Introduction

Contextualizing the materials used in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teaching is essential for achieving meaningful learning, as the content of the materials is in close relationship with learners’ needs. In order to teach EFL to a specific population with unique contextual requirements, it is imperative to utilize materials supported by “an informed methodology that validates the efficiency, appropriateness, and relevance of materials within the context of learning a language” (Núñez et al., 2012, p. 10). This research study aims to improve the language proficiency of students in a Colombian educational context by implementing teacher-made materials designed to foster their writing skills.

During my time as an English teacher at the school where this study was conducted, I observed a consistent pattern of gaps in students’ writing compositions, including grammatical and vocabulary errors, as well as unclear and ambiguous ideas. Despite receiving regular feedback, those errors remained frequent. It appeared that 10th-grade students faced challenges in writing and clearly structuring their ideas in their compositions. To tackle this problem, an entry survey was conducted to assess the students’ needs and kept detailed notes of classroom observations in a reflective journal.

The information above allowed me to identify two key aspects for conducting this study. First, learners would prefer to learn English using materials that are familiar to them. Second, they also prefer those that are tailored to their own context. Howard and Major (2004) claim that non-specific commercial materials used for EFL teaching do not meet the specific needs of diverse cultural and educational settings. Therefore, it is necessary to develop materials that not only focus on students’ needs, but also facilitate the development of specific language skills, such as writing. This suggests that learners can connect what they understand to what they can produce in written form using EFL in contextualized teacher-made materials.

Theoretical Framework

This section is concerned with conceptualizing the main constructs that underpin this study; namely, teacher-made materials from the perspective of Materials Development (MD) as a field of study and meaningful learning as the key element in the development of materials that focus on implementing activities to widely foster the EFL writing skill.

Materials Development

According to Núñez and Téllez (2015), Materials Development (MD) focuses on the procedures to analyze the contributions of using materials for EFL teaching and learning. As a result, it favors language teaching and learning in a positive way. Furthermore, MD has transformed its nature from a practical perspective to an academic field of study (Tomlinson, 2012). In this regard, MD encompasses all the procedures that EFL teachers can employ to foster language learning and use through the implementation of supplementary resources in the classroom.

Likewise, Núñez et al. (2013) maintain that MD “demands an informed methodology that validates the efficiency, appropriateness, and relevance of materials within the context of learning a language” (p. 10) and generates effective learning environments (Núñez & Téllez, 2009). MD plays a fundamental role in EFL teaching and learning since it provides solid insights on what should be done, and especially, on how it should be done to create materials that address genuine needs, interests, and expectations of learners. Ideally, materials should be theoretically informed, implemented, evaluated, and adjusted to validate their suitability, pertinence, and effectiveness in language learning and teaching contexts.

Materials. Materials can currently be seen in many ways, and according to Tomlinson (1998) , “Materials are anything which is done by writers, teachers, or learners to provide sources of language input and to exploit those sources in ways which maximize the likelihood of intake” (p. 2). Tomlinson also contends that materials entail all of the teaching resources used to present the language (2003, p. 2). In light of this, the language teaching resources used by EFL teachers remain a valuable tool that guides and facilitates students’ achievement of language learning goals.

The use of materials also brings together cultural knowledge, understanding, and learning. Accordingly, Rico (2012) defines them as essential resources for the development of competencies and cultural elements from the target language. Consequently, materials should foster respect for difference and diversity to avoid limiting the spread of cultural knowledge and understanding worldwide; they should also take advantage of the flow of content or knowledge of the given discipline they promote to augment and enrich transdisciplinary inquiry and research.

Teacher-made materials. Teacher-made materials can be created or adapted in the quest of helping students’ EFL learning. However, Tomlinson (2003) points out some issues about inauthentic or contrived materials as these can dissuade learners from genuine language practice. Instead, created materials are more suitable since they are contextualized to the reality of the language learners. In this respect, Núñez (2010) asserts that materials based on the situational characteristics that support their design facilitate the achievement of learning goals.

These kinds of materials connect what is taught in the classroom to learners’ contextual realities, personal and academic preferences, and interest in the world around them. Similarly, teacher-made materials can be much more motivating for students since they find it useful to learn EFL using topics that are familiar to them. In sum, teacher-made materials are specially designed to fulfill specific instructional objectives that are generally stated considering students’ language learning, academic, and affective needs.

Meaningful Learning

Meaningful learning may be seen as a pillar to build up knowledge, as it relies on the construction of knowledge and language development based on the relationship established between the learners’ previous knowledge and their cognitive structures. Ausubel & Fitzgerald (1961) sustained that cognitive structures refer to “an individual’s organization, stability, and clarity of knowledge in a particular subject-matter field relative to meaningful new learning tasks in this field” (p. 500).

As meaningful learning occurs when new information is connected to the learner’s pre-existing cognitive structures, the pedagogical intervention envisioned for this study considers the presentation of both new information and the organization of learning activities in an appealing and engaging way. Subsequently, the learners relate such information to what they already know, maximizing the possibility of improving their EFL learning. Therefore, the theory of meaningful learning suits the materials that were designed and implemented for this research study as it integrates learners’ backgrounds and individual experiences. These, at the same time, lead to activities that engage students in producing language through the activities proposed in the teacher-made materials.

Reception is also an important issue in meaningful learning. This is mainly because meaningful learning focuses more on intake and its connection to learners’ preconceptions. It is important to clarify that the nature of meaningful learning is not related to rote learning and memorization principles (Ausubel & Fitzgerald, 1961). This distinction is important because the former implies the incorporation of new knowledge into cognitive structures, while the latter only involves recalling stored and memorized information without any meaningful application.

Accordingly, meaningful learning acknowledges students’ own culture and background to support the process of MD in EFL learning. Likewise, meaningful learning is a recurrent and salient concept in the field of MD that aims to substantially impact EFL learning. As Tomlinson (2003) affirms, “impact is achieved when materials have a noticeable effect on learners, that is, when the learner’s curiosity, interest, and attention are attracted” (p. 8). Hence, the impact is provided by the connection of students’ previous knowledge, their new mental representations, and how they link this knowledge to language use when writing. This, in turn, enable students to successfully complete learning activities proposed in the teacher-made materials.

Writing

Writing is a complex and demanding language skill as it challenges a language user to carefully produce language. Equally, writing focuses on providing accuracy when brainstorming, organizing, and polishing ideas into a cohesive text for effective communication (Ochoa Alpala & Medina Peña, 2014). As contended by Quintero (2008) , writing enables individuals to organize information and communicate properly. Hence, it is a difficult task for many because it requires putting thoughts together coherently. Mastering writing takes time. It is a gradual process that must be undertaken in the EFL classroom.

Therefore, working on the language features to achieve comprehensible writing is not a simple ability to be fostered, but rather a skill that must be gradually developed through cognitive procedures and meaningful and sequenced materials and writing strategies. This understanding of writing already indicates its developmental importance. There are two main approaches to consider when teaching writing: writing as a process and writing as a product.

First, writing as a process focuses on the stages that are followed to achieve a well-written text. These stages are the result of cognitive and mental processes carried out by the writer. According to Langan (2001) , the writing-as-a-process approach does not just center upon the product but it pays special attention to the procedures, steps, and stages students follow to complete a writing activity. This approach implies taking into consideration the beliefs and habits of the writer because those features affect the process itself.

Second, writing as a product centers on what the writers need to improve by themselves. They identify the key features and relevant facts of a given task and complete it by referring to samples. Writing as a product is a classical approach that enables learners to complete specific written tasks that are usually modeled by the teacher (Gabrielatos, 2002). In other words, it merely focuses on repeating what has been already done, exclusively considering what might be produced on a sheet of paper to compare the edition and the process made by the writer. This approach is oriented towards effectively organizing information and ideas based on their relevance in order to emphasize the intended result of the assigned task.

Pedagogical Design

The teacher-made materials used in this study were designed following the MD framework proposed by Núñez and Tellez (2009). They consisted of a five-lesson workshop based on meaningful learning to foster writing skills, which incorporated the process approach to writing (pre-writing, while writing, and post-writing) into the writing lesson. The meaningful learning approach for language was employed to foster writing skills in tenth-grade students, with the process guided by useful writing tips and opportunities for peer and teacher-feedback in the EFL classroom. Students were expected to write texts expressing their perceptions, opinions, and feelings on topics of their personal interest to share with their peers and the teacher during the socialization of the lessons. Accordingly, the pedagogical intervention contemplated Tomlinson’s (1998) Second Language Acquisition (SLA) principles, with seven being prioritized.

First, materials achieve impact through novelty, variety, attractive presentation, and appealing content. Second, materials are perceived as relevant and useful by the learner. Third, materials offer plenty of free practice. Fourth, materials provide opportunities for communicative purposes in L2, thereby fostering language use, not just usage. Fifth, materials help learners feel at ease. Sixth, materials facilitate students’ self-investment, which aids the learner in making efficient use of the resources to facilitate self-discovery. Last, materials provide opportunities for outcome feedback. Consequently, these SLA principles were considered to guarantee suitability, pertinence, and effectiveness of the proposed teacher-made materials.

Research Question and Objectives

The aim of this research study is to answer the following question: How do teacher-made materials, based on meaningful learning, develop tenth-grade students’ writing skills at a state-funded school in Colombia? To address this question, the following objectives were established:

To explore the contributions of teacher-made materials based on meaningful learning to the development of tenth-grade students’ writing skills.

To appraise the suitability and usefulness of teacher-made materials in the development of students’ writing skills.

To describe the role of the meaningful learning approach in fostering students’ writing skills.

To identify and describe the writing skills that students used while interacting with teacher-made materials.

Research Design

Method

For this study, I have chosen to use the qualitative research approach because its characteristics helped me to gain a deeper understanding of how teacher-made material based on meaningful learning contribute to the development of writing skills in tenth graders. As Sandin (2003) notes, qualitative research allows for a comprehension of a specific phenomenon and its interaction with a determined educational social context. Hence, this study aims to explore and draw conclusions about the implications of utilizing teacher-made material based on meaningful learning to foster writing skills.

Given the nature of my research study, action research is well-suited for the development and implementation of my pedagogical intervention. Indeed, action research allows the researcher to obtain real information about language learning events that take place within a particular social context (Creswell, 2015). In this sense, it provides realistic data that, according to Burns (2010) , cannot be generalized and permits the exploration of pedagogical procedures in specific educational settings to inform decision-making and improvement. In other words, since each class can be considered a different unique setting, this type of research study seeks to generate knowledge and propose and implement a pedagogical innovation that promotes change in both the teacher’s pedagogical practice and the students’ learning and performance.

In order to implement the pedagogical intervention and analyze the results, it was necessary to establish the action research cycle. In this regard, Kemmis et al. (as cited in Burns, 2015) focus on four action research stages, which include planning the pedagogical intervention, acting when implementing the intervention to solve or alleviate the identified problem, observing and describing the behavior and response of the participants, and reflecting on the data collected (See Figure 1). These stages allow for an exploration of the possible contributions of the pedagogical intervention.

Participants

The participants in this study were 35 tenth graders from a state-funded school in Florencia-Caquetá, Colombia. The group consisted of 12 boys and 23 girls with an average age between fourteen and sixteen years old and most of them belonged to the first and second levels of social strata. The participants signed a consent form and were selected based upon their availability to participate in the pedagogical intervention. Accessibility was ensured due to my consistent communication with the group in my capacity as their English teacher. The convenience sampling technique facilitates the selection of participants based on their availability and accessibility to the researcher (Patton, 2014; Stevens, 2012). This technique was suitable for this study because the students showed willingness to participate, and their performance during prior writing activities and the needs analysis indicated they were an ideal group for whom to implement the intervention.

Data Collection Instruments

Data collection instruments play a crucial role in providing the researcher with sets of information to be systematized, codified, reduced, and interpreted to generate preliminary salient issues that give rise to research categories and subcategories. For this research study, I have chosen to use the following instruments as sources of data to be systematized, analyzed, and justified in accordance with the established research objectives: students’ artifacts, teacher’s field notes, and a focus-group interview.

Regarding artifacts, Arhar et al. (2001) state that students’ products and reports provide expressive information that can enable the researcher to obtain unique data different from those collected from other sources of information. Correspondingly, artifacts provide valuable information regarding 10th graders’ interactions with teacher-made materials. Such artifacts serve as a source of tangible information to perceive students’ interactions with the teacher-made materials and their language use.

Alternatively, the teacher’s field notes record specific information about what it is observed during a pedagogical intervention (Lankshear & Knobel, 2004). Moreover, they allow especial attention to be given to the progress and performance of students while completing the written assignments in the workshop. While registering information in the field notes, I could record specific behaviors, feelings, opinions, and perceptions tenth graders had while interacting with the teacher-made materials.

Finally, in relation to the focus-group interview, Bryman (2012) perceives it as an opportunity to record in-depth perceptions from a group of participants in a research study on a given issue. All in all, the purpose of the focus-group interview was to ask questions focused on participants’ insights into the teacher-made materials used to enhance their writing skills in a meaningful way.

Data Analysis

To analyze the data collected, I used the grounded theory approach highlighted by Corbin and Strauss (2014) . This approach allows for the exploration of new information, general ideas, and the advancement of any necessary clarifications while offering new insights into an assortment of new experiences. The data collected through the pedagogical intervention served as a basis for determining and displaying the contribution of the teacher-made materials, the role of meaningful learning, and the enhancement of the EFL writing skill.

The process of data analysis began with a review of the students’ artifacts, including their self-assessments. Then, it was necessary to transcribe the teacher’s field notes and the focus group interview conducted at the end of the pedagogical intervention. In order to identify the most relevant information in the data set, I used the color-coding technique, as described by Stottok et al. (2011) , which highlighted the most recurrent patterns in the data. Burns (1999) defines ‘coding’ as a procedure to organize and systematize data in a more ordered way by establishing categories. Bergaus (2015) , in turn, highlights color coding as a process which enables researchers to sort through categories and codes quickly, thus facilitating easy access to required information.

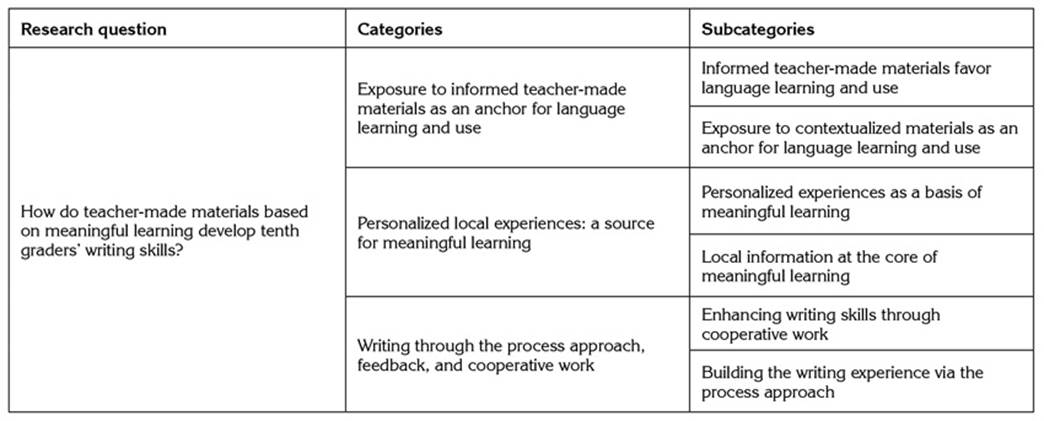

Afterwards, I proceeded to reduce the data by identifying commonalities and establishing relationships between the most salient and recurrent patterns. Next, I triangulated the data to avoid bias. Flick (2009) asserts that triangulation of data takes into account multiple insights on a given issue in the research exercise. Therefore, students’ perceptions considered when triangulating the information in the data analysis were connected to the use of the information resulting from the instruments and the theoretical foundations used to support the research categories as shown in Table 1.

Findings and Discussions

In this section, findings are displayed according to the research categories and subcategories that were previously established.

Exposure to informed teacher-made materials as an anchor for language learning and use

The importance of this category lies in the assumption that teacher-made materials should follow an informed framework that makes them engaging and appealing to learners. By doing so, learners were able to actively participate in the learning process while using the language through the various activities outlined in the teacher-made materials. This assumption is supported by Núñez et al. (2004) , who stated that materials need to be developed following an informed MD framework. Therefore, it is crucial for teachers to have a good understanding of MD frameworks when developing materials, as this enables them to make informed decisions when proposing materials with their own contextualized frameworks for pedagogical interventions. Thus, exposing learners to teacher-made materials helps them to use the language they are learning in everyday situations and to understand its functionality as they work on activities tailored to their own interests.

Informed Teacher-Made Materials Favor Language Learning and Use. This subcategory supports the fact that teacher-made materials informed by contextualized SLA principles offer greater possibilities for students to receive the materials positively and greater levels of EFL learning. Regarding the reception of materials, Núñez and Téllez (2009) claim that “the degree of acceptance by learners that teaching materials have may vary greatly according to the novelty, variety, presentation, and content used in them” (p. 186). As for language learning, Núñez (2010) ascertains that teacher-developed materials are more likely to address students’ needs as well as the situational and learning demands of the context, since they offer the “possibility of prioritizing the learners and placing them at the center of the language program while acquainting them with the current world” (Núñez et al., 2004, p. 129).

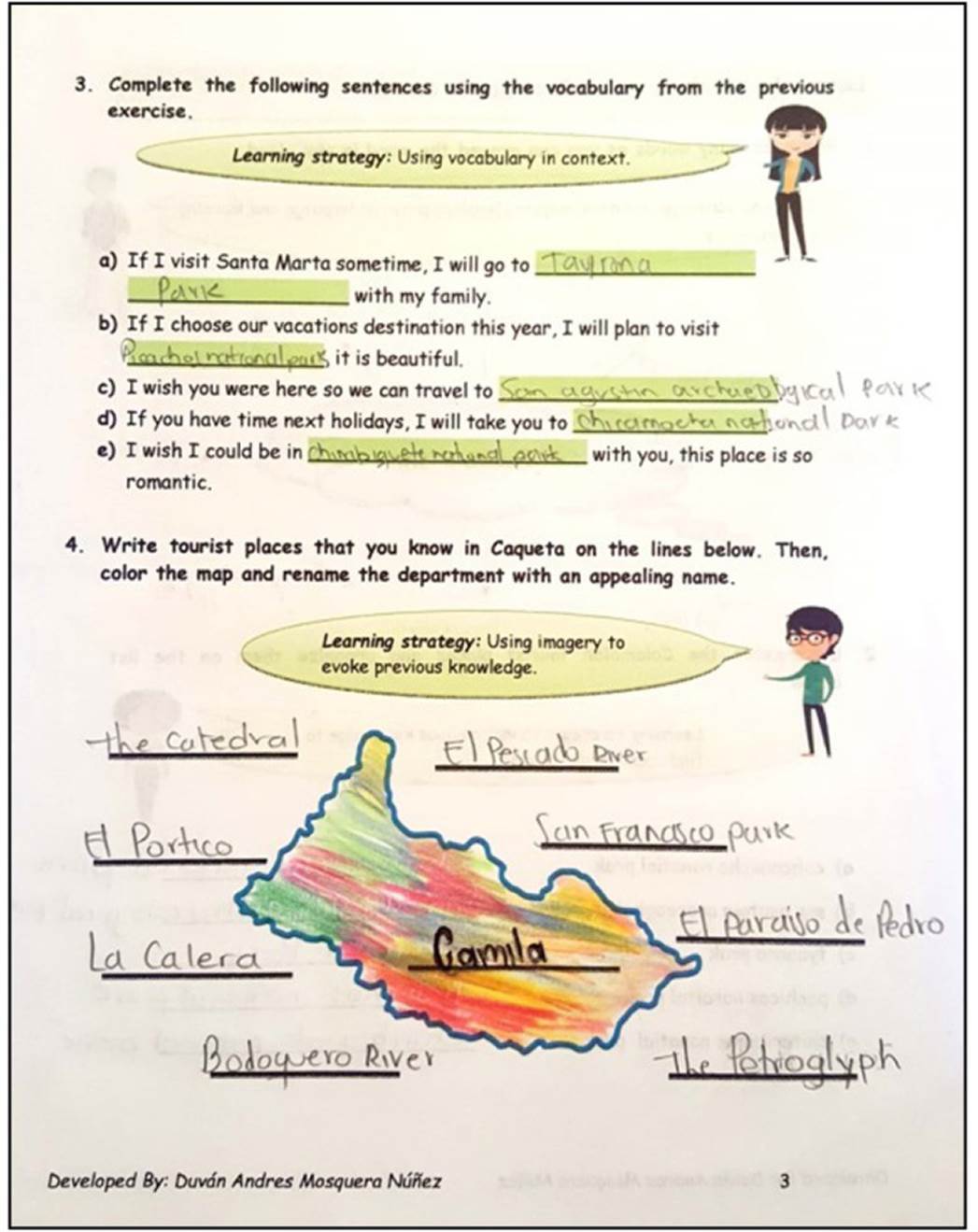

Accordingly, the inclusion of several communicative activities in the workshop allowed leaners to draw on their previous language knowledge and cultural background, and apply it to the activities at hand. As a result, leaners were engaged in the completion of the proposed learning activities (See Figure 2), especially those that focused on contextualized grammar and vocabulary usage. Additionally, the workshop provided a variety of activities aimed at exposing the students to more opportunities for self-investment in contextualized language learning and use. Exposing students to a variety of activities in the workshop encouraged them to use the language in different contexts. The more attractive and contextualized the teacher-made materials are, the more positive results in terms of language learning and use.

Exposure to Contextualized Materials as an Anchor for Language Learning and Use.

This subcategory emphasizes the importance of contextualizing teacher-made materials when developing a pedagogical intervention in order to provide an effective foundation for students’ language learning and use. This assumption plays a vital role in the field of MD due to the lack of contextualization in standardized materials offered by publishing houses. Howard and Major (2004) assert that generic teaching materials do not effectively meet the specific learning needs of students from different contexts and cultural backgrounds. Therefore, these types of materials may sometimes be seen as a useless tool for language teaching (Gilmore, 2007; Núñez & Tellez, 2009, Núñez 2010).

According to Núñez (2010) , “learning materials should keep a balance among students’ language learning and affective needs, interests, expectations, and the institutional policies” (pp. 36-37). Unlike standardized and routinized materials (Littlejohn, 2012), contextualized materials respond and cater to the students’ needs and interests, creating greater opportunities for better language learning and use. Additionally, contextualizing teacher-made materials aims at getting students involved in language learning and use. When students realize how much they can learn by relating their learning to their own context and realities, language learning and use occur. As per Lopera (2014), materials that are designed by teachers have the unique quality of being developed with specific language achievements in mind, something lacking in commercial materials. All in all, language learning and use is developed under the conception of materials that privilege real-life issues and contextualized learning activities.

Personalized Local Experiences: A Source for Meaningful Learning

This category describes the role of the meaningful learning approach in enhancing students’ writing skills. The three-fold principle of fostering meaningful learning includes incorporating general ideas of a subject, using contextualized instructional materials, and linking the students’ learning experiences with the materials and their background knowledge. The use of local knowledge and previous experiences in every lesson of the workshop played a central role in helping the students learn meaningfully. According to Ausubel and Fitzgerald (1961) , accumulating previous knowledge and experiences serves as a basis for new knowledge to take place. Besides being exposed to new learning experiences based on their previous knowledge, the students used language imprecisely within a context that provided them with meaningful resources to complete the activities proposed in the materials, enabling the 10th graders to use the language for communitive purposes.

Personalized Experiences as a Basis of Meaningful Learning. To support this subcategory, the personalized experiences proposed in the teacher-made workshop constitutes the basis of meaningful learning. As stated by Rico (2010), “experiential activities and intake response activities” are used to explore senses that can be connected to meaningful learning. Moreover, these activities, continues the author, “trigger connections in the mind of the learner between their prior experience and what they will encounter in the text” (p. 96). Implementing experiential activities which are related to the learners’ contexts and backgrounds facilitated the completion of the activities in the teacher-made workshop and the achievement of meaningful learning, as argued in the following sections.

The personalized learning activities provided a number of sources for meaningful learning. This is also perceived by the learners in the content and type of activities. The inclusion of content and activities allowed them to identify several elements from their own culture and personal experiences that fostered and accelerated their learning in an enjoyable and meaningful way. This happened because, as mentioned before, the activities were carefully designed and sequenced first, to attend to learners’ needs, interests, and expectations, and second, to gradually guide them into a new and meaningful learning experience. This can be evidenced in the following excerpt of the field notes.

Once again, the use of familiar information and contextualization of the information helped students to get better results when completing the proposed activities. In doing so, students show a good command of the language and meaningful learning can be evinced when they declare how much the materials and activities contributed to their language learning. Student 18 says “con este vocabulario sí aprendo mejor porque conozco estos lugares y todo” (with this vocabulary I learn better because I know these places and everything) Student 24 says “así es más fácil aprender porque usamos cosas que conocemos” (this way is easier to learn because we use things that we know) (sic). These comments allow me to notice that the language is being learnt in a meaningful way. (sic). (Field notes, workshop 1, lesson 3)

Local Information at the Core of Meaningful Learning. This category evinces the role of local information in the teacher-made workshop for fostering meaningful learning in language learners. Since language and culture are closely connected, learners start comprehending their localized cultural knowledge using the language meaningfully. Acknowledging the socio-cultural theory of Vygotsky (1995) , a number of scholars have addressed the significant role of culture in the study of a language (Goldstein, 2015; Gómez, 2015; Pulverness & Tomlinson, 2003; Rico, 2012; among others). Therefore, the references to local information made in the workshop were intentional, aimed at engaging 10th graders in completing the activities in the workshop and fostering meaningful EFL learning. Moreover, this local information serves as the necessary input for learners to achieve meaningful learning. Tomlinson (2010) asserts that learners need to be aware of the importance of using this input so learning can positively take place. Then, localized cultural information, as a valuable and comprehensible input, is at the core of meaningful learning.

Writing through the Process Approach, Feedback, and Cooperative Work

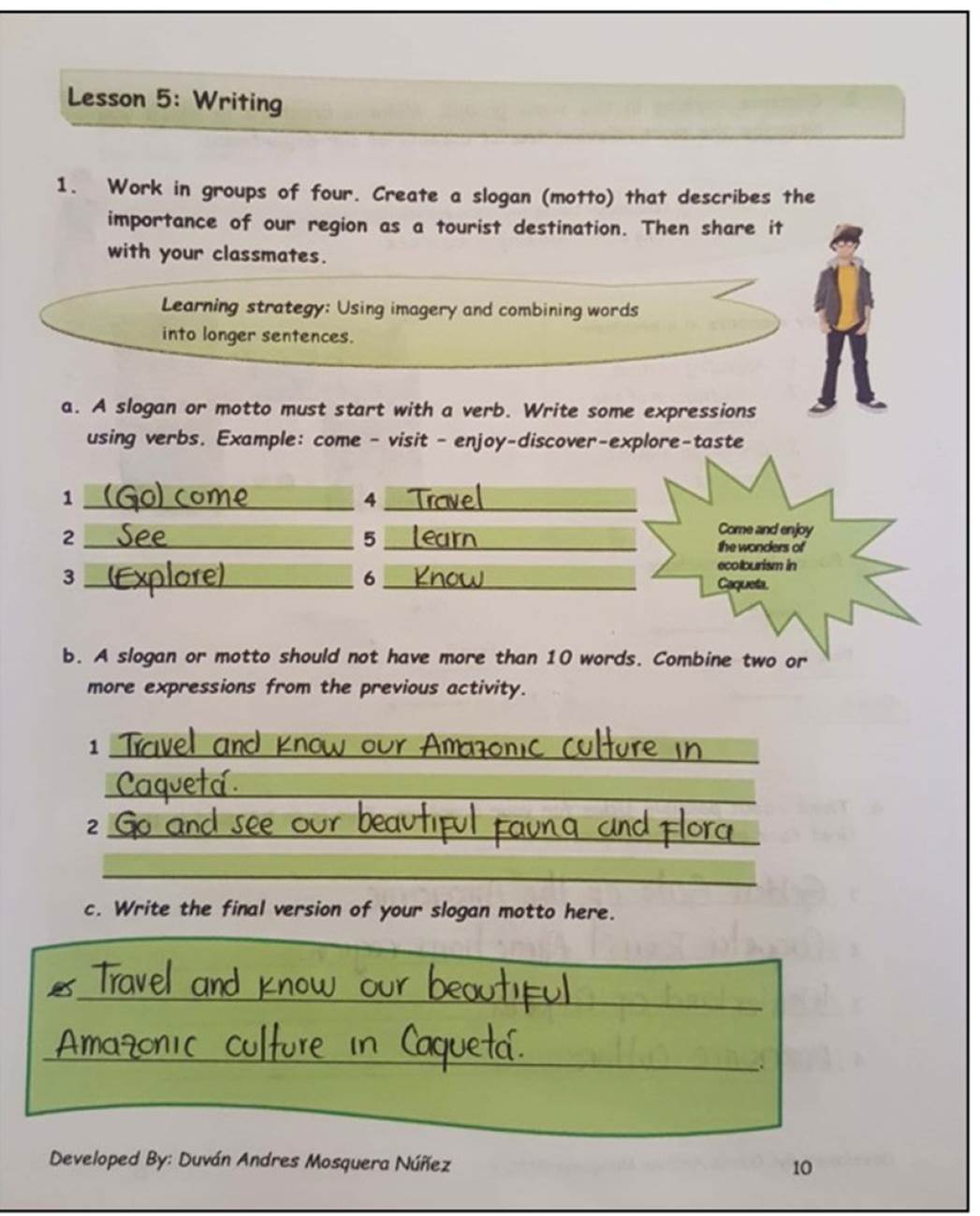

This category presents evidence of the development of the students’ writing skills featured by two recurrent patterns: working cooperatively and using the process approach to writing, which includes giving and receiving feedback. Specifically, the writing skills fostered during the implementation of the teacher-made materials are related to eliciting ideas, creating sentences, joining sentences in a coherent way, and producing short compositions. Alternatively, working cooperatively appears to be the strategy for completing most of the writing activities that required peer support.

In doing so, learners had the chance to brainstorm ideas in their groups, organize them into sentences, and finally join them coherently. With respect to this, Elbow (1981) suggests the following: “Find each idea in your best bits of raw writing, force yourself to summarize it in a sentence that asserts something, then put those sentences into the order that tells the most coherent story” (p. 130). Additionally, the process approach that informs the workshop is a scaffolding that facilitates the written assignments, thereby fostering the students’ writing skills. Due to the process approach and the constant feedback learners were exposed to, the writing skill of producing short compositions was fostered at a high level with learners completing the writing activities accurately.

Enhancing Writing Skills through Cooperative Work. This subcategory highlights the influence of cooperative work in enhancing the students’ writing skills throughout the teacher-made workshop. Cooperative work is the main methodological approach at the institution where the pedagogical intervention was implemented. This allowed students to support each other in the completion of the writing activities and to work faster and more accurately. According to Slavin (2014) , cooperative learning facilitates the structuring of group interaction and the achievement of learning goals by working in small groups in which students support each other to complete an assignment. Thus, cooperative work was the strategy chosen to encourage students to work together to achieve better results and enhance their writing skills while completing the written activities proposed in the workshop.

Furthermore, though the implementation of cooperative work, students were able to make their own contributions to the group (brainstorm ideas, create sentences, join them together coherently), ultimately achieving the goal of the writing activity (creating a short composition). Thus, working in groups enhanced the students’ writing skills by improving their ability to generate opinions and ideas, which they shared with their classmates within their groups (See Figure 3). Slavin (2014) believes that cooperative learning generates social cohesion in the pursuit of learning goals. Therefore, it is important that the members of the group interact and depend on each other to complete the writing activities suggested in the teacher-made workshop. Overall, it was evident that students enjoyed working in groups throughout their writing lesson.

Building the Writing Experience Via the Process Approach. This subcategory demonstrates that the students’ writing experience was achieved through the process approach, with special emphasis on feedback. The students were aware of the nuances entailed in the process approach to enhancing writing, rather than favoring it as a product. Thus, they were expected to work following a series of cognitive procedures to complete the writing activities. In this sense, Kroll (2001) affirms that learners “are not expected to produce and submit complete and polished responses to their writing assignments without going through stages of drafting and receiving feedback on their drafts” (p. 220). This approach helped students feel at ease when working on the proposed writing assignments, as a result of undergoing a process of generating ideas, joining them together coherently, and editing and polishing what they have written to complete the assignment.

In addition to following cognizant procedures to create short compositions, the students were given the opportunity to exchange feedback, allowing them to correct, adjust, enrich, and polish their writings. During the implementation, the students underwent the experience of not only receiving the teacher’s feedback, but also peer feedback to attain better writing. Both teacher and peer feedback were crucial in helping students achieve the objectives of each writing activity proposed in the workshop. Accordingly, learners perceived feedback from peers and from the teacher as a pedagogical strategy to foster their writing skills.

There is a strong connection between the process approach and the feedback suggested in the writing activities. Correa et al. (2013) affirm that “feedback on writing is the information or comments given by a reader to a writer in relation to organization, ideas, and writing mechanics. It is also a useful tool for writers in order to achieve their purpose” (p. 152). All in all, the process approach with its corresponding feedback enhanced the students’ writing skills since it identified and assessed the mistakes that needed to be corrected and overcome in the writing assignments.

Conclusions

Suitable and effective language learning materials should be informed by an MD rationale that considers Second Language Acquisition (SLA) principles (Tomlinson, 1998), and a scaffolding or theoretical framework (Núñez & Téllez, 2009; Núñez et al., 2009; and Núñez et al., 2012). Furthermore, it is necessary for teachers to be theoretically informed about the nature of the language (Tudor, 2001) and an EFL methodological approach (Rico, 2005). In this way, informed materials are responsive to the genuine needs and profiles of the students within their learning contexts.

Referring to the first research category, exposing the students to informed teacher-made materials that contextualize content anchors language learning and use. The students showed a positive response towards the attractive presentation of the workshop, its appealing content, the range of varied activities it included, the opportunities to communicate in oral and written forms, the use of learning strategies, and the opportunities to provide and receive outcome feedback from the teacher and peers. Correspondingly, the learning activities in the materials were perceived as relevant and useful by the 10th graders, not only making them feel at ease and raising their confidence (Núñez & Téllez, 2009), but also getting them involved emotionally and mentally (Tomlinson, 2003). Therefore, exposing students to informed materials, especially with contextualized content and activities, served the purpose of meeting their profiles and needs, facilitated the process of language learning and use, supported students’ self-investment to encourage them to work on the completion of the suggested learning activities, and helped them become aware of their own language learning process.

Regarding the second research objective, personalized local experiences became a key source for meaningful learning. The inclusion of personalized and local experiences contributed to the completion of the activities in the workshop in a meaningful way. Thus, students were especially committed to the implementation of these kinds of materials since the information provided directly referred to their personal and local context and experiences. Correspondingly, Ausubel and Fitzgerald (1961) stress the importance of relating previous cognitive experiences to what is being learnt to achieve meaningful learning. Hence, the core of meaningful learning is the result of the exposure to the local information and the opportunities provided to recall personalized experiences during the completion of the learning activities, which served as the basis for meaningful language learning and use.

With respect to the third research category, writing was achieved through the process approach and cooperative work. These two recurrent patterns with a strong emphasis on feedback facilitated students’ awareness of their own writing process. Cooperative work promoted constant interaction and support from the members of the group, involving them in the completion of the writing activities (Adams, 2013) and helping the students to enhance their writing skills. Indeed, cooperative work was an effective teaching approach that fostered language learning while the process approach allowed the students to do constant revisions of the ongoing writing activity.

Overall, the students became aware of the procedures entailed in the completion of their writing activities such as generating ideas, building sentences, connecting them, and finally, producing short compositions. Feedback as part of the process approach also played a vital role in creating spaces for learner-learner and teacher-learner interactions to build, edit, and polish the writing assignments.

Limitations

During the implementation of this research study, the main limitations were related to the lack of time that students could devote to completing the learning activities in the teacher-made materials; some of them had to be completed under time restrictions. Likewise, it was difficult to fully identify students’ cultural backgrounds to complement the design of the materials. Some learners ignored their individual relationship to the regional culture, which impeded working within a framework of meaningful experiences. Finally, most of the students were not used to completing writing activities that demanded a more significant time investment.

Questions for Further Research

Considering the findings and results of my research study, I have formulated two research questions for further research: How can the design and implementation of teacher- and student-made materials, founded on community-based pedagogies, foster students’ local and cultural awareness? How can the design and implementation of teacher- and student-made materials based on the use of L1 promote intercultural skills in EFL learners?