Introduction

“La forma *«semos» por «somos» es un vulgarismo que ha de evitarse en el habla culta” (RAE, 2018)

Regional literature is not readily found in Latin American literature anthologies despite its immense historical, cultural, and linguistic richness. The vivid language used to depict the geographical background both situates the narration and contrasts with the language of the dialogues. Arguably, the most salient feature of the text is its dialogues, which effectively capture the elisions, aspirations, clippings, and contractions that characterize rural dialects. This characteristic serves to distinguish regional literature from other genres.

Cuentos de Barro (1933), written by Salvadoran author Salvador Salazar Arrué’s (known by his pseudonym Salarrué), is a collection of short stories that illustrate the poverty and violence inherent in the literary representation of the peasant.1 In each of the stories, peasant speech is highlighted by the use of eye dialect (dialecto literario). As noted by Martha Mendoza (2017), Salarrué's collection portrays a literary Salvadoran peasant through its narration and dialogue. More importantly, as I sustain throughout this research, Salarrué’s use of dialecto literario shapes this identity and offers significant dialectical variations and opportunities for language learners, especially heritage learners, to engage with the text despite the challenges it poses in comprehending it.

In this research study, access to the background knowledge of three separate groups of students was probed for its ability to decode the words written in non-normative orthography from “Semos malos”, one of the stories from the Cuentos de barro collection. The selected isolated words were distributed among three groups, each comprising six students, to assess their ability to understand the meanings in isolation. Subsequently, following their exposure to the short story, these groups were tasked with reinterpreting the words in the context of complete sentences. My hypothesis posits that students who orally learned Spanish might have more informed background knowledge to decode the dialecto literario and may be able to understand more easily the underlying normative orthography. While criticisms directed to literature employing dialecto literario seems to warrant its exclusion from the classroom, there exists a group of students who are potentially well-equipped for understanding such texts. Heritage students who have orally learned the language are better poised to recognize oral phenomena represented by the standard alphabet. With the added linguistic strategies of listening to speech and then exploring ways of spelling it using the normative orthography, students are able to decode the oral phenomena and understand the text.

Historical Background of Cuentos de Barro

The collection was written in 1933, around the time of the overthrow of the government by Col. Maximiliano Hernández Martínez and La Matanza de 1932 in El Salvador, “Cuentos de barro desglosaría un mundo campesino—violento, crédulo y tradicional—pero sin un vínculo directo a los preparativos de la revuelta de 1932” (Lara Martínez, n.d., p. 83). Despite the many attempts to silence and erase the 1932 Matanza from any written record, Salarrué’s collection offers a linguistic tribute and a cultural refuge for the indigenous cultures of the tens of thousands of peasants who died after revolting against the repressive government. The dialogues in the collection of stories incorporate dialecto literario, or the deliberate misspellings in literature based on popular pronunciations, which serve as a testament to the peasants that fought against the Martiniato. Moreover, this linguistic variance reflects the political globalizing forces at play during the time as Latin American literature began carving out a space in the global context by defining its regional autochthony as an exportable cultural product.

The examples of eye dialect are extensive in Salarrué’s work. While most stories in the collection do not immediately accentuate the contrasts between the various types of dialogues presented, there are exceptions, as seen in “Hasta el chaco”, where the more formal dialogues of normative orthography contrast sharply with the dialogues of eye dialect. Moreover, certain stories adopt a more narrative style, incorporating both regional vocabulary and its spoken representation.

Eye Dialect (Dialecto literario)

The literatures of Central America specifically provide a rich source of eye dialect, dialecto literario, but they remain largely unknown to Spanish students because Latin American literature classes tend to underemphasize or deemphasize the contributions of Central America to regional literature vis-à-vis other Spanish-language regional literatures within their ‘Latin American’ literary canon. In fact, Central America seems to be largely invisible in US-Latin American identity constructions. It is “often constructed through the abjection and erasure of the Central-American American” (Arias, 2007, p. 186). Indeed, in the rare moments that Central America emerges in US mainstream cultural registers, its appearances are often relegated to racialized narcos, gang members, or generic criminals, thus causing what Arias (2007) calls a double marginalization, resulting in a lack of visibility of Central American cultures. These attitudes bleed into the US “Latin American” literary canon, causing scholars to incredulously pose the question, “is there really a Central American literature?” (Arias, 2007, p. 186). Indeed, such race and class considerations are central to the study of eye dialects, as the characters who express themselves through eye dialects, are usually illiterate, poor, and/or brown (codified as indigenous/indio, campesino, mulato, prieto, etc.). With this in mind, popular definitions of eye dialects, “the use of misspellings that are based on standard pronunciations (as sez for says, and sup for what’s up) which are usually intended to suggest a speaker's illiteracy or his use of generally nonstandard pronunciations” (Merriam Webster, n.d.), do not consider this important characteristic. According to Siegel (2010), out of the three types of dialect, namely national, regional, and social, the last two categories, i.e., regional and social, are greater indexical properties of identity and are strategically highlighted in regional texts. Moreover, they carry more information than just the content of the message; they distinguish the speaker, “a speech variety serves partly for simple communication, but just as importantly to express an identity” (McWhorter, 2000, p. 45).

Alonso divides the qualities of this type of literature into three categories: oral language represented with nonstandard orthography, glossaries of regionalisms that form addenda to the text, and, finally, boldfacing, italicizing, or enclosure of text within quotation marks to identify the autochthonous identities of the protagonists. More importantly for this research, however, these features of costumbrismo2 reflect the globalizing political forces at play during the period in which Latin American literature began carving out a space in the global context through the definition of regional autochthony as an exportable cultural product. Unfortunately, collections of short stories like these, specifically a subset of regional literature, novelas de la tierra, have been criticized by Latin American scholars for literary immaturity, excessiveness, and primitiveness, as they stand in stark contrast to the elite literature de la ciudad, which tend to follow more “formal” (European) traditions of creating literature (Alonso, 2008, p. 74).

Thus, like other countries in Central America, the regional literatures of El Salvador have an important critical place in the Latin American literary canon as taught in the US.3 However, these texts add another layer of complexity to the already unfamiliar regional vocabulary present in these texts which is not represented in the traditional canon. The typical native speaker (L1) reader will have one hurdle to overcome while reading these texts: a second dialect (D2) of an already familiar language. Critics of regional literatures often cite the clumsiness of accompanying glossaries of regionalisms; these are a necessity for readers who are not familiar with the variety of Spanish spoken in that region in large part because many of these lexical entries are not found in either bilingual or monolingual dictionaries. The unfamiliar vocabulary in addition to the nonstandard orthography of familiar vocabulary results in a challenging text for the native and heritage Spanish speaker alike. Indeed, many students cannot even proceed beyond Salarrué’s title, “Semos malos”. What is “semos”? Is it a plural noun? Is it a plural verb? Is it perhaps a typo? Unsurprisingly, included at the beginning of this paper is a tweet (tuit) from the Real Academia Española that responds to a query about whether to use “semos” or “somos”. The RAE prescriptively informs that “semos” is “vulgar” and should be avoided.

Eye Dialect and the Heritage Learner

Languages and their nonstandard dialects are always at the center of every language curriculum. The transition from oral language to its written form is a task that many speakers of a language struggle with, especially heritage learners who have only acquired oral Spanish proficiency. Many heritage learners in the United States have Spanish as their first language, but, when they begin school, their formal education is given in English, not Spanish. As a result, they may have never seen the written form of the words that they are using for their communication. Consequently, it would be easy to confuse letters that sound the same. For example, the distinction between “b, v” or “s, c, z” and the presence/absence of “h” in writing. Students feel that their heritage language abilities are inferior to those of their “native speaker” peers and often suffer from low self-esteem as a result. In addition to the Real Academia Española (RAE), the Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Española (ANLE) in their series “¡Dígalo bien!” and their publications: “Hablando bien se entiende la gente”, now in three separate volumes, inform what is “correct”, thus, lead the speaker who opts for “aplicación” instead of “solicitud” or “postulación” to believe that they are “incorrect”. Afterall, if the message (in the imperative) is “¡Dígalo bien!” then, the only logical conclusion is “lo dicen mal”. In their tweets (tuits) and formal publications, neither institution seems to embrace or tolerate language contact phenomena: calques, semantic extensions, or lexical borrowings. Sadly, many heritage speakers often comment about how they wish that they spoke the language “correctly” because their variety is not desirable.

While there is still debate regarding the relative difficulty of acquiring a second language (L2) versus a second dialect (D2). Wolfram & Schilling-Estes (1998), among many other linguists, believe that the acquisition of a second dialect can be more challenging than the acquisition of another language especially if the learner does not perceive the differences between the two. Their stance can be bolstered by Flege’s Equivalence Classification (1986) which states that for any given feature, the more alike two languages/dialects are, the less likely one is to notice a difference. For example, the “t” and “d” in Spanish are dental stops, but they are alveolar stops in English. The identical spelling and slight variation in pronunciation oftentimes goes undetected (unnoticed) by the English speaker learning Spanish, who then never acquires that dental place of articulation and will never “sound” native as a result. On the other hand, the “rr” and “r” distinction is easily detectable, audible. Non-native speakers of Spanish “hear” (notice) the difference between the trill (in initial word position, for example) and the tap, even if they are incapable of producing the distinction in their own pronunciation.

Salarrué’s collection of stories Cuentos de barro contains all of Alonso’s criteria (2008) for regional literature, encompassing both elements of Salvadoran regionalism: local vocabulary and eye dialect. Although these two features might potentially complicate the reading process for students, scholars have proposed ways to integrate Central American regionalisms into the classroom, making them accessible and relevant. These texts have been overlooked for too long because of their style and linguistic complexity. In what follows, I argue for the necessity of the incorporation of regional literatures in the curriculum for two compelling reasons: (1) to foster positive self-esteem in heritage language learners through usage of their own oral knowledge to read/decipher “oral” text, since many heritage language speakers have the impression that they speak an inferior form of the Spanish language which impacts their self-esteem and makes them reticent to participate in class and to excel; and (2) to foster appreciation of underrepresented texts, specifically from Central America, for their historical and cultural richness. These texts transcribe in a non-linguistic format the speech patterns, their context, and the variability that cannot be “seen” orally. Speech dialects are rule-governed, encompassing phenomena such as aspiration, glottalization, elision, and reinforcement, among others. Regional literature provides a clearer lens through which to identify these phenomena. The students have access to written documentation of the speech phenomena allowing them to better process the information and compare and contrast the contexts for those variations. Language, after all, is spoken, and even the written standard form is, at best, an approximation. One of the goals of the current study is to empower the heritage language speaker students by relying on the knowledge and experience from their own speech patterns to develop the skills necessary to identify and decode the non-normative spellings. Students equipped with the necessary background knowledge will be able to read regional literature while simultaneously learning more about the dialects of the Spanish language along with their respective cultures. The discoveries made by the students should be complimented by some basic phonological tools as they complete the reading activity.

Literature in the Classroom and Schema Theory

Literature, as principal course content, in general, appears in the language students’ curricula often abruptly during the second or third year of language study. However, possessing content and formal schemata can be an advantage for anyone reading/listening to new text because they help to provide context for guessing the meaning of unknown vocabulary or concepts. Beginning with Bartlett in 1932, schema theory has evolved to explain how comprehension obtains via interaction with a text as shaped by one’s own personal, cultural lens and knowledge of the world. Heritage learners have a unique lens which may afford them better insight to decode dialecto literario text. Miscues occur, however, when a word or practice is translated from L2 to L1, but its connotation is not necessarily understood in the target cultural context. L1 cultural references are often imposed on target language (TL) text in the absence of sufficient TL proficiency and/or target culture background knowledge. Appropriate pre-reading activities can help to bridge these gaps. In an examination of varying types of pre-reading activities, it was found that without sensitivity to the target language culture, known vocabulary words did not transport the contextual/cultural meaning necessary for successful reading comprehension, but, “deficiencies in language proficiency can be fortified through adequate and appropriate cultural schemata initiation/instantiation to allow for increased reading comprehension (Cloonan Cortez, 2000, p. 196). While each culture has a framework that arranges sequences of events and frontloads certain expectations that shape the readers’ comprehension during the reading process, students of literature, however, cannot always avail themselves of this advantage. Heritage learners whose linguistic knowledge is based upon an oral acquisition are uniquely poised to use their background knowledge to decipher eye dialect text.

Affect and Anxiety

Native speakers, heritage learners, as well as L2 learners, often do not feel prepared for the traditional literary canon with their proficiency upon entering the literature classes. Whatever linguistic confidence that the language students may have acquired up to this point seems to quickly disappear when they meet the task of reading in their literature anthologies (Nance, 2010). Student emotional, or affective, responses play an important role in the desire to read literature from the traditional canon. Forms that they encounter in literature from past centuries will not be practical for current day communication. The term literature seems to make students tense because of its implicit formality. Disaffected students in language classes have negative attitudes which are exacerbated by literature that is not engaging. Moreover, “extreme anxiety inhibits information processing and makes students less able to access memory, recognize patterns, analyze material and compose answers” (Nance, 2010, p. 33). Imagine if the literature students read incorporated elements of everyday speech patterns, the very patterns they encounter at home, in their community, or within the classroom among their peers. Students would come to recognize the naturalness of syllable simplification through methods like clipping, vowel raising, and elision, understanding them as valid forms of communication. This connection has the potential to engage students as they not only “see” the speech that they might use or hear but also relate to it.

Certain choices of literature not commonly found in the literary canon can have positive associations and eye dialect can spark that interest especially for those who consider reading like a puzzle, and have the drive to find the pieces to complete it. The type of analysis that students engage with regional literature is indeed a discovery, a puzzle that needs to be solved. Those that are not necessarily engaged with literature de la ciudad, may be able to identify with novelas de la tierra—because this type of literature represents spoken language with a textual code that needs to be broken. They can employ inductive reasoning to generate the rules for the non-normative output.

Pre-reading for dialecto literario

The pre-reading activity, or critical framing exercise, facilitates breaking the code to get to the other storyline (the plot), because one storyline is the code. In order to do that, students need to reconcile their sound to spelling expectations of normative language with the D2 sounds/orthography while also making categorical adjustments, much like a cryptogram: where “j”= “f” (an example of velarization) as in “jue” (fue) to indicate that the word is being pronounced (ˈxwe), or conditional adjustments (only in certain contexts) ø = “s” in syllable final /word final, but not in word/syllable initial position, such as “pue” (pues), but not in “sopa” or “casa” (syllable initial positions).

Sometimes there might be a merger of sounds, where two distinct phonemes converge in their allophony, for example, the glottalization of /x/ and the aspiration of /s/, both sound like English language “h”, so, regional “h” = orthographic “g”, “j”, or “s”. There will be other exceptions such as mergers which have even more complexity where “bu” and “hu” + vowel are both are represented as “gü”. As a result, “bueno” and “hueso” would be spelled “güeno” and “güeso” respectively. The duplicity of the “gü” construction is a potential stumbling block, but easily overcome once encountered and classified as an exception. An added advantage to the decoding process of linguistic phenomena is that the students can acquire regional cultural knowledge as well; they may identify the power imbalance between two interlocutors via the alternation of voseo, tuteo or ustedeo in the dialogue. The local regional vocabulary will also add to their receptive vocabulary by painting both a geographical landscape and a linguistic landscape. The words are already set apart by their notation: italics, boldfacing, parentheses, so many of the puzzle pieces that need special attention are already identified.

Moreover, in addition to the replacement of one letter for another, in rapid speech of any dialect of Spanish, clipping (shortening of words) is commonplace. Some linguistic environments attract clipping, acortamiento, more than others, for example, syllable final position since the preferred syllable structure of the Spanish language is the open syllable, without coda (consonant in final position). Nevertheless, although not as common, clipping can occur in initial word position, (apheresis): “bían” (habían); “brán” (habrán), in internal word position, (syncope): “trés” (traes) while the “s” is retained in final syllable position in this case; however, when it does occur in word final position, it is termed apocope, “pué” (pues). In Salvadoran regional literature, one can encounter “pue” or “pué” instead of “pues”, but “pos” in Mexican literature and, possibly “po” in Chilean literature. All examples digress from the normative “pues” even though they share the same contextual cues. Salarrué is not consistent with his coding of certain phenomena, as seen above in the “pue, pué” examples, and, that can complicate the students’ task. Other linguistic phenomena include: contraction: “ques, quen” (que es, que en), “noíjo” (no hijo); diphthongization: “ei” (“he”); and vowel raising: “ixaminé” (“examiné”). However, just like in speech, not all phenomena are realized 100% of the time. Variables, particular linguistic features, (lexical, phonetic, phonological, suprasegmental, morphological) and variants are alternate forms, such as different pronunciations of these variables. Salarrué presents variability in his writing just as variability occurs in the speech of the same speaker. It is not evidence of the lack of rules, on the contrary, dialects are rule-governed, but, factors such as fatigue, nervousness, emphasis, among others, all play a role in the surface form of language, so, adjustments for anomalous forms must be noted—somewhat similar to the same speaker who pronounces “often” with a silent “t”, but with an audible “t” at other times.

In addition to the eye dialect phenomena, some regionalisms may or may not be spelled in normative orthography, which present another layer of complexity. Salarrué oftentimes italicizes the Salvadorisms, alerting the reader to a special lexical form associated with the region, “arresto” (Salarrué, 2001, p. 19) or “tapexco” (Salarrué, 2001, p. 21). However, sometimes, linguistic phenomena of non-regional forms also carry the notation of italics, “perjumaba” (“perfumaba”) (Salarrué, 2005, p. 19), but not always, “siás” (“seas”) (Salarrué, 2005, p. 21).

In speech, context plays a more important role for comprehension because one is not influenced by orthography; misspellings may impact recognition and subsequent understanding. In regional literature, the non-normative orthography skews the understanding because readers do not immediately recognize the word, even a high frequency word. The challenge is that Salarrué italicizes both variables (regional lexical features) and variants (speech variations); however, other times, the variants are not italicized. Despite these inconsistencies, our students can read this form of literature, understand it, and be inspired to discover more about the regional dialect and culture. Moreover, the students notice that the seemingly imperfect (spoken) Spanish chastized in some circles is in fact of value because their knowledge of spoken Spanish provides them with the necessary background knowledge to recognize these novel forms and decode dialecto literario.

Readability

One’s ability to read different types of texts depends on several reader-specific factors such as background knowledge of the content, cognitive ability, memory, motivation, etc., but how “readable” a text is, or how accessible it is to an individual depends on text-specific factors, such as how the content is presented and organized or the choice of vocabulary (Brandl, 2008). One way to measure a text readability is to calculate sentence length and word complexity. While there are limitations with this type of calculation, it does offer some insights into how difficult a text could be. A low frequency word could be considered complex or if its meaning is not readily clear. Different readability scales (Fry Graph, Flesch, Lexile) attempt to determine what level of proficiency one might need to successfully read the text to match the reader with the most appropriate text. These measures are limited, however, because they do not necessarily account for regionalisms, polysemy, or eye dialect. Paul Nation (2006) determined that a reader needs to understand at least 95% of the text in order for comprehension to take place, but 98% is best--only 2 words out of 100 would be unknown, which represents a low density of unknown vocabulary. On the other end of the continuum is what is termed the frustration reading level and that is when the reader understands less than 76% of what they read (Dixon-Krauss, 1996, p. 144); this means that 24 out of 100 words would be unknown, a very high density of unknown words. In order to calculate the vocabulary density (number of unknown words/total number of words), one needs to ascertain what is an unknown word. This can be problematic due to polysemy and context, in addition to variation in linguistic proficiency among readers. The context can assist a reader in guessing the meaning, so that an unknown word does not hinder comprehension; however, if a word is known but it has more than one meaning, and the other meaning/s are not known, it actually should count as an unknown word. Miscues will occur when an unknown word (due to polysemy) is assigned the “known” meaning.

Preliminary Study

As a preliminary exercise to the study, the following word was given to all 18 students: “conocía”. The students were asked how many lexical items this word could represent if seen in a text. All 18 students wrote one word “conocía”. Then they were asked to pronounce it out loud and see if they felt that it was just one word that they heard. They still agreed that it was one word. Then they were presented with that same word pronunciation in three different contexts; they listened to the following sentences spoken quickly and then looked at the written text:

Él lo conocía cuando era niño.

Tú lo conocía (conocías) también.

Es conocía (conocida) por todas partes.

After hearing the pronunciation and then seeing the word, the students felt as though they had been tricked: “we may say it that way, but it is not spelled correctly in sentence 2 and 3!” Cleary, the orthography influenced their ability to use context to “see” what word they were hearing. Another question that arises is whether or not they “hear” the “s” and “d” in examples (2) and (3) respectively, or does the context provide that sound for them? So, it may be necessary to see the sounds, but it may not be necessary to “hear” them. This will be the challenge facing the readers of eye dialect; they will not “see” the letters that they are accustomed to seeing in written form, but they would understand the word in oral speech given the context. The students need to reconcile the absence of the normative orthography and rely on their speaking experience to help make meaning with these regional texts.

Study

Considering the first hundred words the selected text, “Semos malos”, the average number of unknown words for the students in the control group (A) of this study was 14.7, for the non-native speaking group (B) the percentage was 18.5, and the average for the alpha group (C) was 14.8, which would indicate that just roughly 85% of the text was understandable for groups A and C and only 81% for group B. This percentage falls roughly in between both the frustration reading level and the optimal reading level. These calculations did not take into account the title itself which caused significant difficulty because students had trouble understanding “semos”. In the online dictionary of the Real Academia, if one types in “semos” you will see: “La palabra semos no está en el Diccionario”. Unfortunately, standard dictionaries become useless tools because the word, as spelled, cannot be found; furthermore, in eye dialect, traditionally closed lexical classes, prepositions, pronouns, conjunctions, etc..., (that do not allow for new members), seem to be open classes: “dende, pa, endepué”, (desde, para, después). One would not expect to see new members in a closed class, so, those grammatical classifications do not often enter into the minds of students trying to guess meanings.

This small study consisted of one story from Cuentos de barro: “Semos malos”. The purpose was to see if heritage speakers could be more successful at understanding eye-dialect texts than their native speaker peers. The hypothesis was that heritage learners, equipped with the personal background knowledge of their own speech patterns, would be more successful at understanding and/or analyzing the multi-dialectal representations in the surface form and improve their ability to recognize and decode the text in similar literature of its type. It was the hope of the researcher that the alpha group in the study would be able to ‘evaluate’ more types of lexical ‘candidates’ and be better equipped to understand global phonetic phenomena and regional literature. Furthermore, they would be inspired to read more literary works, instead of being anxious by the non-normative spelling, and genuinely appreciate its cultural and linguistic richness.

A total of 18 declared Spanish majors from a Midwestern HSI public university participated in the study and formed three groups: Group A, the native speaker control group; Group B, the non-native control group; and Group C, the alpha group, the heritage speaker group. Group A consisted of six native speakers of Spanish from Mexico who came to the U.S. during their last two years of high school. Group B consisted of six native English speaking Spanish majors who began learning Spanish in high school. Group C consisted of six heritage speakers born in the United States of Mexican parents, who arrived in the US before their children’s birth, and spoke Spanish at home and took some Spanish classes in high school. All were taking the same 300-level Latin American literature class as a requirement for the major and eventually read this story as a part of their curriculum.

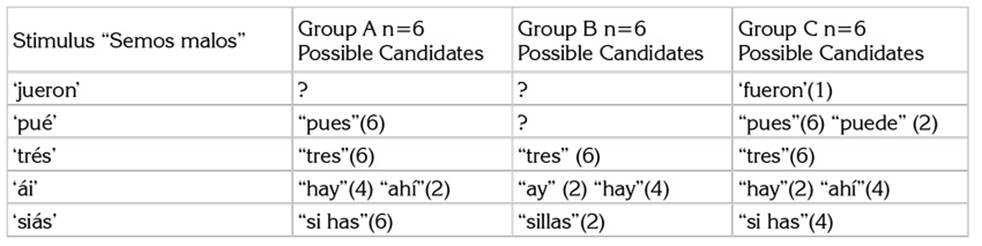

As a pre-reading activity, each group was first given a set of five isolated words taken from the short story “Semos malos” by Salarrué to see how they might fare with the non-normative spellings. The students were given a paper with two columns: in one column was the stimulus within quotation marks and the second column was blank for the students to fill in as many possibilities that they could think of for what the stimulus represented in normative orthography.

The results of the pre-reading activity, as shown in Table 1, were interesting, but not surprising. All groups were certain that “trés” was “tres”. It is notable, however, that none of the groups guessed correctly because the word is “traes”. All in all, without any context the guess was reasonable. Groups A and C were certain that “pué” was “pues”. For “ái” and “siás” the choice that the students might make would depend on the context, of which there was none provided.

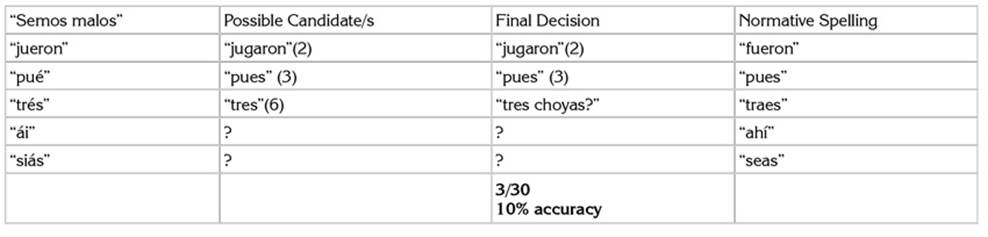

The second part of the pre-reading activity gave the students the entire sentence from where the word was extracted to see if that helped them to either provide the word that they could not guess in isolation, or to help them choose if they had more than one candidate. They were asked to use their results from the isolated task as a starting point for this activity and to confirm or disconfirm what they thought the word was (Possible Candidate/s), in isolation by analyzing it in context and decide if that word was right for the context (Final Decision), or to choose the appropriate word if they had more than one word in the “possible candidate/s” line. They were told to put a question mark (?) if they did not have a response, and, if they did have a response but were not entirely sure of it, then they were told to put a question mark (?) after the word. The instrument provided to each student was a piece of paper with four columns: the stimulus with the full sentence in column 1, the possible candidates from the first exercise and any additional ideas, the third column was for their final decision and the fourth column asked for the normative spelling. The full sentences can be found in Appendix 1. Their results follow in Tables 2, 3 and 4.

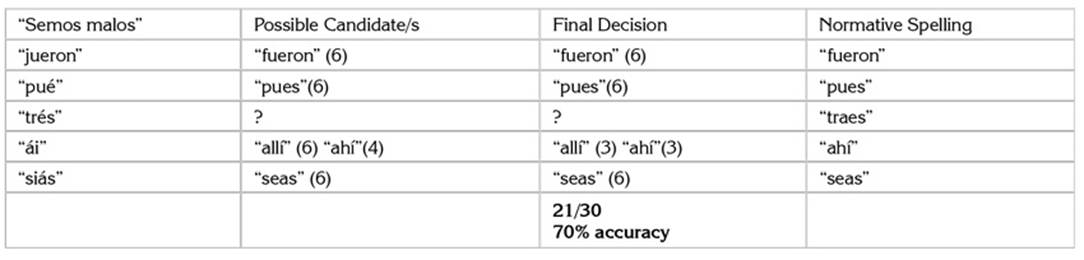

As shown in Table 2, Group A struggled with less commonly known phenomena, for example, most Spanish speakers are familiar with the aspiration or elision of the final “s” for the plural marker or the verb ending. “Trés choya” (traes choya) (Salarrué, 2001, p. 19) caused much difficulty, probably because “choya” was a regionalism with which they were not familiar. Group B students commented later that they thought that it should have been: *tres choyas, but they could not understand what that meant either. Each of the 18 participants had five lexical samples rendering a total of 90 samples. Only twelve were accurate, or 60% overall accuracy in Group A. Group B did not perform well, in comparison, with only three accurate, or 10% overall. Group C had performed much better on producing viable candidates, but was also perplexed by “trés choya”. Twenty one of the thirty were accurate, or 70% accuracy.

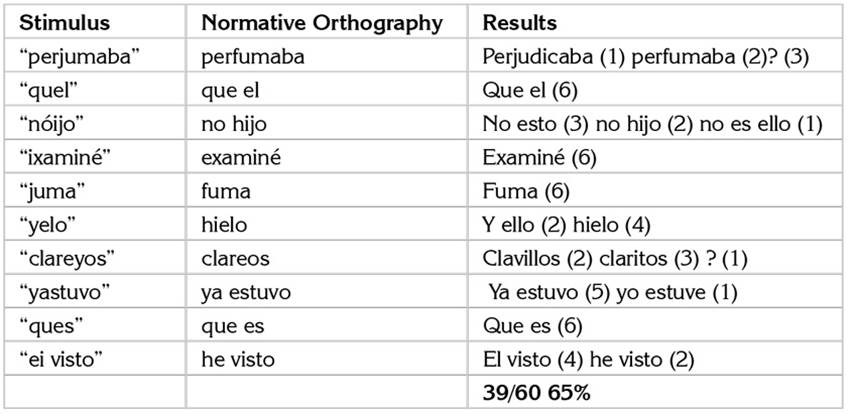

Furthermore, some members of Group C had more possible candidates identified for the stimulus in isolation: “pué” as either “pues” or “puede”. What is interesting about their selection of “puede” is that, in isolation, “puede” would make sense given the elision of the “d” and the resultant intensifying/lengthening of the “e”. Additionally, the stimulus “siás” prompted both “si has” and “seas” which could be viable candidates in isolation. Discussions followed in class about how “j” can replace “f”, one of the so called jejeo forms; how “i” can replace “e” and how the “d” between vowels, in particular, seems to disappear. The students took turns reading the text aloud and following along with the written text. After the students had read the text, they were given ten sentences from the text with a key word highlighted from the text and asked to give the normative orthographic form of the word. The full sentences can be found in Appendix 2.

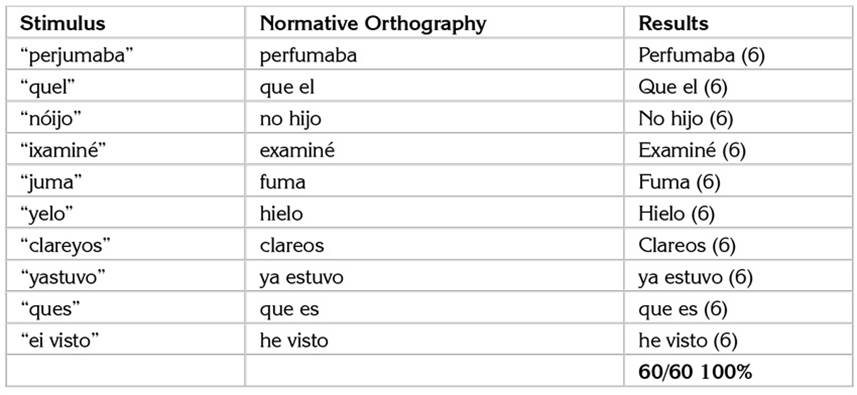

As shown in Tables 5, 6, and 7, the results of the post-reading were encouraging for all groups. Both Groups A and C scored 100% with Group B scoring 65%. The native-speaking and heritage-speaking groups (A and C respectively) were able to understand the selected samples of dialecto literario very well and even the English L1 speakers did well with a difficult text. If the students are not able to understand a regionalism or a non-normative orthographic form, their conversion from eye-dialect to normative orthography will allow them to locate the word in the dictionary, thus making the text more accessible; the decoding process makes the dictionary a viable tool again. When asked if they wanted to do their project on another story from Cuentos de barro, 50% of Group A (3/6) indicated that they would like to, only 17% (1/6) from Group B had interest, and 83% of Group C participants (5/6) decided to do their final research project on another story from the anthology. In sum, 50% (9/18) of the group were eager to learn more about the history of El Salvador during the time that Cuentos de barro were written.

Conclusion

Regional literature from Central America in general and El Salvador specifically is conspicuously missing from the literary canon and the literature classroom. Salarrué embeds Salvadoran history and culture in his collection, Cuentos de barro, and gives a voice and an identity to the campesinos who were historically silenced. The resulting eye dialect codes the speech phenomena of the Salvadoran peasant with the letters which represent the pronunciation, not the standard orthography. While both native and non-native speakers struggle with the odd spellings of eye dialect because they are not familiar with the underlying linguistic processes producing those variations, the text can be engaging and accessible to the students through proper pre-reading activities, or critical framing of the nonstandard orthography. The data collected from the current study showed that without at least sentence level context, students might only be successful with recognizing familiar lexical forms in isolation: “pue, ná”, (pues, nada). Moreover, regional forms that spell viable words in nonstandard orthography seem to complicate the outputs in isolation: “vía”, which could represent “vía” or “vida”, or “pecao”, which could be “pecado, pescado”. When inserted in the context of the text, however, the more appropriate candidate becomes obvious.

The D2, regional varieties, can be understood if students are equipped with the knowledge of orality, and they will be able to not only understand its allophony, but they can, quite possibly, predict it. This relationship between underlying form (normative orthography) and surface spoken form can be provided and explained by borrowing from Optimality Theory which shows how underlying forms are linked directly to their surface representations. The input (“pué”) passes through the ‘Generator’ producing a series of ‘Candidates’ (“pues, puede”), which pass through the 'Evaluator’ to determine which are viable forms given the context, “pues”.

In this case, the ‘Generator’ and the ‘Candidates’, can work independently of the context. However, it will be the role of the ‘Evaluator’ to assign the appropriate ‘candidate’ to the given context. Many students do not have this ability to process the viable ‘candidates’ from remote regional varieties which causes frustration and leads to defeat and possibly abandonment of the field of study. By addressing the negative “effects”, which result from not wanting to read literature or feeling unprepared for the task, students acquired a new skill set, a new mind set, and new dialects through exposure to underrepresented literature from Central America.

Students were eager to “read” more eye dialect literature and learn more about El Salvador’s history and cultures as evidenced by their selection of term paper topics for the course. The students also realized that once you are familiar with eye dialect formatting (schema), it is much easier to read eye dialects from other regions. The students found the task of manipulating the text back into standard orthography a rewarding and engaging activity. They were more aware of speech patterns and how consonants in Spanish are variable given their position in the syllable. The students also noted that unstressed vowels could change, vowel raising as well. More importantly, however, they also discovered that these indexical properties found in eye dialect literature are not always markers of class—they are phenomena that occur in certain syllabic environments with rapid speech. They could identify speakers of different dialects within their own circle of friends that exhibited some of these phenomena and they realize that even though those speakers do not normally alter the orthography when they write, they certainly pronounce the words differently than they are spelled.

Finally, the study allowed the students to see that exposure to another dialect can be additive, not subtractive; they do not have to change the way that they speak, but can keep this knowledge to help them understand other speakers and other cultures, “the job of school is to add a new layer to a child’s speech repertoire, not to undo the one they already have” (McWhorter, 2000, p. 15). These anomalous forms will be archived as receptive lexical items and, hopefully, they will be retrieved when generated in speech or represented in other regional literary works.

Heritage speakers who learn the Spanish language orally are uniquely equipped with content schema/schemata to better recognize dialecto literario and to decode the normative orthographical lexeme to which the unconventional spelling refers with scaffolding provided by linguistic decoding tools. The marginalized literature with dialecto literario, oftentimes criticized for its “immature” nature and special glossary, can be presented in the college classroom allowing the students to appreciate its cultural and historical richness with just a few linguistic decoding pre-reading skills. The importance of presenting the students with many forms of expression in Spanish is reinforced by Domingues Cruz, who states, “Hay que dar a conocer la magnitud de la historia, cultura y lenguas de México, Perú o Chile, entre otros países. Hay que presentar la coexistencia lingüística del español con otros idiomas o dialectos. Hay que prestar atención a culturas emergentes que son representa tivas de las mezclas identitarias de dos o más pueblos” (Domingues Cruz, 2019, p. 408). Regional literature that incorporates dialecto literario is one successful way of promoting knowledge of various dialects and speech phenomena while exposing students to some of the non-canonical literatures of the Americas