Introduction

The intricate networks of agribusiness chains serve as vital conduits in the global economic landscape, facilitating the journey of agricultural products from producers to end consumers while infusing value at each stage of the process. This interconnectedness has led to the emergence of globally integrated systems characterized by complex relationships and coordinated trade patterns, as noted by Ruben et al. 1. Within these networks, technological capabilities converge with advanced harvesting and post-harvest processes, fostering organizational frameworks capable of developing, manufacturing, and distributing specialized products like nutraceuticals or cosmetics.

Understanding the dynamics of value creation within the agro-industrial sector is paramount for its management and sustainable development. The concept of added value encompasses multifaceted dimensions, ranging from the monetary transactional aspect emphasized by some scholars 2,3 to the perceived utility and subjective rewards associated with goods and services 4,5. This complexity implies that value manifests through diverse elements such as quality, costs, delivery times, and innovation 6, necessitating a nuanced comprehension of its determinants and manifestations.

In the evolving landscape of agro-industrial value chains, novel market orientations and the involvement of new actors reshape value creation dynamics 7. Value generation extends beyond mere physical transformations of products to encompass enhancements in quality, identity preservation, and logistical efficiencies 8. Adaptation to consumer preferences entails strategic adjustments along the supply chain, whether through direct consumer engagement, production process modifications, or the incorporation of unique product attributes 9. Recognizing the significance of capturing value along the agribusiness chain, especially for farmers in emerging markets, underscores the potential for value addition beyond primary production activities 10. Leveraging research and development initiatives, improved marketing strategies, and advancements in processing technologies offer avenues for value augmentation and upward mobility within the value chain 11-13.

However, related questions arise in the literature such as: ¿Where can more value be appropriated in a chain? How much? 7,14-17. In this regard, research on agro-industrial chains has revolved around their mapping and diagnosis, finding that business structures in industrial agriculture are fragile in terms of maintaining competitiveness and sustainable development due to internal and external factors 6,18-21, also highlighting that in agriculture exist complex organizational networks, which are necessary to comprehend in order to include, empower and improve smallholders activities and lifestyles 17,21-26.

In summary, the research question is ¿How to successfully compete through value generation activities in agro-industrial chains? Answering this question can be valuable for companies seeking to make decisions about which business areas can strengthen in their companies or through alliances, and what strategies can be explored to improve their capabilities for easier adaptation to consumer demands. As a result of this review, we hope to contribute significantly to the existing body of knowledge on value generation strategies in agro-industrial chains, in areas of management, such as decision making, supply chain management and commercial strategies, contributing to the debate around the competitiveness of agro-industrial chains and the economic development of agriculture; which can be useful for professionals and stakeholders in this fundamental sector of global economies.

Methodology

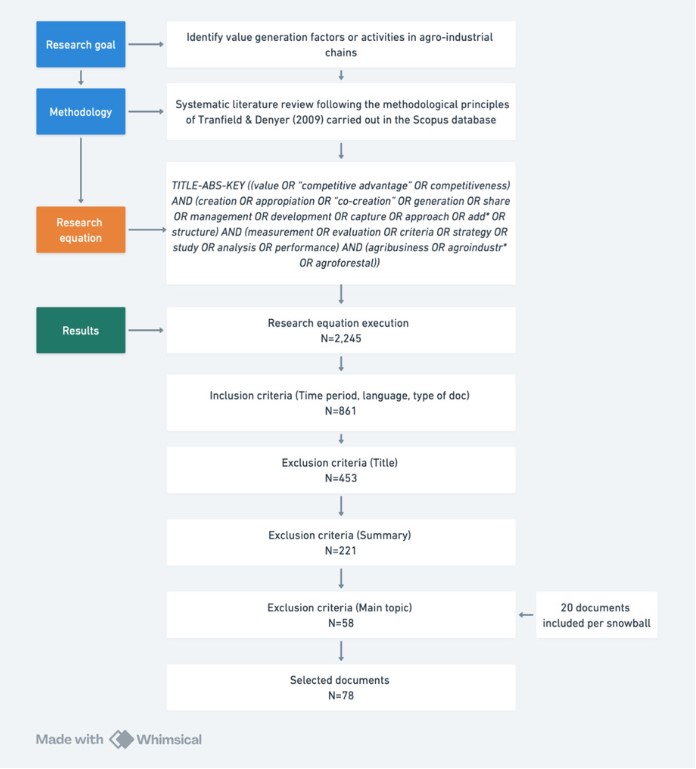

A systematic literature review of scientific articles was carried out in which value-generating activities in various chains were analyzed with the purpose of identifying the main areas or factors and the activities associated to them. Specifically, the database used for this purpose was Scopus, given its large volume of high-quality sources 27 and following the methodological principles of Tranfield & Denyer 28 to carry out a systematic literature review.

To establish the generalities of the agro-industrial value chains and those theoretical references for their analysis and measurement, the following search equation was executed:

TITLE-ABS-KEY ((value OR “competitive advantage” OR competitiveness) AND (creation OR appropriation OR “co-creation” OR generation OR share OR management OR development OR capture OR approach OR add* OR structure) AND (measurement OR evaluation OR criteria OR strategy OR study OR analysis OR performance) AND (agribusiness OR agroindustr* OR agroforestal))

The exposed terms have been used to find previous research papers where factors on global value chains are analyzed, or actors along the chain are described, dimensions are being discussed or links between farmers, cooperatives and companies have been analyzed from the perspective of the economic development, which leads to comprehend value generation, creation or capture in agro-industrial chains worldwide 6,7,29. When executing the search, without considering language restrictions, document types or areas of knowledge and for all the years available in the database (1975 - 2023), 2,245 files were found. However, the present work seeks to focus on recent literature, therefore, a refinement of the search was made considering the studies published from 2010 to 2023, in English, Spanish and Portuguese, obtaining 861 documents in a final publication stage. Subsequently, these documents were analyzed by title, summary, and main topic, selecting 58 works that were considered the most relevant and related to the topic under study. Additionally, 20 documents were included through the snowball sampling method. Although these documents fell outside the initial timeframe of analysis, they provided essential theoretical and practical foundations for analyzing agro-industrial chains due to constant mention all over the literature, finally obtaining a total of 78 documents for the literature review, as shown in Figure 1.

Results and discussion

First, the publication years of the 2245 documents found when running the research equation in Scopus were reviewed. It is found that starting in the 90s the analysis of agro-industrial chains began to be a topic of interest thanks to the contributions made by Gereffi 30 who introduced concepts related to global chains of commodities (GCC's), highlighting a notable growth since 2000 in academic productions on this topic, thanks to the relevance that Gibbon 31, Kaplinsky & Morris 32, Humphrey & Schmitz 33 Gereffi et al. 34) and Sturgeon 35 gave the analysis of the links, actors and dynamics around value chains and the various methodologies for collecting data that the authors proposed for the time.

Therefore, to compile the foundations of value chains, the most cited researchers on the topic were essential to establish definitions and methodological approaches, like, Gary Gereffi, Raphael Kaplinsky and Mike Morris, whose results revolve around understanding of the political, technological, and economic dynamics of value chains. Also, authors such as Peter Gibbon, John Humphrey, Jacques Trienekens, Roberto Feeney and Pablo Mac Clay contribute to the topic from innovation and decision making in bioeconomy environments and behavior of those markets. Regarding the affiliations of the leading researchers on the subject, it is highlighted that the knowledge has been developed mainly in universities in developed countries, especially in European countries and the United States, highlighting that only one author, Roberto Feeney, is associated with a Latin American university, as shown in table 1.

Table 1 Most relevant authors in the topic

| Author | Afilliation | Country | Published articles | Most relevant document in the topic | Publication year | Cited by |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gary Gereffi | Duke University | United States | 107 | The Organization of Buyer-Driven Global Commodity Chains: How US Retailers Shape Overseas production Networks. Commodity chains and global capitalism | 1994 | 5061 |

| Kaplisnky Rapahel | Institute of Development Studies, Brighton | England | 120 | A handbook for value chain research. | 2001 | 3880 |

| Mike Morris | University of Cape Town | South Africa | 38 | |||

| Peter Gibbon | Danish Institute for International Studies | Denmark | 45 | Upgrading Primary Production: a global Commodity chain approach. World Development | 2001 | 735 |

| John Humphrey | University of Sussex Business School | England | 51 | Developing country firms in the world economy: Governance and upgrading in global value chains | 2002 | 484 |

| Timothy Sturgeon | Massachusetts Institute of Technology - MIT | United States | 27 | The governance of global value chains. Note: Document written with Gereffi, G & Humphrey, J | 2005 | 10734 |

| From Commodity Chains to Value Chains. Interdisciplinary Theory Building in an Age of Globalization | 2008 | 604 | ||||

| Jacques Trienekens | Wageningen University & Research | Netherlands | 131 | Agricultural value chains in developing countries a framework for analysis | 2011 | 703 |

| Roberto Feeney | Universidad Austral Argentina | Argentina | 23 | Analyzing agribusiness value chains: a literature review | 2019 | 81 |

| Pablo Mac Clay | Universtät Bonn | Germany | 16 |

Definition of Agro-industrial chains

With the purpose of presenting a definition of agro-industrial chains, we start from the first uses of the term "agribusiness" introduced by Davis & Goldberg 36 who proposed a new expression to describe the interconnected functions that involve both agriculture and business. In their definition, these authors conceptualized “agribusiness” as “the sum total of all operations related to the production and distribution of agricultural products and articles manufactured therefrom” (p. 2).

Closely, the concept of value chain is created, which exposes the articulation of actors to add value to goods or services so it can be manufactured, distributed, and marketed to consumers; applied to the agro-industrial sector, it is vital for understanding this productive chain. This concept has been widely discussed in the literature as can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2 Evolution of value chain definition

| VALUE CHAIN DEFINITIONS | |

|---|---|

| Autor | DEFINITION |

| Porter 37 | “Set of activities carried out by companies but in this case, it is emphasized that it is done in order to generate additional value for their clients” |

| Sterman 38 | “It is a complex system where there is multiple interacting feedback from multiple components from production to markets in which the actions taken by actors have multiple effects at different points in the chain.” |

| Kaplinsky & Morris 32 | “It is an operating model that comprises a set of activities, institutions and entities involved in transforming, processing, transporting, adding value to the product or service, delivering it to end users and final disposal after use.” |

| Acosta 39 | “It refers to the way in which a set of actors relate based on a specific product, to add or increase its value throughout the different links, from its production stage to consumption, including commercialization, the market and the distribution" |

| Peña et al. 18 | “It refers to the commercial links and flows of inputs, products, information, financial resources, logistics, marketing and other services between input suppliers, processors, exporters, retailers and other economic agents that participate in the supply of products and services to the final consumers.” |

| Webber & Labaste 40 | “Linkages of a value chain, including all of the vertical links and the interdependent processes that generate value for the consumer, and also the horizontal bonds to other value chains that provide intermediate goods and services” |

| Bellú 41 | “A set of ‘interdependent economic activities’ and a ‘group of vertically linked economic agents’” |

| WORLD BANK - FAO - GIZ - OIT -USAID Cited by Zhou et al. 25; Donovan et al. 42; Akyüz et al. 43 | “Describes the full range of value-added activities necessary to bring a product or service through the different phases of production, including the acquisition of raw materials and other inputs.” |

| United Nations Industrial Development Organization- UNIDO Cited by Donovan et al. 42 | “Actors connected along a chain that produce, transform, and bring goods and services to end consumers through a sequenced set of activities.” |

| International Center for Tropical Agriculture - CIAT Cited Peña et al. 18; Donovan et al. 42 | “A strategic network between a number of independent business organizations, where members of the network engage in extensive collaboration” |

The concept of value chains, as explored across various definitions, exhibits a significant consensus on several key dimensions, underscoring a shared understanding of its foundational aspects. Central to all definitions is the principle of value addition, where activities such as production, processing, transporting, and delivering goods or services incrementally add value for the end consumer. This notion is consistently recognized from Porter's 37 emphasis on generating additional value for clients through a set of activities, to the World Bank and others 25,43) comprehensive view of the full range of value-added activities necessary through different phases of production. Furthermore, the complexity and interactive nature of value chains are widely acknowledged, highlighting the system's dynamic interactions and feedback loops, as noted by Sterman 38. The involvement of a diverse set of actors and institutions across the chain, including suppliers, processors, and retailers, is another area of agreement, emphasizing the collaborative and interconnected framework essential for transforming raw materials into final products that reach consumers.

Despite the broad consensus on these core attributes, several gaps emerge in the conceptualization of value chains that reflect evolving considerations in the field. Notably, discussions around governance structures and power dynamics within value chains are less explicitly addressed. This omission overlooks the significant impact that governance has on the efficiency, equity, and sustainability of value chain operations. Similarly, sustainability and ethical considerations, while implicitly connected to value addition and actor collaboration, lack direct emphasis in most definitions. This gap is notable given the increasing consumer and regulatory demand for sustainable and ethically sourced products. Additionally, the role of technology and innovation in transforming value chains, enhancing efficiency, and opening new markets is another area that receives inadequate attention, suggesting a need for updated conceptual frameworks that reflect the digital transformation's impact on global supply chains. Lastly, the active role of consumers in influencing value chain dynamics, beyond being the endpoint of value delivery, suggests a more interactive and demand-driven perspective of value chains that current definitions do not fully capture.

Based on the above, the definition of agro-industrial chains is expanded by Kaplinsky and Morris 32, adding to the activities and processes of sowing and harvesting, the multiple stages of manufacturing production, which include physical transformation and the provision of various services to the producer, with the ultimate objective of delivering the product or service to final consumers and managing its disposal after use. This will be precisely the definition to be used in this research, considering that it is the most exhaustive as it covers all the links from primary production to delivery of the manufactured products to the final consumer. Therefore, the value can be added along this huge range of activities, which in the following section are explained according to business areas.

Value generation factors in agro-industrial chains

To study agribusinesses, global commodity chains, global value chains and hence agro-industrial chains, many methodologies were developed to analyze and diagnostic actors and transaction dynamics 6,31-35, “which is a mandatory first step to delve into value chain competitiveness and performance” 29. According to these authors, these methodologies can have different approaches of analysis, starting from the product level, they involve measuring the input-output flows based on a defined functional unit of a commodity, without the need for site-specific data or even nonspatial level because they describe the input-output flows within a specified economic area 44. Furthermore, Kaplinsky & Morris 32 provide a comprehensive overview of various types of value chains, distinguishing them according to their governance structures and orientation towards demand and supply, analysis that turns out to be complementary to the one proposed by Martinez and Steward 45 where value chains are analyzed from supply push factors and those motivated by demand pull mechanisms. Additionally, Yanes-Estevez et al. 46 categorize agribusiness value chains based on the degree of environmental uncertainty they face, quantitatively evaluating 27 variables and ranking them from high to low perceived uncertainty. This nuanced understanding of value chains highlights the importance of context in analyzing and strategizing for value chain development and optimization.

In that sense, to analyze the whole value chain, this must be considered as an economic unit, with a common business goal 29, which can be affected by aspects controlled by the government, such as fiscal policies and regulations around the commercialization of agricultural products. Also, there are uncontrollable aspects, such as the climate, the entry of new technologies or biotechnological innovations. In addition, quasi-controllable aspects appear, such as new competitors, competition between chain agents, bargaining power between suppliers and customers and demand conditions, aspects related to chain governance and Porter's diamond principles 37. Ultimately, there are controllable aspects by the company, as those that can be modified, such as strategy, products, technology, human resources policies, research, and development, among others 47; these are the ones on which this research focused.

On the other hand, extensive studies have been conducted in various countries, including India, China, Ghana, Kenya, Zimbabwe, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam, Australia, Brazil, Peru, Colombia, the Netherlands, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Indonesia. These studies encompass a wide range of agro-industrial chains, such as avocado, beef, pork, forestry, fishery, cocoa, coffee, rice, sugarcane, maize, cassava, horticulture, floriculture, black tea, dairy products, castor beans, potatoes, tomatoes, cereals, fresh and dried fruits, legumes, oil crops, and broccoli. This comprehensive research provides a broad and in-depth perspective on the study of agro-industrial chains globally.

With the purpose of organizing them in a coherent manner to the business areas, Brenes et al. 48 sets five value generation poles: marketing, industry scope, operational skills, governance, and innovations. According to this classification, Table 3 lists authors who, within their research, contributed or proposed factors or activities that generate value in agribusiness.

Table 3 Value generation factors in agro-industrial chains

| Factor | Activity | Authors who mention it |

|---|---|---|

| Marketing | 1. Packaging | 23,48-56,64 |

| 2. Branding | 16,23,48,49,52,54,56-60 | |

| 3. Product offer | 16,23,48,49,52,54,56,59,61-68 | |

| 4. Personal interaction | 26,49,54,56,61,65,66,69 | |

| 5. Support service | 26,49,56,64,66,69 | |

| 6. Niche products | 16,49,54,56,67 | |

| 7. Certifications | 24,48,49,54,56,62,70 | |

| Industry scope | 1. Vertical Integration | 6,14,16,26,48,50,52,54,55,62-64,66,69,71-76 |

| 2. Horizontal Integration | 6,48,51,52,54,55,62,64,66,69,72,74-76 | |

| Operational skills | 1. Product quality | 14,16,23,26,48,52,57,59-67,69,71,73,74,77-79 |

| 2. Technical efficiency | 6,14,23,51,52,57,61,63-69,74,78-81 | |

| 3. Delivery performance | 6,14,23,26,52,54,55,57,61,69,73 | |

| 4. Industry knowledge | 6,23,54,63,64,68 | |

| 5.Access to financing/investment | 6,23,54,64,82 | |

| 6. Education/skills | 6,16,54,61,62,64,65,68,71,74,80 | |

| 7. Advisory or consulting service | 54 | |

| 8. Allocation Efficiency | 65,72,80,83 | |

| 9. Asset performance | 23,65,77,80,83 | |

| 10. Precision farming | 54,65 | |

| 11. Infrastructure | 6,23,62,64,71,74,76,77,78,83 | |

| Governance | 1. Formalization of a formal board of directors | 48,74,76 |

| 2. Information access/sharing | 23,52,54,62,64,69,74,76,82 | |

| 3. Trust | 52,54,62,64,69,74 | |

| 4. Policies and regulations | 54,62,63,71,72,74,76 | |

| 5. Inclusion | 54,62,63,74,84 | |

| 6. Communication | 6,54,62,64,74 | |

| Innovation | 1. Invesment R+D | 6,16,48,51,54,57,63,66,68,71,73,75,76,78,81,85 |

| 2. New processes | 16,48,54,59,63,68,73,77,81 | |

| 3. New products | 16,48,54,59,62,64,73,81 | |

| 4. Sustainability | 16,26,29,62,66,70,72,74 |

In particular, the marketing dimension reveals that activities such as branding and diversifying product offerings are frequently cited as significant value generators within agro-industrial chains 23,62. Specially, branding rents, derived from name prominence 6, have been exploit by major players like Nestlé and Danone in the milk sector, and Starbucks and Juan Valdez in the coffee sector, as well as Hershey, Toblerone, and Milka in the cocoa sector 6,31.

Furthermore, the development of appealing packaging and the enhancement of personalized engagement during sales processes are key strategies that ease sales processes. Mvumi et al. 51 underscore the dual importance of innovative packaging solutions, which ensure product integrity for commercialization and appeal to wholesalers and end consumers, thereby driving sales. The synergy between improved packaging and effective branding strategies facilitates consumer decision-making, enhances product perception, and bolsters brand image. Additionally, presenting a wide product range and offering quality and transparency certifications are critical factors that streamline consumer choices at the point of sale. For example, in coffee, cocoa, cotton, soybean and palm oil chains, certifications such as Rainforest Alliance and UTZ are highly attractive to consumers 16,24,50,62.

In addition, the literature robustly acknowledges the significance strategic logistics and commercial operations play a crucial role in yielding benefits for all stakeholders, particularly through the integration of the activities described in the first three factors of the previous table. For instance, in the Dutch cut flower market 14, competencies spanning the first to the third factors have been combined to build a robust florist market in Colombia. This success is largely based on the capabilities of Dutch producers, who have improved their sales and auction structures, contributing to the standardization of production. These efforts have resulted in greater foreign market quotas and have motivated strategies associated with relational rents, strengthening alliances between clusters, producers, and firms 6. Additionally, organizational rents have been achieved through effective product distribution and marketing, highlighting the empowerment of growers and strengthening the upstream phase, which subsequently improves the performance of the entire value chain.

However, some value chains 6,16,52,69 have been significantly shaped by both horizontal and vertical integration, with a strong emphasis on technical efficiency. The cocoa value chains exemplify these efforts 61,63,67,68,72,77. Despite these advancements, these chains encounter challenges related to cost optimization, which particularly impacts producers and can lead to management myopia. The literature underscores the importance of delivering quality products, ensuring timely delivery, and equipping personnel with the necessary skills and education. It further highlights the integration of these activities through marketing and innovation strategies, which depend on the collaboration of the various actors that constitute the governance of the chains.

A gap is evident between these factors, as capabilities are often developed only in the logistics area, leaving other capabilities, such as marketing, underexploited despite their proven effectiveness in other types of chains. Leveraging the skills of firms in these areas can contribute to the development of competitive strategies. The previous cases studied have shown that integrating these elements can yield positive results, suggesting a pathway for improving performance from upstream to downstream.

Also, regarding operational skills, activities such as financial access, consultancy services beyond traditional product offerings, asset performance detailing, and precision agriculture practices have significant potential to enhance crop productivity and support administrative decisions 86,88,89 since such advancements hold promise for addressing global food security challenges and enhancing overall economic performance. For example, Bertazzoli et al. 87 conducted financial analyses and price investigations across tomato, milk, and cereal chains, revealing a tendency for downstream entities to capture a greater share of value. These findings underscore the importance of further research to understand and address disparities in value distribution along agro-industrial chains, ultimately fostering more equitable and sustainable agricultural practices.

Nonetheless, the management of agro-industrial chains demonstrates a significant emphasis on innovation, particularly through investments in research and development (R&D), which holds implications for various aspects within the sector. This strategic focus underscores the importance of enhancing resource and capability development within agro-industrial management to effectively adapt to evolving market dynamics. Notably, this area garners considerable attention from major players in the downstream phase of the chains. These entities are pivotal as they capture a significant portion of the value through transformation processes and continually innovate in product development. Being near the final consumer, they have firsthand insights into consumer behavior, preferences, and emerging trends. Moreover, research and development efforts must encompass the study of technology life cycles. Such analyses provide valuable insights into the investment and knowledge surrounding the improvement of techniques, machinery, and systems related to specific crops. Understanding technology life cycles is instrumental in guiding decision-making processes in research and selecting strategies for adoption within agro-industrial chains. Effective technology management is critical for achieving a competitive advantage through the seamless integration and deployment of innovation aligned with the organization’s strategic, operational, and market objectives 90,91.

Lastly, while numerous authors acknowledge the importance of governance and its dynamics within the methodologies for analyzing value chains, only a limited number have mentioned how these elements influence the competitiveness of agro-industrial chains. These authors considered that strengthening ties between actors through trust, collaboration and the study of policies and regulations favors cohesion between activities and leads to the generation of closer ties between entities, the result of which is reflected in greater integration of the chain and the use of resources and capabilities between actors 52,62-64.

Regarding the relevance governance and policies represent in value chains mapping, current trends are related to sustainable agricultural practices, enhancing productivity, and ensuring equitable distribution of benefits. For instance, policies aimed at improving infrastructure, such as transportation and storage facilities, articulated specially by cooperatives, crucial for reducing post-harvest losses and improving market access for smallholder farmers. Furthermore, subsidies and financial support for technological adoption can enhance technical efficiency and competitiveness in global markets. In countries like Colombia and Ghana, Kenya, government initiatives to support several agro-industrial productions from agricultural products have also opened new avenues for value addition 67,72,74,82,84.

In essence, efforts must also focus on enhancing the infrastructure for information sharing and providing targeted training programs to build organizational and technical capacities. By overcoming these barriers top entities on countries develop many policies for agriculture enhance, to contribute to greater resilience, adaptability to market conditions, and ultimately improve their overall competitiveness on the global stage 52,54,62,63,71,72,74,76.

However, there is an ongoing debate about the balance between promoting large-scale agribusinesses and supporting small-scale farmers. Effective public policies should focus on creating a conducive environment for both, ensuring that smallholders are not left behind. This includes providing education and training programs, facilitating access to credit, and encouraging the formation of cooperatives to strengthen bargaining power 17,24,59,73. Additionally, policies should promote environmental sustainability and address the social impacts of agro-industrial expansion. This observation highlights a significant gap in the literature, underscoring the discrepancy between the theoretical recognition of the potential impact that enhanced access to information, trust among stakeholders, and supportive policies and regulations can have on improving value chain competitiveness, and the empirical evidence supporting this assertion.

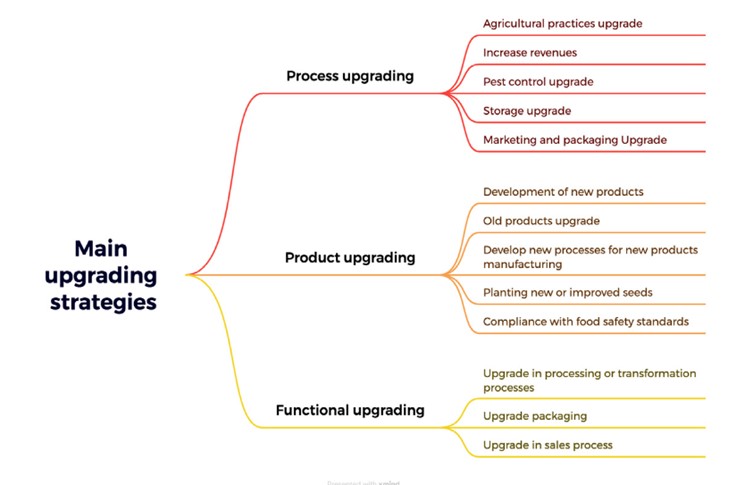

Now, starting from clearer notions of the perception of value according to various authors, the literature presents a series of improvement strategies to create value, which require increasing the capabilities of farmers and creating new commercial relationships between all strategic partners within the supply chain 24. However, engaging in these strategies does not necessarily work in a directly proportional way, that is, when executing them, better results are obtained, which in other words translates into capturing value 15. To direct efforts effectively, Humphrey and Schmitz 33 propose four typologies:

process modernization: achieving more efficient production through reorganization.

product improvement: move to products with higher unit value.

functional upgrade: increase skill content.

inter-chain improvement: apply the skills acquired in one function to a different sector/chain.

Much more specifically, Trienekens 6 disaggregates this typology as presented in Figure 2, also adding that other forms of "improvement" are equally important, being able to combine some of the previous categories or even go beyond them, such as delivering larger volumes, matching or increasing standards and certifications, meeting logistics and delivery times, receiving better payment for the same product, which translates into fair trade 22.

However, selecting improvement processes is not simple and the probabilities of optimization can be influenced by the governance, nature and limitations present in the industry being analyzed 21) (92-94 since these factors can facilitate certain forms of improvement 55. For example, relational governance can facilitate improvement through knowledge sharing and joint problem solving (20), resulting in skill development and product differentiation. Similarly, modular governance can foster improvement through innovation and process improvements 34.

On the other hand, captive governance may limit opportunities for improvement in that it discourages modernization due to lack of supplier competence and capability 34 but provides opportunities to coordinate supplier development programs of small farmers. The complexity of the transactions, as well as the ability to codify them, are high, while the capabilities of the supplier base are low, which is favorable for vertical integration 24.

This can be seen in coffee and sugarcane chains in Brazil, palm oil, cocoa, coffee in Colombia and Ecuador, rice in Thailand, and tea in Kenya are characterized by a lack of cooperatives and difficulties for integration, which significantly hamper their efficiency and competitiveness. The absence of robust cooperative structures and limited collective action among the various segments of these supply chains lead to fragmented operations and poor coordination 53,57,59,67,72,81,84,95. This disjointedness results in inefficiencies, such as increased production costs, inconsistent product quality, and delays in meeting market demands. Additionally, inadequate communication channels and lack of trust among stakeholders further exacerbate these issues, hindering the seamless flow of information and innovation adoption 52,54,62,64,69,74. To address these challenges, it is essential to foster a collaborative environment through the establishment of cooperatives and the implementation of policies that ensure equitable representation and participation of all actors involved.

Conclusions

The review of literature pertaining to value creation within agro-industrial chains highlights valuable insights while also revealing notable limitations in the evidence base. One of the key limitations identified is the lack of empirical evidence on the impact of certain factors such as financial access, consultancy services, asset performance detailing, and precision agriculture practices on value creation. Despite their potential significance in enhancing crop productivity and supporting administrative decisions, the scant empirical data available underscores the need for further research to explore their tangible effects within agro-industrial chains. Without robust empirical evidence, it becomes challenging to accurately assess the effectiveness of these factors in driving value creation and informing strategic decision-making processes for stakeholders across the value chain.

Another notable limitation in the existing literature is the abundance of frameworks for mapping and evaluating value chains, often lacking in specificity regarding strategies for enhancing competitiveness. While numerous frameworks exist, those driving improvements and competitiveness tend to be spearheaded by downstream enterprises. Consequently, there is a need for frameworks or roadmaps that empower large enterprises or stakeholders to devise strategies for bolstering competitiveness across all value chain segments.

Moreover, the review also acknowledges potential biases, such as publication bias and selective reporting, and the possibility of excluding relevant studies due to publication status or language barriers. This could lead to an incomplete representation of the evidence landscape, and researcher bias might influence the selection and interpretation of studies. Therefore, caution is advised in drawing definitive conclusions based on the synthesized evidence.

For practitioners within the agro-industrial sector, the identified gaps in empirical evidence underscore the importance of adopting a cautious and evidence-based approach to decision-making. Policymakers can use these findings to prioritize research funding and development initiatives aimed at addressing the identified knowledge gaps, thereby fostering innovation and sustainability within the agro-industrial sector. Future research should aim to generate robust empirical evidence on the efficacy of various value creation factors, facilitating informed decision-making and advancing our understanding of value chain dynamics.

In conclusion, value creation encompasses optimizing operational processes, marketing, innovation, and efficient interaction between chain links, all of which enhance competitiveness. Despite progress, key research questions remain unresolved, particularly concerning governance, sustainability, and technological innovations. Addressing these gaps will foster a comprehensive understanding of agro-industrial chains, informing future improvement strategies and highlighting the importance of collaboration, evidence-based decision-making, and ongoing research efforts.

Competitiveness in agribusiness hinges on tangible interactions among market actors, including inter-firm relationships, market participation dynamics, and profit elasticity. These factors, combined with innovation, technology transfer, and increased productivity, correlate positively with higher profits, market share, and growth prospects. Strengthening knowledge in these areas will drive sustainable growth and competitiveness within agro-industrial chains.

Finally, improvement strategies within agro-industrial chains must consider various dimensions such as process modernization, product improvement, and functional upgrade, with governance structures influencing their effectiveness. Collaboration among stakeholders is essential to drive competitiveness and sustainability within the sector, emphasizing the need for evidence-based decision-making and continued research efforts. Overall, this study underscores the complexity and importance of agro-industrial chains in driving value creation and economic development on a global scale.