Introduction

According to the British Council (2015), “English language learners tend to attribute strong English proficiency to practice and exposure to English speaking media, while low proficiency is blamed on a lack of practice” (p. 8). This situation was evident in a local private university in Neiva Colombia where the present study was conducted. In the first academic semester of the year 2015, a community visit, a Likert scale survey, and informal talks were used to identify that the problem that most affected students was the lack of opportunities to interact in English. Students claimed to lack opportunities to interact in English both inside and outside the classroom. For this reason, the focus of this study was to explore the impact of Skype as a complementary computer-mediated communication (CMC) tool to foster oral production. Six pedagogical interventions were designed and implemented to identify the aspects of oral production that are affected by the implementation of Skype sessions outside the classroom setting.

In addition, the course textbook presents some exercises that simulate real life conversations and attempt to foster oral production, yet through observations and informal talks with the head English teacher and students, it was found that in most of cases learners did not find those exercises neither meaningful, nor engaging. It was also evidenced that the students just worked on learning dialogues by heart and oral production was limited to repeating what the conversation in the textbook said without reflecting upon what they were saying. Moreover, students were not required to create their own dialogues where personal information or ideas could be incorporated. For those reasons, students emphasized that those activities did not make a significant contribution to the development of their oral production and claimed that the time for oral practice in the classroom was not enough to cope with all the other skills in just four hours per week.

Another factor that affected the situation was the students’ belief that the classroom was the only place where they could practice what they learned and interact with others using English. Added to the previous factors, students mentioned other limitations such as lack of time, opportunities, and strategies to practice the language orally both in and out of the classroom.

From our initial analysis, it was evident that more opportunities to practice English orally out of the classroom were needed. After a discussion between the researchers and the thesis advisor about possible alternatives to approach the situation, Skype appeared as an excellent alternative due to its multiple advantages including real-time communication through video, text, and voice, and its friendly use and easy access to get in touch with people anywhere in the world. With this in mind, we posed the following research question: What are the effects of using Skype sessions out of the EFL classroom on the oral production of a group of EFL learners in a private university? The main purpose was to identify the aspects of oral production that are affected by the implementation of Skype beyond the EFL classroom.

As a result of our study, it was also our intention to widen the perspective most teachers and students have about Skype as a tool just for communication as, due to this belief, many teachers and students are unaware of its potential benefits for academic purposes.

Literature Review

Once the research problem was stated, we were aware of the need to find alternatives to take the oral practice of the language outside the classroom. In this regard, there were several ideas which involved the use of technology, as it carries a high level of significance and motivation for learners. While exploring the different alternatives involving technology that could help to mediate the research problem, another element that called our attention for being highly meaningful, accessible, and motivating was social networking. Among the different options Skype appeared as the best tool to explore alternatives to deal with the problem as it facilitates face-to-face synchronous communication. Skype is one of the most important VoIPs (Voice Over Internet Protocols) that allows users to share files and simultaneously establish a videoconference with up to nine people. This software has gained popularity as a tool for language learning and teaching among users because of its low cost in comparison to other alternatives to learning English. Broadly speaking, Skype has revolutionized modern global communications “by making it simple for anyone with an Internet connection to make and receive superior quality phone calls for free” (http://about.skype.com/2005/08).

Since the moment Skype appeared, there have been various studies examining its impact in ELT environments and its efficacy has been demonstrated. Doughty and Long (2003) , for example, assert that Skype lets students interrelate, change, and refine their input. Godwin-Jones (2005) highlights that one of the major benefits of Skype is that it provides “additional channels for oral communication” (p. 9). Meanwhile, Elia (2006) reports that:

Skype can be used for communicating and sharing files [and] as a tool to facilitate small group class projects or small discussion forums [where] language learners can have the opportunity to speak in real-time with people from a variety of different countries. (p. 272)

These statements, offered by authors who have dealt with interests similar to ours, made it clear that Skype was definitely the best alternative we could implement to offer students opportunities to practice and develop oral skills.

Skype in Language Learning

Elia (2006) conducted a study in which the impact of Skype when using ‘Mixxer’ was explored. Mixxer is a free non-profit website open to anyone looking to practice with a native speaker in exchange for help with their own. Once users are registered in this educational site, they can search for speaking partners to practice a language via Skype. The author highlights the potential benefits of Skype and invites people to continue exploring it as it “can be a convincing application to be widely supported, experimented, and its efficacy monitored in different language learning contexts” (p. 275).

Other studies have suggested the beneficial aspects that this software has for ELT. Tsukamoto, Nuspliger, and Sensaki (2009) implemented a series of Skype conferences in Japan with a high school in the United States. According to the participants’ communication, this method was seen as more real and the communicative exchanges via Skype were described as engaging, enjoyable, and realistic. Additionally, Wu, Marek, and Huang (2012) emphasize that overall instructional methodology supported in social media engages students in learning from an active attitude that promotes critical thinking and actual achievement. In addition, Cuestas (2013) conducted a small-scale study in a Catalan primary school in which an interactional activity using Skype as the main tool to teach was implemented. This author points out that using a synchronous digital tool affects the interactional activity of students as it has the ability to create a real necessity for learners to speak an L2. Coburn (2010) implemented an action research study that focused on teaching oral English online in Iran. The conclusions of the study offer very useful insights that were taken into account when planning and implementing our interventions. Coburn’s (2010) results made us aware of the importance of designing tasks that are appropriate to the student’s level of proficiency. It also suggests the need to take printed materials to the online conversations and to use varied tasks and more student-centered topics that also take into account the specific socio-cultural context and technical skills required. Those recommendations were important to our study as the topics and content for the video sessions were decided together with the students. The activities also took into account the topics and the students’ socio-cultural context in order to make the spoken interactions meaningful and interesting.

Implementing Skype in the classroom positively affects other specific areas. Taillefer and Muñoz-Luna (2013) for instance, conducted a Skype-mate language project which aimed at enhancing oral communication skills and cultural awareness of students learning English and Spanish as L2. Results showed that non-verbal communication was crucial to mutual understanding when L2 level was low. Also, participants with a higher level of proficiency explained cultural matters and made comments about them. The authors establish that “within such communicative complexity, discursive and cultural issues seem crucial and should be considered in the L2 teaching curriculum” (p. 260).

One of the factors that prevent EFL learners from using the language orally is anxiety as speaking a new language can be a rather stressing experience for many people. Being able to interact in a controlled space, with known people, while sitting behind a webcam in the comfort of one’s home are all factors that contribute to relieving the associated stress that speaking English can cause. Additionally, participants were not using the language as part of a lesson requirement or under the pressure of a grade.

The strongest support we found for using Skype as the cornerstone of our study came from Romaña (2014) whose study focused on determining:

The effect of Skype conference calls as a computer-mediated communication tool in promoting the speaking skill in adults out of the classroom settings. The findings deem Skype conference calls an influential CMC tool to promote EFL adult A1 learners’ speaking skill, especially for social interaction purposes and oral reinforcement of both language fluency and course contents out of classroom settings. (p. 4)

Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC) in Foreign Language Learning

CMC is originally described by December (1997) “as the process by which people create, exchange, and perceive information from telecommunication networks that facilitate encoding, transmitting, and decoding messages” (para. 3). Drawing on Warschauer’s (1996) work, CMC is related to positive results and positive effect on the field of language learning and allows communication with L2 native speakers and other learners of English without limitations in terms of space and time. Peterson (1997) claims that CMC fosters self-directed learning in a less threatening environment as compared to typical L2 settings as it does not discriminate students for their level of skills, background, and learning styles that can be different among learners. Chapelle (2003) states that taking CMC as a means of interaction allows learners to look for opportunities for input that are not given in a real and regular social conversation.

Social Networking

Barrow (2009) defines social networking as a way of “communicating with others through online communities” (p. 436). To Luo (2010) , social networking embraces a number of features such as shared users, shared connections, similar interfaces, and diverse connections with others. More recently, Foremski (2012) claims that Skype should definitely be counted as a social network because in Skype:

You can set a status ‘mood’ message, you can text message, use it as a group chat system, you can share files, photos, your computer screen. Plus, you can talk with people plus video calls, and set up videoconferences with several people. (para. 2)

Methodology

Action research (AR) methodology was selected for our study as we intended to overcome a problematic situation that affected the EFL learning of the students of one of the teacher-researchers. Additionally, it was possible to identify and address that specific problem through pedagogical actions that were implemented with the learners.

According to Kemmis and McTaggart (1982), there are five main benefits achieved through AR. First, teachers are able to think systematically about what happens in the classroom. Hence, a problem affecting language learning and teaching is identified. Second, teachers try to improve particular aspects of learning by applying an action plan based on the particular issue. Third, it is possible to assess the outcomes of the applied action to continue with the process for improvement purposes. Fourth, teachers are able to check complex conditions in a critical and practical way. Fifth, by acting and reflecting, it is intended to enrich classroom language practices through the implementation of a flexible methodology (pp. 16-17).

Richards and Farrell (2005) state that the following procedures must be followed while carrying out AR: planning, action, observation, and reflection. Hence, AR enables teachers to enhance the practices implemented during the whole process by putting into practice strategies and foresee the actions to apply in the future. With these ideas in mind, the methodological plan carried out by the researchers involved two action research cycles. In the action phase, there were six pedagogical interventions involving the use of videoconferences via Skype.

Context and Participants

The institution where the study was conducted is located in the city of Neiva, Colombia. This private university has several computer laboratories but none is suitable for practicing English as they lack pertinent software and hardware for that purpose. The modern languages department was recently created and four levels of English are offered, each one of 48 class hours per semester. The majority of the university population belongs to social strata 2, 3, and 4.

Initially, the proposal was presented to the group of 32 students and all of them participated in the Likert scale survey and informal talks. Afterwards, the teacher-researchers asked for volunteers for the study and four students agreed to participate. The ages of the participants (3 females and 1 male) ranged from 18 to 21 years. They belonged to social stratum 2 and had a basic command of the language except for one whose communicative competence was higher. They were all taking the first level of English when the study began. Participants were required to devote time to getting prepared, logging on to participate actively in the sessions, and writing some journal entries.

Instruments and Data Collection

Video-conference transcriptions, researchers’ field notes, and students’ journals were the instruments used in the pedagogical interventions to collect data. To keep record of audio and video, two extension software packages were used, namely, Pamela-for-Skype TM and ScreenFlow.

Transcriptions. All of the relevant information was collected and transcribed on a Word document and then analyzed in ATLAS.ti software which helped us to analyze what the teacher-researcher and students said. Chunks of speech and non-verbal actions were turned into codes to identify the aspects of oral production that were affected by the implementation of Skype sessions outside the classroom.

Field Notes. Field notes were written by the teacher-researchers after each pedagogical intervention based on the recordings of the sessions through Pamela and Screen Flow. The field notes analyzed both the teacher-researcher and students’ particularities of their performance (body language included). The objective of the field notes was to identify students and teachers’ actions and reactions in the Skype sessions in varied activities such as answering questions, showing agreement, describing pictures, and expressing opinions among others.

Journals. After each intervention session, participants were encouraged to write a journal entry whose main objective was to analyze how Skype affected the development of their oral ability outside the classroom.

The research cycles implemented

By applying the AR cycle proposed by Kemmis and McTaggart (1982) , the authors of this study intended to use Skype as a mediating tool within videoconference sessions to collect data and to examine its effects on the participants’ oral skills. The two AR cycles carried out along the study are described as follows:

First AR cycle

Plan. The teacher researcher chose the topics to be dealt with in the Skype sessions. Participants were informed in advance about the topic so they studied related vocabulary, prepared ideas, looked for relevant information, and revised pertinent grammar structures. Every lesson plan format followed the same structure shown below.

Action. In the action stage of the first AR cycle, three Skype videoconferences were implemented each lasting between 30 and 40 minutes. The teacher-researcher made sure that Skype and the recording software were working correctly. In order to activate background knowledge, questions related to the participants’ daily life were asked, and participants were assigned turns to answer the questions. While each student was talking, the others listened, waited for their turn, and afterwards questions were asked. Those questions were intended to confirm understanding and required clarification, while others were about grammar and vocabulary.

Appealing pictures and videos were used to ensure active participation in the sessions. Furthermore, provoking questions were asked

Figure 1 First page of a lesson plan implemented in the first AR cycle. The second page was structured as seen in Figure 2.

to keep participants focused. When words or expressions were not clear, the teacher-researcher used mimics or gestures to facilitate understanding. Sometimes, words and expressions were written in the texting area of the Skype window to provide additional assistance in comprehension and foster active participation.

Observation and reflection. Three main actions were taken. One of the teacher researchers observed the recordings to write the corresponding transcriptions. The teacher-researcher leading the sessions wrote field notes. Finally, the journal entries written by the participants were read and analyzed by the researchers. As a result, the following aspects were kept in mind for the second cycle:

Despite the fact that participants showed interest in the sessions, they felt that the topics were not very interesting because the teacher-researcher had chosen them. In addition, using pictures, videos, and gestures played a significant role in keeping participants focused. However, it was noticed that when students did not have prior knowledge about the topics, they avoided participating.

Some technical difficulties related to the computer literacy of students and limitations of the Internet connection in rural areas had not been foreseen. Some external interruptions (e.g., noise, people interrupting participants) in the places from where they logged in also affected the development of the sessions.

Second AR Cycle.

Plan. In the second cycle, some pedagogical actions were improved. In the planning stage, participants were empowered to decide on the topics for the next three sessions. In relation to aural and visual aids such as pictures and videos, it was pertinent to inform the participants in advance of the URL where they could find these aids. The improved plan can be seen below:

Action. In the revised plan, participants were given the opportunity to take the initiative to talk without assigning turns and more corrective feedback was given by the teacher-researcher. The use of attractive pictures and interesting videos was more prevalent. Thought provoking questions that led to discussion were employed in the three sessions. Mimics and gestures were more frequent to reduce the use of L1.

Observation and reflection. While some actions taken for improvement actually worked, others did not. Regarding the topics for the sessions, participants played an active role in the sessions although in some cases they lacked knowledge to express a wider variety of ideas. Corrective feedback, mimics, and gestures also played a major role to facilitate students’ improvement of grammar and vocabulary.

Data Analysis and Results

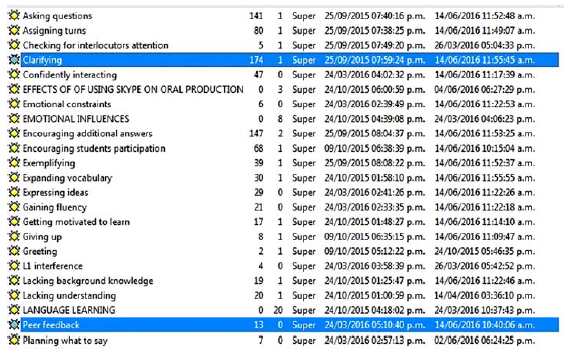

This section contains the qualitative analysis (through the use of the ATLAS.ti software) of the data gathered throughout the action research process. The data collection instruments were used to triangulate, validate, and verify the evidence and draw proper conclusions. A hermeneutic unit to codify information collected through the different

instruments was created. Codes were assigned in order to look for patterns and establish categories and sub-categories.

The core category that emerged from this research study was: Effects of using Skype on oral production. The emerging categories were: Language learning, Social Interaction, and Emotional Influences. These categories are discussed below.

Language Learning

This category shows that the use of Skype has a positive effect on language learning. First, students took advantage of the Skype sessions to clarify doubts about vocabulary and grammar structures. Second, they used Skype to practice pronunciation with the help of the teacher-researcher and peers. In this sense, feedback (subcategory) was relevant to help students to correct their mistakes.

I kept on making mistakes because I said things like “I am more lazier” but thanks to the session I was able to clear up the topics and remove my doubts.

(Excerpt 1. Student journal, student 2, October 9th 2015)

Elia (2006) concludes that “applications of technological advances have always found a direct use in language learning” (p. 265). In this sense, the excerpt above shows that using Skype affects learners positively in their pronunciation and grammar clarification, among others.

We could evidence that the more students are exposed to practicing the language via Skype, the more they learn new words, grammar rules, and even improve pronunciation. For the previous to occur, students need to be deeply involved, participate actively, and listen carefully to what their partners or instructor have to say. It would be pointless for a student just to be present in the session without taking an active and critical attitude towards what is being discussed. Consequently, engaged participants are more likely to use the language meaningfully for different purposes.

The following subcategories are associated with the language learning category: (a) expanding vocabulary, (b) gaining fluency, (c) feedback, and (d) body language.

Expanding Vocabulary

The participants in this study agreed that using Skype as a means of communication helped to expand their vocabulary.

One of the advantages of Skype sessions is that I can improve my vocabulary when speaking

(Excerpt 2, student journal 1, student 4, September 24th 2015)

This excerpt together with some students’ journals and transcripts support the idea that the Skype sessions have a positive influence on vocabulary expansion. Participants could enlarge and add a number of words they did not know before the study. Similarly, Wu, Marek, and Huang (2012) found that through the use of Skype sessions “students increased motivation, thought critically about the subjects discussed in class and improve their fluency, pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary and content knowledge” (p. 12).

We all have certain central topics in our conversations. When those topics are not familiar to us, there is not much to say and therefore we can become uninterested or even reluctant to participate. In this regard, participants were asked to discuss something they enjoyed to ensure they were engaged and motivated to talk. Nevertheless, motivation is an aspect that is really difficult to measure but some behaviors can give us an idea when students are eager or excited to practice the language.

Gaining Fluency

The participants in the study also agreed that through the use of Skype sessions they could increase their fluency throughout the whole process.

I think that this experience helped me a lot in terms of English use and because I can have a good performance in a dialogue and speak fluently.

(Excerpt 3, student journal, student 1, September 24th 2015)

This student’s journal sample supports that Skype influences participants’ oral production in the sense of gaining fluency. Similarly, Wu et al. (2012) concluded “that students thought critically about the subjects discussed in class, and improved their fluency” (p. 12). Regarding Wu et al.’s (2012) conclusion, this study also demonstrated that Skype may be a powerful tool to promote students’ fluency.

In line with these authors, it was satisfying to see how the participants made progress in their fluency. Nonetheless, it needs to be acknowledged that this was not only an isolated linguistic development but a result of establishing stronger bonds as a group. Progressively, students were able to organize their ideas faster. The progress was not only noticed by the researchers but also by themselves who felt proud. However, it would be weak to assure that participants are always able to express ideas with the same level of fluency. Too many external and internal factors can determine whether they speak fluently or not. The participants’ mood, the topic discussed, the technical difficulties, their health condition, and even the weather can affect their performance.

Feedback

In terms of feedback, learners expressed that there was an ongoing process of feedback, not only from the teacher, but also from their classmates.Romaña (2014) concludes that “learners also acknowledged that they used the Skype™ conference calls independently in order to help each other in the accomplishment of their own language learning activities and goals and their knowledge building experiences through an online environment” (p. 87).

As Figure 5 shows, the number of codes demonstrated how often feedback was given. In this sense, Ritchie and Bhatia (2009) assert that “learners today can contact a native speaker in any part of the world and receive highly individualized feedback in spoken and written language” (p. 547). In this particular case, even though there were no native speakers of English involved, feedback was meaningful as it was received in the context of oral exchanges about each individual’s performance.

It is important to acknowledge the role played by the instructor who was resourceful and creative in order to make himself clear when explaining something, responding to students’ doubts, or when giving relevant feedback as expected by the audience. It is sometimes necessary to be emphatic when making corrections to participants as they can easily get disengaged with the task via Skype. Then, finding the best way to keep them alert and offer feedback is a must depending on the particularities of the participants.

Participants who have difficulties to be concentrated need to be addressed properly to catch their attention at all times. It is also relevant to highlight how offering feedback can boost students’ learning but when this is not done in the right way, it may lower their self-esteem as learners.

Body Language

Regarding the outlined subcategory, Taillefer and Muñoz (2013) concluded that “non-verbal communication was key for mutual understanding when L2 level was low” (p. 263). In this sense, this study demonstrates that body language is a relevant non-verbal communication technique among students and teachers in order to make themselves understood when there is not another option as shown in Figure 6 above.

Undoubtedly, body language plays a major role in making one’s ideas clearer, but it is a strategy that needs to be carefully applied in ELT situations to have positive outcomes. If a word, phrase, or idea is reinforced through body language, students might remember it more easily. On the other hand, when those types of gestures are overused, they will not be seen as appealing and cannot have the same impact. Skype enables participants to communicate by gestures but taking into account the time constraints and the features of this synchronous tool. In order to practice the oral language, it is very important to use them in a balanced way.

Social Interaction

This category shows that through the use of Skype learners can reach social communication skills out of the classroom. Fitch and Sanders (2005) describe social interaction as a diverse and adaptable conjunction of interests that comprises speech analysis, pragmatics, discourse analysis, ethnography, and the subarea of social psychology called language and social psychology. The following excerpt taken from one of the learners’ journal shows what has been outlined above in the sense of social interaction since the student agrees that by listening to their peers it is possible to establish social spoken conventions.

Listening to my classmates, answering to them and interacting with them, we learn new ways to communicate.

(Excerpt 4, student journal, student 2, September 24th 2015)

Despite the fact that the four participants had known each other since the beginning of the study, their participation in the Skype sessions constituted an alternative space for meaningful interaction. From our perspective, through Skype it is possible to increase the interest in learning because as a group they are carrying out a social act that aims at attaining a shared goal. Also, it is clear that by having these meetings on a regular basis (weekly or monthly), participants may get into the habit of interacting in the foreign language that entails social interaction and makes them feel part of a social group. By doing so, they feel less limitations on expressing their ideas freely. In this sense, shyness might be lessened and there can be a greater desire to interact with each other.

Additionally, the category named Social Interaction has two emerging subcategories: Negotiation of meaning and Cooperative Language Learning.

Negotiation of meaning. With regards to this subcategory, this study gives evidence that students took Skype as a means of negotiating meaning. In this vein, Maslamani (2013) concludes that “Skype may provide learners with more opportunities for communicative interpersonal interaction that is rich in the meaningful negotiation of meaning” (p. 77). The following excerpt taken from the teacher researcher field notes in regards to negotiation of meaning:

Carmen had a misunderstanding because she thought the footballer Lionel Messi was the center of the conversation and she asked why not to talk about Michael Jordan. Then, the word Messy was clarified with simple examples as an adjective to use in making comparisons.

(Excerpt 5, teacher-researcher field note, October 5th 2015)

In this sense, we can state that the L2 participants were engaged in negotiation when there was a clear misinterpretation of words as shown in the excerpt presented.

Cooperative learning. In the context of this study, the Skype sessions were a significantly influential factor in making students work cooperatively. Some authors define cooperative learning (CL) as “the instructional use of small groups so that students’ work together to maximize their own and each other’s learning” (Johnson and Johnson, 2008 p. 5). Tran (2014) asserts that CL is organized and success-oriented for every single person that takes part in a cooperative learning group. To Koutselini (2008) , CL entails “the teaching and learning situation that ensures coherence and positive interdependence among members of small groups and results in learning for each member of the group” (p. 34). A research conducted by Nagel (2008) shows that CL is an “effective strategy that promotes a variety of positive, cognitive, affective, and social outcomes” (p. 364).

In Figure 7 below, there is evidence that they worked cooperatively when expressing ideas, giving feedback, asking for vocabulary, and exemplifying.

In this regard, Leonard (2012) concluded that “with the usage of collaboration and cooperation, retention efforts are aided because students are more motivated to remain in a class or program if they are receiving help from a group of their peers” (p. 39). In this sense, this study matches the authors’ conclusion since by working cooperatively the participants were co-constructing meanings and gaining fluency too as they felt comfortable talking to each other. Time availability and the motivation to be engaged in this process were also reflected in this subcategory as all the participants except one, completed the process satisfactorily.

Emotional influences. The data analysis unveiled students’ confidence when being praised orally by the teacher researcher. In this sense, Derks et al. (2007) concluded that emotional communication in online and face-to-face communication are surprisingly similar and that online communication even seems to reinforce rather than inhibit the expression of emotions. The following excerpt taken from a participant sheds light on the above mentioned subcategory.

What I liked the most about this session was that I was more fluent when speaking and less nervous

(Excerpt 6, student journal, student 1, May 13th 2016)

Derks et al. (2007) concluded that “we seem to survive pretty well in our social interactions and accompanying emotional expressions in CMC” (p. 16). In this regard, the data analysis unveiled that students felt confident when the teacher researcher praised them orally. It could also be noticed that participants were self-assigning a speaking turn which means that they were confident enough to communicate something to the teacher and their classmates.

In this category two emerging subcategories were identified: confidence and anxiety.

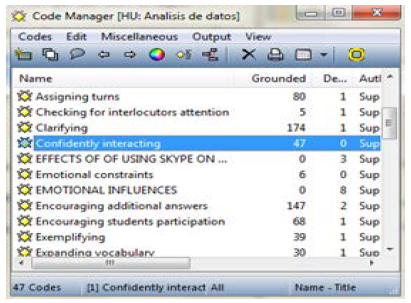

Confidence. This subcategory deals with how students can build a strong sense of feeling secure when speaking through an online platform (Skype). Figure 8 shows the highlighted subcategory and the number of times that confidence was mentioned by the students in their journal entries which at the same time provided support to the subcategory.

In the graph above, the high number of times that the code “confidently interacting” took place in the journal entries is demonstrated. This shows that students were aware of the fact that they were gradually gaining confidence. This positive aspect was evident when they interacted in the sessions and eventually expressed this perception in their journals. In this regard, positive social interactions, including student-to-student collaboration and student-teacher interaction, allow learners to change their knowledge grounds; thus, motivation, confidence and satisfaction are improved (Browstein, 2001).

In our point of view, confidence is not easily achieved just by interacting with others. An atmosphere of tranquility and mutual trust is a must. Feeling the pressure to speak a foreign language without making any mistakes can be a negative factor that hinders confidence in learners especially in the early stages. On the contrary, feeling at ease or in your comfort zone is the ideal setting for a Skype session. From the very beginning, it is important that the person leading the session makes the participants aware that taking the risk to speak is essential to develop oral skills. Making positive appraisals, scaffolding, and praising students constantly, among other strategies, can be helpful to create a relaxing environment to make participants feel that even the smallest contribution matters whether in a debate or a simple discussion.

Anxiety. This last subcategory shows a negative aspect in students’ personal emotions. Although this subcategory emerged in the diagnostic and first cycle of the pedagogical intervention, it was not found in the second cycle as the participants did not mention anything related to it in their subsequent journals.

I felt nervous in the session because I had never interacted in a direct way with other people before.

(Excerpt 7, student journal, student 1, September 24th 2015)

In this regards, Horwitz (2001) recognized anxiety as an emotive influence that could significantly affect

the learning process. Furthermore, according to Sheen (2008) , anxiety can interfere with L2 students’ ability to recognize feedback and hence reproduce it.

Opposite to the concept of confidence, anxiety can emerge even when there are positive relationships, attitudes, and behaviors between all the participants and the instructor. Certainly, anxiety can have a negative impact on the students’ performance which is understandable taking into account that some of these beginner participants have never faced similar situations in which they are expected to express ideas in a foreign language in front of their classmates and teacher. It is true that the level of anxiety can be lowered little by little as students gain more confidence day after day. The key element is to involve them in the Skype video sessions, in a meaningful, non-threatening way to reduce stress and avoid anxiety from taking control of students.

Conclusions

Our study explored the effects of using Skype sessions on oral production outside the EFL classroom. Once the research study was completed the following conclusions were drawn. Skype appears as a compensating tool for face-to-face lessons because students are exposed to the language they need to develop oral skills. This software positively impacts students’ emotions and develops better attitudes towards learning. Besides, working in groups promotes cooperative learning as students try to reach a common goal which is to improve their language skills.

Emotional bonds also emerge when students share the desire to learn. However, in order to engage students in the process, the topics for Skype sessions need to be carefully chosen, introduced, and led taking into account the different personalities of participants. A needs analysis is essential to ensure the selected topics are enjoyable, pertinent, and familiar for students, thus ensuring a student-centered lesson. As emphasized by Romaña (2014) and Wu et al. (2012) , proposing meaningful topics that students enjoy helps them to develop fluency. However, fluency should not be expected to emerge in this way and at the same pace for everybody.

Exploring new topics via Skype challenges students to learn and reinforce grammatical structures and vocabulary. However, it is worth remembering that the simple exposure to those structures and words does not guarantee their retention in students’ minds. Nevertheless, the relaxed atmosphere provided by Skype sessions fosters students’ confidence to ask for help and it is then when the teacher should take advantage of those moments to promote vocabulary comprehension and retention by using strategies such as mimics, gestures, and of course clear (written or oral) examples. It should also be acknowledged that using the mother tongue is valid to ensure comprehension when all the other strategies do not seem to work.

Another benefit of Skype sessions is that feedback is instantly provided and received and students can help to correct each other. Ritchie and Bhatia (2009) recognize that nowadays learners have access to individualized feedback through CMC practices. Teachers, however, need to be tactful in the way feedback is given so that students do not feel threatened, intimidated or embarrassed. When offering feedback, body language, gestures, and mimics help to remember, learn the meaning of new words, or understand sentences. On this matter, Taillefer and Muñoz (2013) find body language effective for beginners. Low-proficiency students appreciate the use of mimics and gestures as something enjoyable that helps them to understand the learning materials. Teachers are therefore expected to be very creative and expressive when giving feedback via Skype because a webcam usually captures the upper area of the body.

Skype sessions also help learners to develop social interaction and communication skills. Students feel positive when they can talk about their ambitions, wishes, plans, and opinions with their peers. It is relevant to bear in mind that CMC should involve meaningful activities where students can relate the topics to their daily lives and thus find a communicative purpose for their interactions. This conclusion aligns with Kern (1995) who states that though CMC is not the solution, it offers new classroom environments for social use of the language no matter that students are not in the physical classroom. Thanks to the small size of Skype groups, students have the opportunity to exchange ideas, learn cooperatively, and share their experiences and in that way negotiation of meaning emerges. Maslamani (2013) claims that Skype may provide students more opportunities for interpersonal interaction for promoting negotiation of meaning.

Expression of comfort and other emotional influences both positive and negative are indeed reinforced by Skype, though the way students express them can be very subtle. On that account, it is urgent to pay close attention and handle them appropriately in order to avoid negative emotions that may lead to demotivation. For this reason, an ambience of tranquility and confidence needs to be promoted.

Confidence arises when students present positive emotions and begin to take an active role in the conversation, e.g., by self-assigning turns. Brownstein (2001) lends support to this by asserting that student-to-student and student-teacher interactions allow learners to expand their knowledge which results in confidence gained. In contrast, anxiety caused by lack of preparation or familiarity with the topic can emerge as a drawback in the stages of Skype sessions and can inhibit effective learning. As such, it is crucial to promote positive attitudes towards learning and teachers are expected to stimulate a friendly ambience where students feel at ease.

Pedagogical Implications

In order to conduct studies involving Skype, it is necessary that all participants have basic background knowledge in the use of ICT tools. Furthermore, teachers and researchers need to select an adequate tool for oral skill development. Technical requirements such as the devices in which Skype is going to be used need to be taken into consideration since there are some that are not compatible with the software. The place where the sessions are going to take place must be suitable to avoid any kind of interruption. As suggested by Romaña (2014) , the number of participants should be limited since the less participants, the more personalized feedback is going to be given. Finally, the tasks to be implemented should be engaging, motivating, and different from those which are applied in regular classes in order to not only catch participants’ attention, but also to make them participate actively in the videoconference sessions.