1. Introduction

Compared with men, the number of women in positions of organizational leadership is low. Despite positive movement of women into upper management roles in organizations over the last fifty years (Eagly & Carli, 2007), there are still significantly fewer women than men leading organizations (Leonard, 2013). This occurs although women earn more undergraduate, graduate, and terminal degrees than men (Gonzales et al., 2013), suggesting that women strongly desire achievement and recognition; nevertheless, a gender divide leaves women outside many of the most powerful leadership positions in organizations.

When women do lead, they often have less responsibility than men (Eagly & Karau, 2002), are less represented on corporate boards in certain regions (Thams, Bendell, & Terjesen, 2018), and earn less pay (Wiler et al., 2022). Women are more likely to serve in assistant-type positions than their male counterparts, who still hold over 93% of CEO positions in Fortune 500 firms (Fortune, 2017). On average, men still earn over twenty cents per dollar more than women for the same job (Hegewisch & DuMonthier, 2016). Masculinity continues to dominate in business organizations, with women battling upstream against it by fighting blatant and subtle gender discrimination (Solomon, 2013). While current social movements attempt to focus awareness on the frequency of sexual harassment and sexual assault in the workplace (Hendrix, et al., 2018), women often are hesitant to challenge manifestations of discrimination for fear of repercussions that could negatively affect their careers (Sakoui, 2017).

Further, as women speak out about the proliferation of gender discrimination in technology, media, entertainment, and other fields (Zarya, 2017), something else becomes apparent: they are discouraged from advancing into top leadership positions. Not only must women frequently endure sexual harassment, but also the organizations they work for often overlook and ignore them when recruiting for leadership positions (McLaughlin, et al., 2017). Women leaders are as capable as men, although they are often considered to be less so (Sánchez & Lehnert, 2019). Research has reliably shown that women leaders are associated with strong economic and social performance (Galbreath, 2018), and a trustworthy working environment (Zhang & Hou, 2012) that emphasizes employee feedback and development (Melero, 2011).

While much research has been done on women in and out of leadership (Shen & Joseph, 2021), there is limited understanding of how perceptions of women as leaders affect an organization's performance. Our work explores the perception of women in leadership and how those perceptions interact with organizational trust and performance. We look to continue the development of theory to address some of the reasons why people may perceive differences between women and men as leaders. We argue that organizational relationships are built on trust and suggest that organizational trust is a variable that might explain implicit biases about women's leadership abilities across genders.

Our intent is to contribute to the research on women in organizational leadership, highlighting how organizational trust can influence how employees perceive women as managers and organizational performance. This paper then attempts to contribute to developing theory on the relationship between gender and employee perceptions. By highlighting a distinction that is often ignored in the literature, we explore how employee gender affects their perceptions of women as leaders, specifically if the perception of women leaders varies between men and women employees. Our results lend support to the need for firms to build on organizational trust to promote gender diversity in leadership roles (Joshi & Diekman, 2022), recognizing the challenges that both men and women face as they aspire to be and become leaders.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1 Trust, Gender, and Women as Leaders

Leaders of an organization may set a strong corporate culture and tone, but it is developed, maintained, and implemented by the firm's employees. Employee perceptions of leadership, including the abilities of women in those leadership positions, are critical to framing and maintaining an organization's culture. Employee perceptions of a company's authenticity of its leadership, job satisfaction, and work flexibility affect organizational culture, because the strength of those attributes exemplify the firm's values (Azanza et al., 2013). Building trust in the organization is foundational to building a strong culture (Wang & Hsieh, 2013). When employees trust their firm, they are more likely to embrace internal and external strategies and decisions, the corporate culture, and its perceived outcomes (Fukuyama, 1995; Wang & Hsieh, 2013).

Trust is "the mutual confidence that no party to an exchange will exploit another's vulnerability" (Sabel, 1993, p. 1133). It includes notions of competence, openness, and reliability (Fukuyama, 1995), and can determine how employees perceive strategic decisions and firm performance (Korsgaard et al., 1995). High organizational trust helps the achievement of organizational goals (Mayer et al. 1995); it also influences how people view their firm's reputation, performance, and social standing (Shockley-Zalabak et al., 2000). At its most fundamental, trust is the "preparedness to be vulnerable" (Bevelander & Page, 2011), and the confidence we place in something when we cannot fully control the outcome.

Employees put their trust in their workplace, recognizing that firm strategies involve risks that are likely to affect them; perhaps negatively. Employees want to trust that their firm will act, not just in the best interests of shareholders but in the interests of all stakeholders, including its employees. When employees have a high level of trust in their firm, they are likely to be more productive (Nyhan & Marlowe, 1997), engage in more critical decisions (Korsgaard et al., 1995), be less corrupt (Uslaner, 2004), and support the corporate strategy (Korsgaard et al., 1995). They may even relinquish many of their own concerns, believing the firm has their best interests at heart (Uslaner, 2004). Because of its pervasiveness within corporate culture, trust sheds light on how people respond to managerial structures and decisions (Wang & Hsieh, 2013). It helps shape the confidence people have in the organization and its progress towards its long-term goals.

The perception of women as leaders impacts that organization on several performance dimensions. Larger firms that employ high percentages of women in management positions, and whose associates have a strong positive perception on their abilities, have high return on equity, return on assets, return on sales, and return on investments (Shrader et al., 1997). Among large, public Australian firms, strong social performance was the positive link that mediated between women on boards and financial performance (Galbreath, 2018). Firms that support equitable policies and practices, such as those that actively support women as leaders, may see strong strategic benefits alongside benefits of strong organizational trust (Joshi & Diekman, 2022).

Indeed, women in leadership positions are often associated with stronger perceived firm performance (Katzenbach et al., 1995; Krishnan & Park, 2005), suggesting that a positive perception of women's ability to lead is associated with a positive overall perception of the firm. For example, in their study of US firms from 1992-2004, Khan & Vieito (2013) found that firms with women chief executive officers (CEOs) showed performance improvements compared to firms with male CEOs, and the firm's risk level was considered to be lower when women held a key leadership role. Thus, the perception of women as managers will influence employees' perception of the firm's performance. Based on the preceding, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1: The greater the organizational trust, the more positive the perception of organizational performance.

Hypothesis 2: The more positive the perception of women as managers, the more positive the perception of organizational performance.

Organizational trust influences employees' perception of women and their perceived performance in leadership roles (Javalgi et al., 2011). It encourages employees to accept decisions of top management (Uslaner, 2004) and to be a part of implementing such decisions. In this case, characteristics of the trustee is tightly coupled with their trustworthiness, such that the level of trust a person has in someone is transferred to the entity associated with that individual. In other words, people who trust organizations will also have greater trust in a specific organization (Pirson, et al., 2019). Higher organizational trust will drive employees to favor and embrace the firm's managerial decisions, including those decisions to engage more women as managers, and the decisions of those women managers.

Trust in leadership is associated with positive organizational performance, work attitudes and organizational citizenship behaviors (Dirks & Ferrin, 2002). Likewise, employees' perceptions of the firm's other behaviors, such as corporate social responsibility, positively influence their perceptions of the firm's performance (Young & Makhija, 2014).

Trust usually occurs because of the belief that the trustworthy party embodies attributes such as competence, concern, openness, and reliability (Mishra, 1996). When employees have high levels of trust in the people in their organizations, personified by ability, benevolence, and integrity (Mayer et al., 1995; Mayer & Davis, 1999), that trust will extend to other aspects of the organization (Tan & Lim, 2009), including how leaders are identified and whether women are included in that process. Thus, if trust increases the confidence one has in another party (Schoorman et al., 2007), we suggest that the employees' perceptions of women as managers will influence the relationship between organizational trust in the firm and how employees view its performance.

So, if employees trust their firm, they will trust managerial strategies and decisions. The more that employees trust their firm, the more positive their perceptions of women leaders in their organization will be. Similarly, if employees perceive women in leadership as positive, the relationship between organizational trust and organizational performance will be more positive. Because of this, we posit the following relationship:

Hypothesis 3: The perception of women as managers mediates the relationship between organizational trust and organizational performance.

Men and women behave differently in organizations (Sánchez & Lehnert, 2019) and an employee's gender may influence the relationship between organizational trust, their perception of women as managers, and organizational performance (Correll, 2017). Men and women perceive each other differently especially as they serve in leadership roles (Prime et al., 2009). For example, a study about leadership styles found that women transformational leaders were less favored and more often criticized by male subordinates, compared to women subordinates (Ayman et al., 2009).

Men are often reluctant to work for a woman manager, whereas women who identify with being a woman in a managerial role, may be more empathetic and understanding (Berkery et al., 2013). Men tend to gendertype managerial roles with a preference towards other males, while women classify managerial roles as being for both men and women (Britton 2017). A study of women leaders in academia found that values typically attributed to women (e.g., multi-tasking, supporting and nurturing, people and communication skills, and teamwork), frequently conflict with universities' norms and cultures (Joyner & Preston, 1998; Priola, 2004) that tend to value a more masculine culture. In settings where women are more likely to see themselves in a leadership role, they will not see much distinction between themselves and other women as managers (Sánchez & Lehnert, 2019). Men may perceive women leaders as an anomaly, as something different, unique, and outside of their ordinary experience. Women, on the other hand, are experienced leaders de facto and often operate without the title and recognition, therefore, they often perceive women leaders as just leaders. This difference between the way men and women perceive women leaders will influence the relationship between trust and the perception of the latter as managers, as posited below:

Hypothesis 4: Gender moderates the relationship between organizational trust and the perception of women as managers, since men see women as managers as different, while women do not.

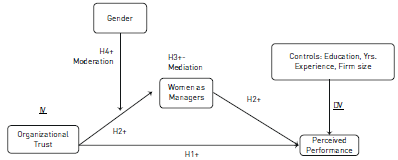

Figure 1 highlights our theoretical model. It proposes that trust is important to understanding the relationship between an employee and how they perceive women as leaders in their organization. This component of trust drives an understanding of the organizational culture. Further, gender plays an important role in this association, moderating the relationship between trust and women as leaders, because men and women perceive women leaders differently. This provides a stronger understanding of how employees perceive their organization and its performance.

3. Methodology

To test our hypotheses, we administered surveys to managerial level, working professionals enrolled in graduate and executive education studies at universities in two Latin American countries (Mexico and Peru) and the United States of America. The sample included owners, CEOs, presidents, general managers, directors, managers, and supervisors of public and non-publicly traded organizations, reflecting a diverse population of active and engaged businesspeople.

As emphasized by Aguinis et al. (2020), research in Latin America is crucial to developing and testing theories with consequences for important societal issues (Hincapie, & Sánchez, 2022). We selected Mexico and Peru given these two Latin American nations are good examples of emerging markets that have undergone significant reforms. These reforms were designed to address social and economic challenges, including gender equity (EIU, 2013a, 2013b) in order to make their countries more stable and economically sound (Ciravegna et al, 2016).

In addition to these emerging markets, we wanted to examine the results in a developed nation that has also implemented and addressed gender equity throughout the workplace over the past several decades (Inglehart & Norris, 2003), and thus we chose the United States. Adding the sample from the United States offers a distinctive contrast to that of a Latin American country.

These diverse sample population presents a wide array of viewpoints regarding the perceptions of the firm's social structure and trust in the firm. Further, the use of diverse populations as a replication allows us to potentially mitigate possible social or cultural biases.

Native Spanish speakers translated and back translated the survey. The Latin American survey received 548 responses; however, due to incomplete data, 321 were usable. The average age of the Latin American sample was 38, with 43% women and 57% men. We controlled for education, with 14% of the respondents having an undergraduate degree and 86% holding a Post Baccalaureate degree. We measured firm size by the number of employees, with the average size being 4,580. Over 98% of the respondents were employed, with the other two percent having been recently employed. Respondent's position also represented a cross section of the firm, with 49% as upper-level managers, 13% as Owners/CEOs, and 36% as mid-level employees or supervisors.

To address potential common methods variance concerns (Podsakoff et al., 2003) we followed the process identified by Steenkamp and Baumgartner (1988) and verified cross- cultural invariance in combining the Latin American samples. Cross-cultural invariance was achieved by constraining no less than two items between the two samples. This produced a non-significant comparison between nested models (Chi-Square Difference = 20.72, df = 13; p > .05), allowing us to combine the samples. The final constrained nested model still shows adequate fit (RMSEA = .05; CFI = .90). Table 1 highlights the descriptive statistics and correlations for the Latin American sample.

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations - Latin American Sample

| Mean | s.d. | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Education | 0.87 | 0.33 | 1 | .08 | .04 | -.08 | -.11 | -.10 | -.06 | |

| 2. Work Experience | 15.23 | 9.26 | 1 | -.05 | -.24** | -.08 | .09 | .05 | ||

| 3. Firm Size | 4580.83 | 28131.05 | 1 | -.02 | .06 | .07 | 11* | |||

| 4. Gender | .41 | 0.49 | 1 | .47** | -.04 | .03 | ||||

| 5. Women as Managers | 6.12 | .92 | .87 | 1 | 12* | 15* | ||||

| 6. Organizational Trust | 5.05 | 1.26 | .86 | 1 | 58** | |||||

| 7. Organizational Performance | 5.21 | 1.40 | .90 | 1 |

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

*. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Source: own elaboration.

The USA survey received 94 responses, of which only 72 were usable due to missing data. The average age was 33, with 38% women and 62% men; 15% of the respondents have an undergraduate degree and 85% hold a post-bachelor's degree. Over 99% of the respondents were employed. Position within the firm represented 50% as upper-level managers, 6% as Owners/CEOs, and 42% as mid-level employees or supervisors. The average firm size, by number of employees, was 24,870. Table 2 highlights the descriptive statistics and correlations for the USA sample.

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations - USA Sample

| Mean | s.d. | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Education | .85 | 0.36 | 1 | .09 | .01 | -.28* | -.34** | -.23* | -.18 | |

| 2. Work Experience | 12.85 | 11.00 | 1 | -.08 | -.03 | .37** | .30* | .18 | ||

| 3. Firm Size | 25189.20 | 73163.30 | 1 | .11 | -.03 | .00 | -.11 | |||

| 4. Gender | 0.32 | 0.47 | 1 | .23* | .24* | .11 | ||||

| 5. Women as Managers | 4.39 | 2.65 | .95 | 1 | .65** | .58** | ||||

| 6. Organizational Trust | 4.28 | 1.66 | .69 | 1 | .60** | |||||

| 7. Organizational Performance | 4.46 | 1.48 | .79 | 1 |

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

*. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Source: own elaboration.

3.1 Variables, Scale Development, and Reliability

Respondents answered 53 questions comprising eight subscales, using a seven-point Likert scale. The principal constructs were organizational trust, perception of women as managers, and perception of organizational performance.

To measure organizational trust, we adopted questions from Huff and Kelly (2005) and Sánchez and Lehnert (2019). Exemplar questions measuring trust include: "There is a very high level of trust throughout my firm," and "I am willing to depend on my firm to back me up in difficult situations."

Perceptions of women as managers was measured using Terborg et al.'s (1977) women as managers (WAMS) scale. WAMS has been used extensively in management literature to understand how men and women perceive women in management and leadership (Baldner and Pierro, 2024) and includes 21 items such as statements related to intention, ability, responsibility, and aggressiveness. These items highlight the stereotypes that women may face in managerial positions with higher rating reflecting a more negative position towards women as leaders (Contu, et al, 2023). The validity and reliability of WAMS was established during the initial development (Terborg et al., 1977) and has continued to show strong reliability over the last four decades (e.g., Javalgi et al., 2011; Baldner and Pierro, 2024; and Contu et al. 2023).

Organizational performance was measured by asking respondents if they perceived their firm was much better than competitors in terms of revenue growth, net income growth, and overall performance (c.f., Sánchez & Lehnert, 2018). We averaged these measures to determine perceptions of firm performance. Delaney and Huselid (1996) noted that perceptions of organizational performance are valid and appropriate measures, especially to assure respondents of confidentiality protection, since our study surveyed people working for firms in Latin America and the United States, and many of those were private or family-held.

Further, previous research in management has measured respondents' perceptions of firm performance, which tends to be positively correlated with objective measures of financial performance such as return on assets and growth in sales (Chadwick et al, 2015), making perceptions a valuable way to measure performance (Harel & Tzafrir, 1999).

We verified our constructs and ran tests of convergent and discriminant validity for all scales utilizing Fornell and Larcker's (1981) average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability measures as an alternate measure of reliability than Cronbach's alpha. Convergent validity of all items loading on each construct was above recommended levels for scalar reliability (0.6; Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Tables 1 and 2 present the AVEs and the results of these tests confirm both discriminant and convergent validity of the scale measures, and reliability within each measure for both the Latin America and USA samples.

To test for common methods variance, (Chang et al., 2010), we performed both the Harman one factor test and constrained the measurement models as recommended by Podsakoff et al. (2003). Both tests indicated that our Latin sample did not exhibit any common methods variance. The US sample single factor exhibited 53% total variance, indicating a potential for common method variance.

To follow up on the level of common method variance (Fuller et al., 2016), we employed Lindell and Whitney's (2001) partial correlational analysis. We used marker variables (economic climate and financial weakness) with no theoretical correlations to the other variables to parse out common methods bias (Lindell & Whitney, 2001). These measures were adopted by Venard (2009). Sample questions for economic climate included "Inflation is problematic for the operation and growth of firms like mine." and for financial weakness were "High interest rates are problematic for the operation and growth of firms like mine." After running the zero-ordered correlations and partial correlations on our constructs and response with a marker variable for both the Latin and the USA models, we conclude that the model is not influenced by common method bias, with no significant differences between correlations. Furthermore, these results support the validity of the models.

4. Results

We used the PROCESS macro (Hayes & Scharkow, 2013) to conduct tests of our hypotheses. Analysis on the variance of inflations (VIF) indicate that multicollinearity is not an issue, as all non-interactive term values are below 5 as recommended by Neter et al. (1996).

Table 3 tests the hypothesis relating to trust and the perception of women as managers. For each model, we controlled for Education, Work Experience, and Firm Size.

Model 1 reveals the positive effects of organizational trust and gender on the perception of women as managers (), where the stronger the trust an individual has in their firm, the more likely they are to have a positive perception of women as managers. Model 2 highlights the relationship between our variables upon organizational performance and tests the mediating effect of women as managers. In support of Hypothesis 1, we see that the stronger the organization trust, the stronger the perceived performance (). The latter also provides partial support for hypothesis 2 (), which investigates the direct effect of the perception of women as managers positively impacting the perception of firm performance.

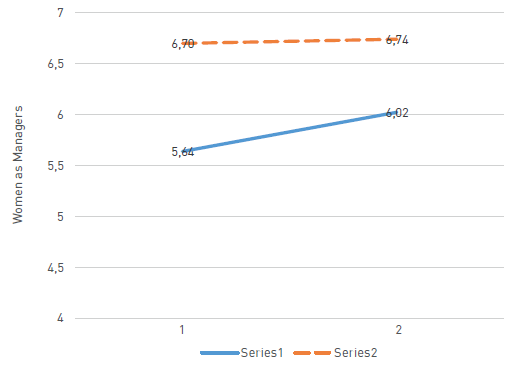

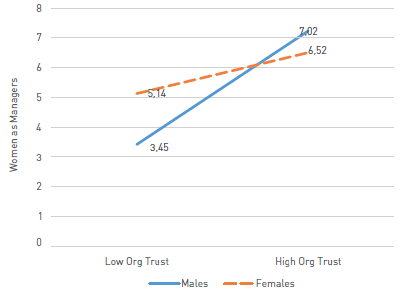

As a test of hypothesis 4, we see that there is an interactive effect of gender on the relationship between organizational trust and women as managers (). By graphing this interaction (Figures 2 and 3), we can interpret the negative coefficient within this relationship. The graph highlights that gender moderates the relationship between trust and women as managers for men, but not for women. This is an interesting result as it implies that the relationship between trust and women as managers is not enhanced in the case of women respondents. For women, their perception of women managers is independent of their perception of firm performance. The two are distinctly separate concepts, whereas men's perception of women as managers is linked to their perceptions of firm performance.

Hayes' PROCESS Macro (Hayes, 2017) extends the Baron and Kenny (1986) mediation analysis method by using a bootstrap technique and produces a confidence interval for the mediation paths; those paths that exclude zero provide support for the mediating effect of women as managers. This method allows us to look at the relationship of all our variables.

Results indicate evidence for mediation at one level of the moderator (gender), but not at the other. This allows us to investigate if this mediation effect is different based upon the gender of the respondents, providing comprehensive tests of the mediation proposed in Hypothesis 3 (Preacher et al., 2007).

Mediation results indicate that there is an effect for the US sample, supporting Hypothesis 3. Specifically, the relationship between women as managers and women as respondents is insignificant, indicating no mediating effect between trust and organizational performance for women, but there is such an effect for men.

The relationship between organizational trust and performance is mediated by the perception of women as managers, such that when men have a lower perception of women as managers, this has a negative mediating effect upon their perception of firm performance. Thus, for the US sample we see that for men who have a higher perception of women as managers, there is a stronger relationship between the level of trust they have in their organization and their perception of performance. This more positive perception of women as managers spills over, such that the relationship between the trust they have in their organization positively affects their confidence in the firm's performance. This suggest that at higher levels of perceptions of women as managers by men, the relationship between trust and performance becomes a direct relationship. For women, there is a direct relationship between trust and perceived performance, and there is no relationship between the perception of women as managers and performance.

Perhaps women do not see the importance of managerial gender, because it reflects their own identity within the trust performance relationship. This mediating effect is not replicated in the Latin American sample, though the moderating effect of gender is present. We discuss this result further below.

Table 3 Organizational Trust, Gender, and Ability/Acceptability

** P<0.01, * P<0.05, † P<0.08; Numbers in parenthesis represent standard error

Source: own elaboration.

5. Discussion and Implications

Increasing gender diversity in today's organizational leadership continues to be an important goal. Our finding that employees' gender moderates the relationship between women as managers and the trust - performance relationship (Hypothesis 4) is one of the more important results of this study. Women's perception of women as managers, i.e., those who are just like me, neither strengthens nor weakens the relationship between trust and performance. This may be because women are unlikely to see a significant distinction between the abilities of their men and women managers, based on gender. Women already identify with, and have confidence, in their own capabilities as women. Therefore, women may not differentiate between the managerial abilities they see in women, as compared to those they see in men.

This finding contributes to the body of literature that examines gender, leadership, trust, and organizational outcomes. The idea that men perceive differences in men's and women's managerial abilities may help explain how these differences interact with their level of organizational trust to affect other key organizational outcomes, including performance, citizenship behaviors, and commitment (Goodwin et al., 2011). Given the current importance of current social movements, our finding directly reflects the theoretical challenges facing gender research and contributes to a better understanding of how different genders perceive women's ability to lead in the workplace.

Indeed, the moderated mediation of gender on the perception of women as managers is found only for men, and not for women (H4). This finding is important because it has implications for both theory and practice. Female leaders have been found to have an advantage over their male counterparts when it comes to leadership behaviors, employing more effective leadership actions and less ineffective leadership behaviors. However, these differences do not always lead to a female advantage in leadership effectiveness. Evidence suggests that this could be due to perceptual biases towards women (Shen & Joseph, 2021) as we also found in our current study. Further, women are significantly less likely to self-select into leadership positions when there is a possibility they will receive backlash, which is more common than their male counterparts (Chakraborty & Serra, 2023). However, we find that women-led business, even in developing nations, are actually associated with growth, opportunity, and high impact (Huamán, Guede, Cancino, & Cordova, 2022). This also offers a unique opportunity for further investigation, as it is notable that men's and women's perceptions differ here, as they do on several workplace issues such as their approaches to problem solving (Schminke & Ambrose, 1997), decision making (Correll, 2017), and ethics (Lehnert et al., 2015).

Future research and practicing managers must consider not only how to include women in higher levels of organizational leadership, but how to address the impact of men's perceptions of women leaders in the organization. Understanding how differently men perceive women, compared with how women perceive women, is key to achieving the levels of trust, confidence, and support for the organization's strategic initiatives.

The role of organizational trust (Hypothesis 1) was also supported and has theoretical importance. Organizational trust was a strong positive influence on the perception of women as managers. We noted that trust is the "preparedness to be vulnerable" (Bevelander & Page, 2011). Employees know they have little control over many strategic decisions, but when they trust their organizations, they place confidence in those decisions. High trust in the organization may significantly influence how employees view their superiors and those strategic decisions. Despite slow progress to elevate sufficient numbers of women into leadership positions, more organizations are working to name more women as leaders. Indeed, trust is particularly crucial when considering those people who are members of underrepresented groups, like women (Joshi & Diekman, 2021). Future research should examine how organizational trust, manifested in various ways, can affect perceptions of diversity in leadership. Trust may offer a powerful avenue for gaining a deeper understanding of acceptance of women in leadership roles and helping firms overcome implicit biases between genders.

It is notable that the effect of women as managers on the perception of organizational performance (Hypothesis 2), and the mediating effect of women as managers (Hypothesis 3), was not found among Latin American respondents. This may suggest that when there is a moderately positive perception of women as managers (the mean for the Latin American sample was 6.02), employees do not perceive that leadership gender influences the organizational trust-performance relationship. Are people in Mexico and Peru more accepting of women in powerful positions, and do they have less doubt about their abilities? Several Latin American countries, including Argentina, Chile, and Brazil, have a history of electing women presidents, suggesting that the ability of women to lead is seen more positively in those countries than in the United States, which has yet to elect a woman president. In other words, when people perceive that women are capable of being leaders such that they elect them as legitimate leaders, the question of gender distinction in leadership abilities becomes less relevant. People perceive their managers and leaders to be just that - managers and leaders - and they align themselves with the vision of robust equality in their organizations and societies.

5.1 Managerial relevance

Our results have several implications for managerial practice. There is an opportunity for a novel approach to improving representation of women in leadership by working to shift men's perceptions (Liu & Wilson, 2001) toward greater acceptance of and confidence in women's abilities, as may be the case in the Latin American countries. Women as leaders are associated with higher organizational earnings (e.g., Krishnan & Parsons, 2008), and improved performance and growth (Dwyer et al. 2003). As firms elevate more women to leadership, those firms experience positive financial results and additional associated effects, including more emphasis on work-life balance (see Adame, Caplliure, & Miquel, 2016).

Positive perceptions by both men and women of women's abilities to lead may be crucial to achieving organizational success because they influence other factors that result in a more trustworthy, and more successful, organization (Joshi & Diekman, 2022). Men who view women leaders favorably allow the trust they have in their organizations to positively impact their confidence in the firm's performance. Trust is the key to making this happen. Indeed, organizational trust is important to organizational success because working with others, including women colleagues and leaders, requires significant interdependence, respect, and trust one another to reach organizational goals (Joshi & Diekman, 2022). By facilitating organizational trust, it may be possible to overcome gender barriers to having women as managers. Firms that want to build organizational trust might try designing recruitment materials that boast substantial gender and other types of diversity, as suggested by Kroeper, Williams, & Murphy (2022).

Building trust in the firm's selection of leaders is a crucial step in reducing the gender disparity between employees (Correll, 2017). Wise company executives are aware of this. Organizational performance stands to benefit in firms where employees recognize the capabilities of its leaders, regardless of whether they are men or women (Javalgi et al., 2011), and where competence, integrity, benevolence, and other characteristics of trust are embedded in employees' perception of the firm (Dirks, 2000).

5.2 Limitations and future research

One of our study's limitations is the binary concept of gender. The masculine and feminine distinction of gender is necessarily limiting, especially as the cultural discussion on gender becomes broader and more inclusive in its understanding of gender-based identity. Future research might extend this study to a broader construct of gender identity and its impact on leadership.

A second limitation is based on the use of common methods. As we know, common methods variance may cause correlations to be either falsely inflated or deflated (Williams & Brown, 1994). A conversation in the literature continues, however, as to what level common methods variance needs to rise to start creating concerns of biases (see Brannick et al., 2010). We recognized this concern from our construct creation and sample selection and attempted to mitigate the biases by conducting convergent and discriminant validity testing across sample populations, using multiple sample populations within different countries, and using marker variables to test for bias (Conway & Lance, 2010).

A third and final limitation is the use of a sample from emerging market countries, and the caution required before generalizing the results to people and firms elsewhere. We recognized this concern and replicated the study using a USA sample. Nevertheless, as noted in the discussion about the lack of gender moderation in the Latin American sample, there may be cultural and institutional variables that also influence the trust, women as managers, and performance relationships in organizations in other countries.

5.3 Conclusion

There is need and opportunity to expand gender diversity among the leadership ranks in today's organizations (Abdallah & Jibai, 2020). As organizations struggle with overcoming the barriers that hinder leadership diversity, our research suggests that building greater trust might help break them down. Many leaders are committed to establishing greater organizational trust, and it may be useful for them to consider that perceptions men and women have about women leaders may differ. Those different perceptions might make their organizations vulnerable, so, to avoid vulnerability, they might work to build more diverse, open, and trustworthy organizations. Since both men and women have the ability and the desire to lead (Sánchez & Lehnert, 2019), and since men and women often lead differently, leaders of many firms might benefit from understanding how greater organizational trust by employees can drive strategic goals.

The differences in the ways men and women lead are important, and they are poised to positively impact the trajectories of modern organizations. The pace of change in firms is fast and furious, and to keep up with it, more women must serve in top leadership positions despite their current underrepresentation in the higher ranks.

Women still rise to organizational leadership at a very slow rate, and unless strategies and tactics to increase their numbers change radically, leadership diversity will not keep up. Furthermore, "women must be encouraged from the ground up to pursue opportunities, to seek supportive working relationships and to celebrate the accomplishments of other women" (Gillard & Okonjo-Iweala, 2022).

We suggest that a key strategy to do this is to build trust among employees, particularly male employees, as firms adopt strategies to promote and appoint more capable and willing women to leadership positions. This trust building, we argue, will help break down barriers that may have led some employees, particularly men, to perceive that women may not be as qualified or as capable as men to lead. In other words, building trust and expanding leadership diversity to include more women are strategies that, if implemented in tandem, will reinforce one another and create a platform for positive organizational performance. Mellody Hobson, president of Ariel Investments, challenged her colleagues at a meeting of Fortune 500 leaders who said they were "working on" more leadership diversity. Her point was blunt: "You do not 'work on' better earnings...you either do, or you do not" (Heimer, 2017), and she called for more women in powerful positions, period. Doing so is likely connected to greater perceptions of firm performance, and trust helps drive this relationship. This connection between greater gender equality in leadership and organizational trust can motivate organizational leaders to stop "working on" diversity, and to start delivering a more representative and equitable workplace that fosters trust among all individuals, thereby positioning the firm for stronger, more positive performance.