Introduction

Global economy is undergoing deep transformations, being Information and Communication Technology (ICT) one of the factors that have provided a real revolution in social relations around the world, especially in relation to the emergence of new applications (software) for mobile phones (smartphones). One of these applications is Uber platform (Uber, 2015), which offers people-to-people transport service with the particularity that any properly qualified driver can offer a "ride" and gain value for that service. The service has the philosophy of increasing mobility within cities. At the same time, it provides an "extra" compensation for drivers who often come and go with their empty cars. Moreover, sharing services, as in this case, increases mobility and better harness natural resources (G1, 2015; Olhar Digital, 2015). However, this application encountered resistance from a social actor called "taxi drivers", who proclaim that Brazilian law restricts this activity within the category (CONTRAN, 2004), bringing the issue to the spotlight of government entities (G1, 2015).

It is observed that the border of the discussions is in "hitchhiking" without remuneration. Theoretically, a ride is not charged, and the argument is that if a figure is charged in consideration of services then it should follow local law; being Law 12.587/2012 in the case of Brazil (Governo fed eral do Brasil, 2012). Faced with such situation, taxi drivers will need to develop new skills to co-exist with technological innovations. One of those is entrepreneurial skills within the professional activity.

In this scenario, the authors present the following research question: What is the level of entrepreneurial skills of Bra zilian taxi drivers? It is observed that such a traditional activity, regulated in several countries, is faced with a chal lenge of reinventing itself or running the risk of becoming history. With that in mind, the aim of this study is to provide an assessment of the degree of entrepreneurship of taxi drivers so that these social actors can continue to secure their place in society. The object of the research is the perception taxi drivers have about their entrepreneurship characteristics. In this dynamic, the study does not intend to be "essentialist" like those of Christensen and Carlile (2009); Flores, Gomes, and Santana (2014); Gartner (1988); or Shane and Venkataraman (2000). Therefore, the researchers of this study believe that participating subjects used their past and present life trajectory to answer the questions. Thus, by studying taxi drivers organized in the form of a cooperative, linked to a methodology already known in the academic environment -such as the Gen eral Enterprising Tendency model (GET) by Caird (1991)- it broadens the knowledge about the entrepreneurial features of taxi drivers.

This research is justified by the limited number of studies on this important actor in society, that is, taxi drivers. In this way, the study can serve for suggesting public policies aimed at enriching the entrepreneurial activity of these actors. The results of this exercise could become propellers of training programs of various organizations to support entrepreneurs. Taxi drivers are important actors when it comes to solidarity economy in a society that gives more attention to environmental management and social responsibility issues. The article is divided into five sections: introduction, literature review, research methodology, discussion of results, and final considerations.

Theoretical reference

The research proposal reveals three important points for this study: taxi drivers, entrepreneurship, and the method for evaluating entrepreneurship.

Working Conditions of Taxi Drivers: Characteristics

The service called "taxi" refers "to the individual passenger transport, with rental vehicle provided with taximeter" (Portaria 292, 2008). In this mode of transport, the passenger allocates the car and the driver to a certain route. Nobrega (2008) records that to be a taxi driver it is necessary to have a government authorization for the exercise, known as a "license" (Dias, 2007), which is granted by the municipal government (Lei 12.587 de 2012). To be a taxi driver, the interested party must undergo a training program dictated by the National Traffic Council (CONTRAN) that includes 28 hours of classes (Resolucáo 168, 2004).

Di-Muro-Perez (2001) emphasizes the social importance of taxi drivers, since they offer transportation with safety and comfort to the users/passengers. In this scenario, it is required of the professional taxi driver, besides to safety and comfort, to show ethical attitude and special care with personal marketing, considering that the ability to serve is highlighted by Castelli (2006) as an important attribute in the performance of the activity. The ability to express themselves well in their language, as well as in other languages, besides the monitoring of technological evolution, are also important attributes to this social actor.

The monthly remuneration for taxi services by holders is around brl 5,000.00 (USD 1,327.422). The taxi drivers who do not have the "license" can "rent" (around BRL 200.00 or USD 53.07) the cars of the taxi drivers who hold the license. In this case, they are called "assistant taxi drivers".

Nobrega (2008) points out that generally taxi drivers hold higher education than the secondary level. Many of them have a college degree. This author also mentions that taxi drivers enter the profession after losing their original jobs; that is, the occupation of a taxi driver is a secondary and not a primary option of occupation. The author reveals in his research that the majority of respondents have become professional taxi drivers because of the process of downsizing in organizations.

Moreover, Veloso, Oliveira-Filho, and Medeiros (2009) seek to describe the identity perceived by these professionals. The results of the survey carried out by these researchers show that taxi drivers are disillusioned with the profession as they conceive it as decadent but necessary to ensure their survival. The interviewees portray themselves and the group to which they belong as workers struggling to survive, thus legitimizing the need to choose alternative transportation. This survey also highlights that most respondents report that before they entered the profession of taxi drivers their financial situation was more stable. In addition, Rosa (2012) reinforces the image of "survival" by taxi drivers when he states: "[...] even with the fear of crime and the factors that aggravate their health problems, the best remuneration becomes practically the only justification for such preference (as a taxi driver)" (p. 542).

The work of the taxi driver is carried out in the open public environment, so these professionals do not have a restricted and defined place to carry out their tasks. They work out-side the walls of the organizations, being subject to conditions such as bad weather, traffic jams, and the route of urban roads (Battiston, Cruz, & Hoffman, 2006). In the violence aspect, Silva-Neto (2011) and Nascimento (2010) studied mechanisms (signs, gestures, and looks) used by taxi drivers as mitigation to vulnerability in their working day. Gany, Gill, Ahmed, Acharya, and Leng (2012) point out that six out of ten taxi drivers in large cities report increased working hours of or equal to twelve hours daily. This fact increases the risk of high blood pressure (Vieira, 2009). Barros et al. (2013) and Lopes and Simony (2013) observed a high level of alcohol consumption, smoking, high risk of obesity, consumption of energy drinks, and high risk of developing diseases such as disc herniation, what was also observed by Chanffin and Andersson (2001). However, the stress factor is institutionalized among professionals, according to Braga and Zille (2015).

Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship has attracted significant interest from many researchers. Several areas of entrepreneurship knowledge have been studied, such as psychology, economics and business administration (Carlsson et al., 2013; García-Cabrera & García-Soto, 2008). Serafim and Feuerschutte (2015) note that discussions on entrepreneurship arose from the early works of Richard Cantillon and Jean-Baptiste Say (Carrasco & Castaño, 2008). These authors report Schumpeter's ideas (1883-1950) on entrepreneurship as "an agent that, by promoting new combinations of factors of production, promotes economic development" (p. 168), and compare the desire of the entrepreneur to the desire to set up a "private realm", "will to win", the satisfaction of creating, and developing and implementing innovations (Kreiser, Marino, Dickson, & Weaver, 2010; Lim, Morse, Mitchell, & Seawright 2010). In fact, we are talking about entrepreneurship through business opportunity (Acs & Amorós, 2008; Valliere & Peterson, 2009).

Since then, the economic scenario of the first studies on entrepreneurship has changed. One of the elements of this transformation is the unemployment rate. This aspect is motivated by the recent economic crises and the technological advancements that increase production combined with the need for fewer people (Esther, 2014).

Additionally, Nassif, Ghobril, and Amaral (2009) recorded the perceptions of unemployed individuals who became entrepreneurs, highlighting the following: (i) the feeling of lack of perspective; (ii) feeling of rejection by certain social groups; (iii) deep sense of lack of opportunities; (iv) helplessness; (v) feeling of helplessness when facing situations previously experienced; and (vi) feeling of living a difficult time. This perspective leads to the only option of undertaking not to fail even more. In this context, according to Nobre (2012), public policies encourage entrepreneurship as the preferred way of survival in Brazil, and Europe as well. Thus, entrepreneurship is a means of regaining the right to work (Almeida, Santos, Ferreira, & Albuquerque, 2013).

Cunha (2007) characterized this public policy alternative as a "Salvationist" and "self-bosses" awareness strategy, as well as a mechanism of persuasion among unemployed. In his dissertation, he reports that the interviewees presented a "missing about employment and fixed salary" (p. 144). This fact reinforces the thesis of entrepreneurship by necessity as an alternative of survival.

On their behalf, Barros and Pereira (208) studied the en trepreneurship rate, expressed by the opening of new companies and their impact on the gross domestic profit (GDP), and concluded that entrepreneurship was associated with the reduction of unemployment, but not with economic growth. The Global Entrepreneurship Research Association (GEM, 2014) points out that the proportion of entre-preneurs by opportunity in relation to the Entrepreneurial Start Rate (TEI) in Brazil was 70.6%. This means that each entrepreneur by necessity has 2.4 person per opportunity. The gender of Brazilian entrepreneurs still continues to lead with males at 51.7% (GEM, 2014) followed by women at 48.2%. This situation is not dominant if you observe the ratio of the percentage that started a business and another group that has already stabilized.

The level of schooling among entrepreneurs stands out from those of level 2, including the incomplete first grade or the incomplete second degree (GEM, 2014). In this scenario, it is the band that launches the most in the market and the band that keeps up with the ventures. Therefore, it is possible that people without access to the higher level will find it difficult to be replaced in the market and, by necessity, launch themselves into the entrepreneurship of their business.

Theoretically, level four (and onwards) has more years of study; however, does not represent a significant highlight among entrepreneurs. Thus, even if the entrepreneurs of this level leave their formations, they do not seek to start their own business. When we talk about the income range, entrepreneurs return mostly up to three minimum wages (GEM, 2014). Considering the minimum wage at BRL 724.00 (USD 271.97), there is a monthly income of BRL 2,172.00 (USD 815.92). These values reinforce the position of Brazil under the GEM (2014) of being driven by efficiency and the pursuit of innovation, whose next step is towards market innovation. The civil status dimension is highlighted by the GEM with predominantly married being the majority of 47.8% followed by unmarried at 27.7%.

General Entrepreneurial Tendency (GET)

The initial focus of studies on entrepreneurship was the subject entrepreneur (behaviorist approach). This type of approach focuses attention on the person entrepreneur. The studies aim to observe, describe, and propose a measurement of the characteristics of the subject related to entrepreneurship. From this premise, the authors of this research understand that the thematic centered on the entrepreneur subject is the beginning of the studies of en trepreneurship. To understand the perceptions of this subject is to understand how he conceives his environment.

In this study, the authors understand that the Caird model (1991) is adequate. This model is called General Entre preneurial Tendency (GET), and has been present in the academy, namely: general occupations (Souza, Silveira, Nascimento, & Santo, 2014); among students of the busi ness student course (Dal-Molin-Flores & Santos, 2014; Gaiáo et al., 2009; Iizuka & Moraes, 2014; Pantzier, 1999; Simões, 2012); professional managers (Guerbali, Oliveira, & Silveira, 2013; Russo & Sbragia, 2007); lectures (loyal, 2011); students of several courses (Rosa, Rosa, Berto, & Duarte, 2011; Vedoin & Garcia, 2010); accounting students (Carreiro, Countiho, & Coutinho, 2010; Niveiros, Almeida, & Arenhardt, 2008); and engineering students (Araujo & Dantas, 2009; Lira, Lira, & Morais, 2005; Peloggia, 2001).

This GET model measures entrepreneurship in five categories: (i) need for achievement; (ii) need for autonomy; (iii) creative tendency; (iv) calculated risk-taking; (v) locus of control (impulse and determination). The need for achieve ment is highlighted by Russo and Sbragia (2007) as vision of where you want to go, self-sufficient, in most cases a more positive attitude, self-confidence, persistence in goals, high level of energy to achieve your goals, and complete the vision you want. Simões (2012) points out that the shortcomings of this dimension suggest a lack of ambition and disbelief about the possibility of success. Thus, preference for stability, order fulfillment, and pre-established tasks are neglected by these below-average indices.

The need for autonomy is related to personal fulfillment through unconventional activities, most often working alone. Accordingly, the entrepreneur can prioritize his per sonal goals (focusing on the vision) and express and make decisions instead of receiving orders, being reflexive to external pressures (Russo & Sbragia, 2007).

The creative tendency, according to Dolabela (2006), is one of the main characteristics of the entrepreneur. Creativity can be born or developed. It is through creativity that one perceives the market opportunities that other social actors do not perceive (Degen, 2005). This ability is also related to imagination, innovation, tendency to daydream, versatility, curiosity, generation of ideas (through observation), intuition, aptitude for new challenges, novelty, change of new technological, means of contact with the client, and seeking a greater approximation and availability. In addition, Dolabela (2006) points out that this dimension presents weaknesses in the Brazilian profile, with shortcomings mainly related to innovation and technology transfer. This shows that Brazilian entrepreneurs cannot create new markets, but prefer to copy existing businesses rather than presenting new businesses (Simões, 2012, p. 105).

As for the calculated risk-taking, this is related to the ability to act with incomplete information, assess the likely benefits against the likely failure to accurately value their own skills, and set goals that can be met. In this scenario, assuming the risks of Dolabela's decisions is a great feature of the entrepreneur (Salim, Mariano, & Nasajon, 2004).

On the other hand, the locus of control (impulse and deter mination) is related to the ability to act on market opportuni ties and take action to be asked or forced by events (Uriarte, 1999). Caird (1991) highlights the ability to suddenly shift to another alternative strategy to face the situation or overcome the obstacle. The inherent characteristics of this category are: seizing the opportunities, not believing in destiny, making their own luck, confidence in themselves, and equaling results with efforts (Ferreira, 2008).

Research Methodology

This study is classified as theoreticalempirical. According to Demo (1985), this type of research aims to extract part of a reality (new technological challenges of taxi drivers) and seeks a theoretical framework capable of explaining the point studied. In this scenario, the research is also ap plied to this reality. In the bibliographic review phase no study was found with this same purpose; therefore, this attempt of systematization is classified as exploratory. As a procedure, it is classified as quantitative, using a mea-surement instrument that involves statistical treatment of the data. The research is also interdisciplinary involving other fields of knowledge, such as administration, social psychology, anthropology, and sociology. Data sources are primary and were collected only once (Cooper & Schindler, 2003) with the subjects (taxi drivers) in the first half of 2014. The direct relationship between the research and the researchers is of the type non-participant.

The research population is the professional taxi driver cooperation. The sample is non-probabilistic, following the convenience sampling. In this case, the largest taxi cooperative was chosen in the city of Santo André, state of Sáo Paulo, Brazil. The drivers were then invited to participate. The total number of associates is 230. Considering a desired 95% confidence level, a maximum error rate of 0.05 with a 0.5 standard deviation of the population, a sample of 145 taxi drivers was reached. No form was dismissed for lack of completion.

The data collection plan involved the invitation to the management of the cooperative and then an invitation to the cooperative. Questions were provided to those who accepted. Five meetings were held with taxi drivers, given the schedule. The instrument used for data collection followed the model proposed by Caird (1991) called Gen eral Enterprising Tendency (GET), which was developed in Unit Business Training and Industrial Durham University Business School (current holder of the copyright). The Portuguese version was made and tested by Simáo (2012). This instrument had 54 statements added to socio-demographic data. The instrument options followed the Likert 7 degree scale for each participant.

The data analysis plan was designed following the methodology of Caird (1991). The evaluation of the answers was grouped in a database and the questions related to the five dimensions in the GET test, as shown in table 1.

Results

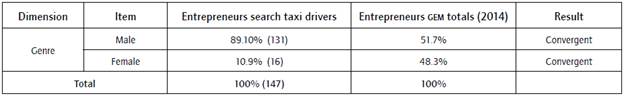

The gender in the survey indicates that of the 147 inter-viewed only 16 are women (11.03%). This data describes the population as highly masculine. GEM indicates convergence of the data. Comparing this information, it can be seen that, in general, women are well away from men in the transport segment. Table 2 presents the results.

The marital status of this population indicates that the majority (59%) is married or in a state of stable union. Table 3 presents the results.

Research data converge between married, stable union, and single people. This percentage of married couples denotes a greater responsibility of the businessman and businesswomen to economically maintain his family. The position of the widowed and divorced is divergent. In this scenario, a greater number of widowers were observed in relation to the divorced. This activity is likely to provide greater flexibility and socialization of these widowers.

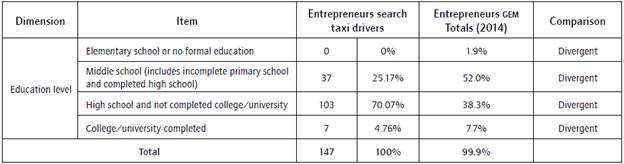

Regarding academic training, the complete high school stands out among taxi drivers at 43.45%. Second in frequency is the middle school, at 15.17%. It is observed that the level college/university is next to the taxi drivers with high school. In both situations, the numbers are small relative to the full-time high school (43.45%), which may mean that taxi drivers do not continue their studies at a college/ university, preferring work instead of studies.

Analyzing the records of Nobrega (2008), we observe a re cord of taxi drivers attending the high school. Looking at the survey data, it can be inferred that a large part did not continue their studies at the higher level. According, to taxi drivers' opinion, it can be inferred that the training course (Resolucáo 168, 2004) and the "license" of operation (Dias, 2007) are sufficient for the exercise of the profession. The paralysis of studies in a society increasingly dependent on innovations can lead to the marginalization of this activity, since new technologies impose diary challenges (table 4). In addition, table 5 presents a comparison of the research findings with the GEM (2014) results.

Table 4 Level of schooling among taxi entrepreneurs identified in the survey.

Source: own elaboration.

Each driver was asked how long he/she had been working in the Cooperative Taxi Drivers Organization. The approximate mean was 7 years with a 0.538 deviation. The minimum time in the Cooperative was one year (4 occurrences) and the maximum period 35 years (1 occurrence). The survey data showed that taxi drivers have, for the most part, already completed "collegiate". Another scenario is observed in the general profile of the GEM (2014), as presented in table 4, showing that new career entrants understand that school is necessary.

In addition, subjects were asked their current level of satisfaction with the cooperative: whether they are satisfied or not. Answers are presented in table 6.

The percentage of satisfied enterprising taxi drivers is 93.20%. This demonstrates they are happy with the per formance of their activities and will likely continue in the industry. The low level of people dissatisfied shows that they are developing the activity to maintain their economic situation. Comparing our results with those of Veloso, Oliveira Filho, and Medeiros, data proves to be divergent. Both these authors and Rosa (2012) speak of a "survival" activity, although this fact was not evidenced in our study.

Thus, it can be inferred that subjects have already institutionalized the present situation and understand it to be sufficient.

It was also asked if these entrepreneurs had other economic activity parallel to that of a taxi driver. Results are shown in table 7.

It is observed that, even with a stressful job (Silva-Neto, 2011; Nascimento, 2010), entrepreneurs complement their income with other activities, which in most cases are analogous to those of passenger transportation. Besides, subjects were also asked about the hours they worked. Data to this question is shown in table 8.

Results show that taxi drivers mostly limit work to 8 hours, as well as any other organization on the clt Consolidation of Labor Laws (Lei 5452/1943). However, the percentage that works 12 hours occupies the second place with a small margin from the first place. This information confirms the postulates by Gany et al. (2012). Thus, this expressive part of the population is more willing to do work-related pathologies, as highlighted by Vieira (2009) and Chanffin and Andersson (2001). High hourly rates are not perceived as harmful, according to Braga and Zille (2015). It is also expressive of the number of professionals who work less than 8 hours and do not have a second job. In this context, respondents were asked if they ever think about giving up their place as entrepreneurs; results are shown in table 9.

It is observed that the possibility of "rarely" is very close to the frequent option of "sometimes". This way you can verify there is no majority. It is inferred that working conditions associated with the risk of violence may reinforce the thesis of the "sometimes" option.

The result of the averages of all dimensions is presented in table 10. It can be observed that in none of the dimensions of the test did the taxi drivers reach the average to be classified as entrepreneurs. Results show that the average that came closest to the objectives was that of autonomy. The furthest was the need for achievement.

Regarding the "need for achievement", the index was 39.25 points, lying below the average, which is 54 points. Only 7 (4.82%) taxi drivers were equal to or above the average. Finally, the standard deviation was 9.05. This means that much of the characteristics related to this category were identified between taxi drivers. Technically, the service has little variability, which may explain these indices being below average. This dimension was the one that moved away from the average considered by the study, 14.75. Another point that may be related to the working conditions experienced by taxi drivers is the high-stress index, as reported by Braga and Zille (2015).

The Simões placements (2012) characterized as lack of ambition and disbelief regarding the possibility of achieving success. This may be linked to the research by Veloso, Oliveira Filho, and Medeiros (2009), who identified a professional disillusionment image caused by a de cline of image; albeit necessary to their livelihood. Still, according to Simões suggestions (2012), the following issues stand out: a preference for stability, following orders, and carrying out pre-established tasks. As for "need for autonomy", the obtained index was 18.59, being below av erage in 5.41; the shortest distance between the result and the expected average, which was 24 points. In addition, the standard deviation was 4.68, the lowest level in the survey in relation to other dimensions.

In a more detailed analysis, the survey demonstrates that only 16 subjects reached average or above. Considering the population, only 11.03% reached the entrepreneurial average. This construct is related by Russo and Sbragia (2007) personal fulfillment through unconventional activities and, most often, doing a job alone. This statement is in strong adherence to the results found. Thus, the drivers working alone prioritize their goals and make decisions instead of receiving orders. Supporting this claim, Simões (2012) points out that low rates of this item refer to a pref-erence to work for others rather than themselves.

Another aspect shown in the construct is sensitivity to external pressures. In this case, it appears that would be the pressures of their peers. However, passenger transport activity involves the driver and his passengers, a power relationship in which the taxi driver "accepts" customer decisions.

The overall score produced by the construct of "creative tendency" was 38.86, being below the indicated average, which was 48 points; unlike the data where the average was 9.14. Only 18 taxi drivers (12.41°%) were average or above it, with a standard deviation of 7.19. For Dolabella (2006), creativity is one of the main characteristics of the entrepreneur. In the case of this research, that was not highlighted. The creative ability can be developed through courses and training as well as the proper course of a taxi driver. Furthermore, the creative capacity allows the taxi driver to identify opportunities often hidden in social relations (Degen, 2005). Deficiencies in this ability may represent economic loss and, in some cases, deletion from the market. Therefore, this low score (creative tendency) can be the reason behind several aggressive acts against Uber professional drivers (Higa, 2014). As an example, a peculiar fact was reported by London taxi drivers: they co-exist peacefully with Uber drivers.

Russo and Sbragia (2007) point out that this ability is also related to the exercise of the imagination. It is in this regard that the entrepreneur is seeking a new opportunities through innovation. In the case of taxi service, this index shows little development of this ability, since the entrepre neur driver can also act as an advisor to its clients, not only in the return schedule but can volunteer to do other ser vices involving assets.

Creative ability is linked to the development of ideas that can become business opportunities. These ideas can come in the form of challenges that have been overcome to achieve the desired dream. Thus, the idea of Dolabela (2006), when he speaks of deficiency in this dimension, held true. Accordingly, taxi drivers prefer to do the same service and just think of innovation as a competitive advantage in the market.

Regarding the "willingness to risk", the index was 37.26 points, lying below the average, which is 48 points; unlike the results with the average of 10.74. Finally, the standard deviation was 7.00. Willingness to risk is an important feature of the entrepreneur (Salim et al., 2004): The taxi drive diary work with incomplete, inaccurate information. This it's parts of the process to undertake. However, it was not perceived by this survey among taxi drivers. Based on the results, it can be inferred that taxi drivers prefer a safer service than an activity that imposes risk situations. When subjects reach this average it is inferred that they have the ability to make decisions in uncertain conditions, without having all the information that induce them to do so.

Regarding the "locus of control (determination)", the index was 39.67 points, lying below the average, which is 48 points. The difference in data reaches 8.33, the standard deviation was 8.69. This construct relates the ability to act on an opportunity and make the decision about undertaking it. In this case, the results were below average. This determines difficulty in suddenly changing the strategy to overcome an obstacle (Caird, 1991). Based on this, Simões (2012) suggests that low levels in this dimension put luck as responsible for the success at the expense of self-effort to achieve.

Determination can be expressed in opportunity identifica ron but can be lost for lack of initiative. It can be inferred that, although passengers want to reach the place, drivers did not even try to identify other services that could be performed; for example, taking clothes to the laundry room of his client, or even seeking some object elsewhere in the city. These numbers may denote a lack of confidence in oneself (Ferreira, 2008).

Final Considerations

It is known that economy is changing. Many are the innovations in both services and products that firms or independent inventors have been creating. Likewise, society is changing by generating new dynamics and relationships between both people and organizations. Thus, the main goal of the present study was to provide an assessment of the degree of entrepreneurship of the taxi drivers subject of our study. In other words, to present a trend of taxi drivers' entrepreneurship as a response to the changes taking place in society.

The survey results indicate that none of the five constructs proposed by Caird (1991) on entrepreneurship have been hit by the population. The construct that is more distanced was the need for achievement. Besides, persistence of attitudes, optimism, confidence in oneself, and looking for a goal prove to be far from the entrepreneurial profile.

The impulse construct and determination are reinforced by this construct. In this construct, impulse also proved to be below average. Finally, the creative tendency construct was below average. Taking into account this information, the authors draw attention to this result, since this trend is important in all aspects of the labor market. Deficits in these activities can lead to stressful conflicts and justice may be the only alternative to conflict. Additionally, fostering the creative trend can help taxi drivers find a peaceful solution to new forms of competition on the passenger transportation market.

The data shows that taxi drivers are entrepreneurs by necessity and not by chance. "Necessity entrepreneurs" are individuals who start small enterprises out of necessity. This feature can be reinforced by the fact that most of them are married and need money to keep their homes; coupled with this, the characteristics of other constructs reinforce the thesis of entrepreneurship by necessity and not by chance. These facts mean that taxi drivers need to increase their entrepreneurial skills in order to be coop-erative members as they are responsible for the success or failure of the organization. The research did not focus on assessing whether these cabbies are "dressed" for the cooperative drivers or not. However, without an entrepreneurial profile, which requires a cooperative, it runs the risk of being manipulated by other interests.

The findings are that all the indicators seem to have low drive (latently) to the difficulties of identity. This conclu sion is indicated by Veloso, Oliveira Filho, and Medeiros (2009). The below average numbers suggest a lack of determination, creativity, autonomy and calculated risktaking (constructs analyzed) for the taxi service. Such records suggest that the taxi driver did not want nor prepare for this work, confirming the idea of Nobrega (2008) of this as an "alternative employment" for "survival". Connecting this reasoning to the educational level, the environmental institutionalization of the phenomenon is evident. It is as if the thought of the taxi driver was: "One day I'll take the taxi".

Expanding the training of taxi drivers could reverse this to an active subject modifying/changing their environment independently. What stands out from this information is that the passenger transportation market is undergoing a deep transformation: the creation of another social actor that competes with the taxi drivers. Strategic manage ment techniques can be very useful within this new market reality, since they will boost capabilities, as Caird (1991) details. However, it is unlikely that a competitor will dis-appear from the market. Judicial decisions may contain them temporarily. However, the service could be done in a "hidden" way.

The fact is that the new information and communication technology requires that challenges faced by society must be overcome so as to achieve a new order. Training programs for taxi drivers to increase their insight into business are necessary. It is understood that old challenges now have a new dynamic: technology is increasing competition.

This work has some limitations we would like to refer to. The first is the sample size, since participants do not represent the totality of cooperative taxi drivers of the city studied, much less a generalization to other city unions. Furthermore, the authors believe that greater indepth studies need to be carried out, and that research on the entrepreneurial characteristics deserves an extension of the field of study.

Up to now, little is known about the effects of new technol ogies on mobility and entrepreneurship within this context, or how peer-to-peer technologies and the overall development and spread of Internet are generating impacts on taxi drivers. This manuscript provides broad information on the degree of entrepreneurship by these taxi drivers and, because of that, results help to achieve a more com plete picture of this phenomenon.

A study to evaluate the "cooperativism spirit" among taxi drivers is suggested, evaluating their personal values with the cooperative. An extension of the study with other taxi drivers is also suggested. Finally, it is suggested that support agencies maintain periodic evaluation tools on their members, thus aiming at a constant vigilance and development process that becomes necessary for facing the new challenges imposed by society.