Introduction

In general, authentic materials refer to a broad range of audio-visual and written resources that are frequently designed by and for native speakers of a language. These materials fulfil a communicative purpose within the context of a native language community and were not initially intended for pedagogical use. While the incorporation of authentic materials in language teaching is not a recent practice, there is a growing emphasis on providing learners with meaningful language learning experiences in the classroom. Moreover, language teachers are increasingly drawn to use such materials as substitutes for textbook materials due to their easy availability online. This trend has been further reinforced by the emergence of new technologies, as well as the challenges posed by COVID-19 pandemic and post-pandemic times. Yet, the use of authentic materials remains primarily limited to a select group of scholars rather than being a widespread practice among practitioners. Similarly, there is a need to prepare pre-service and in-service teachers to develop appropriate tasks and activities utilizing these resources. Therefore, the purpose of this article is two-fold: first, to provide a comprehensive overview of the use of authentic materials, and second, to guide teachers in systematically using these resources through the different phases of a task design, with a specific focus on enhancing listening comprehension.

Consequently, the first part of this article accounts for a review of research on the subject that contextualizes our work both globally and in Colombia. Through this review, we have identified the benefits and challenges of using authentic materials for developing various language skills, and specifically, for listening comprehension. Furthermore, we have noticed a scarcity of guidance on how to design activities that effectively exploit these materials. As a result, the second part of the article offers a set of guidelines intended to assist practitioners in creating activities that enhance listening comprehension using authentic resources such as videos.

Authentic Materials and Task Design

Research conducted on the use of authentic materials and their impact on developing students’ communicative competences shows the positive results of this pedagogical approach. For instance, Gilmore (2011) conducted a study to explore the effects of employing authentic resources as opposed to textbook materials to the develop linguistic, pragma-linguistic, socio-pragmatic, strategic, and discourse competencies of Japanese learners. The findings suggested that the use of authentic materials and related tasks was more effective in fostering a broader range of communicative competencies in learners than textbook materials. This is because the richer input provided in authentic materials, as well as helping learners notice useful language features through careful task design and follow-up practice activities, favor most components of the communicative competence model. Thus, effective tasks need to be carefully designed to meet learners’ communicative needs and interests by providing them with opportunities to practice the target language and get familiar with its discursive features. Moreover, developing teachers’ expertise to exploit these kinds of materials is crucial to achieve learning goals.

In a similar vein, Segueni (2016) conducted a study on the effects of using authentic materials to develop the communicative and pragmatic competences of learners. The results indicated that tasks that incorporated authentic materials contributed positively to this development and were interesting to students. A significant contribution of this study was demonstrating that these materials helped increase learners’ confidence when using a foreign language. According to Segueni (2016), learners’ self-confidence and independence are boosted when they use English in real-life situations where they may hesitate, hear unclear utterances, participate in turn-taking, and encounter other linguistic features that help them become proficient users of the target language. Segueni also suggested that language functions, grammar, prosody, and lexicon are better acquired when learners are exposed to a wide array of authentic materials with clear communicative goals. This implies that task design should be based on a set of communicative objectives, and emphasis should be placed on different components of the communicative approach to language teaching.

Castillo et al. (2017), in turn, analyzed the impact of authentic materials and related tasks on the communicative skills of Colombian university students at an A2 level. The study found that using these resources improve students’ communicative competence and English teachers’ classroom practices. Nevertheless, the authors note that a successful implementation in foreign language learning contexts depends greatly on the teacher’s experience with these materials and the pedagogical support offered to learners during their use. As a result, it is necessary to introduce these materials in the classroom following a well-planned and structured framework to avoid their isolated use. Moreover, effective transitions between the pre-activity, the actual activity, and the post activity need to be carefully planned to ensure that the materials are used appropriately and that learners receive the necessary pedagogical support.

The benefits of authentic materials for fostering listening skills, vocabulary learning, and reading comprehension have been studied extensively. Ghaderpanahi (2012) in his study on how the listening skills of EFL students were shaped by authentic aural materials found that learners who were exposed to authentic audio recordings of native speakers showed significant improvements in their listening comprehension. Throughout the lessons, the students listened to authentic texts and engaged in pre-listening exercises, such as discussions about illustrations, pronunciation, and matching definitions with vocabulary items. During the first listening, the teacher paused the aural text after a few sentences and asked students to identify the vocabulary items they had practiced during the pre-listening phase. The students then listened to the text several more times and were asked to take notes and identify the main idea and supporting details. Additional tasks included answering questions and identifying specific information they later discussed with their classmates.

In addition, Kraiova and Tsybaniuk (2015) investigated the impact of authentic videos on the listening proficiency of students in a foreign language program and sought to improve the effectiveness of lessons incorporating such videos. The implementation of these video materials improved students’ motivation as they took part in real communication exchanges, exposing them to a natural use of the oral language and providing access to authentic cultural information. The authors recommended some steps to prepare for a lesson that incorporates these materials. For instance, they suggest a pre-watching task where students get prepare for the situation featured in the video by studying new vocabulary and the necessary grammar to complete a given communicative task. During the lesson, students may engage with tasks that focused on vocabulary and specific types of listening skills, such as identifying the main idea, details, a sequence, attitude and opinions of the speakers, and functional language. Additionally, they sustain that materials can be exploited widely during the watching stage when teachers consider the specific needs of their students. Although Kraiova and Tsybaniuk provided a comprehensive description of each of the possibilities during the while-listening stage, they did elaborate on tasks suitable for the post-listening stage.

Regarding vocabulary, Ghanbari et al., (2015) conducted a study on the effectiveness of using authentic materials for vocabulary learning. The study involved two groups of students, one of whom used online newspaper as authentic material for vocabulary practice while the other group relied solely on their English textbook. The researchers read the authentic online newspaper with the students, discussed its topics, and explained unfamiliar or difficult words. The study found that the group that used the authentic material showed a greater increase in vocabulary knowledge than the group that only used their textbook

On the other hand, Maxim (2002) researched the impact of authentic materials on reading comprehension, specifically analyzing the effects of extensive reading on language proficiency. The study found that beginner-level learners of German were able to successfully read a long unedited novel. It also shed light on the key procedures that could help ensure students’ comprehension. A systematic approach was used to guide learners through the novel, which involved tasks such as identifying, summarizing, and analyzing information. Group reading provided learners with opportunities to work together towards achieving understanding, share background knowledge, and practice reading strategies. The combination of careful task design and group interaction was found to be crucial for successfully approaching this authentic reading material.

The studies previously mentioned provide evidence that authentic materials are valuable assets in language classrooms. In addition to aiding in the development of various linguistic elements, authentic materials increase students’ motivation, confidence when dealing with real-life language, concentration, and engagement in activities. Likewise, these materials are useful to develop intercultural competence (Gómez, 2012; Bernal-Pinzón, 2020), provide examples of authentic language use by native speakers, and facilitate connections between classroom activities and real-world situations. Language employed in authentic materials is also considered to be pedagogically appropriate, interesting, and motivating, especially for advanced learners (Mishan, 2004, as cited in Liu, 2016).

Some Caveats about Using Authentic Materials

While many studies tend to highlight the benefits of using authentic materials, several challenges come with their implementation, as noted in previous research (Alfonso & Romero, 2019). Firstly, searching for appropriate materials and creating suitable complementary tasks can be daunting for teachers (Zyzik & Polio, 2017). Using a resource whose language notably exceeds the learners’ level might cause frustration and demotivation (Al-Azri & Al-Rashdi, 2014). Poorly designed task or activities can also hinder learning outcomes. Other concerns researchers have identified include the potential for authentic materials to quickly become outdated, which requires teachers to invest more time in finding new samples and preparing activities (Torregrosa & Sánchez-Reyes, 2011). In some cases, the use of authentic materials may favor some skills over others. For example, Borucinsky and Jelčić-Čolakova (2020) reported that authentic materials may not be suitable for teaching reading comprehension and grammar, and recommended incorporating a mix of authentic and non-authentic resources. Furthermore, cultural aspects in authentic materials may pose additional challenges to teachers, who may need to spend considerable time explaining contextual features (Blagojević, 2013, as cited in Borucinsky & Jelčić-Čolakova, 2020).

Efforts should be made to move beyond the graded language in textbooks and provide learners with a real-world understanding of English, exposing them to a variety of accents, vocabulary, pace, and register, as well as other sociolinguistic features. This exposure will nurture learners’ overall independence and confidence. Although the classroom is a safe environment for learning, educators must keep in mind that students will eventually need to use English outside the classroom (D. Weller, personal communication, January 27, 2021). Therefore, teachers need to be equipped with the ability to exploit authentic materials by designing tasks and activities that systematically guide students in their learning process. Following a pre-, while-, and post-stage cycle of activities can be a useful approach. This should be promoted as a widespread practice for all of teachers, rather than just a few isolated successful endeavors of researchers.

Authentic Materials and Listening Comprehension

Numerous studies have shown that teacher-researchers commonly utilize audio or audiovisual material to improve learners’ listening skills, as its benefits have been proven in various educational settings. The majority of the studies reviewed in this section indicate that these skills can be further developed when the materials are combined with pre-, while-, and post-stages (Abdulrahman, 2018; Córdoba-Zúñiga & Rangel-Gutiérrez, 2018; Kim, 2015; Raza, 2016; Reina-Arévalo, 2010; Win & Maung, 2019).

Similarly, extensive research has been conducted on teaching listening skills in the Colombian context. What follows is a selection of studies that provide insights into the main points we wish to illustrate in this article. These studies have been conducted with a variety of participants and teaching contexts, especially high-school students (Mayora-Pernia et al., 2019; Zuluaga-Franco, 2020) and non-English major undergraduate students (Bermúdez-Puello, 2017; Gavilán-Galindo & Romero-Valencia, 2015) using audio or video materials. Notably, many of these studies implemented metacognitive strategies to improve listening comprehension, such as planning, monitoring, and evaluating (Bermúdez-Puello, 2017; Quijano-Plata, 2016). Furthermore, following a pre-, while-, and post-listening stage cycle has been a common practice in these studies, and some even incorporated a task-based cycle: pre-task, during the task, and post-task work (Zuluaga-Franco, 2020; Zuluaga-Franco, 2020). These studies have often utilized action research as the preferred methodology and reported positive outcomes, indicating that this type of approach has been beneficial for learners.

Over the past few decades, there has been an increasing interest in combining the use of authentic materials with pre-, while-, and post-stages to enhance listening comprehension. Pedagogical interventions where this approach is taken have been carried out by novice and experienced researchers alike (Camacho-Castellanos & González-Carreño, 2019; Naranjo-Paniagua, 2018; Zárate-Reyes, 2017; Chawes-Enciso, 2018; Franco-Vidal, 2014; Hernández-Ocampo & Vargas, 2013; Morales & Beltrán, 2006). Researchers have designed a research methodology, along with pedagogical interventions, to systematically collect evidence of the effectiveness of using authentic materials to help listening comprehension.

For instance, Morales and Beltrán delved into the use of authentic materials to enhance listening comprehension, focusing on a listening activity that was guided by Morley’s principles and Dumitrescus’ theories about authentic materials.1 Even though the paper does not explicitly underscore pre-, while-, and post-activities, these are embedded in the sequence of the principles proposed (Morales & Beltrán, 2006).

Moreover, two undergraduate theses provide further insight into the use of authentic materials to enhance listening comprehension. The first thesis described a task-based learning approach that incorporated authentic videos to improve listening skills among fourth graders in a public school (Zárate-Reyes, 2017). The second thesis emphasized the concept of situated listening and guided fifth graders to reflect on values such as emotions, gratitude, family, and friends, placing emphasis on the post-listening stage (Camacho-Castellanos & González-Carreño, 2019). Although the latter study did not focus on pre-, while-, and post-stages, they were included as part of the activities, exemplifying an accurate connection between videos, English acquisition, and students’ lives (Camacho-Castellanos & González-Carreño, 2019).

Another noteworthy study is Franco Vidal’s (2014) master’s thesis on authentic materials and listening comprehension. The pedagogical intervention involved using authentic materials in the form of videos to enhance listening comprehension of university students who required English for Academic Purposes (EAP), alongside self-assessment artifacts. Even though the main emphasis of the study was not on the pre-, while-, and post-stages of listening, the listening practice was embedded within a task-based learning approach.

To sum up, combining authentic materials and listening comprehension activities framed within a pre-, while-, and post-stage cycle has proven to be highly effective. However, despite the success of this approach, it has not been widely recognized as a pedagogical strategy, nor did the studies reported focus on instructing teachers on how to create activities to complement authentic materials. Instead, the activities were tailored only for the purposes of each specific study. As a result, it is still necessary to fill in this gap in previous studies by preparing a bigger audience of teachers to design tasks and use authentic materials in a strategic way so that a wider audience of teachers and learners can receive the benefits. Thus, this paper aims to promote the use of authentic materials and task-design as a pedagogical strategy that extends beyond individual efforts.

The Teaching Amalgam

Designing pre-, while-, and post tasks goes beyond setting up activities that fit the purpose of each stage. Finding a balance between challenge and support are key to help learners carry out a successful task. Learners face challenges when they are required to self-evaluate their work, solve open-ended tasks that do not have a single answer, analyze language structures before receiving a complete explanation, and apply what they have learned to situations such as role plays and writing exercises. On the other hand, support is provided through clear instructions, task modeling, collaborative tasks, a non-competitive learning environment that fosters confidence, and treating mistakes as learning opportunities (Mariani, 1997, as cited in Hammond & Gibbons, 2005). Scaffolding is the term used to describe the balance between support and challenge, which can be represented in a framework that combines these two dimensions to show the four basic types of challenge/support patterns teachers actually use. Low challenge and low support can result in boredom, while low challenge and high support may lead to minimal learning. Conversely, low support and high challenge can cause frustration. The most effective approach is to provide high levels of both challenge and support, as this leads to substantial learning.

This framework suggests that teachers need to provide high challenge and high support when developing tasks around authentic materials to avoid frustration and boredom in learners. Designing activities that are well intentioned but lacking in higher learning benefits is not effective. For instance, an experienced EFL teacher developed a lesson based on an authentic video about two Syrian refugee children living in Australia. Even though the activities seemed engaging, they were not scaffolded in a way that learners could be prepared and guided to engage with the content and the language in the video. This aligns with the views of several authors who emphasize that task design, not material selection, is crucial (Nunan, 1989, as cited in Gilmore 2007; Kraiova & Tsybaniuk, 2015; Zyzik & Polio, 2017). Effective usage of authentic materials requires a balance between the challenge and support dynamics in the pre-, while- and post-stages, which will be explained in the next section.

Designing Tasks for Authentic Materials

Pre-Stage: Preparing, Sparking, Exploring

Pre-stages are generally designed to captivate learners’ attention and to prepare them to face the subsequent content. According to Gilmores, in this stage tasks “are typically designed to raise learners’ interest in topics, clarify difficult vocabulary and provide any necessary cultural background knowledge to facilitate comprehension” (Gilmore, 2007, p. 6). When a top-down approach is adopted to understand the meaning of a material from its context is crucial to tap into students’ background knowledge or schemata. This way it can be ensured that a connection is facilitated between the new information and students’ prior knowledge. By activating students’ cultural or linguistic background knowledge, information is retrieved from permanent memory to the surface where it is ready to be applied, stimulated, and used to construct meaning and build interest in the targeted language.

Educators must be mindful of the differences in students’ background knowledge as they usually come from diverse linguistic, cultural, and economic settings. When teachers notice that students are struggling with the content, they “need to consider that the problem may be related to background knowledge rather than to intellectual ability” (Echevarria, et al., 2004, as cited in Wessels, 2012). Without the necessary background knowledge, students will continue to face challenges in comprehending the material. Therefore, when the content appears to be unknown, building cultural background is necessary to facilitate comprehension, as noted by Zyzik and Polio (2017) , “instructors will have to ensure that they devote a fair amount of time to providing students with the cultural knowledge that they do not have” (p. 72). To build students’ background knowledge, various strategies can be employed within the given context of communication, such as visuals, discussions, read-alouds, graphic organizers, hands-on activities, questioning, and narratives.

Furthermore, in a top-down approach several general procedures such as raising the learner’s interest in the topic are advisable. For example, the instructor may connect the material to their context, tap into students’ schemata or provide any necessary cultural background knowledge to facilitate comprehension. Other examples of procedures are predicting the content of the material based on given vocabulary words or chunks of language, putting a series of pictures or sequence of events in order, listening to conversations and identifying where they take place, reading information about a topic then listening to find whether or not the same points are mentioned, or inferring the relationships between the people involved.

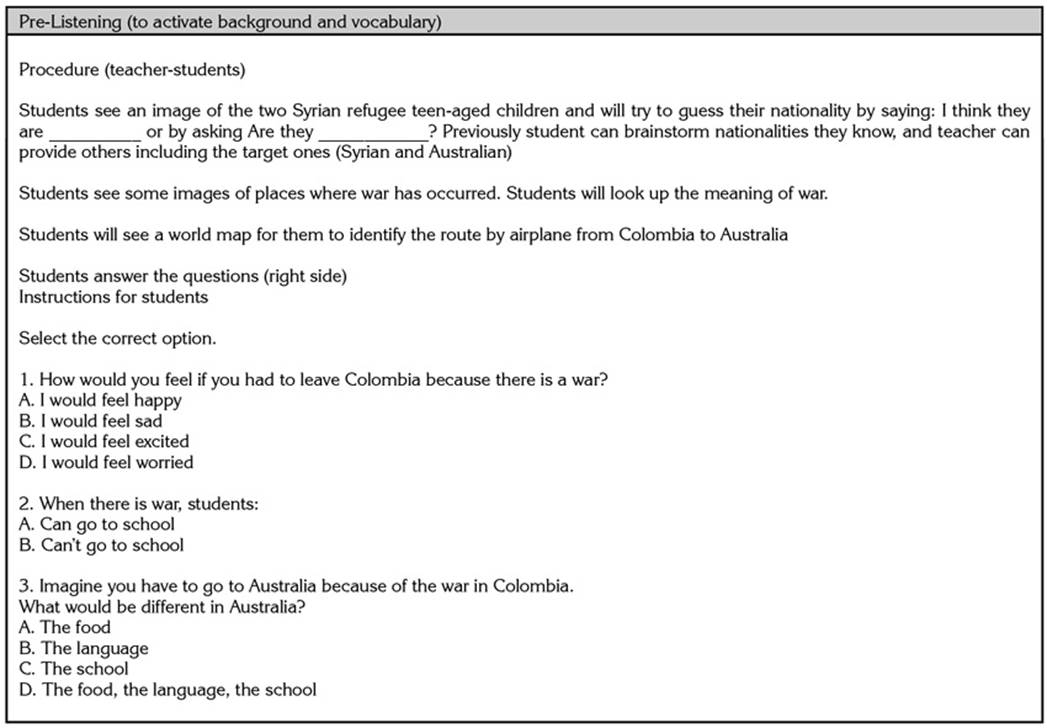

To provide an example, let us refer to the video about the Syrian refugee children mentioned earlier. Table 1 presents a possible pre-listening stage we designed to help students at a higher beginner level walk through the content of this authentic video material.

In this example, it can be noted that the pre-listening phase of this lesson focuses on meaning mostly by tapping into teen-aged learners’ background knowledge about nationalities and feelings. Support to activate or build background knowledge is provided by showing a world map where students can see the route from Colombia to Australia. Likewise, the use of images provides comprehensible input and spark students’ interest in knowing about students from another place in the world. Additionally, teachers can provide a challenge by asking learners to express their emotions about leaving their country, with the help of multiple-choice options that serve as linguistic support.

Meanwhile, in a focus on form (bottom up) approach, learners use their knowledge of the language to comprehend content as they are guided to pay attention to the smallest elements of language (sounds, words, intonation, grammatical structures) and put them together to construct meaning. Preparing students for unknown vocabulary, pronunciation, or grammar is characteristic of some examples of pre-stage procedures that focus on bottom-up processing skills for listening and reading activities designed with authentic materials. Research on listening instruction suggests that pre-teaching vocabulary might not be helpful as “students do not have time to access the new word knowledge” (Chang & Read, 2006, as cited in Zyzik & Polio, 2017, p. 75). This means that involvement or engagement with words is needed for retention, either for authentic or non-authentic materials.

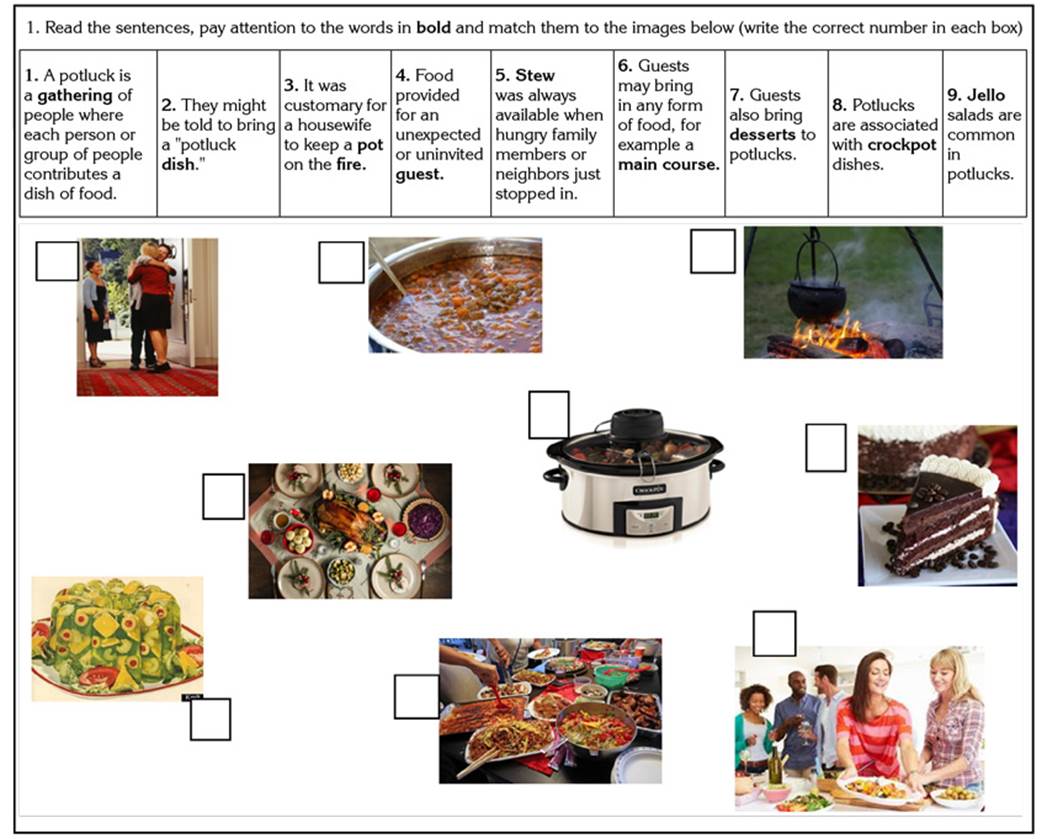

To encourage retention and comprehension, pre-listening or pre-reading stages should go beyond providing definitions or translations of a list of words. It is necessary to encourage students to search for the meaning of the word or evaluate if they are using it correctly in context before going into the actual listening or reading material. For example, when preparing intermediate level students for reading an authentic text about the origin of potlucks in the U.S., the following focus-on-form activity presented on Table 2 might be useful.

In this pre-reading task, learners are challenged to read fragments taken from the actual reading material, identify the target vocabulary words in context, and find the matching image. This task encourages learners to engage in close reading, observation, analysis, and other activities that are likely to promote retention. However, since potlucks are a very usual practice within United States communities and culture that many Colombian learners may be unfamiliar with, the teacher’s first job is to provide support (build background) before asking students to focus on vocabulary, even when it is presented in context. One way to do it is by showing some images of potlucks and elicit ideas about the event, such as people, food, sharing, etc., or surfing the web to find its meaning and related images.

To help students at an advanced level with grammar structures they will encounter in a text, teachers can focus on these structures in context. For example, teachers can provide sentences with difficult verb forms, but with the verbs deleted. Students then can work in pairs or individually to fill in the missing verbs, followed by a whole class discussion (Zyzik & Polio, 2017). This can be complemented during the while-stage.

While-Stage: Establishing a Purpose

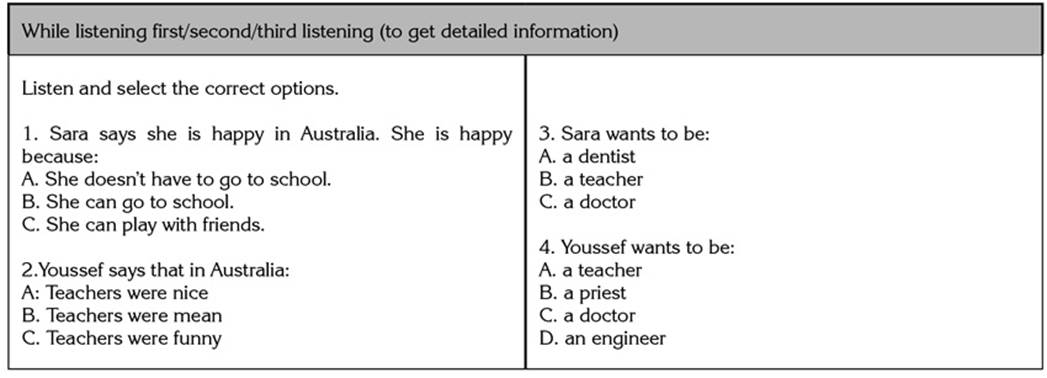

For the while-stage, learners need to be aware of the purpose for listening or reading. In other words, listeners or readers should know in advance what they are expected to do when engaging with the material, which could be either focusing on meaning or focusing on form. According to Gilmore (2009), “while-listening tasks focus on meaning first, before shifting to form, to avoid overloading learners’ language processing systems. While-listening tasks typically begin with gist questions, followed by more detailed comprehension questions to encourage effective processing strategies” (p. 6). Table 3 shows the while-listening phase proposed for the video about the Syrian refugee teenagers explained previously.

During the while-listening phase, learners are encouraged to actively listen for specific information about the new school life of the Syrian children in Australia and the professions they wish to pursue. The multiple-choice exercise does not load students cognitively as language is kept short and simple, yet meaningful to ensure understanding (support).

Alternatively, to focus on form at the advanced levels, Polio (2014) suggests choosing a text and creating a reading or listening cloze by deleting, for example, prepositions or articles. This type of activity has multiple benefits, including drawing students’ attention to a structure that they may miss when reading for the main idea and requiring them to read or listen closely to the entire text in order to decide on the correct structure.

When working with vocabulary at the beginning level, there are several tasks that can be completed with minimal language skills. For example, listening for the sequence in which a list of items is named by the speaker and writing down the corresponding ordinal number in front of the appropriate vocabulary item. A variation with the same material would be listening to a video and circling the vocabulary or chunks of language that are mentioned. Another approach to using authentic materials with beginners is to assign students to explore prices of given items in different clothing stores online and having them compare prices with their classmates (Polio, 2014). To do this, students can fill out a table with two columns where they write down prices of the clothing items. Then, they can use a grammatical structure such as “item A is cheaper than item B, or item C is more expensive than item B” to write complete sentences that they can share and analyze as a class.

It is clear that “working with authentic videos is not that different from working with non-authentic ones as using both resources involve pre-, while-, and post watching stages” (Alfonso-Vargas & Romero-Molina, 2019, p. 33). Nonetheless, we underscore that there are two crucial elements to help learners succeed when engaging with authentic materials. First, teachers’ understanding of the extent of challenge and support students need while navigating the pre-, while- and post-stages. Support clearly connects to the idea of providing scaffolding, something temporary to be gradually removed as the structure being built becomes stronger and more reliable (Mariani, 1997, as cited in Hammond & Gibbons, 2005). Thus, a rigorous scaffolding process needs to be carried out to maximize students’ learning gains. Second, it is crucial to propose follow-up tasks as they are essential at the post-watching stage.

Post-stage: Revising and Squeezing the Material

Teachers are concerned about how time-consuming it could be finding appropriate materials and designing activities oftentimes. Moreover, they often fail to exploit these resources thoroughly, resulting in wasted time and effort. In Gilmore’s words: “Texts are often abandoned too quickly by teachers when the potential exists to ‘squeeze’ much more out of them, and valuable time is lost when we have to constantly set up or contextualize new input” (Gilmore, 2007, p. 7). The post-stage is an invaluable opportunity for the teacher to expand on language practice by helping learners connect new knowledge (e.g., grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, idiomatic expressions) obtained from the authentic material to their real life through written or oral post activities. In this regard, Gilmore (2007) suggests that “post-reading or post-listening tasks are designed to ‘revisit’ the material in a new way. This can involve a wide variety of tasks, such as recycling vocabulary, focusing on target discourse features, or getting students to use (the) target language in speaking or writing activities” (p. 7). Thus, this stage implies involvement or intentional and deep work on target items.

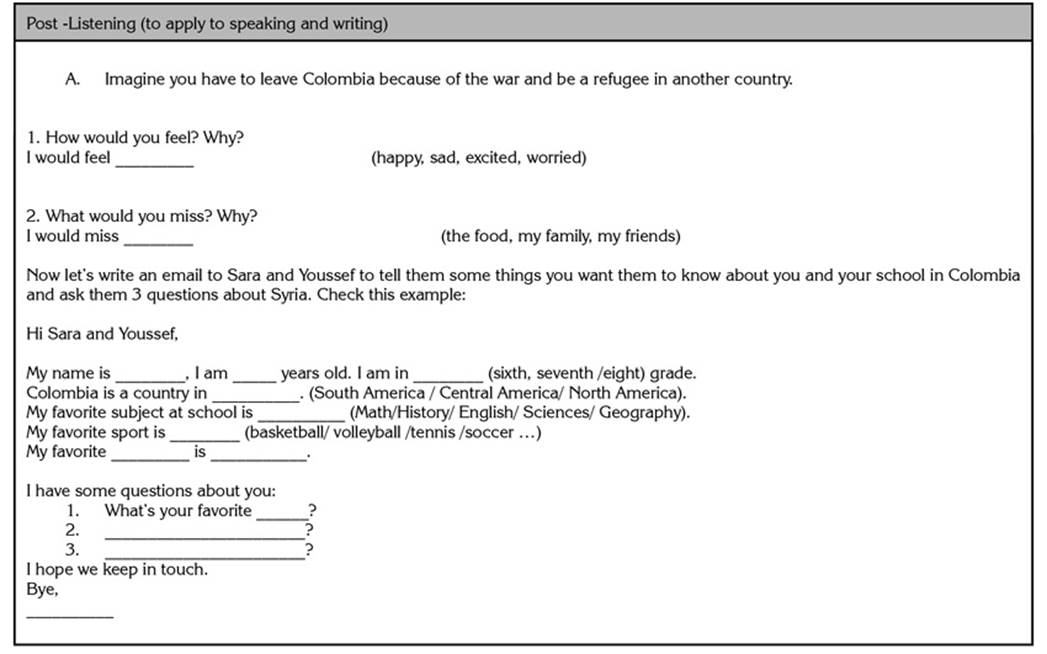

Laufer and Hulstijn (2001) suggest that three factors, need, search and evaluation, are necessary to help retention of new language. In the post-stage, teachers need to move beyond having students answer comprehension or reflection questions, they need to create tasks that demand high involvement. For example, by encouraging the creation of new products or projects that include making brochures, writing stories, doing surveys, making videos or other real-life tasks and artifacts, learners are encouraged to integrate and use new language items. During this process, “learners are required to go back to the language worked on at the pre- and while-stages (i.e., need); find the language they need including aspects such as pronunciation, meaning, part of speech, grammar, etc. (i.e., search); and analyze (i.e., evaluation) how to integrate it within the given products” (Alfonso-Vargas & Romero-Molina, 2019, p. 32). However, these activities must not only stretch the linguistic abilities of the students but create meaningful connections to their own culture/context. Table 4 presents a proposal for a post-listening stage activity on the same material about Syrian children refugees.

Table 4 shows that this task challenges learners to reflect and express how they would feel if they were in the refugee children’s shoes by asking them to write an email to introduce themselves and give a short description of some of their interests. On the other hand, support is provided by showing a model and some prompts and by encouraging and reassuring students about their potential and ability to develop this kind of task. This process enhances student’s involvement (i.e., need, search and evaluation) with the language

Conclusion

Nowadays, it is increasingly important to equip learners with the skills they need to communicate effectively in English in real-world situations, whether in face-to-face encounters or online interactions, which in pandemic and post-pandemic times are more prevalent. Hence, the possibility of accessing the Internet and finding endless sources of authentic digital materials represent a great opportunity for educators to continue challenging and motivating their students in EFL classrooms.

This article has shown that while some teachers use authentic materials, they are not widely used resources. Studies pointed at a need for more guidance on how to design tasks and activities to exploit them adequately. Additionally, task design around a pre-, while-, and post-stage is central when working with authentic materials. However, following this structure alone might not be enough for learners to really access language knowledge. It is crucial for teachers to understand the extent of challenge and support students need when completing a task. Therefore, the success of tasks designed around any authentic material relies mainly on the scaffolding process planned by the teacher.

One potential limitation of using the amalgam model described is accessing digital authentic materials, especially the audiovisual resources, as not all places have reliable Internet connection. In such cases, we would encourage finding resources which could be downloaded beforehand from authentic sources. Additionally, teachers could design activity worksheets based on the resource content, and, if possible, make copies for students to share.

Furthermore, finding a suitable balance between challenge and support may require some experimentation and adjustment. So, teachers should not be discouraged by this. We recommend experimenting with activities for the pre-, while- and post-stages. Then, documenting the results, (e.g., by briefly making some sketch notes of students’ outcomes and reactions towards the activities proposed after completing the stages of the cycle) might help analyze the effectiveness of the tasks and activities set. This analysis, in turn, will facilitate making adjustments in support and challenge for future activities as needed

While it is widely recognized that using authentic materials in language classrooms can be challenging, it is also important to acknowledge their strong potential in promoting learners’ language development and motivation. Thus, teachers are encouraged to trust the advantages of using such materials systematically, overcome pedagogical obstacles, and engage themselves and their students in meaningful language learning experiences. Furthermore, documenting experiences in various settings may be accounted in a methodical way to enrich the research on the current use of authentic materials, particularly in the digital format