Introduction

This action research describes the implementation of a meme-based strategy to increase English as a foreign language (EFL) vocabulary acquisition and retention in a Chilean classroom. It investigates the effects of an asynchronous action research work in which a group of young learners interacted with multimodal texts (memes), responding to activities as a means to increase high-frequency vocabulary in English. This research project was conducted in a primary school located in Concepción, Chile. The participants were 18 young learners from 6th grade.

The idea for this study arose from the review of several reports on the importance of the lexical dimension in the acquisition of English as a foreign language (Nation, 2001; Thornbury, 2004). Moreover, educational reforms in Chile in the area of English also point to and highlight the importance of this dimension at the primary levels of education (Barahona, 2016). In addition, young students live daily with virtual stimuli, mostly receive visual information, and are heavily influenced by their interaction through social media. In this sense, these students have developed ways of acquiring new information and ways of learning which can contribute to enhancing the process of learning a second language. Moreover, from a research perspective, young learners have important perspectives to contribute to EFL research, as they have transitioned from objects of research to social actors (Inostroza, 2018). In this way, this study aims to contribute with a strategy and methodology implemented in an intervention with young learners in order to help them acquire and retain vocabulary through the use of images and memes. It is also relevant to understand how children in Chile react to this type of intervention, as it is starting to be used in other countries (Kayali and Altuntaş, 2021).

Problem statement

In Chile, the teaching and learning of the English language are driven by economic and communication purposes, and the aim is to become a bilingual country (i.e., Spanish and English) (Glas, 2008). The methodology employed to this effect has shifted through the decades; teaching is currently context-oriented and seeks to make the learning experience more meaningful for students. In this sense, the role of vocabulary becomes crucial. As EFL becomes compulsory for all schools from 5th to 12th grade and more hours are added to primary school levels (Barahona, 2016), young learners have been put at the center of the discussion, given the positive implications of starting to learn English as early as possible (Inostroza, 2018).

Moreover, among some of the guidelines given by the Ministry of Education, vocabulary is presented as a relevant element in discourse; it is stated that students must master its use in both oral and written situations, as well as in listening and reading comprehension (Ministerio de Educación, 2012). It is also emphasized that learners should encounter new vocabulary in different contexts and use it several times in order to ensure acquisition. However, the reduced amount of time dedicated to the subject in school curricula has become a major hindrance (Barahona, 2016). Lexical competence then faces several drawbacks with regard to aiding the development of English language proficiency. According to Nation (2001), both teachers and learners should pay special attention and direct their efforts towards acquiring and retaining high-frequency words, as they make up the basis to comprehend day-to-day conversations and texts. Therefore, comprehension and the mastery of receptive and active skills depend strongly on this language component, which needs to become part of the key structure of lessons in Chilean classrooms.

Furthermore, there is a correlation between the number of hours imparted by school and grade and teachers’ proficiency level with the achievement of higher levels in the mastery of the language. Some studies have also dug into the other factors that can negatively impact language acquisition (Khasinah, 2014). Socio-economic inequalities, lack of funding, low level of competencies in teachers, and intrinsic motivation play a major role in developing language proficiency (OECD, 2012). In addition, another critical aspect that prevents vocabulary acquisition -and therefore the mastery of the language- is the lack of input received by Chilean students. As claimed by Krashen (1993), comprehensible input must be provided to learners in order for them to acquire vocabulary knowledge. Therefore, teachers should design methodologies and experiences that enhance the opportunities for students to acquire and retain vocabulary, considering the high relevance of the lexical dimension and the characteristics of young learners.

This study arises from the well-founded notion that young learners are at a crucial stage of their cognitive, affective, linguistic, and social development (Ozfidan and Burlbaw, 2019). Therefore, they need innovative methodologies that take these dimensions into account during their development. In this vein, a 6th-grade class of a school in the municipality of Concepción was chosen to implement a methodology that somehow overcomes the lack of encounters with important words, aiming for students to acquire greater fluency and knowledge of the English language.

This study was conceived in response to the problem regarding the lack of opportunities and instances for young students to encounter and learn new English words in contexts other than English class at school. The effectiveness of using multimodal texts (memes) in an asynchronous schedule to improve new lexical learning and retention was investigated. The action plan was executed in nine sessions, in which students received specially designed memes with high-frequency vocabulary for their level through the Google Classroom platform.

Conceptual framework

EFL in Chile and the role of vocabulary

EFL teaching in Chile has gained a lot of importance in recent years. Despite the efforts, standardized test results confirm that only one third of Chilean students can communicate at an elementary level (or A1-A2 as per the CEFR) after eight years of English classes at their schools (Barahona, 2016). As a compulsory school subject at schools, English has not guaranteed efficiency, equity, and access to learning the language.

To mitigate these poor results, the attention has shifted to incorporating the subject earlier in primary school, given its benefits in the acquisition of the language at an early age (Ministerio de Educación, 2012). The number of hours of English has increased, teachers have been trained to teach young learners, and approaches have shifted towards a communicative and holistic approach. In fact, students are now supposed to learn the language and to use it as a tool to communicate in simple situations, to access new knowledge, and to respond to global communication through media and technologies. The lexical dimension is now regarded as an essential component for acquiring fluency, understanding texts, and supporting communication. By the end of 6th grade, students are supposed to manage at least 500 English words (Barahona, 2016).

Even though the new guidelines for language teaching were improved and modernized while emphasizing interesting aspects such as the relevance of vocabulary, there is an imbalance between the development of language skills and children’s cognitive and affective development (Garcia and Mardones, 2012), as the guidelines have not been effectively implemented. Furthermore, the introduction of English is partially effective and needs to be supported by improved resources and enhanced teaching strategies to be fully realized. This expansion must be taken seriously and with a clear understanding of what is happening in EFL teaching regarding young learners (Cameron, 2003).

Young learners and researching with them

Although it is still a controversial topic, from a cognitive perspective, learning a foreign language from an earlier age has proven to be very effective, as the learning curve declines with age in this regard (Hartshorne et al., 2018). Therefore, it is important to consider young learners’ characteristics when implementing initiatives to promote their language learning. Young learners are between 3 and 15 years old, but, within this wide range, students differ from one another in terms of their cognitive, affective, and social characteristics (Nunan, 2011). In these stages, children are still developing their linguistic, cognitive, and social skills (Berk, 2005) and keep learning about their world from their experiences. From a language learning perspective, they extract meaning from context. Learning a foreign language should then expand their experiences and motivation, as well as enhance the use of language in action, as the acquisition of a second language highly depends on the amount of exposure received by children as they benefit from the input (Arikan and Taraf, 2010).

Regarding cognition, their prefrontal cortex is still developing, so their attention span is short. Their working memory is very limited (Alloway et al., 2004), and, as a result, they need to be exposed many times to an experience for them to connect it to pre-existing information (Sweller, 2011). Later, they will become capable of organizing, classifying, and focusing on new information for longer periods of time (Pinter, 2014). Affectively, children are strongly influenced by their social interactions, as they begin to internalize the external assessments of others, which impact their beliefs, learning, and mindsets (Dweck, 2017). They learn within a sociocultural context and build knowledge via social interaction.

Therefore, research should also consider these elements. Children have moved from being objects of analysis to autonomous individuals who can develop their own understanding and views, as well as part-take in social and cultural movements as social actors (Gallacher and Gallagher, 2008). Considering that educational research may have an impact on young learners’ lives by influencing educational policies and practices, it should look for ways to give students more participation in studies (Christensen and Prout, 2002).

Viewer learners, multimodal texts, and memes

Nowadays, young learners live in a visually rich world, where they permanently encounter and create meaning and knowledge through images (Romero and Bobkina, 2017). Visual literacy has become an essential learning skill as they generate multimodal meanings that include written text, visual images, and design elements from a variety of perspectives. Students need to process words and pictures together to find meaning. They must be able to move gracefully and fluently between text and images, between literal and figurative worlds. Therefore, the introduction of words whose meaning may be deduced through images and memes, which combine images and text, is very useful for learners. Students need to find meaning in pictures, which involves a set of skills ranging from identification to contextual or metaphorical interpretation. Therefore, EFL teachers should integrate this aspect of visual literacy while considering that today’s students are constantly consuming images and visual information especially in English. These images have an internal logic and are socially constructed (Shifman, 2014). They can be personalized and customized, so they can adhere to narrower cultures, and they usually prove to be a puzzle related to current events, leading to a humorous pun.

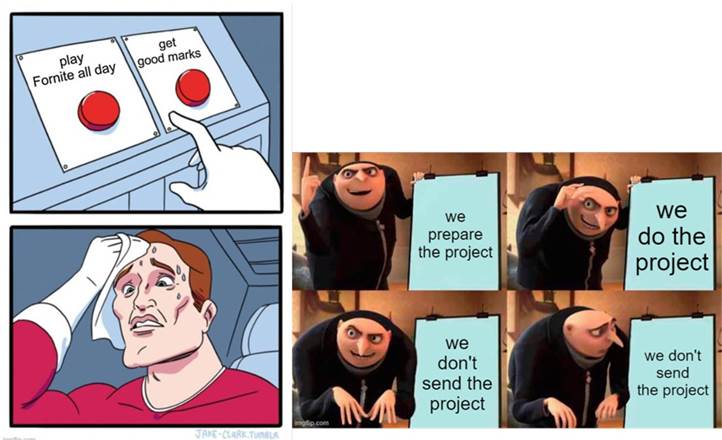

Furthermore, there is a remarkable distance between the texts that students read in school and those they read at home. Monomodal texts still monopolize contemporary language classrooms in many contexts around the world (Serafini, 2014). Consequently, many educators have stated the need to increase the presence of multimodal texts in the language curriculum (Anstey and Bull, 2006). Memes were in this study selected given their ability to create multiple opportunities to develop visual and critical skills in the language classroom, as they are virally transmitted cultural artifacts with socially shared norms and values that can be defined as socially recognized types of communicative action. They evoke a dose of laughter and fascination at the way in which users employ puns and word games with images to design witty and amusing or gloomy messages.

Vocabulary in English language learning

Learning vocabulary plays an important role in language learning, as words play a significant role in expressing our feelings and ideas, as well as in understanding others’ ideas during communication, which cannot take place without enough vocabulary. In language learning, vocabulary is an essential component (Harmon et al., 2009). Therefore, students will always need to expand their knowledge of words in order to develop a reciprocal relation between language use and vocabulary (Nation, 2001).

L2 vocabulary learning progress is often slow and uneven. This is due to a variety of interrelated factors, such as insufficient input, a lack of opportunities to use the language outside the classroom (insufficient output), the teaching methods used (communicative language teaching vs. the grammar-translation method), the amount of time dedicated to the English language in general or to vocabulary learning in particular, and so on. A low amount of regular input in the L2 context means that the opportunities for learning new vocabulary items are limited, with relatively fewer words being acquired incidentally. In this sense, teachers have the greatest influence on the quality and quantity of L2 vocabulary learned by learners (Laufer, 2003). They play a key role and ultimately decide what is learned, so their careful planning and general knowledge of the issues involved in vocabulary learning may help enhance the learning process.

English language learners need to participate in different methodologies to acquire and organize vocabulary into mental schemes. It is not enough with direct instruction. Learners need more opportunities to organize, interconnect, and link previous knowledge to new one in order to process new information. In this way, they can build a ‘stash’ of words to be used both passively and actively. Therefore, teachers have to design a variety of methodologies and activities for students to repeat, retrieve, and put into practice vocabulary words and chunks in meaningful ways, thus ensuring that the information moves into the long-term memory (Thornbury, 2004).

Vocabulary learning requires memory, processing, storing, and using L2 words in productive ways (Nation and Gu, 2007). In the context of EFL, learning vocabulary can be problematic. The English class is one of the sole sources of vocabulary input in schools. Besides, words encoded by learners during lessons can be easily forgotten due to the lack of consolidation through extended practice, language strategies, meaningful input and exposure, and long periods of inactivity known as retention intervals (Loftus and Loftus, 1976). Therefore, vocabulary retention (Richards and Schmidt, 2002) among learners increases very slowly from lesson to lesson, making it more difficult to develop other skills (Neuman and Dwyer, 2009). According to Nation (2015), the acquisition of vocabulary is also related to the number of encounters with words and their intentionality, suggesting that, when deliberate attention is paid by students, the learning process is enhanced.

Nation (2015) also states that combining learning techniques intensively improves vocabulary learning. He emphasizes the importance of the extracurricular time that learners should dedicate to language and vocabulary learning. Repeating vocabulary and seeing the same lexical unit in different contexts allow students to infer the meaning of words and learn about their use, which consolidates the association of new and familiar words (Pigada and Schmitt, 2006). However, educators often ignore these guidelines to avoid having a passive role in the language acquisition process, thus paying minimal attention to vocabulary. Technology is now able to provide young learners with endless resources for language learning if teachers carefully design opportunities for them to become involved in learning experiences. A study conducted by Liu (2016) determined some characteristics that memes should have in second language acquisition (SLA) contexts. She suggests that memes should be as faithful as possible to the original meme in order to ensure an accurate transmission. Moreover, they should be fit for the learning context while considering the four fundamental skills: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. In addition, these SLA memes should be part of a continuous input and output for the students; they need to encounter these memes many times and in as many places as possible. She concludes that memes are a real option in ESL classrooms.

Methodology

Participants

The sample was purposive and classified as discretionary (Palys, 2008). Participants were selected who met certain criteria: age, grade, and weekly hours of English class. The sample comprised 18 young learners who belonged to a 6th grade class from a Chilean school located in Concepción, Chile. They were between 11 and 12 years old. The class was mixed: eight students were male and ten were female. In this school, English classes start from 3rd grade, and students receive three hours of English per week, with lessons emphasizing the communicative and lexical approaches.

Action plan

This project is framed within an action research design (Berg and Lune, 2012) in order for the subjects or participants to experience the intervention process and collect valuable lessons for improving teaching and making changes. Therefore, its design involves the following overlapping stages: planning, action, observation, and reflection (McAteer, 2013).

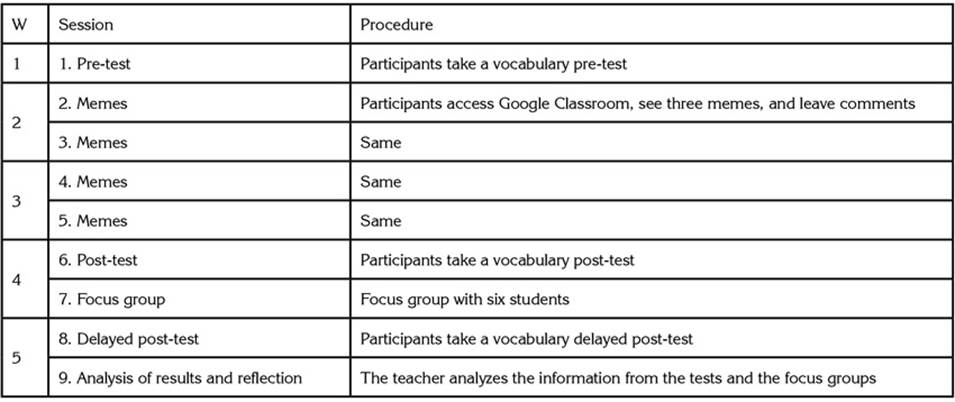

The action plan encompassed a total of nine sessions (Appendix 1) developed in five weeks. The first session involved the application of a vocabulary pre-test. All the participants were assigned the test and had 20 minutes to answer. In the second, third, fourth, and fifth sessions, the teacher posted three memes (Appendix 2) per session in Google Classroom after school hours, usually in the afternoon on Mondays and Thursdays. The students were told to leave comments under the memes. These memes were designed in such a way that they contained the words and vocabulary that they were reviewing within the unit in school. In addition, before starting the action plan, a session was held in which the students were taught how to access the platform and comment on it. They were also given useful and set phrases for them to comment their reactions to the memes. In addition, these memes were selected by considering the latest meme trends on social media, as well as by asking the students themselves beforehand if they knew these images and if they could understand their complexity.

In the sixth session, students took a vocabulary post-test in 20 minutes. In the seventh session, the teacher gathered six students and created focus groups for topics from the script. In the eighth session, the students took a delayed post-test in 20 minutes to check vocabulary retention two weeks after completing the intervention. Finally, in the ninth session, the teacher analyzed the results obtained from all the instruments and reflected on the information gathered for future practices.

Ethical considerations

Before this study was conducted, the parents were informed in detail about the process of the action research in order to avoid any obstacles and obtain their signed permission to publish the results.

Data collection techniques

The data collection techniques used in this research study included the results of pre-, post, and delayed post vocabulary tests as well as a focus group interview.

Tests

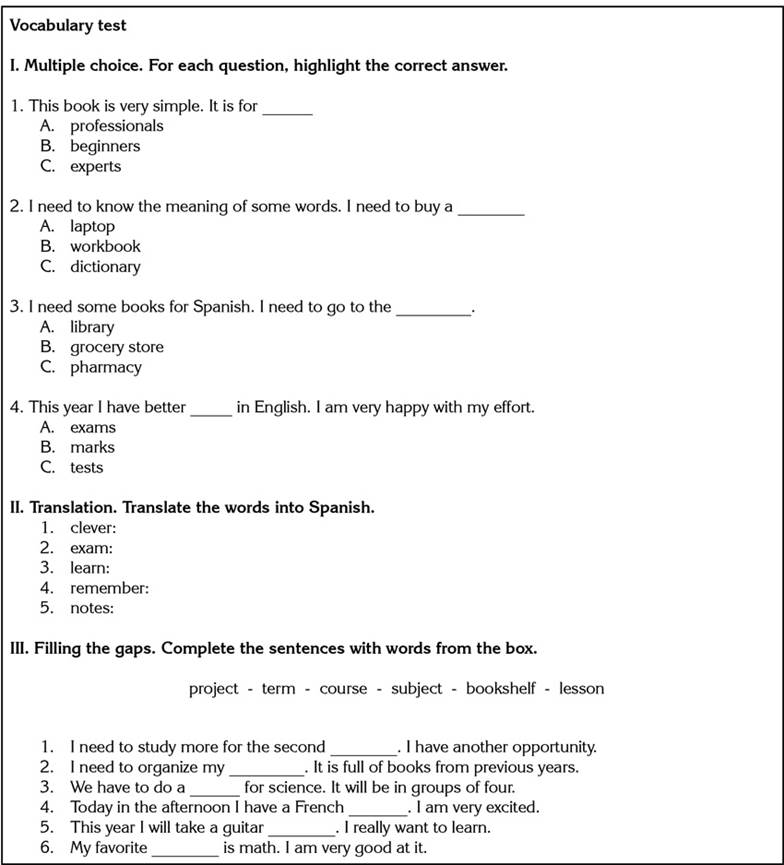

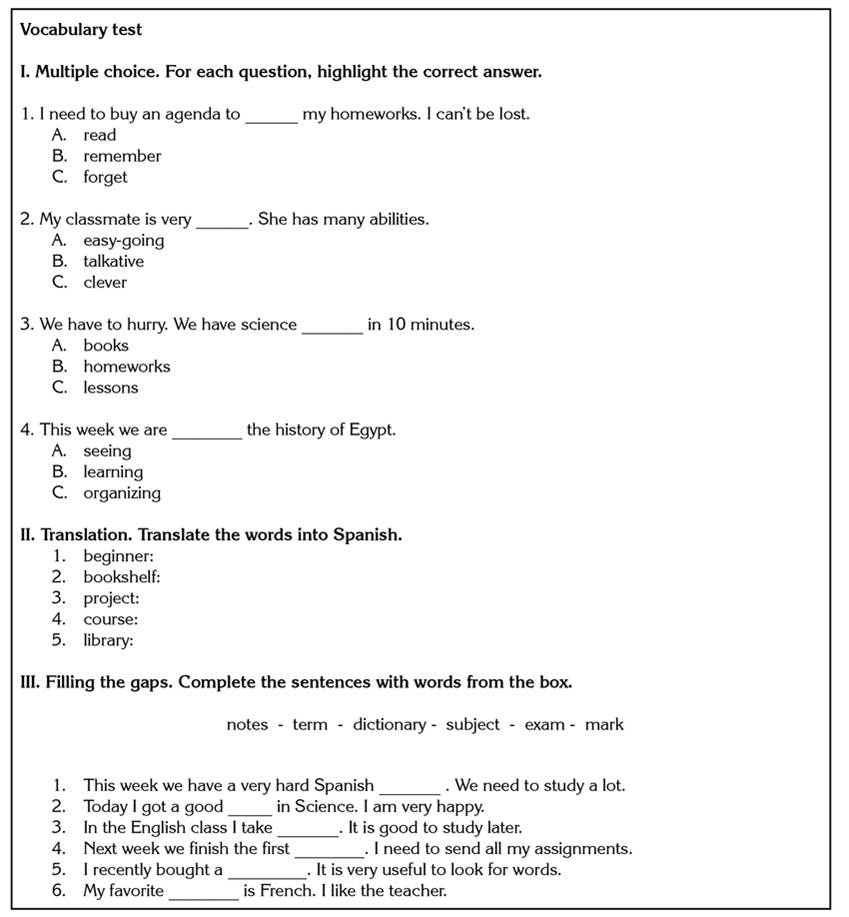

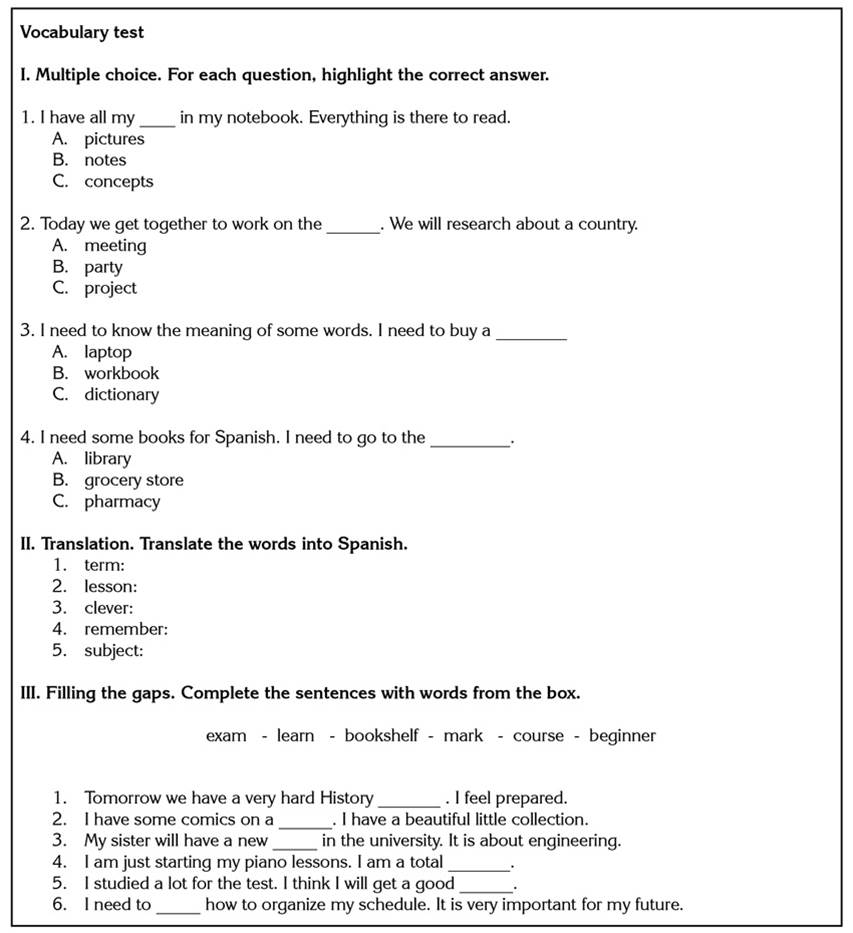

To gather information about the participants’ knowledge, acquisition, and retention of the vocabulary considered for the intervention, three tests were administered. The first one, the pre-test, was administered before the intervention (Appendix 3). The second one, the post-test, was administered right after the intervention (Appendix 4). Finally, the third one was administered two weeks after the intervention (Appendix 5).

In the elaboration of the tests, certain criteria were taken into account. The first criterion was the level of the words, considering that the participants were in 6th grade. To this effect, vocabulary from the A2 level (beginner) of The Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) was chosen, considering that this is the level suggested by the Ministry of Education for 6th graders, as well as the level imparted by the coursebooks used in the school for that grade. The second criterion involved an appropriate list of words. There are some vocabulary lists provided by specialists in the area such as Nation (2006) or Beck et al. (2002). In this intervention, to make sure that the vocabulary was appropriate for the A2 level, words from the Cambridge Assessment English A2 Vocabulary List were chosen. This list was developed by Cambridge English in consultation with experts, and it draws on vocabulary from a corpus of high-frequency words. The list is updated on a regular basis and enables students and teachers to identify the core vocabulary that they should target according to the desired level. The third criterion was the vocabulary from the list. It had to be related to the unit being covered at the moment of the intervention in order to make it appropriate and relevant for the learners and the learning objectives. At this time, the topic being covered was education, and the vocabulary related to this topic involved subjects, school objects, and the dynamics of the teaching and learning process. Therefore, vocabulary from the list that was not covered during the synchronous lessons was assigned to this intervention’s asynchronous time. Thus, 15 words were selected and included in the memes:

beginner (n)

bookshelf (n)

clever (adj)

course (n)

dictionary (n)

exam (n)

learn (v)

lesson (n)

library (n)

mark (n)

notes (n)

project (n)

remember (v)

subject (n)

term (n)

The fourth criterion was the test format. In order to ensure the reliability of the tests, all three were designed with an item format that would allow data to be collected for later analysis, as it was important to determine to what extent the words taught had been mastered by the students, both receptively and productively. Assessing vocabulary poses challenges such as choosing the right format and items (Shen, 2003). Furthermore, it is important for learners to have the opportunity to recognize and produce words (McCarthy et al., 2010). Therefore, for this intervention and the tests, recognition items (multiple choice, true or false, and matching) and productive items (L1 translation, L2 synonyms, gap-fill, and cloze) were employed, as these type of items are widely used and have been validated for vocabulary assessment (Bailey and Curtis, 2015; Brown and Trace, 2017).

Considering these criteria, the three tests were designed using the same vocabulary, albeit in different items for the different assessment instances. To facilitate correction and analysis, each question was assigned 1 point. Each test had a total score of 15 points, one for each word from the list.

Focus group

The focus group consisted of six students representing different levels of achievement during the intervention. This instrument was selected because it creates a safe environment to collect data in participatory research, especially when involving young children (Bagnoli and Clark, 2010). It is also useful to avoid some of the power imbalances between researchers and participants, as they are designed to obtain perceptions on a defined area of interest in a non-threatening environment of disclosure, where people can share ideas, experiences, and attitudes about a topic (Krueger and Casey, 2009). Additionally, they are frequently used in research with children (Pinter and Zandian, 2014).

The participants were required to address a total of six open questions concerning two different dimensions: their general opinion on vocabulary in terms of its importance for learning English and their perceptions on the action plan based on memes to increase their vocabulary(Appendix 5).

The focus group sessions for this research were conducted in Spanish, considering the students’ language competence. The comments provided by the participants in the focus group were transcribed.

Data analysis techniques

Two techniques were used to analyze the data: descriptive statistics for the tests and thematic analysis for the focus group.

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics such as frequencies and percentages were used to summarize findings from the pre-, post-, and delayed post-test (Dörnyei, 2007). This technique was used to compare the performance of the participants in three moments: before the intervention, immediately after the intervention, and two weeks after the end of the intervention. All the information collected was tabulated, and figures were used to describe and interpret the data.

Thematic analysis

Thematic analysis was used to analyze the data collected from the focus group. This technique is useful to identify, analyze, and report patterns within data (Braun and Clarke, 2006), and it must be rigorously and methodically implemented in order to obtain meaningful and useful results (Nowell et al., 2017).

The focus group sessions were transcribed and analyzed. The analytical stages considered were familiarizing with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing, and defining and naming the themes. Thus, the comments made by the participating students were categorized into three main dimensions: the importance of vocabulary and ways to acquire new vocabulary, memes, and images for learning vocabulary.

Results

This section presents the results obtained from the vocabulary tests and the focus group interviews applied after the intervention.

Pre-test

The pre-test consisted of vocabulary items intended to assess and gather information about the participants’ vocabulary knowledge before the intervention. The maximum score was 15 points.

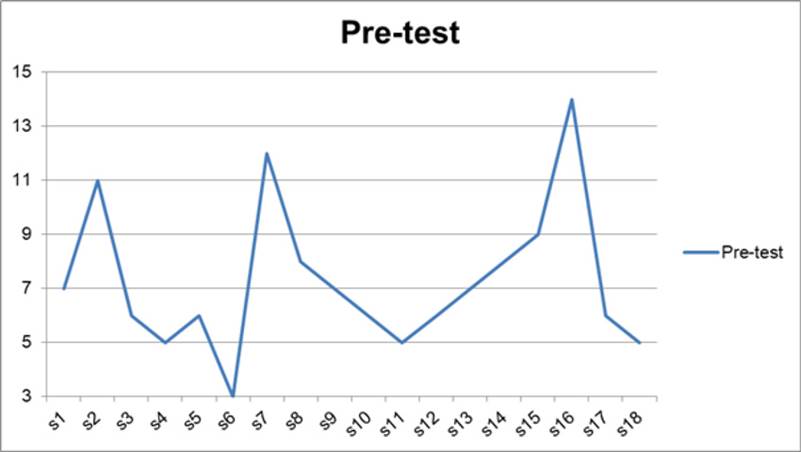

Figure 1 provides an overview of the participants’ performances in the vocabulary pre-test. The mean for this test was 7.3 out of 15. It is interesting to note that, at this point, the group seems to be heterogeneous, as there are different levels of proficiency. It can also be seen that S16 is an outlier.

Post-test

The post-test consisted of vocabulary items similar to the pre-test. This test was administered immediately after the intervention. The maximum score was 15 points.

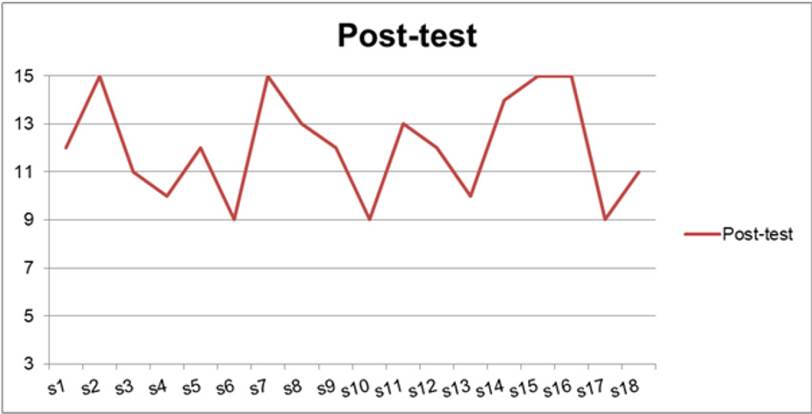

Figure 2 provides an overview of the young learners’ performances in the vocabulary post-test conducted immediately after the intervention with memes. The mean for this post-test was 12.1. There was an increase of 4.8 points in comparison with the pre-test. It is also worth noting that four students reached the maximum score, as well as the fact that most of the students increased their scores and that a steady progression from the previous test could be observed.

Delayed post-test

The delayed post-test consisted of vocabulary items similar to the pre-test and post-test. This test was administered two weeks after the intervention and intended to gather information about vocabulary acquisition and retention. The maximum score was 15 points.

Figure 3 provides an overview of the students’ performances in the vocabulary delayed post-test. The mean for this delayed post-test was 11.2. There was a slight decrease from the post-test, but the scores were still higher than those of the pre-test. These results show that, even though two weeks passed after the end of the intervention, the students still remembered the vocabulary acquired during the action research, which could be attributed to the methodology in which students linked vocabulary to real and fun instances.

Focus group

The focus group interview was conducted after the intervention had been completed, and the subsequent analysis of the results was based on relevant thematic information obtained from transcripts of the students’ comments, which were grouped into three main dimensions: the importance of vocabulary, ways to acquire new vocabulary, and memes and images for learning vocabulary.

Dimension 1: The importance of vocabulary

The first dimension that emerged is the importance that students place on knowing English vocabulary. The participants stated that knowing words and how to use them allows them to speak and understand English. They said that sometimes, when they want to say something, they are missing a word, which is why they cannot complete what they want to say. This is a common problem in beginner students. In general, they can understand grammatical rules similar to those of their mother tongue, but, when it comes to speaking or writing (production-oriented activities), there are gaps that they do not know how to fill. This affects them and makes them believe that what they do not know is much more than what they do.

R: How important is knowing words in English?

S2: Very important because, in that way, you can convey messages.

S4: Important because sometimes I want to say something but I lack some words, so I can’t say what I want to say.

S6: It is also important to understand English.

Dimension 2: Ways to acquire new vocabulary

The second dimension has to do with the ways in which young students learn English words. In general, they have a variety of ways to learn vocabulary. However, few of them are related to the school environment, but rather to what they do outside school in their free time. The participants stated that, thanks to music, videos, videogames, and Internet slang, they can learn new words to enhance their mental schemes and be able to associate new words. This is an important point considering the few English hours per week in comparison with other subjects such as math or science. The belief that only school classes can lead to effective language learning can be a dangerous illusion, leading students to believe that, if they are not capable of learning in school, they are not capable of learning anywhere.

R: How do you acquire new words in English?

S1: I learn words when I listen to music.

S5: I learn words when playing video games online. Sometimes the videogames are in English, or you have to write in English to other people.

S3: I also learn new vocabulary on Instagram because I follow some English-speaking people.

S4: Yes. That’s useful because, after that, sometimes I see the words in school.

Dimension 3: Memes and images in learning vocabulary

The third dimension has to do with the intervention itself. Consulting the opinions of young learners can shed light on their emotional connection to classroom activities and how they feel when adult teachers energize activities with tools that are more familiar and generational to them. The participants found the intervention very fun and novel for a variety of reasons. Among them, they found it interesting that memes were used as a pedagogical activity. It also made them realize that they can learn words in a fun and funny way. Finally, learning vocabulary with this methodology made them feel that they could relate the words with others and better retain them for later use.

R: What do you think of the activity with memes?

S2: It was funny! When I was able to understand the meme, it was funny.

S4: I didn’t know that memes could be useful to learn words.

S5: It was interesting and funny because we see memes on the internet.

S6: It was good because now I see some words that I saw in the memes and I remember them.

Analysis and discussion of results

As discovered throughout the different stages of this research, learners maintained the maximum score (15 points) and showed a significant improvement in vocabulary acquisition compared to the initial stage (4.8 points higher in the post-test and 3.9 in the delayed post-test). This is a good indication that the action plan with memes can be effective for vocabulary acquisition. A slight decrease is observed when comparing the post- and delayed post-tests (0.9 points). However, given the time frame in which the latter was administered (two weeks after the intervention), it is evident that students remember the vocabulary acquired during the instruction period. In this sense, the role of images is crucial, as some cognitive theories such as dual-coding processing have shown (Paivio, 2006).

The focus group reported a high validation of the use of vocabulary and its relevance for communicating. Learners describe vocabulary as a tool to understand and produce language; they value the acquisition of new words, as they allow them to part-take in conversations and convey meaning. The lack of vocabulary and the ability to paraphrase or find synonyms indirectly refrains students from using the language.

Concerning the ways to acquire a new language, young learners engage with the L2 through songs, videos, and videogames in their free time. The focus group answers show how students not only receive input from different sources, but also use it to engage in conversations. Furthermore, they are capable of connecting their background knowledge with the vocabulary studied in class.

As for memes in learning vocabulary, the perception of students on the use of this strategy is positive. They described it as a novel and fun way of learning in the classroom. Students did not see the use of multimodal texts as frequent classroom practice, but they appreciated it. During the focus group sessions, the learners described the experience as interesting and found it useful, as the memes were similar to what they are used to seeing on the Internet. This is consistent with what was proposed by Wigfield and Eccles (2000): motivation increases when the learning focus has a connection and/or is reinforced by learners’ interests.

The results illustrate a decisive validation by students on the use of novel and engaging language learning strategies. This could have a direct correlation with the results obtained, as students felt drawn to learn and practice with what they consider to be a real-life situation. As discovered in the focus group sessions, students encounter multimodal texts when using the Internet in their free time, which makes direct learning even more meaningful. Moreover, this could be connected to a lowering of their affective filter, which makes them feel more comfortable and at ease when using the language.

The increase in vocabulary acquisition and retention could be explained by the different levels of understanding involved in deciphering a multimodal text, as processing it includes the comprehension of words and their context. Vocabulary retention can be improved when using the knowledge of words in different contexts and meanings, that is, in comparison with definition or identification alone. Furthermore, there is a much deeper cognitive process involved when looking at memes, as the use of vocabulary has the essential function of creating an understanding of a meaningful phrase. This process becomes substantial for young learners, given that their working memory is limited, and they need to encounter new words in many retrieval opportunities in order to finally acquire vocabulary (Karpicke, 2012; Sweller, 2011).

Our findings support the notion that multimodal texts (memes) have a positive outcome when used in the classroom, especially for vocabulary retention, as they connect with learners’ interests and backgrounds. Memes are positively perceived by learners as an innovative strategy in the classroom and improve intrinsic motivation. They are a means of communication whose understanding involves cultural context and background knowledge, and they are present in different forms in most of the current social media platforms. This could explain the results obtained in the post-tests, as vocabulary was indirectly and unconsciously reinforced by learners during the intervention. This is supported by Arikan and Taraf (2010) , who argue that exposure benefits the acquisition of new content.

Further studies should focus on researching the effect and acquisition of new words through the use of multimodal texts after extended periods of no exposure to them outside the classroom or while using the Internet.

Conclusion

There is no agreement on the perfect method or strategy for teaching language in the classroom. However, the direction followed by most teachers is to innovate through the use of technologies and experiences that connect with their students’ interests. Multimodal texts (memes) have been found to support and enhance the acquisition of new vocabulary in young learners. From their perspective, these learning and instruction methods represent a novelty and make the learning process more engaging, as they directly relate to their interests, contexts, and -most of the time- sense of humor. Therefore, educators should not avoid the use of memes, especially taking into account that they provide comprehensible input to students (Krashen, 1993) while at the same time lowering their stress level and affective filter, thus aiding comprehension.

This study described the beneficial effects of including multimodal texts in the classroom. Not only did students perform well in the different evaluation instances, but they also approved the use of this strategy by teachers, describing it as a novel and fun way of learning and connecting with their background knowledge and spare time activities. The results also show how the use of memes increases the second dimension of language learning, as the new ways in which students acquire knowledge/vocabulary often have no connection to what they do in school. Pre-, post-, and delayed post-tests provided an overview of the students’ performance and how it increases after implementing the multimodal text strategy.

It is fundamental to keep up with students interests’ and background knowledge in order to innovate in the classroom. Furthermore, when regarding students as social actors and involving them in the research and planning of the learning process, their insights can provide deeper knowledge about the use of methodologies and strategies, as well as of their effectiveness in the classroom.