INTRODUCTION

The hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) is classified as critically endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the Libro rojo de reptiles de Colombia (Red book of Colombian reptiles) (Meylan and Donelly 1999; Mortimer and Donelly, 2008; Barrientos-Muñoz et al., 2015). In addition, the species features in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, CITES (Rhodin et al., 2018), Appendices I and II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species (CMS) and in Appendix II of the Protocol for Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife, SPAW (Barrientos-Muñoz et al., 2020).

However, despite the fact it is protected by legislation and by national and international treaties, it is the marine turtle species that faces the highest levels of anthropic pressure (Meylan and Donelly 1999; Mortimer and Donelly, 2008; Barrientos-Muñoz et al., 2015). In addition to the consumption of its meat and eggs, the principal reason for its critical status both internationally and locally is illegal trafficking of its shell for the production of artisan products, kitchen utensils and cock fighting spurs (Meylan, 1999; Reuter and Allan, 2006; Barrientos-Muñoz et al., 2015, 2020; Ramírez-Gallego and Barrientos-Muñoz, 2020, 2021).

The hawksbill turtle is the most widely distributed marine turtle species found on Colombia´s nesting beaches —although few specific population studies for the species have been conducted— and is found in all the departments comprising the Caribbean basin, though it is less abundant in seasonal nesting sites (Ceballos-Fonseca, 2004; Barrientos-Muñoz et al., 2015). Contributions to our understanding of the hawksbill turtle are principally associated with sightings in nesting areas and/or, sporadically, in the water during the monitoring of other species, not necessarily marine turtles (McCormick, 1997, 1998; Rincón et al., 2001; Arcos et al., 2002; Ceballos-Fonseca, 2004; Rincón-Díaz and Rodríguez-Zárate, 2004; Barrientos-Muñoz et al., 2015).

Although no population studies of the species have been carried out in Rincón del Mar, it is known that the nesting season of the hawksbill turtle in the Colombian Caribbean extends from April to November (Kaufmann, 1967), with two peak periods in May and September (Barrientos-Muñoz et al., 2015). Currently, the Colombian department with the greatest number of hawksbill turtle nests is the Archipelago of San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina (Eckert and Eckert, 2019; Ramírez-Gallego and Barrientos-Muñoz, 2020b; Barrientos-Muñoz et al., 2020).

For its part, in the sub-region of Morrosquillo, department of Sucre, historically the hawksbill turtle has been recorded as nesting sporadically in El Francés, Isla Palma, Punta Seca, Balsillas and Altos de Julio (Rueda, 1987; Ceballos-Fonseca, 2004; Caraballo et al., 2008; Duque et al., 2011; Barrientos-Muñoz et al., 2015). In addition to the nesting zones, the presence of extensive meadows of marine grass and coral reefs has enabled the identification of multiple life stages of marine turtles in their feeding, resting and/or reproduction zones (Rincón-Díaz and Rodríguez-Zárate, 2004; Moncada et al., 2019). A diversity of marine and beach habitats is vital to the conservation of marine turtles in this extensive region (Rincón-Díaz and Rodríguez-Zárate, 2004; Moncada et al., 2019). However, hunting to obtain shells or for the consumption or sale of meat and/or eggs, habitat loss, coastal erosion and contamination by plastics are among the principal threats facing the species (Caraballo et al., 2008; Barrientos-Muñoz et al., 2015, 2020).

The Unidad Ambiental Costera Estuarina del Río Sinú y Golfo de Morrosquillo is a coastal planning unit that includes national and regional protected areas. Together, these protected areas make up the Subsistema de Áreas Marinas Protegidas (Sub-system of Protected Marine Areas - SAMP): PNN Corales del Rosario y San Bernardo, PNN Corales de Profundidad, DRMI Bahía Cispata, La Balsa, Tinajones and neighboring sectors to the delta of the Sinú river, PNR Boca de Guacamayas, DRMI Ciénaga de la Caimanera and the DRMI Sabanetica, Chichimán, Rincón del Mar and Berrugas (Carsucre) (Figure 1). In fulfilment of the Aichi Target to increase protected areas by 10% by the current year this will strengthen the National System of Protected Areas (SINAP) and the National Environmental Policy towards Sustainable Development of Oceanic Spaces, Coastal and Island Regions of Colombia (PNAOCI), which will create a mechanism for the protection of marine and coastal biodiversity, including marine turtles (INVEMAR-CVS, 2012; SIRAP, 2013; Cardique et al., 2016).

For the last five years, the Autonomous Regional Corporation of Sucre, Carsucre, the body responsible for environmental protection in the study area, has sought to implement control and monitoring measures in order to reduce the use of turtle nets in its area of jurisdiction. Fishing grounds dedicated to the capture of marine turtles (Chelonia mydas, the Green Sea Turtle, and Eretmochelys imbricata) for human consumption and commercialization have been found in the island of Boquerón (Carsucre, 2017). It is, therefore, of urgent importance to continue with control and monitoring efforts and to contribute to increasing understanding of marine turtles in the department of Sucre.

After a decade of absence, nine hawksbill nests were recorded in Rincón del Mar in 2018. This led to the implementation by Carsucre and the Fundación Tortugas del Mar of the project “Integrated management of the UAC River Sinú-Gulf of Morrosquillo estuarine”, this project involves community strengthening, environmental education and the systematic monitoring of hawksbill turtle nesting sites in Rincón del Mar. Systematic monitoring was conducted during the 2018 and 2019 nesting seasons in order to contribute to understanding of the ecology of the species’ nesting in the area.

STUDY AREA

Rincón del Mar (9º 46,5’, 23” N, 75º 38,31’, 30” W) is located in the municipality of San Onofre, department of Sucre (Figure 2). It has a dry climate, with temperatures that range between 24º C and 38° C and annual rainfall that oscillates between 800 and 1000 mm. It has a bimodal rainfall regime, with two dry periods between December and April, and June and July; the other months are dry (Cusado-Zapa and González-Pérez, 2010).

Its coastal littoral zone is characterized by shallow intermediate beaches and high energy waves. The sand is white-gray in tone and is composed of 27.7 % large-grained (DE = 0,5 mm) and 56% medium (DE = 0.25 mm) carbonate materials (Caraballo et al., 2008).

Human settlement in the area is dedicated principally to tourism and in some places mangrove ecosystems persist, dominated by red and white mangroves (Rhizophora mangle and Laguncularia racemose) and by other less widely distributed species such as the sea grape (Coccoloba uvifera), portia tree (Thespesia populnea), Caribbean spider lily (Hymenocallis caribaea) and tropical almond (Terminalia catappa) (Ulloa et al., 2016). In the surrounding maritime area, ecosystems are found consisting of meadows of phanerogams and coral reefs, which have been identified as feeding and reproduction zones for the marine turtles that pass through the area (Rincón-Díaz and Rodríguez-Zárate, 2004).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Monitoring

Daytime and nocturnal patrols were carried out between July and September 2018 and 2019 (the months in which the likelihood of nesting was greatest, according to local experts). The patrols took place in two sectors. The northern sector, 2.8 km long, comprised of the beaches of Punta Rincón and Chichimán (9° 46’ 26.43” N, 75° 38’ 43.54” W - 9° 47’ 32.43” N, 75° 37’ 41.76” W), while the second, 6.9 km long, corresponded to the area between Balsillas and Boca de Ana Gómez (9° 45’ 47.53” N, 75° 38’ 27.36” W - 9° 43’ 27.66” N, 75° 41’ 3.95” W). The northern sector was only monitored for a short period due to low levels of activity of the turtles and public order problems (Figure 2). The nocturnal patrols were carried out between 20:00 and 23:00 h and looked for tracks and/or laying females. The daytime patrols were carried out between 05:00 and 08:00 h and were intended to record turtle tracks that had not been found the night before, with intention of verifying successful nesting events.

Recording and protecting nests

All the nests recorded were left in situ and monitored daily at night and in the mornings. When a nest was identified, signs were posted, its location was registered using GPS (Gpsmap 64S), along with the time and date the eggs were laid and the distance of the nest from the high tide line. Subsequently the nests were protected using 2 m square plastic cages, 60 cm in height. Nests that were clearly vulnerable to wave damage during the incubation period were protected by barriers made out of sandbags filled with sand from the beach, which was spread out again after the nest was vacated.

After day 40 of incubation, nests were inspected several times a day, to look for evidence of hatching. When signs were identified that hatchlings had left the nest, a few hours - up to a maximum of 24 - were left before beginning excavation.

Clutch productivity

Twenty-four hours after the hatchlings emerged and made their way to the sea, the nest site was excavated in order to determine hatching and emergence success. During the excavation process empty shells were counted (˃50 % complete) (S), as were unhatched eggs without any obvious embryonic development (UD), unhatched full-term embryos (UHT), depredated eggs (P), living hatchlings that were found trapped in the nest and/or below the neck (L), dead hatchlings that had succeeded in exiting the shell (D) and unhatched eggs (UH) (Miller, 1999). These latter were classified according to four categories of embryo development (Chacón et al., 2007).

Hatching success was estimated using the following formula: Hatching Success (%) = S / (S + UD + UH + UHT + P) * 100. Similarly, the following formula was used to calculate Emergence Success (%) = C - (L + D) / (S + UD + UH + UHT + P) * 100 (Miller, 1999).

Living hatchlings found within the nest were rescued and released in the cool of the early hours of the morning or at sunset, with the participation of the Rincón del Mar community. After the excavation process was completed, the depth and width of nests were measured along with their distance from the tide line. In addition, field notes were taken of the flora and fauna associated with the nest.

Hatchling biometry

Ten hatchlings were selected from each clutch. These were weighed using digital scales (Digital Pocket MH-500; precision: 0.1 g) and straight carapace length (SCL) and straight carapace width (SCW) measured using a 15 cm caliper gauge (Rey Plastic, CLP06U; precision: 0.05 mm) (Chacón et al., 2007). The hatchlings were subsequently released.

Environmental education

Working groups of local experts were set up, with responsibility for participatory monitoring of the northern and southern sectors. Workshops were also organized with the Rincón del Mar community, focused on awareness-raising, community strengthening, turtle release, and beach cleaning.

Threats

Natural and anthropic threats were identified on the basis of field visits and information provided by Carsucre, fruit of its control and monitoring activities in the zone. The tensor data obtained was recorded in a table and evaluated using a scale from zero to three (None: 0, Low: 1, Medium: 2, High: 3), using the method proposed by Rincón-Díaz and Rodríguez-Zárate (2004).

RESULTS

Monitoring

The two-year research process involved 246 person days of six h each (July to October), for a total during the 2018 and 2019 nesting seasons of 1476 h dedicated to daytime and nocturnal patrols.

Recording and protecting nests

A total of six hawksbill turtle nests were recorded, five in 2018 and one in 2019, all between July and September. One nest (20 %) was raided in 2018 and its eggs taken for food, while no clutches were lost in 2019. The beaches visited by laying females were all in the southern sector (between Balsillas and Boca de Ana Gómez); eggs were laid in all nests (Figure 2).

Clutch productivity

A total of 761 eggs were laid, with an average of 152.2 ± 15.5 eggs per nest (n = 5; Table 1). A total of 591 hatchlings reached the sea, of which 569 made it alone. 22 hatchlings (3.72 %) were rescued from entanglement among roots, eggs and shells.

Mean hatching success was 78.2 ± 12,4 % (range 62.8 - 91.0; n = 5) (Table 1), while mean emergence success was 74.7 ± 14.1 % (range 59.3 - 89.7; n = 5) (Table 1). The mean incubation period was 54 ± 7.8 days (range 47 - 63; n = 4) (Table 1).

The greatest mortality levels during incubation occurred during embryo development (13 %), while eggs without apparent development (UD) accounted for 8.8 % of the total (n = 5 nests; Table 2).

Table 2 Categories of unhatched eggs (UH) (subdivided into Stages I, II, III and IV) and eggs with no apparent development (UD) during the excavation of E. imbricata nests in Rincón del Mar, Sucre.

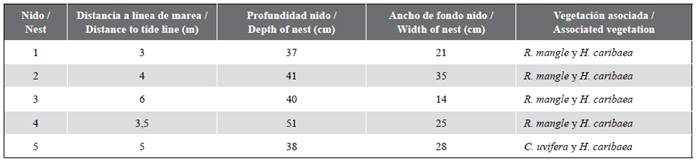

In terms of size, the nests had a mean depth of 41.4 ± 5,6 cm and width of 24.6 ± 7,8 cm and a distance from the tide line of 9.7 ± 12.5 m (n = 5; Table 3). Clutches 1, 2, 3 and 4 were laid in areas of R. mangle and H. caribaea. They were surrounded by a mosaic of habitats made up of a lacustrine complex lying parallel to the coastline, with the result that the lower eggs in the clutches entered into contact with the phreatic zone. For its part, nest 5 was found beneath C. uvifera and H. caribaea (Table 3). In general, nests were found in areas of shade provided by the tree canopy and beneath a layer of fallen leaves.

The fauna observed in the nesting area consisted principally of birds of the species Megaceryle torquata, Pelecanus occidentalis, Quiscalus mexicanus, Egretta tricolor, E. thula, Milvago chimachima, Sterna hirundo, Thalasseus maximus, T. sandvicensi and Fregata magnificens. In terms of mammalian fauna, Procyon cancrivorus was found, along with domestic animals such as dogs and pigs.

Hatchling biometry

Ten hatchlings were selected from each clutch, with average LRC dimensions of 4.0 (± 0.4) cm, ARC of 2.9 (± 0.2) cm and total weight of 15.4 (± 0.5) g (Table 4).

Environmental education

The Guardianes de las Tortugas de Rincón del Mar (Guardians of the Turtles of Rincón del Mar) were established, provided with their own logo and with the equipment required to carry out daytime and nocturnal patrols. The intention was to strengthen a sense of ownership and establish a process of participatory community monitoring. Twelve adults took part in this process.

A total of eight workshops and training sessions were organized on the biology of marine turtles, monitoring techniques and management, with the participation of the general population of Rincón del Mar. A total of 24 people participated in these community strengthening processes. An interinstitutional and intersectoral workshop was organized with international peers in Rincón del Mar, with the participation of 28 individuals from five different organizations.

Two releases of hatchlings were organized, jointly with the Rincón del Mar school and the local environmental group Titanes Ecológicos. A total of 30 community members, including children and adults, took part in these release events. Four awareness-raising activities were organized in the Rincón del Mar area, involving the distribution of leaflets and posters in strategic locations such as shops and hotels, with the aim of discouraging consumption of hawksbill turtle meat and eggs and of using its shell for making artisanal pieces, kitchen utensils and cock fighting spurs. Finally, two beach cleaning events were held in the sector of Punta Gorda, with the participation of 12 residents of Rincón del Mar, and an information video about the project was produced as part of the outreach process.

Threats

In 2019 a laying female was killed in the northern sector (between the beaches of Punta Rincón and Chichimán) and in 2018 a clutch of eggs was taken in the southern sector (between Balsillas and Boca de Ana Gómez). In addition, 14 natural and anthropic threats were identified in Rincón del Mar. Coastal erosion, depredation by domestic (dogs and pigs) and wild (racoons) animals, solid waste pollution, obstacles on the beaches, human transit and destructive fishing practices were identified as representing “High” levels of threat (Table 5). A categorization of the beaches identified Chichimán beach as facing a “High” degree of risk, Boca de Ana Gómez “Medium”, and Balsillas and Punta Gorda “Low” (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

Systematic daytime and nocturnal monitoring of the nesting sites of the hawksbill turtle is indispensable if the current status of the species in Colombia is to be understood. Therefore, like Barrientos et al. (2015), the authors recommend continuing with a standardized monitoring process of the species in Rincón del Mar, in order to determine the trends of the reproductive population in the area. The frequency and kind of monitoring, and the efforts put into the monitoring process will decide its effectiveness in identifying the current situation of the species and the areas on which future monitoring should focus. Therefore, in places such as Rincón del Mar, which are difficult to reach and where nesting is sporadic, local researchers with community roots are indispensable to this kind of monitoring, which recorded the laying of six clutches during the principal nesting months.

The size of the clutches is similar to those reported in other studies of the hawksbill turtle in the Caribbean and Pacific coastal regions of the Americas (Table 6). Hatching success (78.2 %) is higher in Rincón del Mar than the levels reported by Chacón et al. (2004), Colombia Marina (2007), Hancock (2008), Gerhartz-Muro et al. (2019) and Liles et al. (2019), including a prior estimation for the same area by Caraballo et al. (2008) (Table 6). This finding suggests that the beaches of Rincón del Mar provide optimal conditions for complete embryonic development to occur in nests and for high rates of survival. Among the determining factors for the survival of clutches are humidity, temperature, sand type and the slope and extension of beaches (Bolongaro et al., 2010; Piedra-Castro and Morales-Cerdas, 2015). It is probable that the presence of native vegetation on the beaches of Rincón del Mar (Table 3) ensures ideal conditions in nesting zones, which are vital to hatching success of this species, as they help maintain stable microclimatic conditions.

Table 6 Summary of average values of clutch size (eggs), hatching success (%) (mean ± SD and n) of E. imbricata in Rincón del Mar, compared to other studies on the Caribbean and Pacific coastal regions. n.r. = not registered.

On the other hand, the biometric measures in Rincón del Mar (LRC of 4.0 ± 0.4 cm, ARC of 2.9 ± 0.2 cm and total weight of 15.4 ± 0.5 g) are similar to those of other studies conducted in Pacific and Caribbean coastal regions (Kaufmann, 1975; Chacón et al., 2004; Joya and Molina, 2006; Hancock, 2008; Liles et al., 2019) (Table 4).

Environmental education, the participation of the Rincón del Mar community and the interinstitutional activities carried out were indispensable to the protection of the nests in situ up to the point of hatching. Community strengthening activities focused on the importance of the hawksbill turtle provided incentives to inhabitants to support actions to protect the species. Community inclusion and participation are an important step towards the conservation of marine turtles, as the local population is fundamental to monitoring, bearing in mind the infrequency of nests in the sector and their importance in the interconnections with other neighboring marine coastal areas. Thus, as in other parts of the world, where long-term participatory processes have stabilized or even increased marine turtle populations (Godley et al., 2020), it is to be hoped that the continuation of these actions will consolidate the sense of ownership of the community and coordination with environmental protection groups and/or agencies.

Finally, of the threats to the nesting zones in Rincón del Mar, the most serious include coastal erosion, the depredation of nests and solid waste pollution, all of which had previously been identified by Caraballo et al. (2008) and by Rincón-Díaz and Rodríguez-Zárate (2004) for the archipelago of San Bernardo. In the village of Rincón del Mar, coastal erosion represents a medium to high threat (Corporación Ecoversa, 2018), principally in the northern sector towards Chichimán, despite the fact that it is here that the most extensive beaches are found and the vegetation is most consolidated (Caraballo et al., 2008). The greatest degree of threat in Chichimán is probably the result of the accelerated loss of natural barriers along the coastline, such as mangroves, marine grasses and coral formations, alongside the limited role of the authorities, due to the public order situation that still characterizes the area. Similarly, because of erosion in the sector of Punta Gorda, sandbags were required to protect the nests from being washed away by the sea.

In terms of the depredation of nests, the presence on the nesting beaches of domestic animals such as dogs and pigs is alarming, as they represent a risk to laying marine turtle colonies (Kontos 1985, 1987, 1988; Richardson, 1990; Suganuma, 2005; Andrews et al., 2006; Meylan et al., 2006; Whytlaw, 2013; Engeman et. al. 2016, 2019). On the other hand, the consumption and commercialization of marine turtle clutches also remains a common practice, as it is also in other parts of the country, including in areas that benefit from some form of protection (Rincón-Díaz and Rodríguez-Zárate, 2004; Barrientos et al., 2013, 2014, 2015, 2020; Moreno-Munar et al., 2014). An example of this occurred during the period reported here, when, despite the fencing off and labeling of nests, one was raided. This demonstrates the high degree of exposure to depredation by outside species or human beings and the need to continue with monitoring, protection and awareness-raising activities in the area.

The capture of adult turtles for human consumption and the commercialization of their shells in the context of tortoiseshell smuggling also represent a threat to the species in Rincón del Mar (Caraballo et al., 2008), as it does in the rest of the Caribbean coast of Colombia: the country where the second highest number of hawksbill turtles in the world -an estimated 600- is captured annually (Campbell, 2014; Humber et al., 2014; Barrientos et al., 2015, 2020; Ramírez-Gallego and Barrientos-Muñoz, 2020a, 2021). In the case of the department of Sucre, the Isla de Boquerón has been identified as a major center for the capture of green and hawksbill turtles using the direct method of turtle nets (Rincón-Díaz and Rodríguez-Zárate, 2004), while in Sabanetica they are an incidental catch of fishing using gillnets. In response to this, Carsucre (2017) decommissioned 6600 m of turtle nets between 2015 and 2017 in the area under its jurisdiction and has proposed the establishment of the Regional Integrated Management District of Sabanetica, Chichimán, Rincón del Mar and Berrugas as a mechanism to protect the area for the conservation of the hawksbill turtle.

Solid waste pollution is also a major concern, as a large amount of plastic is found on the beaches. This has a potential effect on different properties of the nests, including temperature and permeability and has a direct impact on laying females and hatchlings by causing suffocation or presenting physical obstacles (Nelms et al., 2015).

Other factors identified in the field with indirect effects that require attention include the employment of destructive fishing techniques such as chinchorros playeros (beach seines, or cast nets) and dynamite in coral reef areas, habitat loss caused by coastal erosion, illegal felling of mangroves and coastal development, All of these act synergically to transform the ecosystems of the area, affecting the laying process by reducing available space. They also produce changes in the characteristics of the environment (sand composition, provision of shade by vegetation) that might reduce hatching and emergence success.

CONCLUSIONS

The beaches of Colombia’s Caribbean mainland on which the hawksbill turtle nests are few and nesting is sporadic. In Rincón del Mar and surrounding areas nests are not abundant. However, despite the local threats, E. imbricata continues using these beaches to lay its eggs. Consequently, as the zone hosts the third highest number of continental beaches on which hawksbill turtles nest in the country, it is of vital importance to strengthen protection processes by defining conservation mechanisms based on community participation, alongside interinstitutional and intersectoral approaches.

On the other hand, the geomorphological conditions of the beaches and the composition of their vegetation might be exerting an influence that helps maintain the philopatry of the species, permitting the females, also, to select the ideal spot to lay their eggs and to preserve their nesting sites in situ, with a high degree of reproductive success, as has been shown in this study. However, it has been observed that some beaches are being modified, not only in terms of their environmental variables, but also as a result of anthropic influences.

These beaches are key sites for the protection of the most critical stages in the life cycle of E. imbricata; they favor the conservation of the species in this extensive region, which consists of a mosaic of sometimes overlapping protected marine and coastal areas, including the Área Marina Protegida Archipiélago del Rosario y San Bernardo, the Parque Nacional Natural Los Corales del Rosario y de San Bernardo and the DRMI Sabanetica, Chichimán, Rincón del Mar y Berrugas (currently in the process of being established). It is therefore urgently important to establish an interinstitutional and intersectoral protection plan.

This species management plan should include the provision of permanent financial resources to ensure long-term monitoring, the saturation tagging and satellite transmission required to understand their use of habitats and the level of connectivity between these areas, an environmental education program that reaches the entire community and the development of a program offering local economic alternatives that would help eliminate the exploitation of hawksbill turtle byproducts.

text in

text in