Introduction

Colombia has embraced continuous improvement in education to keep pace with the changing nature of societies. As a result, educational institutions are seeking high-quality programs that can be internationally benchmarked. This commitment is evident in the growing adoption of international curricula, such as the International Baccalaureate Organization(IB), the Cambridge Assessment International Education (CIE), and the College Board Advanced Placement Programs (AP), as well as the accreditation from international bodies like the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM), the Council of International Schools (CIS), and the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS), and national accreditation (ISO 9000) programs for K-11 schools across Colombia.

This study emerged from the necessity to identify teachers’ perceptions about the implementation of the Content and Language Integrated Learning (hereafter CLIL) approach with young learners at private educational institutions in Bogota, Colombia. To achieve this goal, a mixed-methods approach was used, combining qualitative and quantitative data collection methods to investigate teachers’ perceptions regarding CLIL implementation (Hinds, Vogel, & Clarke- Steffen, 1997).

This study collected data from private schools (n=10) in Bogota, Colombia, in order to identify teachers’ beliefs and perceptions about the CLIL approach and its implementation. The study is grounded on the principle that all individuals involved in the CLIL ecosystem should be considered, with a particular emphasis on the experiences of practitioners, as they have first-hand knowledge about the implementation process from diverse angles. The literature suggests that teachers are still unfamiliar with the CLIL approach in Colombian educational sectors (Guzman, 2008), and there is a lack of representation of teacher voices. Curtis (2012a) claims that before implementing the approach, “it is mandatory to hear the voices of teachers, considering that teachers are the key stakeholders in any educational endeavor” (2012a, p. 1).

Furthermore, there is a lack of context-oriented CLIL professional development programs, which are crucial for a successful implementation. In this regard, Pistorio (2009) claims that the most salient factor when implementing CLIL should be teachers’ training programs concerning their competencies. Moreover, CLIL implementation demands significant preparation, planning, and the development of human and material resources, as well as administrative and institutional support (Anderson, McDougald, & Cuesta Medina, 2015). The role of school administrators is crucial in ensuring the successful implementation of CLIL, particularly as they have access to both human and non-human resources, and a clear understanding of institutional goals. This study contributes to the existing knowledge on CLIL implementation, not only in capital cities like Bogota but it also provides insights into the bilingual education community throughout Colombia. Thus, the research question “What are the teachers’ beliefs and perceptions regarding CLIL in Bogota, Colombia?” brings forth the voices of practitioners who have valuable insights into combing content and language across diverse teaching environments.

Review of Literature

This section addresses the most important theoretical constructs related to the current study. In addition, it presents a short report on previous similar studies related to CLIL implementation in Colombia, such as CLIL and young learners, teacher perceptions, and teacher training framed around CLIL.

A look at CLIL and the 4Cs

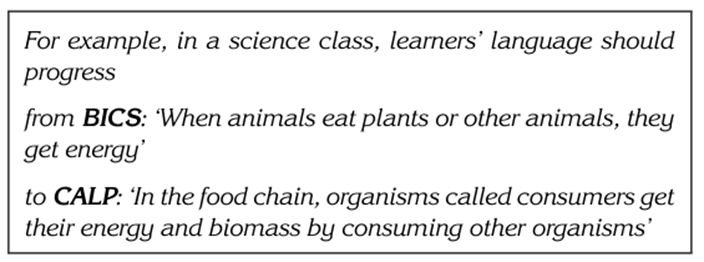

The term “CLIL” (Content and Language Integrated Learning) was coined in 1994 by David Marsh and Anne Maljers (Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010; Dale & Tanner, 2012; Pinner, 2013) to describe lessons related to “the experience of learning non-language subjects through a foreign language” (Marsh, 2012, p. 141). Considering this, CLIL is an approach where content and language learning are characterized by their focus on developing cognitive strategies for learning new content through a foreign language (Cenoz, 2015; Dalton-Puffer, 2011; Halbach, 2012). This type of approach is understood as an educational model that allows students to interact with the target language in foreign language classrooms, using the language as the vehicle for content transmission with a general focus on meaning and occasional attention to form (Dalton-Puffer, 2011). As a result, CLIL has become a viable approach for bilingual teaching curriculums through the implementation and integration of four different principles, also known as the 4Cs, i.e., Cognition, Communication, Content, and Culture. Coyle et al. (2010) describe these principles as follows: cognition is the process of “thinking about thinking”, which sets out to develop metacognitive skills to construct an understanding of the content; communication is the vehicular language used to construct new knowledge, developing the two necessary language skills to interact in any given context (Brown, 2006). The fists skill is known as Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skills (hereafter BICS), which represent the communicative capacity that learners acquire in daily interpersonal exchange, where the context is embedded. BICS usually take an average of 1-3 years to develop, and this process is largely dependent on the social groups that learners belong to. At this stage, learners appear to speak English but often struggle with the academic English register (Anderson, 2011; J. Cummins, 2000; Halbach, 2012; Ranney, 2012). Some examples of basic conversational fluency with BICS include situations such as buying food, asking for directions, social situations, and even class discussions in some cases students develop strategies to communicate. Learners can sound like native speakers, especially if they have developed the use of idioms and backchanneling uh-huh, hmmm. Uh-uh, etc. (Jim Cummins, 1999; Khatib & Taie, 2016). The second language group of skills is Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (hereafter CALP), which allows learners to manipulate language features to deal accurately with academic language where the context is reduced (Anderson, 2011; Cummins, 2000; Ranney, 2012). In this group, content is understood as the knowledge and skills learners will need to acquire. Moreover, it involves understanding and using formal language about curricular subjects, including explaining the possible results of an experiment and providing reasons for performing calculations. Nevertheless, some researchers (Jim Cummins, 2009; Dicker, Chamot, and O’Malley, 1994; Halbach, 2012; Khatib and Taie, 2016; Várkuti, 2010) claim that learners take anywhere from five to seven years to develop CALP. Learners start developing BICS when they start programs that combine content and language, such as CLIL, then progressively advance toward CALP, as seen below in Table 1.

Culture, on the other hand, is where learners can find different uses of language and explain how culture is involved in exploring the links between language and their cultural identity. Culture in CLIL is inherently integrated into every theme or topic, thereby going beyond the “national” or even the “ethnolinguistic” culture to incorporate other spheres of interaction (professional, subcultural, etc.) (Lin, 2015; D. Marsh, Maljers, & Hartiala, 2001). In the context of CLIL, culture encompasses self-awareness, understanding of others, identity, citizenship, and the development of pluricultural understanding and intercultural competence. However, it is often misconstrued as merely engaging in superficial celebrations of festivities and holidays.

CLIL in Colombia

Overall, CLIL is an educational approach that claims to increase students’ foreign language proficiency without taking up additional time in an already crammed curriculum (Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2009b). Currently, there is an array of schools, mainly private and a few public, in Colombia that are adopting and adapting this educational approach to increase students’ second language proficiency (Curtis, 2012b; Otálora, 2009; Salamanca & Montoya, 2018), while others are using the approach for increased success in content area subjects (Aguilar Cortés and Alzate B., 2015; Cano Blandón, 2015; Quazizi, 2016; Quintana Aguilera, Restrepo Castro, Romero, & Cárdenas Messa, 2019). By introducing both content and language simultaneously, students could potentially find their focus split between trying to understand the content and trying to comprehend the language (Graham, Choi, Davoodi, Razmeh, & Dixon, 2018). Along the same lines, language teachers are self-confident when using the target language, but they strive to convey content effectively. Accordingly, professional development and teacher training programs must be designed to face these content-language challenges (Cammarata, 2010; Coonan, Favaro, & Menegale, 2017; Hunt, 2011; Tatzl, 2011; Vilkancienė & Rozgienė, 2017). As a result, teachers often encounter difficulties when addressing and assessing students regarding both “content” and “language”. According to Sweller’s, (1988) Cognitive Load Theory, cognitive resources can be overloaded during learning tasks when learners find their focus split between disparate sources of information related to a learning goal. CLIL diminishes this issue by evenly addressing both content and language, so that learners get into the habit of using the language for a real purpose while immersed in the content.

CLIL and Young Learners (YLs)

The benefits of the CLIL approach not only offer an opportunity for young learners (YLs hereafter) to develop their language skills and acquire knowledge in content-subject but it also enhances their developmental process of intercultural knowledge (Divljan, 2012). Considering the Colombian educational system, young learners are categorized in four groups: initial education (preschool), primary education, (1- 5 grades), and secondary school (6 to 11 grades). Furthermore, when acquiring a new language in bilingual education, young learners are benefitted as content and language can foster student interest and motivation, which are two essential elements required for effective learning (Anderson et al., 2015; Hasselgreen, 2013; Ioannou-Georgiou & Pavlou, 2011).

Therefore, in bilingual institutions, students are immersed in a communicative language teaching context that enhances their likelihood of acquiring the foreign language, leading to increased opportunities to develop Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skills (BICS). Nevertheless, learners still face challenges in developing Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP) to understand subject-specific content using the target language (Ioannou-Georgiou & Pavlou, 2011). Unfortunately, the lack of evidence of CALP proficiency is a common issue in bilingual environments.

CLIL, as a dual-focus approach, allows young learners (YLs) to immerse themselves in a context that enhances their development of critical thinking skills (Edelenbos, Johnstone, & Kubanek, 2006). Therefore, bilingual education for YLs requires the implementation of curricula that integrate language and content standards, promote learners’ confidence and motivation, and provide teachers with the necessary support to ensure successful learning processes (Dale & Tanner, 2012). Thus, the CLIL approach has proven to provide YLs with a context-orientated solution to enhance both content and language development.

Is Teacher Training Needed for CLIL Implementation?

The competencies that CLIL practitioners need to possess are not far from what bilingual educators should have, which corresponds to knowing how to incorporate the correct method, approach, or strategy in the classroom. CLIL is considered an umbrella term that describes both learning an additional language and the learning of non-language content (Coyle, 2008). Furthermore, CLIL addresses the needs of modern learners by supporting communicative and cognitive development, helping them access, analyze, assimilate, work with, and create information (content) using multiple languages (Coyle, Hood, et al., 2010). Therefore, teachers-practitioners should have the necessary competencies and skills to successfully deliver content and language classes.

Target competencies are the competencies teachers or practitioners should acquire through professional development or teacher training programs (Marsh et al., 2011). All of these competencies learning, educational, social, and technological are essential for ensuring quality teaching, not only for CLIL teachers but for education as a whole. On the other hand, other competencies language proficiency, attitudes, content knowledge, linguistic knowledge, cultural knowledge, and teaching knowledge are more specific to the CLIL approach. Nevertheless, CLIL was coined by incorporating the most successful approaches and methods in education and language learning (Coyle, Marsh, & Hood, 2010).

Although the CLIL approach has gained presence in Colombia in the last decade (Curtis, 2012b; McDougald, 2009; Rodriguez Bonces, 2012; Rodríguez Bonces, 2011), it is still relatively novel in the field of education as a whole, being primarily known among bilingual practitioners. However, challenges such as the lack of appropriate and authentic material, inefficient training programs (McDougald & Pissarello, 2020), poor coaching (Murillo-Caicedo, 2016), and language and content balance regarding implementing CLIL (Cano Blandón, 2015; Catenaccio & Giglioni, 2016; Corrales, Paba Rey, Lourdes, & Escamilla, 2016) are still at the forefront of academic debates throughout the country. These challenges place demands on schools and teachers for academic success in bilingual environments. The underlying factor that has contributed to these challenges is still the lack of practical knowledge regarding pedagogical principles. In essence, a lack of professional development programs tailored for in-service and pre-service teachers (McDougald, 2015; McDougald & Pissarello, 2020; Torres-Rincon & Cuesta-Medina, 2019) needs to be addressed so that practitioners can benefit from them. Moreover, CLIL-oriented lessons should be carefully planned and outlined so that both content and language goals are achieved, and context-oriented teacher training programs are ideal for this purpose. Therefore, before venturing into this crusade incorporating CLIL strategies in the classroom, it is important to closely examine whether the institution, teachers, and, most importantly, students are equipped to introduce CLIL, and if so, which model should be adopted?

Considering this key factor, CLIL feasibility-implementation, literature continues to highlight that most Colombian teachers are not prepared to fully assume CLIL as a major feature of their classes (McDougald & Pissarello, 2020; Pérez Cañado, 2016b; Torres-Rincon & Cuesta-Medina, 2019; Vilkancienė and Rozgienė, 2017). Furthermore, Hadj-Moussová, Hofmannová, & Novotná (2001) , and Pistorio (2009) affirmed that the most salient factor when implementing CLIL should be teacher training programs aligned with their competencies. Accordingly, teacher training programs should be introduced and systematically intertwined with ongoing local training plans to enhance the implementation of content-based approaches. Subsequently, coordinators and other members of the educational community should receive training as well, (Murillo-Caicedo, 2016; Torres-Rincon & Cuesta-Medina, 2019). Implementing CLIL demands time and serious considerations, including families’ backgrounds, students’ interests, age, abilities, needs, and so forth. All of these are operational variables that educational institutions often do not consider when including educational approaches that aim to combine language and content.

Moreover, implementing a CLIL-oriented solution requires developing a curriculum that pays serious attention to the balanced integration of content and language. However, the CLIL approach to the curriculum is inclusive and flexible, as it encompasses a variety of teaching methods and curriculum models and can be adapted to learners (Coyle, Holmes, & King, 2009). CLIL implementation in Colombia has been difficult to track and document since there is a blurred line that exists between bilingual program implementation (Dewaele, Wei, & Beardsmore, 2003) and quality bi/multi education, which includes several aspects that resemble a CLIL approach, yet schools do not claim that they are using CLIL. Notwithstanding this, schools that have incorporated CLIL assert that higher cognitive stages or critical thinking and acquisition of new competencies are some of the benefits discovered (Mariño, 2014). It is challenging to accurately pinpoint the most relevant advantages seen in Colombian schools that have implemented one of these approaches or have incorporated some strategies or techniques related to them. This is due to the pedagogical principles and both national and international standards of each school, which in turn significantly varies from one school to another, thereby affecting the traceability of how CLIL is implemented in private schools in Bogota. One of the primary challenges in implementing CLIL is determining the starting point, and this is where teacher training becomes crucial. Curtis (2012b) highlights the importance of hearing teachers’ voices before implementing the approach, recognizing that teachers are key stakeholders in any educational endeavor and are instrumental in driving educational change.

Teacher´s perception of CLIL

It is crucial to understand the diverse beliefs held by teachers regarding the integration of content and language in teaching and learning processes, and how these beliefs impact the successful implementation of CLIL pedagogy. Teachers’ attitudes and beliefs around CLIL implementation varies based on their teaching experience delivering content and language, access to teacher training programs, as well as context and curricular variations that the CLIL approach offers. Although research on CLIL implementation is scarce in Colombia, there has been an increase in CLIL-oriented or bilingual programs throughout the country, leading to a growing body of studies that highlight the challenges faced by practitioners. For example, Torres-Rincon & Cuesta-Medina (2019) discuss the limitations of lesson planning in CLIL environments, while other studies emphasize the gaps resulting from limited teacher training programs (Pérez Cañado, 2018, 2020) and the lack of administrative support, collaborative spaces, and support mechanisms for both L1 and L2 students and teachers (Coyle, 2018; Kim & Lee, 2020; McDougald & Pissarello, 2020).

As CLIL is context-oriented the approach will continue to grow, expand, change, and mold itself into different educational environments. Consequently, there will always be opportunities for improvement, which in turn creates gaps for researchers to explore. So far, the overall perception of CLIL has been mainly positive (Banegas et al., 2020; Czura & Anklewicz, 2018; McDougald, 2020; Salvador-García et al., 2018; Vilkancienė & Rozgienė, 2017), with increased motivation for both teachers and students, better classroom results, diversity in materials and overall quality in content delivery.

Methodology

This section will provide information on the instruments utilized in this study for data collection, as well as on context, and participants. This mixed-methods approach allowed the researchers to explore to what extent the participating teachers from selected private K-11 educational institutions in Bogota, Colombia, were equipped to implement CLIL strategies in their classroom settings and to analyze data holistically. By collecting data from two questionnaires, structured and semi-structured interviews, and registering information in a research logbook, researchers were able to identify the “knots and bolts” teachers are using to successfully incorporate CLIL principles in their lessons considering the Colombian context. Therefore, with 10 participating schools and 150 teachers throughout Bogota, researchers gathered significant data that allow for the identification of the main challenges teachers are facing, while establishing some potential solutions in further research.

Research Design

The present study was undertaken within the context of a mixed-method approach used to research how CLIL is implemented in K-11 schools (n=10) in Bogota, Colombia, in which more than 50% of the subjects at the primary or secondary level are taught through a target language. This approach combines quantitative and qualitative methods, allowing for a balance of their respective limitations and leveraging their strengths. Additionally, this research approach provides stronger evidence and increased confidence in the findings by employing both inductive and deductive thinking (Burns, 2009; Creswell, 2013; Leavy, 2017).

To address the research question, the study also applied an explanatory sequential mixed-method design (Creswell, 2014). The qualitative aspect of the study also followed the grounded theory design, which facilitated the “progressive identification and integration of categories” (Barak & Usher, 2019, p. 5) emerging from the data. Questionnaires and structured and semi-structured interviews along with a researcher’s journal were used to gather information that allowed for a better understanding of bilingual teachers’ perception of CLIL and its implementation in the participating private schools in Bogota, Colombia. The digital researcher’s journal or notes were essential in summarizing key points and asking additional questions that emerged along the way, thereby connecting that information to the research question and additional sources used, while allowing all researchers to contribute and share thoughts using Google Keep. Overall, the strategy of making use of and incorporating the researcher’s notes was crucial in helping researchers to read the data analytically and critically.

Context and Participants

The study was conducted in Bogota, Colombia, involving 121 teachers from ten private schools. These schools were selected based on their use of international curriculums and their claim of incorporating the CLIL approach to integrate content and language, thereby reinforcing their bilingual education approach. During data collection through interviews and focus groups, the participating schools were specifically asked about the approach or method employed in their bilingual education program. The information gathered about these methods and approaches was instrumental in determining the schools’ eligibility for participation in the study.

The schools included in the study can be described as upper-middle-class institutions, and the English proficiency of the participating teachers ranged from B2 to C1 according to the Common European Framework of Reference (Council of Europe, 2018). Researchers personally contacted the participants and provide them with a succinct explanation of the research topic and their role in the study. The participants, aged between 25 and 50 years old, mostly (65%) held undergraduate degrees in Modern Languages or English Language Teaching. Currently, all participants were teaching various content subject areas such as mathematics, science, social studies, Information-Communication-Technology (ICT), Literature, and English. A large majority (82%) of the participants had been self-contained teachers for more than 3 years, while some of them (18%) had extensive experience teaching these subjects but were not familiar with CLIL principles as they considered it a relatively new concept.

Ethical considerations

To carry out the study, school academic coordinators and English area leaders were contacted to obtain consent to apply the questionnaires with the bilingual teachers of the institutions. After receiving permission to administer the instrument in the schools through informed consent, the research was presented to the entire teaching staff comprising 196 teachers. Out of these, 150 teachers volunteered for the study, but only 121 teachers ultimately participated. Therefore, with oral consent (Burns, 2009), they were provided with a detailed description of the potential benefits their participation would have to society. Additionally, they were provided with an explanation of the tasks they would be undertaking and the duration of their involvement (answering questions through questionnaires and interviews), an explanation regarding the protection of their privacy, as well as instructions on how to obtain a copy of the results. Moreover, the teachers were informed about how to contact the researchers for further information, if needed.

Instruments

Two questionnaires (Q1: How CLIL are you?) (Q2: CLIL teachers’ perceptions, attitudes & experiences on implementation, as shown in Appendix 1) were effective tools for gathering information regarding beliefs and perceptions from the participants (Rowley, 2014). Both questionnaires were delivered online using Google Forms. The first instrument Q1 was structured into six categories: the first one related to how teachers activate learner’s previous knowledge; the second category was about the guidance provided by the teacher to facilitate learners’ understanding; the third, fourth, and fifth categories focused on language, speaking, and writing; and the last one was directly related to assessment, review, and feedback. The questionnaire used a four-point Likert scale: strongly agree, agree, disagree, and strongly disagree, which helped measure the frequency of implementation of each of the statements presented about the CLIL approach.

On the other hand, the second instrument Q2 was divided into 10 closed-ended questions. Four of the items were factual questions proposed to identify who the participants were. The other six items were attitudinal questions (Burns, 2010) intended to identify current challenges bilingual teachers face every day and the feasible support teachers need to hone their CLIL teaching practices. Allowing teachers to express themselves was pivotal, as they serve as the primary source that underpins the main findings, thereby making it possible to identify the teachers’ perceptions (challenges and opportunities) when implementing CLIL in a Colombian educational context.

The structured interviews (n=6) allowed researchers to follow up on and confirm data that emerged from the questionnaires, which were key elements in CLIL implementation. The participants were selected voluntarily from the teachers who initially responded to the questionnaires. All teachers worked at different participating schools. The structured interviews were recorded and later transcribed for further analysis using Automatic Speech Recognition through Microsoft Word. This tool aided the researchers with an automatic, machine-generated interview transcript, which was later edited and verified. The semi-structured interviews were not transcribed. However, at the end of each interview, a written summary was produced to capture the researchers’ perspectives on the interview as a whole. These summaries were also analyzed. The information was analyzed and organized following the questions asked, using Microsoft Excel, in which categories and subcategories were created for coding.

Data collection

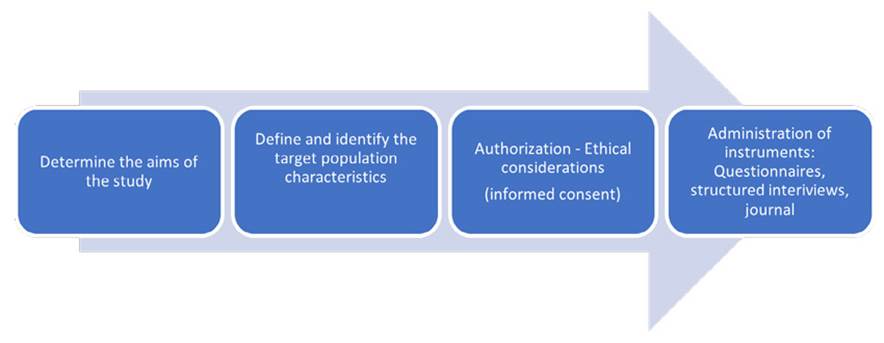

The data collected was organized and structured into 5 steps, as shown in Figure 1 (Data Collection Procedure). Firstly, the objective was determined to be researching the perception teachers have about the Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) approach. Then, selection criteria were defined to choose the most suitable populations. Afterwards and based on those criteria, participants were chosen based on their professional profile (Elementary-bilingual teachers) and contacted via email to get the corresponding permission and consent to collect the necessary data. Each one of the participating educational institutions (10 private schools in Bogota) was provided with detailed information about the study.

Data Analysis Procedure

The collected qualitative data were analyzed using the grounded theory approach (Corbin & Strauss, 2008), triangulating the data collected using the two questionnaires, theoretical framework, semi-structured interviews, and the researcher’s field notes, along with parallel phases of the study to analyze the data collected. The objective of this design was to use quantitative and qualitative approaches to study the same aspects of the research phenomena (Ponce & Pagán-Maldonado, 2015). With this in mind, the data collected was divided into five categories to better interpret and pinpoint the participating teachers’ perceptions about CLIL implementation in Colombia, and to what extent they successfully imbue their lessons with these principles. These categories are represented as follows:

Results

Challenges

The participating teachers face several implementation challenges when using a CLIL approach in their classrooms, such as lack of time, finding appropriate strategies, and not having enough knowledge to deliver content subjects. According to the participants, they were not considered for implementation of this approach at their schools. Moreover, teachers frequently struggle to find appropriate and authentic material that is tailored to their educational contexts. Similarly, a large number of teachers explicitly stated that few opportunities are allotted for activities such as round tables or collaborative discussions to share teaching strategies and methodologies, sporadic collaborative planning, and peer observation to provide effective and realistic teacher training programs as per the qualitative data collected from the question: “If you teach using a CLIL approach, please list the 3 most important challenges you currently face or have faced:”

Time to prepare materials and to share experiences with my peers. (P17, Science teacher).

Training, more flexible time to deliver content, acquisition of better material. (P26, Self-Contained Teacher, Primary).

Advice in terms of tools that facilitate the development of classes in English and simple mechanisms that allow evaluating language processes. (P36, Social Studies teacher, Secondary).

After collating the information, we can assert that educators do not feel equipped to present a robust syllabus that wisely balances language and content. Teachers claimed to crave mentoring sessions that provide fertile ground for them to craft tailored lessons according to their learners’ needs, interests, social backgrounds, strengths, and weaknesses to plan according to the nature of the ‘dream’ and the ‘dreamer’ embedding CLIL principles, which in essence is the teacher (the dreamer) who desires and hopes for an ideal teaching context that incorporates all of the CLIL principles that include appropriate materials, adequate training, and balance between language and content (the dream).

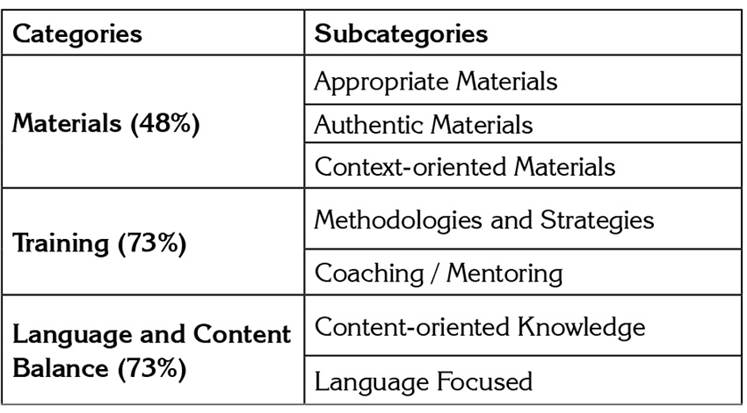

Participant teachers chose and listed the three major challenges they face when implementing the CLIL approach. As shown in Table 2, a considerable number of participants (48%) agreed that they need appropriate and authentic materials. Therefore, it is possible to assert that the type of materials for content and language learning do not overlap with the students’ context (Tomlinson, 2013). After conducting semi-structured interviews, some teachers (10%) expressed their concern about using textbooks and other materials that do not guarantee effective support to guide learners in the process of learning content and language. They also expressed concerns about adapting those materials to make them more suitable to the student’s learning context and language level.

Moreover, participants identified their need for training (73%), arguing that being updated in methodologies and theories could provide more opportunities to improve their content knowledge, teaching skills, and practices to meet the school standards (Darling-Hammond & McLaughlin, 2011). When the researchers followed up on those responses, the participants claimed that the training process in their schools and teaching contexts was carried out only to “assess and judge” their teaching practices and did not devote time to providing teachers with consistent and fruitful training programs.

Institutional support for CLIL implementation

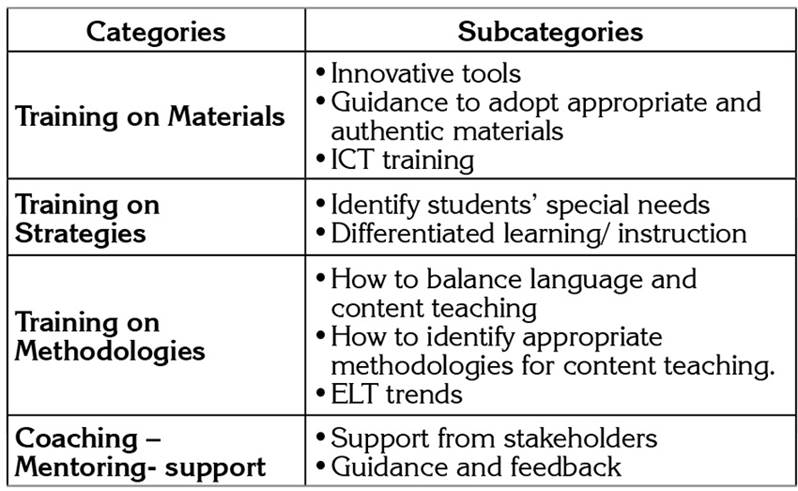

Teachers identified areas where adjustments may yield valuable outcomes in which some of these improvements stem from the challenges previously mentioned per se. In the same line of thought, teachers reported that they needed training programs along with continued professional development that would entitle them to design, implement, assess, and adjust teaching strategies that provide fertile ground to foster both language and content evenly. Yet, according to the structured interviews, a lack of the teachers’ voices has been perceived, thereby affecting to some extent the CLIL implementation at their educational institutions.

Based on the responses from the semi-structured interviews, researchers were able to determine four categories and subcategories that helped address the main concerns teachers have when referring to institutional support to implement CLIL. Participants reported having been actively engaged in the following practices related to CLIL implementation at their schools (Table 3).

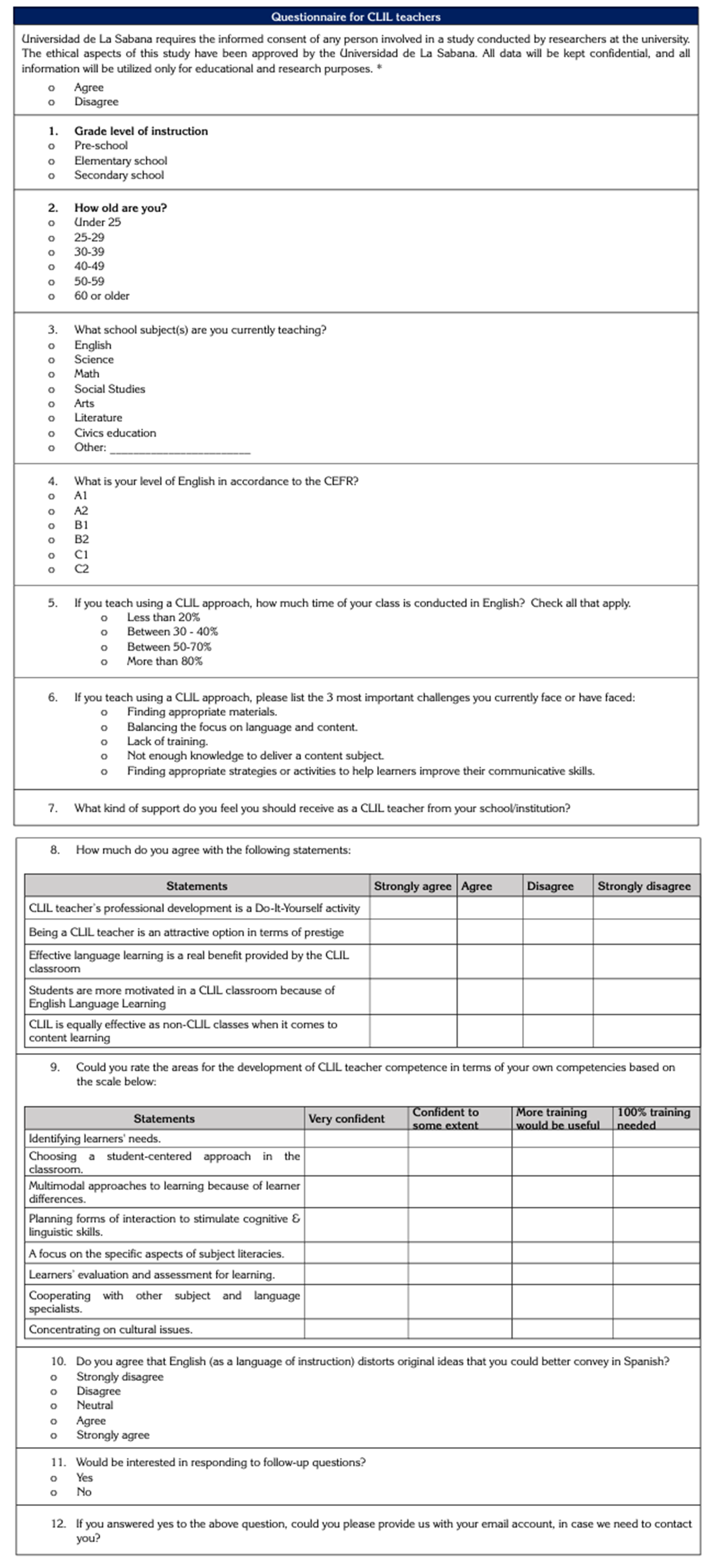

Benefits of CLIL implementation

It is a widely held assumption that CLIL presents several challenges (Banegas, 2012; Bruton, 2013; Corrales et al., 2016; Xanthou, 2011). However, it is undeniable that it also offers a significant number of benefits. In Colombia, many schools are seeking opportunities to incorporate CLIL into their curriculum to nurture language awareness, content awareness, and intercultural knowledge (Anderson et al., 2015). Figure 3 exhibits five descriptions regarding CLIL implementation. Teachers were asked to indicate the description with which they most strongly identified.

Figure 3 Note. 1. CLIL teacher’s professional development is a Do-It-Yourself activity; 2. Being a CLIL teacher is an attractive option in terms of prestige; 3. Effective language learning is a real benefit provided by the CLIL classroom; 4. Students are more motivated in a CLIL classroom because of English Language Learning; 5. CLIL is equally effective as non-CLIL classes when it comes to content learning. Benefits of implementing CLIL.

Many of the participants (65.5%) consider that CLIL engenders effective language learning. This approach fosters language awareness for subject teachers and language teachers equally. To some extent, teachers are acquainted with CLIL principles and value how it encourages learners to develop critical thinking skills (Edelenbos et al., 2006).

Even though a considerable number of participants (40%) assert that CLIL is equally more effective than other bilingual approaches when teaching language and content, teachers also consider that the methodologies and approaches that schools currently carry out for bilingual education offer relevant opportunities to students. As per the data, teachers mentioned Presentation, Practice, and Production (PPP), the Communicative Approach, CBI, and the literature-based approach, among others. Implementing CLIL in Colombia is still a challenge because of the diverse variety of bilingual programs that are employed in private schools. Notwithstanding, private schools in Colombia that have incorporated this approach claim higher cognitive stages of critical thinking and acquisition of new competencies are some of the benefits of using CLIL (Murillo-Caicedo, 2016). Accordingly, it can be asserted that the participants recognized CLIL as a beneficial teaching approach because it not only enhances language and content, but also fosters critical thinking skills, metacognitive skills, and problem-solving skills.

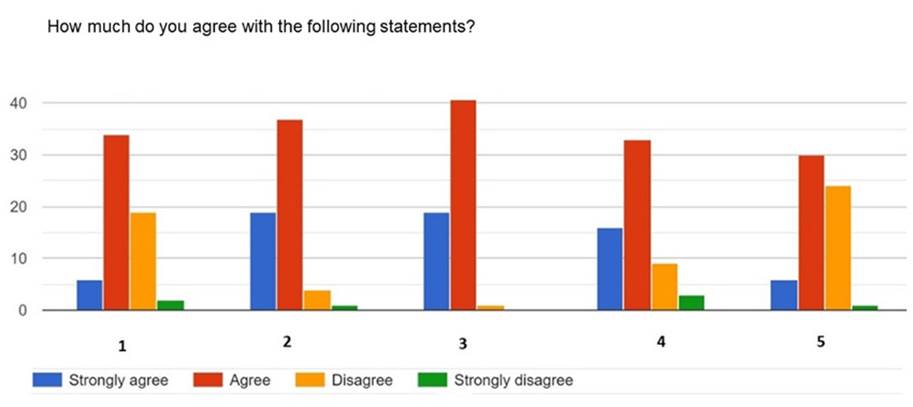

CLIL Competences

This section outlines the CLIL competencies, as mentioned in the “Literature Review”, that teachers consider fundamental in the construction of a rich CLIL learning environment. The competencies described in the descriptors of Figure 4 need to be further situated in specific contexts to be addressed explicitly. Teacher participants were asked to rate the areas for the development of CLIL teacher competence. Participants choose their level of proficiency in managing the following CLIL principles using the eight descriptors below (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Note. 1. Identifying learners’ needs; 2. Choosing a student-centered approach in the classroom; 3. Multimodal approaches to learning because of learner differences; 4. Planning forms of interaction to stimulate cognitive & linguistic skills; 5. A focus on the specific aspects of subject literacies; 6. Learners’ evaluation and assessment for learning; 7. Cooperating with other subject and language specialists; 8. Concentrating on cultural issues. CLIL competences

As per Figure 4, there was a greater variety in the perceptions of the participants concerning their level of confidence in applying CLIL principles. Regarding positive attitudes, teachers feel assured on topics such as identifying learners’ needs (91%), choosing a student-centered approach in the classroom (90.2%), planning forms of interaction to stimulate cognitive and linguistic skills (69%), and focusing on the specific aspects of subject literacies (70.5%). However, most of the participants agreed they need more training in statements like multimodal approaches to learning given learner differences (46%), learners’ evaluation and assessment for learning (42.6%), and concentrating on cultural issues (52%).

Based on the above findings, it can be concluded that the participants have blurred notions when implementing CLIL principles. Most teachers consider that being a self-contained teacher entitles them to successfully deliver CLIL lessons, but they have second thoughts, as they are not familiar with the literature on the subject. Mostly, their perceptions are based on their class experiences. Thus, many of them request further assistance to fully understand the guidelines that bolster this approach. After collecting data, several findings related to areas in which teachers urge guidance were identified. Firstly, teachers need strategies to cater to different learning styles considering the students’ linguistic, cognitive, and social skills. Secondly, the participating teachers deem that the assessment process is weak and there is room for improvement that might be provided by constant and consistent coaching (Leal, 2016). Lastly, teachers assume that they need more pedagogical tools to successfully embed the curriculum with cultural aspects (Curtis, 2012b).

Language vs Content

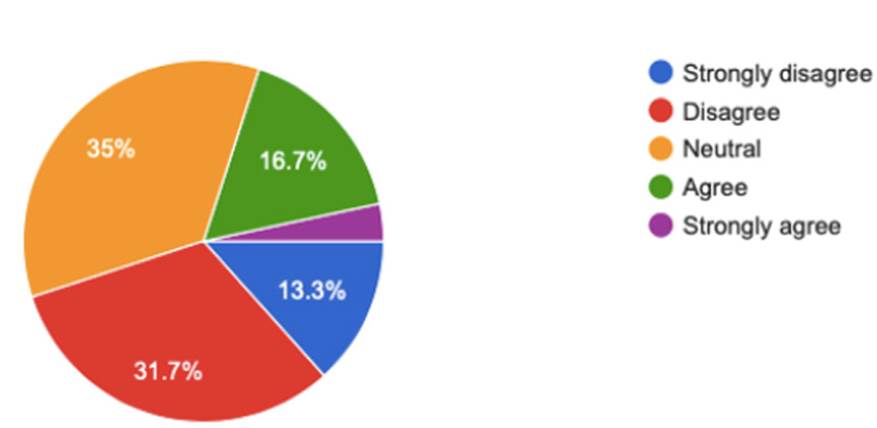

Do you agree that English (as a language of instruction) distorts original ideas that you could better convey in Spanish?

According to Figure 5, it appears that a significant proportion of teachers (35%) adopted a neutral position to determine to what extent content is distorted due to the implementation of a second language (English). As a result, it was deemed necessary to conduct interviews to pinpoint and help triangulate the teachers’ perceptions regarding the inextricable relation between language and content in CLIL scenarios. Participants (P) stated their insights and shed light on the subject as seen from P22. “In some specific cases, I need to translate with some students to verify their understanding because they have serious difficulties with the language but not with the concepts worked in Science”. (P22, Third grade)

Teachers realized that students struggle to decode some words or utterances in English which diminishes their attention to content. Learners find it challenging to present their worldview in the target language and constantly need to use their L1 to do so (Graham, Choi, Davoodi, Razmeh, and Dixon, 2018). Moreover, there is a lack of confidence that undermines the teachers’ beliefs in their communicative skills, which compels them to use their mother tongue.

This lack of confidence was evidenced in several participants as expressed below by participants 5 and 53. “I am a mathematician and even though I can speak English very well, I usually struggled when providing explanation about the procedure students need to follow when solving problems that involved various steps and algorithms”. (P5, fifth grade). “I try my best all the time, but sometimes it is just impossible. My little kids required Spanish to better understand the instructions, because if the instruction is not clear they will not be able to achieve the goal”. (P53, second grade)

As noted from the questionnaires and the structured interviews, teacher participants still encounter difficulties in addressing and assessing students regarding both “content” and “language”. They consider that the students’ focus is split and sometimes cannot find a clear directrix to assess either language or content or both (Sweller, 1988). In consequence, CLIL diminishes this issue by evenly addressing both content and language, evidenced through clear planning, scaffolded activities, and communicated assessment practices that balance both content and language.

Discussion

The results of our study provide us with different kinds of evidence on the various issues related to CLIL implementation in Bogota. In our attempt to provide a valid interpretation of these results, two main contributions emerge from this study. Firstly, the study set out to understand how 121 bilingual teachers in Bogota, Colombia, are trying to implement a content and language approach in their institutions. This allowed us to gain a better understanding of the underlying factors associated with CLIL implementation, and the data tells us that with this approach, there are still a few “gray” areas when it comes to successfully combining language and content. Secondly, the study unveiled that the participating schools are using context-oriented resources, to provide real solutions, to their teaching context. Considering that schools were mainly attempting to replicate a “foreign” version of CLIL without clearly thinking about the consequences and or needs of their learners, which in turn can be related to the lack of CLIL teacher professional development programs available. Furthermore, the fact that their voices were not being heard or considered as part of the implementation process also affected the teaching and learning process (Torres-Rincon and Cuesta-Medina, 2019). Time and time again, professional development programs on content and language-integrated learning are drawn into the debate on CLIL (Pérez Cañado, 2016b; Vilkancienė and Rozgienė, 2017). Yet, few schools have incorporated the “teacher or practitioner” as a resource.

Furthermore, in terms of implications, the results from this study provide insights for not only the Colombian ELT (English Language Teaching) or CLIL community but also the regional, Latin American ELT community so that they can become aware of issues related to CLIL implementation. For starters, empowering practitioners to adapt successful CLIL practices into their own learning environments, where learners and their context are at the forefront (Alcaraz-Mármol, 2018; Catenaccio & Giglioni, 2016; Massler, 2012). Additionally, this study also provides decision-makers with evidence as to the importance of involving teachers in the implementation, using their voices as one of the primary resources in making the CLIL approach a reality for their institutions.

Nevertheless, this study also has limitations, taking into consideration the number of participating teachers in the study, future studies with a larger sample would be beneficial. The results from the study did not report on the other stakeholders in the CLIL ecosystem, such as learners, parents, and administrators, who also play a significant role in the implementation process. This is because administrative support is an essential part of ensuring that the tools, resources, and overall goals of the institution are met. Practitioners should lean more on a “top-down” approach to implementation, where communication, teamwork, and collaboration are priorities, as opposed to the “bottom-up” approach where the participants within the educational community have isolated initiatives that only affect a few teachers’ classroom practices and not the whole.

As a recommendation for future analysis to studies, it would be beneficial to (a) incorporate or involve teachers and/or practitioners from the beginning of the implementation process, generating global institutional goals for content and language integration, (b) establish clear objectives for CLIL professional development programs since this approach comprises of diverse ways of working and teaching, thereby introducing teachers to new elements, and (c) constant communication with all stakeholders is essential so that all those involved understand the implementation model.

Conclusions

The article set out to provide insights from 121 bilingual teachers in Bogota, Colombia, regarding CLIL implementation in ten participating private schools. The results all point out that the content and language-integrated learning (CLIL) approach is still unfamiliar to teachers in the private Colombian educational sector. Data also brought to light the fact that some private schools continue to follow European educational standards that are often not in sync with the Colombian educational context, thereby complicating the successful integration of content and language. The results from this study also coincide with other research in the field (Banegas, 2012, 2020; Pérez Cañado, 2016a; Puerto & Rojas, 2017; Torres-Rincon & Cuesta-Medina, 2019). Specifically, in understanding that to succeed in CLIL implementation, it is vital to re-train teachers on different teaching methods as well as different ways of working with content-specific language in a CLIL environment while helping them to understand the benefits of teachers working cooperatively (McDougald, 2015).

As noted above, CLIL implementation can improve language and content standards and promote the program training focused on the appropriate way to teach content areas (Rodríguez Bonces, 2011). Consequently, the implementation of the CLIL approach in Colombia requires further research that orients teachers on the correct methodologies or approaches of content and language applied in learning processes, following standards and criteria that correspond to the needs of the Colombian context.

Furthermore, the literature has been persistent in stating that to qualify teachers for CLIL implementation in Colombia, it is necessary to use CLIL not only as a pedagogical model but also as a path for researchers to identify how content and language are best learned and taught in integration (Lasagabaster and Sierra, 2009a). Considering this, before undertaking the implementation of CLIL, it is crucial to gather information on teachers’ perceptions of CLIL (McDougald, 2016). The information collected from the questionnaires and interviews implemented in this study could be used as support for CLIL implementation in the 10 schools that participated. Similarly, in other studies focused on Colombian educational context (Corrales et al., 2016; Curtis, 2012b; McDougald & Pissarello, 2020; Rodríguez Bonces, 2011; Torres-Rincon & Cuesta-Medina, 2019) researchers propose a number of actions to be taken such as teacher training, material development, cultural and intercultural competence, and language and content competence.

Additionally, during the structured interviews, participants agreed about the lack of representation of teachers voices in the processes of implementing CLIL in their schools, which can affect its effective usage in those institutions. When teachers’ views are neglected, few or no new ideas are conceived. Research shows that when teachers are engaged in school decisions and collaborate with administrators and each other, the school climate improves (Richard and Halley, 2014). Teachers disclosed their concerns bearing in mind how the school board perceives their role, not as active participants that can make decisions but solely as workforce, which is similar in nature to their voices not being heard as part of the implementation process. Nevertheless, CLIL is conceived as a collaborative approach, thus, it might be expected that school boards and teachers work as a network to engender a symbiotic educational relationship, in which each side nurtures the other when designing, implementing, and adjusting the curriculum. Nevertheless, using CLIL in education to balance both content and language, is still a novel teaching approach in Colombia. Hence, bilingual teachers and self-contained teachers are unacquainted with the implications of teaching using a CLIL-oriented approach in the Colombian context.

Once the teachers and school boards have reached a stage where they work collaboratively and participate in the implementation process, it is advisable to strengthen the relationship among teachers. This relationship fosters teamwork in various functions, including co-planning a scheme of work, co-planning lessons, co-constructing materials, co-assessing performance, co-evaluating the implementation process as a whole, and, last but not least, working collectively on global goals for their institutions on how to integrate language and content.

Moreover, by considering these actions, teachers’ needs and misconceptions about the approach can be better addressed, leading to improved teacher practices that effectively apply CLIL principles and competencies (Murillo-Caicedo, 2016). Consequently, it becomes possible to successfully implement processes for learning specific content using a foreign language as the medium of instruction.

One of the main findings of this study emphasizes the importance of developing a robust curriculum that effectively balances language and content to achieve CLIL principles. Similar findings were highlighted by Mariño (2014), aligning with the outcomes of this study, which emphasized the need for teachers to reach a consensus on the use of CLIL before integrating it into their teaching practices. Both studies underscore the significance of meaningful and context-oriented teacher training, as well as planning that enhances teachers’ awareness of the theoretical and practical aspects of CLIL.