Echinoderms (phylum Echinodermata) are exclusively marine animals that owe their name to the rigid (calcareous) structures in the form of spines that cover their body, externally. Echinoderms are able for colonizing any type of marine habitat. These deuterostome organisms are also characterized by presenting pentaradial symmetry and reaching extremely varied sizes and shapes (Solís-Marín et al., 2014). The skeleton is formed by intradermal plates of calcium carbonate, or calcareous spicules, which articulate each other’s. Such articulations work together with the existence of a flexible connective tissue, allowing to voluntarily and quickly change the shape and rigidity of the animal, (Hendler et al., 1995; Samyn et al., 2006). Contributing to locomotion and shape changes, a unique aquiferous vascular system, which functions as vascular support, is involved in feeding and other basic circulatory functions. It is a system that consists of an internal network of channels and flexible reservoirs connected to external extensions (Samyn et al., 2006).

Currently, the Phylum Echinodermata (literally: spiny skinned animals) is divided into five living classes: Crinoidea, Asteroidea, Ophiuroidea, Echinoidea, and Holothuroidea. In Mexico, the class Asteroidea is the second best represented, with 229 species, which correspond to 28% of the described species (Solís-Marín et al., 2018). The representation of asteroids in the Caribbean Sea is less than that reported in the Gulf of California and the Pacific. The genera Astropecten, Luidia, Nidorellia, Oreaster, Pharia, Phataria, and Heliaster, are the most representative in western Mexico, Gulf of California and the Mexican Pacific (Solís-Marín et al., 1993, 2014). Compared to what was recorded for Mexico, in Cuba, a greater number of genera (13) has been described, but a smaller number of species (76) have been reported within the class Asteroidea (Abreu-Pérez, 1997; Fernández-Osoria, 2001).

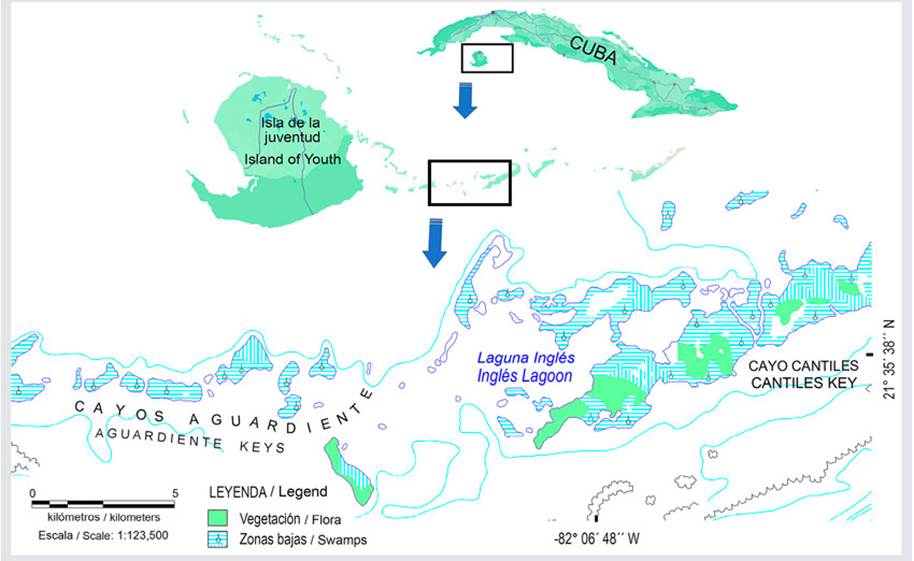

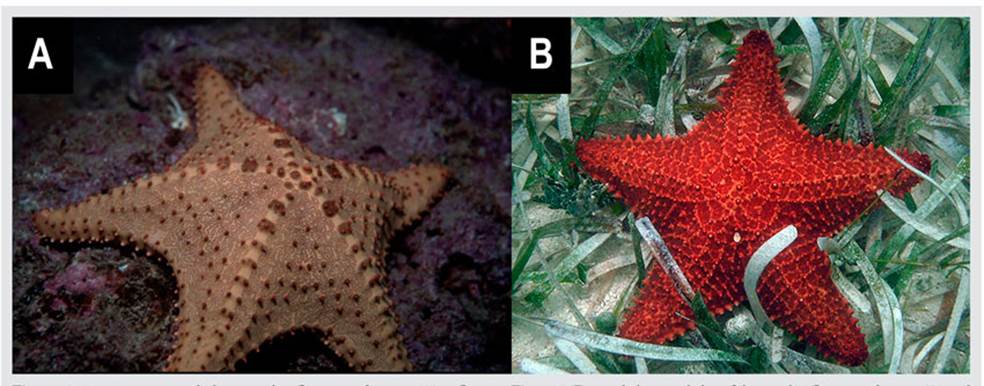

Over time, some ancient sea stars formerly included within Oreaster have been renamed while being included in other genera. Nowadays, the nomenclature of the genus Oreaster Müller and Troschel, 1842, includes only two species. The species Oreaster clavatus Müller and Troschel, 1842, described mainly in the eastern Atlantic region and whose external morphology is represented in Figure 1A, and the species Oreaster reticulatus (Linnaeus, 1758), with a broader distribution throughout the Caribbean and the only one reported to date in Cuba (Abreu-Pérez et al., 2005) (Figure 1B). The objective of this work was to present, graphically, a specimen unknown to date and a member of the genus Oreaster, within the class Asteroidea.

Figure 1 External characteristics of the species Oreaster clavatus (A) and O. reticulatus (B), based on the World Asteroidea Database (revised on 08-10-2023; at 9:07 pm).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The examined specimen was collected on September 29, 2019, in Inglés Lagoon, at Los Canarreos archipelago, south edge of the southwestern shelf of Cuba, at -82° 06’ 48” W; 21° 35’ 38” N (Figure 2). At the site, surrounded by keys basically formed by red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle L.), the depth is 3.2 m. Soft, sandy-muddy bottoms, with underwater vegetation of medium to high density and formed essentially by Thalassia testudinum K.D.Koenig, constituted the substrate at the collection site.

The atypical specimen was collected during the sampling of commercial sponges, which was carried out by direct observation swimming in apnea (free diving) within the 2 × 100 (200 m2) transepts. The atypical sea star was manually collected, after being spotted among the bottom vegetation canopies.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

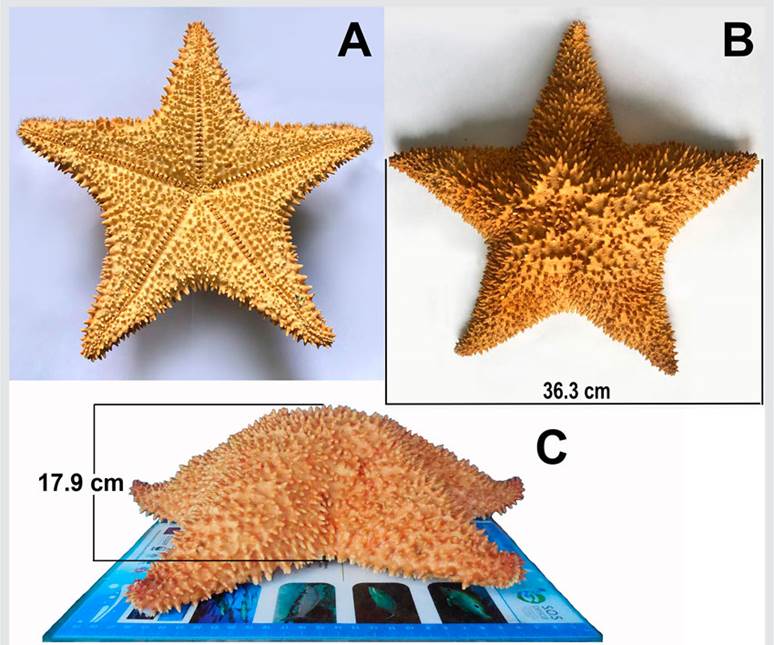

The collected specimen, called “atypical form”, looks like non previously described for Cuba and has not been reported (Figure 3). Externally, some morphological characteristics have already been described for Oreaster. The prime exception is that the pattern of spines arrangement is irregular, unlike that presented in O. reticulatus and O. clavatus. Basically, like other Oreaster species, the atypical form is a pentagonal specimen, with short arms and a raised disc that gives the appearance of robustness and strength. The abactinal plates are convex, with robust and conical spines. The super-marginal plates also have short and thick spines. The infero-marginal plates, located ventrally, and the actinal plates, are similar; the latter presenting inter-radial areas (inverted “V” shape) with one or more tubercles. Bivalved pedicellariae not included into alveoli are seen on both surfaces, although they are more numerous in the ventral region (Gondim et al., 2014; Cunha et al., 2020; Cunha et al., 2021).

Figure 3 External appearance of the new atypical form of sea star (Oreaster) collected in shallow waters of the Gulf of Batabanó, Cuba. A: Actinal (ventral) view; B: Abactinal (dorsal) view; C: Lateral view.

In the atypical form, currently described, the papular areas have numerous pores, and do not have a triangular appearance. There is no presence of continuous grooves or cords on the dorsal part of the arms and the central disc. The dorsal surface does not appear to have the reticules described for O. reticulatus. Only on the disc, some incipient cords, looking like sutures, join the largest spines, which are numerous and distributed randomly over the entire surface of the organism. Both the atypical specimen and O. reticulatus show ambulacral plates having series of five or six short, flattened, flag-shaped spines, of which the longest spines are the central ones of each series. On the abactinal surface of O. reticulatus, the spine density is between 9 and 15 spines per 9 (3 × 3) cm2. Such density is even lower in O. clavatus (Gondim et al., 2014). However, in the collected specimen, the density of spines is higher, between 14 and 22 spines per 9 cm2. The spine’s size is particularly uniform (the presence of small spines is not common), in the atypical, a phenomenon that is more appreciated in the arms than in the central disc (Figure 3B).

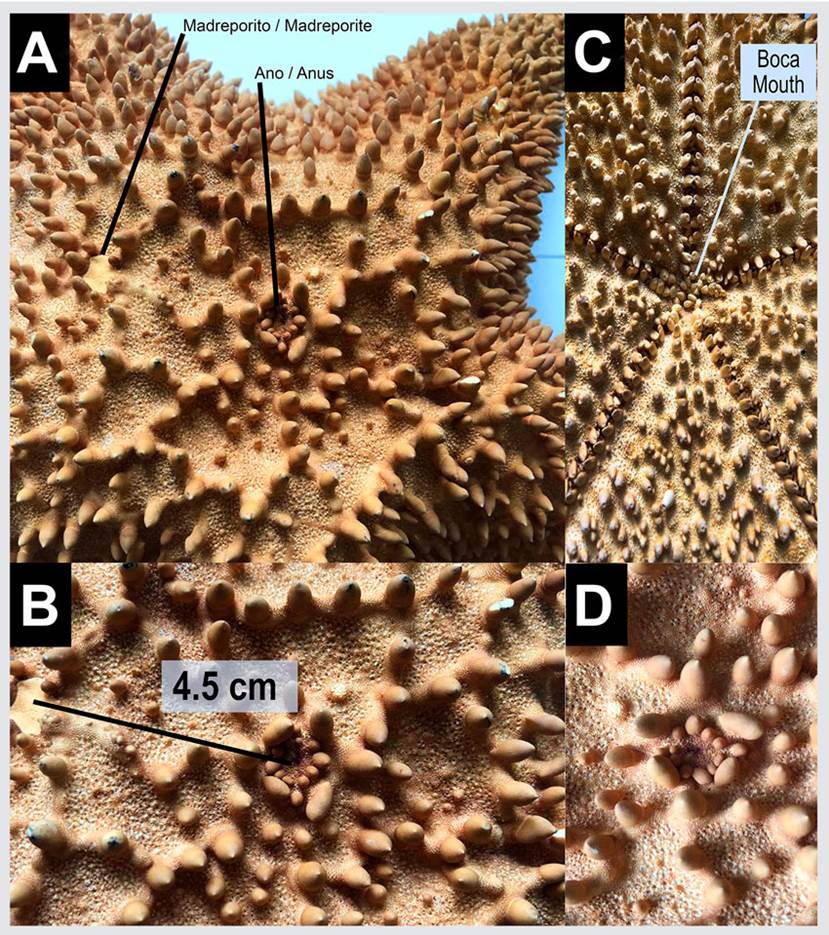

The collected specimen shows actinal plates with one to six short, conical, and robust spines. Otherwise, the actinal plates of O. reticulatus shows one or two spines. Like O. reticulatus and O. clavatus, the atypical form exhibits a small madreporite that looks like a delta wind. Such facts have been commonly described in Oreaster species (Gondim et al., 2014; Cunha et al., 2020). Nevertheless, madreporite and anus are both protected by a circle of stronger spines acting like fortification (Figure 4A). Such spines are not found in O. reticulatus nor O. clavatus. Analogously to what described for O. reticulatus, similar size spines could be found around the mouth (Figure 4C). However, the anus and mouth location, and the distance between them, are like in O. reticulatus (Figure 4B). Also, the color shade shown by the atypical form is like the often described for O. reticulatus. Nevertheless, the common different between the colors of actinal and abactinal sides, is hardly appreciated in the atypical form. The color of the collected specimen is uniformly orange (commonly found in Oreaster species). Color intensity is slightly higher in the base of the spines.

Figure 4 Mouth, anus, and madreporite location in an atypical form of the sea star (Oreaster) found in the Gulf of Batabanó, Cuba. A and B: Specific location and distances between madreporite and anus; dorsal view. C: Mouth; ventral view. D: Anus.

As mentioned, the collected specimen shows characteristics which have not been previously reported. However, there is no evidence to rule out that it is an adult specimen of the larval stages recently described as a new species within the genus Oreaster (Janies et al., 2019). Another hypothesis is that it is a new morphotype within that genus. Future molecular analyzes on the genetic material will ultimately allow us to corroborate such conjectures. Also, determining whether or not we are definitely in the presence of a new species (a fact that could also imply other taxonomic categories).

text in

text in