INTRODUCTION

The Colombian fishery and aquaculture industries generates more than 50,000 direct jobs, which are dedicated to aquaculture, capture, and processing tasks in inland plants (Esquivel and Plata, 2014). Moreover, there are nearly 197,500 indirect jobs that participate in vessel unloading and preparation, product transportation, maintenance, repairs, among others, as well as 75,000 people linked to the commercialization process in both national and exports contexts (Esquivel and Plata, 2014). A large percentage of fishery activities is located in some of the poorest regions of Colombia, which are notably home to afro-descendent and indigenous communities, as well as to people displaced by the internal conflicts undergone by the country since the 1940s (OCDE, 2016). In addition, this activity has a strong gender role division, where women participate in tasks that take place inland and require abundant skills and time (Villa-Cascos et al., 2007), such as fishing net elaboration and repair and fishery products processing and commercialization, although they also participate in the collection and direct capture of different species (Thomas-Sánchez and Pis, 2019).

It is important to consider the local context of the Colombian Pacific, where women often take care of the family and are responsible for household finances and food supply. Therefore, gender inequality not only affects women’s livelihoods, but also those of the household and the community (Weeratunge et al., 2010; O’Neill et al., 2018). This situation brings about the need to understand differentiated roles and participation in the use and management of marine resources (Rohe et al., 2018), in order to achieve greater social inclusion in the programs and policies for strengthening the fishery economic sector in Colombia.

In the Colombian Pacific, a large part of fish, crustaceans, and mollusks commercialization is carried out by women known as platoneras. Specifically in the district of Buenaventura, street sale of fish and mollusks consolidated in La Playita neighborhood, where platoneras exhibited these products along with bananas and fruits in a colorful tropical environment that disappeared with the port’s urban transformations (Ministerio de Cultura, 2017). These transformations included the declaration of Buenaventura as a Special Economic Zone for Exports, since, in 2000, it mobilized 40% of the containers shipped and landed in Colombia (Cámara de Comercio de Buenaventura, 2008). Even though this type of commercialization has changed, the role of platoneras is still valid, as evidenced in recent analyses of the value chain of industrial shrimp trawl fishing and its incidental catches in Buenaventura (Rueda and Escobar, 2017), where platoneras’ activities were identified as the most common within the trade link in both artisanal and industrial fishing. According to DANE (2019), the group of economic activities made up of fishing, hunting, mining, livestock, forestry, among others, represent 4.2% of the total employment in the district of Buenaventura. This is a considerable figure, bearing in mind that un- and self-employment amount to 20.3 and 51.8%, respectively (Cámara de Comercio de Buenaventura, 2020).

Despite of the above, there is no evidence of studies conducted on the platonera population where socioeconomic and gender aspects are addressed, thus allowing a more detailed understanding of the characteristics of women linked to these activities and their motivation for carrying them out. Therefore, this study aimed to collect socioeconomic information on the platoneras of Buenaventura and identify their contribution to the local economy and the fishing sector.

In addition, the limitations and gender gaps existing in the informality of the district’s local economy and the fishing sector in general were analyzed. The platoneras located in five key commercialization points within the district were characterized, identifying the main products commercialized while prioritizing five species and analyzing the value chain sensitive to gender and nutrition, based on the methodology designed by the FAO (2017, 2018), with an emphasis on peladas/corvina (Cynoscion spp.), specie of great importance in artisanal fishing in the Colombian Pacific (Correa-Helbrum et al., 2020). Finally, given the occurrence of the Covid-19 pandemic during the development of this study, information was collected to determine the lockdown’s impact on platoneras.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

The district of Buenaventura, located in the Colombian Pacific, belongs to the department of Valle del Cauca. It has 308,000 inhabitants, out of which 52.6% are women. This study focused on five market squares known locally as galerías, where the platoneras were identified: Plaza de la Independencia, Terminal Pesquero La Playita, Plazoleta Juan XXIII, Puente El Piñal, and Galería de Pueblo Nuevo (Figure 1).

Method

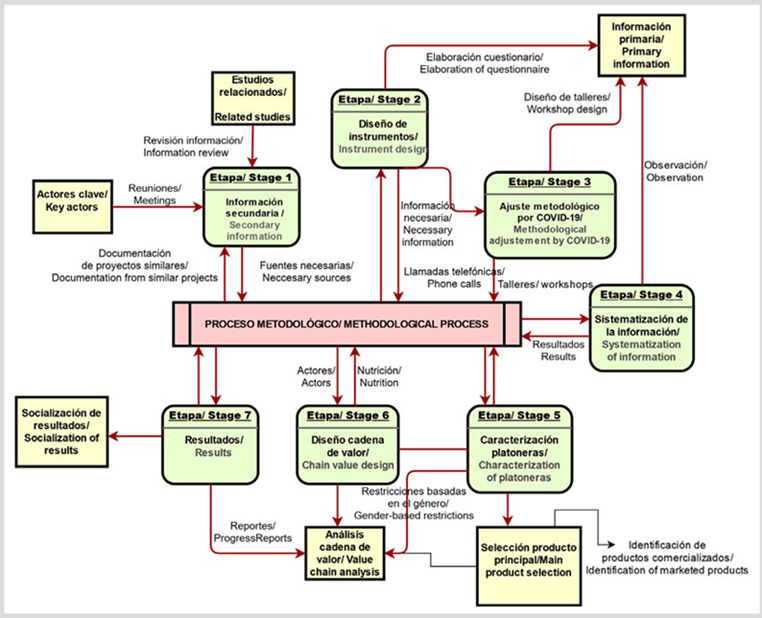

This study was conducted in seven stages (Figure 2). In the first one, a review of secondary information on studies conducted in the fishery sector at the national and local levels was carried out, aiming to understand more about this population and its key actors in the study area. The results obtained from analyzing the value chain of industrial shrimp fishing in the district of Buenaventura were analyzed (Barreto et al., 2022), where the activity of platoneras was identified as key within the trade link in both artisanal and industrial fishing -the total number of platoneras in Buenaventura may even reach 500. As a complement, according to a record obtained from AUNAP, as of February 2020, there were 141 platoneras distributed in five markets of the district. This population constituted the basis for determining the sample to be interviewed.

In the second stage, a qualitative participatory action methodology was designed and applied, where the observer constitutes a part of the universe to be investigated (Obando-Salazar, 2006). With this methodology, information on the social and economic characteristics of the women who perform platonera activities in the district of Buenaventura was obtained. This stage was carried out with the participation of a team of technicians and experts, who conducted field work and observation during the entirety of the process leading to the commercialization of fishery products, as well as reconnaissance in the commercialization points described by AUNAP. During March 2020, a total of 123 semi-structured interviews were carried out in five places where platoneras commercialize their products in Buenaventura: Plaza de la Independencia, Terminal Pesquero La Playita, Plazoleta Juan XXIII, Puente El Piñal, and Galería de Pueblo Nuevo. The survey consisted of 25 mixed questions (Table 1), classified by demographic and economic variables related to the activity and based on criteria for mapping value chains sensitive to gender and nutrition (FAO, 2017, 2018). The interview also included a table for recording commercialized products using three classification variables:

Profitability: a variable measured using the perceived product profitability as an indicator, that is, platoneras’ perception regarding the products that generate more income after they are sold.

Availability: this variable has been measured with an indicator of the frequency with which platoneras can access different species to later commercialize them.

Relevance in diets: this variable has been measured using two indicators: a self-consumption indicator, i.e., products that, in addition to being commercialized, are also destined for home consumption; and another organoleptic quality indicator, i.e., as perceived by the senses of those who consider these products to be nutritious, palatable, or with a good aroma or appearance.

Given that, since March 23, 2020, by means of Decree 457 of 2020 issued by the government, a sanitary emergency and lockdown were declared in the country due to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, this study included a new stage in its methodological development, which consisted of 22 phone calls to the previously interviewed platoneras who were identified as the leaders of each of the five commercialization points, with the purpose of inquiring about the impact of said lockdown on them and their economic activities, as a complement to the previously collected information. These answers were considered for the rest of the project activities, but they were not processed with the results obtained from the 123 interviews. The other instruments contemplated for collecting additional information, which included workshops and guides, were reformulated in order to adapt the methodologies to the new restrictions of mobility and assembly.

Design of a gender and nutrition sensitive value chain

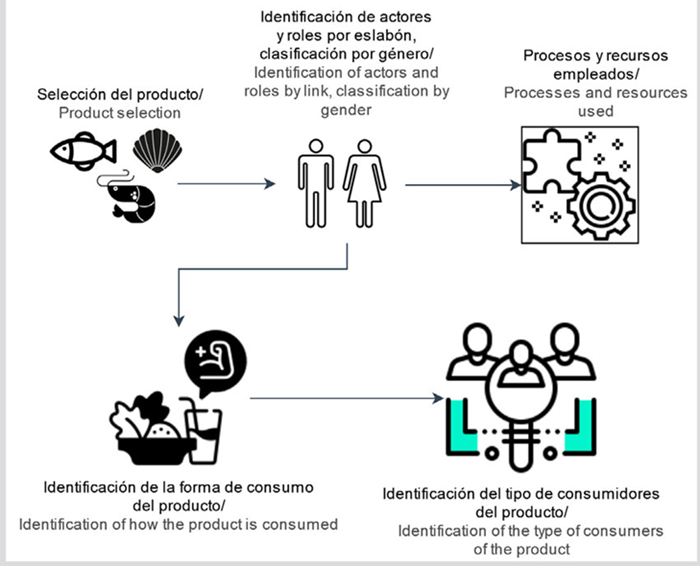

In the information systematization stage, and considering the results obtained regarding the products with the most commercial importance for platoneras based on their profitability, availability, and relevance in diets, the species pelada or corvina (Cynoscion spp.) was selected, as it had the highest score. Based on this result, the design of a gender- and nutrition-sensitive value chain began, which is different from traditional value chains because it analyzes the roles of men and women in each productive unit and addresses the determining factors underlying nutrition, such as food safety or a healthy food environment (FAO, 2017, 2018). Afterwards, based on the results obtained from the observation in the interviews, the actors intervening in the chain were mapped, establishing their roles (Figure 3). Then, the product selected for designing the chain was analyzed, determining whether it is subjected to different transformations from the first link until it reaches the final consumer, thus identifying which links are present in its chain (primary, secondary transformation), in addition to establishing the per-gender participation of the actors present in each of these links. The mapping also included the analysis of the product, it’s means of consumption, and the type of consumers.

The value chain analysis comprises the environment in which the product and the diverse actors interact, identifying the fishery product, its ecosystem, and its catch method, as well as the functions of the product and the chain in providing food to the different actors involved in it. Sociocultural, organizational, institutional, and infrastructure elements were also included (Figure 4), which, even though they are not regarded as direct actors in the chain, they do guarantee its development and play an important and determining role in its design and strengthening.

Figure 4 Gender- and nutrition-sensitive value chain elements identified in Buenaventura. Adapted from FAO (2018).

At a central level, the structure of the chain is related to the market since it concentrates in its links, such as catch, stockpiling, transformation, commercialization, and its role in the generation of supply and demand. At the same time, the chain identifies the roles played by the actors in its different links at both the individual and household levels, as well as regarding the access to the different services allowing to scale the chain, which includes services such as supplies and finances.

Then, an analysis was carried out regarding gender-based restrictions (RBG) at the individual and family levels, as well as within the value chain. The RBG analysis focused more on platoneras, considering the obstacles faced by women with respect to gender relations and the way in which the role they play in a specific value chain may remain hidden (Hill and Vigneri, 2011; FAO, 2013, 2014, 2018). For example, in the household context, the analysis was essential to understanding the social dynamics leading to restrictions, such as the lack of time or limitations related to accessing certain goods and services (FAO, 2018).

Based on this analysis, these RBGs were grouped into variables that allowed identifying their solutions. Finally, a risk analysis was conducted regarding food safety, which is included in the value chain based on the food system and the way it unfolds at the individual, household, and consumption levels, as well as according to each link in the central chain, taking the fishery product’s affordability, accessibility, and harmlessness as variables.

RESULTS

Characterization of platoneras in Buenaventura

The word platonera is used in the Colombian Pacific to refer to people who commercialize products on the street in plastic or metallic platones that rest upon their heads. Even though most platoneras currently have a permanent stand and do not carry these platones upon their heads, the word for these people is still in use, who mainly sell fishery products and fruits. This group is mostly made up by afro-descendent women; although there are also men who perform this activity, their participation is considerably low, amounting to only 5% of the interviewees. The average age of platoneras is 50 years old, and they engaged in the activity since they were 25 years old on average. As for the composition of their households, these tend to be constituted by four people, where two of them work and the others are dedicated to studying. Platoneras do not have a fixed salary or social services, but the 123 interviewees have access to healthcare. 94% of them have access to this service since they belong to the healthcare system’s subsidized regime, a mechanism defined by the State for the population that is most vulnerable or has a lower payment capacity to be able to access said services (Departamento Nacional de Planeación, 2022). The remaining 6% belong to the contributory regime.

Platoneras’ average income from this activity is COP $ 87,500 on a daily basis. This income is variable, as it depends on daily sales and the products available, with COP $ 12,000 being the minimum and COP $ 40,000 the most frequent income. The commercialization point with the lowest average income was Plazoleta de la Independencia, with COP $ 46,300, and highest one was reported at Terminal Pesquero La Playita, with COP $ 112,700. As for the most frequent income (mode), the highest incomes were reported by La Playita and El Piñal ($100,000 COP, Figure 5). For 93% of the people interviewed, this activity represents 100% of their income. Those who mentioned dedicating to another activity work at restaurants, in cellphone minutes sale, or in the transformation of fishery products.

Figure 5 Average income (bar) with its standard deviation and mode (circles) for the platoneras at each commercialization point in the district of Buenaventura.

Platoneras usually sell up to 60 products including 49 fish, mollusk, and crustacean species, as well as 11 subcategories based on the type of preparation (smoked), presentation (fillet), and type of fish (thick, small, as a function of size). Within the products commercialized, land mammals are highlighted: guaguas (Cuniculus paca) and armadillos (Dasypodidae); as well as a fruit: coconut (Cocos nucifera); and five main fishery products (Table 2).

It was identified that, overall, pelada (Cynoscion spp.) is the most important species with regard to the three prioritized variables, given its profitability, availability, and relevance in diets (Figure 6) followed by the snapper and the shark. As for the relevance in diets variable, the products that are commercialized on a daily basis are also used for home consumption, and the main reasons for that are taste, nutrition, and economy. Considering these results, the product selected for the value chain design was pelada.

Analysis of the pelada (Cynoscion spp) value chain

The links identified in this chain were catches, stockpiling, transformation, and commercialization (Figure 7). Within catches, there are primary extraction activities involving artisanal and industrial fishing and vessel and fishing gear preparation. This link is predominantly masculine, with 2% of women participation in the fishing gear repair activity.

The activities identified in the stockpiling link are the separation of the landed catches and product cleanup, packaging, and transportation. There is a similar participation of women and men in this link. However, there is indeed a clear differentiation in the activities performed. For example, regarding catch landing, 98% of the people identified were men. As for the other activities in this link, such as fish arrangement, preparation, and sale, these are mostly performed by women (90%).

Pelada is a product that is commercialized fresh; it does not undergo transformation or elaborate or industrial processing along its chain. As processes, cleanup, peeling, evisceration, and cutting can be included. These processes are carried out by both artisanal or industrial fishermen and salespeople as an added value to their sales service, as requested by the buyer. Pelada is part of the target catch of industrial white seine fishing, as well as of the incidental catches of shrimp trawl fishing in shallow waters. In the same way, it was recorded as part of the artisanal catches with gillnets in wind and tide boats, as well as in the so-called ruches or gillnets used as a fence. Several species of the family Sciaenidae are utilized, with white pelada being one of the most abundant (Cynoscion phoxocephalus).

It was identified that pelada is part of the local diet, which is why its consumption is frequent in different traditional preparations (sudados and tapaos). The distribution and sales of the product are carried out from pesqueras (local fish shops) to restaurants and hotels. In the market squares where the platoneras are located, this product is mainly sold for consumption by local families.

Pelada undergoes minimal transformation processes from catch to consumtpion, which include evisceration, peeling, and cutting, which is why little waste is generated. The behavior of pelada along the chain indicates that there is an availability of the product for each of the actors. However, in the first link (catch), this product is little affordable, since the fishermen who catch pelada would rather sell it and consume other species with lower commercial value. Access is difficult for some sectors of the district, where the product is not commercialized due to issues related to insecurity and public order, as expressed by the interviewees.

The harmlessness of the product is maintained thanks to the cold chain implemented from the catch until it is delivered to the consumer. No chemicals or additives are employed, which is why the product’s useful life may be affected is this chain is broken. Platoneras have received training in food handling, with the purpose of ensuring that the product reaches the consumer in optimal conditions, and they have benefited from both the commercialization and consumption of this product.

Among the services identified along the chain is the sale of inputs, which is mainly present in the stockpiling and commercialization links. These are mainly offered in the neighborhood of Pueblo Nuevo, where pesqueras, restaurants, and a market square converge. Platoneras commercialize their products both within and in the streets adjacent to the latter. Financial services to support the commercialization of the product are provided by banks and informal lenders. For the remaining services, such as training, recordkeeping, and promotion of the activity, the actors identified were the Buenaventura Town Hall, the National Aquaculture and Fishing Authority (AUNAP), the National Learning Service (SENA), and the National Institute for Food and Medicine Monitoring (Invima).

Gender analysis of the value chain

This chain shows a clear gender role division (Figure 8), and, in the case of women, most of their participation takes place within the stockpiling, commercialization, and transformation links, which includes fish evisceration and cleanup, as well as product preparation and delivery in restaurants, where women cooks and waitresses intervene. As for the consumption link, women also play a predominant role, given that platoneras consume the product they sell and take it home, but women cooks and kitchen assistants also acquire the product (with even greater frequency). In addition, housewives or heads of household handle the selection and acquisition of products to feed their families.

Even though they play other roles, platoneras stand out in commercialization, as they are in charge of distributing the product across the district. Among the reasons to carry out this activity is the fact that it is traditionally “made for women”, as mentioned by one of the interviewees. This is due to the characteristics believed to be typical of women, such as being careful with the product, good customer service, order, and better handling of the food.

The gender-based restrictions (RBG) identified at the individual level were the low education level of the women in this chain and extensive work shifts with no resting hours. The latter is due to the fact that their role as platoneras implies a workload between 7 and 14 hours a day, as their work begins before 6:00, when they approach the landing points of artisanal fishermen -their main suppliers- in order to acquire the product to be distributed at their selling points. The commercialization activity ends at 17:00 or 18:00. These work shifts take place from Monday to Sunday for 77% of the interviewees. They dedicate rest of the day to unpaid care activities in their household. Platoneras believe that this activity is an opportunity for them to perform a task independently, which does not require much preparation or a high education level, thus evidencing restrictions at the social level, since job opportunities in the district for female heads of household without an academic background are quite reduced.

The work carried out by platoneras allows women to autonomously manage their income, as they are the ones who receive the activity’s daily income and utilize it to fund their work, to acquire fresh products for commercialization, and to meet their household’s needs. However, access to the necessary resources for fishing activities (which are also present in the different links of the chain) does pose a series of restrictions. This, because the fact that they belong to men, who mostly carry out catch activities and decide on its use for themselves. Major restrictions encompass sociocultural, organizational, institutional, and infrastructure elements, as well as the access to services and resources identified as necessary for the activity, which exhibit a gender-based restriction and constitute a bottleneck for the link that requires said resources, as well as for its actors. A major restriction for women, which was identified in the vessels, is cultural in nature, as there is a belief that women do not bring good luck to the boat, which is why men do not allow them to come aboard to go fishing. As for the labor capital resource, a restriction for both men and women has to do with informality, since it does not allow them to easily gain access to credit lines. This, due to their daily and variable income, which is why informal credit is employed as labor capital (Table 4).

Informal work and Covid-19

The work conditions of fishing stakeholders are not optimal. Platoneras do not have any additional income that protects them in the face of disability or during maternity, nor do they have access to a pension for their old age, which is why it is common to find platoneras older than 70 who still perform these tasks. Due to the informality present in fishing activities, the access to credit becomes difficult, thus generating aversion to it and limiting the possibilities of acquiring or improving labor capital. 34% of the interviewees has never requested or acquired credit, stating that they do not like debt and are afraid of not being able to pay the loan, or that their request has simply been denied. Another 30% of the platoneras stated that they have acquired credit with informal lenders, which, even though they charge a daily interest rate, allows them to acquire the product to be commercialized on the next day.

Moreover, there are no saving mechanisms within the activity that allow having an emergency fund in the face of some calamity or an abrupt stop, as it happened with the mandatory preventive lockdown decreed by the national government as a measure to avoid infections caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Although this study did not intend to analyze the impact of an extraordinary situation such as the declared pandemic on the platoneras’ work, it is important to consider that this situation generated a restriction to the exercise of their profession, and therefore to this group’s socioeconomic conditions. According to Buenaventura’s Chamber of Commerce (Cámara de Comercio de Buenaventura, 2020), between March 26 and April 30, 2020, the district experienced a 100% reduction in the generation of indirect employment, as well as a 50% decrease in direct employment. The fishing sector’s operation operated at 10% capacity, thus affecting 70% of direct jobs and 85% of indirect ones. Its sales dropped by 90%.

DISCUSSION

It is important to acknowledge the role played for decades in fishing activities by platoneras in Buenaventura, given that, as evidenced in the value chain, they actively contribute to the economic dynamics of fishery products. They work as stockpilers by receiving products from artisanal fishing, and they are the main sellers of the catches made by artisanal fishing and, to a lesser extent, by industrial fishing across the district and among the low-income population. Platoneras contribute to the local economy’s dynamism and generate income for themselves and their families, even though their participation in these activities is due to cultural factors such as the association of this labor to the female gender, as well as to poverty and a lack of opportunities (Ihalainen et al., 2020). Although commercialization activities in fishing have a high female participation, there are cultural barriers limiting women’s performance in other roles such as fishing, which is why the women who exercise this labor may spend more time inland than their male counterparts (Bradford and Katikiro, 2019).

Women’s contribution to fishing requires new measurement methods, as there is a gender bias in research and the data minimize their role in fishing (Kleiber et al., 2015). Some studies have calculated women’s contribution in the chain’s catch link as a function of the amount of product that it represents, but these contributions should be measured in terms of feeding, nutrition, and poverty relief (Harper et al., 2020).

Gender and nutrition sensitive value chain

The pelada value chain shows activities with a high degree of informality along its links, with no gender distinction. The first link (catch) is mostly represented by men, fishermen who receive an income for their labor, although they mostly do not have formal employment or social assistance. However, designing a gender-sensitive value chain has allowed for the identification of both the different roles present in the links and their gender-based work division, which has significant implications for the way in which men and women may dedicate their time to paid and unpaid work, education, medical assistance, social media, leisure, and other activities (Kruijssen et al., 2018).

On the other hand, the value chain’s focus on nutrition provides a practical way to address the complexity of food systems and identify entry points (in terms of policies and investment) to ensure that the systems contribute to improving food safety and nutrition in a sustainable way (Comité de Seguridad Alimentaria Mundial, 2016). Pelada’s contribution to nutrition is based on the fact that it is a food present in local diets by tradition, it generates income along the chain, and contributes to the community’s food safety, as well as that of platoneras and their families, given that it is also a product for self-consumption. Thus, the platonera tradition goes hand in hand with the local gastronomic tradition, which is clearly derived from cultural encounters with peoples of African origin, indigenous peoples, and Hispanic colonizers (Ministerio de Cultura, 2017). It is evidenced that platoneras are autonomous with regard to their economic resources, which they receive on a daily basis and grant them decision-making power on the use of these resources both for their activities and in the household’s finances. However, the use of these resources is focused on continuing with the activity, as they buy the product to be sold on the next day with the income received from sales on the day before, and they resort to informal loans when they cannot maintain the activity. Even though this is a paid activity, the scarce free time they have after working as platoneras is dedicated to unpaid care.

This study provided information to the discussion about women’s contribution in fishing activities, including variables that allowed differentiating the gender roles taking place along the value chain of a traditional and relevant product of the Colombian Pacific’s gastronomy, as is the case of pelada. This resource constitutes a potential offer for platoneras, as it is the target catch of artisanal gillnet fishing, with an exploitation state that does not threaten the species’ sustainability. In the same way, in 2020, pelada amounted to 36% of industrial catches with seine nets, and it is part of a varied percentage of incidental catches made by shrimp trawl fishing, whose offer of incidental catches and discards oscillated between 500 and 6000 ton, with 2583 ton on average between 2008 and 2019 (Rueda and Escobar, 2017; Rueda et al., 2021).

Overcoming the RBGs

Regarding limited access to financial services, scarce participation and leadership, and extensive work shifts as major restrictions, mechanisms are proposed which allow overcoming the gender-based restrictions identified along the chain. These include designing gender-sensitive financial products allowing women to gain access to formal credits, as well as with the possibility of collective savings among the different associations identified. This means greater involvement in the activities and programs carried out in the district, thus allowing for greater inclusion and feedback for the design of public policies, as well as a strengthening of the women’s associations already established along the value chain. Finally, improvements to the products’ commercialization points should be made which allow for a better handling of the cold chain and longer conservation times, thus contributing to reduce work shifts.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Information gaps with regard to this chain and the real number of platoneras working in the district of Buenaventura have not allowed conducting a deeper analysis of the value chain. A study with a greater scope which allows to quantify the total number of platoneras in both fixed and moving stands would be of great relevance and may contribute to making this labor more visible and including it in the fishing sector’s agenda, thus generating opportunities for improvement with respect to work conditions, the structure and installed capacity of the commercialization points, and maintaining generational change in these activities, with better conditions than those of older platoneras.

It is recommended that future studies address gender variables in order to more accurately understand the contribution made by women to this activity regarding both paid and unpaid labor. It is also necessary for policies and regulations with regard to pelada to be in line with this resource’s relevance in platoneras’ tradition and economy. This, accompanied by studies that determine the impact of this product and the platoneras who sell it on food safety and the district.

On the other hand, addressing social protection aspects for this group in particular and for fishing in general will allow to determine the gaps that limit their access and affect the quality of life of the fishing stakeholders in the case of closures, as it happened during the declared pandemic in 2020.

text in

text in