Introduction

As Crystal (2003) mentioned in “English as a Global Language,” there has never been a time when such an urgent need for a global language was required. As a result of this, English continues to play a major role for individuals communicating around the world, making English a lingua franca that allows people to participate in a globalized community.

Bearing these circumstances in mind, many countries have adopted English into their national curricula, often acknowledging its importance as a lingua franca for international trade, international relations, and education. Colombia has not been the exception in recognizing the importance of English for education, national growth, and competitiveness, as evidenced in projects carried out by the Ministry of National Education (Colombia, Ministry of Education, -hereinafter MEN), such as the National Bilingual Program 2004-2019, Program Strengthening of Foreign Languages Competences (2010-2014), Colombia Very Well (2015-2025), the creation of English textbook series Please! and Way to Go. In the same vein, educational institutions have taken on bilingual or even international curricula thereby requiring more content to be taught in English. Despite efforts, such as including English in the curriculum and developing an English as a Foreign Language (EFL) program for the Colombian context, educators continue to face various challenges since they now see themselves immersed in learning scenarios where they not only teach English, but they teach through English. This is closely related to Graddol’s (2005) claim that the role of teachers has changed now that English has become a world language and a generic language skill, not a foreign language, which might have been the consequence of a global shift toward combining content and language, in which English is used as a medium of instruction, and not only as a foreign language.

The CLIL approach has been used as a response to the fast-growing challenges of globalization that have taken education (Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010) by surprise. These challenges come from many angles, such as professional development plans, new and improved curricula, and a better understanding of the role of intercultural awareness in education. In any event, globalization has led countries to embrace foreign and/or second languages learning, thereby making CLIL a potentially viable solution for educational authorities concerned with developing more advanced linguistic proficiency in their communities. Since a CLIL approach is not only concerned with improving foreign language competences, it can serve as an alternative to education. Where both language and content professionals can both take advantage of this approach to enhance academic results.

Nevertheless, despite CLIL’s growth and rise in popularity in education throughout Colombia, as seen in studies conducted at all levels of education (Archila & Truscott de Mejía, 2020; Corrales, Paba-Rey, Lourdes, & Escamilla, 2016; Fandiño Parra, 2014; Leal, 2016; Otálora, 2009), the implementation continues to be a challenge. This is a concern, since CLIL practitioners are not fully aware of the diverse aspects of CLIL nor do they understand that CLIL is context-oriented. Educational institutions attempt to apply a successful model, without any changes or modifications, to their own schools, thereby adding to the challenge (Curtis, 2012; Torres-Rincon & Cuesta-Medina, 2019). This challenge interferes with the overall academic progress in the classroom, thereby ignoring the realities, (i.e. learners’ needs vs. institutional requirements related to bilingual education) and ultimate changes that are needed in the classrooms (Abad, 2013; Freeman & Freeman, 2014; Truscott de Mejía, 2012). A lag in the above mentioned challenges can be attributed to several issues, amid which two stand out: resources to fund quality educational programs and lack of both in-service and pre-service teacher training courses to better prepare teachers for the demands and challenges of 21st-century education (Archila & Truscott de Mejía, 2020; Camargo Cely, 2018; Cuesta Medina, Anderson, & McDougald, 2017). These two issues have hindered Colombian educational institutions’ progress in an atmosphere where school administrators are still reluctant to rethink the traditional teaching approaches to language and content, which is crucial for CLIL to work (Mejía-Mejía, 2016; Mora, Chiquito, & Zapata, 2019; Usma, 2009).

The focus of this study was, first, to get a clearer picture of the perceptions and knowledge regarding content and language integrated learning of English professionals teaching content through English after participating in online context-oriented training program. The research gathered information on teachers’ expectations about CLIL training programs to determine where to start in terms of the implementation of CLIL teacher development. Finally, the research attempted to examine whether teachers’ perceptions, and knowledge about CLIL changed after the teacher development period that was studied and gather useful information about teachers’ expectations for future training.

This study, which is a part of a larger study (CLIL State of the Art project in Latin American educational institutions), including learner’s and teacher’s attitudes toward CLIL only reports on a relatively small number of participants in Colombia. It focuses on 26 content-based teachers’ knowledge and perceptions toward CLIL and bilingual education. The results revealed that their knowledge of CLIL increased, thereby influencing their beliefs about teaching in bilingual learning environments. Findings also revealed that teamwork and administrative support are crucial factors for a successful CLIL implementation, as well as the need for in-service teacher training to help increase awareness and knowledge of CLIL and bilingual education. Furthermore, it was revealed that merely knowing about the theoretical aspects and factual knowledge on CLIL does not automatically translate into practical understanding of how to implement the approach.

Theoretical Framework

The following discussion examines the constructs that underlie the study at hand and provides insights into what they represent. In addition, a short report on previous, similar studies related to bilingualism and English in Colombia, CLIL in primary education, and teacher training framed around CLIL is made.

Bilingualism, English, and CLIL in Colombia

In Colombia, there is no consensus as to what is precisely meant by the term “bilingualism.” Most people take it to mean “proficiency in the use of the foreign language” (Rey de Castro & García, 1997). But the Colombian Ministry of Education (Colombia, MEN) defines bilingualism as different degrees of mastery with which an individual manages to communicate in more than one language and culture (Colombia, MEN, 2006). Hamers and Blanc (2000) sustained the notion that bilingual education refers to any system of school education in which, at a given moment in time, and for a varying amount of time, simultaneously or consecutively, instruction is planned and given in at least two languages. The National Bilingual Program (NBP, hereafter) (Colombia, MEN, 2006) has established the need to learn English in Colombia, transforming bilingual education into the first option for learning English. It provides guidelines for fostering bilingualism nationwide and promoting an inclusive vision of bilingualism (British Council, 2015; McDougald, 2007). It also requires that, by 2019, all secondary school graduates should be at the B1 level according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), while university graduates should be at B2 (Colombia Aprende, n. d.; Colombia, MEN, n. d.).

Several factors have favored the teaching of language and other content (i.e. Math, Science, Geography or Physical Education) through CLIL in Colombia, and one of them is the many varieties of programs and practices that have cropped up in the country’s private bilingual schools (Truscott de Mejía, 2004), where English is used to teach multiple or all content areas, known as content. According to De Mejía and Fonseca (2008), present-day bilingual institutions can still be classified into three groups. The first group corresponds to international bilingual schools, which have direct links with one or more governmental organizations from foreign countries (i.e. embassies, consulates), keep regular contact with the foreign language in the curriculum (over 50 %), students often have the opportunity for direct contact with the foreign country through exchanges or supervised visits organized by the school, and graduates are required to pass international exams for the foreign language. The second group of bilingual schools is known as national bilingual schools; these are national institutions that aim at a high level of student proficiency in at least one foreign language, they have a high degree of exposure to the foreign language and use two or more languages as a vehicle of instruction in different curricular areas, their administrators are Colombian nationals and most teachers are Colombian bilinguals, these schools also require their graduates to pass an international examination for the foreign language. The third group corresponds to schools with intensified foreign language programs; the great majority of these institutions were founded by Colombians, their administrators are nationals, and most teachers are Spanish monolingual, except for those teaching EFL, who are bilingual. They dedicate an average of ten to fifteen hours per week to learning a foreign language as a subject, but this is not used as a medium for learning any other curricular area. They often-but not always-require their students to pass a foreign language exam before completing their studies.

Along with the Basic Learning Rights (BLRs) launched in 2016, the Colombian MEN published the Suggested Curriculum Structure (Colombia, MEN, 2016) for grades Transition (4-5-year-olds) up to 11th (16-18-year-olds), which comprises suggestions for scope and sequence, syllabi, methodology and assessment to serve as input for planning, implementing, evaluating, and revising the English curriculum in schools nationwide. Within its pedagogical principles, the document proposes the integration of some elements of CLIL at the transition to fifth-grade levels in order to have a cross-curricular element that enriches and mediates the English language learning process. Furthermore, some aspects of the CLIL approach have been considered as a reference, such as the communication in which functional English is proposed, cognition, use of basic interpersonal communication skills (BICs) and cognitive academic language proficiency (CALP). Although not all of the CLIL principles are present, the ones mentioned above can be used to design tasks and projects in other academic subjects in school (democracy and peace, sustainability, health, and globalization), in which a cross-curricular approach is used, promoting the learning of the foreign language through disciplinary content and going beyond the simple acquisition of linguistic tools.

As a result of the growing variety of bilingual institutions in Colombia, the educational system has been experiencing new changes, such as, more content subjects being delivered in English, knowledge on what can be done with English aside from traditional communicative foreign language lessons. These changes have surfaced from the bottom-up, meaning that parents and schools are in search of increased quality education in the private sector as seen in the vast amount of bilingual schools across the country (Truscott de Mejía, 2015). Nevertheless, there is a pressing need for well-trained educators who can implement the new policies aiming at the nationwide bilingualism goals (Colombia Aprende, n.d.; Colombia, MEN, 2019) of finishing secondary school with a B1 CEFR and completing higher education with a B2 CEFR.

Muñoz (2002) argued that there is a great body of psycholinguistic research which reports significant benefits derived from the implementation of this approach and that it may constitute a way of providing a more intense exposure to the language and more and richer opportunities for using the language in meaningful ways. Dalton-Puffer and Smit (2007) concluded that CLIL students can reach significantly higher levels in a foreign language than those who learn by conventional foreign language instruction methodologies.

Furthermore, Marsh (2002) claimed that CLIL is a powerful pedagogical tool that aims to safeguard the subject being taught, while promoting language as a medium for learning. De Bot (2002) explained that approaches like CLIL are needed to face the challenge of achieving high levels of proficiency in foreign languages by linking form and content in language learning while having limited exposure to the target language. In the same vein, Muñoz (2002) claimed that using foreign languages as the medium of instruction of content subjects may be the only way of providing enough exposure to those languages to guarantee the successful learning of two additional languages in scenarios where there may not be enough time to devote to foreign language teaching.

CLIL Research in Primary Schools in Colombia

A number of studies have been carried out on CLIL implementation, strategies used in the content-and-language-classroom, as well as professional development plans for CLIL-oriented teachers. These studies attest to CLIL’s continuous response to combining language and content in Colombian classroom. The following studies demonstrate that CLIL has been used in various Colombian school models. However, these studies also demonstrate that there is a lack of true CLIL competences among teachers, which in turn highlights the need for more formal professional development when implementing CLIL.

For starters, Murillo-Caicedo (2016) worked on a CLIL teacher training intervention proposal for non-CLIL primary content teachers at a bilingual school in Bogotá, Colombia, where a proposed training plan was devised to help both content and language teachers with the basic competencies needed to become successful CLIL practitioners. Also, Curtis (2012) conducted a small study inviting Colombian teachers to reflect on their needs when implementing CLIL. The results identified key gray areas regarding CLIL implementation. Curtis divided the reflections, teacher´s questions and concerns into three key categories, namely CLIL in the Colombian context; the implementation of CLIL; and the fundamental concepts of CLIL. Torres-Rincon & Cuesta-Medina (2019) later examined the factors and conditions that intervene in the implementation of CLIL in diverse Colombian educational contexts, five private schools from different cities and towns in Colombia. Their study revealed that Colombian teachers still find difficult understanding CLIL as an approach that goes beyond the mere usage of the target language in content. However, Cano-Blandón (2015) explored how geography and history classes were delivered at a private school in Medellín, Colombia evaluating its implementation based on CLIL proposals. The results showed that teachers did not have a clear approach to balance the integration of content and language in their classes because they did not have the training to do so. Additionally, Cano-Blandón claimed that the lessons were teacher-centered and lacked critical thinking and higher-order thinking skills, and teamwork amongst content and language teachers was almost nonexistent.

However, other studies have also looked into CLIL as an approach to teaching subject areas in primary school, such as Mariño (2014), who investigated how some of the characteristics of a content-based English class could be taught using a CLIL approach in a 5th-grade class at a rural bilingual school in Boyacá, Colombia. Results revealed that, despite some positive characteristics that go hand-in-hand with CLIL, such as code-switching, non-verbal communication strategies, and the use of prior knowledge, classes were content-led and lacked some of the characteristics of a CLIL class, including the learning of language as a result of a solid grounded CLIL lesson plan.

Other studies have implemented CLIL-oriented solutions/strategies in the classroom to combine both content and language. For example, research conducted by (Bedoya Restrepo, León García, & Moncada Henao, 2016; Jaramillo, Opina, & Reinoso, 2016) focused on analyzing the reflections and insights of content language teachers and primary and secondary school students towards the implementation of a CLIL-based bilingual education model and translanguaging practices at public schools in Pereira, Colombia. Both studies revealed that the implementation of a CLIL model was beneficial to both students and teachers. Additional studies have focused on CLIL in mathematics and science courses. Leal (2016) focused on assessment in CLIL by analyzing test development for content and language in a natural science class at a primary school in Bogotá, Colombia. Sarmiento Salamanca and Pinilla Jiménez (2016) revealed that a CLIL approach was indeed an ideal match for their science class, as a means to promote spoken proficiency in young learners, where learners improved speaking fluency, increased awareness of language knowledge and use. And finally, Noriega and Zambrano (2011) identified the types of scaffolding and instruction used by mathematics teachers at a bilingual school in Santa Marta, Colombia, when teaching first-graders. They discovered that a range of visual aids, as well as the use of the L1 could be used to support the simultaneous development of content and linguistics competences.

CLIL Teacher Training and CLIL Initiatives in Colombia

The rise of bilingual education in Colombia and the increased desire to combine content and language, a CLIL-oriented approach has continued to emerge throughout Colombia in recent years. However, this increase comes at a cost, in which there is a growing need to prepare teachers as they are a key component for the success and effectiveness of bilingual, multilingual, and CLIL programs. There are many actors involved, both formally and informally, in ensuring that both in-service and pre-service teachers are equipped to face the challenges of today’s educational demands (Cuesta Medina et al., 2017; Tengku Ariffin, Bush, & Nordin, 2018).

Despite its growing popularity, to date there is no concrete data on the current state of CLIL in Colombia, the number of schools and teachers following the approach, the ways in which CLIL teachers are delivering their lessons or the results of these activities. According to Rodríguez Bonces, (2011), it is rare for universities in Colombia to offer bilingual teacher preparation programs, which are different from the language courses offered to pre-service or in-service teachers. But there are a few that have begun to include CLIL in their graduate and postgraduate programming. Additionally, there are online teacher training programs, such as the CLIL Essentials course offered by the British Council and graduate-level professional development programs, such as The CLIL Approach to Teaching, delivered both online and face to face by Universidad de La Sabana. Some context-specific CLIL initiatives have also been taking place in Colombia. They include The Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning (la CLIL) and the CLIL Symposium, both launched in 2008. However, Otálora (2009) mentioned that there is a great need to support PreK-11 and tertiary teachers in learning and implementing successful CLIL instructional strategies to ensure academic success through the use of English, because, for this type of content teaching to be effective, pedagogical considerations are required that allow instructors to overcome all potential language barriers arising throughout the instructional process.

Designing CLIL training programs is not an easy task, because CLIL and bilingual education are not interchangeable, even though they share similarities. According to Navés and Muñoz (1999), these shared characteristics include: respect and support for the learner’s first language and culture; competent bilingual teachers; mainstream (not pull-out) optional courses; long-term, stable programs and teaching staff; parent support for the program; cooperation and leadership of educational authorities, administrators, and teachers; dually qualified teachers in content and language; availability of quality CLIL teaching materials (Banegas, 2016); and properly implemented CLIL methodology. Therefore, there is a need for traditional training courses, conferences, reading professional journals, etc., whose sufficiency has been debated recently (Birman, Desimone, Porter, Garet, & Yoon, 2000; Darling-Hammond, 1998), to promote an understanding of CLIL principles, so that teachers working with CLIL can be adequately supported in their effort to deliver effective, quality CLIL programs (Costa & D’Angelo, 2011).

Method

For the purpose of this study a mixed-methods approach, gathering qualitative and quantitative data (Creswell, 2014) was used to investigate the perceptions and knowledge on CLIL and bilingual education. The following section will provide information on data collection instruments, context, and participants, of this research.

Data Collection

Quantitative data were collected from questionnaires and exams, while qualitative data were gathered from the open-ended questions of the surveys. Surveys are suitable for small-scale studies (Cohen & Manion, 2000), and are a valid and reliable source for collecting data because they make it simpler and more understandable, and it is easier to obtain complete answers (Tanur, 1992) from respondents. Furthermore, surveys are especially well suited for asking factual questions, behavioral questions, and attitudinal questions (Dörnyei & Taguchi, 2009). Due to the small population in this study, its researchers decided to use simple computer-assisted data analysis software in accordance with Ose (2016). Microsoft Excel was a suitable tool for coding and structuring answers to open-ended questions. All texts from the open-ended questions were transferred into Excel, and functions within the program were used to organize the data for coding. Then data were then cross-referenced and sorted so that generalizations could be made where possible, and subsequently categorized. This study also included the action research approach (Mason, 2010), exploring and analyzing what teachers do better and thus making it possible to identify gaps and perceive problems related to teaching, learning, and the curriculum.

Three instruments (two questionnaires, one achievement test) were utilized to collect data throughout the three stages of this study. They were delivered to the participants in person by one of the two researchers. The achievement test and the questionnaires were completed by hand following the school administrator’s instructions. Data were first gathered through an initial questionnaire administered to 26 participants at the initial meeting, before the teacher development program started. The second and third instruments were administered to participants at the end of the course. Data from the instruments were collected and fed into an Excel file from which dynamic tables and graphs were produced for further analysis.

The data obtained throughout the three stages of the study allowed researchers to find out if any changes occurred in teachers’ perceptions and or knowledge toward teaching curricular subjects in English following a CLIL approach during and after the training program, and if these findings matched the results gathered from the achievement test.

Context

The school in this study is a large private co-educational school from Transition to 11th Grade in the city of Valledupar, Colombia. At the time of the study in 2015-2016, it had more than 1,200 students, and the population it served was made up of mainly lower middle- and middle-class families. Prior to the study, the institution had started to migrate from EFL to content-based instruction (CBI) over a period of 2 years prior to the study in its effort to become a national bilingual school. During the study, which lasted 9 months, the school increased the number of weekly English instruction hours from three to six, hired a specialist to help teachers transition from a traditional EFL approach to a bilingual one, and the teaching of nonlinguistic subjects in the target language was approved.

Participants

Twenty-six teachers selected by school administrators participated in this project to become CLIL trainees. The group consisted of eight MEN and eighteen women, 15 were aged between 21 and 30, the others between 31 and 40. All participants possessed language teaching degrees and had similar ethnic and educational backgrounds. Their English language proficiency levels ranged from A2 to B2 within the CEFR. All participants were Colombians. Their English teaching experience varied from two to 10 years, averaging five. Half of the teachers taught children under 10 years of age (mainly Grades 2 to 4) and the remaining taught students in lower secondary school (Grades 6 to 8) and upper secondary (Grades 9 to 11) , and all of them were teaching different subjects through English such as math, social studies, chemistry, history, art, and language arts. Before the research project started, all participants were informed about the study and its procedures, and all of them signed a letter of consent. The teachers were selected because they were either English teachers or teaching subjects through English.

Data Analysis

The collected qualitative data were analyzed using the grounded theory approach (Corbin & Strauss, 2008), triangulating the data collected. Quantitative data were analyzed with descriptive statistics in this case frequency counts (Creswell, 2014), which were used to help describe basic elements in the data, create summaries, and conduct simple analyses of the data. Due to the small population, researchers decided to use simple computer-assisted data analysis software.

The Course

To deliver the course, an approach using information and communication technologies was utilized. The Fronter Education (LMS) was selected as the fundamental tool for hosting all the teaching and learning material, giving the instructor (one of the researchers) and the trainees the ability to participate in forums, download and upload materials, conduct real-time online classes and chats, and record live class sessions. The real-time class sessions provided participants with a similar experience to face-to-face sessions, where learners could interact with each other and questions were answered in real-time. The webcams helped participants to engage in natural interaction and form closeness patterns.

The training course comprised a 60-hour training program with seven two-hour online sessions on Fridays; forty-two hours of autonomous learning in which reading of the assigned documents and participation in the mandatory discussion forums; a two-hour face-to-face question and answer session; and a two-hour session at the end of the program in which trainees took the CLIL achievement test and completed the CLIL evaluation survey.

The online courses were different from the face-to-face sessions in that the instructors started each face-to-face session with learners interacting and making connections based on the previous session(s). Another difference was that the assigned module hosts lead group discussions for the first 10 minutes of each session. This allowed participants to be more active as participants in the online portion of the course as well as take on leadership roles within the online environment. Furthermore, the closing of the online sessions was centered around fat questions, which are open-ended questions that require thoughtful, multiword answers, as seen in the examples below. These types of questions engage learners in generating discussion from different angles of the session, allowing them to use more of their higher-order thinking skills. Examples of fat questions include the following:

Give three reasons why . . .

Explain why . . .

Why do you think . . .

In what ways are ___ and ___ different or alike?

Predict what would happen if . . .

This line of questioning helps the online learners to verify and check into what has been learned, allows them to share their opinions about the session, and encourages creative thought.

Communication is considered to be a key aspect of online learning, especially between instructors and students because of its role in learning effectiveness (Soffer, Kahan, & Livne, 2017). Therefore, the researchers in this study were keen on providing the participating in-service teachers with successful teaching models as well as examples of how to decrease teacher-talk-time (TTT) and increase student-talk-time (STT), which is essential in teacher training programs, especially if they are delivered online. Communication strategies were discussed at the beginning of the online course so that learners were aware of what was expected of them from the beginning, which is in line with Bristol (2019, p. 72) who claims that “policy can go a long way at keeping the online community headed in a positive direction” (p. 72).

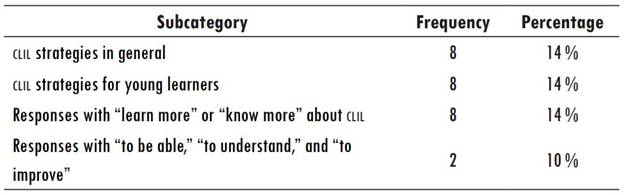

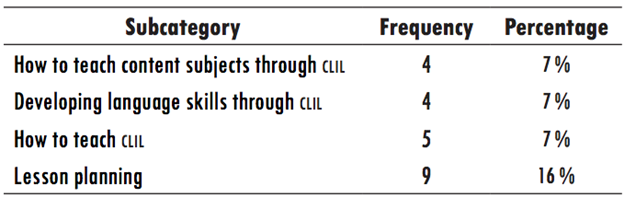

The open-ended questions from the questionnaire on teachers’ attitudes, perceptions, and experiences in CLIL generated a total of 59 written items out of 78 expected items if all 26 participants had responded to the question with the full number of items requested in the question. The question stated, “Write three things you would like to learn or learn more about, be able to do or be able to do better at the end of this session.” The results helped the researchers collect information about the training that teachers expected to receive. Data collected was fed into an Excel file and categorized into three groups: CLIL strategies and fundamental CLIL concepts, CLIL implementation and lesson planning, and CLIL subject knowledge and methodology as seen in Table 1.

Results

The following sections will provide insights into the participants perceptions and experiences regarding CLIL-oriented strategies. More specifically, the results surrounding CLIL teacher expectations, which occur before the actual design of the development program, where findings are reported based on their perceptions of training needs before the CLIL training and the last sections will highlight their perceptions about the training program.

Teachers’ Perceptions of Their Training Needs Prior to the CLIL Development Program

The results of the study revealed that all the teachers that participated in the study mainly thought of the approach to improve language and did not see CLIL as an approach to education. However, it is interesting to observe that the study found that 34 % of the participants were conscious of their training needs and aware that they required more content knowledge to improve their teaching practice. These needs had to do with time for lesson planning and availability of teaching resources which are further developed below.

CLIL Teacher Training Expectations Before the Development Program

Responses referring to CLIL teachers’ training expectations before the development program provided the significant input as to the design of the course, since the course was designed specifically for this population. More than half of the participants (51 %) felt as if they needed additional training on the CLIL strategies and fundamental concepts of CLIL. They also expressed a desire for the course content to be directed towards implementation and lesson planning (37 %). These course expectations as shown in Table 1, were essential in designing the CLIL development program, but also played a key role in participants’ interest and enthusiasm throughout the training process, because they were empowered by participating in the selection of the course content.

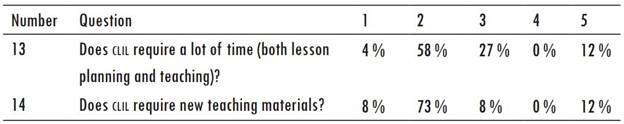

Time Devoted to Lesson Planning

Teachers were concerned and worried about time, with 62 % agreeing that CLIL is time-consuming for lesson planning and teaching. This was cross-referenced with semi-structured interviews held with participants, teachers, and coordinators. They all mentioned that more time and training was needed to plan lessons carefully so students could assimilate the topics. Subject area coordinators (math, sciences, humanities, English) further expressed that by not having prior training in CLIL and bilingualism processes, they felt that they lacked the know-how to support their teachers. In this sense, time for lesson planning was an important aspect to bear in mind from the participants’ perspective when implementing CLIL, as shown in Table 2.

Local Availability of CLIL Teaching Materials Locally

In semi-structured interviews, the participants stated that the textbooks they were using to teach math, science, and social studies were difficult to use for students and teachers due to the length and the higher English level, as if considerations on the students’ EFL context were nonexistent. As a result of the textbook not being an ideal or even a close match to the learners’ linguistic level, teachers needed additional skills to successfully adapt the materials to their context. Therefore, lack of training to use these resources (textbooks and supplementary materials included) in turn hindered students’ comprehension of the concepts. This means that if the teachers were aware of the importance of establishing both content and language goals separately, along with knowledge about how to successfully teach and assess content, using English as a vehicular language, academic results would have been more successful. The materials that were being used claimed to be suitable for ELLS. However, once the researchers evaluated the materials they advised the school to contact the publisher, so the school and the publishing house could work together to choose the best route to take to adopt the newly acquired textbook series that matched the needs of both the students and teachers. This is a classic case where a textbook series was chosen because it claimed to be the best academic solution on the market, but not aligned realistically for the students in question, and too much for the teachers to handle. Results from the questionnaire revealed that 81% agreed that new teaching materials were needed for them to implement CLIL successfully (Table 2).

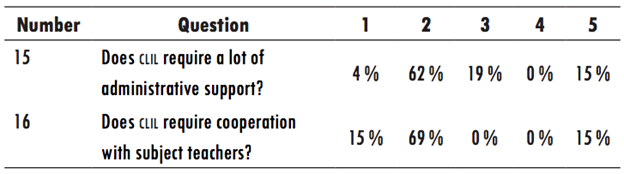

Administrative support, teamwork, and cooperation

With regards to administrative support, teamwork, and cooperation among teachers, 66% of the participants responded that they believed they would need more support from their coordinators and subject specialists to work with the new CLIL teaching paradigm, which would require a lot of administrative support as shown in Table 3. Additionally, throughout the training sessions, teachers mentioned verbally through semi-structured interviews a lack of appropriate support to carry out CLIL and bilingual processes. Participants expressed the need for working together when planning CLIL lessons and carrying out class observation protocols to mentor teachers on their way to successful CLIL lesson delivery. Most teachers agreed (84%) that CLIL requires teamwork and there was a lack of time to plan together and that a teamwork scheme had not been adopted by the school yet. Therefore, teamwork and administrative support were crucial factors that needed to be addressed to successfully implement a CLIL approach.

CLIL Strategies and Fundamental Concepts

The two largest sets of responses, making up 30 out of the 59, came under the categories of CLIL strategies (28 %) and fundamental CLIL concepts (24 %). In respect to CLIL strategies, 50 % of the responses in this category referred to a teacher’s interest in learning CLIL strategies for young learners, and the rest of the responses focused on teacher training needs regarding strategies in general, as shown in Table 4. This finding, teacher’s interest in learning about CLIL, is not surprising since 69 % of the trainees taught children under 12 years of age. Several responses indicated that more teacher training efforts should incorporate strategies, “I would like to learn strategies for teaching young learners,”(Participant A), or “to learn different strategies to teach different subjects” (Participant J), and “I would like to learn about strategies to assess the process”(Participant F).

On another note, teachers also expressed their desire to know more about CLIL, in which fourteen out of the 59 responses (24 %) fell into the category of fundamental CLIL concepts, such as “How to improve English language teaching with CLIL” (Participant A) or “I would like to learn more about CLIL,” (Participant G) and “I want to be able to un-derstand what CLIL is,” and “I want to be able to understand what CLIL is,” (Participant L). This is a clear indication that although participants were all content-based teachers, they started to realize that they lacked the necessary competences and overall knowledge about a CLIL-oriented solution. When the participating teachers started the teacher training sessions, they had little acquaintance with the CLIL approach. Therefore, their limited phraseology when describing their training needs to improve their CLIL competency can be considered a reflection of the need for a development program to help them attain the competencies needed to teach under the CLIL approach.

CLIL Implementation and Lesson Planning

The second two largest sets of responses after CLIL strategies and CLIL fundamentals, corresponding to 37% out of the 59 responses, were categorized under CLIL implementation and lesson planning. Twenty-one percent of the responses showed that teachers were concerned about the implementation of CLIL in general, using CLIL resources, teaching content subjects through CLIL, and developing language skills, as seen in Table 5. The remaining category (16%) showed teachers’ interest in lesson planning, as shown in Table 5.

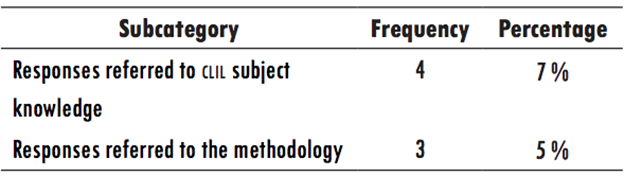

CLIL Subject Knowledge and Methodology

The third set of responses, 12% out of the 59, were categorized as CLIL subject knowledge and methodology, as shown in Table 6. Few responses (7%), showed teachers’ interest in learning more about subject content, while even less (5%) mentioned teachers’ interest in methodology.

The results of the data gathered before the development program began suggesting that, though the experience of teaching through English had been positive for them, the teachers in this school had been teaching non-linguistic subjects in English without having proper prior training to do so. This lack of training attest to their acquaintance with CLIL and bilingual education were at a basic level, and their training needs and expectations were centered on learning the fundamentals of the approach, the strategies they needed to teach content through English, and the methodology and lesson planning they required to deliver lessons where content and language were integrated. Bearing these results in mind, it is safe to say that these teachers needed formal teacher training to equip them with the fundamentals of a CLIL approach so as to have sufficient knowledge to integrate content and language, thus improving their teaching skills and becoming successful CLIL practitioners.

Teachers’ perceptions about the CLIL training program

In the first stage of this study, almost all the teachers perceived that CLIL was beneficial for English Language Learners (97 %). Upon completion of the course, this perception did not change. Moreover, teachers could describe the aims of the approach and its underlying theories, principles, and outcomes. A considerable number of participants believed they understood the principles and fundamentals of CLIL (73 %). In addition to this, nearly all teachers (91 %) responded that they strongly agreed or agreed on understanding the potential benefits of this approach.

However, these outcomes contrast with the findings gathered from the CLIL Essentials Achievement Test, which gave researchers insights regarding how acquainted the teachers became with the concepts taught in the training course. Results from the test showed that only 31 % of the teachers had a clear understanding of the definition of CLIL, more than half had doubts regarding scaffolding and operating factors for CLIL implementation (54 %), and 62 % did not have a clear understanding of content, culture, or cognition. In addition, varying but significant portions of the participants still struggled with Cummins’s (Cummins, 2009; Halbach, 2012) concepts of basic interpersonal communication skills (23 %), and cognitive academic language proficiency (77 %).

According to results from the CLIL Essentials Achievement Test, all the teachers appeared to know what the 4 Cs stand for, over three quarters knew the difference between CLIL and traditional EFL teaching (77 %), more than half understood what content is (62 %), and most knew the concept of the language triptych (72 %). However, when teachers were evaluated on completing a CLIL lesson planning template, more than half were not able to clearly explain the instruments and criteria they would use for assessment (69 %); almost half did not have a clear understanding of how to describe lesson content (46 %); more than half struggled with designing tasks and resources to promote cognition and cultural awareness (65 %); nearly three quarters strived to design communicative tasks to develop language of learning, for learning, and through learning (74 %); and 54 % did not show a clear understanding of how to establish learning goals and learning outcomes. Additionally, throughout the training sessions, teachers frequently asked questions about how to integrate content and language and how to sequence activities so that linguistic and cognitive demand would be at the right level. The results revealed that teachers still require further teacher training on Cummins’s matrix (Cummins & Swain, 1986) and lesson planning to design CLIL lessons. Yet, 73 % of the participants thought they could transfer the principles they learned into practice when lesson planning as a result of the CLIL training development program.

Regarding CLIL implementation and strategies, participants revealed that the training courses were useful, making them aware that lesson planning and learning strategies in this approach are different when compared to EFL, CBI, and Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL). Moreover, even though their repertoire of strategies increased throughout the training, the twenty-six participating teachers said they wanted more training on strategies in future development programs.

In relation to CLIL fundamentals, despite the fact that teachers found the training useful in this matter, they still expressed doubts when referring to the language triptych, which is a conceptual tool put forward by (Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010) that helps teachers and learners identify three types of language needed for effective CLIL: language of learning (language related to understanding the subject), language for learning (functional language for carrying out learning tasks), and language through learning (new language likely to arise according to individual learner needs during this process). The triptych allows teachers to understand the linguistic progression in CLIL and supports teachers in helping students to use a new language rather than learning vocabulary in isolation. Given the results here, those from the CLIL achievement test, and their comparison with stage one, it is safe to conclude that participants still need lots of support and coaching to understand CLIL fundamentals.

Discussion and Conclusions

Results here resemble findings from another research carried out in Colombia and Europe. In Colombia McDougald (2015) found that 61 % of the participants teaching content areas in English knew little about CLIL. Massler (2012), in Germany, observed that almost none of the primary state school teachers in her study had CLIL training or CLIL teaching experience before joining the project. However, in this study, most of the respondents (81 %) said they had already taught content areas through English, and 92 % said they had positive experiences teaching content areas through English. More than half of the teachers said they did not need to be more knowledgeable on the subject they taught. This response from 92% of the teachers that participated can be attested to their experience gained teaching content area subjects, where participants expressed having enough experience and skills to teach content through English. All of participants have been teaching math, science or social studies in English, despite being unknowledgeable about CLIL or how to effectively comply with content objectives and realizing themselves that they did not have enough experience and know-how in the nonlinguistic subjects they were teaching. These findings are similar to the study conducted by Navés and Muñoz (1999), who found that CLIL teachers are often competent in the foreign language but have no specific training in the content subject they teach. Although teachers are confident in teaching English, it was revealed that they were not aware of the variables (content of lesson planning, adaptability of resources, knowledge of non-linguistic subjects, a support system and understanding that a CLIL approach in context oriented) that cater to the success of combining content and language.

As lesson planning was found to be an area that participants struggled the most with, Echevarria, Vogt, and Short (2016) argued, that proper planning is imperative, and it could be the hardest facet of good teaching methods to learn, and there is a risk that it can become a shot in the dark if there is no sustainable mentoring program and reliable team support. CLIL teachers should be able to produce lesson plans and organize lessons according to cognitive demands, which require additional time to plan (Banegas, 2015; Pavesi, Bertocchi, Hofmannová, & Kazianka, 2001). In short, lesson planning requires time, but also requires institutions to allot time for teachers to plan and collaborate accordingly for the successfully teaching and learning process.

CLIL teaching materials are seldom available in Colombia, and schools using English as the vehicle to learn often use textbooks from international publishers (Curtis, 2012; Torres-Rincon & Cuesta-Medina, 2019). Most of these textbook series have been designed for English language learners (ELLS) who live in countries like the United States or the United Kingdom; as such these materials often fail to meet students and teachers’ needs according to their context.

Facts and data in this study demonstrate that, with the advent of CLIL and bilingual education in Colombia, some institutions have incorporated approaches and/or curricula without analyzing operating factors or the scale of their CLIL program, even though they are key issues when implementing CLIL. These operating factors include, teacher and student target language fluency, time devoted to teaching/instruction, nature of delivery for content and language, and even assessment procedures. In order to effectively address these operating factors, educational institutions should ensure teacher´s availability, assess their level of English, their expertise in teaching the target language and the content subjects, and their willingness to move toward new teaching paradigms. Additionally, the amount of exposure to the vehicular language and the way the target language is used should be discussed, including assessment. Data from this study suggests that teachers were not aware of how to teach their subjects in English, they lacked target language fluency, and there was no time allotted for lesson planning, or even to collaborate or share with peers.

Nevertheless, the small-scale of this research project can be characterized as a case study, so its findings should not be generalized. It is difficult from overall CLIL research that has been conducted across Colombia to draw conclusions due to the complexities of investigating learning in the contexts in which it occurs. One size does not fit all, and there is no one single model for CLIL, because it depends on the educational setting and other unique associated features (Coyle et al., 2010). Furthermore, the timeframe for this study could have been more extensive to produce observable changes in teachers’ attitudes, perceptions, and competencies. The suggestion is for future studies to carry out longitudinal research within a period of at least an academic school year to better evaluate the process and collect more data. Nonetheless, the study is useful in the sense that it can generate hypotheses that can later be tested and compared with other former, current, and future research.

The results show that teachers’ knowledge of CLIL is scarce among the participants who have not had formal training on this approach or done research on this field on a personal level, despite ongoing context-specific CLIL initiatives that have been taking place nationwide. Another surprising aspect revealed by the study is that teachers are teaching nonlinguistic subjects through English despite their lack of knowledge on integrating content and language and the absence of adequate ongoing training to implement a bilingual scheme in the school. Teachers are the main actors of change in education where they have a pivotal role in the implementation of CLIL. Therefore, teacher training, stakeholder responsibilities, and professional learning communities on combining language and content should be at the forefront of academic discussions in Colombia. Considering the aforementioned, the current offer of teacher training programs to support institutions and teachers who embark on bilingual education and CLIL in Colombia is still insufficient. Consequently, teachers do not have enough or adequate methodological knowledge to meet the challenge of successful CLIL practice. To meet these needs, it would be beneficial if undergraduate and graduate programs in English language teaching and bilingual education included CLIL in their curricula, so that pre-service teachers be provided with theoretical and practical aspects of CLIL that would better prepare them to be potential agents of positive change and to gain positive, sustainable results in bilingual education and CLIL.

The study also revealed that theoretical aspects and factual knowledge on CLIL did not translate into practical understanding, as was revealed with the poor results obtained from trainees when asked to create a CLIL lesson plan in the CLIL Essentials Achievement Test. This may have occurred because actual CLIL practice in class, class observation, coaching, reflective teaching, and self-directed learning did not take place during this development program due to time constraints. Hence, it did not follow what previous research found: that new knowledge learned in teacher training courses should be used in the classroom, as new teaching competencies can only be acquired in practice (Hargreaves Roy, 1997).

Another issue that should be considered which may have affected transfer is the fact that the training course was delivered online, with only one face-to-face session at the end. Some studies have shown that online teaching has a negative impact on learner performance (Barker & Wendel, 2001; Nathan & Scobell, 2012; Owino, 2013). But the original purpose of this study was not to evaluate how the course was delivered nor its relationship to transfer, absenteeism, or other related issues. This said, the results do reveal a likelihood that the adopted scheme may have affected the retention rate because attrition was higher than expected. For further studies, when teacher development programs are being designed, it is suggested that it be mandatory to analyze the context in which the course will take place and carry out a thorough needs analysis before any action is taken (Butler, 2005; Ruiz-Garrido & Gómez, 2009).

Considering the above, it is safe to say that the key to future growth and sustainability of CLIL lies in well-grounded teacher education and ongoing evaluation procedures together with reflective teaching and quality assurance to help avoid paying lip service to CLIL principles and nothing more. This is something that should be seriously considered because the number of bilingual educational institutions claiming to use a CLIL approach is set to rise in Colombia, and the practice of using the term “CLIL” as a catch-all phrase or as a cliché in bilingual scenarios is likely to rise. As a result, quality CLIL could be affected, leading to poor CLIL practices resulting from teachers who are not sufficiently prepared to implement the approach in their classrooms. Coyle et al. (2010) said, “Poor quality CLIL could contribute to a lost generation of young people’s learning” (Coyle et al., 2010, p. 161). To reduce bad quality, Hargreaves (2003) suggests that practitioners join forces and establish a local teacher-led CLIL learning community, which can also join other learning communities worldwide. This would allow teachers to engage in meaningful collaboration and share successes, problems, and challenges, supporting each other and constructing local knowledge and understandings. As Coyle et al. (2010) argue, there is a shared belief that, for CLIL theories to guide practitioners, they must be “owned” by the community, developed through classroom exploration and understood in situ theories of practice developed for practice through practice.

Colombia has struggled to improve the English teaching-learning process, and its endeavors have led to the development of diverse projects, including some involving CLIL. CLIL has been included as one of the suggested approaches launched by the Colombian MEN, but a framework to structure and assess the quality of CLIL practices in Colombia has yet to be created. A formal framework to guide educational organizations to structure and assess teacher training courses including a theoretical framework, effective evaluations and procedures should be the target of future research.

Although the results of this study cannot be considered representative of the situation of CLIL in Colombia, the results of this research are useful when one is thinking of implementing CLIL training programs and carrying out strategies to improve the CLIL State of the Art project in each context, including quality and practice. It is important to collect ongoing feedback on a regular basis from teachers, researchers, and educational stakeholders involved in bilingual scenarios to analyze how the needs of the teachers evolve as they have more exposure to teaching nonlinguistic subjects through English. Additionally, it is crucial to find out if the training programs held have met professionals’ expectations and are in line with new teacher demands. Moreover, more studies should be held to find out if continuous teacher development programs help teachers to both feel and be better equipped when planning and delivering content lessons through the target language. This would greatly assist the identification of future lines for teacher training and research.