INTRODUCTION

There is little knowledge of the biodiversity of sponges (phylum Porifera) inhabiting mesophotic areas (30 to 150 m) in the Colombian Caribbean, given that, in addition to the limited access to these environments, their identification is a complex task due to the ambiguity of their morphological features, as the literature is still disperse (Hooper and van Soest , 2002). However, these limitations have begun to dissipate thanks to submarine photography, the rise of integrative taxonomy (by means of incorporating molecular techniques into morphological analyses), more detailed field observations, and the increase in explorations and studies focused on characterizing the fauna associated with the continental shelf (Zea and Weil, 2003; Díaz and Zea, 2008; Xavier et al., 2010; Zea et al., 2014; Zea and Pulido, 2016; Silva and Zea,2017).

On soft bottom areas, sponge communities are less diverse than those inhabiting shallow, hard substrates in littoral ecosystems, which is partially due to homogenous relief, sediment instability, and the low availability of a firm substrate to support them (Pansini and Musso, 1991; Ilan and Abelson, 1995; Valderrama and Zea, 2013). It is believed that there are two substrate components that allow for sponge settlement: sand and mud for species with anchoring habits; and gravel, mollusk shells, and crustacean exoskeletons for those that require a means of adhering to the substrate (van Soest, 1993; Rützler 1997). This, unlike rocky bottoms with heterogenous relief and more substrate stability, limits the presence of a large number of sponge species (Parra-Velandia and Zea, 2003).

In Colombia, sponge studies have focused on the class Demospongiae, which is partially due to the fact that it represents nearly 90% of the total species known, with an estimated 350 species between 0 and 50 m deep (Zea, 1998; Silva and Zea, 2017), however, there are also a few reports of three species and a complex of species of the Homoscleromorpha class down to 50 m (Wintermann-Kilian and Kilian, 1984; Zea, 1987; Valderrama, 2001; Díaz and Zea, 2008; Zea and Díaz-Sánchez, 2011; Valderrama and Zea, 2013). In general, research on this phylum have focused on identifying the species present in rocky littorals and coral reefs, which has been conducted mainly in the following areas: Santa Marta, Urabá, and San Andrés and Providencia (Zea and Rützler, 1983; Zea, 1987, 2001); Urabá-Capurganá (Valderrama and Zea, 2003, 2013); Cartagena, Rosario and San Bernardo Archipelago (Zea and Díaz-Sánchez, 2011; Díaz-Sánchez and Zea, 2016); La Guajira (Díaz and Zea, 2008, 2014; García et al., 2013); and the Seaflower Biosphere Reserve (Abril-Howart et al., 2011; Díaz-Sánchez et al., 2013). This highlights the necessity of conducting research that focuses on mesophotic ecosystems. The sponge collection of the Museum of Marine Natural History of Colombia (MHNMC) was created in 1982 and currently has 2.498 lots. Only 38% of the material has been identified at the species level, with specimens collected both in the Caribbean and the Colombian Pacific. It is one of the few collections in the country that keeps sponge specimens, which is why, in addition to the great relevance of the group in taxonomic, ecological, medical, commercial, and pharmaceutical terms, it is important to conduct systematic studies based on already existing data and biological material, in order to not only strengthen the knowledge about the group, but also to make this type of biological collections and their importance known, as well as to promote their use and research.

In this context, this study aims to increase the knowledge of the sponges present in the continental shelf of the south-western area of Isla Fuerte and Alta Guajira in the form of a systematic list of species that collects unprocessed information of the MHNMC, via the curation, updating, taxonomic identification, and generation of new knowledge regarding sponges in the Colombian Caribbean.

STUDY AREA

This study was carried out in two hydrocarbon exploration regions located in the Colombian Caribbean. The first zone in the northeastern region of the Guajira Peninsula, stretching from Manaure to the vicinity of Punta Espada. This area experiences upwelling for most of the year, resulting in oxygenated, colder, saltier, and nutrient-richer waters as compared to other sectors of the Caribbean (Corredor, 1979; Fajardo, 1979; Álvarez-León et al., 1995; Andrade and Barton, 2005). The seabed here consists of muddy and coarse sand bottoms, with geological formations associated with the sedimentation processes of the Magdalena River delta (Shepard et al., 1968; Shepard, 1973; Invemar-ANH, 2008).

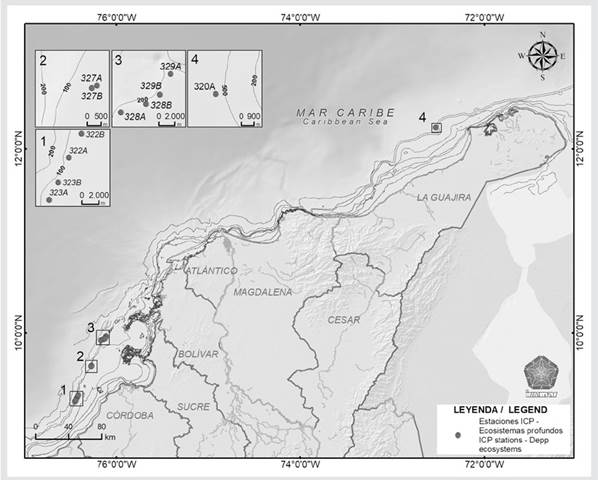

The second area is located in the southwestern region, spanning from Puerto Rey cove in the Antioquia department to the front of Los Morros township in the north of the city of Cartagena, in the Bolívar department (Figure 1). This region is influenced by the runoff from the Sinú and San Jorge Rivers and has a flat and homogenous bottom with muddy and clayey sediments (Invemar-ANH, 2008).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between November 23, 2011, and August 6, 2012, researchers of the José Benito Vives de Andréis Institute for Marine and Coastal Research (Invemar) evaluated the distribution and composition of the organisms associated with deep sea coral. They carried out three research campaigns in hydrocarbon blocks that had been analyzed under previously established parameters, such as the probability of coral presence, the geoforms of the seabed, depth, and previous evidence of stations where structuring coral species had appeared, managing to establish 16 stations, out of which only 11 were taken (Table 1) due to the presence of sponges.

Table 1 Sampling stations in the continental shelf of Isla Fuerte and Alta Guajira, Colombian Caribbean.

Based on the previously conducted reconnaissance, the researchers used linear 1 km trawls with semi-balloon nets for 10 minutes. They filtered, washed, and separated the samples depending on the taxonomic group, where the sponges were fixed in formol at 4% and separated by morphotypes for later labeling and storage in the Museum of Marine Natural History of Colombia (MHNMC) (Figure 2).

In the sponge collection of the MHNMC, diagnostic activities, historic information collection, general curation, and the separation of 224 lots were carried out. On the latter, permanent assemblies of clean spicules and skeletons were performed, as described in Zea (1987). They were observed and photographed using an optical microscope (Zeiss, Axio Lab. A1). Up to 25 spicules of each class were measured, as well as the most relevant skeletons structures of the specimens identified as new records for the Colombian Caribbean. The measurements are presented as the minimum-average-maximum length x width in μm. Identification was carried out by consulting the keys of the Systema Porifera (Hooper and van Soest, 2002) and the descriptions of the material from the Colombian Caribbean and the Caribbean and Atlantic oceans in general, with the help of the species lists of the World Porifera Database (http://www.marinespecies.org/porifera). Regarding synonymy, only the information of the World Porifera Database was used. The studied material was stored in the sponge collection (INV POR) of Invemar’S Museum of Marine Natural History of Colombia (MHNMC), while the information was entered in the database of the Colombian Marine Biodiversity Information System (SIBM) and the Ocean Biodiversity Information System (OBIS) and Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) global information systems.

RESULTS

In total, 89 taxa were identified which belong to the classes Demospongiae and Homoscleromorpha, which were grouped in 16 orders, 33 families, 51 genera, and 45 species, out of which 10 are new records for the Colombian Caribbean**. Table 2 presents the list of identified species.

Table 2 List of sponge species grouped by depth (73 to 210 m). Bold letters indicate new records for the Colombian Caribbean.

New records for the Colombian Caribbean

Class Demospongiae Sollas, 1885

Order Haplosclerida Topsent, 1928

Family Chalinidae Gray, 1867

Genus Haliclona Grant, 1841

Subgenus Reniera Schmidt, 1862

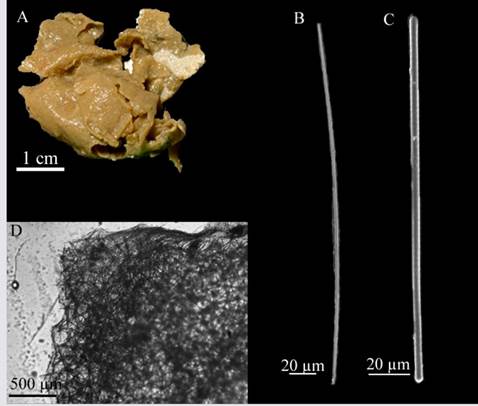

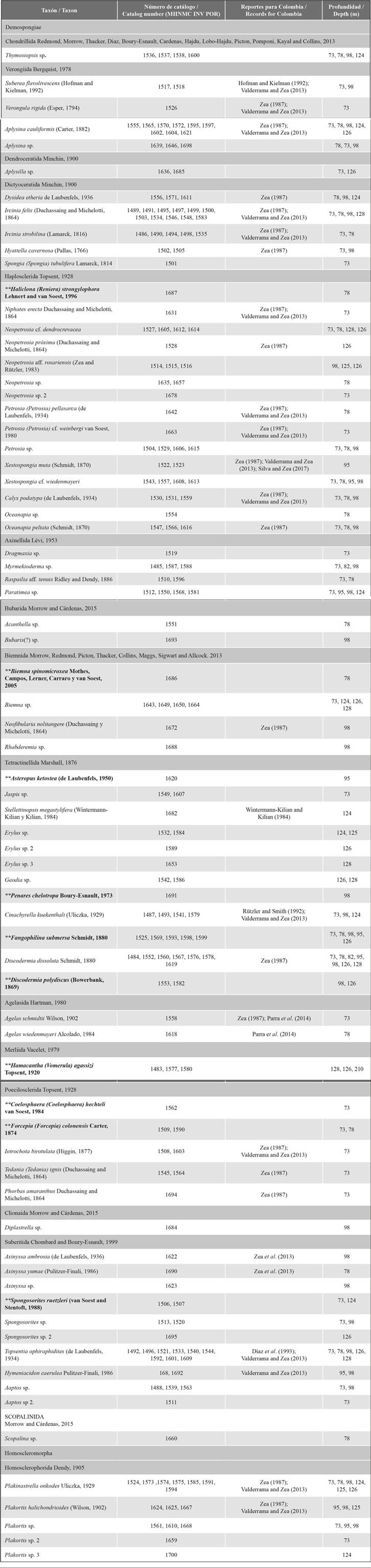

Haliclona (Reniera) strongylophoraLehnert and van Soest, 1996 (Figure 3 A - D)

Haliclona strongylophoraLehnert and van Soest, 1996: 73, figs 12, 25, 73.

Studied material: INV POR1687, Isla Fuerte, 78 m, col. Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-07-30.

Description: amorphous, soft, brittle sponge 5 × 3 cm in diameter, approximately 0.3 cm thick, flat surface, no visible oscula, beige-colored in alcohol (Figure 3A). Skeleton: Ectosome: irregular reticulation of individual spicules and a considerable amount of sediment; choanosome: isotropic reticulation of four to six 41.5 - 27.0 - 14.5 µm spicules, with a mesh diameter of 129.3 - 87.1 - 44.5 µm (Figure 3D). Spicules: strongyles, 185.5 - 172.5 - 154.9 µm long × 6.7 - 5.1- 3.2 µm wide (Figure 3C), some of them in development stages, thinner and with conic or telescopic ends and, in some cases irregular swelling (Figure 3B).

Habitat: soft bottoms in mesophotic environments.

Distribution in the Caribbean: Discovery Bay, Jamaica (Lehnert and van Soest, 1996), Colombian Caribbean.

Comments: This species differs from all other Halicona species described for the Caribbean (van Soest, 1980; De Weerdt et al., 1991), since they have strongyles as the only type of spicule, as described by Lehnert and van Soest, 1996. Haliclona (Soestella) brassica Bispo and Pinheiro, 2014 has strongyles but also presents raphides in rare trichodragmata. Haliclona (Reniera) implexiformis (Hechtel, 1965), H. (Re.) tubifera (George and Wilson, 1919), H. (S.) caerulea (Hechtel, 1965) and H. (Halichoclona) albifragilis (Hechtel, 1965) possess oxeas with strongyloid modifications, but they never have strongyles exclusively.

Order Biemnida Morrow, 2013

Family Biemnidae Hentschel, 1923

Genus Biemna, con su autor y fecha

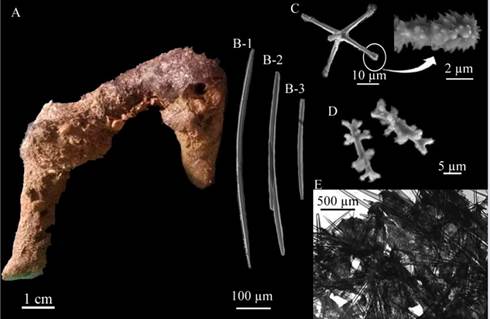

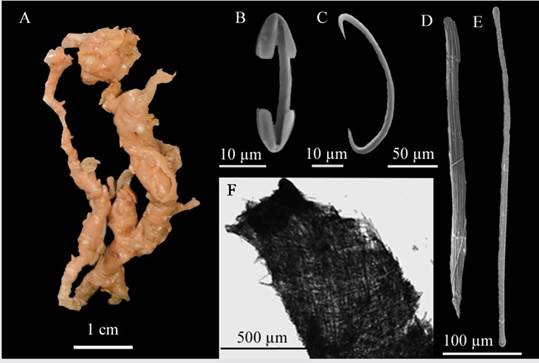

Biemna spinomicroxeaMothes, Campos, Lerner, Carraro, and van Soest, 2005 (Figure 4 A-E)

Biemna spinomicroxeaMothes et al., 2005: 41-42, fig 2; Muricy et al., 2011: 151.

Studied material: INV POR1686, Isla Fuerte, 78 m, col. Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-07-30.

Description: massive, irregular sponge, internally cavernous, dimensions: 6 cm wide × 4.5 cm long, corrugated surface, oscula 0.2 cm in diameter spread across the surface, soft consistency, easily compressed and crumbled, light brown-colored in alcohol (Figure 4A). Skeleton: no distinction can be made between ectosome and choanosome. Ascending irregular tracts 245.5 - 149.4 - 72.2 µm thick, composed of three to five spicules connected by transversal tracts with some randomly distributed microscleres (Figure 4E). Spicules: megascleres: slightly curved oxeas, slightly phased limbs, some of them slightly strongylated 412.8 - 363.2 - 311 µm long × 17.5 - 12.3 - 17.5 µm wide (Figure 4B); Trichodragmas: 160.7 - 145.5 - 131.4 µm long × 6.1 - 4.5 - 16.5 µm wide (Figure 4C). Microscleres: sigmas of shallow curves with thorny ends, 20.6 - 17.2 - 14 µm long (Figure 4D).

Habitat: soft bottoms in mesophotic environments.

Distribution in the Caribbean: Amapá, Brazil (Mothes et al., 2005); Colombian Caribbean.

Comments: considering the description made by Mothes et al. (2005), this specimen has raphides enclosed in trichodragmas instead of oxeas. However, unlike the Biemna species described for the tropical Atlantic, like Biemna cribaria (Alcolado and Gotera, 1986) among other, megasclere spicules are oxeas and microsclera spicules do not have two sigma categories and do have spiny tips, which is why it was assigned to the species Biemna spinomicroxea.

Order Tetractinellida Marshall, 1876

Family Ancorinidae Schmidt, 1870

Genus Asteropus, su autor y fecha

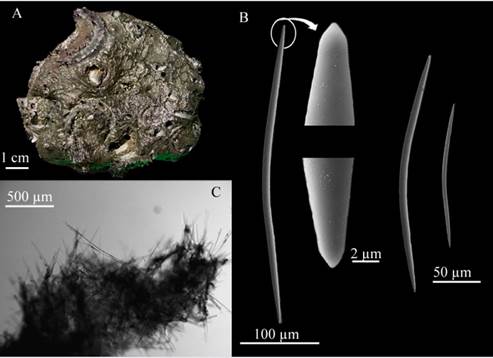

Asteropus ketostea (deLaubenfels, 1950) (Figure 5 A-E)

Stellettinopsis ketostea de Laubenfels, 1950: 112 - 114, text-fig. 50 A - D; 1954: 224.

Asteropus ketostea;Bergquist, 1965: 189 (genus change); Hajdu and van Soest, 1992: 8 - 9. Desqueyroux-Faúndez(?), 1990: 378, figs. 13 - 15; Rützler et al., 2009: 295 (lista).

Studied material: INV POR1620, Isla Fuerte, 73 m, col. Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-08-02; INV POR1675, Isla Fuerte, 95 m, col. Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-07-29.

Description: massive, irregular lobed sponge, 12.6 cm long × 2.1 cm wide, hard consistency, little compressible, hispid surface with abundant pores, nut no evidence of oscula, dark purple on the surface and gray coloration in alcohol (Figure 5A). Skeleton: Ectosome: composed of large amounts of selenaster microscleres interleaved with paratangential oxeas; Choanosome: with large oxeas forming irregular tracts of large, 385.2 - 209 - 79.5 µm wide oxeas and some smaller, thinner, and randomly dispersed oxeas (Figure 5E); Spicules: Megascleres: three oxea categories: oxea I: spindle-shaped, large, slightly curved, with gradually narrow tips, 2515.2 - 1846 - 1147.5 µm long × 76.4 - 51.3 - 33.2 µm wide (Figure 5B-1.); oxea II: thin, spindle-shaped, slightly curved, with gradually narrow tips, 1371.6 - 883 - 553.2 µm long × 36.5 - 23 - 11.6 µm wide (Figure 65B-2.); oxea III: thin, spindle-shaped, slightly curved, 316.2 - 526.4 - 661.3 µm long × 3.5 - 1.0 - 1.5 µm wide (Figure 5B-3.); Microscleres: sanidasters with more than 10 micro-spined rays, bifurcated or not, distributed along the 22 - 17.7 - 13.8 µm long axis (Figure 5D.); oxiasters (n=17): thin, with four to six micro-spined radii at the tip of each radius, 66.5 - 50.9 - 43.1 µm long (Figure 5C).

Habitat: soft bottoms in caves of shallow and mesophotic environments.

Distribution in the Caribbean: Bermuda (de Laubenfels,1950), Gulf of Mexico (Rützler et al., 2009); Colombian Caribbean.

Comments: so far, for the Colombian Caribbean, not many species have been recorded which exhibit a combination between oxea megascleres and oxiaster and selenaster microscleres, which is why the original description by de Laubenfeld (1950) was consulted, i.e., “Stellettinopsis ketostea”. This description matched this spicule combination although there is a significant difference in oxeas and sanidasters size (Oxea I: 1000 µm long × 25 µm wide; Oxea II: 800 - 600 µm long × 15 - 8 µm wide; Oxea III: 400 µm long ×3 µm wide and Sanidaster: 12 - 18 µm long), there are no subsequent characterizations of this species The record made by Desqueyroux-Faúndez (1990) in Easter Island should be verified, as it is from another ocean.

Family Geodiidae Gray, 1867

Subfamily Erylinae Sollas, 1888

Genus Penares, autor, año

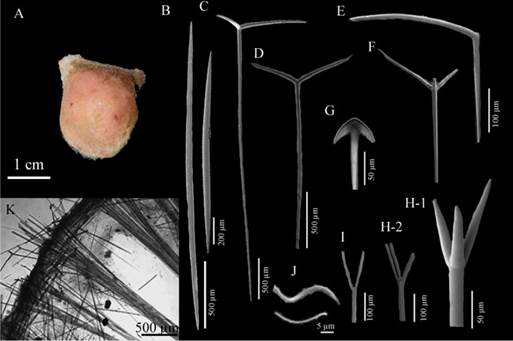

Penares chelotropaBoury-Esnault, 1973 (Figure 6 A - G)

Penares chelotropaBoury-Esnault, 1973: 271-272, fig 10: Hechtel, G.J., 1976: 253; Muricy et al., 2011: 41; van Soest, 2017: 90 - 91, fig 56.

Studied material: INV POR1691, Isla Fuerte, 98 m, col. Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-07-29.

Description: sponge with elongated and flat lobes, measuring 3 to 5.2 cm in length and 0.5 cm in diameter. It features a mildly corrugated surface, firm consistency, and exhibits a brown to ochre-colored when in alcohol (Figure 6A). Skeleton: Ectosome: composed of one dense micro-oxea scab with a thickness of 310.7 - 183.6 - 59.7 µm wide (Figure 6F) supported by the cladomes of orthotriaene megascleres on the surface. The scab has little round perforations with a diameter of 90.6 - 53.2 - 37.8 µm, separated from each other by 296 - 204 - 134.8 µm (Figure 6G). Spicules: Megascleres: two oxeas categories, oxea I: long and spindle-shaped, slightly bent, 702.2 - 573.3 - 467 µm long × 18.3 - 11.7 - 7.2 µm wide (Figure 7C-3.), oxea II: short, spindle-shaped, slightly bent, 197 - 160.8 - 127 µm long × 12.3 - 8.6 - 5.8 µm wide (Figure 6C-1, 2.). Orthotriaenes (n=17): similar to caltrops in shape, given that the rhabdus and clade have approximately equivalent lengths, but they differ from each other because rhabdes are straight and clades generally have curved or sometimes slightly twisted ends; Rhabdomes: 473.3 - 370.4 - 140.6 µm long × 14.3 - 10.3 - 7.2 µm wide; Cladome: 287.4 - 226.3 - 79.2 µm long × 14.3 - 10 - 7.2 µm wide; Clade: 401.2 - 292 - 108.3 µm long × 11.7 - 9.7 - 108.3 µm wide (Figure 6B-1,2). Microscleres: curved, pointy micro-oxeas with the shape of an oxea, but occasionally with a swollen central part, 96.2 - 61.2 - 35.6 µm long × 4.2 - 3 - 1.7 µm wide (Figure 6E), oxiasters with micro-spined tips, 7 - 8 radii 24.3 - 17 - 11.4. µm in diameter (Figure 6D).

Figure 6 Penares chelotropa. A. Fragment, B-1,2. Orthotriaenes, C-1. Oxea II, C-2. Oxea I, D. Oxiaster. E. Micro-oxea, F. Choanosome, G. Ectosome.

Habitat: soft bottom in mesophotic environments.

Distribution in the Caribbean: Guyana continental shelf (van Soest, 2017), north-eastern Brazil (Muricy et al., 2011); Isla Fuerte, Colombian Caribbean.

Comments: the spicule shape and details of the specimens closely resemble those of the P. chelotropa holotype, hence the identification is confidently established. Boury-Esnault (1973): 272), names tilaster-type asters, but the ends of the spicules are pointy under SEM, so they are identified as oxiasters.

Family Tetillidae Sollas, 1886

Genus Fangophilina y de su autor y fecha

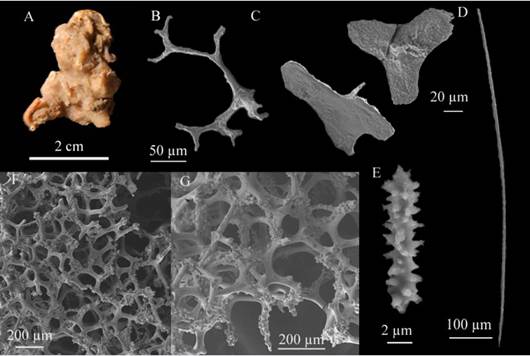

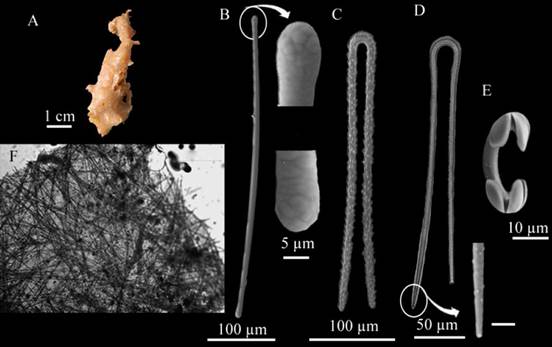

Fangophilina submersaSchmidt, 1880 (Figure 7 A - K)

Fangophilina submersaSchmidt, 1880: 73-74, plate X, fig 3; Topsent, 1923: 2 (redescription, fidede Voogd, 2022a); van Soest, 2017: 112, 69.

No Fangophilina submersa; Pulitzer-Finali, 1993: 261; Burton, 1956: 122-123; Burton, 1959: 201 (fidede Voogd et al., 2022a).

Studied material: INV POR1525, Isla Fuerte, 73 m, col. Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-07-29; INV POR1569, Isla Fuerte, 98 m, col. Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-08-03; INV POR1593, Isla Fuerte, 78 m, col. Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-07-30; INV POR1598, Isla Fuerte, 126 m, 2012-08-05. INV POR1599, Isla Fuerte, 95 m. col. Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-08-02; INV POR1628, Isla Fuerte, 78 m, col. Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-07-29; INV POR1666, Isla Fuerte, 82 m. col. Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-07-28.

Description: Globular sponge with two very prominent hispid lateral porochalices approximately 1.5 cm in diameter and 2 cm in height, with an average size between 1 and 3 cm in diameter, the surface looks flat but is micro-hispid to the touch, somewhat compressible consistency, light beige-colored in alcohol, sometimes light pink (possible presence of dye during fixation) (Figure 7A). Skeleton: Ectosome: spicule tracts strongly radiating from the porochalices to the center of the sponge’s body, prodiaene spicules forming a layer on the surface and randomly distributed sigmaspire microscleres; Choanosome: thin tracts composed of long megascleres: oxeas protruding from the ectosome, plagiomono-, di-, and triaenes, anatriaenes, prodi- triaenes (Figure 7K.). Spicules: Megascleres: distinguishable oxeas in two size categories, oxea I: long, with pointy ends, 2923 - 1742.4 - 1155.7 µm long × 41.1 - 24.5 - 12 µm wide (Figure 7B-1.), oxea II: slightly shorter, with pointy ends, 1108 - 762.6 - 461.5 µm long × 31 - 17.2 - 11.6 µm wide (Figure 7B-2); Orthomonoenes: straight clade shaped like a scythe, 602.5 - 399.2 - 199.1 µm long × 22.1 - 16.5 - 8.7 µm wide, straight rhabdome, some of them sinuous, 2718 - 1946.4 - 1469 µm long × 25 - 18.7 - 12 µm wide (Figure 7E.); Orthotriaenes: large, with diaene conditions, 2325.5 - 1667.2 - 948.3 µm long × 19.3 - 10 - 4.1 µm wide rhabdomes, 812.7 - 434.5 - 201 µm long cladome, 400.5 - 247 - 106.5 µm long × 14.2 - 9.7 - 6 µm wide clade (Figure 7C.); Plagiodiaenes: 2770.7 - 1531.4 - 870.1 µm long × 26.3 - 17.7 - 8.7 µm wide rhabdomes, 571.3 - 359 - 162.1 µm long cladome, 327.6 - 228 - 87.4 µm long × 22.1 - 14 - 5.8 µm wide clade (Figure 7D.); Plagiotriaenes (n=15): rhabdome, sometimes bent, 2624.7 - 1763.7 - 1181.5 µm long × 31 - 16.7 - 9.2 µm wide, 436.7 - 330.7 - 226 µm long cladome, 259.7 - 188.7 - 116.4 µm long × 22.1 - 13.7 - 6.5 µm wide clade (Figure 8F.); prodiaenes in two distinct size categories (I, n=15): robust, with thick, almost parallel clades, 2727.6 - 1469.3 - 1185 µm long × 38.2 - 25 - 12 µm wide rhabdome, 259 - 153 - 95 µm long cladome, 259 - 161.5 - 79.4 µm long × 35 - 22.6 - 13 µm wide clade; prodiaenes II (n=9): thinner and smaller, with very long and thin clades, 1596 - 1263.4 - 655.2 µm long × 6.2 - 3.7 - 1.8 µm wide rhabdomes, 82 - 51 - 34 µm long cladome, 97.8 - 69.3 - 28.1 µm long × 4 - 3.1 - 2.1 µm wide clade (Figure 7I.); protriaenes in two distinct size categories, protriaenes I: robust, with thick, almost parallel clade, 3128.6 - 2459 - 1379.5 µm long × 23.6 - 13.8 - 5.2 µm wide rhabdome, 218.6 - 140.4 - 67.7 µm long cladome, 253 - 145.4 - 87.5 µm long × 22.7 - 14 - 8.7 µm wide clade (Figure 7H-1.); protriaenes II: thinner, with very thin and long clades, with some bent ends, 2881.8 - 1934.8 - 646.4 µm long × 8.7 - 4.6 - 1.8 µm wide rhabdome (Figure 7H-2.); anatriaenes (n=13): very scarce, rare, with a very thin rabdome 3117 - 1216.8 - 1792.1 µm long × 17.7 - 10.7 - 4.1 µm wide (Figure 7G.). Microscleres: micro-spined sigmaspires, variable, S-shaped, 33.3 - 23.1 - 17.5 µm long (Figure 7J.)

Figure 7 Fangophilina submersa A. Specimen, B-1,2. Oxeas, C. Ortotriaene, D. Plagiodiaene, E. Orthomonoenes, F. Plagiotriaenes, G. Anatriaene, H-1. Protriaene I, H-2. Protriaene II, I. Prodiaene, J. Sigmaspires, K. Skeleton.

Habitat: Soft bottoms in mesophotic environments, 42 - 110 m (van Soest, 2017).

Distribution in the Caribbean: Guyana, Gulf of México, Colombian Caribbean.

Comments: to identify this specimen, it was compared with van Soest (2017); the only one who has reported this species for the western Atlantic. The descriptions are very similar, the author describes variations of megascleres spicules, like plagiomono-, di- and trienes (as variations of plagiotrienes), orthodi- and triene (as variations of orthotrienes) by the number and orientation of the clades towards the rabds. Therefore, in this work the same nomenclature was used due to the similarity, except for the “monoplagiotriaene” ones, which are not shaped like an ox horn, as described by the author. However, both the shape and the spicule composition coincided, thus assigning this species.

Family Theonellidae Lendenfeld, 1903

Genus Discodermia y su autor y fecha

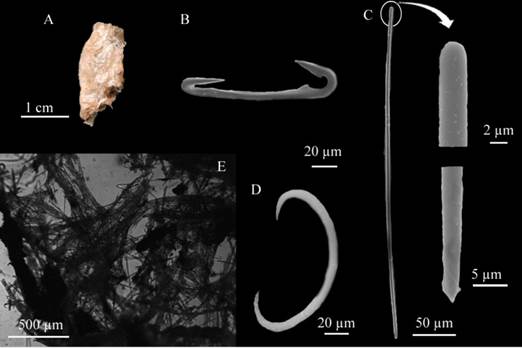

Discodermia polydiscus (Bowerbank, 1869) (Figure 8 A - G)

Dactylocalyx polydiscusBowerbank, 1869.

Discodermia polydiscus; van Soest and Stentof, 1988: 50 - 52, fig 22; Pisera and Lévi, 2002: 329, fig 3 (with additional synonymy); Rützler et al., 2009: 298. (listed).

(For additional, badly applied names and additional synonymy, see de Voogd et al., 2022b).

Studied material: INV POR1553, Isla Fuerte, 98 m, col. Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-08-03; INV POR1582, isla Fuerte, 126 m, col. Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-08-05.

Description: irregularly shaped sponge, with some polychaetes on and within the ectosome, 3 cm long × 2 cm wide, flat surface; no visible oscula, brittle consistency in the upper part, hard, difficult to cut in the lower part, medium beige-colored in alcohol (Figure 8A); Skeleton: ectosome: detachable from the discotriaenes, with some randomly visible microscleres; Choanosome: thin tracts of oxeotes supporting the skin of discotriaenes rising through the 387.4 - 309.8 -232.2 µm thick reticulation of desmata (Figure 8F - G). Spicules: Megascleres: desmata with flat stems but very wart ends, the highest diameter is reported, 573.6 - 307.1 - 193 µm long (Figure 8B), discotriaenes with irregular or oval edges, generally flat, but some corrugated or with very small protrusions, 198.6 - 174.4 - 150.2 µm long × 41.1 - 32- 22.7 µm wide rhabdus, longest diameter: 381.4 - 259 - 161 µm long (Figure 8C), oxeote (n=13) with modifications of stylotes, 698 - 442.6 - 223.7 µm long × 10.2 - 6 - 3 µm wide (Figure 8D.). Microscleres: acanthomicroxea 17.3 - 12 - 6.8 µm long × 4.2 - 2.8 - 1.5 µm wide (Figure 8E).

Figure 8 Discodermia polydiscus. A. Fragment, B. Desma, C. Discotriaenes, D. Oxeote, E. Acanthomicroxea F - G. Merged desmata network

Habitat: soft bottom in mesophotic environment.

Distribution in the Caribbean: Barbados (van Soest and Stentoff, 1988); Gulf of Mexico (Rützler et al., 2009); Colombian Caribbean.

Comments: the morphotypes were compared to Discodermia dissolutaSchmidt, 1880, which has already been reported for the Colombian Caribbean. However, the morphology of the discotriaene spicules is more irregular and is greater in size than that reported. Similarly, the desmata have more protrusions, which makes them easy to spot; with is why Discodermia polydiscus was assigned, following the comparisons made by van Soest and Stentoff (1988) although it does not have separate microscleres as they describe (microxeas and acanthose microrhabds separately), which differ in nomenclature with Pisera and Lévi (2002) who characterize acanthoxas and acanthomicrorhabds.

Order Merliida Vacelet, 1979

Family Hamacanthidae Gray, 1872

Genus Hamacantha, de su autor y el año

Hamacantha (Vomerula) agassiziTopsent, 1920 (Figure 9 A - E)

Figure 9 Hamacantha (Vomerula) agassizi. A. Fragment, B. Diancistras, C Style. D. Sigma, E. Skeleton.

Synonymy in van Soest, 2017: 127, fig 78. In addition:

Evomerula agassizi; de Laubenfels, 1936: 125. (fide de Voogd et al., 2022c).

Examined material: INV POR1483, Manaure, 210 m, col. Paola Flórez | Manuel Garrido, 2011-12-02; INV POR1577, Isla Fuerte, 128 m, col. Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-07-04; INV POR1580, Isla Fuerte, 126 m, col. Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-08-05.

Description: lobe-shaped irregular sponge, thin, 2 cm long × 1.7 cm wide, flat surface, no visible oscula, brittle consistency, easy to tear apart, light beige-colored in alcohol, somewhat translucid (Figure 9A). Skeleton: Ectosome: tangential reticulation of style tracts, thin, intertwined, 17 - 40 μm (three to five spicules) in diameter, with several diancistras interleaved. Choanosome: formed by tracts of feathery spicules 195 - 287 μm in diameter, becoming thinner towards the surface, 92 - 134 μm wide (Figure 9E). Spicules: Megascleres: straight or slightly curved, flat, spindle-shaped styes 422.1 - 383.4 - 293.1 µm long × 7.4 - 4.8 - 2 µm wide; (Figure 9C), diancistras in adult stage with sharp surfaces, only large at the apices below a keyhole-shaped opening. The middle part of the axis is rounded, 121.1 - 108.7 - 95.4 µm long × 9.3 - 6.9 - 4.1 µm wide (Figure 9B); Microscleres: rounded sigmas 13.6 - 12 - 9.4 µm in length (Figure 9D).

Habitat: thick sand bottom at 130 m deep (van Soest, 2017), soft bottoms in mesophotic environments

Distribution in the Caribbean: Gulf of Mexico (Topsent, 1920), erroneously reported from the Azores by van Soest (1984) (p. 144). Guyana shelf (van Soest, 2017).

Comments: to identify the specimen, Castellano-Branco and Hadju 2018 (table 2) was reviewed, where the valid Hamacantha (Vomerula) species are compared, given that their megascleres are styles and not oxeas. In addition, the characteristics match in shape and spiculation with the descriptions made by van Soest (2017). Several species recorded in the western Atlantic were compared: H. (V.) jeanvacelati Castellano-Branco and Hadju, 2018 do not report microscleres, H. (V.) klausruetzleri Castellano-Branco and Hadju, 2018 shows strongyles as megascleres and two categories of diancistras and sigmas, H. (V.) azoricaTopsent, 1904 has no record of megascleres or diancistras to compare and shows raphides as microscleres, H. (V.) bowerbankiLundbeck, 1902 does not report megascleres and has toxae as microscleres, H. (V.) carteri Topsent, 1904 has megascleres that are clearly larger than the specimen, H. (V.) integra Topsent, 1904 reports acanthous styles and has no microscleres, H. (V.) microxiferaLopes and Hadju,2004 has raphides as microscleres, and H. (V.) tenda (Schmidt, 1880) differs as it has toxae and lacks sigmas ((cf. Topsent 1920 (p. 9) and Hajdu 2002 (p. 667)).

Order Poecilosclerida Topsent, 1928

Family Coelosphaeridae Dendy, 1922

Coelosphaera (Coelosphaera) hechtelivan Soest, 1984 (Figure 10 A - F)

Coelosphaera (Coelosphaera) hechtelivan Soest, 1984.

Examined material: INV POR1562, Isla Fuerte, 73 m, col. Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-07-29.

Description: sponge shaped like hollow irregular fistulae measuring 4.7 cm long and 0.5 cm wide each, corrugated surface, with no visible oscula and very fragile consistency, medium beige-colored in alcohol (Figure 10A). Skeleton: Ectosome: dense layer of unclear megascleres; Choanosome: single megascleres forming strange, badly defined tracts (Figure 10F). Spicules: Megascleres: long, sinuous tylotes with slightly swollen heads, 522.6 - 384.3 - 252.8 µm long × 11.3 - 7.2 - 4.1 µm wide (Figure 10E), raphides in thick tricogragmata 734 - 347.7 - 230.1 µm long × 88.5 - 29.3 - 11.7 µm wide (Figure 10D.). Microscleres: sigmas: 53.2 - 45 - 39.6 µm long × 3.8 - 2.5 - 1.7 µm wide (Figure 10C) and isochelas: 34.4 - 29 - 20.5 µm long × 3.8 - 2.5 - 1.7 µm wide (Figure 10B).

Figura 10 Coelosphaera (Coelosphaera) hechteli. A. Fragment, B. Isochela, C. Sigma, D. Tricodragmata, E. Tylote, F. Skeleton.

Habitat: muddy and bottoms in mesophotic and deep waters.

Distribution in the Caribbean: Curaçao, type locality, Puerto Rico. (van Soest, 1984), Colombian Caribbean.

Comments: the characteristics of the specimen match in combination and size with the only record for Punta Cadena, Curaçao in the western Atlantic (van Soest, 1984) (tylotes: 533 - 386 - 268 µm long × 6 - 4 - 2 µm wide; dragmata: 330 - 306.5 - 285 µm long × 55 - 38.8 - 20 µm wide; sigmas: 60 - 48.4 - 38 µm long and isochelae: 30 - 26.7 - 22 µm long).

Forcepia (Forcepia) colonensisCarter, 1874 (Figure 11A - F)

Figure 11 Forcepia (Forcepia) colonensis. A. Fragment, B. Tylote, C-D. Forceps in different growth forms, E. Isochela, F. Skeleton.

Forcepia colonensisCarter, 1874: 248, pl. XV, fig. 47, No Carter, 1885: 110-111, pl. IV, fig 2, a-e.

Forcepia trilabis; van Soest, 1984: 66, pl. VI figs 1-2, text-fig. 24 (no Boury-Esnault, 1973: 280, fig. 32).

Examined material: INV POR1509, Isla Fuerte, 73 m, col. Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-07-29; INV POR1590, isla Fuerte, 78 m, Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-07-30.

Description: amorphous sponge, somewhat elongated, 5 cm long × 1.5 cm wide, flat surface, no apparent oscula. Soft-brittle consistency, medium beige-colored in alcohol (Figure 11A). Skeleton: Ectosome: one scab of intertwined megascleres; Choanosome: irregular array of individual megasclere spicules (Figure 11F). Spicules: Megascleres: tylotes with well-developed styles, some of them with rough deformations (Figure 11B.), very uniform, 519.4 - 471.7 - 384 µm long × 13 - 8.4 - 4.3 µm wide, large, thorny forceps in various development stages, 345.4 - 295.5 - 255.7 µm long × 11.6 - 7.6 - 4.3 µm wide (Figure 11C-D). Microscleres: arcuate isochelae in two size categories, I: 32.3 - 25.3 - 21.2 µm in length, II (n=12): 20.8 - 19.2 - 16.3 µm in length (Figure 11E).

Habitat: on coral debris bottoms at 100 m deep, mesophotic soft bottoms.

Distribution in the Caribbean: Panama, Barbados (van Soest, 1984) (described as Forcepia (Ectoforcepia) trilabis), Colombian Caribbean.

Comments: van Soest (1984b) confused it with a thin, broken development stage of the large forceps of Forcepia trilabis. Boury-Esnault (1973): 280) confused it with F. colonensisCarter, 1874a. In its current interpretation, it is likely that this is a closely but separate species. The identification was based on the Systema Porífera, where van Soest (2002) describe spicules megascleres: tylotes 330 - 360 µm long × 7 - 4 µm wide; forceps 200 - 260 µm long × 3.5 - 4.5 µm wide and spicules microscleres: large arcuate isochelae 20 - 38 µm long; small normal-shaped arcuated isochelae 15 - 20 µm long

Order Suberitida Chombard and Boury-Esnault, 1999

Family Halichondriidae Gray, 1867

Spongosorites ruetzleri (van Soest and Stentoff, 1988)(Figure 12 A - C)

? Halichondria ruetzlerivan Soest and Stentoft, 1988.

Spongosorites ruetzleri (van Soest and Stentoff, 1988); Díaz et al. 1993: 300, figs 36, 37, 43.

Examined material: INV POR1506, isla Fuerte, 73 m, col. Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-07-29; INV POR1507, isla Fuerte, 124 m, col. Paola Flórez | Erika Montoya | Andrés Merchán | Manuel Garrido, 2012-08-03.

Description: massive amorphous sponge 7.5 cm in diameter, flat surface, randomly distributed little oscula, crumbly consistency, shells of vermetids growing within and on the sponge, which, according to Díaz, et al. (1993) cause it to darken to dark brown in alcohol (Figure 12A). Skeleton: Ectosome: thick paratangential crust of smaller spicules in many directions; Choanosome: megascleres arrayed in a confusing manner, parallel or oblique to the surface, some of them grouped as 274.5 - 133 - 65 µm wide tracts (Figure 12C). Spicules: megascleres oxeas with two size classes, oxea I: long, generally spindle-shaped, some of them bent at the center or along the 937 - 747.2 - 656.5 - µm long × 34.8 - 21.6 - 13.3 µm wide spicule; oxea II: fusiform with bent at the center, 559.3 - 408 - 264.2 µm long × 17.5 - 11 - 8.2 µm wide spicule (Figure 12B.).

Habitat: deep waters, 25-173 m, on rocky or sandy bottoms.

Distribution in the Caribbean: Barbados (van Soest and Stentoff, 1988), Bahamas (Díaz et al., 1993), Colombian Caribbean.

Comments: the specimen was compared to Díaz et al. (1993), with consistent similarities in both the description and its skeleton and spicule structure, although the taxonomic identification of the genus was a complex task due to skeleton generality. Diaz et al. (1993) describe two or three size classes (600 - 200 µm long × 5 - 20 µm wide; 80 - 360 µm long × 3 - 12 µm wide; 40 - 180 µm long × 2 - 8 µm wide); in this work only two size classes were found. The differentiation of the morphotype with the presence of vermetids resulted in the assignation of this species.

DISCUSSION

Out of the 202 processed lots from the Isla Fuerte and Alta Guajira stations, only one species was recorded in the latter at a depth of 210 m, representing the deepest record in the study. This difference could be explained by the sandy substrate composition of the Colombian Caribbean continental shelf, which hinder the settlement and growth of sessile organisms, unlike hard substrates found in shallow areas. The primary reason for this are substrate instability and the high concentrations of free dissolved amino acids in the water column (Pansini and Musso, 1991; Ilan and Abelson, 1995; Rützler, 1997).

According to Invemar-ICP (2013), a hypothesis that could explain the exceptional richness and abundance of epibenthic organisms (mainly sponges) in Isla Fuerte, as well as a habitat for other taxa, e.g., the mollusks belonging to the family Siliquaridae (vermiform gastropods) and Spongosorites ruetzleri, is the location of these organisms at the beginning of the continental shelf’s descent and they are therefore affected by diapirism and gas emanation events occurring in the sector due to the San Jacinto belt subduction tectonic activity (Duque-Caro, 1984). Even though this also depends on physico-chemical factors such as current direction and speed, turbulence, and available nutrients, the constant supply of food by primary producers (mainly bacteria), which may be provided by these emanations, is another variable that can determine the composition of sessile benthic organisms in this sector (Santodomingo et al., 2007, Martínez et al., 2007). On the other hand, the identification of scleractinian coral detritus of the genus Agaricia sp. suggests that it likely originates from shallower areas. The flow from the shelf carries this detritus into deeper areas, thus creating a suitable substrate for species’ settlement (Santodomingo et al., 2007).

When comparing the 45 identified species to studies on sponge biodiversity in shallow environments of the Colombian Caribbean’s continental shelf, where at least 66 sponge species were recorded (Díaz and Zea, 2008), it can be concluded that mesophotic environments (> 50 m), harbor a significant diversity of this group. Even though these areas are not characterized by hard littoral substrates, there are sufficient conditions for larvae to settle and grow in these environments. To corroborate the greater diversity of hard-bottom vs. soft-bottom environments mentioned by Pansini and Musso (1991), it is essential to establish similarities and differences in sponge diversity between shallow, hard-bottom environments and deep, soft-bottom ones.

The preservation of the sponges identified in this study at the MHNMC since 2012, emphasizes the significance of biological collections in the scientific community as crucial repositories of information on the country’s marine biodiversity. This is a noteworthy contribution to the Porifera biodiversity knowledge in mesophotic environments of the Colombian Caribbean, particularly due the description of new records for the area

text in

text in