Introduction

Critical Interculturality (CI) is a political, social, epistemic, and ethical project that emerges in Latin America as a possibility of dialogue among cultures that goes beyond education to contemplate the construction of societies. There is also an increasing recognition of the importance of CI in the field of Foreign Language Teaching (FLT). Applied linguistic scholars (Álvarez Valencia, 2021; Álvarez Valencia & Michelson, 2022; Álvarez Valencia & Miranda, 2022; Canagarajah, 2023; Ferri, 2018; Halualani & Nakayama, 2010; Walsh, 2010a) have begun to discuss this term in relation to topics concerning social justice, decolonial perspectives, intercultural communication, critical frameworks for intercultural communication, Indigenous practices, context, issues of power, historical forces, and socio-economic relations. Other topics have to do with citizenship, multimodality, peace and coexistence, multilingualism, disability, crip linguistics, postmodernism, and cultural complexity. Publications about CI (Castro-Gómez & Grosfoguel, 2007; Mignolo, 2007; Quijano, 2014; Tubino, 2005, 2013; Viaña et al., 2010; Walsh, 2009a, 2010b, 2013; Zárate Pérez, 2014) involve discourses criticizing power and including Indigenous thought. They aim to promote members of diverse cultural groups in terms of their diversities and complexities, acknowledging the difference of each individual’s knowledge, being, and doing.

In Colombia, the field of FLT and learning is also beginning to embrace a critical intercultural perspective. Some Colombian ELT scholars (Álvarez Valencia, 2014; García & García, 2014; Granados-Beltrán, 2016, 2018a, 2018b; Núñez-Pardo, 2020a, 2020b, 2021; Usma Wilches et al., 2018) have addressed critical intercultural discourses depending on their interests and the context in which these issues take place. Theoretical knowledge and studies regarding CI have been a relevant and necessary initial development; however, it seems the teaching and learning practices of pedagogical experiences from a critical intercultural perspective remain at an early stage. It is highly probable that there are some critical intercultural experiences that have not had the chance of being shared or theorized about.

The authors of this article carefully followed a process to collect and analyze theory-based publications and research studies regarding CI and English as a Foreign Language (EFL) / ELT in Latin America and Colombia. To achieve this, the selection of the studies was carried out by searching using the following keywords: critical interculturality, decoloniality, pedagogical experiences, pedagogical practices, public schools, and different possible combinations thereof. The literature reviewed was located in national and international ELT journals. Book chapters and master and doctoral dissertations were also included. The articles were screened based on the keywords and eligibility criteria, resulting in a total of 64 publications, after deleting duplicate results. Then, to describe the intercultural pedagogical experiences, publications on teaching and learning approaches, and methods related to CI were also revised to support the description of the experiences.

Since CI is an ongoing construction in Latin America, and the two authors of this article position themselves from a geo-political location (Grosfoguel, 2011) in the same territory, this paper considers scholars and pedagogical experiences from Colombia and Latin America. Subsequently, this article is comprised of the following sections; first, we address the term CI based on the main Latin American tenets, as an ongoing project; second, we describe some studies from Colombian scholarship regarding CI and ELT and/or FLT; third, we characterize two critical intercultural cases in public-school scenarios in two regions in Colombia; finally, the article concludes by supporting other scholars’ claims about the importance of bringing critical intercultural discourses into FLT and learning practices, as shown in the two cases. Furthermore, it is concluded that the concept of CI is still being developed in Latin America and Colombia, and that bringing authentic critical intercultural experiences to the discussion allows us to move beyond mere critical intercultural theory.

Critical Interculturality in Latin America: A project

Different authors highlight the importance of moving from the concept of interculturality to Critical Interculturality (CI) (Quijano, 2014; Tlostanova & Mignolo, 2009; Tubino, 2005, 2013; Zárate Pérez, 2014). This arises from the need to understand education from a socio-political and ethical perspective in which there are opportunities to question and reflect on traditional power dynamics. Thus, listening to voices from communities that have been marginalized is necessary. Nevertheless, this concept has different connotations in particular scenarios; Tubino (2005) states that in Latin American countries, CI appears as a need to reposition Indigenous communities bearing in mind that language is an important issue in bilingual programs.

López and Sichra (2008) describe how the implementation of Intercultural Bilingual Education (IBE), among other academic topics involving Indigenous languages and learners from these communities, is part of an intercultural project. However, different intercultural bilingual programs in Latin America have actually served to widen cultural gaps by classifying people as Indigenous or non-Indigenous (Viaña et al., 2010; Walsh, 2009a, 2010, 2013; Zárate Pérez, 2014). It gives a mistaken message indicating that those who need to become intercultural subjects are the Indigenous groups and not the so-called ‘civilized’ groups. This mistaken conception of intercultural bilingual programs opens up new possibilities, in which bilingual programs can be envisioned from a critical-intercultural perspective to target the needs of diverse regions and populations in the country.

CI implies the construction of a political, ethical, social, and epistemic project oriented to decolonize and transform realities with collective actions at the social and historical level (Granados-Beltrán, 2022; Walsh, 2007, 2009a, 2014). Likewise, Castro-Gómez and Grosfoguel (2007) argue that CI has to do with contributing to transforming subjects to become critical voices for the world. Moreover, Mignolo (2007) states that CI has to be understood as part of the decolonial theory that emerged in Latin American countries against dominant ideologies. As stated by Walsh (2009b), CI is in a process of construction and does not exist at this moment. This is a project that questions the system and looks for a social change to decolonize and give voice to marginalized groups and minorities.

Walsh (2009a) , 2009b, 2010a, 2010b) debates the coloniality of power, knowing, and being as part of CI. We will first refer to the coloniality of power, which is supported by a capitalist perspective that represents the hierarchy of power and a Eurocentric level of superiority in all scenarios. This coloniality arises as a consequence of inequalities pertaining to the distribution of goods and wealth, race, economic opportunities, level of education, affiliations, religion, governmental decisions, among many others (Quijano, 2000). Second, the coloniality of knowing arises from the perception that knowledge comes from a Eurocentric and unidirectional way of conceiving and understanding the world (Mignolo, 2007; Walsh, 2007; Zárate Pérez, 2014). This implies that knowledge is produced as a result of the lived experiences in Northern countries (USA, Canada, England, nations of the European Union), as their culture is considered the backbone of human evolution. Without a doubt, this diminishes the possibility that the knowledge produced in countries of the global south might receive equal legitimization. Third, the vestiges of the coloniality of power and knowing derive in the coloniality of being, which implies a sense of subordination where the individual is minimized and oppressed (Walsh, 2009b, 2010a) by the material and symbolic forces implanted by colonial powers. In this regard, there is a need to reposition the other, leaving aside sexist, racist, and linear social class discourses.

In the realm of CI within Latin America, a number of significant tendencies emerge. First, the transition from relational and functional interculturality to CI is seen as vital. This shift underscores the importance of questioning traditional power dynamics and amplifying marginalized community voices. Second, CI gains particular relevance by aiming to empower Indigenous communities, particularly in bilingual programs. However, a critical view reveals that some of these programs unintentionally deepen cultural divisions. Consequently, CI offers a way to reconceptualize Latin American bilingual programs, aligning them with a critical intercultural perspective. Finally, as a multifaceted project, CI seeks to decolonize and transform various realities through collective actions. It empowers marginalized groups and challenges dominant ideologies, critically examining the coloniality of power, knowledge, and being, rooted in capitalist hierarchies, Eurocentric knowledge production, and individual subordination. In essence, CI in Latin America emerges as a transformative force challenging the status quo and advocating for inclusivity, equity, and decolonization in the region.

Critical Interculturality in ELT Colombian scholarship

This section begins with an overview of some studies concerning interculturality and how this notion is increasingly studied and implemented by Colombian academics who work in ELT. Then, we draw on critical intercultural research that is taking place in the country. Some Colombian scholars argue that interculturality is at a nascent stage in the country (Álvarez & Bonilla, 2009; Álvarez Valencia, 2014; García & García, 2014). Nevertheless, these authors agree that studies published by Colombian researchers show an increasing interest in the teaching-learning of intercultural awareness. Colombian publications on interculturality allow us to understand different cultural and social realities (Álvarez Valencia, 2014; Fandiño, 2014). Álvarez Valencia (2014) proposed that we reconceptualize culture and intercultural communication, while Arbeláez and Vélez (2008) discussed interculturality in relation to Ethnoeducation in Colombia, and concluded that it should be considered imperative at all academic levels and for all groups that form part of a nation.

In the same vein, a research on intercultural sensitivity in bilingual education was conducted in Bogotá by de Mejía and Tejada-Sánchez (2020). The aim was to highlight the importance of preparing language teachers for intercultural encounters, both in their personal lives and in their role as teachers, helping them to understand the potential for developing intercultural sensitivity among their students while teaching languages. More recently, Peña Dix (2023) postulated a relationship between interculturality and intercultural communicative competence, teaching languages, and ELT. The author argues that interculturality has proved to be challenging for teachers. The expectation is that teachers should focus on developing not just learners’ linguistic competence, but also intercultural communicative competence. The teaching of languages appears as a scenario to genuinely develop intercultural communication and dialogue, leading to harmonious relationships and global and intercultural forms of citizenship.

Doing research on critical interculturality can pose a challenge because although researchers might be willing to embrace decolonial theories, they are forced to re-think their positionality towards new ways of being, knowing, and power. Despite this, Critical Interculturality (CI) is being studied by different scholars (Granados-Beltrán, 2018a, 2018b; Núñez-Pardo, 2020a, 2020b, 2021; Ramos-Holguín, 2013, 2021). For example, Granados-Beltrán (2018a, 2018b) has indicated that CI, from a decolonial standpoint, “can support initial foreign language teacher education ontologically and epistemologically” (Granados-Beltrán, 2018b, p. 10). The author highlighted different tensions that emerge from language teaching programs and novice teachers’ perceptions in connection with coloniality. In a similar manner, Ramos-Holguín (2013, 2021) has demonstrated that language teachers begin to develop consciousness of intercultural competence after interpreting and contextualizing cultural practices and understanding the complexities of different contexts. Likewise, Núñez-Pardo (2022) has suggested that there is a need to continue exploring students’ and teachers’ perceptions to understand them as the result of beliefs, practices, and experiences from interaction in different teaching and learning environments. These previous studies showcase the importance of resisting hegemonic and predetermined knowledge presented by some language teachers based on Eurocentric perspectives.

Applied linguistic scholars in Colombia are starting to connect CI with studies that involve Indigenous students in universities. Usma Wilches et al. (2018) has asserted that critical positions towards interculturality imply the recognition of intercultural dialogues when equity is guaranteed. A small group of participants involved in Usma Wilches et al.’s (2018) study acknowledged that cultural identity is associated with community and languages. Similarly, in a study by Álvarez Valencia and Miranda (2022) , principles of CI were reviewed in light of a decolonial view to explain the position of students’ intersectional subjectivities, communities, and languages, and to examine how Indigenous students engage in agentive actions to resist colonial practices. This is connected to the repositioning of Indigenous communities from a CI perspective.

CI in Colombia has been studied in connection to different disciplines, such as multilingual education, language education programs, diversity, multimodality, and social semiotic discourses. García and García (2014) suggested that bilingual education in a globalized society should be based on a critical intercultural perspective. In addition, Granados-Beltrán (2016) mentioned the relevance of making connections between teaching languages and CI as a decolonizing political and epistemic project. In this scenario, society is expected to recognize the being and knowing of diverse communities. In line with this, Álvarez Valencia (2021, 2023) has discussed the relationship between multimodal social semiotics and a more detailed view of interculturality, beyond a transnational approach, by looking at the classroom ecology as an intercultural space where students deploy their cultural semiotic repertoires. Thus, Álvarez Valencia and Michelson (2022) have adopted a critical perspective to interculturality, drawing on social semiotics to explain that intercultural experiences are meaning-design processes taking place in interactions with texts involving multimodal semiotic resources.

The previous studies presented in this section, reveal some tendencies concerning critical interculturality in Colombia. First, they evince a growing interest in interculturality within ELT in the country, with an agreement among academics that intercultural awareness is becoming more important in the field of FLT. Second, researchers are embracing decolonial theories and challenging Eurocentric perspectives in education as they move towards CI. Third, the studies allow us to understand that CI aims to dismantle hegemonic knowledge and confront colonial practices while fostering intercultural encounters. Nevertheless, researchers acknowledge that conducting research on critical interculturality poses a challenge, as it compels the authors to reconsider their own positions and embrace new ways of understanding being, knowing, and living. Finally, the studies emphasize the need for careful decisions when planning and implementing language-teaching education programs, recognizing the importance of educating, bearing in mind diversity and plurality to engage with social issues of power and promote equal relationships. This trajectory reflects a promising evolution in Colombia’s educational landscape, encouraging more inclusive and interculturally sensitive approaches to teaching and learning.

Critical Intercultural Pedagogical Experiences: The case of two public schools

The case of Medellín, Antioquia

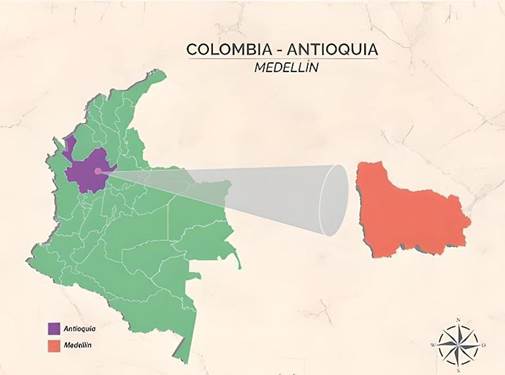

Medellín is the capital city in the department of Antioquia. Officially, Medellín is the second largest city in Colombia, located in the Aburrá Valley. This city is part of a central region in the Andes Mountains in South America (see Figure 1). Currently, there are 129 public schools in Medellín. The average class size varies between forty and fifty students who attend from Monday to Friday in morning and afternoon shifts. This pedagogical experience takes place in Robledo, a neighborhood designated as Comuna 7 in Medellín. This neighborhood is located in the north-western part of Medellín with an average stratum of 3 on a scale from 1 to 6. Institución Educativa Mariscal Robledo caters to students at the elementary and secondary levels.

The English language is one of the subjects offered in the school curriculum. The English teacher of the tenth and eleventh grades, one of the authors of this paper, has integrated a Critical Interculturality (CI) perspective into her class. The teacher started by identifying students’ needs, contexts, and interests. Consequently, together they raised awareness of the violence that Medellín suffers from different criminal organizations. An example of this reality is the BACRIM (Bandas Criminales) in Colombia, a term which refers to different criminal groups that have been described as a threat to Colombia (McDermott, 2014). BACRIM are well-known and classified as criminal organizations in Medellín. This reality favors inequalities and poverty, as well as threatening the peaceful coexistence and environment within some public schools.

CI is attached to social justice discourse. Some theoretical tenets of CI according to researchers such as Arbeláez & Vélez, 2008; Granados-Beltrán, 2016; López & Sichra, 2008; Muñoz, 2002; Tubino, 2004; Walsh, 2003, 2007, 2009a, 2009b, 2012; Zárate Pérez, 2014, favor social justice when acknowledging students’ realities and inequalities without privileged power in their cultural practices. The CI perspective in this case was embraced by the language teacher as an opportunity to enable spaces and efforts in the school to work on students’ issues concerning the socially unjust agenda in the city. Likewise, Colombian scholars (Carvajal Medina, 2020; Mojica & Castañeda-Peña, 2017; Ortega, 2019; Paredes-Méndez et al., 2021) confirm the relevance of this topic regarding English language teaching and learning. The authors agree that linking social justice to English language classes offers the possibility of re-imagining ways of communication, as it provides a space that considers different voices, not only one.

As a consequence of this series of contextual realities and the critical perspective of the language teacher in the public-school system in Medellín, a didactic unit was planned at the beginning of 2022 to be developed in three different terms throughout the year. The unit was entitled “Social Justice-Inviting to Peace”. Since critical intercultural perspectives do not promote specific models or frameworks to be followed, the language teacher took into consideration some approaches aligned with the view of CI already described in this article. The first approach was culturally responsive teaching, a situational and contextual process of teaching and learning for both teachers and learners (Taylor & Sobel, 2011). This perspective implies the teacher’s commitment to students’ diversity of cultures, languages, racial/ethnic backgrounds, economic resources, religions, abilities, interests, and life experiences. Another was place-and-community based education (Smith & Sobel, 2010), which connects learning to the alienation of students from the real world right outside their classrooms. Place-and community-based education takes into account students’ understandings linking their local situations with their learning.

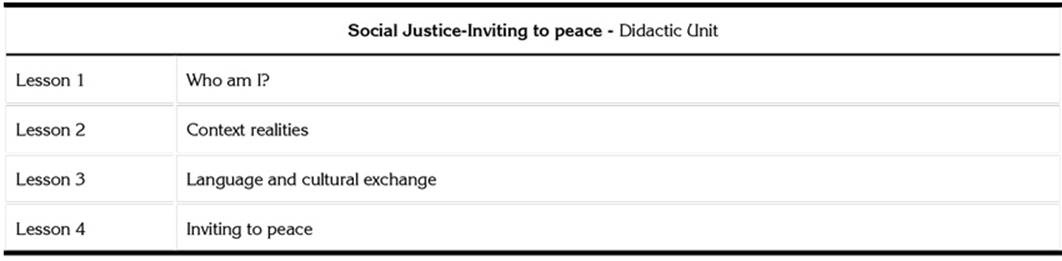

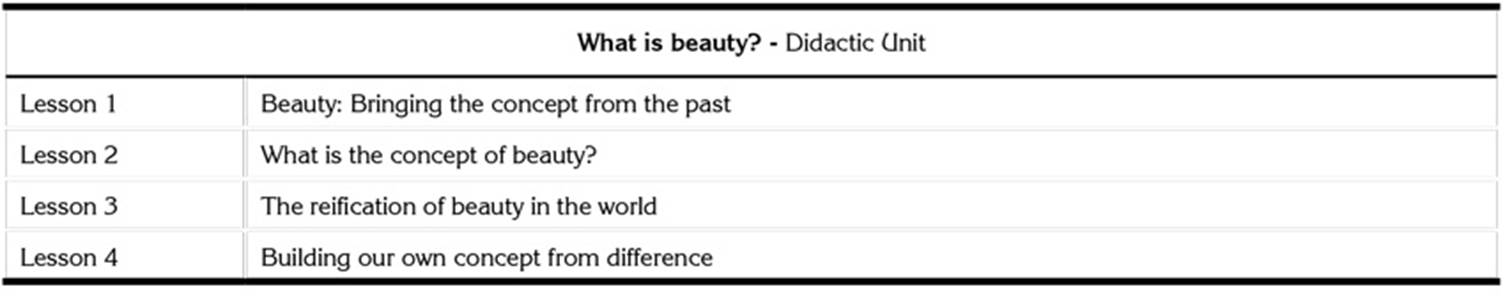

Table 1 presents the structure of the Didactic Unit and the four lessons implemented throughout the year. The teacher gave a description of the intercultural context of the institution to be considered in the lessons she planned, addressing points such as the name of the school, the students’ grade level, the multilingual classrooms (Spanish and English languages), and the number of students per class with around 42 students in each. Their social stratification was also described which oscillated between 2 and 3 in a scale from 1 to 5.

The main purpose of the didactic unit was to recognize students’ identity and role concerning social, national, and local situations by exposing them to authentic resources and realities in relation to discrimination, the war in Colombia, human rights, and social justice. The skills to be developed were language skills, communication, cooperation, and empathy. All the objectives were cross-referenced with the Basic Learning Rights for English language (MEN, 2016) in the tenth and eleventh grades. Moreover, they were written from a critical intercultural perspective. The unit included four different lessons, each beginning by activating students’ prior knowledge.

The first lesson was Who am I? To start this lesson, students were asked to produce a written narrative piece by using parts of speech and their context vocabulary (school, neighborhood, city) to make a summary of who they are, their characteristics, and their relationships with others. At the end of this lesson, students discussed the narratives. In addition, they shared if they felt (or did not feel) identified as subjects of peace. In the second lesson, Context realities, the learners were asked to reflect on other positions concerning peace by discussing national issues such as the war in Colombia, while developing English language oral and listening skills. As part of the activities, students created a poster inviting reflections about the reality of war in Colombia. In the third lesson, Language and cultural exchange, the objective allowed learners to exchange language and cultural conversations with students from a public school in California, in the United States, by using simple structures of the language to refer to themselves, the place they lived in, and social realities in the country, speaking in Spanish, English, or other languages in the classroom. During this lesson, students had the opportunity to talk online with other high school groups about the context, territory, and social realities of every city/state they belonged to. Lastly, in the fourth lesson, Inviting to Peace, the learners were allowed to create their own artifacts on Social Justice-Inviting to Peace. Then, they shared posters, narratives, videos of their cultural exchange, and their reflections and positions regarding the situation of war in the country. For instance, Figure 2 shows a poster created by a tenth grader inviting the world to live in peace. In this final assignment, students made short videos in class, inviting parents and other members of the community to raise awareness about equality and social justice in Medellín and the wider country. While sharing their work, they talked about how they identified (or did not identify) themselves as peace ambassadors in their school, and in the local and national territory.

The kind of assessment during this didactic unit involved both formative and summative approaches, but with a major emphasis on the formative process by means of short narratives, reports, self-description of their role in their context, cultural exchange practices, and new and authentic material created by students. Intercultural objectives were also established. Among those, the main goal was to recognize students’ identities and roles concerning social, national, and local situations by exposing them to authentic resources and realities regarding discrimination, the post-war situation in Colombia, human rights, and social justice. Furthermore, one of the specific objectives was to reflect on both their own positions concerning national and local situations around them as well as those of others.

The implementation of the “Social Justice-Inviting to Peace” didactic unit deeply influenced the students at Institución Educativa Mariscal Robledo in Medellín. As they embarked on this critical intercultural journey, they seemed enthusiastic for their English classes and found a powerful venue for self-expression and exploration of their own identities. Through meaningful discussions, narrative sharing, and cultural exchanges, students actively engaged with the English language and the established objectives, and began to raise awareness about the social issues affecting their city and country. Their active participation in crafting posters, videos, and reflections transformed them into advocates for social justice and peace, both within their school and the broader community. Even as the students engaged with the lessons, it is important to note that during this transformative journey, some students expressed their concerns, what they considered problems and contradictions among their families, neighbors, school, and other closed environments. Some of them openly shared that they sometimes felt ashamed due to the harsh realities they faced. At times, during the discussions, some of the learners used words like ‘hopeless’ and ‘sadness’. However, this didactic unit not only enriched the language skills of the students, but also served to foster a sense of empathy, cooperation, empowerment, and critical intercultural vision, making them proactive agents of change in the pursuit of equity and a more harmonious society.

The case of Florencia, Caquetá

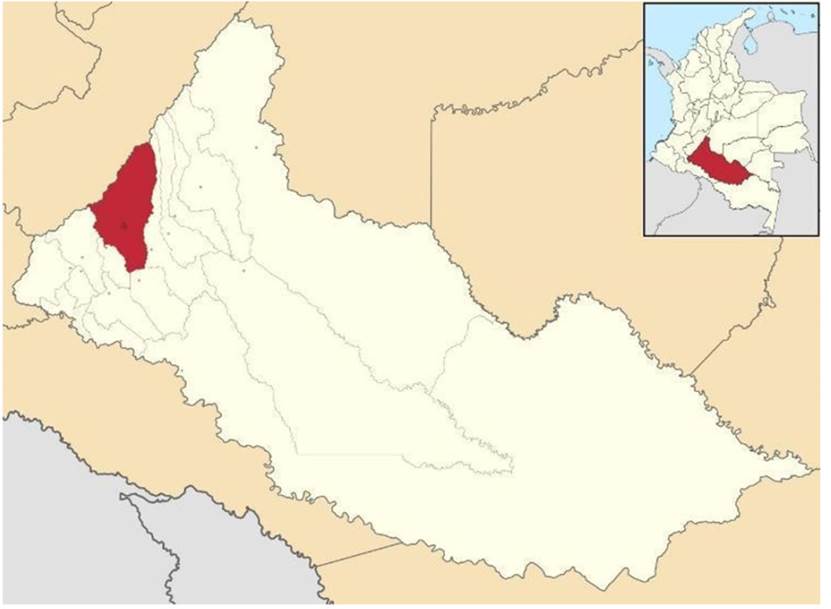

The department of Caquetá is a region that has traditionally been marginalized due to it being a conflict zone that also suffers from a lack of attention from the government. It has been the home to different settlers who came from other regions in the country. These settlers colonized this unexplored Amazon region because of its rich variety of natural resources. Caquetá is now the home of around 483,846 inhabitants. Florencia, known as the golden gate of the Amazon region, is the capital of this green department (see Figure 3). There are around 173,011 inhabitants living in this capital city. Although the population in Florencia is the result of decades of conflict, displacement from rural areas, and difficulties passed on from generation to generation, Florencianos have taken every opportunity to contribute to the development of their region. Currently, there are 31 public schools in Florencia, and the number of students per classroom varies between thirty-five to forty-five depending on the infrastructure of the school.

CI, taken as the possibility to reposition beliefs and transform realities, is part of what is taught at the school level in Florencia. In this respect, there are several different initiatives that are taking place in a public school in this region: Institución Educativa Barrios Unidos del Sur. This is a public school located in an urban area in Florencia. There are 2300 students ranging from preschool to eleventh grade. The school population belongs to socio-economic strata 1 to 3. As part of the curriculum, students take EFL lessons three hours per week. To name one experience regarding CI in the EFL lessons, there is a group of tenth graders who have worked on the topic of beauty in their lessons. Materials Development (MD), as part of one of the urgent calls to create and develop materials (Núñez-Pardo, 2020b). This creates opportunities to transform students’ possibilities to generate and create meaning based on their own experiences and those of others. The concept of beauty was used as a medium for the investigation of the diversity of perception. Learners examined perceptions of beauty from other cultural groups around the world; they were then able to construct their own concept of beauty based on their knowledge and experiences by understanding what others think about the topic.

CI was the main theoretical construct in the development of a didactic unit for these tenth graders. Moreover, the curriculum in this public school called for the use and implementation of the English, Please! series, a textbook provided by Ministerio de Educación Nacional (MEN) for public schools. In this case, the section What is beauty is part of the proposed topics in the workbook for tenth grade. This didactic unit was developed following the frameworks for creating and adapting materials (Núñez & Téllez, 2009; Núñez et al., 2012), the ontological, epistemological and power criteria for the development of materials (Núñez-Pardo, 2020b), and the so-called cultural knowings as coined by Moran (2001) . As a result, these moments were stated as needs analysis, setting the objectives, selecting the content, selecting and developing the materials (four lessons), organizing activities, assessment, and evaluation. The selection of the topic and subtopics for the four lessons (see Table 2) in the didactic unit was carried out by following the proposed topic in the textbook and the cultural knowings envisioned by Moran (2001): knowing about, knowing how, knowing why, knowing oneself.

There are intercultural objectives that framed the development of this didactic unit. The general objective was to critically analyze different concepts of beauty from different communities around the world so students could build their own understanding of beauty. The subsidiary objectives were (a) to describe people from different communities around the world, (b) to critically compare different concepts of beauty from different communities, (c) to critically contrast different concepts of beauty from different communities, (d) to reflect on their own concepts of beauty and those of others, and (e) to build their own understanding of beauty from the difference with others.

What is beauty? was developed for the second term of the academic year 2022. The average number of tenth graders per group was 30 and the length of each lesson was two hours for a total of eight hours for the whole didactic unit. The language focus was adjectives (order of adjectives), use of ‘have to’ and ‘do not have to’ to express obligation, and the structure of paragraphs, including topic sentences, supporting ideas, and conclusions. The development of this unit also considered the following Basic Learning Rights (BLRs) suggested by the MEN (2016): “exchanges opinions on topics of personal, social, or academic interest” (p. 23) and “explains ideas presented in an oral or written text about topics of interest or that are familiar through the use of previous knowledge, inferences, or interpretations” (p. 22). Although Task Based Learning (TBL) might be considered a traditional approach for language learning, TBL offers the possibility to integrate elements from CI to develop tasks with students.

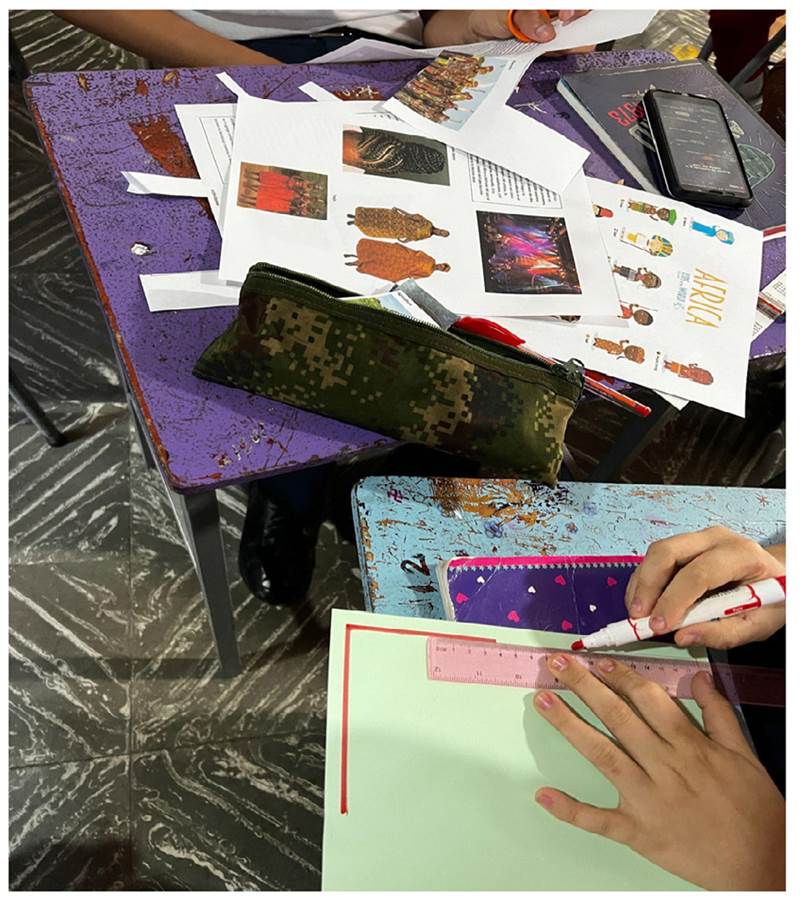

In lesson 1, Beauty: Bringing the concept from the past, the tasks included elements to activate prior knowledge, introduce relevant vocabulary, explore the concept of beauty in societal and cultural groups from other countries, listen to the voices of others regarding what they considered beautiful, read about the concept of beauty throughout history, and construct students’ own concepts of beauty in a short paragraph. In lesson 2, What is the concept of beauty? the tasks included sharing ideas from the paragraphs written in the previous lesson, reading about the concept of beauty in four communities in Indonesia, Myanmar, New Zealand, and Mauritania, getting familiarized with exercises for the Saber 11 test in relation to the topic, and interviewing relatives at home. In this part, the approach of students as ethnographers (Beach, 1999; Hough, 1998) and funds of knowledge (Moll, 1992, 2005; Moll et al., 1992) were considered. In lesson 3, The reification of beauty in the world, the tasks included sharing the experiences from the interviews, discussing how society has reified the notion of beauty by stereotyping people, watching different videos, reading two short articles, and then, re-considering students’ personal stance on beauty after these lessons. Finally, in lesson 4, Building our own concept from difference, the task was to present a poster, diagram, infographic, mind map, picture, and/or collage emphasizing their own conceptualization of beauty after these lessons. In Figure 4, students worked on the design of a poster in which they built their own concept of beauty. Generally speaking, the different tasks in the four lessons allowed students to interact and create meaning by integrating different intersemiotic and multimodal resources (Álvarez Valencia, 2016, 2021; Bezemer & Jewitt, 2010; Kress, 2012; Machin, 2016). At the end, students also took part in a self-assessment strategy called traffic lights in which they were invited to assess their performance in the lessons by using the green, yellow, and red palettes to indicate agreement, neutrality, or disagreement towards some statements from the lessons and the complete didactic unit.

Without a doubt, the implementation of the didactic unit “What is Beauty?” with tenth graders at Institución Educativa Barrios Unidos del Sur in Florencia, Caquetá, had a notable impact on them. Throughout the course of these lessons, students displayed a heightened interest in their English lessons, embracing the opportunity for self-expression and a deeper exploration of their own way, as well as other ways, of conceiving the world. By encouraging students to critically analyze different concepts of beauty from various communities around the world, these lessons not only expanded their intercultural awareness but also encouraged them to reflect on their own perceptions and biases. Furthermore, the incorporation of interactive tasks, interviews, and posters empowered students to actively participate in the learning process, promoting their language skills and critical thinking. Subsequently, the students transformed into agents of change, challenging stereotypes and fostering a sense of empathy from a critical intercultural place. It is evident that this didactic unit contributed positively to their language learning experience and provided a platform for exploring and discussing important social and cultural issues.

Conclusions

Latin American scholars understand Critical Interculturality (CI) as an ongoing project with a political, ethical, social, and epistemic stance. This is one reason why Latin Americans started questioning vertical academic systems to propose new methodologies that cater to students’ needs and real conditions. This reality represents an opportunity to conceive of CI as the construction and repositioning of other forms of power, knowing, and being. Colombian scholarship has also led the vanguard in the exploration of CI in the FLT and learning field. In this respect, the concept of CI has been addressed mainly by researchers in tertiary education. These researchers have studied different academic contexts, such as rural and urban territories, universities, and schools. Even though Colombia has also experienced imperialism in methodologies and pedagogical experiences that come from English-speaking countries, Colombian researchers suggest it is important to consider contextual realities and to create new ways to implement CI in scholars’ scenarios.

CI remains a means by which to transform realities by questioning systematic structures of power, and research in this area has included topics such as multimodality, multilingualism, EFL textbooks analysis, teacher education programs, Indigenous university students, race, and decolonial perspectives. CI also stems from the need to reposition other understandings. The critical revision of the literature included in this article reveals that more theory than praxis exists on the subject of critical intercultural experiences. Thus, the authors invite readers to proceed in their language teaching and learning in relation to CI from a reflexive position. This can be achieved by recognizing the other and giving value to the cultural differences that facilitate a critical intercultural vision of the world.

This article has established that CI is still in a process of construction involving a variety of well theorized studies. However, these efforts are not sufficient unless practical actions translate into educational contexts. This is the reason why bringing authentic critical intercultural experiences to the stage is a chance to move beyond mere theorization. In the case of these authors, the intersection between praxis and CI enabled us to take action and transform students’ beliefs, interests, modes of thinking, and meaning-making in two public schools in Colombia. In the first instance, a project-based community plan was applied in one public school in Medellín. It addressed social justice issues in CI to transform students’ local interests and realities in a city marked by violence. Throughout this process, students were able to raise awareness of their realities, to understand the role they want to play in their context, and to have the possibility of understanding the thinking of others to lead peace practices. In the second instance, an EFL teacher in a public school in Florencia implemented a didactic unit to discuss the concept of beauty from a critical intercultural perspective. This controversial topic made students reflect on how other cultures perceived beauty and how differently this globalized world can portray an ideal of beauty. The chance to interact with their classmates and their relatives at home, to read and investigate, to listen to other voices, and to question themselves and their own beliefs helped students to reshape their understanding of beauty, a concept that now remains for them dynamic and in constant reconstruction and consideration.

There are limited CI practical experiences that evidence how teachers are putting this notion into practice in their respective academic contexts. It is true that teachers at different university and school levels take important actions in their immediate settings. Thus, their own voices as well as their students’ voices can be listened to by others who are eager to transform their communities. All in all, the authors encourage school language teachers to document their own pedagogical experiences. It is the authors’ hope that local authorities will support language teachers with training, economic resources, and time so that they may be able to write about the pedagogical experiences that are taking place at schools, as many of them are not shared