Introduction

During the last few decades, care and concern for the environment have turned into one of the main priorities for sustainable development at a global scale. This is reflected in the growing number of international policies oriented towards the protection of the environment -with the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations (UN) as a prime example (UN, 2015)- and an increasing public interest in adopting a lifestyle that generates the lowest possible environmental impact (Vita et al., 2019). In this context, much of the environmental impact of the population is associated with consumption behaviors and the processes used for the elaboration of consumed products. In other words, most of the environmental impact is not caused directly by household activities, but generated during the production of consumption goods. For example, in a recent study Yin et al. (2020) observed that the consumption of goods such as food, clothes and services represents around 64% of the household carbon footprint in Beijing. Similarly, Vanham, Gawlik and Bidoglio (2019) found that in Hong Kong households, the indirect use of water associated with the consumption of food is around 15 times higher than direct water consumption. This trend has been observed in practically all the regions of the world, with environmental footprints related to consumption accounting for more than 84% of total environmental impacts of the population (Tukker et al., 2016). In the case of Latin America, this situation is also characterized by a significant inequality between countries, as happens within the socioeconomic sectors of these nations (Zhong et al., 2020).

Moreover, at an operational level, a more sustainable pattern of consumption can be achieved by encouraging the purchase and utilization of green or ecological products. Even though there are diverse definitions of what is understood by “green products”, a simple yet clear definition is provided by Sdrolia and Zarotiadis (2018), who, based on an extensive review and acknowledging the fact that no product is free of environmental burdens, define a green product as any product (tangible and intangible) that minimizes its environmental impact (direct or indirect) during its entire life cycle and is subject to current scientific and technological status. Considering that both production and contextual elements regarding consuming decisions can have a significant effect on the environment, understanding the sociocultural and psychosocial factors of a green product purchase decision process becomes of great importance for the development of multiscale sustainable strategies (Singh & Gupta, 2013). In this line, behavioral scientific studies are fundamental to develop strategies to inform consumers about the environmental consequences of their consumption decisions, guiding them on the basis of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and other environmental analysis tools towards more sustainable attitudes, practices, and behaviors (Polizzi et al., 2016; Steg & Vlek, 2009).

Considering the above, even though pro-environmental behaviors such as green product consumption has been studied in Euro-American and Asian countries (Alzubaidi et al., 2020; Gatersleben et al., 2014; Paul et al., 2016), to the best of our knowledge there is a lack of studies focusing in Latin American consumers, specifically the Chilean population.

Chile is characterized by having one of the highest environmental impacts per capita in Latin America, with an estimated carbon footprint of 6.24 tons of CO2 equivalent per year per person in 2018, compared with an average of 4.95 tons of CO2 equivalent per year per person in the Latin American and Caribbean region (The World Bank, 2020). Regarding environmental concern, according to data from a recent international study (Électricité de France [EDF], 2019), 80% of the respondents perceive a bad environmental situation (above the world average, which is 54%). Likewise, 65% of the Chileans are “much more concerned” about this issue than they were five years ago, a figure that reaches a world average of 37% (EDF, 2019). However, this perception of the relevance of environmental issues has not been translated to an operational characterization of the psychosocial factors that influence the adoption of sustainable practices, such as attitudes and intentions of ecological behaviors (Gifford, 2014). This is an important step for the successful implementation of environmental policies that require societal-wide adoption.

In line with these antecedents, the last reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2018; 2019) highlight the relevance of directing the research efforts to better comprehend and potentially modify the behavior intentions towards more sustainable lifestyles. According to Ajzen (2002), if people evaluate the objective behavior as positive (attitude), there will be a higher intention (motivation) for the actual performance of the behavior. This main idea drives the development of different theoretical-conceptual models that can be used to understand the consumer’s purchase behavior of green products (Albayrak et al., 2013).

Theory of reasoned action [TRA] (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). The TRA model is utilized to assess non-rutinary decisions, using psychological/cognitive processes to comprehend the contextual decision making of consumers (Han & Kim, 2010). Its central principle is behavioral intention (BI), understood as the disposition towards the performance of the behavior in question (Ajzen, 1985). According to this model, the purchase intention of green products would indicate up to what point consumers would be disposed/prepared to buy green products or to adopt more sustainable options/choices (Paul et al., 2016). In operational terms, BI is determined by both a) attitudes (ATT), or evaluations and beliefs about this behavior; and b) subjective norms (SN), or the normative reasoning related to the social pressure to engage in behavior expected by the group of belonging (Figure 1).

Note: ATT = attitude; SN = subjective norm; PI = purchase intention; PB = purchase behavior.

Figure 1 Theory of reasoned action.

Theory of planned behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1985). When restrictions over actions cannot be predicted based only on intention (TRA model), the perceived behavioral control (PBC) allows us to examine the influence of personal, social, and non-volitive determinants over the purchase intention, something that greatly increases the predictability of the TRA model (Han et al., 2010). In the case of green products consumption, the TPB model evaluates the potential relationship between the behavior intention and the psychological/cognitive determinants (Jebarajakirthy & Lobo, 2014) (Figure 2).

Note: ATT = attitude; SN = subjective norm; PBC = perceived behavioral control; PI = purchase intention; PB = purchase behavior.

Figure 2 Theory of planned behavior.

Extended theory of planned behavior (ETPB) (Paul et al., 2016). Although TPB presents a vast amount of empirical evidence backed by diverse fields and areas (Ajzen, 2006), for Paul et al. (2016) the context where potential ecological consumers are located (defined by factors such as country and social group) can condition the voluntary control over behaviors. Thus, incorporating to the model the environmental concern (EC) as a determining factor provides a better understanding of green products purchase intention in developing countries (Paul et al., 2016). EC is defined as the set of people’s values, feelings, and beliefs for the environment (and its socio-natural assemblage), their emerging problems, and their individual and collective willingness to solve them (López-Miguens et al., 2014) (Figure 3). Considering the role that context can have over ecological consumption, it is likely that consumers in developing countries do not have or perceive a voluntary control over decisions related to green products purchase. Therefore, the applications of this type of models should be validated case to case (Paul et al., 2016).

Note: EC = environmental concern; ATT = attitude; SN = subjective norm; PBC = perceived behavioral control; PI = purchase intention; PB = purchase behavior.

Figure 3 Extended theory of planned behavior.

Against this background, the overall objective of this study is to compare the empirical adequacy of TRA, TPB, and ETPB models for green product purchase intention in Chilean population. In terms of the relevance of this work, it is important to note that psychological research on this topic is still incipient in Latin America (Medina, 2021), therefore it is necessary to develop and validate instruments and methodologies concordant with the main socioenvironmental issues that exist at regional and national levels (Reveco-Quiroz et al., 2022). To achieve this, we analyzed the reliability and validity of the GP (green products) scale in Chilean population, as the models based on these theories are country specific and difficult to understand outside their original context (Lee & Green, 1991; Paul et al., 2016). Finally, we expect that the results of this study provide relevant knowledge about the determining factors of pro-environmental behavior in Chilean consumers. This information, combined with the results of LCA studies and other environmental impact assessment tools, should form the basis for the successful implementation of policies that encourage sustainable consumption.

Methodology

This was a non-experimental, cross-sectional, descriptive, and correlational study that adapted and assessed the psychometric properties of a scale (León & Montero, 2015). In particular, it examined the adaptability, reliability, and validity of a scale that measures the intention to purchase green products (Paul et al., 2016).

Participants

The criteria used to select the sample size (n = 480) was established based on the recommendation of Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black (2010) considering a minimum of 15-20 participants per item for the realization of the structural equations model (SEM). The original scale for the determining factors of green products purchase intention (Paul et al. 2016) is made of 24 items. In this regard, we used a non-probabilistic sample by selecting 500 participants, which had to meet the following inclusion criteria: a) being 18 or more years old, b) residing in the Ñuble region (Chile), and c) voluntarily agreeing to participate in this study. The socio-demographic characteristics of the participants are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1 Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample divided by sex

| Female n (%) | Male n (%) | Total n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 328 (65.6) | 172 (34.4) | 500 (100) |

| Residence | |||

| Urban | 285 (57) | 150 (30) | 435 (87) |

| Rural | 43 (8.6) | 22 (4.4) | 65 (13) |

| Age | |||

| 18-30 | 109 (21.8) | 80 (16) | 189 (37.8) |

| 31-40 | 52 (10.4) | 26 (5.2) | 78 (15.6) |

| 41-50 | 87 (17.4) | 29 (5.8) | 116 (23.2) |

| 51 or more | 80 (16) | 37 (7.4) | 117 (23.4) |

| Educational Level Completed | |||

| Primary | 55 (11) | 26 (5.2) | 81 (16.2) |

| Secondary | 171 (34.2) | 97 (19.4) | 268 (53.6) |

| University | 102 (20.4) | 49 (9.8) | 151 (30.2) |

| Income | |||

| One minimum income * | 203 (40.6) | 81 (16.2) | 284 (56.8) |

| Two minimum incomes | 53 (10.6) | 31 (6.2) | 84 (16.8) |

| Three minimum incomes | 27 (5.4) | 18 (3.6) | 45 (9.0) |

| Four or more minimum incomes | 45 (9) | 42 (8.4) | 87 (17.4) |

| Employment | |||

| Unemployed and/or studying | 131 (26.2) | 52 (10.4) | 183 (36.6) |

| Simple jobs | 59 (11.8) | 33 (6.6) | 92 (18.4) |

| Technical jobs | 57 (11.4) | 39 (7.8) | 96 (19.2) |

| Professional jobs | 72 (14.4) | 41 (8.2) | 113 (22.6) |

| Highly specialized jobs | 9 (1.8) | 7 (1.4) | 16 (3.2) |

* Note: Since March 1, 2020 the gross amount is $318,000 Chilean pesos, equivalent to $476.56 dollars (Law No. 21.112).

Instruments

Sociodemographic survey. A sociodemographic characteristics instrument was elaborated. It included: a) place of residence, b) gender, c) age, d) educational level, e) monetary income, and f) employment, and was based on the survey format of the National Socio-Economic Characterization Survey (CASEN in Spanish) (Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia, 2018).

Green products scale. This instrument consists of 24 items derived from the extended theory of planned behavior proposed by Paul et al. (2016). The scale is subdivided into dimensions and consists of: a) three items of attitude (for example, “I like the idea of purchasing green products”); b) four items of subjective norm (for example “People who are important to me think that I should purchase green products”); c) seven items of perceived behavioral control (for example, “I believe I am capable of purchasing green products”); d) five items of environmental concern (for example, “I am very concerned about the environmental problems”); and e) five items of purchase intention (for example, “I will consider buying less polluting products in the future”). A five-point Likert scale was used for each item, where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. Regarding Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency, the five dimensions (constructs) of the original study presented high values in the range of α 0.79 and α 0.91.

Ethical considerations

The validation of the scale is part of the research project DIUBB 186009 3/I “Consumo sustentable de bolsas de transporte de productos en el comercio: evaluación ambiental del ciclo de vida asociado a los patrones del comportamiento de la población”, which was revised and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad del Bío-Bío Research Directorate.

Procedures

Down below we present the procedure performed to assess the psychometric properties of the scale:

Instrument administration. Data were collected by undergraduates of psychology and natural resources engineering programs, who were trained to apply the instruments considering the following aspects: a) clarification of objectives, b) an informed consent, c) confidentiality, d) application time, and e) emerging questions. The instrument was individually applied to householders or their spouses, provided that they met the inclusion criteria and were willing to participate in the study. The application was performed in a single moment between July and December 2018 in the respondents’ residence and had an average duration of 20 minutes. Before filling out the instrument, the participants read and signed an informed consent that contained information about the research and its objectives.

Statistical analysis. Different types of statistical analysis were implemented. They are described below:

Inter-rater reliability. Fleiss’ kappa coefficient was initially applied to the analysis of content validity agreement, a variable used for more than two raters (Falotico & Quatto, 2015). However, this coefficient could present biased results and not be a good indicator of inter-rater agreement, as evidenced by the prevalence of higher categories over the lower ones (Abad et al., 2011). For this reason, the Randolph’s free-Marginal multirater kappa (2005) was used, with Gwet’s variance formula (2010), which was obtained using an online kappa calculator (Randolph, 2008). Regarding the interpretation of this coefficient, its minimum value is 0 and its maximum is 1, with the following strength of agreement ranges: a) 0.00 = poor, b) 0.10 - 0.20 = slight, c) 0.21 - 0.40 = fair, d) 0.41 - 0.60 = moderate, e) 0.61 - 0.80 = substantial, f) 0.81 - 1.0 = Almost perfect (Landis & Koch, 1977).

Descriptive statistics and internal consistency reliability. Originally, a descriptive analysis was carried out for each item and its respective dimension. Subsequently, the omega coefficient (ω) was used in the internal consistency analysis for the five dimensions of the scale (McDonald, 1999). The corrected item-total correlation was examined through the free graphic software JASP version 0.11.1.

Convergent and discriminant validity. On the one hand, for convergent validity, Bagozzi, Yi and Phillips (1991) recommend that the standardized factor loadings, at a subscale-item level, should be significant and present values higher than 0.5, as well as a composite reliability higher than 0.7 (Hair et al., 2010). On the other hand, for discriminant validity, Fornell and Lacker (1981) suggest verifying if the square root of the average variance extracted √AVE of each dimension is higher than the square of the correlations between sub-dimensions.

Structural Equations Modeling (SEM). A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was carried out to compare the theoretical models about the structure of green products purchase behavior (Hair et al., 2010), using the Mplus v8 software. For the CFA, the robust weighted least squares method (ULSMV) through polychoric correlations was used to correct possible problems related to the normal distribution. To contrast model validity and to make a comparison between rival models (Hair et al., 2010), the following goodness fit indexes were calculated: a) χ² (chi-square), b) χ2 /df (coefficient of χ² divided by the degrees of freedom), c) robust comparative fit index (CFI), d) TLI (Tucker-Lewis index), and e) root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). According to Browne and Cudeck (1993) and Hair et al. (2010), a model is adequate when it presents the following indexes ≥ 0.90, χ²/df between 2 and 5 and RMSEAS ≤ 0.08.

Results

Procedures of adaptation and validity of content of the scale

The original version of the scale was first translated to Spanish by the authors of this article and an English-Spanish translator. This process involved carrying out a semantic adaptation of its 24 items while trying to preserve the sense and clarity of the original questions. The scale was later sent to four faculty members of Chilean universities with five or more years of experience in teaching and research in the environmental field and a master’s or doctorate degree. These judges, who were intentionally selected, belonged to different disciplines: psychology n = 2, sociology n = 1, and environmental engineering n = 1. They received an e-mail with the instrument and the assessment form in June 2018 and a request for submission within two weeks. The four judges agreed voluntarily and free of charge to participate in the content validation of the instrument.

The assessment of the scale, grouped into the four original dimensions, was conducted for each item using the experts’ assessment form proposed by Escobar-Pérez and Cuervo-Martínez (2008) that includes the areas of sufficiency, clarity, coherence, and relevance, and establishes four evaluation options: does not meet the criterion, low level, moderate, and high level. The assessment also considered the judges’ qualitative observations for each item (Cassepp-Borges et al., 2010).

After tabulating the judges’ responses, the study determined the agreement degree between them through the kappa coefficient. Regarding the assessment of the adapted instrument, the calculation of the kappa coefficient considered the proportion of possible agreements that occurred in each dimension and estimated the strength of agreement magnitude. This was interpreted from slight (1), fair (3), and substantial (1) by the group of judges, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2 Agreement coefficient of each dimension of the scale

| Dimensions | Free-marginal kappa | IC 95% | Strength of agreement Interpretation (Landis & Koch, 1977) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 0.36 | 0.05 - 0.66 | Fair |

| Subjective norm | 0.21 | 0.11 - 0.32 | Fair |

| Perceived behavioral control | 0.14 | 0.06 - 0.22 | Slight |

| Environmental concern | 0.79 | 0.64 - 0.95 | Substantial |

| Purchase intention | 0.28 | 0.13 - 0.42 | Fair |

Afterwards, the strength of agreement between pairs of experts was calculated. This revealed a substantial level of agreement in the environmental concern subscale, followed by purchase intention and attitude, with consistencies that ranged from slight to substantial. In contrast, the subscales that presented the greatest disagreement were perceived behavioral control and subjective norm, as detailed in Table 3.

Table 3 Agreement coefficient by dimension between pair of judges

| Dimensions | Free-marginal-kappa - agreement by pair of judges | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-2* | 1-3 | 1-4 | 2-3 | 2-4 | 3-4 | |

| Attitude | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.20 | 0.47 | 0.07 |

| Subjective norm | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.38 | 0.59 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| Perceived behavioral control | -0.15 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.58 | 0.21 | 0.03 |

| Environmental concern | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 1 |

| Purchase intention | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.42 | 0.83 | 0.25 | 0.42 |

Note: * Number of each judge (judge 1, judge 2, judge 3, and judge 4).

Finally, a substantial strength of agreement was found in clarity, while the area related to sufficiency presented a moderate strength of agreement. Relevance presented a fair strength of agreement and coherence showed a slight agreement. This is explained by the redundancy of certain items according to the judges (for example: similarities in the three attitude items, as well as the generality of item number 20 regarding environmental impact). This strength of agreement is represented in Table 4.

Table 4 Kappa coefficient in the four assessment areas of the judges

| Areas | Free-marginal-kappa | IC95% | Strength of agreement Interpretation (Landis & Koch, 1977) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sufficiency | 0.56 | 0.02 - 1.00 | Moderate |

| Clarity | 0.51 | 0.36 - 0.66 | Substantial |

| Coherence | 0.12 | -0.01 - 0.26 | Slight |

| Relevance | 0.37 | 0.23 - 0.51 | Fair |

Once the content was validated by this expert assessment and the qualitative recommendations were added, the writing of four items of the instrument was adjusted (1, 2, 3, and 20). Subsequently, a pilot test was conducted to assess the applicability/viability of the scale in a sample of 30 psychology students from the quantitative research methodology class and seven natural resources engineering students from the life cycle assessment class, both groups from the Universidad del Bío-Bío. This data was used to refine instructions, the application format, time, and other aspects that were later included. Appendix 1 presents the final version of the instrument used.

Descriptive statistics and internal consistency reliability

The assessment of the items’ averages, ranged between 2.68 and 4.53 and with standard deviations between 0.06 and 1.01, proofs the nonoccurrence of a “floor” (1) or “ceiling” (5) effect in any of the analyzed items. The initial item-subscale correlations were: a) attitude (between r = 0.63 and r = 0.68), b) subjective norm (between r = 0.50 and r = 0.76), c) perceived behavioral control (between r = -0.22 and r = 0.53), d) environmental concern (between r = 0.45 and r = 0.63), and e) purchase intention (between r = 0.57 and r = 0.74). Only item 14 of the perceived behavioral control subscale obtained a value lower than 0.30 (r = -0.22), therefore, this item was deleted, obtaining new item-scale correlations which ranged from r = 0.44 to r = 0.59. Regarding the subscale means, the dimensions of a) environmental concern (M = 4.48, SE = 0.22), b) attitude (M = 4.47, SE = 0.08), and c) purchase intention (M = 4.24, SE = 0.25) obtained the highest values, which meant a greater presence of these variables in the sample. The factors that presented the lowest means were the dimensions of c) subjective norm (M = 3.81, SE = 0.06) followed by d) perceived behavioral control (M = 4.02, SE = 0.40). Descriptive statistics and internal consistency coefficients are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5 Descriptive statistics and internal consistency of items and dimensions of the green products scale (n = 500)

| Subscale/item | M(SD) | Asymmetry | kurtosis | McDonald’s Omega ω | λ | AVE | Composite reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 4.47(0.08) | -1.07 | 1.50 | 0.81 | |||

| ATT1 | 4.48(0.64) | -1.86 | 1.60 | 0.703 | 0.833 | ||

| ATT2 | 4.53(0.63) | -1.54 | 4.05 | 0.754 | 0.851 | 0.719 | 0.8845 |

| ATT3 | 4.38(0.70) | -1.01 | 1.14 | 0.739 | 0.859 | ||

| Subjective norm | 3.81(0.06) | -4.30 | -0.03 | 0.85 | |||

| SN1 | 3.81(0.90) | -0.40 | -0.23 | 0.798 | 0.867 | ||

| SN2 | 3.87(0.87) | -0.37 | -0.38 | 0.787 | 0.899 | 0.745 | 0.9210 |

| SN3 | 3.82(0.98) | -0.80 | 0.34 | 0.866 | 0.898 | ||

| SN4 | 3.73(0.96) | -0.40 | -0.37 | 0.782 | 0.784 | ||

| Perceived behavioral control | 4.02(0.40) | -0.29 | -0.03 | 0.79 | |||

| PBC1 | 4.40(0.68) | -0.97 | 1.04 | 0.723 | 0.827 | ||

| PBC2 | 4.33(0.77) | -1.17 | 1.61 | 0.744 | 0.838 | ||

| PBC3 | 4.40(0.70) | -1.38 | 3.18 | 0.724 | 0.818 | 0.456 | 0.8216 |

| PBC4 | 3.74(0.98) | -0.66 | -0.06 | 0.773 | 0.589 | ||

| PBC5 | 3.50(1.01) | -0.32 | -0.76 | 0.791 | 0.353 | ||

| PBC6 | 3.76(0.92) | -0.63 | 0.03 | 0.779 | 0.454 | ||

| Environmental concern | 4.48(0.22) | -1.02 | 0.98 | 0.76 | |||

| EC1 | 4.23(0.77) | -1.09 | 1.82 | 0.730 | 0.152 | ||

| EC2 | 4.25(0.78) | -1.40 | 3.05 | 0.754 | -0.794 | ||

| EC3 | 4.57(0.68) | -1.80 | 3.81 | 0.717 | -0.767 | 0.376 | 0.6828 |

| EC4 | 4.66(0.59) | -1.90 | 4.28 | 0.674 | -0.529 | ||

| EC5 | 4.67(0.58) | -1.69 | 2.25 | 0.729 | -0.635 | ||

| Purchase intention | 4.24(0.25) | -0.63 | 0.09 | 0.86 | |||

| PI1 | 4.44(0.70) | -1.53 | 4.03 | 0.839 | 0.602 | ||

| PI2 | 4.31(0.73) | -1.06 | 1.86 | 0.817 | 0.750 | 0.564 | |

| PI3 | 3.81(0.90) | -0.50 | -0.09 | 0.849 | 0.842 | 0.9151 | |

| PI4 | 4.30(0.71) | -1.02 | 1.79 | 0.819 | 0.710 | ||

| PI5 | 4.33(0.79) | -1.32 | 2.40 | 0.804 | 0.825 |

Note: ATT = attitude; SN = subjective norm; PBC = perceived behavioral control; EC = environmental concern; PI = purchase intention; λ = factor loadings; AVE = average variance extracted.

Convergent and discriminant validity

Two approaches were used for the convergent validity analysis. The first one was based on Table 5, even though all the items presented statistically significant factor loadings regarding their dimensions. According to the criterion of Bagozzi et al. (1991) only 22 items obtained factor loadings over 0.5, except for PBC5 and EC1. The second approach was the average extracted variance (AEV), with values over 0.5 for the dimensions of attitude, subjective norm, and purchase intention, and lower values for perceived behavioral control and environmental concern. These values were complemented by composite reliability, obtaining values over 0.7 for all dimensions, except for environmental concern (Hair et al., 2010). Finally, in the case of discriminant validity, all the √AEV dimensions were higher than the square of the correlations (Table 6).

Table 6 Discriminant validity

| Dimensions | ATT | SN | PBC | EC | PI |

| Attitude (ATT) | 0.848 | ||||

| Subjective norm (SN) | 0.190 | 0.863 | |||

| Perceived behavioral control (PBC) | 0.282 | 0.195 | 0.676 | ||

| Environmental concern (EC) | 0.244 | 0.056 | 0.156 | 0.613 | |

| 0.292 | 0.132 | 0.384 | 0.382 | 0.751 |

Note: The diagonal values correspond to the square root of AEV for each dimension.

Model comparison: TRA, TPB, and ETPB

The construct validity of the three models was assessed through confirmatory factor analysis, hereinafter called CFA (Lloret-Segura et al., 2010). Following the rival models strategy (Hair et al., 2010), an assessment was conducted on the global fit criteria: a) absolute RMSEA, b) incremental CFI and TLI, and c) parsimony (χ2/df) for the three models (Table 7).

Table 7 Description of the models and their adequacy criteria

| Indexes FIT & R 2 | Recommended values | TRA | TPB | ETPB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | 139.254 | 329.494 | 495.825 | |

| gl | 46 | 122 | 209 | |

| χ2/gl | 2-5 | 3.027 | 2.700 | 2.372 |

| CFI | ≥0.9 | 0.977 | 0.960 | 0.965 |

| TLI | ≥0.9 | 0.967 | 0.950 | 0.958 |

| RMSEA | ≤0.08 | 0.064 | 0.058 | 0.052 |

| R2 | ||||

| ATT | 0.633 | 0.529 | 0.551 | |

| SN | 0.275 | 0.102 | 0.319 | |

| PBC | ____ | 0.471 | 0.747 | |

| EC | ____ | ___ | 0.820 |

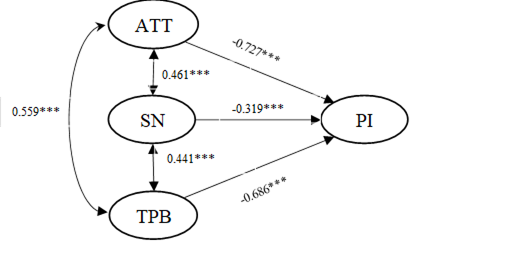

First, the TRA model presented the following values of unsatisfactory fits (χ2 = 249.705; df = 51; p < 0.001; χ2/df = 4.896; CFI = 0.952; TLI = 0.937; RMSEA = 0.088). In order to improve the model’s fit, it was re-specified based on the residual modification indices of the items related to the same construct (Lei & Wu, 2007) in the following pairs of correlations belonging to the same dimension: a) i6 and i4, b) i6 and i5, c) i22 and i20, d) i23 and i21, and e) i24 and i23. Once the model was re-specified (Figure 4), an adequate fit was obtained (χ2 = 139.254; df = 46; p < 0.001; χ2/df = 3.027; CFI = 0.977; TLI = 0.967; RMSEA = 0.064).

Second, the TPB model presented the following values of unsatisfactory fits (χ2 = 613.383; df = 129; p < 0.001; χ2/df = 4.754; CFI = 0.907; TLI = 0.890; RMSEA = 0.087). The model was re-specified, adding the following correlations: a) i13 and i12, b) i24 and i23, c) i6 and i4, d) i6 and i5, e) i11 and i9, f) i11 and i12, and g) i11 and i13. Once the model was re-specified (Figure 5), an adequate fit was obtained (χ2 = 329.494; df = 122; p < 0.001; χ2/df = 2.700; CFI = 0.960; TLI = 0.950; RMSEA = 0.058).

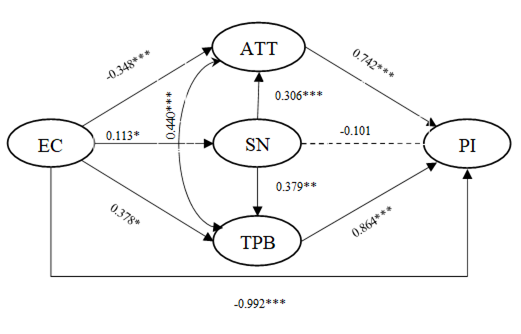

Finally, the results of the extended TPB presented the following values of unsatisfactory fits: χ2 = 886.897; df = 221; p < 0.001; χ2 /df = 4.013; CFI = 0.919; TLI = 0.907; RMSEA = 0.078. The model was re-specified by adding the theoretical relationship between ATT and PBC and the empirical correlations between residues: a) i13 and i12, b) i19 and i18, c) i22 and i21, d) i20 and i19, e) i6 and i4, f) i6 and i5, g) i20 and i18, h) i11 and i9, i) i10 and i8, j) i13 and i11, and k) i12 and i11. Once the model was re-specified (Figure 6), an adequate extended fit was obtained (χ2 = 495.825; df = 209; p < 0.001; χ2 /df = 2.372; CFI = 0.965; TLI = 0.958; RMSEA = 0.052).

Discussion

Our findings indicate that the extended TPB presents a better structural fit than TPB and TRA for the prediction of green products purchase intention in the studied sample of Chilean population, despite psychometric differences inside the environmental concern subscale. Likewise, this study confirmed the evidence of validity and reliability for the green products scale in the studied population.

In line with the study by Paul et al. (2016), the ETPB model is useful to explain the consumption behavior intention for green products based on a triple bottom line. Its main contribution is the indirect effect of EC, validating the initial hypothesis that positive PBC and ATT results in a higher probability of green products PI. Even though we observed that PBC and ATT are the main predictive variables, SN does not present a relevant influence over the intention of green product purchase, similar to previous studies in Filipino (Tarkiainen & Sundqvist, 2005), Indian (Paul et al., 2016), and Indonesian (Asih et al., 2020) population. In other words, the purchase intention of green products in the studied Chilean population is mainly explained by personal values and beliefs over the environment, and not by the social pressure or the potential approval of significant persons. Nevertheless, it is important to mention that in previous studies using the TPB model, subjective norm has been observed to be the variable with the lowest weight, both at a general level (Ajzen, 1991), and in applications to green marketing (Paul et al., 2016; Tarkiainen & Sundqvist, 2005).

Our results also suggest that the instrument presents an adequate reliability in the five assessed dimensions. Only environmental concern showed a fair range of internal consistency, while the other sub-dimensions are in the range of substantial and almost perfect. In conceptual terms, future studies should strengthen the operationalization of the environmental concern variable, incorporating indicators linked to moral obligation (values and ethic) and emotions, as these represent influential elements over the attitudes and personal intentions of green product purchase and consumption (Ghose & Chandra, 2020). Regarding methodology, it is necessary to offer new evidence of reliability for the application of test-retest. This a relevant step to refine and broaden the results.

In terms of validity, the results showed evidence based on the convergent, discriminant, and confirmatory factor structure content. Regarding the first one, the information provided by the inter-rater agreement assessment suggests that the agreement ranges fluctuate between fair and substantial, except for the perceived behavioral control sub-scale. Even though subsequent intra-item and inter-scale modifications were made -they presented psychometric validity and reliability- future studies should incorporate more sensitive operationalization elements for measuring the variable related to the locus of control.

In relation to convergent and discriminant validity, the study found that the perceived behavioral control and environmental concern sub-scales were the only ones with marginal values lower than expected according to the average variance extracted. This was complemented by the composite reliability analysis, which showed lower than expected values only for the environmental concern sub-scale. In this regard, it has been shown that the level of environmental concern depends on the consumers’ home country; being developed countries the ones with greater levels of concern (Singh & Gupta, 2013). However, this is inconsistent with the high levels of environmental concern shown by the Chilean population (EDF, 2019). A possible explanation for this inconsistency is the type of sample used by Paul et al.’s research (2016), where a high level of education was used as a control measure for a better understanding of the situation (Hedlund, 2011).

Finally, it is necessary to explain the limitations of this study. The first one is related to the characteristics of the sample, which differ from the original study in terms of educational level and income. This can be solved with a stratified probability sampling in future research. At the same time, even if there is no concluding evidence with respect to the role of the sociodemographic characteristics over environmental concern, it is important to study different cultural, religious, and economical contexts (Ghose & Chandra, 2020). Furthermore, the replication of this study in other Latin American countries where population and environmental concern are growing is also desirable (Sandoval Díaz et al., 2020), as it would allow for a deeper understanding of the sociocultural and environmental determinants of green product purchase intention (Hazaea et al., 2022).

Second, even though the theory of planned behavior is the most utilized model in literature to analyze the personal and behavioral factors of green product purchasing, future studies should incorporate aspects related to the type of product (and their publicity attributes) and social, environmental, and emotional factors that influence the consumers (Hazaea et al., 2022).

The third limitation of this study, also shared by Paul et al.’s investigation (2016), is the fact that green products are considered as a whole. Future research should specify the type of product and include attributes such as recyclability, organic production methods, low embodied carbon, etc. Finally, it is expected that the incorporation of knowledge about the psychosocial variables involved in the green products purchase process can facilitate the communication of relevant environmental information to consumers. Even though tools such as LCA can provide detailed and objective information about the environmental profile of products, the way in which that highly technical data is communicated to the population is relevant to effectively direct their behavior towards more sustainable practices (Polizzi et al., 2016). Our results suggests that the communication of this information should be oriented towards influencing purchase intention through the environmental concern/attitude pathway and highlights the importance of considering the population’s perceived limitations about their potential for buying green product, including sociocultural, economic, educational, and other relevant factors affecting behavior (Klöckner, 2015). Given the lack of studies of concurrent and prospective validity, it is important to advance in a culture of integral evaluation to generate models that could adequately predict purchase intention, with results that could be incorporated in decision-making processes such as the design and implementation of policies that requires a societal-wide adoption in order to reduce the environmental impact of consumption. Examples of these policies include limitations on single-use products (such as carrier bags), subsidies to promote energy-efficient appliances, strategies to promote car-sharing, and mechanisms to foster the adoption of sustainable means of transportation, among others (Klöckner, 2015). Given the increasing relevance of these policies in Chile, such as the Ley 21.368 (2021) that limits the handing over of single-use plastics in commerce, understanding the psychological aspects related to their adoption by the population is of paramount relevance for a successful implementation.

Overall, the results of this study show that the ETPB theoretical constructs are relevant for the studied population. This implies that in order to effectively communicate environmental information collected from LCA and other environmental analysis tools, communication strategies should include messages oriented to influence cognitive-affective, contextual, and sociocultural factors related to the purchase decision process.