical evidence to estimate that the Aggression Questionnaire-AQ is valid to be applied starting at 9 years of age and to identify the presence of components related to aggression in clinical and healthy populations, independent of the evolutionary cycle, assuming the construct of aggressive behaviour as stable over time (Andreu Rodriguez et al., 2002).

Two models were identified, one of correlated factors and the other of second order, both showing a good fit to the theoretical model. These results are consistent with the findings of Javela et al. (2023), where an adequate fit was also observed in the analysis of the two models. After testing two models in the AFC, it was decided to opt for the second-order model, since it facilitates the satisfactory operationalisation of the theoretical model of aggressive behaviour with which the instrument was constructed, where it is assumed that the four subscales, dimensions or underlying factors such as Physical Aggression, Verbal Aggression, Anger and Hostility are necessary together, but by themselves are not sufficient to evaluate aggressive behaviour through its items (Buss & Perry, 1992).

Finally, for future studies related to the psychometric properties of the AQ, it is suggested that the sample size be increased so that it effectively represents the socioeconomic, ethnic and geographic groups of the diversity of children and adolescents in Colombia between 10 and 23 years of age. Additionally, it would be interesting to make random sample selections to ensure external validity and the ability to extrapolate the results to the general population, since the AQ is an appropriate instrument for measuring aggressive behaviour in both typical and atypical populations, and it would be valuable within the evaluative tools to have objective tests that facilitate the design of interventions tailored to the needs of subjects who present aggressive behaviour. Regardless of the two previously mentioned delimitations and in correspondence with what was stated by Sattler and Hoge (2008), it will be necessary to design predictive validity studies of the AQ in children and adolescents in order to obtain precise measures that may facilitate the identification of the evolutionary trajectory of aggressive behaviour.

According to the above, the validation of the AQ Aggression Questionnaire in the Colombian population between 10 and 23 years of age, is left with 26 items and its four subscales: (1) Physical aggression (7 items), (2) Verbal aggression (4 items), (3) Anger (7 items) and (4) Hostility (8 items) (Supplement 1). The content and construct validity is demonstrated. This undoubtedly makes it possible to have available a precise instrument adjusted to the context to assess, monitor and control aggressive behaviour in Colombian youths in conflict with the law, which will make it easier for the different actors in charge of the re-socialisation processes to identify the effects that the multimodal interventions to which these youths are subjected have or do not have on their aggressive behaviour, and thus design intervention plans adjusted to their ideographic characteristics. Having the possibility of accurately and objectively evaluating aggressive behaviour and recognising the individual characteristics that exacerbate and because it is necessary and sufficient for the interdisciplinary teams to adapt and personalise the pedagogical interventions and thus achieve an evident reduction of aggressive behaviour and reach the purpose of re-socialisation.